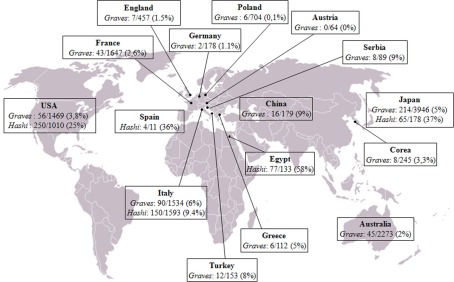

The relationship between cancer and inflammation is well known since 1863 when Rudolf Virchow, following the observation of leukocytes in neoplastic tissues, hypothesized that chronic inflammation could contribute to the tumorigenic process. In the following decades, several lines of evidence suggested a strong association between chronic inflammation and increased susceptibility to neoplastic transformation and cancer development. It was estimated that up to 20% of all tumors arise from conditions of persistent inflammation such as chronic infections or autoimmune diseases. Indeed, the associations are well known between cervical cancer and papilloma virus, gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori induced gastritis, esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett's metaplasia, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatitis B and C viral infections, and many others. Some of the mechanisms forming the basis of the relationship between inflammation and tumor have been recently elucidated. The inflammatory microenvironment of neoplastic tissues is characterized by the presence of host leukocytes both in the supporting stroma and among the tumor cells, with macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, and T cells being differentially distributed (Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001). Several cytokines (TNF, IL-1, IL-6) and chemokines that are produced by the tumor cells and by leukocytes and platelets associated with the tumor have been found to be able to maintain the invasive phenotype (Coussens and Werb, 2002). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are a major component of the leukocyte infiltrate, initially recruited by inflammatory chemokines (e.g., CCL2) and then sustained by cytokines present in the tumor microenvironment (e.g., CSFs, VEGF-A). In response to cytokines such as TGF-β, IL-10, and M-CSF, TAMs promote tumor proliferation and progression and stroma deposition and, indeed, the density of TAMs is increased in advanced thyroid cancers (Ryder et al., 2008). As far as papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) is concerned, this tumor is frequently associated with autoimmune thyroid diseases, Graves’ disease, and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. The frequency of association is extremely variable in the series from different countries, 0–9% for Graves’ and 9–58% for Hashimoto's (Figure 1). It is still debated whether association with an autoimmune disorder could influence the prognosis of PTC. Indeed a worse prognosis was reported in few series (Ozaki et al., 1990; Pellegriti et al., 1998), while the majority of the studies showed either a protective effect of thyroid autoimmunity (Matsubasyashi et al., 1995; Loh et al., 1999; Gupta et al., 2001) or a similar behavior between cancer with and without associated thyroiditis (Yano et al., 2007). These discrepancies can be due to either the low number of patients examined in those studies, the lack of a control group, the existence of different genetic and epidemiological backgrounds, or the use of inappropriate criteria to define remission or persistence/relapse. We recently produced data extending the knowledge about the tight relationships among thyroiditis and thyroid cancer. In particular, the clinical and molecular features, and the expression of inflammation-related genes, were investigated in a large series of PTCs divided in two groups according to the association or not of the tumor with thyroiditis (Muzza et al., 2010). Interestingly, no significant differences between the two groups were found, as far as age at diagnosis, gender distribution, TNM staging, histological variants, and outcome are concerned, suggesting that the association with an autoimmune thyroid process does not modify either the presentation or the clinical behavior of PTC. A crucial finding of the last few years concerns the genetic background of PTCs, since the concept has emerged that the inflammatory protumourigenic microenvironment of this cancer is elicited by the oncogenes responsible for thyroid neoplastic transformation (such as RET/PTC, BRAFV600E, and RASG12V; Borrello et al., 2005, 2008; Melillo et al., 2005; Mantovani et al., 2008). In particular, we recently demonstrated that the RET/PTC1 oncogene activates a transcriptional proinflammatory program in normal human primary thyrocytes (Borrello et al., 2005). Moreover, gene expression studies in cellular systems showed that not only RET/PTC but also RAS and BRAF proteins, all belonging to the RET–PTC/RAS/BRAF/ERK pathway, are able to induce the up-regulation of chemokines, which in turn could contribute to neoplastic proliferation, survival, and migration (Melillo et al., 2005). Consistently, other Authors demonstrated that RET/PTC3-thyrocytes express high levels of proinflammatory cytokines (Russel et al., 2003) and proteins involved in the immune response (Puxeddu et al., 2005). These data are well in agreement with our recent study which firstly showed that PTCs harbor a different genetic background according to the association or not with thyroiditis (Muzza et al., 2010). In particular, RET/PTC was more represented in patients with PTC and autoimmunity, while BRAFV600E was significantly more frequent in patients with PTC alone. Moreover, we showed that the expression of genes encoding three inflammation-related genes (CCL20, CXCL8, and l-selectin) was enhanced either in BRAFV600E or in RET/PTC tumors, compared with normal samples. Interestingly, non-neoplastic tissues with thyroiditis displayed the same levels of expression of CCL20 and CXCL8 compared to normal samples, suggesting that these inflammatory molecules could be associated with tumor-related inflammation, and not with the autoimmune process.

Figure 1.

Worldwide prevalence of papillary thyroid cancer in patients with Graves’ disease (Graves) and Hashimoto's thyroiditis (Hashi), corresponding to the sum of the data reported to date in the literature. References: Australia (Graves: Hales et al., 1992; Barakate et al., 2002); Austria (Graves: Rieger et al., 1989); China (Graves: Chou et al., 1993; Lin et al., 2003); Corea (Graves: Kim et al., 2004); Egypt (Hashimoto: Tamimi, 2002); France (Graves: Melliere et al., 1988; Ozoux et al., 1988; Kraimps et al., 1998; Kraimps, 2000; Mssrouri et al., 2008); Germany (Graves: Wahl et al., 1982); Great Britain (Graves: Hancock et al., 1977); Greece (Graves: Linos et al., 1997); Italy (Graves: Pacini et al., 1988; Belfiore et al., 1990; Miccoli et al., 1996; Pellegriti et al., 1998; Cantalamessa et al., 1999; Zanella et al., 2001; Gabriele et al., 2003; Cappelli et al., 2006; Hashimoto: Fiore et al., 2011); Turkey (Graves: Terzioglu et al., 1993); Japan (Graves: Kasuga et al., 1990; Ozaki et al., 1990; Yano et al., 2007; Hashimoto: Matsubayashi et al., 1995; Ohmori et al., 2007); Poland (Graves: Pomorski et al., 1996); Serbia (Graves: Zivaljević et al., 2008); Spain (Hashimoto: Pino Rivero et al., 2004); USA (Graves: Shapiro et al., 1970; Dobyns et al., 1974; Bradley and Liechty, 1983; Farbota et al., 1985; Behar et al., 1986; Razack et al., 1997; Carnell and Valente, 1998; Weber et al., 2006; Boostrom et al., 2007; Phitayakorn and McHenry, 2008; Hashimoto: Loh et al., 1999; Gupta et al., 2001; Kebebew et al., 2001; Larson et al., 2007).

In conclusion, recent studies opened a new and extremely attractive scenario on the “connection” between thyroid autoimmunity, inflammation, and cancer. The interest is linked not only to the possibility of better understanding the communication between abnormally growing cells and their microenvironment, but also to the chance to pharmacologically interfere with such pro-tumor interactions.

References

- Balkwill F., Mantovani A. (2001). Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357, 539–545 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakate M. S., Agarwal G., Reeve T. S., Barraclough B., Robinson B., Delbridge L. W. (2002). Total thyroidectomy is now the preferred option for the surgical management of Graves’ disease. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 72, 321–324 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2002.02400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar R., Arganini M., Wu T. C., McCormick M., Straus F. H., DeGroot L. J., Kaplan E. L. (1986). Graves'disease and thyroid cancer. Surgery 100, 1121–1127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfiore A., Garofalo M. R., Giuffrida D., Runello F., Filetti S., Fiumara A., Ippolito O., Vigneri R. (1990). Increased aggressiveness of thyroid cancer in patients with Graves’ disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 70, 830–835 10.1210/jcem-70-4-830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boostrom S., Richards M. L. (2007). Total thyroidectomy is the preferred treatment for patients with Graves’ disease and a thyroid nodule. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 136, 278–281 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrello M. G., Alberti L., Ischer A., Degl'innocenti D., Ferrario C., Gariboldi M., Marchesi F., Allavena P., Greco A., Collini P., Pilotti S., Cassinelli G., Bressan P., Fugazzola L., Mantovani A., Pierotti M. A. (2005). Induction of proinflammatory program in normal human thyrocytes by the RET/PTC1 oncogene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14825–14830 10.1073/pnas.0503039102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrello M. G., Degl'Innocenti D., Pierotti M. (2008). Inflammation and cancer: the oncogene-driven connection. Cancer Lett. 267, 262–270 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E. L., Liechty R. D. (1983). Modified subtotal thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease: a two-institution study. Surgery 94, 955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantalamessa L., Baldini M., Orsatti A., Meroni L., Amodei V., Castagnone D. (1999). Thyroid nodules in Graves disease and the risk of thyroid carcinoma. Arch. Intern. Med. 159, 1705–1708 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli C., Braga M., De Martino E., Castellano M., Gandossi E., Agosti B., Cumetti D., Pirola I., Mattanza C., Cherubini L., Agabati Rosei E. (2006). Outcome of patients surgically treated for various forms of hyperthyroidism with differentiated thyroid cancer: experience at an endocrine center in Italy. Surg. Today 36, 125–130 10.1007/s00595-005-3115-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnell N. E., Valente W. A. (1998). Thyroid nodules in Graves’ disease: classification, characterization, and response to treatment. Thyroid 8, 647–652 10.1089/thy.1998.8.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou F. F., Sheen-Chen S. M., Chen Y. S., Chen M. J. (1993). Hyperthyroidism and concurrent thyroid cancer. Int. Surg. 78, 343–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens L. M., Werb Z. (2002). Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420, 860–867 10.1038/nature01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobyns B. M., Sheline G. E., Workman J. B., Tompkins E. A., McConahey W. M., Becker D. V. (1974). Malignant and benign neoplasms of the thyroid in patients treated for hyperthyroidism: a report of the cooperative thyrotoxicosis therapy follow-up study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 38, 976–998 10.1210/jcem-38-6-976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farbota L. M., Calandra D. B., Lawrence A. M., Paloyan E. (1985). Thyroid carcinoma in Graves’ disease. Surgery 98, 1148–1153 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore E., Rago T., Latrofa F., Provenzale M. A., Piaggi P., Delitala A., Scutari M., Basolo F., Di Coscio G., Grasso L., Pinchera A., Vitti P. (2011). Hashimoto's thyroiditis is associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma: role of TSH and of treatment with L-thyroxine. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 18, 429–437 10.1530/ERC-11-0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele R., Letizia C., Borghese M., De Toma G., Celi M., Izzo L., Cavallaro A. (2003). Thyroid cancer in patients with hyperthyroidism. Horm. Res. 60, 79–83 10.1159/000071875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Patel A., Folstad A., Fenton C., Dinauer C. A., Tuttle R. M., Conran R., Francis G. L. (2001). Infiltration of differentiated thyroid carcinoma by proliferating lymphocytes is associated with improved disease-free survival for children and young adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86, 1346–1354 10.1210/jc.86.3.1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales I. B., McElduff A., Crummer P., Clifton-Bligh P., Delbridge L., Hoschl R., Poole A., Reeve T. S., Wilmshurst E., Wiseman J. (1992). Does Graves’ disease or thyrotoxicosis affect the prognosis of thyroid cancer? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 75, 886–889 10.1210/jc.75.3.886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock B. W., Bing R. F., Dirmikis S. M., Munro D. S., Neal F. E. (1977). Thyroid carcinoma and concurrent hyperthyroidism – A study of ten patients. Cancer 39, 298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga Y., Sugenoya A., Kobayashi S., Kaneko G., Masuda H., Fujimori M., Iida F. (1990). Clinical evaluation of the response to surgical treatment of Graves’ disease. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 170, 327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebebew E., Treseler P., Ituarte C. (2001). Coexisting chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and papillary thyroid cancer revisited. World J. Surg. 25, 632–637 10.1007/s002680020165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. B., Han S. M., Kim T. Y., Nam-Goong S., II, Gong G., Lee H. K., Hong S. J., Shong Y. K. (2004). Ultrasonographic screening for detection of thyroid cancer in patients with Graves’ disease. Clin. Endocrinol. 60, 719–725 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraimps J. L., Bouin-Pineau M. H., Maréchaud R., Barbier J. (1998). Graves’ disease and thyroid nodules, a not exceptional association. Ann. Chir. 52, 449–451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraimps J. L., Bouin-Pineau M. H., Mathonnet M., De Calan L., Ronceray J., Visset J., Marechaud R., Barbier J. (2000). Multicentre study of thyroid nodules in patients with Graves’ disease. Br. J. Surg. 87, 764–775 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson S., Jackson L., Riall T., Uchida T., Thomas R., Qiu S., Evers B. (2007). Increased incidence of well-differentiated thyroid cancer associated with Hashimoto thyroiditis and the role of the PI3k/Akt pathway. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 204, 764–775 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H., Chiang F. Y., Wang L. F. (2003). Prevalence of thyroid cancer in hyperthyroidism treated by surgery. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 19, 379–384 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70460-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linos D. A., Karakitsos D., Papademetriou J. (1997). Should the primary treatment of hyperthyroidism be surgical? Eur. J. Surg. 163, 651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh K. C., Greenspan F. S., Dong F., Miller T. R., Yeo P. P. B. (1999). Influence of lymphocytic thyroiditis on the prognostic outcome of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 458–462 10.1210/jc.84.2.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A., Allavena P., Sica A., Balkwill F. (2008). Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 54, 436–444 10.1038/nature07205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubasyashi S., Kawai K., Matsumoto Y., Mukuta T., Morita T., Hirai K., Matsukuza F., Kakudoh K., Kuma K., Tamai H. (1995). The correlation between papillary thyroid carcinoma and lymphocytic infiltration in the thyroid gland. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 80, 3421–3424 10.1210/jc.80.12.3421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melillo R. M., Castellone M. D., Guarino V., De Falco V., Cirafici A., Salvatore G., Caiazzo F., Basolo F., Giannini R., Kruhoffer M., Orntoft T., Fusco A., Santoro M. (2005). The RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF linear signaling cascade mediates the motile and mitogenic phenotype of thyroid cancer cells. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1068–1081 10.1172/JCI22758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Melliere D., Etienne G., Becquemin J. P. (1988). Operation for hyperthyroidism: methods and rationale. Am. J. Surg. 155, 395–399 10.1016/S0002-9610(88)80098-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miccoli P., Vitti P., Rago T., Iacconi P., Bartalena L., Bogazzi F., Fiore E., Valeriano R., Chiovato L., Rocchi R., Pinchera A. (1996). Surgical treatment of Graves’ disease: subtotal or total thyroidectomy? Surgery 120, 1020–1024 10.1016/S0039-6060(96)80049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mssrouri R., Benamr S., Esadel A., Mdaghri J., Mohammadine el H., Lahlou M. K., Taghy A., Belmahi A., Chad B. (2008). Thyroid cancer in patients with Graves’ disease. J. Chir. (Paris) 145, 244–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzza M., Degl'Innocenti D., Colombo C., Perrino M., Ravasi E., Rossi S., Cirello V., Beck-Peccoz P., Borrello M. G., Fugazzola L. (2010). The tight relationship between papillary thyroid cancer, autoimmunity and inflammation: clinical and molecular studies. Clin. Endocrinol. 72, 702–708 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03699.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmori N., Miyakawa M., Ohmori K., Takano K. (2007). Ultrasonographic findings of papillary thyroid carcinoma with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Intern. Med. 46, 547–550 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki O., Ito K., Kobayashi K., Toshima K., Iwasaki H., Yashiro T. (1990). Thyroid carcinoma in Graves’ disease. World J. Surg. 14, 437–440 10.1007/BF01658550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozoux J. P., de Calan L., Portier G., Rivallain B., Favre J. P., Robier A., Goga D., Brizon J. (1988). Surgical treatment of Graves’ disease. Am. J. Surg. 156, 177–181 10.1016/S0002-9610(88)80060-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacini F., Elisei R., Di Coscio G. C., Anelli S., Macchia E., Concetti R., Miccoli P., Arganini M., Pinchera A. (1988). Thyroid carcinoma in thyrotoxic patients treated by surgery. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 11, 107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegriti G., Belfiore A., Giuffrida D., Lupo L., Vigneri R. (1998). Outcome of differentiated thyroid cancer in Graves’ patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 83, 2805–2809 10.1210/jc.83.8.2805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phitayakorn R., McHenry C. R. (2008). Incidental thyroid carcinoma in patients with Graves’ disease. Am. J. Surg. 195, 292–297 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pino Rivero V., Guerra Camacho M., Marcos García M., Trinidad Ruiz G., Pardo Romero G., González Palomino A., Blasco Huelva A. (2004). The incidence of thyroid carcinoma in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Our experience and literature review. An Otorrinolaringol. Ibero Am. 31, 223–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomorski L., Cywiński J., Rybiński K. (1996). Cancer in hyperthyroidism. Neoplasma 43, 217–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puxeddu E., Knauf J. A., Sartor M. A., Castellone M. D., Santoro M., Rothstein J. L. (2005). RET/PTC induced gene expression in thyroid PCCL3 cells reveals early activation of genes involved in regulation of the immune response. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 12, 319–334 10.1677/erc.1.00947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razack M. S., Lore J. M., Lippes H. A., Schaefer D. P., Rassael H. (1997). Total thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease. Head Neck 19, 378–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger R., Pimpl W., Money S., Rettenbacher L., Galvan G. (1989). Hyperthyroidism and concurrent thyroid malignancies. Surgery 106, 6–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russel J. P., Shinoara S., Melillo R. M., Castellone M. D., Santoro M., Rothstein J. L. (2003). Tyrosine kinase oncoprotein, RET/PTC3, indices the secretion of myeloid growth and chemotactic factors. Oncogene 22, 4569–4577 10.1038/sj.onc.1206759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder M., Ghossein R. A., Ricarte-Filho J. C., Knauf J. A., Fagin J. A. (2008). Increased density of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with decreased survival in advanced thyroid cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 15, 1069–1074 10.1677/ERC-08-0036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S. J., Friedman N. B., Perzik S. L., Catz B. (1970). Incidence of thyroid carcinoma in Graves’ disease. Cancer 26, 1261–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi D. M. (2002). The association between chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis and thyroid tumors. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 10, 14–16 10.1177/106689690201000207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzioğlu T., Tezelman S., Onaran Y., Tanakol R. (1993). Concurrent hyperthyroidism and thyroid carcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 80, 1301–1302 10.1002/bjs.1800801027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl R. A., Goretzki P., Meybier H., Nitschke J., Linder M., Röher H. D. (1982). Coexistence of hyperthyroidism and thyroid cancer. World J. Surg. 6, 385–390 10.1007/BF01657662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K. J., Solorzano C. C., Lee J. K., Gaffud M. J., Prinz R. A. (2006). Thyroidectomy remains an effective treatment option for Graves’ disease. Am. J. Surg. 191, 400–405 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano Y., Shibuya H., Kitagawa W., Nagahama M., Sugino K., Ito K., Ito K. (2007). Recent outcome of Graves’ disease patients with papillary thyroid cancer. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 157, 325–329 10.1530/EJE-07-0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanella E., Rulli F., Sianesi M., Sciacchitano S., Danese D., Pontecorvi A., Farinon A. M. (2001). Hyperthyroidism with concurrent thyroid cancer. Ann. Ital. Chir. 72, 293–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivaljević V. R., Diklić A. D., Krović K. L., Zorić G. V., Zivić R. V., Kalezić N. K., Kazić M. T., Tatić S. B., Havelka M. J., Paunović I. R. (2008). The incidence rate of thyroid microcarcinoma during surgery benign disease. Acta Chir. Iuglos. 55, 69–73 10.2298/ACI0804069V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]