Abstract

Plant cell walls are composed of interlinked polymer networks consisting of cellulose, hemicelluloses, pectins, proteins, and lignin. The ordered deposition of these components is a dynamic process that critically affects the development and differentiation of plant cells. However, our understanding of cell wall synthesis and remodeling, as well as the diverse cell wall architectures that result from these processes, has been limited by a lack of suitable chemical probes that are compatible with live-cell imaging. In this review, we summarize the currently available molecular toolbox of probes for cell wall polysaccharide imaging in plants, with particular emphasis on recent advances in small molecule-based fluorescent probes. We also discuss the potential for further development of small molecule probes for the analysis of cell wall architecture and dynamics.

Keywords: plant cell wall, cell wall dynamics, cellulose, pectin, click chemistry

Introduction

Terrestrial plants annually assimilate 1.3 × 1011 metric tons of CO2 through the process of photosynthesis (Beer et al., 2010), and the majority of the resulting photosynthate is used to produce the polysaccharide-rich walls that surround plant cells (Pauly and Keegstra, 2008). These complex extracellular matrices are composed of cellulose microfibrils (CMFs), neutral hemicelluloses, acidic pectins, and proteins and must simultaneously be strong enough to resist the substantial cellular osmotic pressure necessary to support turgor-mediated cell growth and dynamic enough to allow cell expansion to occur (Somerville et al., 2004; Cosgrove, 2005). As a result, the ordered deposition of plant cell walls determines the patterning and extent of plant growth and development at the cellular level (Desnos et al., 1996; Arioli et al., 1998; Nicol et al., 1998).

Despite the physiological importance of cell wall deposition and dynamics, relatively little is known about cell wall structure in living cells, primarily due to a paucity of effective labeling strategies for polysaccharides in their native environment. Genetically encoded fluorescent tags for polysaccharides do not exist, necessitating novel approaches for the specific labeling of cell wall glycans. Although chemical (Reiter et al., 1997; Brown et al., 2007) and biochemical (Lerouxel et al., 2002; Barton et al., 2006; Bauer et al., 2006) techniques can accurately determine the primary structures of polysaccharides, these methods provide few spatial details due to the necessity for sample homogenization. Imaging approaches, such as transmission electron microscopy (Moore et al., 1991; Lynch and Staehelin, 1992), Raman microspectroscopy (Schmidt et al., 2010), and fluorescence microscopy with an array of polysaccharide-specific antibodies, lectins, and carbohydrate binding domains (Pattathil et al., 2010) have provided qualitative information regarding the localization and relative abundance of numerous cell wall polysaccharides. However, these techniques are limited by long sample preparation times, potential fixation artifacts, loss of temporal information, lack of epitope specificity (Pattathil et al., 2010), and complications in interpretation due to epitope masking (Marcus et al., 2008). In addition, protein-based probes, particularly intact 160 kDa IgG molecules, are very large compared to the approximately 3 nm pore size of cell walls (Chesson et al., 1997) and may not efficiently label some cell wall components (Marcus et al., 2010). As a result, many developmental changes in cell wall architecture cannot be fully characterized using these approaches.

Polysaccharide-specific fluorescent probes and metabolic labels augment the currently available cell wall imaging toolbox, with the added benefit that these probes are compatible with live-cell imaging and/or pulse-chase experiments. In this review, we summarize the recent development of specific small molecule chemical probes for cell wall imaging, and the insights that these new probes have provided concerning plant cell wall structure.

Cell Wall Polysaccharide Biosynthesis

The structural complexity of the plant cell wall arises in part due to the variety of polysaccharides used to assemble this organelle, the spatial and temporal separation of their synthesis, and the various chemical modifications that occur within these polysaccharides. Cell wall polysaccharides are often grouped into three functional categories: cellulose, hemicelluloses, and pectins. Cellulose is composed of 30–40 β-(1 → 4)-linked glucan chains that associate to produce semi-crystalline CMFs (Somerville, 2006). These structural polysaccharides are synthesized at the plasma membrane by 30 nm “rosette” complexes (Arioli et al., 1998; Kimura et al., 1999) containing multiple cellulose synthase A (CesA) catalytic subunits (Taylor et al., 2003; Desprez et al., 2007; Persson et al., 2007). Live-cell imaging has indicated that CesA-containing complexes co-align with cortical microtubules underlying the plasma membrane as they produce nascent CMFs (Paredez et al., 2006; Li et al., 2012), which are deposited in the apoplast.

In contrast to CMFs, hemicelluloses and pectins are synthesized in the Golgi (Mohnen, 2008; Caffall and Mohnen, 2009) and delivered to the apoplast by vesicle-mediated exocytosis via an incompletely described pathway (Moore et al., 1991; Lynch and Staehelin, 1992). Once deposited in the apoplast, hemicelluloses, such as xyloglucan, are thought to associate with and crosslink CMFs in the cell wall (Vincken et al., 1995; Lima et al., 2004), forming a cellulose–hemicellulose network. The interaction between these polysaccharides is proposed to prevent individual CMFs from interacting with each other and to help organize CMFs into a cohesive, dynamic network, although this model has recently been challenged (Park and Cosgrove, 2012b). Hemicelluloses and CMFs are embedded in a gel-like matrix composed of the pectic polysaccharides homogalacturonan, xylogalacturonan (XGA), rhamnogalacturonan-I (RG-I), and rhamnogalacturonan-II (RG-II) which together control aspects of cell adhesion, wall extensibility, and wall porosity (Krupkova et al., 2007; Mohnen, 2008).

Plant cell wall polysaccharides can also be modified during synthesis or after deposition in the apoplast by the activity of various enzymes. Pectins can be reversibly acetylated at the O-2 or O-3 hydroxyl groups of their galacturonic acid backbone sugars and/or methylesterified at the O-6 carboxyl group (Ishii, 1997; Manabe et al., 2011). Hemicelluloses can also be acetylated (Pauly et al., 1999; Kabel et al., 2003; Gibeaut et al., 2005; Gille et al., 2011) or have their glycan side chains modified during plant development (Günl et al., 2011). Finally, transglycosylase enzymes, such as xyloglucan endotransglycosylase (XET), cut and religate individual xyloglucan chains during wall extension (Xu et al., 1995; Maris et al., 2009). These modifications can significantly affect the physical properties of individual wall polymers (Huang et al., 2002; Ngouemazong et al., 2012) and of the cell wall as a whole (Krupkova et al., 2007; Peaucelle et al., 2008).

Polysaccharide-Binding Dyes and Metabolic Labels for Cell Wall Polysaccharide Imaging

Cell wall polysaccharides are structurally diverse, exist in complex three-dimensional arrangements, and are synthesized, deposited, modified, and degraded in highly dynamic processes. Therefore, probes that are highly specific for an individual polysaccharide type and compatible with live-cell imaging can effectively capture this complexity. Various polysaccharide-binding dyes, including Calcofluor white (Fagard et al., 2000; Homann et al., 2007; Harpaz-Saad et al., 2011), Congo red (Kerstens and Verbelen, 2002), ruthenium red (Western et al., 2001; Marks et al., 2008; Harpaz-Saad et al., 2011), and Aniline blue (Adam and Somerville, 1996; Nishikawa et al., 2005; Nguyen et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2011), have been used as imaging tools for plant cell walls, but these dyes cross-react with multiple polysaccharides, and their direct glycan targets are often unknown. To address this issue, Anderson et al. (2010) assayed the previously described fungal cell wall-binding dyes Pontamine Fast Scarlet S4B (S4B) and Solophenyl Flavine 7GFE (7GFE; Hoch et al., 2005) for their ability to bind isolated cell wall polysaccharides. S4B (Figure 1A) exhibits several useful imaging properties, including increased fluorescence intensity in the presence of cellulose, increased glycan specificity over Calcofluor white, and spectral properties compatible with 532 and 561 nm lasers. S4B is also non-toxic at concentrations that are compatible with fluorescent imaging and can thus be used as a specific probe to dynamically image cellulose in living plant tissues. 7GFE (Figure 1B) exhibits a characteristic shift in its fluorescence emission maximum in the presence of xyloglucan, but not cellulose. Whereas 7GFE is slightly more toxic than S4B, this dye could potentially serve as an orthogonal fluorescent label for xyloglucan because its excitation and emission maxima do not overlap with those of S4B (Anderson et al., 2010).

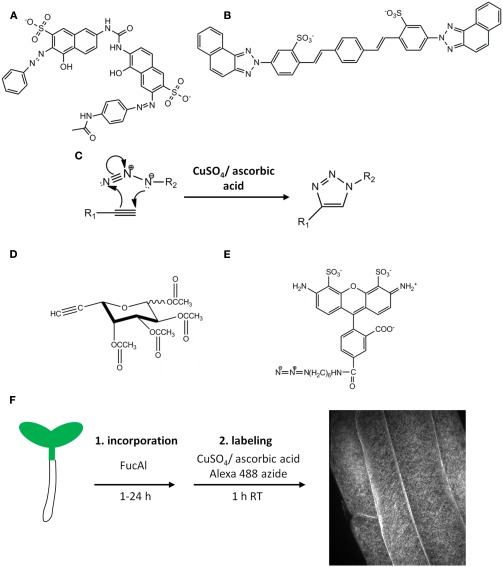

Figure 1.

Fluorescent probes for cell wall polysaccharide imaging. The structures of the cellulose-binding dye Pontamine Fast Scarlet 4B (S4B) (A) and the xyloglucan-binding dye Solophenyl Flavine 7GFE (B). (C) A generalized version of the copper-catalyzed Huisgen [2 + 3] cycloaddition reaction. This reaction is useful for coupling molecules containing terminal alkynyl or azido groups, such as per-acetylated fucose alkyne (FucAl) (D) and Alexa-488 azide (E). Sugar analogs such as FucAl can be metabolically incorporated into glycans via the action of sugar salvage pathways and cognate glycosyltransferases, producing modified polysaccharides that can be labeled with azido-containing fluorophores by the click reaction. This strategy was used in Anderson et al. (2012) to metabolically label pectins by incorporating FucAl into the root tissue of Arabidopsis followed by copper-catalyzed labeling as shown in (F). A representative image of root epidermal cells in the late elongation zone after labeling is shown in the right panel.

S4B, 7GFE, and other fluorescent polysaccharide-binding probes are valuable tools that should be explored further, but the biophysical details of many dye–polysaccharide interactions are currently unknown, preventing the rational design of new dyes. However, alternative labeling strategies can be employed to design metabolic probes that can be targeted to individual cell wall polysaccharide networks. For example, fluorescently labeled xyloglucan fragments are metabolically incorporated into subdomains of xyloglucan by XETs, and these oligosaccharides have been used to image the sites of XET activity during cell expansion (Vissenberg et al., 2000). Additionally, molecules containing terminal alkynyl or azido functional groups can participate in a copper-catalyzed [2 + 3] cycloaddition referred to as the Huisgen “click” reaction (Figure 1C), which is bio-orthogonal, proceeds rapidly at room temperature with high specificity, and results in the formation of a stable triazole ring (Kolb et al., 2001; Rostovtsev et al., 2002; Tornoe et al., 2002). Exploiting this reaction, small, biologically relevant molecules containing these functional groups have been synthesized and incorporated into proteins, fatty acids, nucleic acids, and sugars which are then covalently labeled with useful probes, such as fluorophores, epitope tags, or other affinity reagents that contain the opposite functional group (Chin et al., 2002; Kiick et al., 2002; Deiters et al., 2003; Kho et al., 2004; Link et al., 2006; Rabuka et al., 2006; Hang et al., 2007; Hsu et al., 2007; Jao and Salic, 2008; Salic and Mitchison, 2008; Chang et al., 2009; Kaschani et al., 2009). These chemical methods have been particularly useful for imaging glycan conjugates in animal, bacterial, and fungal systems (Prescher et al., 2004; Dube et al., 2006; Laughlin et al., 2008), but had not previously been explored in the context of the plant cell wall.

Anderson et al. (2012) investigated the potential of click chemistry to label cell wall polysaccharides using per-acetylated fucose alkyne (FucAl; Figure 1D) as a suitable click sugar monosaccharide analog. FucAl was metabolically incorporated into Arabidopsis root tissue and labeled with Alexa-488 azide using the copper-catalyzed click reaction (Figures 1D–F). Cytological and biochemical analyses indicated that the majority of the FucAl label was incorporated into the pectic fraction of Arabidopsis cell walls, most likely in arabinogalactan side chains of rhamnogalacturonan-I (RG-I). Fucose is present in multiple cell wall polysaccharides (Nakamura et al., 2001; Lerouxel et al., 2002; Glushka et al., 2003; Strasser et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2010), but Arabidopsis mutants lacking fucosyltransferases for xyloglucan (Vanzin et al., 2002), arabinogalactan protein (Wu et al., 2010), and N-linked glycoproteins (Strasser et al., 2004) incorporated FucAl at levels similar to wild-type plants, suggesting that FucAl does not evenly label all fucosylated cell wall glycans (Anderson et al., 2012). We hypothesize that this selectivity might arise from conformational differences in the active sites of different fucosyltransferases, suggesting that click chemistry-compatible sugar analogs might be selectively incorporated into specific polysaccharide networks even if the parent monosaccharide is present in several polymers. Structure–activity relationships of click sugar variants containing the alkyne or azide at different positions may elucidate the structural requirements for selective monosaccharide analog incorporation.

Polysaccharide Imaging Probes Highlight the Structural Dynamics of Cell Walls During Development

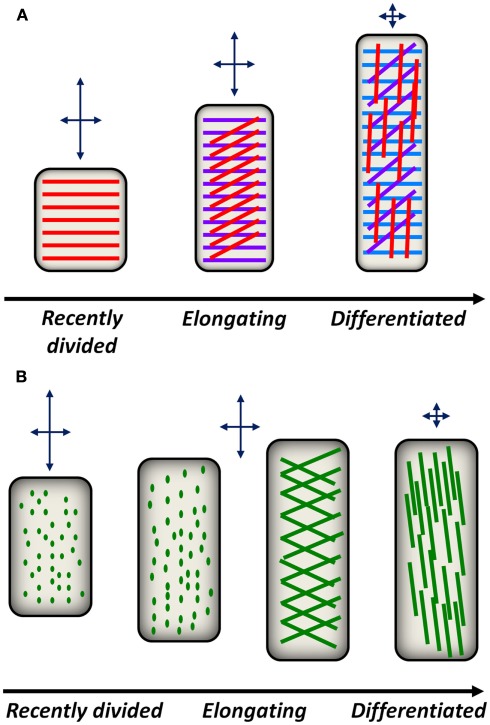

S4B staining and spinning disk confocal microscopy were used to image CMFs in Arabidopsis root tissues (Anderson et al., 2010), which represent a developmental continuum of dividing, expanding, and differentiated cells (Dolan et al., 1993). S4B-stained CMFs were transversely oriented with respect to the major cellular expansion axis in recently divided cells near the root cap and cells in the early elongation zone. However, older cells in the elongation zone exhibited diagonally oriented CMFs, and fully differentiated cells that were no longer expanding contained longitudinally oriented CMFs (Figure 2A). This developmental gradient of CMF orientation agrees with previous electron microscopy studies describing developmental changes in CMF orientation along Arabidopsis roots and hypocotyls (Sugimoto et al., 2000; Refregier et al., 2004), suggesting that S4B staining provides a rapid and specific method for CMF imaging.

Figure 2.

Conceptual models for cell wall polysaccharide deposition and reorientation during plant development. (A) A model for cellulose deposition and reorientation in anisotropically elongating root epidermal cells. Shortly after division in the root meristematic region, cellulose synthase complexes in epidermal cells deposit cellulose (red lines) in a transverse orientation with respect to the elongation axis. This deposition pattern constrains radial expansion of the cell but permits axial expansion as indicated by the arrows above each cell. As epidermal cells elongate, new cellulose layers (magenta lines, blue lines) are deposited transversely, while older layers in the apoplast passively reorient from transverse to diagonal, then longitudinal orientations. The reorientation of older cellulose layers reduces the ability of differentiating cells to expand in the axial direction. (B) A model for pectin deposition and remodeling in the apoplast. In recently divided cells, pectic polysaccharides are delivered to the apoplast by secretory vesicles. Putative sites of pectin delivery (green dots) can be imaged with FucAl and are initially distributed evenly across the cell. As epidermal cells stop elongating, diagonal fibrils begin to appear that eventually reorient toward the longitudinal axis, potentially constraining further axial expansion.

FucAl incorporation and labeling has been used to image pectic networks along the same root developmental continuum. After 1 h of incorporation, FucAl labeling in the root elongation zone appeared as small puncta in the cell wall (Anderson et al., 2012), potentially representing the locations of vesicle-mediated pectin delivery to the apoplast. After longer incorporation times (e.g., 12 h), the pattern of FucAl labeling in Arabidopsis roots exhibited a developmental gradient from the early elongation zone to the differentiation zone. In recently divided cells, FucAl-associated fluorescence was homogeneous, likely as a result of cumulative evenly distributed vesicle-mediated polysaccharide delivery. However, cells in the late elongation zone exhibit more organized patterns of puncta that transition to diagonally oriented fibrillar structures in the differentiation zone (Anderson et al., 2012). These observations suggest that pectic wall material is delivered and organized in distinct patterns during cellular development and that this developmental gradient parallels the reorientation of CMFs during cell elongation (Figure 2B).

Polysaccharide-specific probes can also serve as useful tools for the detailed characterization of mutants affecting cell wall polymer networks. For example, S4B staining has revealed new aspects of wall morphology in previously described Arabidopsis mutants defective in cellulose and xyloglucan biosynthesis. The CesA6 mutant Procuste1-1 (prc1-1; Desnos et al., 1996) produces less crystalline cellulose in its cell walls (Fagard et al., 2000), and prc1-1 seedlings exhibited reduced S4B staining compared to wild-type seedlings (Anderson et al., 2010). Additionally, microfibrils in the root elongation zone were more defined but less prevalent, suggesting that fewer intact microfibrils were synthesized, leading to compromised cell walls and increased isotropic expansion of root cells. S4B staining of the xxt1; xxt2 mutant, which lacks detectable amounts of xyloglucan (Cavalier et al., 2008; Park and Cosgrove, 2012a), labeled CMF fibers that were more prominently defined and thicker than wild-type CMF fibers, supporting the hypothesis that hemicelluloses prevent CMFs from interacting with each other in wild-type primary cell walls. Furthermore, S4B was recently used to characterize cellulose architecture in Arabidopsis seed coat mucilage (Harpaz-Saad et al., 2011), leading to the identification of Cellulose Synthase A5 (CesA5), FEI2, and Salt Overly Sensitive 5 (SOS5) as genes responsible for mucilage cellulose deposition. This study indicates that fluorescent probes like S4B will be useful for cell wall imaging and mutant phenotype identification in multiple developmental contexts.

Dynamic Reorientation of Cell Wall Polysaccharide Networks

Due to the load-bearing function of CMFs in the cell wall, differences in the orientation of these polymers with respect to the growth axis of anisotropically expanding cells has been proposed to critically affect cell shape (Green, 1960). When CMFs are deposited transversely, they resist radial expansion but allow cells to expand axially. However, as CMFs become longitudinally oriented and parallel to the elongation axis, cells are also expected to encounter expansion resistance in the axial direction (Figure 2A). Previous observations suggest that varying CMF angles may result from reorientation of these polysaccharides after deposition in the apoplast (Refregier et al., 2004). Optical sectioning of S4B-stained tissue indicates that CMFs in the outer cell wall layers of differentiated root epidermal cells are oriented longitudinally with respect to the cellular growth axis, whereas CMFs near the inner face of the wall are oriented transversely (Anderson et al., 2010). Time-lapse imaging of S4B-stained CMFs revealed that the observed changes in orientation are attributable to the rotation of CMFs after they are deposited in the apoplast of root epidermal cells.

FucAl incorporation and labeling was also used to examine the dynamics of pectic networks in Arabidopsis (Anderson et al., 2012). Whereas the amounts of FucAl required for incorporation experiments had no effect on normal Arabidopsis seedling development, the Cu (I) necessary to catalyze the cycloaddition reaction was toxic, in agreement with previous in vitro and in vivo observations in other organisms (Agard et al., 2004; Brewer, 2010; Lallana et al., 2011). As an alternative to in vivo imaging, plants were pulsed with FucAl for 1 h and labeled at various chase times (Anderson et al., 2012). These experiments revealed that FucAl-associated fluorescence was initially punctate in the apoplast, but appeared as longitudinal fibers after 12 or 24 h chase periods, suggesting that, like CMFs, pectins become longitudinally oriented over time. As a whole, these observations suggest that polysaccharide networks are highly dynamic during cellular development and highlight the importance of specific polysaccharide-directed probes that are capable of capturing these events.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The use of multiple labeling strategies for plant cell wall polysaccharides is altering the perception of the cell wall from that of a rigid case to that of a highly dynamic extracellular organelle that changes during development. However, the complexity of the cell wall necessitates the design of specific imaging probes for these dynamic events. Polysaccharide-binding dyes, such as S4B and 7GFE, highlight the utility of fluorescent dyes that are compatible with live-cell imaging and exemplify one avenue for the implementation of new cell wall imaging tools for the future. Indeed, we believe that novel cell wall imaging probes will most likely be isolated via high-throughput fluorescent interaction assays against isolated wall components, structure–activity studies of existing fluorophores, or array-based selectivity analyses that have been described for polysaccharide-binding antibodies (Moller et al., 2008; Pattathil et al., 2010; Sorensen and Willats, 2011). These experiments may lead to the identification of novel fluorophores that label unique polysaccharide populations or networks, so that multiple cell wall polysaccharides can be imaged simultaneously.

Monosaccharide analogs compatible with click chemistry have some advantages over polysaccharide-specific fluorophores that suggest their utility in a variety of experiments. Because click sugars are incorporated metabolically, they label only those polysaccharides synthesized during the incorporation period and are therefore distinct from probes that label all of the existing polysaccharides of a given type. These sugars have the potential to serve as valuable tools for examining the trafficking of polysaccharides from the Golgi to the apoplast, elucidating extracellular events that occur after deposition of polysaccharides in the wall, and the isolation of mutants that affect these processes. These experimental goals will be furthered by the application of click sugars that label other polysaccharide networks, and it may be possible to tune the selective incorporation of a given sugar analog by changing the position or identity of the alkynyl or azido functional group. Membrane permeable click-compatible coumarin and napthalamide fluorescent probes have been described (Sawa et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2007), and could be used to image intracellular sites of polysaccharide synthesis to complement surface-specific labeling by membrane impermeable fluorophores, such as Alexa Fluor dyes. Additionally, in vivo click labeling using either copper-free strain-promoted [2 + 3] cycloaddition reactions (Prescher et al., 2004; Dube et al., 2006; Laughlin et al., 2008) or chelators that sequester toxic Cu (I) (Chan et al., 2004; Lewis et al., 2004) might be applicable to plant systems and could further facilitate the imaging of cell wall glycans in living cells. By adding a temporal dimension to studies of cell wall architecture, the approaches described here provide new ways of examining the synthesis, deposition, and dynamics of plant cell walls that will further our understanding of these remarkable bio-materials, both in the context of plant development and as renewable resources for human use.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a US Department of Energy grant DOE-FG02-03ER20133 awarded to Chris Somerville. In addition, the contributions of C.T.A. to this work were supported as part of The Center for LignoCellulose Structure and Formation, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Award Number DE-SC0001090.

References

- Adam L., Somerville S. C. (1996). Genetic characterization of five powdery mildew disease resistance loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 9, 341–356 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.09030341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agard N. J., Prescher J. A., Bertozzi C. R. (2004). A strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition for covalent modification of biomolecules in living systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 15046–15047 10.1021/ja044996f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. T., Carroll A., Akhmetova L., Somerville C. (2010). Real-time imaging of cellulose reorientation during cell wall expansion in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 152, 787–796 10.1104/pp.109.150128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. T., Wallace I. S., Somerville C. R. (2012). Metabolic click-labeling with a fucose analog reveals pectin delivery, architecture, and dynamics in Arabidopsis cell walls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1329–1334 10.1073/pnas.1120429109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arioli T., Peng L., Betzner A. S., Burn J., Wittke W., Herth W., Camilleri C., Hofte H., Plazinski J., Birch R., Cork A., Glover J., Redmond J., Williamson R. E. (1998). Molecular analysis of cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Science 279, 717–720 10.1126/science.279.5351.717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton C. J., Tailford L. E., Welchman H., Zhang Z., Gilbert H. J., Dupree P., Goubet F. (2006). Enzymatic fingerprinting of Arabidopsis pectic polysaccharides using polysaccharide analysis by carbohydrate electrophoresis (PACE). Planta 224, 163–174 10.1007/s00425-005-0185-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S., Vasu P., Persson S., Mort A. J., Somerville C. R. (2006). Development and application of a suite of polysaccharide-degrading enzymes for analyzing plant cell walls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11417–11422 10.1073/pnas.0603625103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer C., Reichstein M., Tomelleri E., Ciais P., Jung M., Carvalhais N., Rodenbeck C., Arain M. A., Baldocchi D., Bonan G. B., Bondeau A., Cescatti A., Lasslop G., Lindroth A., Lomas M., Luyssaert S., Margolis H., Oleson K. W., Roupsard O., Veenendaal E., Viovy N., Williams C., Woodward F. I., Papale D. (2010). Terrestrial gross carbon dioxide uptake: global distribution and covariation with climate. Science 329, 834–838 10.1126/science.1184984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. J. (2010). Risks of copper and iron toxicity during aging in humans. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 23, 319–326 10.1021/tx900338d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. M., Goubet F., Wong V. W., Goodacre R., Stephens E., Dupree P., Turner S. R. (2007). Comparison of five xylan synthesis mutants reveals new insight into the mechanism of xylan synthesis. Plant J. 52, 1154–1168 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffall K. H., Mohnen D. (2009). The structure, function, and biosynthesis of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 344, 1879–1900 10.1016/j.carres.2009.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier D. M., Lerouxel O., Neumetzler L., Yamauchi K., Reinecke A., Freshour G., Zabotina O. A., Hahn M. G., Burgert I., Pauly M., Raikhel N. V., Keegstra K. (2008). Disrupting two Arabidopsis thaliana xylosyltransferase genes results in plants deficient in xyloglucan, a major primary cell wall component. Plant Cell 20, 1519–1537 10.1105/tpc.108.059873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan T. R., Hilgraf R., Sharpless K. B., Fokin V. V. (2004). Polytriazoles as copper(I)-stabilizing ligands in catalysis. Org. Lett. 6, 2853–2855 10.1021/ol0492952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P. V., Chen X., Smyrniotis C., Xenakis A., Hu T., Bertozzi C. R., Wu P. (2009). Metabolic labeling of sialic acids in living animals with alkynyl sugars. Agnew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 4030–4033 10.1002/anie.200806319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesson A., Gardener P. T., Wood T. J. (1997). Cell wall porosity and available surface area of wheat straw and wheat grain fractions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 75, 289–295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J. W., Santoro S. W., Martin A. B., King D. S., Wang L., Schultz P. G. (2002). Addition of p-azido-L-phenylalanine to the genetic code of Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 9026–9027 10.1021/ja012312n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (2005). Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 850–861 10.1038/nrm1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiters A., Cropp T. A., Mukherji M., Chin J. W., Anderson J. C., Schultz P. G. (2003). Adding amino acids with novel reactivity to the genetic code of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 11782–11783 10.1021/ja0370037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnos T., Orbovic V., Bellini C., Kronenberger J., Caboche M., Traas J., Hofte H. (1996). Procuste 1 mutants identify two distinct genetic pathways controlling hypocotyl cell elongation respectively in dark- and light-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. Development 122, 683–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desprez T., Juraniec M., Crowell E. F., Jouy H., Pochylova Z., Parcy F., Hofte H., Gonneau M., Vernhettes S. (2007). Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15572–15577 10.1073/pnas.0706569104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan L., Janmaat K., Willemsen V., Linstead P., Poethig S., Roberts K., Scheres B. (1993). Cellular organization of the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Development 119, 71–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube D. H., Prescher J. A., Quang C. N., Bertozzi C. R. (2006). Probing mucin-type O-linked glycosylation in living animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4819–4824 10.1073/pnas.0506855103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard M., Desnos T., Desprez T., Goubet F., Refregier G., Mouille G., McCann M., Rayon C., Vernhettes S., Hofte H. (2000). PROCUSTE1 encodes a cellulose synthase required for normal cell elongation specifically in roots and dark-grown hypocotyls of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12, 2409–2424 10.2307/3871238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut D. M., Pauly M., Bacic A., Fincher G. B. (2005). Changes in cell wall polysaccharides in developing barley (Hordeum vulgare) coleoptiles. Planta 221, 729–738 10.1007/s00425-005-1481-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille S., de Souza A., Xiong G., Benz M., Cheng K., Schultink A., Reca I. B., Pauly M. (2011). O-acetylation of Arabidopsis hemicelluloses xyloglucan requires AXY4 or AXY4L, proteins with a TBL and DUF231 domain. Plant Cell 23, 4041–4053 10.1105/tpc.111.091728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glushka J. N., Terrell M., York W. S., O’Neill M. A., Gucwa A., Darvill A. G., Albersheim P., Prestegard J. H. (2003). Primary structure of the 2-O-methyl-alpha-L-fucose-containing side chain of the pectic polysaccharide, rhamnogalacturonan-II. Carbohydr. Res. 338, 341–352 10.1016/S0008-6215(02)00461-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P. B. (1960). Multinet growth in the cell wall of Nitella. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 7, 289–297 10.1083/jcb.7.2.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günl M., Neumetzler L., Kramer F., de Souza A., Schultink A., Pena M., York W. S., Pauly M. (2011). AXY8 encodes an α-fucosidase, underscoring the importance of apoplastic metabolism on the fine structure of Arabidopsis cell wall polysaccharides. Plant Cell 23, 4025–4040 10.1105/tpc.111.089193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang H. C., Geutjes E. J., Grotenbreg G., Pollington A. M., Bijlmakers M. J., Ploegh H. L. (2007). Chemical probes for the rapid detection of fatty-acylated proteins in mammalian cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 2744–2745 10.1021/ja0685001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz-Saad S., McFarlane H. E., Xu S., Divi U. K., Forward B., Western T. L., Kieber J. J. (2011). Cellulose synthesis via the FEI2 RLK/SOS5 pathway and CELLULOSE SYNTHASE 5 is required for the structure of seed coat mucilage. Plant J. 68, 941–953 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch H. C., Galvani C. D., Szarowski D. H., Turner J. N. (2005). Two new fluorescent dyes applicable for visualization of fungal cell walls. Mycologia 97, 580–588 10.3852/mycologia.97.3.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homann U., Meckel T., Hewing J., Hutt M. T., Hurst A. C. (2007). Distinct fluorescent pattern of KAT1::GFP in the plasma membrane of Vicia faba guard cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 86, 489–500 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T. L., Hanson S. R., Kishikawa K., Wang S. K., Sawa M., Wong C. H. (2007). Alkynyl sugar analogs for the labeling and visualization of glycoconjugates in cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 2614–2619 10.1073/pnas.0704664104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Takahasi R., Kobayashi S., Kawase T., Nishinari K. (2002). Gelation behavior of native and acetylated konjac glucomannan. Biomacromolecules 3, 1296–1303 10.1021/bm0255995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T. (1997). O-acetylated oligosaccharides from pectins of potato tuber cell walls. Plant Physiol. 113, 1265–1272 10.1104/pp.113.4.1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jao C. Y., Salic A. (2008). Exploring RNA transcription and turnover in vivo by using click chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15779–15784 10.1073/pnas.0808480105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabel M. A., de Waard P., Schols H. A., Voragen A. G. J. (2003). Location of O-acetylated oligosaccharides isolated from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) xyloglucan. Carbohydr. Res. 340, 1818–1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschani F., Verhelst S. H., van Swieten P. F., Verdoes M., Wong C. S., Wang Z., Kaiser M., Overkleeft H. S., Bogyo M., van der Hoorn R. A. (2009). Minitags for small molecules: detecting targets of reactive small molecules in living plant tissues using “click chemistry.” Plant J. 57, 373–385 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03683.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstens S., Verbelen J. P. (2002). Cellulose orientation in the outer epidermal wall of angiosperm roots: implications for biosystematics. Ann. Bot. 90, 669–676 10.1093/aob/mcf237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho Y., Kim S. C., Jiang C., Barma D., Kwon S. W., Cheng J., Jaunbergs J., Weinbaum C., Tamanoi F., Falck J., Zhao Y. (2004). A tagging-via-substrate technology for detection and proteomics of farnesylated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12479–12484 10.1073/pnas.0403413101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiick K. L., Saxon E., Tirrell D. A., Bertozzi C. R. (2002). Incorporation of azides into recombinant proteins for chemoselective modification by the Staudinger ligation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 19–24 10.1073/pnas.012583299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S., Laosinchai W., Itoh T., Cui X., Linder C. R., Brown R. M., Jr. (1999). Immunogold labeling of rosette terminal cellulose-synthesizing complexes in the vascular plant Vigna angularis. Plant Cell 11, 2075–2086 10.1105/tpc.11.11.2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H. C., Finn M. G., Sharpless K. B. (2001). Click chemistry: diverse chemical functions from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 40, 2004–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupkova E., Immerzeel P., Pauly M., Schmulling T. (2007). The TUMOROUS SHOOT DEVELOPMENT2 gene of Arabidopsis encoding a putative methyltransferase is required for cell adhesion and co-ordinated plant development. Plant J. 50, 735–750 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallana E., Riguera R., Fernandez-Megia E. (2011). Reliable and efficient procedures for the conjugation of biomolecules through Huisgen azide-alkyne cycloadditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 8794–8804 10.1002/anie.201101019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin S. T., Baskin J. M., Amacher S. L., Bertozzi C. R. (2008). In vivo imaging of membrane-associated glycans in developing zebrafish. Science 320, 664–667 10.1126/science.1155106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerouxel O., Choo T. S., Seveno M., Usadel B., Faye L., Lerouge P., Pauly M. (2002). Rapid structural phenotyping of plant cell wall mutants by enzymatic oligosaccharide fingerprinting. Plant Physiol. 130, 1754–1763 10.1104/pp.011965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W. G., Magallon F. G., Fokin V. V., Finn M. G. (2004). Discovery and characterization of catalysts for alkyne-azide cycloaddition by fluorescence quenching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9152–9153 10.1021/ja048664m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Lei L., Somerville C. R., Gu Y. (2012). Cellulose synthase interactive protein (CSI1) links microtubules and cellulose synthase complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 185–190 10.1073/pnas.1200255109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima D. U., Loh W., Buckeridge M. S. (2004). Xyloglucan-cellulose interaction depends on the sidechains and molecular weight of xyloglucan. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 42, 389–394 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link A. J., Vink M. K., Agard N. J., Prescher J. A., Bertozzi C. R., Tirrell D. A. (2006). Discovery of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase activity through cell-surface display of non-canonical amino acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 10180–10185 10.1073/pnas.0601167103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. A., Staehelin L. A. (1992). Domain-specific and cell-type specific localization of two types of cell wall matrix polysaccharides in the clover root tip. J. Cell Biol. 118, 467–479 10.1083/jcb.118.2.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe Y., Nafisi M., Verhertbruggen Y., Orfila C., Gille S., Rautengarten C., Cherk C., Marcus S. E., Somerville S., Pauly M., Knox J. P., Sakuragi Y., Scheller H. V. (2011). Loss-of-function mutation of REDUCED WALL ACETYLATION2 in Arabidopsis leads to reduced cell wall acetylation and increased resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 155, 1068–1078 10.1104/pp.110.168989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S. E., Blake A. W., Benians T. A., Lee K. J., Poyser C., Donaldson L., Leroux O., Rogowski A., Petersen H. L., Boraston A., Gilbert H. J., Willats W. G., Konx J. P. (2010). Restricted access of proteins to mannan polysaccharides in intact plant cell walls. Plant J. 64, 191–203 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S. E., Verhertbruggen Y., Herve C., Ordaz-Ortiz J. J., Farkas V., Pederson H. L., Willats W. G., Knox J. P. (2008). Pectic homogalacturonan masks abundant sets of xyloglucan epitopes in plant cell walls. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 60. 10.1186/1471-2229-8-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris A., Suslov D., Fry S. C., Verbelen J. P., Vissenberg K. (2009). Enzymic characterization of two recombinant xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase (XTH) proteins of Arabidopsis and their effect on root growth and cell wall extension. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 3959–3972 10.1093/jxb/erp229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks M. D., Betancur L., Gilding E., Chen F., Bauer S., Wenger J. P., Dixon R. A., Haigler C. H. (2008). A new method for isolating large quantities of Arabidopsis trichomes for transcriptome, cell wall and other types of analysis. Plant J. 56, 483–492 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohnen D. (2008). Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 266–277 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller I., Marcus S. E., Haeger A., Verhertbruggen Y., Verhoef R., Schols H., Ulvskov P., Mikkelsen J. D., Knox J. P., Willats W. (2008). High-throughput screening of monoclonal antibodies against plant cell wall glycans by hierarchical clustering of their carbohydrate microarray profiles. Glycoconj. J. 25, 37–48 10.1007/s10719-007-9059-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P. J., Swords K. M., Lynch M. A., Staehelin L. A. (1991). Spatial organization of the assembly pathways of glycoproteins and complex polysaccharides in the Golgi apparatus of plants. J. Cell Biol. 112, 589–602 10.1083/jcb.112.4.589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A., Furuta H., Maeda H., Nagamatsu Y., Yoshimoto A. (2001). Analysis of structural components and molecular construction of soybean soluble polysaccharides by stepwise enzymatic degradation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65, 2249–2258 10.1271/bbb.65.774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngouemazong D. E., Jolie R. P., Cardinaels R., Fraeye I., Van Loey A., Moldenaers P., Hendrickx M. (2012). Stiffness of Ca2+-pectin gels: combined effects of degree and pattern of methylesterification for various Ca2+ concentrations. Carbohydr. Res. 348, 69–76 10.1016/j.carres.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H. P., Chakravarthy S., Velasquez A. C., McLane H. L., Zeng L., Nakayashiki H., Park D. H., Collmer A., Martin G. B. (2010). Methods to study PAMP-triggered immunity using tomato and Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 991–999 10.1094/MPMI-23-8-0991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol F., His I., Jauneau A., Vernhettes S., Canut H., Hofte H. (1998). A plasma membrane-bound putative endo-1,4-beta-D-glucanase is required for normal wall assembly and cell elongation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 17, 5563–5576 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa S., Zinkl G. M., Swanson R. J., Maruyama D., Preuss D. (2005). Callose (beta-1,3 glucan) is essential for Arabidopsis pollen wall patterning but not tube growth. BMC Plant Biol. 5, 22. 10.1186/1471-2229-5-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredez A. R., Somerville C. R., Ehrhardt D. W. (2006). Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science 312, 1491–1495 10.1126/science.1126551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. B., Cosgrove D. J. (2012a). Changes in cell wall biomechanical properties in the xyloglucan-deficient xxt1/xxt2 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158, 465–475 10.1104/pp.111.192880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. B., Cosgrove D. J. (2012b). A revised architecture of primary cell walls based on biochemical changes induced by substrate-specific endoglucanases. Plant Physiol. 158, 1933–1943 10.1104/pp.111.192880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattathil S., Avci U., Baldwin D., Swennes A. G., McGill J. A., Popper Z., Bootten T., Albert A., Davis R. H., Chennareddy C., Dong R., O’Shea B., Rossi R., Leoff C., Freshnour G., Narra R., O’Neil M., York W. S., Hahn M. G. (2010). A comprehensive toolkit of plant cell wall glycan-directed monoclonal antibodies. Plant Physiol. 153, 514–525 10.1104/pp.109.151985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M., Albersheim P., Darvill A., York W. S. (1999). Molecular domains of the cellulose/xyloglucan network in the cell walls of higher plants. Plant J. 20, 629–639 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00630.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M., Keegstra K. (2008). Cell-wall carbohydrates and their modification as a resource for biofuels. Plant J. 54, 559–568 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03463.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaucelle A., Louvet R., Johansen J. N., Hofte H., Laufs P., Pelloux J., Mouille G. (2008). Arabidopsis phyllotaxis is controlled by the methyl-esterification status of cell wall pectins. Curr. Biol. 18, 1943–1948 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S., Paredez A., Carroll A., Palsdottir H., Doblin M., Poindexter P., Khitrov N., Auer M., Somerville C. R. (2007). Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15566–15571 10.1073/pnas.0706592104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescher J. A., Dube D. H., Bertozzi C. R. (2004). Chemical remodeling of cell surfaces in living animals. Nature 430, 873–877 10.1038/nature02791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabuka D., Hubbard S. C., Laughlin S. T., Argade S. P., Bertozzi C. R. (2006). A chemical reporter strategy to probe glycoprotein fucosylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 12078–12079 10.1021/ja064619y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refregier G., Pelletier S., Jaillard D., Hofte H. (2004). Interaction between wall deposition and cell elongation in dark-grown hypocotyls cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135, 959–968 10.1104/pp.104.038711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter W. D., Chapple C., Somerville C. R. (1997). Mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana with altered cell wall polysaccharide composition. Plant J. 12, 335–345 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12020335.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtsev V. V., Green L. G., Fokin V. V., Sharpless K. B. (2002). A stepwise huisgen cycloaddition process: copper (I)-catalyzed regioselective “ligation” of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41, 2596–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salic A., Mitchison T. J. (2008). A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2415–2420 10.1073/pnas.0712168105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa M., Hsu T. L., Itoh T., Sugiyama M., Hanson S. R., Vogt P. K., Wong C. H. (2006). Glycoproteomic probes for fluorescent imaging of fucosylated glycans in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12371–12376 10.1073/pnas.0605418103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M., Schwartzberg A. M., Carroll A., Chaibang A., Adams P. D., Schuck P. J. (2010). Raman imaging of cell wall polymers in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 395, 521–523 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C. (2006). Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 53–78 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.022206.160206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C., Bauer S., Brininstool G., Facette M., Hamann T., Milne J., Osborne E., Paredez A., Persson S., Raab T., Vorwerk S., Youngs H. (2004). Towards a systems approach to understanding plant cell walls. Science 306, 2206–2211 10.1126/science.1102765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen I., Willats W. G. (2011). Screening and characterization of plant cell walls using carbohydrate microarrays. Methods Mol. Biol. 715, 115–121 10.1007/978-1-61779-008-9_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser R., Altmann F., Mach L., Glossl J., Steinkellner H. (2004). Generation of Arabidopsis thaliana plants with complex N-linked glycans lacking β-1,2-linked xylose and core α-1,3-linked fucose. FEBS Lett. 561, 132–136 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K., Williamson R. E., Wasteneys G. O. (2000). New techniques enable comparative analysis of microtubule orientation, wall texture, and growth rate in intact roots of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 124, 1493–1506 10.1104/pp.124.4.1493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N. G., Howells R. M., Huttly A. K., Vickers K., Turner S. R. (2003). Interactions among three distinct CesA proteins essential for cellulose synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 1450–1455 10.1073/pnas.0337628100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornoe C. W., Christensen C., Meldal M. (2002). Peptidotriazoles on solid phase: [1,2,3]-triazoles by regioselective copper(I)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of terminal alkynes to azides. J. Org. Chem. 67, 3057–3064 10.1021/jo011148j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanzin G. F., Madson M., Carpita N. C., Raikhel N. V., Keegstra K., Reiter W. D. (2002). The mur2 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana lacks fucosylated xyloglucan because of a lesion in fucosyltransferase AtFUT1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3340–3345 10.1073/pnas.052450699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincken J. P., de Keizer A., Beldman G., Voragen A. G. (1995). Fractionation of xyloglucan fragments and their interaction with cellulose. Plant Physiol. 108, 1579–1585 10.1104/pp.108.4.1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissenberg K., Martinez-Vilchez I. M., Verbelen J. P., Miller J. G., Fry S. C. (2000). In vivo colocalization of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase activity and its donor substrate in the elongation zone of Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 12, 1229–1237 10.2307/3871267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Western T. L., Burn J., Tan W. L., Skinner D. J., Martin-McCaffrey L., Moffatt B. A., Haughn G. W. (2001). Isolation and characterization of mutants defective in seed coat mucilage secretory cell development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127, 998–1011 10.1104/pp.010410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Williams M., Bernard S., Driouich A., Showalter A. M., Faik A. (2010). Functional identification of two nonredundant Arabidopsis alpha (1,2) fucosyltransferases specific to arabinogalactan proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13638–13645 10.1074/jbc.M109.088781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B., Wang X., Zhu M., Zhang Z., Hong Z. (2011). CalS7 encodes a callose synthase responsible for callose deposition in the phloem. Plant J. 65, 1–14 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Purugganan M. M., Polisensky D. H., Antosiewicz D. M., Fry S. C., Braam J. (1995). Arabidopsis TCH4, regulated by hormones and the environment, encodes a xyloglucan endotransglycosylase. Plant Cell 7, 1555–1567 10.1105/tpc.7.9.1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]