Abstract

In a marked shift from the modern positivist materialist philosophy that influenced medical education for more than a century, Western medical educators are now beginning to realize the significance of the spiritual element of human nature. Consensus is currently building up in Europe and North America on the need to give more emphasis to the study of humanities disciplines such as history of medicine, ethics, religion, philosophy, medically related poetry, literature, arts and medical sociology in medical colleges with the aim of allowing graduates to reach to the heart of human learning about meaning of life and death and to become kinder, more reflective practitioners. The medicine taught and practiced during the Islamic civilization era was a vivid example of the unity of the two components of medical knowledge: natural sciences and humanities. It was also a brilliant illustration of medical ethics driven by a divine moral code. This historical fact formed the foundation for the three medical humanities courses presented in this article reporting a pedagogical experiment in preparation for starting a humanities program in Alfaisal University Medical College in Riyadh. In a series of lectures alternating with interactive sessions, active learning strategies were employed in teaching a course on history of medicine during the Islamic era and another on Islamic medical ethics. Furthermore, a third course on medically relevant Arabic poetry was designed and prepared in a similar way. The end-of-the-course feedback comments reflected effectiveness of the courses and highlighted the importance of employing student-centered learning techniques in order to motivate medical students to become critical thinkers, problem solvers, life-long learners and self-learners.

Keywords: Medical education, active-learning strategies, critical-thinking skills, Islamic studies, Islamic medical ethics, History of medicine, Arabic medical poetry, Islamic civilization, Modern medicine, Post-modern medicine

INTRODUCTION

Lately, many medical educators worldwide are talking enthusiastically about “the medical humanities” as a field of enquiry and teaching, even within the already tightly packed undergraduate curriculum! Consensus is currently building up in Europe and North America on the need to give more emphasis to the study of humanities disciplines such as history of medicine, ethics, religion, philosophy, medically related poetry, literature, arts and medical sociology at the undergraduate level in medical colleges.[1–6]

Centers for the study of medical humanities are arising, conferences are held and many books, scientific periodicals as well as blogs are published.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Medicine and the humanities have forever been interwoven. Great literature has been written by and about physicians. Clinical practice has always operated within the guidance of: ethics, law and religion. The work and science of healing have always been a focus of philosophers, historians, artists and poets. The care of the sick and dying has reciprocally called the attention of sensitive physicians to the meaning and chronicles of human life.

However, from European Renaissance to the present time, modern medicine stands under the principle of secularization with the consequent loss of religious and philosophical reflection, dichotomy of natural sciences and humanities in addition to separation of the physical and mental or social approaches to the understanding of humanity.[7–9]

Accordingly, in the last century, the focus was largely on giving students the scientific knowledge and skills required of a doctor, but this was not enough. It all came on the expense of their professionalism due to the lack of emphasis on the moral, spiritual, cultural and societal aspects of medical practice.

Furthermore, by tacitly closing itself to the realms of metaphysics and refusing to submit itself to thousands of years of accumulated wisdom from faith traditions, which, in addressing the inner peace attainable by humans, have too much in common to disregard – the field of psychology/psychiatry has done a great disservice to postmodern humankind.[10] Is it possible to restore a model of the healing profession that encompasses a sense of addressing spiritual/religious concerns from not only a therapeutic perspective but beyond?

WHAT DID MODERN MEDICINE MISS WITH ITS LACK OF INTEREST IN THE MEDICAL HUMANITIES?

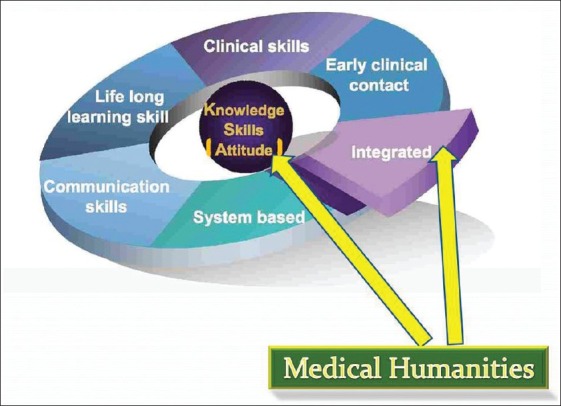

Medical humanities is an interdisciplinary exploration of how such disciplines can engage and illuminate: the nature, goals and practice of medicine. It explores the integration of the scientific understanding of physical nature and the humanistic understanding of experience. The mission is to advance knowledge and appreciation of the humanities, ethics and law, as they interface with the science and art of medicine, through education and service. The goal is to integrate humanities into the medical curriculum [Figure 1] to help clinicians to reach to the heart of human learning about meaning of life and death and to become kinder, more reflective practitioners.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the two-fold role of medical humanities in developing a professional attitude as well as integrating all the other components of the medical curriculum. Modified from a diagram available at http://www.kmu.edu.tw/~spbm/eng-web/programs/overview.html with the permission of Dean Lai CS, College of Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University

Medical humanities also points the way toward remedial education in habits of the heart. Nowadays, the Western culture is skeptical of virtue and, in particular, glorifies self-aggrandizement over altruism. Thus, today's medical students usually lack moral education and often a belief in virtue. These factors make them more vulnerable to a culture of medicine that reinforces egoism, cynicism and a sense of entitlement.[11] Medical humanities, whether history or ethics, poetry or arts or whatever it is, may assist students in resisting these negative forces by opening their hearts to empathy, respect, genuineness, self-awareness and reflective practice.[11]

Medicine and Science are standing at their crossroads today. With the ever increasing technological progress and scientific discoveries, the art of healing has been transformed to a highly specialized one, utilizing sophisticated machinery linked to that marvel of the electronic age, the computer.

Decisions are now based on computer printouts of metabolic processes, resulting in the doctor becoming part of the robotic process himself, becoming dehumanized to the extent that he comes to rely on miracle drugs and wonder machines, and becoming oblivious of the Supreme Healer, the Creator and Sustainer of all life, Allah, the Beneficent and the Merciful.

In academia, it is very crucial to strike a harmonious balance between the two major branches of knowledge; namely, natural sciences and technology in one hand and social sciences and humanities in the other. The importance of striking a harmonious balance is increasingly felt to match with the growing detrimental effects of the already well-established and strong-rooted materialism. We have to be able to produce not only graduates with great mental and intellectual capability but also with strong emotional and spiritual stability.[12]

ARE WE, NOW, WITNESSING A NEW TREND IN WESTERN MODERN MEDICAL EDUCATION?

Indeed, it is for the aforesaid reasons that courses in humanities are rapidly spreading in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education in the West and, to a lesser extent, in the East. These courses mainly include history of science and the study of ethics either separately or as part of a philosophy-of-science program. In many universities, the courses in humanities for medical students also include other relevant topics like religion, literature, poetry and legal studies.

In 1999, the European Federation of Internal Medicine, the American College of Physicians and the American Board of Internal Medicine launched the Medical Professionalism Project, which placed medical ethics at the center of a charter of behavior and attitudes for all physicians. The project emphasized the role of personal qualities in the building up of professionalism. Also stressed in that project is the fact that knowledge and skills alone are not enough to achieve professionalism.[13,14]

In the same year, 1999, the General Medical Council in United Kingdom recognized that medical education needed a radical rethink and, in their document, Tomorrow's Doctors, recommended a greater focus on education, as opposed to training, in the undergraduate degree. The good doctor, as the General Medical Council suggests, must be an educated doctor, and this is one of the major areas where arts and humanities subjects might make a contribution.[15]

In a marked shift from the modern positivist materialist philosophy that influenced medical education for more than a century, Western medical educators are now beginning to realize the significance of the spiritual element of human nature. In their book “Medical Humanities” published by the British Medical Journal Book in 2001, Martyn Evans and Ilora Finlay stated that, “As medicine concerns our physical nature, it seems well grounded in the natural sciences, but our physical nature is not the whole story about us. Moreover, we are not simply physical beings with a merely additional psychological, personal or spiritual aspect. Our nature is one in which the personal is integrated with the physical, so that the natural sciences on their own, cannot tell the full story even about our physical selves.”[1]

“And if we take the view, above, that human nature integrates the physical and the personal, then we should expect to find that the humanities are not an (optional) addition to scientific medical knowledge but hold an integral place with the natural sciences at the core of clinical medicine. Together – in a sense fused together, if we knew how – the natural sciences and the humanities hold the resources for trying to understand and respond to the human experiences of ill health, disability, incapacity, and suffering."[1]

MEDICAL EDUCATION IN NON-WESTERN PARTS OF THE WORLD

With a few exceptions, medical education in the Arab world is still following the same principles of Modern Western Medicine prior to the aforementioned recent changes; that is to say before the postmodern era. Up till now, the medical humanities are not incorporated in the curriculum of most of the region's medical colleges, with the few exceptions where medical ethics are included as part of the community medicine programs or where some courses on Islamic studies, Arabic studies or local history are given as a university general requirement.

On the other hand, rapid global expansion of the medical humanities was featured across Asia (China, Japan, Indonesia, India, Korea and Singapore) during the past 5 years. According to Hooker and Noonan (2011), what often emerged in those regions was a quasi-Western canon of medical humanities (in history, philosophy, literature and art) in which the diversity, sophistication and richness of different cultural traditions was uncomfortably marginalized.[16]

OUR APPROACH AND PROPOSAL

Realizing the richness of the medicine taught and practiced during the Islamic civilization era as a vivid example of the unity of the two components of medical knowledge, natural sciences and humanities, in addition to its being a bright illustration of medical ethics driven by a divine moral code, the following approach to the teaching of medical humanities at Alfaisal University Medical College in Riyadh was thought of, designed and tried.

The basic idea of that approach was to utilize the two core-curriculum components, Islamic studies and Arabic studies, as the medium for teaching the courses of a newly designed Medical Humanities Program.

Thus, instead of the standard content of the Islamic studies and Arabic studies, which were, to a great extent, already studied before in intermediate and secondary schools and were also not tailored to the specific needs of different colleges, we designed and prepared the three following courses:

History of the medicine taught and practiced during the Islamic civilization era.

Islamic medical ethics.

Arabic medical poetry.

I. History of medicine during the Islamic civilization

Aim of the course

History of medicine is increasingly viewed as a significant dimension of the professional, intellectual and humanistic development of medical students.

The use of history can potentially humanize medicine, help students refine their critical-thinking skills and promote a deeper understanding of scientific concepts.

A knowledge and ongoing study of the history of medicine can help determine research directions, adjust current practice trends and serve as a tool in contemporary medical education.

Course objectives

Cultivate interest in the study of history of medicine and develop ability to link the past with the present for the benefit of the future.

Add more interest to the study of the contemporary branches of medicine by being able to follow the various phases of its development. This could stimulate and nurture the potential of talented students for innovation and prepare their abilities to add more new knowledge, inventions and discovery.

Nurture the critical thinking involved in learning history of science. This will help the student to reflect on the rise and fall of different civilizations and discover the relation between the progress of science in an era and the prevailing beliefs of its people.

Benefit the attitude of students, making them more rounded, humane and able.

Broaden the student outlook through the revealed interchange between consecutive civilizations. This will nurture the feeling of unity of mankind.

Fill a gap in the currently available history of medicine bibliography during that Islamic era focused upon in the course.

Prove to the students how Islamic faith and teachings stimulated the minds to discover and advance scientific medical knowledge in addition to achieving a high standard of medical ethics.

Description of content

The course consists of a series of lectures and interactive sessions based, mainly, on the study of primary-source authentic historical documents from the Islamic era. Relevant excerpts from those original works are frequently quoted and translated into English.

II. Islamic medical ethics

Aim

Consensus is currently building up among medical educators on the need to give more emphasis to the study of ethics at the undergraduate level.

This will help not only in learning the standards of professional competence and conduct but also in preparing graduates to handle the ethical dilemmas arising from recent advances in medical practice and science applications.

Furthermore, sound ethical practices go hand in hand with scientifically valid research.

The course also aims to give students an appreciation of important historical and theoretical developments of medical ethics.

In addition, the course explains the effect of different outlooks in philosophy on the ethical decision-making process of physicians, with special reference to the necessity of putting together the comprehensive principles of Islam in this field.

In this course

Students will develop a critical understanding of the ethics applied to their future practice.

Students will also learn how to maintain high ethical standards of research, particularly when involving human subjects.

Common ethical theories will be examined in order to demonstrate the contested nature of ethics.

Islamic values and moral principles related to both the practice of and research into medicine will be explored.

Practical applications of ethics to professional issues will be addressed together with legal aspects.

Teaching methods used

In the year 2009, the first author was invited by the Dean of Alfaisal University Medical College to teach the two above-mentioned newly designed and prepared courses for a full semester. The following teaching methods were used:

The lectures and the alternating interactive sessions employ active learning strategies. Whereas the interactive sessions are wholly assigned to student-centered learning techniques, lectures also include structured student activity and participation, individually, in pairs or in small groups.

As problem-based learning (PBL), now a standard technique in the teaching of medicine and science, has, recently, proved itself a workable method in the humanities,[17,18] it was used in the interactive sessions of these courses.

In the medical ethics course, sets of problems; simulations, ethical dilemmas, case studies, medical diagnoses or decisions, legal disputes, public health policy issues have been used as the framework for student learning.

The students, divided in small groups, formulate an understanding of the problem and key questions that have to be answered in order to “solve” it. They examine relevant resources to obtain the data necessary to develop a tentative solution and they then write group or individual papers articulating their solutions.

The students are encouraged to do their own search for the required library and internet resources. However, guidance and help are given to them when needed. In order to develop the students’ analytical and decision-making abilities, the case scenarios are made as realistic as possible and will represent different ethical practice and research problems.

In the PowerPoint lecture presentations, pictures from pages of relevant original Arabic sources and manuscripts are abundantly included for the purpose of documentation and in order to stimulate the interest and curiosity of students. Ample time for discussion is given at the end of each lecture.

In addition to issue-based learning, the interactive sessions also include small group discussions and presentations. This aims at engaging students in various forms of enquiry-based learning by developing their own investigative skills and building their abilities to perform effective library-based or computer-based searches.

The adequate number of interactive sessions as well as the interactive nature of the lectures involve and engage all students and ensure their participation in this critical thinking and active learning process, which will eventually cultivate a research-based approach to projects and processes.

Assessment

In both courses, mini research assignments and projects were used for mid-term and final assessments of students’ performance.

III. Arabic medical poetry

Aim

The course aims to provide Arabic poetry content directly relevant to medicine that has the potential to promote professionalism in medical graduates and, consequently, leads to improved patient care.

The course considers Arabic poetry to show how poets and poet-physicians have dealt with illness, pain, disability, birth, death and dying and how the skilled imaginative exploration of these subjects increases understanding of the human condition, especially of human suffering and, thus, contributes to compassionate patient care.

The focus is on the experience, both of patients and of those who care for them, as well as on the works of poets who documented in a moving and impressive way the effects of various illnesses, particularly endemic, epidemic and environmental health problems, on both individuals and their families and on the society as a whole.

Health-related Arabic poetry also reveals an abundant data source for the study of philosophy and history of medicine as well as social medicine and medical ethics. Moreover, Arabic poetry was previously commonly used as an efficient means for didactic teaching of medicine.

Course objectives

Provide a means for a better understanding of the suffering of patients and their families.

Cultivate an attitude of sympathy and mercy for patients. This will help, after graduation, in the building up of a good doctor–patient relationship.

Develop an understanding of the psychological and social effects of illnesses on the patient and his family.

Enhance students’ abilities to subordinate their self-interests and respond to societal needs as well as adhering to high ethical and moral standards.

Teach students to reflect on broader questions about the healthcare system or their place in it. This reflective practice will enhance notions of self-awareness and greater insight into one's own personal values and assumptions.

Provide, in a poetic impressive way, some practical examples of medical ethical encounters as well as data on sociology, philosophy and history of medicine.

Students’ feedback

Thirty-seven students in the Ethics and 24 in the History course completed the semester and presented their end-of-the-course feedback report. Both courses were received well by all the students with enthusiasm and a favorable response. Suggestions for improvements were made, first to avoid the timing of the classes at the end of the day. Two students also suggested inviting scholars, intellectuals and relevant spokespersons from outside the university to participate in the interactive sessions when discussing healthcare-related topics. Another student proposed visits to primary care centers and hospitals in order to be exposed to real-life medical ethical situations.

In the following section, some representative samples of the students’ feedback comments are given, starting with the Islamic medical ethics course:

Sample 1

This student said: “…This course helped us in developing skills in presentation, research and by that, of course, getting the information we are required to know in an advanced way, rather than the old study-book method previously taught in old school universities…”

He concluded: “I extremely enjoyed taking this course that helped me to understand the morals and ethics of life and how our great religion applies it into my career.”

Sample 2

Another student said: “……this course has many advantages which have reflected on my personality, attitude, and my life. …Finally, I think the Islamic course has really changed my views and made me find and search more about my religion.”

Sample 3

Among this student's comments is the following: “…I liked the idea of making the exams team work (mini research projects) rather than individually written oriented exams, this improves our skills of communication throughout research, expose us to each other more and can increase the skill of leadership during the work.”

Sample 4

Another student said: “I really liked the way the course was running: by having Saturdays for discussions and presentations and Mondays for lectures. We had lots of hot discussion. During such discussions, I learned a lot of new things and how to look at different point of views. I learned how to argue and discuss with my colleagues in a professional Islamic manner. I discovered some qualities in my colleagues, I did not know about them before that course. Honestly, this course put me, as they say, right on the spot when (the professor) gives us an example of a situation that we might face in our daily lives as Muslim physicians and how to deal with it in the light of Islam. Having a Professor with a strong medical background was one of the fundamental reasons for having this great and successful course.”

Sample 5

This student said: “…In this course, I have learned that I mustn’t learn for grades only. Instead, I must learn to become well-educated, to become an active member in society, to help people, to advise them as to what is right and what is wrong, and most importantly, to become a good doctor as it is going to be my profession and life in the future.

I was motivated by the professor to become a critical thinker, a problem solver, a life-long learner and a self-learner. Furthermore, I was taught to do my assignments (midterm mini case exam, final exam and weakly presentations) whatever the cost, and yet, I have to hand in my assignments at the appointed time. I have been taught the dangerous effects of cheating and plagiarizing. I have learned group working skills, which is of great importance as you are going to be working with physicians, clinicians and researchers that you might not have a previous experience with in your upcoming future.

I have learned how to respect religions and how to respect other people's ideas, and yet, how to debate/support/argue the points presented during the interactive sessions logically and effectively.

Moreover, I learned how to do medical/scientific research, and more surprisingly, I did my first Islamic research (Impact of the Early Islamic Era on Medical Accountability) as my midterm exam, followed by my final exam research paper (Brief History of Medical Accountability).

Sample 6

This student concluded his feedback report by saying: “…With all these comments in mind, ethics should become a key course in the education of the physician.”

Similar feedbacks were also obtained from the history course candidates. Here are two representative samples:

Sample H 1

This student said: “When I heard that we are taking an Islamic course, I thought we will take a typical boring course about obvious Islamic principles. However, when we started the course I was surprised about the rich interesting amount of content that we are taking. We started from the old civilizations and then compared them with the Islamic culture and contributions to the world.

I personally enjoyed the course and it was a different experience than the Islamic courses that we take in our high schools. Furthermore, the idea of having research projects about interesting topics and Muslim scholars was amazing and beneficial to me. I started to learn how to do proper research. This has benefited me in that I now can do researches about anything I am interested in. Also, the involvement of students in the lecture and giving lectures by themselves was a great idea. This way allowed the students to join the professor in the learning…”

Sample H 2

And, this student said: “..The study of civilizations is significant to our modem world. The best way to have a better future is to study and observe the histories of civilizations. The study of civilization helps us in understanding the complications of scientific theories.”

He added: “……To conclude, our course is very unique and interesting to the extent that I might consider taking it one more time in order to absorb the amount of information that is in that course.”

All those end-of-the-course feedback comments reflected the effectiveness of the courses and highlighted the importance of employing student-centered learning techniques in order to motivate medical students to become critical thinkers, problem solvers, life-long learners and self-learners.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans M, Finlay IG. London: BMJ Books; 2001. Medical Humanities; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macnaughton J. The humanities in medical education: context, outcomes and structures. Medi Humanit. 2000;26:23–30. doi: 10.1136/mh.26.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant VJ. Making room for medical humanities. Med Humanit. 2002;28:45–8. doi: 10.1136/mh.28.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunders C, Mack M, Woods A. Imaginative Worlds: Medical Humanities and ‘the uses of literature’. Inventions of the Text Seminar Series 2010-2011: The Uses of Literature. [Last cited on 2012 Jan 06]. available from: ‘/http://medicalhumanities.wordpress.com/2011/01/17/imaginative-worlds-medical-humanities-and-‘the-uses-ofliterature .

- 5.Brody H. Defining the Medical Humanities: Three Conceptions and Three Narratives. J Med Humanit. [Last cited on 2009 Nov 20]. available from: https://wwwcache1.kcl.ac.uk/content/1/c6/07/75/04/MedicalHumanitiesHBrody.pdf . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Banaszek A. Medical humanities courses becoming prerequisites in many medical schools. CMAJ. 2011;183:E.441–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommerville M. The search for ethics in a secular society. In: Sommerville Margaret., editor. Ethics of Science and Technology: Explorations of the frontiers of science and ethics. Paris: UNESCO; 2006. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall PA. Anthropology and Bioethics. Med Anthropol Q. 1992;6:49–73. doi: 10.1525/maq.1992.6.1.02a00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Engelhardt D. Teaching History of Medicine in the Perspective of “Medical Humanities”. Croat Med J. 1999;40:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan F. Spirituality, Religious Wisdom, and the Care of the Patient: Faith and Care of the Patient: An Islamic Perspective on Critical Illness. YJHM (The Yale Journal for Humanities in Medicine) [Last accessed on 2002 June 4]. Available from: http://yjhm.yale.edu/archives/spirit2003/faith/fkhan1.htm .

- 11.Coulehan J. What is medical humanities and why? Comment, Medical Ethics on Stage, Literature, Arts and Medicine Blog. [Last accessed on 2008 Jan 25]. Available from: http://medhum.med.nyu.edu/blog/?p=100 .

- 12.School of Humanities, University Sains Malaysia. About Islamic Studies. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 06]. Available at: http://www.hum.usm.my/ppikv2/ug_islamic.asp .

- 13.Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physicians’ charter. Lancet. 2002;359:520–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A Physician Charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.General Medical Council. Tomorrow's Doctors: Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education; GMC Publication. Republished September 2009. [Last cited on 2012 Jan 06]. Available from: http://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/TomorrowsDoctors_2009%281%29.pdf .

- 16.Hooker C, Noonan E. Medical humanities as expressive of Western culture. Med Humanit. 2011;37:79–84. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2011-010120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchings B, O’Rourke K. Problem-based learning in literary studies. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education. 2002;1:73–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tysinger JW, Klonis LK, Sadler JZ, Wagner JM. Teaching ethics using small-group, problem-based learning. J Med Ethics. 1997;23:315–8. doi: 10.1136/jme.23.5.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]