Abstract

UV-induced pyrimidine dimers block the progression of both DNA and RNA polymerases. In order to reduce the disruptive effect of these lesions on gene expression, bacteria, yeasts, and animals preferentially repair the transcribed strand of actively expressed genes, essentially employing the stalled polymerase as a detector for bulky lesions. It has been assumed, but not demonstrated, that this prioritization of repair also occurs in plants. Here we demonstrate that in the constitutively expressed gene encoding the RNA polymerase II large subunit cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are removed from the transcribed strand more rapidly than from the non-transcribed strand.

Keywords: transcription-coupled repair, UV repair, pyrimidine dimers, nucleotide excision repair

Introduction

RNA polymerases, like most DNA polymerases, stall at many DNA damage products. This stalling disrupts transcription of the gene until repair can be effected. By sequestering the transcriptional apparatus, DNA damage can also shut down transcription of undamaged genes. For this reason, the repair of transcriptionally active DNA or at least of the transcribed strand-would be expected to be a priority for the cell. Transcription-coupled repair (TCR) was first discovered by Hanawalt and coworkers (Bohr et al., 1985; Mellon et al., 1987). Working with the DHFR gene in mammalian cells, they found that pyrimidine dimers in transcriptionally active DNA were repaired more rapidly than those in neighboring non-transcribed sequences, and that this enhanced repair was entirely due to the elevated rate of repair of the transcribed strand. They proposed a general model that still stands today (Sarasin and Stary, 2007): that the presence of a stalled polymerase facilitates the recruitment of nucleotide excision repair (NER) components. This observation has since been extended to include not only NER of other UV-damaged RNA pol II-transcribed genes, but also NER of Pol I-transcribed genes (Conconi et al., 2002; Iben et al., 2002; Meier et al., 2002), and the repair of oxidative damage (Le Page et al., 2000; Sunesen et al., 2002; de Waard et al., 2003).

Transcription-coupled repair has been shown to exist in a variety of mammals and in yeast (Lommel et al., 2000). The adaptive significance of this prioritization of repair is illustrated by the presence of an evolutionarily unrelated mechanism in bacteria (Selby and Sancar, 1993). The presence of TCR in bacteria and yeast, with their relatively compact transcriptional units, also indicates that TCR did not evolve simply to help cope with the higher frequency of lesions/gene in mammals, whose genes often include very large introns. However, although TCR is often regarded as a ubiquitous repair mechanism, its presence or absence has not yet been determined in plants. In this short report we demonstrate that, not unexpectedly, NER of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers is enhanced in the transcribed strand of the nuclear housekeeping gene encoding the RNA polymerase II large subunit in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Landsbergerecta (Ler) was grown on nutritive agar (Kranz and Kirchheim, 1987) as previously described (Fidantsef et al., 2000). Seeds were sown at a density of approximately 1,000 seeds (12.5 mg)/100 mm2 plate and then kept at 4°C for 2 days. The plates were then brought to the growth chamber (20°, 16 h day) where they were grown under cool white lamps. The plates were placed in a vertical position to prevent the root tips from growing into the (UV-absorbing) agar.

UV-B irradiation

Five-day-old seedlings were then irradiated with UV-B for a final dose of 0–6 kJ m−2 using a UV-transilluminator (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) filtered with 0.005 ml cellulose acetate, with a flux rate of 3.53 mW cm−2 as measured with a UV-B-specific probe (UVP, Inc., San Gabriel, CA, USA). The tops were removed from the plates prior to irradiation. UV-irradiation and harvesting of seedlings was conducted under dim red light (Photolamp 6W, C.P.M., Dallas, TX, USA). We attempt to harvest about 1 g of seedlings for each treatment and/or time point, which was in general obtained by pooling seedlings from three plates. Seedlings from control (unirradiated) plates were harvested at the time of irradiation and frozen in liquid Nitrogen for later DNA extraction. The remaining plates were irradiated and seedlings were either immediately harvested and frozen or kept in the dark for 24 h and then harvested and frozen.

DNA extraction, digestion, electrophoresis, blotting, and hybridization

DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Maxi Kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). DNA concentration was measured using a DyNA Quanti 200 Fluoremeter (Hoefer Pharmacia, San Francisco, CA, USA) and digested with BstEII (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA) in the presence of 5 mM spermidine. Digested DNA was then aliquoted into two equal volumes. To each aliquot NET buffer was added to a final concentration of 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 100 μg/ml of BSA. T4 endonuclease V (generously provided by R. S. Lloyd) was prepared to a concentration of 1.4 μg/ml in 25 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 6.8), 100 μg/ml BSA. To induce nicking at CPDs, 1 μl of this stock solution was added per μg of DNA and the DNA incubated at 37°C for 30 min. To the aliquot not digested with T4 endo V, the T4 endo V dilution buffer was added as a mock digest. The reaction was stopped by adding 1× loading dye to each sample as described (Friedberg and Hanawalt, 1981). Samples (at least 1 μg of DNA/lane) were electrophoresed on a 0.5% alkaline gel (9.5 cm) in 1 mM EDTA and 30 mM NaOH at 22 V for around 16 h. Southern blotting, hybridization and washes were performed as described (Spivak and Hanawalt Philip, 1995) with the exception that Hybond-N+ or Hybond-XL nylon membranes (Amersham Pharmacia, UK) were used. Membranes were exposed to a Phosphor Screen (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Quantitation of band intensity

Phosphor Screens were scanned in the Storm 860 (Molecular Dynamics) for the quantitation of bands via ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Quantitation of CPDs was performed as previously described (Chen et al., 1996).

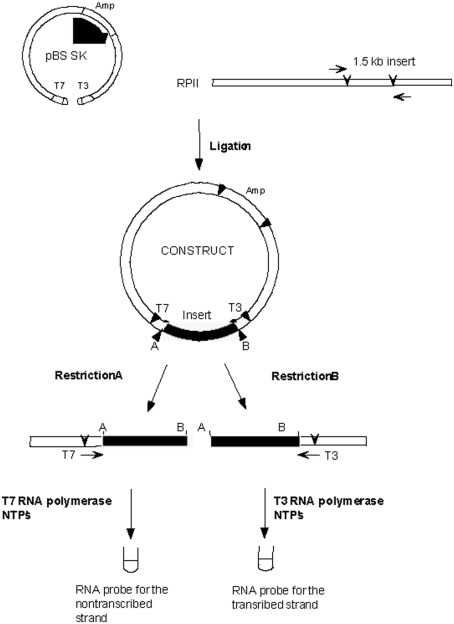

Probes

A 1.5-kb fragment of the A. thaliana RPII gene for RNA polymerase large subunit (At4g35800; Nawrath et al., 1990) was used as a probe. The 1.5-kb PCR fragment was obtained using genomic DNA from Arabidopsis ecotype Ler as a template and the following primers: 5′-GGTTTGATGAGGAGGGAGGC-3′ (upper primer) and 111 5′-GATGTGGGTGAGTATGATGGAG-3′ (lower primer) which amplified the gene from positions 5990 to 7496. This fragment was subcloned into pBluescript SK+ vector between the BamHI and PstI sites. This vector contains the T3 and T7 RNA polymerase promoters positioned in opposite orientations flanking the multiple cloning site of the vector. Digestion of this construct with EcoRI or XbaI restriction enzymes linearizes the plasmid. The linear vectors produced by digestion with each of these restriction enzymes were separately gel purified. A radiolabeled specific-strand probe that detects the transcribed DNA strand (TS probe) was produced by using the EcoRI linearized vector with the T3 RNA polymerase using the Riboprobe in vitro Transcription Systems (Promega) following manufacturer’s instructions. Similarly, a specific-strand probe that detects the non-transcribed DNA strand (NTS probe) was produced and 32P labeled by using the XbaI linearized vector with the T7 RNA polymerase (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Generation of the single-strand probe for RPII. T3 and T7 RNA Polymerase promoters flank the multiple cloning site (MCS) of the pBS SK+ vector. The direction of transcription of each RNA polymerase is shown in the dotted arrows. Digestion of pBS SK+ with BamHI and PstI linearizes the vector, producing sites for cloning of the 1.5-kb A. thaliana RPII insert. The arrow in the insert indicates the direction of transcription of the gene. The 1.5-kb A. thaliana RPII insert lies between the T3 and T7 RNA Polymerase promoters of pBS SK+. Digestion of the vector with EcoRI linearizes the vector such that the T3 RNA Polymerase makes a transcript complementary to the transcribed strand of the RPII gene. Digestion of the vector with Xba I linearizes the vector so that the T7 RNA Polymerase makes a transcript complimentary to the non-transcribed strand of the RPII gene. Addition of RNA synthesis reaction components (appropriate RNA Polymerase and radiolabeled NTPs) produces the probes for detection of each of the DNA strands of the RPII insert.

Results and Discussion

The Southern blot (aka Bohr, or strand-specific) assay for strand-specific repair relies on the quantitation of dimer-free DNA present in a specific restriction fragment population. In order to accurately measure repair an initial average of at least one dimer/fragment must be generated, and this restriction fragment must lie within a transcribed region. Plants generally have relatively small introns, and so small transcribed regions. This may represent an UV-resistant adaptation, but it more likely reflects the very different process required for splice site recognition in plants vs. animals (Brown and Simpson, 1998). The RNA polymerase large subunit gene, a housekeeping gene expressed in all tissues, present a large enough (10 kb) target for the Southern blot assay. Irradiation at a UV-B dose sufficient to induce 1 CPD/10 kb is toxic but not lethal to the Arabidopsis seedling.

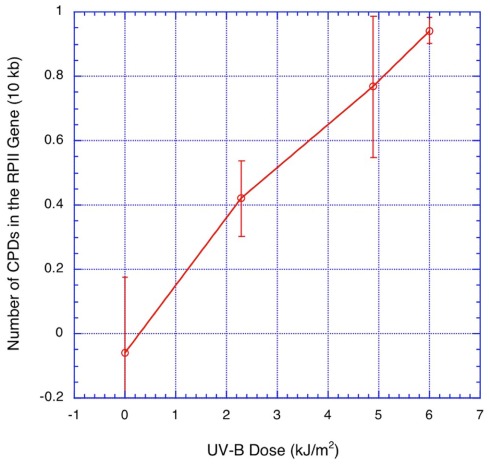

UV-B induction of dimers in the Arabidopsis seedling follows a poisson distribution

Calculation of dimer frequency as: ln(I+/I−) (intensity of the band in the +T4 endonuclease V lane/intensity in the paired “no T4endoV” lane) is based on the assumption that dimers are randomly distributed throughout the biological sample in this case, the Arabidopsis seedling. We had previously shown that this is true for seedlings using nuclear rDNA (Chen et al., 1994), employing two different methods (the alkaline Sucrose gradient and the Southern blot assay) that produced approximately same results. Here we employed the Southern blot assay on denaturing gels to demonstrate that with increasing doses of UV-B, the induction of dimers in a 10-kb fragment of genomic DNA extracted form Arabidopsis seedlings behaved linearly (Figure 2). This indicates that as previously observed UV-B induces a random distribution of dimers in Arabidopsis seedlings. This dose–response curve also allowed us to determine the dose required (6 kJ/m2 UV-B) to induce an average of approximately 1 CPD/10 kb. This value is consistent with that determined for Arabidopsis seedlings in other labs (Draper and Hays, 2000).

Figure 2.

The induction of CPDs as assayed via alkaline Southern increases linearly with UV-B dose. Five-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on 1% agarose plates were exposed to 0, 2.2, 4.8, and 6 kJ/m2 of UV-B. Seedlings were immediately harvested in liquid nitrogen after irradiation. DNA samples were digested with BstEII, and divided into two equal aliquots. One aliquot of each sample was subsequently digested with T4 endo V. The digests were run on alkaline gels, and Southern blots were probed with a double strand 32P labeled probe with a 1.5-kb double-stranded fragment of the RPII gene. Signals produced by the probe were measured via phosphorimager. The “0 UV-B” serves as a control for non-specific nuclease activities in the T4 endo V. Values are derived from a minimum of 10 paired (T4 endo+/T4endo−) lanes representing three biological repeats for each UV dose.

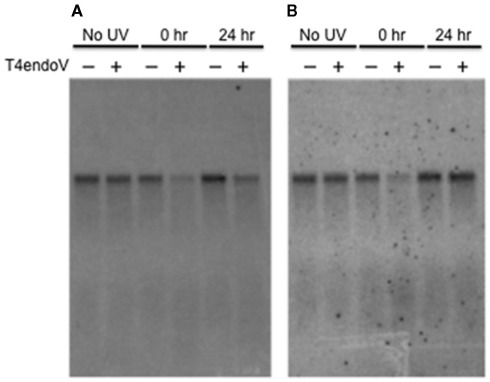

Dark repair of CPDs is enhanced on the transcribed strand

Dark repair of global CPDs in Arabidopsis seedlings is very slow in Landsberg erecta it is negligible over a 24-h period (Britt et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1996; Tanaka et al., 2002). In order to determine whether CPDs were more efficiently repaired in the transcribed strands of genes, we measured the frequency of CPDs remaining in the transcribed vs. non-transcribed strands of a 10-kb transcribed fragment of the RNA polymerase large subunit gene. CPD content was measured in seedlings immediately after irradiation and after 24 h. The DNA was restriction digested with BstEII, divided in equal aliquots, one aliquot was treated with T4 endonuclease V, and the resulting preparations loaded onto a denaturing gel. The Southern blot was first hybridized with a probe for the non-transcribed strand of DNA (Figure 3A), the probe was then stripped from the blot, and the blot rehybridized with a probe for the transcribed strand (Figure 3B). Figure 3 shows one representative blot. We measured the signals produced from three independent DNA samples (“biological replicates”). The majority of samples were loaded repeatedly onto the blot, to reduce effects of pipetting error. The CPD values presented in Table 1 represent the average of the values derived for each of the independent samples.

Figure 3.

The repair of CPDs in Arabidopsis seedlings. Five-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on 1% agarose plates were exposed to 0 or 6 kJ/m2 UV-B. Seedlings from half of the irradiated plates were immediately harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen after irradiation (0 h). Remaining plates were stored in the absence of light and seedlings were harvested 24 h after irradiation (24 h). Processing and analysis of the DNA was as described in Figure 2. (A) Blot was probed with RNA probe for non-transcribed strand. (B) The same blot, stripped and reprobed for the transcribed strand.

Table 1.

Preferential repair of CPDs in transcribed strand of the Arabidopsis thaliana RPII gene.

| Transcribed strand | Transcribed strand | Non-transcribed strand | Non-transcribed strand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (hours) | Dimer frequency | % Dimer removal | Dimer frequency | % Dimer removal |

| NO UV | 0.171 ± 0.052 | N/A | 0.200 ± 0.056 | N/A |

| 0 | 1.088 ± 0.093 | 0 | 1.135 ± 0.101 | 0 |

| 24 | 0.401 ± 0.174 | 63 | 0.942 ± 0.100 | 17 |

Values are derived from a minimum of 10 paired (T4 endo+/T4endo−) lanes representing three biological repeats.

The initial frequency of CPDs was similar in each strand of the irradiated samples (1.1 lesions/10 kb), indicating that both strands have similar susceptibility to DNA damage. DNA from seedlings harvested after a 24-h after UV-B irradiation, however, displayed significantly different frequencies of dimers on the transcribed vs. non-transcribed strands. We found that CPDs persisted in the non-transcribed strand (just as they do in global genomic DNA; Britt et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1994), while being removed specifically from the transcribed strand (Figure 3; Table 1). Our results indicate that the transcribed strand is preferentially repaired over the non-transcribed strand of DNA in this gene, suggesting that the process of TCR is conserved in plants.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steven Lloyd for the T4 endonuclease V enzyme, and Ki Baek for his assistance in this project. This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (grant no. 98–35301–6058).

Abbreviations

CPD, cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer; TCR, transcription-coupled repair.

References

- Bohr V. A., Smith C. A., Okumoto D. S., Hanawalt P. C. (1985). DNA repair in an active gene: removal of pyrimidine dimers from the DHFR gene of CHO cells is much more efficient than in the genome overall. Cell 40, 359–369 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90150-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt A. B., Chen J. J., Wykoff D., Mitchell D. (1993). A UV-sensitive mutant of Arabidopsis defective in the repair of pyrimidine-pyrimidinone(6-4) dimers. Science 261, 1571–1574 10.1126/science.8372351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. W., Simpson C. G. (1998). Splice site selection in plant pre-mRNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 77–95 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-J., Jiang C.-Z., Britt A. B. (1996). Little or no repair of cyclobutyl pyrimidine dimers is observed in the organellar genomes of the young Arabidopsis seedling. Plant Physiol. 111, 19–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-J., Mitchell D., Britt A. B. (1994). A light-dependent pathway for the elimination of UV-induced pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidinone photoproducts in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 6, 1311–1317 10.2307/3869828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conconi A., Bespalov V. A., Smerdon M. J. (2002). Transcription-coupled repair in RNA polymerase I-transcribed genes of yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 649–654 10.1073/pnas.022373099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waard H., de Wit J., Gorgels Theo G. M. F., van den Aardweg G., Andressoo J.-O., Vermeij M., van Steeg H., Hoeijmakers Jan H. J., van der Horst Gijsbertus T. J. (2003). Cell type-specific hypersensitivity to oxidative damage in CSB and XPA mice. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2, 13–25 10.1016/S1568-7864(02)00188-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper C. K., Hays J. B. (2000). Replication of chloroplast, mitochondrial and nuclear DNA during growth of unirradiated and UVB-irradiated Arabidopsis leaves. Plant J. 23, 255–265 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00776.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidantsef A. L., Mitchell D. L., Britt A. B. (2000). The Arabidopsis UVH1 gene is a homolog of the yeast repair endonuclease RAD1. Plant Physiol. 124, 579–586 10.1104/pp.124.2.579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg E. C., Hanawalt P. C. (eds). (1981). DNA Repair: A Laboratory Manual of Research Procedures. New York: M. Dekker [Google Scholar]

- Iben S., Tschochner H., Bier M., Hoogstraten D., Hozak P., Egly J.-M., Grummt I. (2002). TFIIH plays an essential role in RNA polymerase I transcription. Cell 109, 297–306 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00729-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranz A. R., Kirchheim B. (1987). Genetic Resources in Arabidopsis, Vol. 24 Frankfurt: Botanical Institute, J. W. Goethe-University [Google Scholar]

- Le Page F., Kwoh Ely E., Avrutskaya A., Gentil A., Leadon Steven A., Sarasin A., Cooper Priscilla K. (2000). Transcription-coupled repair of 8-oxoGuanine: requirement for XPG, TFIIH, and CSB and implications for Cockayne syndrome. Cell 101, 159–171 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80827-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommel L., Bucheli M. E., Sweder K. S. (2000). Transcription-coupled repair in yeast is independent from ubiquitylation of RNA pol II: implications for Cockayne’s syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9088–9092 10.1073/pnas.150130197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A., Livingstone-Zatchej M., Thoma F. (2002). Repair of active and silenced rDNA in yeast. The contributions of photolyase and transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 11845–11852 10.1074/jbc.M110941200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon I., Spivak G., Hanawalt P. C. (1987). Selective removal of transcription-blocking DNA damage from the transcribed strand of the mammalian DHFR gene. Cell 51, 241–249 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90151-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath C., Schell J., Koncz C. (1990). Homologous domains of the largest subunit of eukaryotic RNA polymerase Ii are conserved in plants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 223, 65–75 10.1007/BF00315798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarasin A., Stary A. (2007). New insights for understanding the transcription-coupled repair pathway. DNA Repair (Amst.) 6, 265–269 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby C. P., Sancar A. (1993). Molecular mechanism of transcription-repair coupling. Science 260, 53–58 10.1126/science.8465200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivak G., Hanawalt Philip C. (1995). Determination of damage and repair in specific DNA sequences. Methods 7, 147–161 10.1006/meth.1995.1021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunesen M., Stevnsner T., Brosh Robert M., Jr., Dianov Grigory L., Bohr Vilhelm A. (2002). Global genome repair of 8-oxoG in hamster cells requires a functional CSB gene product. Oncogene 21, 3571–3578 10.1038/sj.onc.1205443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A., Sakamoto A., Ishigaki Y., Nikaido O., Sun G., Hase Y., Shikazono N., Tano S., Watanabe H. (2002). An ultraviolet-B-resistant mutant with enhanced DNA repair in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129, 64–71 10.1104/pp.010894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]