Abstract

Assigning functions to the >30,000 proteins encoded by the Arabidopsis genome is a challenging task of the Arabidopsis Functional Genomics Network. Although genome-wide technologies like proteomics and transcriptomics have generated a wealth of information that significantly accelerated gene annotation, protein activities are poorly predicted by transcript or protein levels as protein activities are post-translationally regulated. To directly display protein activities in Arabidopsis proteomes, we developed and applied activity-based protein profiling (ABPP). ABPP is based on the use of small molecule probes that react with the catalytic residues of distinct protein classes in an activity-dependent manner. Labeled proteins are separated and detected from proteins gels and purified and identified by mass spectrometry. Using probes of six different chemotypes we have displayed activities of 76 Arabidopsis proteins. These proteins represent over 10 different protein classes that contain over 250 Arabidopsis proteins, including cysteine, serine, and metalloproteases, lipases, acyltransferases, and the proteasome. We have developed methods for identification of in vivo labeled proteins using click chemistry and for in vivo imaging with fluorescent probes. In vivo labeling has revealed additional protein activities and unexpected subcellular activities of the proteasome. Labeling of extracts displayed several differential activities, e.g., of the proteasome during immune response and methylesterases during infection. These studies illustrate the power of ABPP to display the functional proteome and testify to a successful interdisciplinary collaboration involving chemical biology, organic chemistry, and proteomics.

Keywords: papain-like Cys protease, matrix metalloprotease, serine hydrolase, proteasome, acyltransferase, esterase, lipase

In this postgenomic era, plant scientists face the daunting task of assigning functions to the more than 30,000 proteins that are encoded by the Arabidopsis genome. In efforts to accelerate this process, several genome-wide technologies have been developed, permitting the study of biomolecules collectively, rather than individually. These approaches have generated a tremendous wealth of information about genomes, transcriptomes, and proteomes of Arabidopsis, yielding insights into diverse biological processes. Yet a crucial piece of information is missing between the proteome and the processes in which proteins participate, namely: activity. The actual activity of a protein is difficult to predict from its presence since activity is predominantly regulated by various post-translational processes, such as phosphorylation, translocation, and processing. Since the activity of proteins is crucial for describing and understanding their roles in living systems, genome-wide technologies to reveal activities of numerous proteins in proteomes will be fundamental to the assignment of mechanistic and biological functions to Arabidopsis proteins.

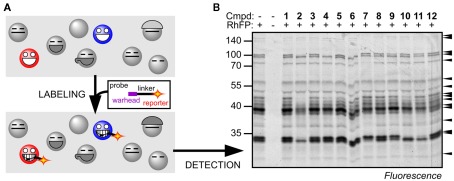

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) is a key technology in activity-based proteomics reviewed by Cravatt et al. (2008), which is based on the use of biotinylated (or otherwise labeled) small bioreactive molecules (probes) that react with active site residues of proteins in an activity-dependent manner (Figure 1A). The reaction results in a covalent, irreversible bond between the protein and the probe, which enables subsequent analysis under denaturing conditions. Labeled proteins can be detected on protein blots and the proteins can be purified and identified by mass spectrometry. This readout does not provide substrate conversion rates, but reflects which active sites are accessible, which is a hallmark for protein activities (Kobe and Kemp, 1999).

Figure 1.

Principle of ABPP. (A) Activity-based probes bind to the substrate binding site and react with the catalytic residue to lock the cleavage mechanism in the covalent intermediate state. Proteins that are not active, e.g., inhibited or not activated, cannot react with the probe. Covalent and irreversible labeling facilitates the detection and identification of the labeled proteins. (B) Example of Ser hydrolase activities displayed in Arabidopsis leaf proteomes by labeling with RhFP. Selective inhibition of different Ser hydrolases by preincubation with 12 different agrochemicals is detected by the absence of labeling of several proteins. For more information see (Kaschani et al., 2011).

Ideally, one would like to display all protein activities of a given proteome. Probes, however, have a specificity spectrum which targets them to different subsets of proteins. The advantage is that this significantly simplifies the activity proteomes, which facilitates quantitative high-throughput analysis with one-dimensional (1-D) protein gels (e.g., Figure 1B). In contrast, it also implies that in order to obtain a more complete picture of the proteome activity of Arabidopsis, individual probes for distinct protein classes will have to be validated.

Here, we will review the principle and opportunities of ABPP for functional genomics research and the contributions that we have made to introduce ABPP into Arabidopsis research. We summarize our approaches to detect activities in extracts and in living cells and summarize all Arabidopsis proteins that have been labeled with activity-based probes. For an overview on the use of ABPP approaches in plant biotechnology and in studies on plant–pathogen interactions, however, see (Kolodziejek and Van der Hoorn, 2010) and (Richau and Van der Hoorn, 2011), respectively.

Design, Specificity, and Detection of Activity-Based Probes

The design of the probe determines which class of proteins is targeted, and with what specificity. Probes consist of a warhead, a binding group, a linker, and a tag. The warhead is the reactive group that irreversibly reacts with the protein, usually at its active site. The binding group provides the probe with affinity for the target and determines the selectivity for certain sub-classes of proteins. The linker provides distance to the tag and can be cleavable. The tag facilitates detection and/or purification on the basis of radioactivity (e.g., 125I), fluorescence (e.g., rhodamine), affinity (e.g., biotin), or chemical reactivity (e.g., an alkyne or azide moiety; Sadaghiani et al., 2007).

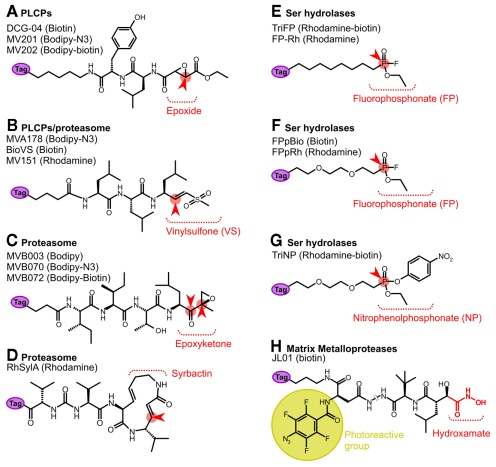

The specificity of the probe is primarily determined by the binding group and the warhead. DCG-04 (Figure 2A), for example, carries a leucine in the binding group and an epoxide warhead, and targets papain-like cysteine proteases, since these enzymes prefer a hydrophobic amino acid at the P2 position in the substrate (Greenbaum et al., 2000). Other probes target phosphatases, kinases, glycosidases, serine proteases, or the proteasome (Evans and Cravatt, 2006; Cravatt et al., 2008). These probes have been very useful in studies on activation and regulation of particular enzymes.

Figure 2.

Activity-based probes used in Arabidopsis research. These probes label papain-like Cys proteases (PLCPs, A); the proteasome (B–D); serine hydrolases (E–G); and matrix metalloproteases (H). The reactive binding moiety is depicted. The reactive group is indicated in red and the site for attack by the catalytic residue of the enzyme indicated with a red arrowhead. The metalloprotease probe JL01 is equipped with a photoreactive group (yellow). The reporter tag (purple) can be for affinity (biotin), fluorescence (Bodipy or Rhodamine), or a chemical mini tag (azide or alkyne). For more detailed information on the protease probes, see (Van der Hoorn and Kaiser, 2011).

Not only the probes but also the detection strategies have significantly evolved over the past few years. Fluorescent tags were introduced to facilitate quantitative high-throughput screening, e.g., of cancer cell lines (Patricelli et al., 2001; Jessani et al., 2002, 2004). Gel-free profiling was developed to increase the detection range by direct analysis of purified and digested labeled proteins by multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT), which increased the number of identified fluorophosphonate probes (FP) targets from 15 to 50 per proteome (Jessani et al., 2005a) and cleavable linkers were introduced to improve the release of the labeled peptide during purification and determine the labeled residue reviewed by Willems et al. (2011). New two-step labeling procedures have been introduced to generate smaller, membrane permeable probes for in vivo labeling (Speers and Cravatt, 2004; Willems et al., 2011). This two-step labeling also simplifies probe synthesis and provides a free choice of tag for the selected binding group and warhead. Finally, heavy and light cleavable reporter tags have been introduced to facilitate quantitative proteomics of labeled peptides (Weerapana et al., 2010).

ABPP as an Instrument for Functional Genomic Research

Pioneering work by the Cravatt and Bogyo groups demonstrated that ABPP is a powerful novel technology for functional genomic research since it provides functional information on proteins in at least four different ways:

Activity display provides genome-wide information concerning the activities of proteins. This is an essential complement for transcriptomic and proteomic data since it concerns a functional readout: activity. Activity description with FP-biotin revealed dozens of proteins associated with cancer cell invasiveness and tumor growth, which represent novel diagnostic markers and drug targets (Jessani et al., 2002, 2004).

Sub-classification is essential to describe functions for large protein families that contain members with redundant functions. Proteins with the same function act in a similar way on substrates and inhibitors. ABPP can display these features for each protein by screening small molecule libraries for inhibitors of activity-based labeling. Functional sub-classification can then be achieved by grouping proteins with similar inhibitory signatures, as shown for human papain-like cysteine proteases (Greenbaum et al., 2002).

Mechanistic identification is the case in which a protein with unknown mechanism is classified based on its reactivity toward a certain probe. KIAA0436, for example, has only low homology with other proteins, but its reactivity toward FP-biotin pointed at a catalytic triad that is conserved within the S09 family of serine proteases (Liu et al., 1999). Furthermore, sialyl acetyl esterases (SAE) were annotated as serine hydrolases after it was found that FP-biotin reacts with SAE at S127, a serine residue that is conserved among SEA-related proteins, and essential for SAE activity (Jessani et al., 2005b).

Functional annotation is most commonly achieved by traditional genetics. However, for many genes this approach is limited by redundancy, pleiotropic effects, and lethality. Chemical genetics is an upcoming technology that can overcome most of these problems since the dosage, specificity and time-point of interference of protein activity with small molecules can be chosen (Toth and Van der Hoorn, 2010). However, the specificity of the small molecule is not always known. ABPP is a powerful tool to assist in the selection of specific small molecule inhibitors (Kaschani and Van der Hoorn, 2007). ABPP was for example used to identify specific inhibitors for urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and KIAA1363 (Leung et al., 2003; Chiang et al., 2006; Madsen et al., 2006), and these specific inhibitors demonstrated that uPA activation is essential for tumor invasion (Madsen et al., 2006) and that KIAA1363 plays a key role in the lipid signaling by hydrolyzing 2-acetyl monoalkylglycerol (Chiang et al., 2006).

The Active Proteome of Arabidopsis

The Arabidopsis Functional Genomics Network (AFGN) aimed at the annotation of gene functions of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Within the AFGN program, we have launched new probes into plant science to display protein activities in the Arabidopsis proteome. This effort involved an intensive collaboration involving organic chemistry (for probe synthesis), proteomics (for identification of labeled proteins and labeling sites), and biochemistry (for characterization of labeling). Here, we review our work published so far. These studies give a proof-of-concept to display activities of more than 10 different protein classes containing over 250 Arabidopsis proteins (Table 1).

Table 1.

Arabidopsis protein activities detected by ABPP.

| Accession | Common name | Used material for ABPP1 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extract | In vivo | Agroinf. | |||||

| PAPAIN-LIKE CYS PROTEASES (30 GENES) | |||||||

| At1g47128 | RD21A | DCG-04 (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Richau et al., submitted) | MVA178 (Kaschani et al., 2009a) MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At5g43060 | RD21B | DCG-04 (Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At3g19390 | RD21C | DCG-04 (Richau et al., submitted) | – | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At3g19400 | RDL2 | DCG-04 (Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At1g09850 | XBCP3 | – | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | – | |||

| At4g35350 | XCP1 | – | – | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At1g20850 | XCP2 | DCG-04 (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Richau et al., submitted) | – | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At1g06260 | THI1 | DCG-04 (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Richau et al., submitted) | – | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At5g45890 | SAG12 | – | – | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At4g39090 | RD19A | – | MVA178 (Kaschani et al., 2009a) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||||||

| At2g21430 | RD19B | – | – | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At4g16190 | RD19C | – | MVA178 (Kaschani et al., 2009a) | – | |||

| MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||||||

| At5g60360 | AALP | DCG-04 (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| At3g45310 | ALP2 | DCG-04 (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Richau et al., submitted) | – | – | |||

| At1g02305 | CTB2 | DCG-04 (Richau et al., submitted) | – | – | |||

| At4g01610 | CTB3 | DCG-04 (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | MV201 (Richau et al., submitted) | |||

| T1 PROTEASOME CATALYTIC SUBUNITS (5 GENES) | |||||||

| At4g31300 | PBA1(β1) | BioVS (Gu et al., 2010) | – | – | |||

| At3g27430 | PBB1(β2) | BioVS (Gu et al., 2010) | – | – | |||

| At1g13060 | PBE1(β5) | BioVS (Gu et al., 2010) | MVA178 (Kaschani et al., 2009a) | – | |||

| MVB170 (Kolodziejek et al., 2011) | |||||||

| At3g26340 | PBE2(β5) | – | MVA178 (Kaschani et al., 2009a) | – | |||

| MVB170 (Kolodziejek et al., 2011) | |||||||

| S8 SUBTILISIN-LIKE PROTEASES (55 GENES) | |||||||

| At4g20850 | SBT6.2/TPP2 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriNP (Nickel et al., 2011) | – | – | |||

| At5g67360 | SBT1.7/ARA12 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At2g05920 | SBT1.8 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At4g21650 | SBT3.13 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At1g20160 | SBT5.2 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g14067 | SBT1.4 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| S9 PROLYL OLIGOPEPTIDASE-LIKE (POPLs, 23 GENES) | |||||||

| At1g76140 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriNP (Nickel et al., 2011) | – | – | |||

| At1g50380 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At4g14570 | AARE | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g24260 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g36210 | – | TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| S10 SER CARBOXY PEPTIDASE-LIKE (SCPLs, 51 GENES) | |||||||

| At2g22990 | SCPL8/SNG1 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | FPpRh (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | |||

| At2g22970 | SCPL11 | TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | FPRh (Kaschani et al., 2011) | |||

| At2g22980 | SCPL13 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At4g12910 | SCPL20 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At4g30610 | SCPL24/BRS1 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g02110 | SCPL25 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At2g35780 | SCPL26 | FPpBio, TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g23210 | SCPL34 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g08260 | SCPL35 | FPpBio, TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At2g33530 | SCPL46 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g45010 | SCPL48 | FPpBio, TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriNP (Nickel et al., 2011) | – | – | |||

| At3g10410 | SCPL49 | FPpBio, TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At2g27920 | SCPL51 | FPpBio, TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| PECTINACETYLESTERASE-LIKE (PAEs, 11 GENES) | |||||||

| At1g57590 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At2g46930 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g09410 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g05910 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g62060 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At4g19410 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At4g19420 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g23870 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g45280 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| GDSL LIPASE LIKE (52 GENES) | |||||||

| At1g28600 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g05180 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g48460 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At4g28780 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g14450 | – | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At1g09390 | – | TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At1g29660 | – | TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| CARBOXYESTERASE-LIKE (CXEs, 20 GENES) | |||||||

| At1g49660 | CXE5 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At2g03550 | CXE7 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriNP (Nickel et al., 2011) | – | – | |||

| At2g45600 | CXE8 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At3g48690 | CXE12 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriNP (Nickel et al., 2011) | – | TriNP (Nickel et al., 2011) | |||

| FPRh (Kaschani et al., 2011) | |||||||

| At3g48700 | CXE13 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| METHYLESTERASES (MESs, 20 GENES) | |||||||

| At2g23600 | MES2/ACL | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At2g23610 | MES3 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b), TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | FPRh (Kaschani et al., 2011) | |||

| OTHER SER HYDROLASES | |||||||

| At5g20060 | SH1 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | FPRh (Kaschani et al., 2011) | |||

| At5g65400 | FSH1 | FPpBio (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | FPRh (Kaschani et al., 2011) | |||

| At2g41530 | SFGH | TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| At5g65760 | S28 | TriFP (Kaschani et al., 2009b) | – | – | |||

| M10 MATRIX METALLOPROTEASES (5 GENES) | |||||||

| At1g70170 | At2-MMP | – | – | JL01 (Lenger et al., 2011) | |||

| At2g45040 | At4-MMP | – | – | JL01 (Lenger et al., 2011) | |||

| At1g59970 | At5-MMP | – | – | JL01 (Lenger et al., 2011) | |||

1Proteins were detected with the mentioned probes on extracts (first column), in living tissue (second column), or in extracts of N. benthamiana transiently expressing an Arabidopsis protein by agroinfiltration (third column).

Papain-Like Cys Proteases

Papain-like Cys proteases belong to family C1A and clan CA in the Merops protease database (Van der Hoorn, 2008; Rawlings et al., 2010) and carry a catalytic triad with a nucleophilic Cys residue. The Arabidopsis genome encodes for 30 papain-like Cys proteases that fall into nine subfamilies (Beers et al., 2004; Richau et al., submitted). Papain-like Cys proteases are encoded as pre-pro-proteases that enter the endomembrane system and become activated by proteolytic removal of the autoinhibitory prodomain. Only a few papain-like Cys proteases have been studied in Arabidopsis. Responsive-to-dessication-21 (RD21A) is encoded by a drought-responsive gene (Yamada et al., 2001). Arabidopsis aleurain-like protease (AALP) is used as a vacuolar marker protein (Ahmed et al., 2000). Senescence-associated gene-12 (SAG12) is used as a transcriptional marker for senescence (Otequi et al., 2005). XCP1 and XCP2 (xylem-specific Cys protease) are specifically expressed in the xylem and are required for protein degradation in the final stages of xylem formation (Avci et al., 2008). Responsive-to-dessication-19 (RD19) is involved in immunity against the vascular bacterial pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum (Bernoux et al., 2008). The PopP2 effectors of this pathogen physically interacts with RD19 and mislocalizes the protein to the nucleus. CTB2 and CTB3 are cathepsin-like proteases that play a role in senescence (McLellan et al., 2009). Thus, only a few protease knockout plants have phenotypes and none of the other 22 papain-like Cys proteases have been characterized.

Papain-like Cys proteases can be labeled with DCG-04, a biotinylated version of protease inhibitor E-64 (Greenbaum et al., 2000; Figure 2A). E-64 is selective for papain-like Cys proteases since it carries a peptide backbone with a leucine that targets the P2 substrate binding pocket of Papain-like Cys proteases, and an epoxide that traps the nucleophilic attack by the catalytic Cys residue of the protease. DCG-04 has been developed by the Bogyo lab and has been used frequently in medical science reviewed by Puri and Bogyo (2009).

Using ABPP with DCG-04, we showed for the first time that six papain-like Cys proteases are active in extracts from Arabidopsis leaves (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Table 1). An additional four papain-like Cys proteases were detected in extracts of Arabidopsis roots, flowers and cell cultures (Richau et al., submitted), and another 10 papain-like Cys proteases in senescent leaves (Pruzinska et al., in preparation). Most undetected papain-like Cys proteases are not transcriptionally expressed under the tested conditions. There are, however, some genes that are expressed transcriptionally, but not detected by ABPP. RD19A and RD19C, for example are highly expressed genes in leaves, but have not been detected by ABPP in extracts. To test if RD19A can be labeled by DCG-04, the protein was overproduced by agroinfiltration in Nicotiana benthamiana, labeled with a fluorescent/biotinylated DCG-04 (MV202), and the identity of the labeled protein confirmed by MS analysis (Richau et al., submitted). This demonstrated that RD19A can be labeled by DCG-04/MV202 and that the absence of labeling in extracts is not caused by the selectivity of the probe.

One limitation of labeling extracts is that proteins are exposed to unnatural conditions by the loss of compartmentalization. The loss of the cellular structure may affect protein activities and might explain the absence of labeling of RD19s. Biotinylated probes are usually not membrane permeable and therefore a two-step labeling procedure was introduced to biotinylate in vivo labeled papain-like Cys proteases (Kaschani et al., 2009a). First, a minitagged E-64 is used for in vivo labeling. Minitags are small chemical tags (either an alkyne or azide) that do not affect cell permeability of the small molecule. After in vivo labeling, proteins are extracted under denaturing conditions and biotinylated with a minitagged biotin through “click chemistry.” Click chemistry is a copper(I)-catalyzed organic chemistry reaction that does not require enzymatic activities and can occur under denaturing conditions, thereby excluding ex vivo labeling. This two-step ABPP strategy was developed in medical research (Speers and Cravatt, 2004; Willems et al., 2011), and later introduced into plant science with E-64-based probes (Kaschani et al., 2009a). When applied on Arabidopsis cell cultures, labeling of RD19A and RD19C can now clearly be detected, as well as RDL2 and XBCP2, two other papain-like Cys proteases that were not previously detected (Richau et al., submitted; Table 1). These data indicate that many protein activities are detected only by in vivo labeling and would be missed by the analysis of labeled extracts.

In addition to DCG-04, papain-like Cys proteases also react with MVA178. MVA178 is designed for labeling the proteasome and contains a peptide consisting of three leucines, followed by a vinyl sulfone (VS) reactive group (Verdoes et al., 2008; Figure 2B). The cross-reactivity of papain-like Cys proteases for MVA178 probes is not unexpected given the fact that this probe contains a P2 = Leu and a trap for nucleophiles. Interestingly, strong papain-like Cys protease-derived signals were detected with MVA178 when Arabidopsis seedlings were labeled. Purification and identification of the labeled proteins using click chemistry revealed that these signals contain RD21A, RD19A, and RD19C (Kaschani et al., 2009a; Table 1). These data are consistent with the previously mentioned observation that in RD19A and RD19C activities can only be detected in vivo or when overexpressed (Richau et al., submitted). Moreover, labeling of Arabidopsis leaf extracts with VS-based probes results in weak signals that are absent in leaf extracts from rd21A knockout lines (Gu et al., 2010), indicating that RD21A but not RD19A or RD19C activities can be detected with VS probes in leaf extracts.

Vinyl sulfone-based probes, however, do not label all papain-like Cys proteases that can be labeled by DCG-04. AALP, for example, was not detected during MS analysis of proteins labeled with VS-based probes (Kaschani et al., 2009a; Gu et al., 2010). Furthermore, labeling of RD21A by DCG-04 can be prevented with VS-based probes, but labeling of AALP by DCG-04 is unaffected, confirming that AALP is not a target of VS-based probes (Gu et al., 2010).

The introduction of probes for ABPP of papain-like Cys proteases has made a serious impact in Arabidopsis research. ABPP using DCG-04 has been used to detect senescence-associated papain-like Cys proteases in Arabidopsis (Van der Hoorn et al., 2004; Pruzinska et al., in preparation), to show that AtSerpin1 inhibits RD21A (Lampl et al., 2010), and that heterologously expressed AVR2 from the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum affects papain-like Cys protease activities in Arabidopsis (Van Esse et al., 2008). Beyond Arabidopsis proteomes, ABPP has been very useful in studying papain-like Cys proteases in the tomato apoplast, and their inhibition by diverse pathogen-derived inhibitors (Rooney et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2007; Shabab et al., 2008; Van Esse et al., 2008; Song et al., 2009; Kaschani et al., 2010). Further studies in Arabidopsis and other plants on the regulatory roles of cystatins (Martinez et al., 2005), protein di-isomerases (Ondzighi et al., 2008), and other putative regulators of papain-like Cys proteases are likely to benefit tremendously by using ABPP.

The Proteasome

The 26S proteasome is a protein complex that resides in the cytoplasm and nucleus and degrades ubiquitinated proteins (Kurepa and Smalle, 2008). The proteasome consists of a 19S regulatory particle (RP) and a 20S core protease (CP). The inner two rings of the CP each contain three catalytic subunits having different proteolytic activities: β1 cleaves after acidic residues, while β2 cleaves after basic residues and β5 after hydrophobic residues (Kurepa and Smalle, 2008). The catalytic subunits of Arabidopsis are encoded by five genes: PBA1 (β1), PBB1 and PBB2 (β2), and PBE1 and PBE2 (β5). Since the selective degradation of substrates is thought to depend entirely on the selective ubiquitination machinery, the activity of the catalytic subunits of the proteasome itself has been poorly investigated. Studying the proteasome activity with traditional methods is also tedious, since it requires the isolation of the proteasome from tissue and the use of specific fluorogenic substrates to measure the activity of each proteasome subunit (e.g., Groll et al., 2008; Hatsugai et al., 2009). Furthermore, studies on the function of the proteasome subunits are hampered by the fact that each subunit is essential for proteasome assembly and that the proteasome is indispensable for cell survival.

The proteasome activity can be displayed with activity-based probes of three different chemotypes (Gu et al., 2010; Kolodziejek et al., 2011). The previously mentioned VS-based probes contain a peptide with three leucines and a VS reactive group (e.g., MV151, BioVS, and MVA178; Figure 2B; Kessler et al., 2001; Verdoes et al., 2006, 2008). The epoxomicin-based probe contains the tetrapeptide (Ile-Ile-Thr-Leu) and an epoxyketone reactive group (e.g., MVB003, MVB070, and MVB172; Figure 2C; Kolodziejek et al., 2011). The syrbactin-based probes contains a 12-membered ring with a reactive Michael system (e.g., RhSylA; Figure 2D; Clerc et al., 2009). All three probes label the proteasome in extracts and in living cells, but these probes differ in their characteristics. MS analysis of BioVS-labeled leaf extracts identified PBA1(β1), PBB1(β2), and PBE1(β5; Gu et al., 2010; Table 1). In vivo labeling of seedlings with MVA070 identified PBE1(β5) and PBE2(β5; Kaschani et al., 2009a) and the same subunits were identified by in vivo labeling of cell cultures with epoxomicin-based MVB070 (Kolodziejek et al., 2011; Table 1). The specific labeling of PBE1(β5) and PBE2(β5) in living cells can be explained by the fact that labeling in vivo is not saturating, since this would affect cell viability and that both VS- and epoxomicin-based probes preferentially react with β5 (PBEs; Gu et al., 2010; Kolodziejek et al., 2011).

Besides the proteasome, VS-based probes also label papain-like Cys proteases (Table 1). The property that this probe monitors different proteolytic activities in both the cytoplasm and endomembrane system can be very useful. This revealed, for example, that the frequently used proteasome inhibitor MG132 preferentially inhibits papain-like Cys proteases in vivo (Kaschani et al., 2009a), casting doubts on the previously drawn conclusions where MG132 was used to stabilize various substrates in vivo. The dual targeting property of fluorescent VS-based probes, however, puts limitations to their use in imaging since it is not known what the fluorescent signals in the cell represent.

In contrast to VS-based probes, epoxomicin-based probes are highly selective for the proteasome and have been used for imaging. When incubated with Arabidopsis cell cultures, fluorescent epoxomicin-based probes light up the cytoplasm and nucleus (Kolodziejek et al., 2011), consistent with the presumed location of the proteasome. Syrbactin-based probes are also highly selective for the proteasome and have also been used for imaging. Surprisingly, these studies revealed that fluorescent syrbactin-based probes accumulate in the nucleus of Arabidopsis cell cultures (Kolodziejek et al., 2011). One explanation for this observation could be that syrbactin-based probes target the nuclear proteasome since the properties of nuclear proteasomes may be different from those residing in the cytoplasm.

Proteasome probes are likely to affect research on the plant proteasome to a great extent. For example, ABPP of the proteasome revealed that the proteasome activity increases during salicylic acid signaling (Gu et al., 2010). This upregulated activity occurs in the cytoplasm where >90% over the cellular proteasome resides (Gu et al., 2010). Importantly, the increased proteasome activity is not associated with increased proteasome levels (Gu et al., 2010). This illustrates the added value of ABPP information since such differential activities would not be detected by traditional functional proteomic approaches. A stress-induced proteasome activity is reminiscent of the immunoproteasome described in animals which is thought to release peptides for antigen display (Goldberg et al., 2002). Furthermore, ABPP of the proteasome was used to confirm that syringolin A (SylA), a non-ribosomal peptide produced by the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a, inhibits the plant proteasome (Kolodziejek et al., 2011). Further studies revealed that SylA preferentially targets the β2 and β5 subunits and that SylA may specifically target the nuclear proteasome (Kolodziejek et al., 2011). These studies illustrate that proteasome probes will have a profound effect on studies on the localization and regulation of the Arabidopsis proteasome.

Serine Hydrolases

Ser hydrolases are a large superfamily of hydrolytic enzymes carrying an activated Ser residue in the catalytic triad. The Arabidopsis genome encodes for hundreds of Ser hydrolases, including 55 S8 subtilases, 23 S9 prolyl oligopeptidases (POPLs), 51 S10 Ser carboxypeptidase-like proteins (SCPLs), which includes acyltransferases, 11 pectin acetylesterase-like proteins (PAEs), 52 GDSL lipases, 20 carboxyesterases (CXEs), and 20 methylesterases (MESs; Kaschani et al., 2009b). The vast majority of these Ser hydrolases have not been functionally characterized, but some are involved in various biological and biochemical processes. Of the subtilases, SBT1.7/ARA12 is required for mucilage release from the seed coat (Rautengarten et al., 2008), whereas SBT6.2/TPP2 degrades peptides released by the proteasome (Book et al., 2005). The prolyl oligopeptidase-like AARE degrades N-acylated proteins in the chloroplast stroma (Yamauchi et al., 2003). SCPL8/SNG1 is an acyltransferase involved in the production of UV protectant sinapoyl malate (Lehfeldt et al., 2000), and overexpression of SCPL24/BRS1 suppresses dwarfing in brassinosteroid signaling mutants (Li et al., 2001). Furthermore, carboxylesterase CXE12 is involved in xenobiotics detoxification (Cummins et al., 2007) and methylesterases MES2 and MES3 can hydrolyze various methylated phytohormones (Vlot et al., 2008). Finally, S-formylglutathione hydrolase (SFGH) is involved in formaldehyde metabolism (Kordic et al., 2002). In conclusion, the roles of the first characterized Ser hydrolases are remarkably diverse.

The activities of Ser hydrolases can be displayed with phosphonate- and phosphate-based probes. The use of FP (Figures 2E,F; Liu et al., 1999) has been particularly powerful in medical research (Simon and Cravatt, 2010). FP probes have a small reactive fluorophosphonate group, an alkyl or polyethylene glycol linker, and various reporter tags. We have identified the targets of a biotinylated FP probe from Arabidopsis leaf extracts using on-bead tryptic digests and MudPIT analysis. After subtracting background proteins detected in the no-probe controls, 45 Ser hydrolases remained (Table 1; Kaschani et al., 2009b). Amongst the labeled proteins are six subtilases, including ARA12 and TPP2; four POPLs, including AARE; 12 SCPLs including SNG1 and BRS1; nine pectin acetyl esterases; five GDSL lipases; five carboxyesterases including CXE12; two methylesterases (MES2 and MES3); and two other Ser hydrolases (Kaschani et al., 2009b). An additional six Ser hydrolases were identified when purified labeled proteins were excised from gel (Kaschani et al., 2009b; Table 1).

The strength of Ser hydrolase profiling in the huge number of targets is also a weakness, since many labeled proteins have the same molecular weight and overlap in protein gels. Quantitative proteomic methods will be required to compare Ser hydrolase activities between different proteomes, but this approach will not facilitate high-throughput comparative analysis. To allow high-throughput screening using 1-D protein gels and fluorescent probes, we have generated selective Ser hydrolase probes. Such a selective probe was developed by replacing the fluoride leaving group by a nitrophenol leaving group. This trifunctional nitrophenol probe (TriNP; Figure 2G) is bulkier and less reactive and therefore labels a subset of the Ser hydrolases (Nickel et al., 2011; Table 1).

Another way of studying particular Ser hydrolase activities in detail is to overexpress the protein by agroinfiltration and study the labeling of this protein in extracts. This strategy has been employed to study the activity of representatives of five different Ser hydrolase classes (Kaschani et al., 2011; Table 1). Such an approach also confirmed the labeling of glycosylated SCPL8/SNG1 by FPpRh (Kaschani et al., 2009b), and of CXE12 by TriNP and RhFP (Nickel et al., 2011; Table 1).

Ser hydrolase profiling will have a tremendous impact on Arabidopsis research since this technology detects activities of hundreds of proteins that act in various biological processes. For example, several differential Ser hydrolase activities were displayed upon infection of the susceptible Arabidopsis pad3 mutant when compared to resistant plants (Kaschani et al., 2009b). Amongst these, we noticed a downregulated activity of MES2 and MES3 during infection. Since MES2 and MES3 may regulate salicylic acid (SA) levels by releasing SA from the methyl-SA conjugate (Vlot et al., 2008), the downregulation of methylase activity may be an advantage for the pathogen since this would suppress SA signaling. Importantly, the downregulation of methylesterase activity was not predicted from transcriptomic data, illustrating the added value of the ABPP approach to detect unexpected molecular mechanisms. Another recent example is the discovery of selective inhibitors of Ser hydrolases (Kaschani et al., 2011). These inhibitors were detected by screening a small set of agrochemicals that contain phosphate or phosphonate groups using fluorescent FP and NP profiling. These selective inhibitors can be used for chemical knockout experiments and for the design of next generation selective probes for Ser hydrolases.

Matrix Metalloproteases

Matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) are family M10, clan MA proteases carrying a zinc ion in the catalytic center. Plant MMPs are implicated in growth, development, and immunity (Lenger et al., 2011). MMPs reside in the cell wall, often linked to the cell membrane. The Arabidopsis genome encodes for five MMPs (Maidment et al., 1999) and at2-mmp mutant plants have several growth defects (Golldack et al., 2002). Activity-based probes for metalloproteases are distinct from the previously discussed probes since metalloproteases do not pass through a covalent intermediate with their substrates. Consequently, probes that trap the protease in the covalent intermediate state do not exist for metalloproteases. Metalloprotease probes are therefore based on reversible inhibitors, equipped with a photoreactive group that confers covalent labeling. Hydroxamate-based inhibitors are commonly used for the design of metalloprotease photoaffinity probes (e.g., Saghatelian et al., 2004). Labeling with photoaffinity probes will report on the availability of the substrate binding site, which is an important hallmark for enzyme activity (Kobe and Kemp, 1999). Hydroxamate-based inhibitors bind to the substrate binding pocket and chelate the metal ion in the active site using the hydroxamate moiety. A photoaffinity probe based on marimastat, a hydroxamate-based inhibitor, has been designed, synthesized, and tested for labeling Arabidopsis MMPs (e.g., JL01, Figure 2H, Lenger et al., 2011). Labeling with hydroxamate-based probes was confirmed for At2-MMP, At4-MMP, and At5-MMP using extracts of N. benthamiana overexpressing each protease (Lenger et al., 2011; Table 1). Further studies using fluorescent probes and membranes from (mutant) Arabidopsis plants are aimed to further establish MMP profiling and may reveal other metalloprotease classes that are targeted by hydroxamate probes.

Conclusion, and New Directions

In conclusion, using probes of six different chemotypes, 68 Arabidopsis proteins have been detected by MS analysis of probe-labeled samples from extracts (64 proteins) and upon in vivo labeling (10 proteins; Table 1). Labeling of 14 of these proteins has been confirmed by transient overexpression through agroinfiltration (Table 1). Overexpression by agroinfiltration demonstrated labeling of another eight proteins (Table 1). Thus, activities of 76 Arabidopsis proteins have been detected. Based on the fact that these proteins represent larger subfamilies, and that the probes seem to be non-selective within these families, we anticipate that at least 276 proteins can be monitored using ABPP if the right tissues and labeling conditions are applied.

The establishment of ABPP for the four classes of plant proteins described above is only the beginning. Probes have been described for phosphatases, glycosidases, cytochrome P450s, histone deacetylases, kinases, and many other proteins (Cravatt et al., 2008; Witte et al., 2011). Validation of these probes on Arabidopsis proteomes is a challenging task for the Plant Chemetics lab. Probes that have been validated and will soon be available are targeting vacuolar processing enzymes (VPEs, family C13, clan CD, 4 genes) and ATP binding proteins, including kinases (>1500 genes). Of particular interest are unbiased probes. Unbiased probes are not designed for a particular protein class but are reactive to residues in proteomes that are in an elevated reactive state. These hyperreactive residues appear often of functional importance. Cysteine residues that are hyperreactive to iodoacetamide probes, for example, are often catalytic residues, or sites for post-translational modification (Weerapana et al., 2010). We have identified a probe of a different chemotype that highlights functionally important tyrosine residues in the xenobiotic binding site of glutathione-S-transferases (Gu, Weerapana, Wang, Colby, Cravatt, Kaiser, Van der Hoorn, unpublished).

New probes come with an increased demand for improved detection technologies. Specific probes are ideal for high-throughput analysis and cell imaging, but are not available for most proteins. In contrast, broad range probes require quantitative proteomic analysis to take full advantage of the extensive target range offered by these probes. Furthermore, unbiased probes not only require the identification of the labeled protein, but also the labeling site, which will put further demands on proteomic detection methods. Comparison of activities in different proteomes is feasible by quantifying fluorescent signals. However, quantification of labeled proteins by MS is more challenging, since this requires the application of quantitative methods such as SILAC or iTRAQ (Brewis and Brennan, 2010). Isotopic tandem orthogonal proteolysis (isoTOP) is of particular interest to identify labeling sites and compare their relative amounts between two proteomes (Weerapana et al., 2010).

A third direction of ABPP expansion is aimed at the application of activity-based probes and their generated information in Arabidopsis research and beyond. Activity information should become integral to the information offered by The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR), and more probes should become accessible to the research community. The Plant Chemetics lab will continue to host visiting scientists to apply ABPP on other plant-related research questions, and probes will become available through a website that offers the probes for prices that would cover re-synthesis.

Thus, further development using new probes, detection technologies, and the availability of the probes and technology to the research community is going to display an increasing number of proteome activities of Arabidopsis and beyond.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the DFG grants HO 3983/4-1; KA 2894/1-1; and SCHM 2476/2-1 within the framework of the Arabidopsis Functional Genomics Network (AFGN).

References

- Ahmed S. U., Rojo E., Kovaleva V., Venkataraman S., Dombrowski J. E., Matsuoka K., Raikhel N. V. (2000). The plant vacuolar sorting receptor AtELP is involved in transport of NH(2)-terminal propeptide-containing vacuolar proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1335–1344 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avci U., Petzold H. E., Ismail I. O., Beers C. P., Haigler C. H. (2008). Cysteine proteases XCP1 and XCP2 aid micro-autolysis within the intact central vacuole during xylogenesis in Arabidopsis roots. Plant J. 56, 303–315 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers E. P., Jones A. M., Dickerman A. W. (2004). The S8 serine, C1A cysteine and A1 aspartic protease families in Arabidopsis. Phytochemistry 65, 43–58 10.1016/j.phytochem.2003.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernoux M., Timmers T., Jauneau A., Briere C., De Wit P. J. G. M., Marco Y., Deslandes L. (2008). RD19, an Arabidopsis cysteine protease required for RRS1-R-mediated resistance, is relocalized to the nucleus by the Ralstonia solanacearum PopP2 effector. Plant Cell 20, 2252–2264 10.1105/tpc.108.058685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Book A. J., Yang P., Scalf M., Smith L. M., Vierstra R. D. (2005). Tripeptidyl peptidase II. An oligomeric protease complex from Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138, 1046–1057 10.1104/pp.104.057406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis I. A., Brennan P. (2010). Proteomic technologies for the global identification and quantification of proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 80, 1–44 10.1016/B978-0-12-381264-3.00001-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang K. P., Niessen S., Saghatelian A., Cravatt B. F. (2006). An enzyme that regulates ether lipid signaling pathways in cancer annotated by multidimensional profiling. Chem. Biol. 13, 1041–1050 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc J., Florea B. I., Kraus M., Groll M., Huber R., Bachmann A. S., Dudler R., Driessen C., Overkleeft H. S., Kaiser M. (2009). Syringolin A selectively labels the 20 S proteasome in murine EL4 and wild-type and bortezomib-adapted leukaemic cell lines. Chembiochem 10, 2638–2643 10.1002/cbic.200990072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cravatt B. F., Wright A. T., Kozarich J. W. (2008). Activity-based protein profiling: from enzyme chemistry to proteomic chemistry. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 383–414 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins I., Landrum M., Steel P. G., Edwards R. (2007). Structure activity studies with xenobiotic substrates using carboxylesterases isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 68, 811–818 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. J., Cravatt B. F. (2006). Mechanism-based profiling of enzyme families. Chem. Rev. 106, 3279–3301 10.1021/cr050288g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A. L., Cascio P., Saric T., Rock K. L. (2002). The importance of the proteasome and subsequent proteolytic steps in the generation of antigenic peptides. Mol. Immunol. 39, 147–164 10.1016/S0161-5890(02)00098-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golldack D., Popova O. V., Dietz K. J. (2002). Mutation of the matrix metalloproteinase At2-MMP inhibits growth and causes late flowering and early senescence in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5541–5547 10.1074/jbc.M106197200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum D., Medzihradszky K. F., Burlingame A., Bogyo M. (2000). Epoxide electrophiles as activity-dependent cysteine protease profiling and discovery tools. Chem. Biol. 7, 569–581 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum D. C., Arnold W. D., Lu F., Hayrapetian L., Baruch A., Krumrine J., Toba S., Chehade K., Bromme D., Kuntz I. D., Bogyo M. (2002). Small molecule affinity fingerprinting: a tool for enzyme family subclassification, target identification, and inhibitor design. Chem. Biol. 9, 1085–1094 10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00238-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll M., Schellenberg B., Bachmann A. S., Archer C. R., Huber R., Powell T. K., Lindow S., Kaiser M., Dudler R. (2008). A plant pathogen virulence factor inhibits the eukaryotic proteasome by a novel mechanism. Nature 10, 755–758 10.1038/nature06782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C., Kolodziejek I., Misas-Villamil J. C., Shindo T., Colby T., Verdoes M., Richau K. H., Schmidt J., Overkleeft H. S., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2010). Proteasome activity profiling: a simple, robust and versatile method revealing subunit-selective inhibitors and cytoplasmic, defence-induced proteasome activities. Plant J. 62, 160–170 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsugai N., Iwasaki S., Tamura K., Kondo M., Fuji K., Ogasawara K., Nishimura M., Hara-Nishimura I. (2009). A novel membrane-fusion mediated plant immunity against bacterial pathogens. Genes Dev. 23, 2449–2454 10.1101/gad.1825209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessani N., Humphrey M., McDonald W. H., Niessen S., Masuda K., Gangadharan B., Yates J. R., Mueller B. M., Cravatt B. F. (2004). Carcinoma and stromal enzyme activity profiles associated with breast tumor growth in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13756–13761 10.1073/pnas.0404727101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessani N., Liu Y., Humphrey M., Cravatt B. F. (2002). Enzyme activity profiles of the secreted and membrane proteome that depict cancer cell invasiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 10335–10349 10.1073/pnas.162187599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessani N., Niessen S., Wei B. Q., Nicolau M., Humphrey M., Ji Z., Han W., Noh D. Z., Zates J. R., Jeffrey S. S., Cravatt B. F. (2005a). A streamlined platform for high-content functional proteomics of primary human specimens. Nat. Methods 2, 691–697 10.1038/nmeth778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessani N., Young J. A., Diaz S. L., Patricelli M. P., Varki A., Cravatt B. F. (2005b). Class assignment of sequence-unrelated members of enzyme superfamilies by activity-based protein profiling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 44, 2400–2403 10.1002/anie.200463098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschani F., Nickel S., Pandey B., Cravatt B. F., Kaiser M., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2011). Selective inhibition of plant serine hydrolases by agrochemicals revealed by competitive ABPP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschani F., Shabab M., Bozkurt T., Shindo T., Schornack S., Gu C., Ilyas M., Win J., Kamoun S., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2010). An effector-targeted protease contributes to defense against Phytophthora infestans and is under diversifying selection in natural hosts. Plant Physiol. 154, 1794–1804 10.1104/pp.110.158030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschani F., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2007). Small molecule approaches in plants. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11, 88–98 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschani F., Verhelst S. H. L., Van Swieten P. F., Verdoes M., Wong C.-S., Wang Z., Kaiser M., Overkleeft H. S., Bogyo M., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2009a). Minitags for small molecules: detecting targets of reactive small molecules in living plant tissues using “click-chemistry.” Plant J. 57, 373–385 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03683.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschani F., Gu C., Niessen S., Hoover H., Cravatt B. F., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2009b). Diversity of serine hydrolase activities of non-challenged and Botrytis-infected Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 1082–1093 10.1074/mcp.M800494-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler B. M., Tortorella D., Altun M., Kisselev A. F., Fiebiger E., Hekking B. G., Ploegh H. L., Overkleeft H. S. (2001). Extended peptide-based inhibitors efficiently target the proteasome and reveal overlapping specificities of the catalytic β-subunits. Chem. Biol. 8, 913–929 10.1016/S1074-5521(01)00069-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B., Kemp B. E. (1999). Active-site-directed protein regulation. Nature 402, 373–376 10.1038/46478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejek I., Misas-Villamil J. C., Kaschani F., Clerc J., Gu C., Krahn D., Niessen S., Verdoes M., Willems L. I., Overkleeft H. S., Kaiser M., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2011). Proteasome activity imaging and profiling characterizes bacterial effector syringolin A. Plant Physiol. 155, 477–489 10.1104/pp.110.163733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziejek I., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2010). Mining the active plant proteome in plant science and biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21, 225–233 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordic S., Cummins I., Edwards R. (2002). Cloning and characterization of an S-formylglutathione hydrolase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 399, 232–238 10.1006/abbi.2002.2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurepa J., Smalle J. A. (2008). Structure, function and regulation of plant proteasomes. Biochimie 90, 324–335 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampl N., Budai-Hadrian O., Davydov O., Joss T. V., Harrop S. J., Curmi P. M. G., Roberts T. H., Fluhr R. (2010). Arabidopsis AtSerpin, crystal structure and in vivo interaction with its target protease responsive to desiccation-21 (RD21). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13550–13560 10.1074/jbc.M109.095075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehfeldt C., Shirley A. M., Meyer K., Ruegger M. O., Cusumano J. C., Viitanen P. V., Strack D., Chapple C. (2000). Cloning of the SNG1 gene of Arabidopsis reveals a role for a serine carboxypeptidase-like protein as an acyltransferase in secondary metabolism. Plant Cell 12, 1295–1306 10.2307/3871130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenger J., Kaschani F., Lenz T., Dalhoff C., Villamor J. G., Koster H., Sewald N., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2011). Labeling and enrichment of Arabidopsis thaliana matrix metalloproteases using an active-site directed, marimastat-based photoreactive probe. Bioorg. Med. Chem. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D., Hardouin C., Boger D. L., Cravatt B. F. (2003). Discovering potent and selective reversible inhibitors of enzymes in complex proteomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 687–691 10.1038/nbt826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lease K. A., Tax F. E., Walker J. C. (2001). BRS1, a serine carboxypeptidase, regulates BRI1 signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5916–5921 10.1073/pnas.251547198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Patricelli M. P., Cravatt B. F. (1999). Activity-based protein profiling: the serine hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14694–14699 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen M. A., Derzugina E. I., Niessen S., Cravatt B. F., Quiglez J. P. (2006). Activity-based protein profiling implicates urokinase activation as a key step in human fibrosarcoma intravasation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15997–16005 10.1074/jbc.M601223200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidment J. M., Moore D., Murphy G. P., Murphy G., Clark I. M. (1999). Matrix metalloproteinase homologues from Arabidopsis thaliana. Expression and activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34706–34710 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez M., Abraham Z., Diaz I. (2005). Comparative phylogenetic analysis of cystatin gene families from Arabidopsis, rice and barley. Mol. Genet. Genomics 273, 423–432 10.1007/s00438-005-1147-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan H., Gilroy E. M., Yun B. W., Birch P. R., Loake G. J. (2009). Functional redundancy in the Arabidopsis cathepsin B gene family contributes to basal defence, the hypersensitive response and senescence. New Phytol. 183, 408–418 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02865.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel S., Kaschani F., Colby T., Van der Hoorn R. A. L., Kaiser M. (2011). A para-nitrophenol phosphonate probe labels distinct serine hydrolases in Arabidopsis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondzighi C. A., Christopher D. A., Cho E. J., Chang S. C., Staehelin L. A. (2008). Arabidopsis protein disulfide isomerase-5 inhibits cysteine proteases during trafficking to vacuoles before programmed cell death of the endothelium in developing seeds. Plant Cell 20, 2205–2220 10.1105/tpc.108.058339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otequi M. S., Noh Y. S., Martinez D. E., Vila Petroff M. G., Staehelin L. A., Amasino R. M., Guiamet J. J. (2005). Senescence-associated vacuoles with intense proteolytic activity develop in leaves of Arabidopsis and soybean. Plant J. 41, 831–844 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patricelli M. P., Giang D. K., Stamp L. M., Burbaum J. J. (2001). Direct visualization of serine hydrolase activities in complex proteomes using fluorescent active site-directed probes. Proteomics 1, 1067–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri A. W., Bogyo M. (2009). Using small molecules to dissect mechanisms of microbial pathogenesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 4, 603–616 10.1021/cb9001409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautengarten C., Usadel B., Neumetzler L., Hartmann J., Bussis D., Altmann T. (2008). A subtilisin-like serine protease essential for mucilage release from Arabidopsis seed coats. Plant J. 54, 466–480 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings N. D., Barrett A. J., Bateman A. (2010). MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D227–D233 10.1093/nar/gkp971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richau K. H., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2011). Studies on plant-pathogen interactions using activity-based proteomics. Curr. Proteomics 7, 328–336 10.2174/157016410793611800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney H., Van’t Klooster J., Van der Hoorn R. A. L., Joosten M. H. A. J., Jones J. D. G., De Wit P. J. G. M. (2005). Cladosporium Avr2 inhibits tomato Rcr3 protease required for Cf-2-dependent disease resistance. Science 308, 1783–1789 10.1126/science.1111404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadaghiani A. M., Verhelst S. H. L., Bogyo M. (2007). Tagging and detection strategies for activity-based proteomics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11, 20–28 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghatelian A., Jessani N., Joseph A., Humphrey M., Cravatt B. F. (2004). Activity-based probes for the proteomic profiling of metalloproteases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10000–10005 10.1073/pnas.0402784101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabab M., Shindo T., Gu C., Kaschani F., Pansuriya T., Chintha R., Harzen A., Colby T., Kamoun S., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2008). Fungal effector protein AVR2 targets diversifying defence-related Cys proteases of tomato. Plant Cell 20, 1169–1183 10.1105/tpc.107.056325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon G. M., Cravatt B. F. (2010). Activity-based proteomics of enzyme superfamilies: serine hydrolases as a case study. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11051–11055 10.1074/jbc.R109.097600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Win J., Tian M., Schornack S., Kaschani F., Muhammad I., Van der Hoorn R. A. L., Kamoun S. (2009). Apoplastic effectors secreted by two unrelated eukaryotic plant pathogens target the tomato defense protease Rcr3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1654–1659 10.1073/pnas.0810352106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speers A. E., Cravatt B. F. (2004). Profiling enzyme activities in vivo using click chemistry methods. Chem. Biol. 11, 535–546 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian M., Win J., Song J., Van der Hoorn R. A. L., Van der Knaap E., Kamoun S. (2007). A Phytophthora infestans cystatin-like protein interacts with and inhibits a tomato papain-like apoplastic protease. Plant Physiol. 143, 364–277 10.1104/pp.106.090050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth R., Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2010). Emerging principles in plant chemical genetics. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 81–88 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hoorn R. A. L. (2008). Plant proteases: from phenotypes to molecular mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 191–223 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hoorn R. A. L., Kaiser M. (2011). Probes for activity-based profiling of plant proteases. Physiol. Plant. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Hoorn R. A. L., Leeuwenburgh M. A., Bogyo M., Joosten M. H. A. J., Peck S. C. (2004). Activity profiling of papain-like cysteine proteases in plants. Plant Physiol. 135, 1170–1178 10.1104/pp.104.041467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Esse H. P., van’t Klooster J. W., Bolton M. D., Yadeta K. A., van Baarlen P., Boeren S., Vervoort J., de Wit P. J. G. M., Thomma B. P. H. J. (2008). The Cladosporium fulvum virulence protein Avr2 inhibits host proteases required for basal defense. Plant Cell 20, 1948–1963 10.1105/tpc.108.059394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoes M., Florea B. I., Hillaert U., Willems L. I., Van der Linden W. A., Saeheng M., Filippov D. V., Kisselev A. F., Van der Marel G. A., Overkleeft H. S. (2008). Azido-BODIPY acid reveals quantitative Staudinger-Bertozzi ligation in two-step activity-based proteasome profiling. Chembiochem 9, 1735–1738 10.1002/cbic.200800231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoes M., Florea B. I., Menendez-Benito V., Maynard C. J., Witte M. D., Van der Linden W. A., Van den Nieuwendijk A. M., Hofmann T., Berkers C. R., Van Leeuwen F. W., Groothuis T. A., Leeuwenburgh M. A., Ovaa H., Neefjes J. J., Filippov D. V., Van der Marel G. A., Dantuma N. P., Overkleeft H. S. (2006). A fluorescent broad-spectrum proteasome inhibitor for labeling proteasomes in vitro and in vivo. Chem. Biol. 13, 1217–1226 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlot A. C., Liu P. P., Cameron R. K., Park S. W., Yang Y., Kumar D., Zhou F., Padukkavidana T., Gustafsson C., Picherski E., Klessig D. F. (2008). Identification of likely orthologs of tobacco salicylic acid binding protein 2 and their role in systemic acquired resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 53, 445–456 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03618.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerapana E., Wang C., Simon G. M., Richter F., Khare S., Dillon M. B. D., Bachovchin D. A., Mowen K., Baker D., Cravatt B. F. (2010). Quantitative reactivity profiling predicts functional cysteines in proteomes. Nature 468, 790–795 10.1038/nature09472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems L. I., Van der Linden W. A., Li N., Li K. L., Liu N., Hoogendoorn S., Van der Marel G. A., Florea B. I., Overkleeft H. S. (2011). Bioorthogonal chemistry: applications in activity-based protein profiling. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 718–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte M. D., Van der Marel G. A., Aerts J. M., Overkleeft H. S. (2011). Irreversible inhibitors and activity-based probes as research tools in chemical glycobiology. Org. Biomol. Chem. 9, 5908–5926 10.1039/c1ob05531c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Matsushima R., Nishimura M., Hara-Nishimura I. (2001). A slow maturation of a cysteine protease with a granulin domain in the vacuoles of senescing Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 127, 1626–1634 10.1104/pp.900002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi Y., Eijri Y., Tanaka K. (2003). Identification and biochemical characterization of plant acylamino acid-releasing enzyme. J. Biochem. 134, 251–257 10.1093/jb/mvg138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]