Abstract

Global change can greatly affect plant populations both directly by influencing growing conditions and indirectly by maternal effects on development of offspring. More information is needed on transgenerational effects of global change on plants and their interactions with pathogens. The current study assessed potential maternal effects of atmospheric CO2 enrichment on performance and disease susceptibility of first-generation offspring of the Mediterranean legume Onobrychis crista-galli. Mother plants were grown at three CO2 concentrations, and the study focused on their offspring that were raised under common ambient climate and CO2. In addition, progeny were exposed to natural infection by the fungal pathogen powdery mildew. In one out of 3 years, offspring of high-CO2 treatments (440 and 600 ppm) had lower shoot biomass and reproductive output than offspring of low-CO2 treatment (280 ppm). Disease severity in a heavy-infection year was higher in high-CO2 than in low-CO2 offspring. However, some of the findings on maternal effects changed when the population was divided into two functionally diverging plant types distinguishable by flower color (pink, Type P; white, Type W). Disease severity in a heavy-infection year was higher in high-CO2 than in low-CO2 progeny in the more disease-resistant (Type P), but not in the more susceptible plant type (Type W). In a low-infection year, maternal CO2 treatments did not differ in disease severity. Mother plants of Type P exposed to low CO2 produced larger seeds than all other combinations of CO2 and plant type, which might contribute to higher offspring performance. This study showed that elevated CO2 potentially exerts environmental maternal effects on performance of progeny and, notably, also on their susceptibility to natural infection by a pathogen. Maternal effects of global change might differently affect functionally divergent plant types, which could impact population fitness and alter plant communities.

Keywords: atmospheric CO2 enrichment, biomass production, environmental maternal effects, fungal pathogen, natural population, Onobrychis crista-galli, plant disease, plant type

Introduction

Research during past decades has shown that atmospheric CO2-enrichment influences a wide range of plant processes at the species, population, and community level. This includes growth and reproduction, biomass production, carbon sequestration, and shifts in community composition and species diversity (Körner, 2006). Moreover, interactions of plants with other organisms, such as pathogens were affected by CO2 enrichment. The infection rate with plant pathogens and the disease progress can be altered by elevated CO2 due to changes in plant physiology, morphology, anatomy, and phenology (Chakraborty et al., 2000; Mcelrone et al., 2005; Burdon et al., 2006; Garrett et al., 2006). In a majority of studies, elevated CO2 significantly affected plant-pathogen relationships by either increasing or decreasing infection rate and disease severity (see e.g., Chakraborty et al., 2000; Mitchell et al., 2003; Mcelrone et al., 2005; Plessl et al., 2007).

Research mainly focused on plants growing directly under CO2 enrichment, and less attention was paid to consequences for performance of offspring. Performance of progenies depends on the one hand on their genotypic characteristics and on environmental conditions during plant development, but on the other hand also on maternal effects, i.e., the influence of the maternal genotype or phenotype on the offspring phenotype beyond the chromosomal contribution from each parent (Roach and Wulff, 1987; Wolf and Wade, 2009). Maternal effects are, in part, the consequence of the environmental conditions experienced by mother plants, including during seed maturation (Wulff, 1995). Environmental maternal effects result from maternal provision of seed storage-compounds and from tissues of maternal origin surrounding embryo and endosperm, such as seed coat and accessory seed structures (Roach and Wulff, 1987; Rossiter, 1996; Donohue and Schmitt, 1998). In addition, the maternal environment can affect traits in the mother plant that influence offspring trait-expression (Galloway, 2005), e.g., by inherited epigenetic modifications (Molinier et al., 2006).

Maternal effects have been shown to affect a wide array of offspring traits, including plant growth and development, plant defense against herbivory, acclimation to abiotic stresses, and life history traits (Rossiter, 1996; Agrawal, 2002). Environmental maternal effects of elevated CO2 affected several components of offspring performance, including germination, growth, and biomass production. Success of and time to germination and emergence of seeds that matured at elevated CO2 were significantly modified in a few species (Farnsworth and Bazzaz, 1995; Andalo et al., 1996; Grünzweig and Körner, 2000; Edwards et al., 2001; Thürig et al., 2003; Hovenden et al., 2008). Subsequent production of shoot and root biomass was ambivalent, and both increased and decreased biomass was observed in high-CO2 compared with low-CO2 progenies when grown at ambient CO2 (Fordham et al., 1997; Huxman et al., 1998; Edwards et al., 2001).

Maternal effects on plant–pathogen interactions have rarely been shown in any system. In a tropical tree, the frequency of damping-off disease of seedlings depended on seed dispersal and seedling density (Augspurger, 1983), which can be influenced by the provision of dispersal traits by the mother plant (Donohue and Schmitt, 1998). Genetic studies in corn revealed unspecified maternal effects on resistance to Fusarium seedling blight and ear rot (Lunsford et al., 1976; Gendloff et al., 1986). In Arabidopsis thaliana, an elicitor of plant defense (a treatment applied to the mother plant only) induced genetic changes (enhanced somatic homologous recombination) that were passed down to the progeny, suggesting an epigenetic mode of inheritance (Molinier et al., 2006). To the best of my knowledge, maternal effects on offspring susceptibility to pathogens have not been shown in response to global-change drivers so far.

For a number of species, significant CO2 × genotype interactions for biomass and reproductive output were detected, while most species did not show such interactions (Lau et al., 2007). Maternal effects of CO2 enrichment were rarely studied on different genotypes within a species or on different plant types within a population. Maternal CO2 concentration interacted significantly with genotype for germination success in offspring of wild populations of A. thaliana that originated from different environments (Andalo et al., 1996). Some genotypes germinated at lower rates when seeds were produced under high maternal CO2 concentration, while for other genotypes no differences among maternal CO2 treatments were observed.

The objective of the current study was to assess potential maternal effects of elevated CO2 on performance of offspring of the Mediterranean legume Onobrychis crista-galli (L.) Lam. (cock's comb sainfoin) under ambient climate and CO2 conditions. Mother plants were grown in an original experiment with species-rich assemblages under three different CO2 concentrations that spanned a range between pre-industrial and future levels (280, 440, and 600 ppm CO2). O. crista-galli was the most responsive species to CO2 enrichment in the original experiment, with an increase of 30–150% in number and mass of fruits and seeds per individual at elevated CO2 (Grünzweig and Körner, 2001a). Specific aims of the study were (1) assessing maternal effects of elevated CO2 on seedling emergence, growth, and development of progenies with and without consideration of functionally diverging plants types within the same population of O. crista-galli; (2) analyzing susceptibility of progenies to the fungal disease powdery-mildew under natural infection.

Materials and Methods

Onobrychis crista-galli is a common annual legume in the deserts, shrublands, and grasslands of the Middle East and northern Africa. It is one of the larger annual legumes in the northern Negev of Israel, and has a low to intermediate degree of nodulation with symbiotic dinitrogen fixing bacteria under natural conditions (Hely and Ofer, 1972; Atallah et al., 2008). The species was characterized as being relatively mesic according to an analysis of reproductive traits along an aridity gradient (Ehrman and Cocks, 1996).

Seeds of O. crista-galli were collected at the Lehavim Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) site in the semi-arid northern Negev, Israel (400 m a.s.l., 31º21′N, 34º51′E; Mediterranean climate, with mild winters and 300 mm precipitation, hot summers, and no rain) in 1996–1997. Mother plants were grown on native light lithosol as part of a species-rich community in model ecosystems (large containers of 100 cm × 70 cm surface area and 35 cm depth) subjected to three CO2 treatments (280 ppm, pre-industrial CO2; 440 ppm, CO2 concentration expected by the year ∼2025 according to the IPCC SRES scenario A1B; 600 ppm CO2, expected by the years 2060–2075; IPCC, 2007). Model ecosystems were placed in growth chambers, and were subjected to a dynamic climate simulation over the entire growing season of 5 months. Climate simulations included weekly adjustment of light intensity, temperature, precipitation, and relative air humidity to the average natural conditions at the Lehavim LTER site (for more details see Grünzweig and Körner, 2001b). CO2 treatments were replicated by three model ecosystems in each of the three growth chambers (one chamber per CO2 treatment). Chamber effects were minimized by a random weekly reallocation of CO2 treatments to chambers (Grünzweig and Körner, 2001b). Pseudoreplication could be prevented by weekly rearranging position and orientation of model ecosystems within chambers. Reallocation of chambers and repositioning of model ecosystems were performed 23 times in total during the experiment. Mother plants did not show any disease symptoms. Following seed maturation at the end of the growing season 1997, seeds were collected, stored for 28 months at room temperature and frozen thereafter at −20°C for preservation.

This seed stock was used for experiments during the growing seasons of 2005, 2006, and 2007, i.e., each year seeds were randomly chosen from the same stock to study first-generation offspring performance. Each year, seeds from the three original CO2 treatments were slightly scarified with sandpaper, sown into soil collected at the Lehavim LTER site, and offspring seedlings were grown under ambient CO2 conditions (∼380 ppm). Plants were grown in trays with conical compartments of 13 cm depth and 420 cm3 volume in 2005 and of 15 cm depth and 320 cm3 volume in 2006 and 2007 (one seedling per compartment; Quickpot, HerkuPlast-Kubern, Ering/Inn, Germany). Trays were placed in a net-house facility at the Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, and subjected to ambient conditions, except for precipitation. Daily average temperature during the main growing season varied between 12.5°C in January and 18.0°C in April, with average monthly temperatures varying among years by up to 1.5°C. The net-house decreased photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) by about 10% relative to total incoming PPFD. To adjust precipitation to the semi-arid conditions at the Lehavim LTER site, rainfall was intercepted by a transparent polyethylene sheet that was set up only during major rain events. Water was added to trays at 4-days intervals in 2005 and at 6-day intervals in 2006 and 2007. These intervals allowed transient surface dry-out of the soil as common under field conditions (Grünzweig and Körner, 2001b). Plants were sown in January each year, and were harvested close to peak season (but after fruit set) in 2005 and 2006, and at the end of the season upon plant dehydration in 2007.

In addition to maternal CO2, the inclusion of plant type in the experimental design was tested. The following two plant types were detected in the offspring population: a pink-flowering type and a white-flowering type, designated “Type P,” and “Type W,” respectively (Figure 1). Both plant types belonged to the variety O. crista-galli ssp. crista-galli var. crista-galli (L.) Lam. (Heyn, 1962). In addition to petal color, plant types proved to differ in various characteristics, such as seed size, time to seedling emergence, time to anthesis, disease severity, biomass, and fecundity (see Results). Plant type as a source of variation was not considered in the original CO2-enrichment experiment, although both types were present in all model ecosystems. Seeds produced by mother plants at the end of the original experiment were collected in bulk from each model ecosystem, irrespective of plant type (Grünzweig and Körner, 2001b). Therefore, identity of seeds regarding plant type was unknown in the current study, and assignment of plant type to maternal CO2 concentration was random. In all cases, each plant-type covered at least one-third of all plants per experimental year and maternal CO2 treatment (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Onobrychis crista-galli (cock's comb sainfoin) plant with developing fruits (A), white-flowering plant type showing symptoms of powdery mildew (B), pink-flowering plant type (C).

Table 1.

Fraction of plant types randomly allocated to maternal CO2 treatments in the three experimental years.

| Maternal CO2 (ppm) | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type P | Type W | Type P | Type W | Type P | Type W | |

| 280 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.67 | 0.33 |

| 440 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 0.65 |

| 600 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.62 |

Seed size was recorded as air-dry mass for each individual seed after seed moisture was adjusted in a growth chamber at 22–24°C and 40–60% relative humidity for 24 h. Seedling emergence was determined at the first aboveground appearance of the cotyledons. Anthesis was defined as opening of the first flower of an individual plant. Biomass was not analyzed in 2007 because plants were harvested only after desiccation and seed maturation to record offspring seed size.

Powdery-mildew naturally infected seedlings in all 3 years. The pathogen was identified as Erysiphe martii Lév, which widely infects Onobrychis plants of different species in Israel (Rayss, 1940) and elsewhere (Mühle and Frauenstein, 1970; Karaboz and öner, 1982; Amano, 1986). In a preliminary test in 2005, disease severity was estimated for each leaf of each plant by rating cover of fungal mat on an increasing scale from 0 to 3 (from no cover to full cover by fungal mat, respectively) at one point in time. Disease severity was more profoundly assessed in 2006 and 2007 by assigning a severity value to each leaf at various measuring dates according to the following scale: 0 (0% leaf cover by fungal mat), 0.05 (1–5%), 0.2 (6–20%), 0.5 (21–50%), 1.0 (51–100%). For both ways of rating fungal mat cover, the values of all leaves of a plant were added up and divided by the number of leaves to express disease severity at the plant level on a scale ranging from 0 to 1. Area under disease-progress curves (AUDPC) was calculated over the period between disease onset (i = 1) and the last record of disease progress (i = n; Figure 2), as follows (Shaner and Finney, 1977):

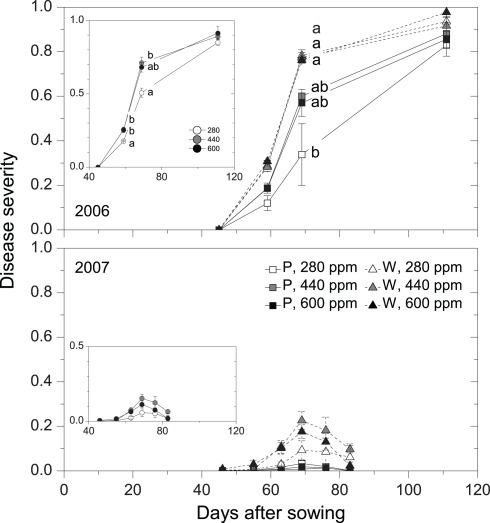

Figure 2.

Disease progress as affected by maternal CO2 concentration (280, 440, 600 ppm) and plant type (P = pink flowering, W = white flowering) in 2006 and 2007 (Case 2). Inserts show disease-progress affected by maternal CO2 only (Case 1). Disease severity was determined for each leaf and was subsequently added up for all leaves of a plant and expressed on a scale ranging between 0 and 1 (see Materials and Methods). Mean ± 1 SE, n = 3 model ecosystems. Non-identical letters indicate statistically significant differences among combinations of maternal CO2 treatments and plant type (main panels) or among maternal CO2 concentrations (inserts) as analyzed by the Tukey–Kramer HSD test (P ≤ 0.05 within mixed models, see Table 4). Sixty-three days after sowing in 2007, disease severity was significantly higher in 440-ppm progenies of plant-type W compared with all Type P progenies (Tukey–Kramer HSD test, P ≤ 0.05).

| (1) |

where DSi is disease severity at the end of period i and Li is the length of period i in days. Disease onset was defined here as the day when symptoms became visible on leaves.

Data were analyzed for the following two cases: Case 1 assumed a homogeneous population without diverging plant types. This is the common case for most studies where no phenotypic or genetic information exists to allow splitting up populations into different plant types. Case 2 shows the current situation where distinct plant types can be defined in the population, here by flower color. Plant performance and disease severity were analyzed by one-way mixed-model ANOVA for Case 1 and two-way mixed-model ANOVA for Case 2. The one-way ANOVA for Case 1 included maternal CO2 as fixed factor and model ecosystem nested within maternal CO2 as random factor. The random factor was a consequence of sampling seeds from the three model ecosystems per maternal CO2 treatment in the original CO2-enrichment experiment. To test potential interactions of maternal CO2 with plant type in Case 2, a two-way ANOVA was performed that included maternal CO2, plant type and their interactions as fixed factors, and model ecosystem nested within maternal CO2 and the interaction of model ecosystem and plant type as random factors. Homogeneity of variance was tested by Bartlett's test, and data transformation (Box–Cox) was carried out where necessary. In disease-progress studies, time was added as an additional fixed factor to the analysis. Multiple comparisons among levels of fixed factors were performed by the Tukey–Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD) test. ANCOVAs with seed size as covariate showed the same results as the above mentioned ANOVAs, and were not presented here (the covariate was statistically non-significant in almost all analyses). Disease incidence (proportion of diseased plants) was analyzed by a Chi-square test.

Sample size (number of individuals per model ecosystem) varied greatly according to seed availability. For Case 1 (plant type not included as a factor), sample size ranged from 27 to 36 for determination of seed size in mother plants, from 3 to 12 for variables measured in 2005 and 2007, and from 11 to 21 in 2006. Sample size for Case 2 (plant type included as a factor) was lower. In 2005, plant type was unknown for 25% of the individuals because of technical reasons. To enable a comparison with case 2, the analysis of case 1 in 2005 included only individuals of known plant type, unless stated differently. Statistical analysis was conducted by JMP 7.0.1 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Case 1 (disregarding plant types)

Case 1 simulates the common scenario where no diverging plant types are known. When plant types were disregarded maternal CO2 had a significant impact on offspring biomass and fruit production and on disease severity. Shoot biomass was lower by 17% on average in high-CO2 progenies (maternal CO2 concentrations of 440 and 600 ppm) than in low-CO2 progenies (maternal CO2 concentration of 280 ppm) at peak season in 2005 (Tables 2 and 3). High-CO2 offspring also produced 15% less fruits than low-CO2 offspring. In 2006, when plants were growing in smaller compartments than in 2005 (see Materials and Methods), CO2 progenies did not differ in shoot biomass. Maternal CO2 did not significantly affect phenology (emergence, anthesis) and reproductive output (fruit and seed production) in 2006 and 2007 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Seed size in mother plants and offspring performance for the common scenario of Case 1 where plant types are indistinguishable and for Case 2 with distinct plant types.

| Variable | Exp. Year | Case 1 (disregarding plant types) | Case 2 (distinguishing between plant types) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant-type P | Plant-type W | |||||||||

| 280 ppm | 440 ppm | 600 ppm | 280 ppm | 440 ppm | 600 ppm | 280 ppm | 440 ppm | 600 ppm | ||

| MOTHER PLANTS | ||||||||||

| Seed size (mg) | Pre-exp. | 11.1 (0.8) | 9.4 (0.5) | 9.5 (0.3) | 12.0 (0.9)a | 10.1 (0.6)b | 9.6 (0.4)b | 9.6 (0.9)b | 8.9 (0.4)b | 9.5 (0.6)b |

| OFFSPRING | ||||||||||

| Seedling emergence (days after sowing) | 2006 | 5.9 (0.2) | 5.9 (0.1) | 6.3 (0.6) | 5.8 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.4) | 5.3 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.2) | 6.5 (0.6) | 6.8 (0.8) |

| 2007 | 10.3 (0.7) | 11.5 (0.3) | 10.8 (0.9) | 9.5 (0.7) | 11.0 (1.0) | 10.0 (0.7) | 12.3 (1.3) | 11.7 (0.4) | 11.3 (0.9) | |

| Anthesis (days after sowing) | 2006 | 71.0 (1.4) | 73.2 (1.9) | 73.1 (0.7) | 68.9 (0.6) | 70.1 (2.6) | 71.3 (1.4) | 72.8 (2.9) | 75.1 (1.0) | 74.2 (0.6) |

| 2007 | 74.0 (0.8) | 74.2 (1.4) | 74.0 (0.3) | 73.0 (1.6) | 73.8 (1.4) | 73.1 (0.6) | 75.1 (0.3) | 74.4 (1.4) | 74.2 (0.5) | |

| Shoot biomass (mg per individual) | 2005 | 676 (49)a | 554 (6)b | 564 (8)b | 756 (40) | 644 (39) | 664 (62) | 585 (87) | 484 (26) | 484 (11) |

| 2006 | 338 (17) | 318 (46) | 311 (22) | 384 (6) | 403 (41) | 391 (28) | 241 (32) | 269 (25) | 243 (23) | |

| Number of fruits per individual plant | 2005 | 3.94 (0.22)a | 3.35 (0.13)b | 3.33 (0.05)ab | 4.50 (0.29) | 3.28 (0.15) | 2.92 (0.46) | 3.44 (0.29) | 3.40 (0.10) | 3.67 (0.44) |

| 2006 | 1.71 (0.12) | 1.56 (0.24) | 1.68 (0.16) | 1.90 (0.10) | 2.04 (0.27) | 2.02 (0.23) | 1.49 (0.15) | 1.13 (0.09) | 1.34 (0.05) | |

| 2007 | 3.89 (0.32) | 3.98 (0.30) | 4.08 (0.04) | 3.53 (0.11) | 3.92 (0.36) | 3.72 (0.17) | 4.67 (0.88) | 4.02 (0.27) | 4.43 (0.20) | |

| Number of seeds per individual plant | 2006 | 4.71 (0.26) | 4.28 (0.70) | 4.15 (0.42) | 5.40 (0.28) | 5.92 (0.71) | 5.42 (0.34) | 3.69 (0.54) | 2.94 (0.14) | 2.99 (0.31) |

| 2007 | 9.07 (0.69) | 9.03 (0.56) | 9.40 (0.23) | 8.89 (0.46) | 10.58 (1.18) | 9.80 (0.61) | 9.42 (1.21) | 8.24 (0.26) | 9.60 (0.70) | |

| Seed size (mg) | 2007 | 14.8 (0.3) | 13.8 (0.7) | 14.7 (0.5) | 16.2 (0.6) | 15.1 (0.7) | 17.0 (0.4) | 12.4 (0.5) | 13.1 (0.9) | 13.2 (0.3) |

Data presented are mean ± 1 SE of n = 3 model ecosystems. Non-identical letters (a, b) designate statistically significant differences (P = 0.05, Tukey–Kramer HSD) among maternal CO2 treatments (Case 1; shoot biomass, number of fruits per individual plant, 2005) or combinations of maternal CO2 and plant type (Case 2; seed size of mother plants).

Table 3.

Probability (P) values from mixed-model ANOVA of the size of seeds developed on mother plants and of performance of offspring.

| Variable | Exp. year | Case 1 | Case 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal CO2 | Maternal CO2 | Plant type | Maternal CO2 × Plant type | ||

| MOTHER PLANTS | |||||

| Seed size | Pre-exp. | 0.131 | 0.282 | 0.004 | 0.031 |

| OFFSPRING | |||||

| Seedling emergence | 2006 | 0.880 | 0.698 | 0.046 | 0.696 |

| 2007 | 0.159 | 0.353 | 0.020 | 0.242 | |

| Anthesis | 2006 | 0.499 | 0.562 | 0.023 | 0.796 |

| 2007 | 0.988 | 0.935 | 0.149 | 0.809 | |

| Shoot biomass | 2005 | 0.017 | 0.146 | 0.003 | 0.992 |

| 2006 | 0.810 | 0.662 | <0.001 | 0.948 | |

| Number of fruits per individual plant | 2005 | 0.039 | 0.051 | 0.839 | 0.182 |

| 2006 | 0.815 | 0.780 | 0.003 | 0.422 | |

| 2007 | 0.869 | 0.965 | 0.087 | 0.484 | |

| Number of seeds per individual plant Seed size | 2006 | 0.691 | 0.646 | <0.001 | 0.467 |

| 2007 | 0.867 | 0.845 | 0.309 | 0.221 | |

| 2007 | 0.487 | 0.439 | <0.001 | 0.224 | |

Mixed models consisted of one-way ANOVA (Case 1) or two-way ANOVA (Case 2), and only fixed effects were presented (for random effects, see Materials and Methods). P values ≤ 0.05 were indicated in bold digits, P values ≤ 0.1 and > 0.05 were underlined.

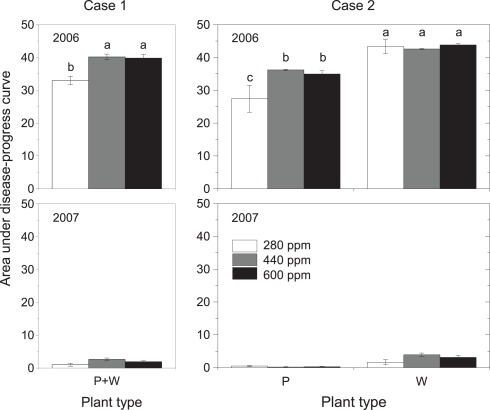

Detailed measurements of disease progress and severity were conducted in 2006 and 2007, a heavy-infection year with disease incidence of 100% and a low-infection year with disease incidence of 81%, respectively. Twelve days after disease onset in 2006 (59 days after sowing, DAS), disease severity was 40% higher in high-CO2 compared with low-CO2 progenies (Figure 2, insert; Table 4). Disease severity increased with time, but differences between maternal CO2 treatments were maintained 69 DAS. The AUDPC over 65 days of disease progress was 21% higher in high-CO2 than in low-CO2 progenies (Figure 3; Table 4). In 2007, disease severity was low and was not affected by maternal CO2. Preliminary one-time recording of disease severity in the heavy-infection year 2005 showed no impact of maternal CO2 (Table 4). However, when a set of individuals of unknown plant type (no record of flower color) was added to the Case 1 analysis, disease severity was 24% higher in high-CO2 than in low-CO2 progenies.

Table 4.

Probability (P) values from mixed-model ANOVA of disease severity and area under disease-progress curve (AUDPC) in the experiments of 2006 and 2007.

| Year | Variable | Time (days after sowing) | Case 1 | Case 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal CO2 | Maternal CO2 | Plant type | Maternal CO2 × Plant type | |||

| 2005 | Disease severity | 76 | 0.606z | 0.780 | 0.005 | 0.759 |

| 2006 | Disease onset | 0.560 | 0.897 | 0.067 | 0.714 | |

| Disease severity | 59 | 0.008 | 0.220 | <0.001 | 0.304 | |

| 69 | 0.020 | 0.328 | 0.001 | 0.095 | ||

| AUDPC | 0.007 | 0.411 | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||

| 2007 | Disease severity | 55 | 0.631 | |||

| 63 | 0.413 | 0.755 | 0.001 | 0.081 | ||

| 69 | 0.365 | 0.621 | 0.004 | 0.147 | ||

| 76 | 0.514 | |||||

| AUDPC | 0.457 | 0.894 | 0.001 | 0.201 |

Mixed models consisted of one-way ANOVA (Case 1) or two-way ANOVA (Case 2), and only fixed effects are presented (for random effects, see Materials and Methods). A more complex model with time as additional factor resulted in interactions between time and other factors (data not shown). P values ≤ 0.05 were indicated in bold digits, P values ≤ 0.1 and > 0.05 were underlined. Empty fields and missing time points represent variables which failed to meet the assumptions of ANOVA. zIncluding only individuals with known plant type in Case 1. If individuals of unknown plant type (flower color was not determined) were also included, the ANOVA of disease severity resulted in P < 0.001. In the latter case, disease severity was significantly higher for high-CO2 (440 and 600 ppm maternal CO2) than for low-CO2 progenies (280 ppm maternal CO2; Tukey–Kramer HSD test, P ≤ 0.05).

Figure 3.

Area under disease-progress curve (AUDPC) as affected by maternal CO2 concentration (280, 440, 600 ppm, Case 1; left panels) and maternal CO2 × plant type (P = pink flowering, W = white flowering, Case 2; right panels) in 2006 and 2007. AUDPC was calculated according to Eq. 1. Mean ± 1 SE, n = 3 model ecosystems. Non-identical letters indicate statistically significant differences among maternal CO2 concentrations (left panels) or combinations of maternal CO2 treatments and plant type (right panels) as analyzed by the Tukey–Kramer HSD test (P ≤ 0.05 within mixed models, see Table 4).

Case 2 (distinguishing between plant types)

Case 2 presents results of the current situation where diverging plant types are distinguished within the population. Maternal CO2 as analyzed under the assumptions of Case 2 affected fruit production, and interacted with plant types on seed size and disease severity, but had no effect on offspring biomass and phenology. Fruit production of high-CO2 offspring was lower (marginally significant) than fruit production of low-CO2 offspring across both plant types in 2005 (Table 3). Maternal CO2 had no statistically significant impact on plant performance in 2006 and 2007. Seeds of the pink-flowering plant type (Type P) that matured under high-CO2 (440 and 600 ppm) and all seeds of the white-flowering type (Type W) were smaller by 20% on average than Type P seeds produced under low CO2 (280 ppm; Tables 2 and 3).

Disease severity was 73% higher in high-CO2 progenies than in low-CO2 progenies of plant type P 59 DAS in 2006 (marginally significant interaction; Figure 2; Table 4). Considering the entire period of infection by the pathogen (AUDPC), high-CO2 progenies of Type P were 30% more diseased than low-CO2 progenies of the same plant type (Figure 3; Table 4). Maternal CO2 concentration had no impact on disease progress and severity in offspring of Type W, and did not affect disease onset in any plant type. In 2007, maternal CO2 interacted with plant type for disease severity 63 DAS (marginally significant).

Plant types differed in phenology, biomass, reproductive output, and disease severity. Seedlings of Type P emerged 1 day earlier on average in 2006 and 1.5 days earlier in 2007 compared with seedlings of Type W (Tables 2 and 3). In addition, Type P plants flowered 5 days earlier than plants of Type W in 2006, but not in 2007. Type P plants had 33 and 56% larger shoot biomass than Type W plants in 2005 and 2006, respectively (Tables 2 and 3). Seed size explained only 11% of offspring shoot biomass in 2006 (P < 0.001, r2 = 0.11, n = 119; seed size was not determined in 2005). In 2006, the number of fruits per individual was 50% higher on average in Type P than in Type W plants, while in 2007, Type P plants had 15% less fruits than Type W plants (marginally significant). Total number of seeds per individual was 75% higher on average in Type P than in Type W plants in 2006. Despite lower fruit production in Type P, the amount of seeds per individual was similar in offspring of both plant types in 2007, due to higher seed production per fruit in Type P (data not shown). Seeds of Type P were 23% larger on average than seeds of Type W. Root biomass and root/shoot ratio were not significantly affected by maternal CO2 and plant type (data not shown).

Type P plants were less affected by the disease than Type W plants in all three experimental years (Figures 2 and 3; Table 4). In 2005, the reduction in disease severity in Type P compared with Type W plants amounted to 30% (0.47 vs. 0.61 on average across maternal CO2 treatments, scale between 0 and 1, 76 DAS). Over the entire disease period (AUDPC) in 2006 and 2007, Type P plants were 24 and 86% less affected by the disease than Type W plants. Fungal mats became visible on plants 46–48 DAS in 2006, with disease onset being 1 d earlier in Type P than in Type W plants (marginally significant).

Discussion

This study on the Mediterranean legume O. crista-galli showed that atmospheric CO2-enrichment potentially exerts maternal effects on the next generation's performance and, most notably, also on its susceptibility to natural infection by a fungal pathogen. However, maternal effects on susceptibility to diseases in offspring might differ among plant types within a population. Maternal effects of global change on disease severity in plants have not been shown so far, but they could affect the species’ performance and fitness under future conditions.

Environmental maternal effects have evolutionary consequences when offspring fitness is influenced by the maternal environment (Rossiter, 1996; Galloway and Etterson, 2007; Wolf and Wade, 2009). This study presents some evidence that rising atmospheric CO2 can impair reproductive output and susceptibility to diseases in offspring. The effect of elevated CO2 still needs to be tested when both mother plants and offspring are grown at elevated CO2. However, the consequences of maternal CO2 for progeny may be independent of the CO2 concentration during progeny development, as shown for a majority of temperate legume and grass species (Fordham et al., 1997; Steinger et al., 2000; Edwards et al., 2001; Lau et al., 2008).

Maternal effects and their modification by plant types and growing conditions

Considering Case 1, elevated CO2 imposed on mother plants reduced offspring shoot biomass and reproductive output (number of fruits) compared with low CO2 in 2005. In addition, severity of the fungal disease powdery mildew was higher in high-CO2 than in low-CO2 offspring in the heavy-infection year 2006, and the same results was obtained in 2005, if all individuals were considered. However, maternal effects of elevated CO2 in Case 1 were often modified when plant types were distinguished in Case 2. The effect of maternal CO2 on offspring biomass in 2005 was not significant anymore when the population was divided into two plant types. The seemingly maternal effect in the normal case when no functionally diverging plant types are obvious (Case 1) turned out to be a plant-type effect in Case 2. Changes in statistically significant main effects from maternal CO2 in Case 1 to plant type in Case 2 could be caused by a different distribution of the two plant types among maternal CO2 treatments. However, this was not the case in 2005 where plant types were distributed at almost identical proportions among maternal CO2 treatments (Table 1). In contrast to offspring biomass, lower reproductive output in high-CO2 compared with low-CO2 offspring in 2005 was significant in both Case 1 and Case 2, with no obvious plant-type effect in the latter case. Fruit production is of particular importance for dispersal of O. crista-galli, since the indehiscent, spiny fruit is the dispersal unit of this species. Less fruits in high-CO2 progeny might result in less dispersal and lower colonization potential compared with low-CO2 progeny.

A maternal CO2 effect on disease severity in Case 2 was recorded only in Type P plants. High maternal CO2 increased disease severity above the level obtained for low maternal CO2 in the more resistant plant-type P, but not in the more susceptible plant-type W. Therefore, high-CO2 reduces the relative advantage of Type P over Type W and might impair its fitness through maternal effects.

Additionally, Case 2 revealed CO2 effects on seed size that were not observed in Case 1. The larger size of seeds on Type P plants from low CO2 could have contributed to some of the growth and disease-resistance effects observed on offspring of this combination of CO2 and plant type.

Interannual variation in maternal effects

Maternal effects of elevated CO2 on plant performance were recorded in 2005, but not in the following 2 years. Since seeds were randomly selected from the same stock for each experimental year, it can be assumed that interannual variation in maternal effects were related to environmental factors, not to a biased seed source. On the one hand, interannual variation in climatic conditions might influence maternal effects (Gendloff et al., 1986). On the other hand, growing conditions, such as larger growth compartments which resulted in larger plants in 2005 than in 2006 and 2007 might also influence maternal effects. Regarding disease severity, degree of infection seemed to affect interactions between maternal CO2 and plant type. High maternal CO2 increased disease severity in the more resistant plant type in a heavy-infection year, but had not in a low-infection year. The year 2005 was also characterized by heavy infection by the disease, but measurements of disease severity in that year were rather preliminary, and potential differences in severity among maternal CO2 treatments went undetected.

The study investigated natural infection of seedlings which, on the one hand, is of relevance for pathogenesis under real field conditions. On the other hand, homogenous infection of plants had to be assumed to allow for proper analyses of findings. Studies with controlled infection could provide further information on maternal effects on susceptibility to fungal and other diseases.

Potential mechanisms of maternal CO2 effects

Maternal effects are a mechanism for phenotypic adaptation to environmental variation (Donohue and Schmitt, 1998; Mousseau and Fox, 1998). For example, life history of progenies in a forest understory was largely determined by the environment encountered by mother plants, and maternal effects in this context represented adaptive plasticity that was transmitted to offspring (Galloway and Etterson, 2007). Several potential mechanisms for environmental maternal effects could be discussed regarding the results obtained in this study. Mother plants of Type P that developed at low CO2 could have transmitted traits related to growth and reproduction to the next generation. However, those plant could not transmit traits for disease susceptibility, since the disease was not evident in the original CO2 experiment. Type P seeds that matured on mother plants at high-CO2 were smaller than seeds that matured at low CO2, which could result from a trade-off between total seed production and the investment in each seed at high vs. low CO2. The smaller high-CO2 seeds can give rise to reduced seedling vigor on the one hand, and less investment in defense mechanisms against infection by pathogens on the other hand (Herms and Mattson, 1992). Smaller nitrogen stores, as obvious in high-CO2 O. crista-galli seeds across plant types (Grünzweig and Dumbur, in press), might provide less nitrogen-based defense compounds in seeds and subsequently in young offspring (Glen et al., 1990; Agrawal, 2002). Other mechanisms might involve inherited epigenetic changes affecting interactions between offspring and the abiotic or biotic environment, including pathogens (Bossdorf et al., 2008). Such epigenetic changes might include yet unspecified mechanisms related to plant defense in offspring (Molinier et al., 2006).

No direct transfer of powdery-mildew propagules from the mother plant to seeds is to be expected, since the disease was not apparent on mother plants and the pathogen is not seed-borne. This also excludes the possibility of a selection effect for more disease resistance during development of mother plants. Although atmospheric CO2 enrichment can impose selective pressure on annual C3 plants (Ward and Kelly, 2004), such an effect was not obvious on growth and reproductive traits. Offspring of the 440-ppm treatment were not superior to offspring of the other treatments, despite the fact that this CO2 concentration was closest to ambient CO2 of ∼380 ppm.

Plant types

In many cases, diverging plant types are not obvious when heterogeneous natural populations are randomly sampled. In this study, plant types within this population of O. crista-galli could be distinguished by differences in flower color (Figure 1). It turned out that the two plant types diverged in all measured variables of plant performance and disease severity, at least in some years. Both plant types were part of the same population, and, thus, represent population-level functional diversity. Without a clear phenotypic marker, many studies are necessarily affected by unknown underlying interference by the variability among plant types, unless detailed genetic analyses are carried out.

The modifying effect of dividing the population of O. crista-galli into plant types on maternal CO2 effects derives mainly from the fact that the two plant types diverge in most variables of plant performance and susceptibility to the disease. Mostly, Type P plants were more vigorous than Type W plants, and disease severity in Type P plants was consistently less pronounced than in Type W plants.

This study also provides a potential explanation for the co-existence of the more disease-resistant Type P and the more susceptible Type W at the same site. In both 2006 and 2007, emergence and initial plant growth was accelerated in Type P compared with Type W seedlings. However, a greater number of leaves produced by Type W plants during mid-season of 2007 indicated that vigor of the latter plant type was at least as high as vigor of Type P plants in nearly disease-free years. This might have evolutionary consequences. In a year with a high disease rate (2006), Type P produced more fruits than Type W, but in a year with low disease rates (2007), Type W produced more fruits (marginally significant). The opposed relative success in fruit production between plant types in contrasting years should result in alternate predominance in dispersal success. This fact may also lead to higher mean fitness of the overall population in that location. However, rising atmospheric CO2 might reduce the relative advantage of plant-type P in heavy-infection years as obvious in 2005, which could negatively affect dispersal success in the long term.

Conclusion

Elevated CO2 applied to mother plants potentially affects offspring performance and susceptibility to a fungal pathogen. However, maternal effects differed among years, and, notably, were modified when the plant population was divided into functionally diverging plant types. Environmental maternal effects are a considerable source of variation in offspring trait-expression, and their consequences for population fitness and for interactions with pathogens could be of high significance for global-change impacts on plant communities.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Jaacov Katan, Robert Kenneth, and Maggie Levy for help with the phytopathological analyses and assistance with the identification of the pathogen, to Shai Morin for help with statistical analyses, and to Baruch Rubin for providing space in the net-house facility. Many thanks to Eyal Fridman, Jaacov Katan, Jaime Kigel, Maggie Levy, and Shmuel Wolf for helpful discussions and comments to an earlier version of the manuscript. The technical assistance of Hadas Sibony, Rita Dumbur, Ahuva Nir, Gil Yogev, Ziv Kleinman, Aia Oz, and Shirly Dafni is greatly acknowledged.

References

- Agrawal A. A. (2002). Herbivory and maternal effects: Mechanisms and consequences of transgenerational induced plant resistance. Ecology 83, 3408–3415 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[3408:HAMEMA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amano K. (1986). Host Range and Geographical Distribution of the Powdery Mildew Fungi. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Scientific Societies Press [Google Scholar]

- Andalo C., Godelle B., Lefranc M., Mousseau M., Till-Bottraud I. (1996). Elevated CO2 decreases seed germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2, 129–135 10.1111/j.1365-2486.1996.tb00057.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah T., Rizk H., Cherfane A., Daher F. B., El-Alia R., De Lajuide P., Hajj S. (2008). Distribution and nodulation of spontaneous legume species in grasslands and shrublands in Mediterranean Lebanon. Arid Land Res. Manag. 22, 109–122 10.1080/15324980801957978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augspurger C. K. (1983). Seed dispersal of the tropical tree Platypodium elegans, and the escape of its seedlings from fungal pathogens. J. Ecol. 71, 759–771 10.2307/2259591 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossdorf O., Richards C. L., Pigliucci M. (2008). Epigenetics for ecologists. Ecol. Lett. 11, 106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdon J. J., Thrall P. H., Ericson L. (2006). The current and future dynamics of disease in plant communities. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 19–39 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.140238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Tiedemann A. V., Teng P. S. (2000). Climate change: potential impact on plant diseases. Environ. Pollut. 108, 317–326 10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00209-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue K., Schmitt J. (1998). “Maternal environmental effects in plants: adaptive plasticity?,” in Maternal Effects as Adaptations, eds Mousseau T. A., Fox C. W. (New York: Oxford University Press; ), 137–158 [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G. R., Newton P. C. D., Tilbrook J. C., Clark H. (2001). Seedling performance of pasture species under elevated CO2. New Phytol. 150, 359–369 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00100.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman T., Cocks P. S. (1996). Reproductive patterns in annual legume species on an aridity gradient. Vegetatio 122, 47–59 10.1007/BF00052815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farnsworth E. J., Bazzaz F. A. (1995). Inter- and intra-generic differences in growth, reproduction, and fitness of nine herbaceous annual species grown in elevated CO2 environments. Oecologia 104, 454–466 10.1007/BF00341343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordham M., Barnes J. D., Bettarini I., Polle A., Slee N., Raines C., Miglietta F., Raschi A. (1997). The impact of elevated CO2 on growth and photosynthesis in Agrostis canina L. ssp. monteluccii adapted to contrasting atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Oecologia 110, 169–178 10.1007/s004420050146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway L. F. (2005). Maternal effects provide phenotypic adaptation to local environmental conditions. New Phytol. 166, 93–99 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01314.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway L. F., Etterson J. R. (2007). Transgenerational plasticity is adaptive in the wild. Science 318, 1134–1136 10.1126/science.1148766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett K. A., Dendy S. P., Frank E. E., Rouse M. N., Travers S. E. (2006). Climate change effects on plant disease: genomes to ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 489–509 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendloff E. H., Rossman E. C., Casale W. L., Isleib T. G., Hart L. P. (1986). Components of resistance to Fusarium ear rot in field corn. Phytopathology 76, 684–688 10.1094/Phyto-76-684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glen D. M., Jones H., Fieldsend J. K. (1990). Damage to oilseed rape seedlings by the field slug Deroceras reticulatum in relation to glucosinolate concentration. Ann. Appl. Biol. 117, 197–207 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1990.tb04835.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grünzweig J. M., Dumbur R. (in press). Seed traits, seed-reserve utilization and offspring performance across pre-industrial to future CO2 concentrations in a Mediterranean community. Oikos. [Google Scholar]

- Grünzweig J. M., Körner C. (2000). Growth and reproductive responses to elevated CO2 in wild cereals of the northern Negev of Israel. Glob. Chang. Biol. 6, 231–238 [Google Scholar]

- Grünzweig J. M., Körner C. (2001a). Biodiversity effects of elevated CO2 in species-rich model communities from the semi-arid Negev of Israel. Oikos 95, 112–124 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.950113.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grünzweig J. M., Körner C. (2001b). Growth, water and nitrogen relations in grassland model ecosystems of the semi-arid Negev of Israel exposed to elevated CO2. Oecologia 128, 251–262 10.1007/s004420100657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hely F. W., Ofer I. (1972). Nodulation and frequencies of wild leguminous species in the northern Negev region of Israel. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 23, 267–284 10.1071/AR9720267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herms D. A., Mattson W. J. (1992). The dilemma of plants: to grow or defend. Q. Rev. Biol. 67, 283–335 10.1086/417659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn C. C. (1962). On the cytotaxonomy of Onobrychis crista-galli (L.) Lam. and O. squarrosa Viv. Bull. Res. Coun. Isr. 11D, 177–182 [Google Scholar]

- Hovenden M. J., Wills K. E., Chaplin R. E., Van Der Schoor J. K., Williams A. L., Osanai Y., Newton P. C. D. (2008). Warming and elevated CO2 affect the relationship between seed mass, germinability and seedling growth in Austrodanthonia caespitosa, a dominant Australian grass. Glob. Chang. Biol. 14, 1633–1641 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01558.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huxman T. E., Hamerlynck E. P., Jordan D. N., Salsman K. J., Smith S. D. (1998). The effects of parental CO2 environment on seed quality and subsequent seedling performance in Bromus rubens. Oecologia 114, 202–208 10.1007/s004420050437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. (2007). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Karaboz I., öner M. (1982). Parasitic fungi from the province of Manisa. Mycopathologia 79, 129–131 10.1007/BF01837190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C. (2006). Plant CO2 responses: an issue of definition, time and resource supply. New Phytol. 172, 393–411 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01886.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J. A., Peiffer J., Reich P. B., Tiffin P. (2008). Transgenerational effects of global environmental change: long-term CO2 and nitrogen treatments influence offspring growth response to elevated CO2. Oecologia 158, 141–150 10.1007/s00442-008-1127-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J. A., Shaw R. G., Reich P. B., Shaw F. H., Tiffin P. (2007). Strong ecological but weak evolutionary effects of elevated CO2 on a recombinant inbred population of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 175, 351–362 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunsford J. N., Futrell M. C., Scott G. E. (1976). Maternal effects and type of gene action conditioning resistance to Fusarium moniliforme seedling blight in maize. Crop Sci. 16, 105–107 10.2135/cropsci1976.0011183X001600010027x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mcelrone A. J., Reid C. D., Hoye K. A., Hart E., Jackson R. B. (2005). Elevated CO2 reduces disease incidence and severity of a red maple fungal pathogen via changes in host physiology and leaf chemistry. Glob. Chang. Biol. 11, 1828–1836 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001015.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C. E., Reich P. B., Tilman D., Groth J. V. (2003). Effects of elevated CO2, nitrogen deposition, and decreased species diversity on foliar fungal plant disease. Glob. Chang. Biol. 9, 438–451 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00602.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molinier J., Ries G., Zipfel C., Hohn B. (2006). Transgeneration memory of stress in plants. Nature 442, 1046–1049 10.1038/nature05022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau T. A., Fox C. W. (1998). The adaptive significance of maternal effects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 403–407 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01472-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühle E., Frauenstein K. (1970). Contribution to the occurrence of powdery mildew of red clover and sainfoin. J. Phytopathol. 69, 9–16 [in German]. 10.1111/j.1439-0434.1970.tb03895.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plessl M., Elstner E. F., Rennenberg H., Habermeyer J., Heiser I. (2007). Influence of elevated CO2 and ozone concentrations on late blight resistance and growth of potato plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 60, 447–457 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rayss T. (1940). Nouvelle contribution a l'étude de la mycoflore de Palestine. Palestine J. Bot. 1, 313–335 [in French]. [Google Scholar]

- Roach D. A., Wulff R. D. (1987). Maternal effects in plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 18, 209–235 [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter M. C. (1996). Incidence and consequences of inherited environmental effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 27, 451–476 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.451 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner G., Finney R. E. (1977). The effect of nitrogen fertilization on the expression of slow-mildewing resistance in Knox wheat. Phytopathology 67, 1051–1056 10.1094/Phyto-67-1051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinger T., Gall R., Schmid B. (2000). Maternal and direct effects of elevated CO2 on seed provisioning, germination and seedling growth in Bromus erectus. Oecologia 123, 475–480 10.1007/s004420000342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thürig B., Körner C., Stöcklin J. (2003). Seed production and seed quality in a calcareous grassland in elevated CO2. Glob. Chang. Biol. 9, 873–884 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00581.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. K., Kelly J. K. (2004). Scaling up evolutionary responses to elevated CO2: lessons from Arabidopsis. Ecol. Lett. 7, 427–440 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00589.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J. B., Wade M. J. (2009). What are maternal effects (and what are they not)? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 1107–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulff R. D. (1995). “Environmental maternal effects on seed quality and germination,” in Seed Development and Germination, eds Kigel J., Galili G. (New York: Marcel Dekker; ), 491–504 [Google Scholar]