Abstract

T follicular helper (Tfh) cells are critical for providing the necessary signals to induce differentiation of B cells into memory and Ab-secreting cells. Accordingly, it is important to identify the molecular requirements for Tfh cell development and function. We previously found that IL-12 mediates the differentiation of human CD4+ T cells to the Tfh lineage, because IL-12 induces naive human CD4+ T cells to acquire expression of IL-21, BCL6, ICOS, and CXCR5, which typify Tfh cells. We have now examined CD4+ T cells from patients deficient in IL-12Rβ1, TYK2, STAT1, and STAT3 to further explore the pathways involved in human Tfh cell differentiation. Although STAT1 was dispensable, mutations in IL12RB1, TYK2, or STAT3 compromised IL-12–induced expression of IL-21 by human CD4+ T cells. Defective expression of IL-21 by STAT3-deficient CD4+ T cells resulted in diminished B-cell helper activity in vitro. Importantly, mutations in STAT3, but not IL12RB1 or TYK2, also reduced Tfh cell generation in vivo, evidenced by decreased circulating CD4+CXCR5+ T cells. These results highlight the nonredundant role of STAT3 in human Tfh cell differentiation and suggest that defective Tfh cell development and/or function contributes to the humoral defects observed in STAT3-deficient patients.

Introduction

The generation of robust Ab responses is crucial for the correct functioning of the immune system. The importance of this is apparent in diseases that result from dysregulated humoral immune responses. For example, immunodeficient states and autoimmune disorders can develop as a consequence of impaired or exaggerated Ab responses, respectively. Thus, it is imperative to identify factors that control Ab responses. Early studies found that T cells play an important role in initiating Ab responses (reviewed in Tangye et al1). This was mediated by instructive signals in the form of cell–cell contacts and secretion of soluble mediators such as cytokines. More recently, a subset of CD4+ T cells with specialized B-cell helper capabilities was identified that is now referred to as T follicular helper (Tfh) cells.2,3 Tfh cells are identified by several characteristics that also serve functional roles. Thus, Tfh cells express the chemokine receptor CXCR5,2,3 which facilitates their positioning to B-cell follicles in secondary lymphoid tissues, and the transcription factor Bcl-6,4 which is required for the commitment of naive CD4+ T cells to the Tfh lineage.5–7 Tfh cells also express the costimulatory molecules CD40L, ICOS, OX40, and members of the SLAM family, as well as the cytokine IL-21,2–4,8–12 all of which play important roles in the induction of T cell–dependent (TD) B-cell activation and differentiation.

Because of the importance of Tfh cells in regulating Ab responses, much work has been performed to determine the requirements for their differentiation from naive CD4+ T cells. It was initially found that IL-21 was required for the development of murine Tfh cells.13,14 This was later expanded to include IL-6 and IL-27.15–17 However, conflicting findings have been made about the relative importance of IL-6 and IL-21 to murine Tfh cell formation18,19; this may reflect redundancy because these cytokines, as well as IL-27, can operate through STAT3.20,21 We and others previously showed that IL-12 is the key cytokine implicated in the differentiation of human Tfh cells in vitro.11,22 IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, and IL-27 also induce human Tfh-like cells in vitro, albeit to a much lesser extent than IL-12.11,17,22 We have now extended these observations by investigating the molecular requirements for the differentiation of naive human CD4+ T cells into Tfh cells. This was achieved by studying patients with primary immunodeficiencies resulting from mutations in IL12RB1, STAT1, STAT3, and TYK2. IL-12–mediated induction of human Tfh-like cells was abolished in the absence of IL-12Rβ1 or TYK2, and significantly reduced in CD4+ T cells deficient in STAT3 function. In contrast to the effects of IL-12, induction of Tfh cells by IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, and IL-27 was completely dependent on STAT3. These studies indicate that multiple cytokine pathways are involved in the differentiation of human Tfh cells, and IL-12 most efficiently induces human Tfh cells predominantly in a STAT3-dependent manner. This defect in generating Tfh cells from STAT3 mutant (STAT3MUT) CD4+ T cells would contribute to impaired TD humoral immune responses observed in patients with STAT3 mutations. In contrast, the ability of non–IL-12 cytokines to induce Tfh cell function is sufficient to elicit intact Ab responses in persons with impaired IL-12R signaling.

Methods

Human patient samples

Patients with mutations in IL12RB1, STAT1, TYK2, and STAT3 have been previously described (Table 123–28). PBMCs were isolated from these patients and healthy donors (Australian Red Cross). Tonsils were obtained from St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney. All studies were approved by Institutional Human Research Ethics Committees, and all participants gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Primary immunodeficient patients

| Disease | Patient ID | Mutation/genotype |

|---|---|---|

| MSMD (IL-12Rβ1 deficiency) | IL12RB1#1 | 1745_1746insCA+1483 + 182-1619-1073del |

| IL12RB1#2 | 628_644dup | |

| IL12RB1#3 | R173P | |

| IL12RB1#4 | 1791 + 2T > G | |

| IL12RB1#5 | C198R | |

| IL12RB1#6 | 1623_1624delinsTT | |

| MSMD + viral infection | STAT1#1 | 1928insA (homozygous) |

| (STAT1 deficiency) | STAT1#2 | P696S (homozygous) |

| STAT1#3 | P696S (homozygous) | |

| MSMD only | STAT1#4 | Q463H/WT |

| (STAT1 deficiency) | STAT1#5 | L706S/WT |

| STAT1#6 | L706S/WT | |

| AD-CMC | STAT1gof#1 | A267V |

| STAT1gof#2 | A267V | |

| STAT1gof#3 | A267V | |

| AD-HIES | STAT3#1 | R382Q |

| STAT3#2 | V637M | |

| STAT3#3 | R382Q | |

| STAT3#4 | H437P | |

| STAT3#5 | Q644P | |

| STAT3#6 | S465F | |

| STAT3#7 | Y657N | |

| STAT3#8 | R382W | |

| STAT3#9 | L706M | |

| STAT3#10 | L706M | |

| STAT3#13 | V463del | |

| STAT3#14 | V463del | |

| STAT3#15 | R593P | |

| STAT3#16 | V463del | |

| AR-HIES (incl infection with mycobacteria, viruses and fungi) | TYK2#1 | 550_553GCTTdel (homozygous) |

| MSMD + viral infection | TYK2#2 | 2292-2301del |

MSMD indicates Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease; WT, wild type; AD-CMC, autosomal dominant chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis; AD-HIES, autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome; AR-HIES, autosomal recessive hyper-IgE syndrome; and gof, gain-of-function

Antibodies

Alexa-647–conjugated anti–IL-21, biotinylated anti-ICOS, PE–anti-CD4, Pacific Blue–anti-CD4, peridinin chlorophyll protein complex (PerCP)/cyanine 5.5–anti-CD45RA, anti-IFNγ, and FITC–anti-CD45RA were purchased from eBiosciences. Alexa-647–anti-CXCR5, allophycocyanin–anti-CD38, FITC–anti-CD20, PE–anti-CD4, anti-CD27, PerCP–anti-CD3 mAb, and streptavidin–PerCP were purchased from Becton Dickinson. Allophycocyanin–anti-CD4 was purchased from Caltag, and FITC–anti-CCR7 was purchased from R&D Systems.

CD4+ T-cell isolation

CD4+ T cells were isolated from healthy donors or immunodeficient patients with the use of Dynal beads.23 Peripheral blood (PB) CD4+ T cells were labeled with anti-CD4, anti-CD45RA, and anti-CCR7, and naive CD45RA+CCR7+ CD4+ T cells were isolated (> 98% purity) with the use of a FACSAria (BD Biosciences).

Cell cultures

Naive PB CD4+ T cells were labeled with CFSE (Molecular Probes) and cultured with T-cell activation and expansion beads (anti-CD2/CD3/CD28; Miltenyi Biotec) alone (nil culture) or under Th1 (IL-12 [20 ng/ml; R&D systems]), Th2 (IL-4 [100 U/ml]), or Th17 (IL-1β [20 ng/ml; Peprotech]), IL-6 (50 ng/mL; PeproTech), IL-21 (50 ng/mL; PeproTech), IL-23 (20 ng/mL; eBioscience), anti–IL-4 (5 μg/mL), and anti-IFNγ (5 μg/mL; eBioscience)23,29 polarizing conditions, or with IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, or IL-27 (50 ng/mL; eBioscience) alone. After 4 or 5 days, expression of intracellular cytokines, transcription factors, and surface phenotype of cells determined.

T- and B-cell coculture assays

Naive CD4+ T cells were activated for 5 days (see previous section), treated with mitomycin C (100 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and then cocultured at a 1:1 ratio (50 × 103/200 μL/well) with sort-purified allogeneic naive (CD20+CD27−CD38inter) tonsillar B cells.11,29 After 7 days Ig secretion was determined by ELISA.29

Cytokine and transcription factor expressions

Activated CD4+ T cells were restimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (100 ng/mL) and ionomycin (750 ng/mL) for 6 hours, with Brefeldin A (10 μg/mL) added after 2 hours. Cells were then fixed with formaldehyde, and expression of cytokines was detected by intracellular staining.23,29 RNA was extracted with the use of RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) and transcribed into cDNA with the use of random hexamers and Superscript III (Invitrogen). All quantitative PCR (qPCR) primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) were designed with Roche UPL Primer Design Program. Primer sequences, Roche UPL probes, and size of each amplicon are listed in Table 2. qPCR was performed with Roche LightCycler 480 Probe Master Mix and Roche Lightcycler 480 System with the following conditions: denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes; amplification for 45 cycles at 95°C for 10 seconds, 65°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 5 seconds; and cooling at 40°C for 30 seconds. All reactions were standardized to GAPDH.

Table 2.

Primers for qPCR

| Gene | Primers | UPL probe | Amplicon size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCL6 | fwd: gagctctgttgattcttagaactgg | 9 | 110 |

| rev: gccttgcttcacagtccaa | |||

| TBX21 | fwd: tgtggtccaagtttaatcagca | 9 | 77 |

| IL21 | rev: tgacaggaatgggaacatcc | 7 | 68 |

| fwd: aggaaaccaccttccacaaa | |||

| rev: gaatcacatgaagggcatgtt | |||

| IFNG | fwd: ggcattttgaagaattggaaag | 21 | 112 |

| rev: tttggatgctctggtcatctt | |||

| GAPDH | fwd: ctctgctcctcctgttcgac | 60 | 112 |

| rev: acgaccaaatccgttgactc |

Results

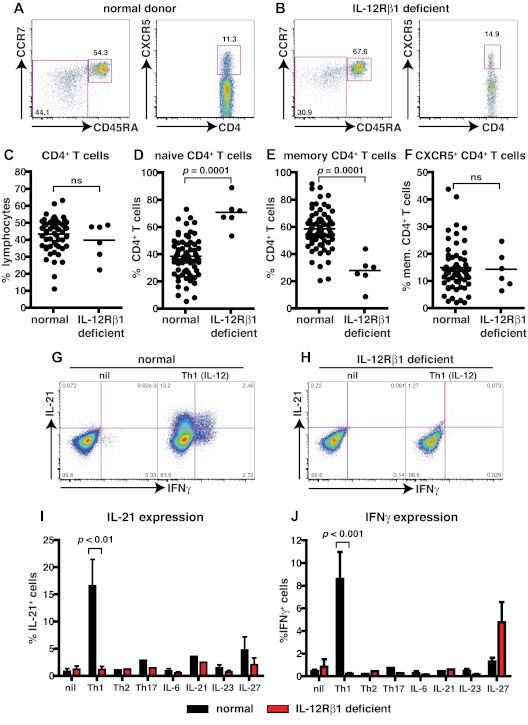

Patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 have altered differentiation of CD4+ T cells in vivo

IL-12 can induce human naive CD4+ T cells to differentiate into IL-21–expressing cells that resemble Tfh cells in vitro.11,22 To investigate this function of IL-12 further, we examined patients with homozygous or compound heterozygous null mutations in IL12RB1.26 We first determined the frequency of total CD4+ T cells and CD4+ T cells with a naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), memory (CD45RA−CCR7+/−), or Tfh (CXCR5+) phenotype in healthy donors (age range, 16-64 years) and patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 (Figure 1A-D,F). Patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 had a normal frequency of CD4+ T cells (Figure 1; Table 3). In contrast, they had a significant increase in the frequency of naive and a corresponding significant decrease in memory CD4+ T cells (Figure 1A-E; Table 3). When the phenotype of CXCR5+ T cells was analyzed, ∼ 90% were found within the CD45RA− (ie, memory) subset (Table 32,3,11). Therefore, we analyzed the frequency of both CXCR5+CD45RA− and CD45RA+ T cells in healthy donors and in patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1. No significant difference was observed for the frequency of circulating CD4+ CXCR5+CD45RA− or CD45RA+ Tfh-like cells in healthy donors and patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 (Figure 1A-B,F; Table 3).

Figure 1.

Naive CD4+ T cells deficient for IL-12Rβ1 fail to differentiate into IL-21–expressing cells in response to IL-12. (A-F) The frequency of total CD4+ T cells, and naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), memory (CD45RA+CCR7−/+), and CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells, in PBMCs was determined for healthy donors and patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1. (A-B) Representative dot plots from 1 donor and 1 patient. (C-F) The frequency of (C) total, (D) naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), (E) memory (CD45RA+CCR7−/+), and (F) CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells from all healthy donors (total CD4+ T cells, n = 54; naive CD4+ T cells, n = 70; memory CD4+ T cells, n = 70; CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells, n = 61) and patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 examined (n = 6). (G-J) Naive CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy donors (n = 5) and patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 (n = 5) were cultured for 5 days under neutral (nil); polarizing Th1, Th2, or Th17 conditions; or in the presence of IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, or IL-27, and intracellular expression of IL-21 and IFNγ were then determined. (G-H) Representative dot plots of IL-21 and IFNγ expression by activated naive CD4+ T cells from 1 donor and 1 patient deficient for IL-12Rβ1. (I-J) Percentage of activated normal and IL-12Rβ1–deficient naive CD4+ T cells induced to express (I) IL-21 or (J) IFNγ in response to the indicated culture. The values represent the mean ± SEM.

Table 3.

CD4+ T-cell subsets in primary immunodeficiencies

| PID | CD4+ T cells | Naive CD4+ T cells | Memory CD4+ T cells | CXCR5+CD45RA+ CD4+ T cells | CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL12RB1 (n = 6) | 40 ± 4.4 | 71 ± 4.7 | 28 ± 4.7 | 1.6 ± 0.46 | 14 ± 2.8 |

| STAT1 (n = 6) | 40* | 41 ± 10 | 56 ± 10 | 3.9 ± 0.68 | 11 ± 2.3 |

| STAT3 (n = 14) | 41 ± 3.1 | 65 ± 3.8 | 33 ± 3.7 | 1.5 ± 0.29 (n = 11) | 8.7 ± 1.6 (n = 11) |

| TYK2 (n = 2) | 41* | 53 ± 24 | 43 ± 27 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 15 ± 5.4 |

| Controls | 43 ± 1.4 (n = 54) | 39 ± 1.7 (n = 70) | 59 ± 1.7 (n = 70) | 2.8 ± 0.24 (n = 61) | 15 ± 1.1 (n = 61) |

Values are mean ± SEM percentage.

PID indicates primary immunodeficiency.

Analysis was only performed on 1 patient.

Naive CD4+ T cells from patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 are unable to differentiate into IL-21–expressing cells in response to IL-12

To assess the potential of CD4+ T cells deficient for IL-12Rβ1 to differentiate into Tfh-like cells, we examined the ability of naive cells to express IL-21 in vitro. Naive CD4+ T cells were cultured with T-cell activation and expansion beads alone (nil) or with IL-12 (Th1). After 5 days, cells were restimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate/ionomycin, and the expression of IL-21 and IFNγ was then determined. Naive CD4+ T cells from either healthy donors or patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 expressed little IL-21 or IFNγ when cultured under neutral (nil) conditions (Figure 1G-J). However, when normal naive CD4+ T cells were cultured under Th1-polarizing conditions (ie, with IL-12), IL-21– and IFNγ–expressing cells were readily detectable (Figure 1G,I,J). In contrast, IL-12 failed to induce IL-21 or IFNγ in naive CD4+ T cells deficient for IL-12Rβ1 (Figure 1H-J). Next, we questioned whether naive CD4+ T cells deficient for IL-12Rβ1 could differentiate into IL-21–expressing cells in response to other cytokines and signaling pathways. Accordingly, naive CD4+ T cells from healthy donors and patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1 were subjected to Th2 (IL-4) and Th17 (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-21, IL-23) polarizing conditions or were cultured in the presence of IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, or IL-27. A small frequency of IL-21–expressing cells could be generated from both normal and IL-12Rβ1–deficient naive CD4+ T cells activated with IL-21 or IL-27 (Figure 1I). Similarly, although IL-12 could not induce IFNγ in naive CD4+ T cells deficient for IL-12Rβ1, the ability of IL-27 to induce IFNγ was unaffected by IL12RB1 mutations (Figure 1J). Taken together these results indicate that, although IL-12–induced IL-21 expression is abrogated by IL12RB1 mutations, other cytokines and their associated signaling pathways that induce IL-21 (eg, IL-21 and IL-27, albeit to a lesser extent than IL-12) are intact, which is consistent with normal Ab responses to infection and vaccinations in these patients.30,31

Analysis of cytokine responsiveness in STAT-deficient human CD4+ T cells

The cytokines that induce IL-21 in human naive CD4+ T cells (IL-12, IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, IL-27)11,22 function by activating JAK/STAT signaling pathways. These cytokines phosphorylate STAT1 (IL-6, IL-12, IL-21, IL-23, IL-27), STAT3 (IL-6, IL-12, IL-21, IL-23, IL-27), STAT4 (IL-12, IL-23), and STAT5 (IL-12).20,21,24,32–35 We confirmed these studies by showing that these IL-21–inducing cytokines predominantly activate STAT1, STAT3, and STAT4 in human naive CD4+ T cells (data not shown), suggesting that these transcription factors are important in inducing Tfh cells in humans. To investigate this further, we took advantage of additional primary immunodeficiencies that result from mutations in components of several cytokine-signaling pathways, namely STAT1, TYK2, and STAT3.

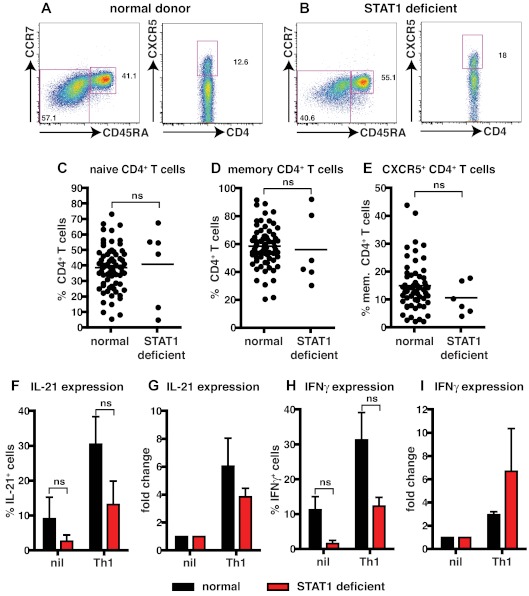

STAT1 is dispensable for IL-12–induced expression of IL-21 in human CD4+ T cells

STAT1-deficient patients and healthy donors had comparable frequencies of naive and memory CD4+ T cells (Figure 2A-D; Table 3). The proportions of CXCR5+CD45RA− or CD45RA+ Tfh cells in STAT1-deficient patients were also comparable with healthy donors (Figure 2A-B,E; Table 3). The ability of STAT1-deficient CD4+ T cells to differentiate into IL-21+ cells in response to Th1-polarizing conditions was then tested. Because of the limited numbers of cells available from these rare patients, total CD4+ T cells were examined. When CD4+ T cells from healthy donors or STAT1-deficient patients were activated under neutral conditions, IL-21 and IFNγ production could be detected; however, the frequencies of cytokine-expressing cells was lower in STAT1-deficient patients (Figure 2F,H; IL-21: normal, 9.1% ± 6.2%; STAT1, 2.7% ± 1.8%; IFNγ: normal, 11.3% ± 3.8%; STAT1, 1.6% ± 0.9%). Despite these differences in the nonpolarizing cultures, expression of IL-21 and IFNγ in both normal and STAT1-deficient CD4+ T cells increased after culture with IL-12 (Figure 2F,H; IL-21: normal, 30.5% ± 7.9%; STAT1, 13.2% ± 6.7%; IFNγ: normal, 31.3% ± 7.9%; STAT1, 12.3% ± 2.5%). Although there appeared to be a reduced ability of IL-12 to enhance expression of IL-21 and IFNγ in the absence of STAT1, compared with normal CD4+ T cells (Figure 2F,H), when the effect of IL-12 was expressed as fold-change relative to nonpolarizing cultures, STAT1-deficient CD4+ T cells responded comparably to normal cells, that is, ∼ 4- to 6-fold increase in IL-21 (Figure 2G) and ∼ 3- to 6-fold induction in IFNγ expression (Figure 2I). Together these results indicate that IL-12–induced IL-21 and IFNγ in CD4+ T cells is independent of STAT1 signaling.

Figure 2.

STAT1 is dispensable for IL-12–induced expression of IL-21 in human CD4+ T cells. (A-E) The frequency of naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), memory (CD45RA+CCR7−/+), and CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells in PBMCs was determined for healthy donors and STAT1-deficient patients. (A-B) Representative dot plots from 1 donor and 1 STAT1-deficient patient. (C-E) The frequency of (C) naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), (D) memory (CD45RA+CCR7−/+), and (E) CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells from all healthy donors (total CD4+ T cells, n = 54; naive CD4+ T cells, n = 70; memory CD4+ T cells, n = 70; CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells, n = 61) and STAT1-deficient patients (n = 6) was examined. (F-I) Total CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy donors and STAT1-deficient patients (n = 3) were cultured for 5 days under neutral (nil) or Th1-polarizing (ie, IL-12) conditions, and expression of intracellular IL-21 (F-G) and IFNγ (H-I) was then determined. The graphs in panels F and H show the frequency of cytokine-positive cells; those in panels G and I depict cytokine expression after Th1 polarization as fold-increase relative to the nil culture in each experiment. The values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

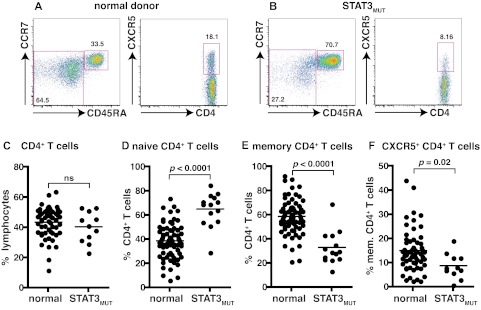

Mutations in STAT3 compromise the generation of CD4+ memory and CXCR5+ Tfh cells

To investigate further the signaling pathways involved in the differentiation of IL-21–expressing cells we used patients with autosomal-dominant hyper IgE syndrome resulting from heterozygous mutations in STAT3.36,37 Patients heterozygous for these mutations display impaired, but not abolished, STAT3 function with ∼ 25% residual signaling.36,37 As detailed above, STAT3 is activated by many cytokines, including those that induce IL-21 expression in human CD4+ T cells (ie, IL-6, IL-12, IL-21, IL-23, IL-27).20,21,24,32–35 The frequency of total CD4+ T cells was comparable between healthy donors and STAT3MUT patients (Figure 3C). Compared with healthy donors, STAT3MUT patients have a significant increase in the frequency of naive and a significant decrease in the frequency of memory CD4+ T cells (Figure 3A-F; Table 3). Analysis of CXCR5+ T cells within the CD45RA+ and CD45RA− fractions revealed significant decreases in both of these compartments in STAT3MUT patients compared with healthy donors (Figure 3A-B,F; Table 3). Thus, mutations in STAT3 cause a ∼ 50% reduction in the frequency of circulating CXCR5+CD45RA− and CD45RA+ Tfh cells (Figure 3F; Table 3).

Figure 3.

Mutations in STAT3 compromise the generation of CD4+ memory and CXCR5+CD45RA− Tfh cells. (A-B) The frequency of naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), memory (CD45RA+CCR7−/+), and CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells in PBMCs was determined for healthy donors and STAT3MUT patients. (A-B) Representative dot plots from 1 donor and 1 patient. (C-F) The frequency of (C) total CD4+ T cells, (D) naive (CD45RA+CCR7+), (E) memory (CD45RA+CCR7−/+), and (F) CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells from all healthy donors (total CD4+ T cells, n = 54; naive CD4+ T cells, n = 70; memory CD4+ T cells, n = 70; CXCR5+CD45RA− CD4+ T cells, n = 61) and STAT3MUT patients (n = 14) was examined.

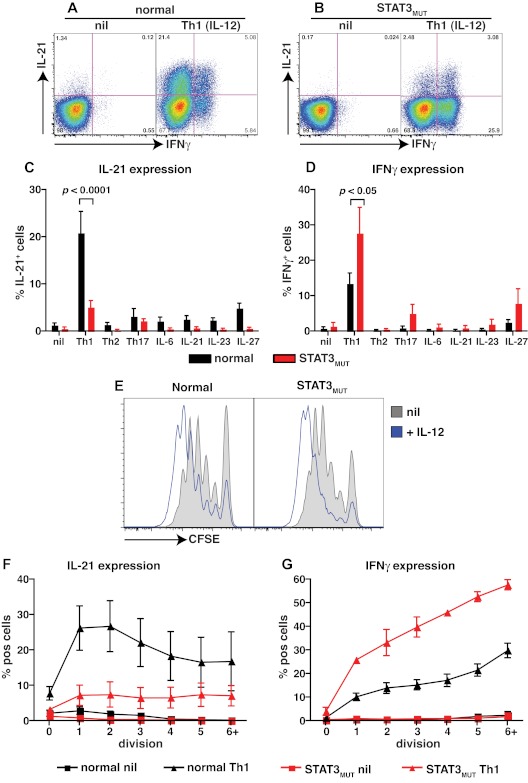

STAT3 mutations partially impairs IL-12–induced expression of IL-21 in naïve CD4+ T cells

The observations that (1) IL-12 is the main driver of human Tfh cell differentiation in vitro,11,22 (2) IL-12 is capable of activating STAT3,21,32–35 and (3) STAT3MUT patients have a contracted population of circulating CD4+ CXCR5+CD45RA− and CD45RA+ Tfh-like cells (Figure 3E) led us to investigate the consequences of STAT3 mutations on the ability of IL-12 to induce IL-21 in human naive CD4+ T cells. No differences were observed in the low frequencies of IL-21– and IFNγ–expressing cells detected in cultures of naive CD4+ T cells from healthy donors or STAT3MUT patients after stimulation under neutral conditions (Figure 4A-D). However, induction of IL-21 expression by IL-12 was significantly reduced in STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells compared with normal naive CD4+ T cells (Figure 4A-C; normal, 20.9% ± 4.5%; STAT3MUT, 5.2% ± 1.3%). In fact this defect was most pronounced when the frequency of IL-21+IFNγ− cells were determined (Figure 4A-B). This analysis found a significant (P < .01) decrease in IL-21+IFNγ− cells but not IL-21+IFNγ+ (P > .05) cells in STAT3MUT patients compared with healthy donors after Th1 polarization (IL-21+IFNγ−: normal, 16.7% ± 3.2%; STAT3MUT, 2.3% ± 0.5%; IL-21+IFNγ+: normal, 4.8% ± 1.5%; STAT3MUT, 3.3% ± 1%). In contrast to IL-21, expression of IFNγ in CD4+ T cells in response to IL-12 was unaffected by STAT3 mutations; in fact it was higher than normal CD4+ T cells (Figure 4D). This increase in IFNγ production by STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells, however, did not contribute to decreased IL-21 production because neutralizing IFNγ in these cultures had no effect on IL-21 expression, and there was a positive correlation between IL-21 and IFNγ expression in both normal and STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells after Th1 polarization (data not shown). It was possible that induction of IL-21 by IL-12 resulted from not only a direct effect of IL-12 but also the effects of other cytokines induced by IL-12 that act in an autocrine manner to further promote IL-21 expression. To address this, we examined IL-21 and IFNγ expression in normal and STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells by qPCR after 24 and 48 hours of stimulation with or without IL-12. Expression of IL21 was substantially increased by IL-12 in normal CD4+ T cells within 24 hours of stimulation, compared with cells cultured under neutral (nil) conditions, and similar levels were detected after 48 hours (supplemental Figure 1A-B, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Consistent with the flow cytometric analysis, expression of IL21 in IL-12–activated STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells was reduced compared with normal controls (supplemental Figure 1A-B). In contrast to IL21, IFNG was abundantly expressed by IL-12–treated STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells; in fact, consistent with the intracellular staining data, IFNG expression by these cells exceeded that of normal naive CD4+ T cells at the 48-hour time point (supplemental Figure 1C-D). These data suggest that IL-12 acts directly to rapidly induce IL-21 expression in naive CD4+ T cells.

Figure 4.

STAT3 mutations impair IL-12–induced expression of IL-21 in naive CD4+ T cells. (A-D) Naive CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy donors (n = 8) and STAT3MUT patients (n = 9) were cultured for 5 days under neutral conditions (nil); polarizing Th1, Th2, or Th17 conditions; or in the presence of IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, or IL-27, after which time expression of intracellular IL-21 and IFNγ was determined. (A-B) Representative dot plots of cytokine expression by activated naive CD4+ T cells from 1 donor and 1 patient. (C-D) Percentage of activated normal and STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells induced to express (C) IL-21 or (D) IFNγ in response to the indicated culture. The values represent the mean ± SEM. (E-F) Naive CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy donors and STAT3MUT patients were labeled with CFSE and cultured with anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 Abs in the absence (nil) or presence of Th1 polarizing conditions (+IL-12). After 5 days cells were harvested, and (E) proliferation and expression of (F) IL-21 and (G) IFNγ in cells that had undergone different divisions were then determined. (F-G) The values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

IL-12 is capable of activating the JAK family protein tyrosine kinase TYK2,38 which subsequently phosphorylates STATs, including STAT3.39 Mutations in TYK2 have been reported in 2 patients who developed susceptibility to various pathogens, including mycobacteria/Bacille Calmette-Guérin and herpes viruses.25,28 One of the contributing factors to disease pathogenesis is believed to be the unresponsiveness of their T cells to IL-12 with respect to induction of IFNγ expression.25 To investigate this further, these 2 patients deficient for TYK2 were examined (supplemental Figure 2). CXCR5+CD45RA− Tfh-like cells were detected in both patients at similar frequencies as healthy donors (supplemental Figure 2A-B,E; Table 3). When IL-21 expression in total CD4+ T cells from 1 patient deficient for TYK2 after culture with IL-12 was examined, the level of induction was ∼ 2-fold less than that observed for normal CD4+ T cells (supplemental Figure 2F-G). We extended these studies by examining naive CD4+ T cells from the second patient deficient for TYK2. Compared with normal naive CD4+ T cells, induction of IL-21 expression by IL-12 in TYK2-deficient CD4+ T cells was severely reduced (supplemental Figure 2I). Induction of IFNγ was also dramatically compromised by TYK2 mutations (supplemental Figure 2H,J). Taken together, these data suggest that mutations in TYK2 and STAT3, which are both activated downstream of the IL-12R,21,32–35,38,39 cause a significant impairment in the ability of naive CD4+ T cells to differentiate into IL-21–expressing cells in response to IL-12.

STAT3 mutations impede division-linked differentiation of CD4+ T cells into IL-21–expressing effector cells

Because IL-12 can promote proliferation of human activated T cells,40 and differentiation of CD4+ T cells into cytokine-expressing cells is linked to cell division,29,41 it was important to determine whether the reduction in expression of IL-21 in IL-12–stimulated STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells resulted from reduced cell division or reflected an intrinsic defect in the differentiation program of these cells.

To do this, we examined proliferation by labeling naive CD4+ T cells with CFSE and tracked their division after in vitro stimulation by monitoring CFSE dilution. There was no difference in cell division between normal or STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells activated under neutral conditions (Figure 4E). Similarly, IL-12 increased proliferation regardless of whether the naive CD4+ T cells were derived from healthy donors or STAT3MUT patients (Figure 4E). When IL-21 expression was examined on a per division basis, we found that it increased in normal CD4+ T cells after the first few divisions and then reached a maximum, being expressed in ∼ 20%-30% of cells after 2-3 divisions (Figure 4F). Expression of IL-21 by STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells also modestly increased with division; however, the frequency of IL-21+ cells in each division never exceeded 10% and thus was dramatically reduced compared with normal CD4+ T cells (Figure 4F). These data establish that the defect in IL-12–induced IL-21 induction in the absence of functional STAT3 was not because of a difference in proliferation, but rather because of an inability to efficiently acquire IL-21 during Tfh cell differentiation. Notably, when IFNγ expression was also analyzed on a per division basis, the frequency of cytokine-positive cells continued to increase with each cell division (Figure 4G). Furthermore, the heightened frequency of IFNγ+ cells observed in STAT3MUT compared with normal CD4+ T cells at the population level (Figure 4D and supplemental Figure 1) was also detected for cells that had undergone different divisions (Figure 4G).

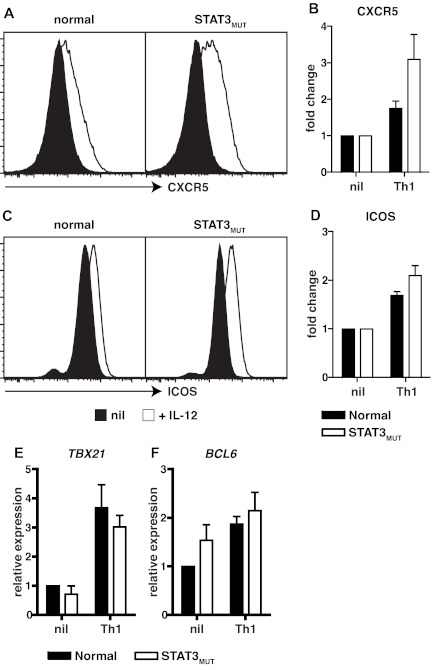

IL-12 can induce additional characteristics of Tfh cells in STAT3 mutant CD4+ T cells

IL-12 not only promotes IL-21 expression in human naive CD4+ T cells but also induces additional features of Tfh cells such as sustained expression of CXCR5 and ICOS, and a modest induction of the Tfh lineage restricted transcription factor BCL6.4,11 We therefore wanted to explore whether the effects of IL-12 on these aspects of CD4+ T-cell activation were also compromised by mutations in STAT3. Compared with naive CD4+ T cells activated under neutral conditions, elevated expression of the Tfh cell markers CXCR5 and ICOS was observed when either normal or STAT3MUT cells were activated in the presence of IL-12 (Figure 5 A,C). In fact, compared with cells cultured under neutral conditions, IL-12 up-regulated CXCR5 and ICOS expressions by 2- to 3-fold on both normal and STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells (Figure 5B,D). IL-12 also up-regulated TBX21 (encoding T-bet) and BCL6, the transcription factors required to generate Th1 and Tfh cells, respectively, to a comparable extent in normal and STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells (Figure 5E,F). Thus, IL-12–mediated induction of CXCR5, ICOS, and BCL6 in Tfh-like cells either only require the residual levels of functional STAT3 that are available in STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells or are STAT3-independent resulting from IL-12–induced activation of STAT4.20,21,34,38 This latter scenario would underlie the normal induction of TBX21 and IFNγ in STAT3MUT Th1 cells.

Figure 5.

Induction of CXCR5, ICOS, and BCL6 by IL-12 in CD4+ T cells is independent of STAT3. (A-D) Naive CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy donors and STAT3MUT patients were cultured with anti-CD2/CD3/CD28 Abs in the absence (nil) or presence of Th1-polarizing conditions (+IL-12). After 4 days the cells were harvested, and surface expression of CXCR5 and ICOS was determined by flow cytometry and of TBX21 and BCL6 by qPCR. (A,C) representative histogram plots from 1 healthy donor and 1 STAT3MUT patient. Expression of (B) CXCR5 (n = 3), (D) ICOS (n = 3), (E) TBX21 (n = 4), and (F) BCL6 (n = 5) after Th1 polarization is presented as fold-increase compared with the nil culture in each experiment. (B,D-F) The graphs represent the mean ± SEM of the indicated number of experiments.

Consistent with our previous findings,11 most of the other culture conditions used in this study (ie, Th2- and Th17-polarizing conditions; exogenous IL-6, IL-21, IL-23) had no effect on expression of CXCR5 and ICOS on normal CD4+ T cells above that observed for the nonpolarizing culture (supplemental Figure 3A-B). However, IL-27 did modestly enhance ICOS expression (supplemental Figure 3B) and induce TBX21 in naive CD4+ T cells (supplemental Figure 3C), and this was independent of STAT3. Interestingly, Th17 polarizing culture conditions induced the greatest levels of BCL6 in naive CD4+ T cells, and this was substantially reduced in STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells (supplemental Figure 3D), reflecting the contribution of STAT3 to the combined signaling of IL-6, IL-21, and IL-23 through their respective receptors.

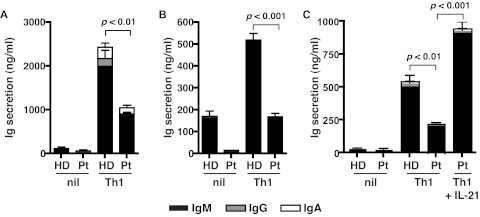

Defective IL-21 production by STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells results in impaired Tfh cell function in vitro

We next questioned whether a reduction in IL-21 expression in STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells would result in a detectable functional defect, such as a compromised ability of these cells to provide help to B cells. To investigate this, we established an in vitro B-cell helper assay in which naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from healthy donors and STAT3MUT patients and activated under neutral or Th1-polarizing conditions. After 5 days, the CD4+ T cells were harvested and cocultured with naive B cells for an additional 7 days, after which time Ig secretion was quantified. Normal naive CD4+ T cells activated under Th1 conditions provided significantly more help to support Ig production by cocultured B cells than when these T cells were cultured under neutral conditions (Figure 6A-C). Although priming under Th1 conditions also increased the helper function of STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells relative to those cultured under neutral conditions, it was significantly less than that of normal CD4+ T cells (Figure 6A-C). This reduction in B-cell help by IL-12–stimulated STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells approximated their reduction in expression of IL-21 under these culture conditions (ie, ∼ 50%-70%; compare Figures 4C and 6A-C), thereby suggesting that the impaired ability of STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells to adequately promote B-cell differentiation resulted from insufficient production of IL-21. Indeed, the reduced ability of IL-12–primed STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells to provide help to B cells could be overcome when IL-21 was added to the cocultures (Figure 6C). Thus, functional STAT3 deficiency compromises the ability of IL-12 to induce IL-21, which is subsequently detrimental to the capacity of these CD4+ T cells to mediate the differentiation of B cells into Ig-secreting cells.

Figure 6.

STAT3-deficient cells show impaired Tfh cell function in vitro. Naive CD4+ T cells isolated from healthy donors (HD) and STAT3MUT patients (Pt) were cultured under neutral (nil) or Th1 polarizing conditions. After 5 days, the cells were harvested and treated with mitomycin C before being cocultured with allogeneic naive B cells, in the absence or presence of exogenous IL-21, for an additional 7 days. After this time secretion of IgM, IgG, and IgA was determined. (A-B) The data were derived from experiments that used naive CD4+ T cells isolated from different STAT3MUT patients; (C) the data show the effect of exogenous IL-21 on the ability of STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells to provide B-cell help. Each graph represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate cultures; similar results were obtained in 5 (A-B) and 2 (C) experiments.

STAT3 mutations abolish IL-21 expression in naive CD4+ T cells induced by IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, and IL-27

As previously shown, other cytokines (IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, IL-27) can also give rise to IL-21–expressing cells, albeit to a much lesser extent than IL-12.11,17,22 When STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells were exposed to these cytokines, they were unable to up-regulate IL-21 expression (Figure 4C). Thus, although mutations in STAT3 substantially reduced the ability of IL-12 to induce IL-21 expression in CD4+ T cells, the ability of IL-6, IL-21, IL-23, and IL-27 to do this was completely dependent on STAT3. Consistent with this, STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells preactivated with IL-6, IL-21, or IL-23 were unable to support Ab production by cocultured B cells (supplemental Figure 3E-F).

Discussion

Lymphocyte differentiation is the outcome of the integration of signals from numerous external stimuli and the activation of specific transcription factors that regulate gene expression and ultimately cellular function. The differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into Th1, Th2, Th17, and T-regulatory cells has been well-characterized for the roles of specific cytokines and transcription factors. The emergence of Tfh cells as the predominant subset of CD4+ T cells that mediate TD humoral immunity has been accompanied by the elucidation of the requirements for their generation and maintenance. Thus, engaging the TCR, ICOS, and the SLAM/SAP pathways by ligands present on APCs, together with signals mediated by STAT3 downstream of receptors for the cytokines IL-6, IL-21, and IL-27, coordinately induce expression of the transcription factors BCL6, IRF4, and c-MAF, which converge to yield Tfh cells.8,12 Despite these generalized findings, much controversy remains over the relative contribution of these individual components to Tfh cell formation; this is most apparent from subsequent studies that have challenged the role of IL-6 and IL-21 in this process.8,12,18,19 Furthermore, the molecular requirements for the generation of human Tfh cells remain incompletely defined.

We and others previously showed that IL-12 plays an important role in the differentiation of human Tfh cells, as evidenced by its ability to induce expression of IL-21 and to maintain expression of ICOS and CXCR5 on naive CD4+ T cells.11,22 Similar to studies in mice,7,14,17 IL-6, IL-21, and IL-27 also induce IL-21 expression in human naive CD4+ T cells, albeit to a much lesser extent than IL-12.11,17,22 We have now substantially extended these findings by investigating the in vivo and in vitro development of Tfh cells in patients with loss-of-function mutations in IL-12RB1, STAT1, TYK2, and STAT3; that is genes that compromise cytokine-mediated intracellular signaling pathways probably involved in regulating human Tfh cell formation.

The specific ability of IL-12 to induce IL-21 expression in human naive CD4+ T cells was confirmed by showing that in the absence of a functional receptor (ie, in patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1) IL-12 was unable to give rise to IL-21–expressing cells (Figure 1I). Interestingly, IL-12–mediated IL-21 expression partially depended on intact STAT3 signaling, because heterozygous mutations in STAT3 (which render most STAT3 dimers nonfunctional) reduced IL-21 expression by 50%-75%. Induction of IL-21 expression in CD4+ T cells by IL-12 was also reduced in the absence of TYK2 but was unaffected by STAT1 deficiency. Further evidence that the generation of human Tfh cells is STAT1 independent was the finding that the frequency of circulating CXCR5+CD45RA− T cells was unaffected by gain-of-function mutations in STAT1 (22% 6.6%; n=3). Although IL-12 is well-characterized for its ability to operate via STAT4-dependent pathways,20 our finding of a requirement for STAT3 in IL-12 function is consistent with numerous studies that have documented STAT3 activation in human and murine T cells exposed to IL-12.21,33,34,38,42 TYK2 is similarly phosphorylated in IL-12–treated T cells.20,38,39 Despite the defect in IL-21 production, IL-12 could still induce STAT3MUT naive CD4+ T cells to acquire other characteristics of Tfh cells such as increased expression of ICOS, CXCR5, and BCL6 (Figure 5A-D). The intact induction of these phenotypic and molecular changes in Tfh-like cells, as well as residual expression of IL-21, in IL-12–treated CD4+ T cells derived from STAT3MUT patients, are probably induced in a STAT4-dependent manner. Thus, IL-12 induces IL-21 expression predominantly through a TYK2/STAT3-dependent mechanism, with a minor contribution via STAT4 signaling. This is supported by the ability of both STAT3 and STAT4 to bind the promoters of the IL21 and BCL6 genes43,44 and also by the recent finding that IL-12 induces IL-21 in murine CD4+ T cells via STAT3- and STAT4-dependent pathways.42 Importantly, the reduction in IL-12–induced expression of IL-21 in STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells translated to a functional defect in TD B-cell differentiation in vitro (Figure 6). Interestingly, although IL-12 could still induce normal levels of ICOS on STAT3MUT CD4+ T cells, this could not compensate for the deficiency in IL-21 production by these T cells, which is the primary source of help for B-cell differentiation. These findings are consistent with a model in which ICOS has a dual role in Tfh cells, first, in their generation from naive precursors, and, second, in enhancing IL-21 expression.12,14,45,46

While the ability of IL-12 to induce IL-21 in naive CD4+ T cells was predominantly STAT3-dependent, induction of IL-21 by IL-6, IL-21, and IL-27; and the ability of CD4+ T cells primed with these cytokines to help B cells, were completely abrogated by mutations in STAT3. Thus, the ability of all cytokines currently identified to induce IL-21 in human CD4+ T cells, and subsequent B cell-helper function would be dramatically affected by STAT3 mutations, that is, either strongly reduced or completely abolished. The importance of intact STAT3 signaling in generating human Tfh cells is reinforced by the significant reduction in the frequencies of circulating CD4+ CXCR5+ T cells in STAT3MUT patients. By contrast, the frequency of these CXCR5+ Tfh-like cells was normal in patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1. This suggests that, although IL-12 induces the greatest frequency of IL-21–expressing CD4+ T cells, there is sufficient redundancy among cytokine signaling pathways involved in generating Tfh cells to overcome the inability of CD4+ T cells to give rise to Tfh cells in the absence of the IL-12 signaling. In other words, IL-6, IL-21, and IL-27 signaling through STAT3 will still give rise to Tfh cells from IL12RB1-mutant CD4+ T cells. This is supported by the observation that humoral immune responses are intact in patients deficient for IL-12Rβ1.26,30,31 Given the critical role of Tfh cells in humoral immune responses, it makes teleologic sense that this level of redundancy evolved to protect against the detrimental effects of Tfh cell deficiency. In contrast, use of STAT3 by several cytokines in the generation of human Tfh cells provides an explanation for why STAT3MUT patients exhibit defects in humoral immune responses (including reductions in circulating CD4+ CXCR5+CD45RA− and CD45RA+ Tfh-like cells, memory B cells and an inability to mount protective Ab responses after vaccination or natural infection24,47,48) that cannot be compensated entirely by IL-12–dependent STAT4 signaling. These clinical, cellular, and serologic features of STAT3 deficiency are reminiscent of patients with mutations in ICOS and CD40LG,49,50 which largely result from an absence of B-cell help by Tfh cells.49,50 Thus, although an intrinsic defect resulting from the inability of B cells to respond to cytokines such as IL-6, IL-10, and IL-21 would contribute to the functional Ab deficiency in STAT3MUT patients,24 this defect would be compounded further by the compromised generation and function of Tfh cells.

Overall, our findings have shed substantial light on the molecular requirements for generating human Tfh cells and have identified a signaling pathway that could be targeted to enhance Tfh cell generation in immunodeficient conditions. The corollary is that because dysregulated activation and/or generation of Tfh cells has been associated with autoimmunity in humans and mice, inhibiting this pathway may represent a novel approach to treating autoAb-mediated conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Garvan Flow Cytometry facility for cell sorting, Dr Rene de Waal Malefyt (DNAX) for providing reagents (IL-4, anti–IL-4 mAb), and the patients and their families for participating in this project.

This work was supported by project and program grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (C.S.M., E.K.D., M.B., D.A.F., M.C.C., and S.G.T.) and Rockefeller University Center for 541 Clinical and Translational science (5UL1RR024143; J.-L.C.). C.S.M. is a recipient of a Career Development Fellowship and S.G.T. is a recipient of a Senior Research Fellowship from the NHMRC of Australia.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.S.M. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript; D.T.A., A.C., and E.K.D performed experiments; J.B., S.B.-D., P.D.A., A.Y.K, D.A., D.E., K.M., S.S.K., Y.M., S.N., M.A.F., S.C., J.M.S., J.P., M.W., P.G., M.C.C., D.A.F., and J.-L.C. provided patient samples and clinical details; M.C.C. also genotyped STAT3-mutant patients; M.B. provided intellectual input; and S.G.T designed the research, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cindy S. Ma, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, 384 Victoria St, Darlinghurst, 2010 NSW, Australia; e-mail: c.ma@garvan.org.au; or Stuart G. Tangye, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, 384 Victoria St, Darlinghurst, 2010 NSW, Australia; e-mail: s.tangye@garvan.org.au.

References

- 1.Tangye SG, Deenick EK, Palendira U, Ma CS. T cell-B cell interactions in primary immunodeficiencies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1250(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192(11):1545–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med. 2000;192(11):1553–1562. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chtanova T, Tangye SG, Newton R, et al. T follicular helper cells express a distinctive transcriptional profile, reflecting their role as non-Th1/Th2 effector cells that provide help for B cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(1):68–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu D, Rao S, Tsai LM, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31(3):457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, Ditoro D, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325(5943):1006–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325(5943):1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deenick EK, Ma CS. The regulation and role of T follicular helper cells in immunity. Immunology. 2011;134(4):361–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma CS, Deenick EK. The role of SAP and SLAM family molecules in the humoral immune response. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1217:32–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasheed A-U, Rahn H-P, Sallusto F, Lipp M, Müller G. Follicular B helper T cell activity is confined to CXCR5(hi)ICOS(hi) CD4 T cells and is independent of CD57 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(7):1892–1903. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma CS, Suryani S, Avery DT, et al. Early commitment of naive human CD4(+) T cells to the T follicular helper (T(FH)) cell lineage is induced by IL-12. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87(8):590–600. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deenick EK, Ma CS, Brink R, Tangye SG. Regulation of T follicular helper cell formation and function by antigen presenting cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23(1):111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogelzang A, McGuire HM, Yu D, Sprent J, Mackay CR, King C. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29(1):127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29(1):138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dienz O, Eaton SM, Bond JP, et al. The induction of antibody production by IL-6 is indirectly mediated by IL-21 produced by CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(1):69–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eddahri F, Denanglaire S, Bureau F, et al. Interleukin-6/STAT3 signaling regulates the ability of naive T cells to acquire B-cell help capacities. Blood. 2009;113(11):2426–2433. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batten M, Ramamoorthi N, Kljavin NM, et al. IL-27 supports germinal center function by enhancing IL-21 production and the function of T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207(13):2895–2906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poholek AC, Hansen K, Hernandez SG, et al. In vivo regulation of Bcl6 and T follicular helper cell development. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):313–326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eto D, Lao C, Ditoro D, et al. IL-21 and IL-6 are critical for different aspects of B cell immunity and redundantly induce optimal follicular helper CD4 T cell (Tfh) differentiation. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard WJ. Cytokines and immunodeficiency diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1(3):200–208. doi: 10.1038/35105066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibbert L, Pflanz S, De Waal Malefyt R, Kastelein RA. IL-27 and IFN-alpha signal via Stat1 and Stat3 and induce T-Bet and IL-12Rbeta2 in naive T cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2003;23(9):513–522. doi: 10.1089/10799900360708632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt N, Morita R, Bourdery L, et al. Human dendritic cells induce the differentiation of interleukin-21-producing T follicular helper-like cells through interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;31(1):158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma CS, Chew GYJ, Simpson N, et al. Deficiency of Th17 cells in hyper IgE syndrome due to mutations in STAT3. J Exp Med. 2008;205(7):1551–1557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avery DT, Deenick EK, Ma CS, et al. B cell-intrinsic signaling through IL-21 receptor and STAT3 is required for establishing long-lived antibody responses in humans. J Exp Med. 2010;207(1):155–171. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Morio T, et al. Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity. 2006;25(5):745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Beaucoudrey L, Samarina A, Bustamante J, et al. Revisiting human IL-12Rbeta1 deficiency: a survey of 141 patients from 30 countries. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89(6):381–402. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181fdd832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woellner C, Gertz EM, Schaffer AA, et al. Mutations in STAT3 and diagnostic guidelines for hyper-IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2):424–432. e428. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilic SS, Hacimustafaoglu M, Boisson-Dupuis S, et al. A patient with tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency without hyper-IgE syndrome [published online ahead of print March 6, 2012]. J Pediatr. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.01.056. doi: 10.1016/j.peds.2012.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma CS, Hare NJ, Nichols KE, et al. Impaired humoral immunity in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease is associated with defective IL-10 production by CD4+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(4):1049–1059. doi: 10.1172/JCI23139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altare F, Durandy A, Lammas D, et al. Impairment of mycobacterial immunity in human interleukin-12 receptor deficiency. Science. 1998;280(5368):1432–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Jong R, Altare F, Haagen IA, et al. Severe mycobacterial and Salmonella infections in interleukin-12 receptor-deficient patients. Science. 1998;280(5368):1435–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, et al. A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002;168(11):5699–5708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gollob JA, Veenstra KG, Jyonouchi H, et al. Impairment of STAT activation by IL-12 in a patient with atypical mycobacterial and staphylococcal infections. J Immunol. 2000;165(7):4120–4126. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.4120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson NG, Szabo SJ, Weber-Nordt RM, et al. Interleukin 12 signaling in T helper type 1 (Th1) cells involves tyrosine phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat)3 and Stat4. J Exp Med. 1995;181(5):1755–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bacon CM, Petricoin EF, III, Ortaldo JR, et al. Interleukin 12 induces tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT4 in human lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(16):7307–7311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Tsuchiya S, et al. Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2007;448(7157):1058–1062. doi: 10.1038/nature06096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1608–1619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacon CM, McVicar DW, Ortaldo JR, Rees RC, O'Shea JJ, Johnston JA. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) induces tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 and TYK2: differential use of Janus family tyrosine kinases by IL-2 and IL-12. J Exp Med. 1995;181(1):399–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watford WT, O'Shea JJ. Human tyk2 kinase deficiency: another primary immunodeficiency syndrome. Immunity. 2006;25(5):695–697. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kubin M, Kamoun M, Trinchieri G. Interleukin 12 synergizes with B7/CD28 interaction in inducing efficient proliferation and cytokine production of human T cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180(1):211–222. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gett AV, Hodgkin PD. Cell division regulates the T cell cytokine repertoire, revealing a mechanism underlying immune class regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(16):9488–9493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakayamada S, Kanno Y, Takahashi H, et al. Early Th1 cell differentiation is marked by a Tfh cell-like transition. Immunity. 2011;35(6):919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei L, Laurence A, Elias KM, O'Shea JJ. IL-21 is produced by Th17 cells and drives IL-17 production in a STAT3-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(48):34605–34610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705100200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei L, Vahedi G, Sun HW, et al. Discrete roles of STAT4 and STAT6 transcription factors in tuning epigenetic modifications and transcription during T helper cell differentiation. Immunity. 2010;32(6):840–851. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akiba H, Takeda K, Kojima Y, et al. The role of ICOS in the CXCR5+ follicular B helper T cell maintenance in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2340–2348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi YS, Kageyama R, Eto D, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 2011;34(6):932–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Speckmann C, Enders A, Woellner C, et al. Reduced memory B cells in patients with hyper IgE syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2008;129(3):448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheerin KA, Buckley RH. Antibody responses to protein, polysaccharide, and phi X174 antigens in the hyperimmunoglobulinemia E (hyper-IgE) syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87(4):803–811. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yong PF, Salzer U, Grimbacher B. The role of costimulation in antibody deficiencies: ICOS and common variable immunodeficiency. Immunol Rev. 2009;229(1):101–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova J-L, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee for Primary Immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2011;2:1–26. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.