Abstract

The Elongin complex was originally identified as a positive regulator of RNA polymerase II and is composed of a transcriptionally active subunit (A) and two regulatory subunits (B and C). The Elongin BC complex enhances the transcriptional activity of Elongin A. “Classical” SOCS box-containing proteins interact with the Elongin BC complex and have ubiquitin ligase activity. They also interact with the scaffold protein Cullin (Cul) and the RING domain protein Rbx and thereby are members of the Cullin RING ligase (CRL) superfamily. The Elongin BC complex acts as an adaptor connecting Cul and SOCS box proteins. Recently, it was demonstrated that classical SOCS box proteins can be further divided into two groups, Cul2- and Cul5-type proteins. The classical SOCS box-containing protein pVHL is now classified as a Cul2-type protein. The Elongin BC complex containing CRL family is now considered two distinct protein assemblies, which play an important role in regulating a variety of cellular processes such as tumorigenesis, signal transduction, cell motility, and differentiation.

Keywords: ubiquitin, Cullin, Elongin, ECS complex, SCF complex

Introduction

Polyubiquitin-mediated protein degradation plays an important role in the elimination of short-lived regulatory proteins (Peters, 1998), including those that contribute to the cell cycle, cellular signaling in response to environmental stress or extracellular ligands, morphogenesis, secretion, DNA repair, and organelle biogenesis (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998). The system responsible for the attachment of ubiquitin to the target protein consists of several components that act in concert (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1992; Scheffner et al., 1995), including a ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), and a ubiquitin–protein isopeptide ligase (E3). E3 is believed to be the component of the ubiquitin conjugation system that is most directly responsible for substrate recognition (Scheffner et al., 1995). Based on structural similarity, E3 enzymes have been classified into three families: the HECT (homologous to E6-AP COOH terminus) family (Huibregtse et al., 1995; Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998), the RING finger-containing protein family (Lorick et al., 1999; Freemont, 2000; Joazeiro and Weissman, 2000), and the U box family (Aravind and Koonin, 2000; Hatakeyama et al., 2001; Cyr et al., 2002). The S phase kinase-associated protein 1 (Skp1)–Cullin 1 (Cul1)–F box protein (SCF) family is a member of the RING finger-containing ubiquitin ligase family (Lipkowitz and Weissman, 2011). Cul1 is a scaffold protein and assembles multiple proteins into complexes, which include a small RING finger protein (Rbx1), an adaptor protein (Skp1), and a substrate-targeting protein (F box protein). Substrate recognition by the RING finger-containing ubiquitin ligase family is modulated by post-translational modifications of the target substrate, including phosphorylation, glycosylation, and sumoylation (Lipkowitz and Weissman, 2011). One substrate can be polyubiquitinated by different ubiquitin ligases and vice versa. The Elongin B and C–Cul2 or Cul5–SOCS box protein (ECS) family also belongs to the Cullin RING ligase (CRL) superfamily (Kile et al., 2002). SCF and ECS ubiquitin ligases have structural similarities in that both contain Rbx1 or Rbx2 as a RING finger protein and Cul1, Cul2, or Cul5 as a scaffold protein (Kile et al., 2002; Kamura et al., 2004). Although Skp1 is used as an adaptor protein in the SCF complex, the Elongin B and C complex is used as an adaptor in the ECS complex. Here, we review the Cul2- or Cul5-containing ECS ubiquitin ligase family, about which, compared to SCF ubiquitin ligases, relatively little is known.

The Elongin Complex

The Elongin complex is a positive regulator of RNA polymerase II (pol II) and increases the rate of elongation by suppressing transient pausing along the DNA template (Bradsher et al., 1993a,b). The Elongin complex is composed of a transcriptionally active A subunit and two regulatory subunits, B and C (Garrett et al., 1994, 1995; Aso et al., 1995). Elongin B and C form the Elongin BC complex, which enhances the transcriptional activity of Elongin A. Since Elongin B and C partially resemble ubiquitin and Skp1 (an adaptor of SCF-type ubiquitin ligases), respectively (Bai et al., 1996), they are able to serve as components of protein complexes with functions other than transcriptional regulation. For example, they were found to be components of the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor complex, which is also known as the ECS complex (Figure 1; Duan et al., 1995; Kibel et al., 1995).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the structures of SCF- and ECS-type ubiquitin ligases. (A) SCF-type ubiquitin ligases. Cul1 is used as a scaffold protein and Skp1 bridges the gap between the F box protein and Cul1. (B) Cul2-type ubiquitin ligases. Cul2 is used as a scaffold protein and the Elongin BC complex connects the VHL box protein to Cul2. The Cul2 box determines the use of Cul2 as the scaffold protein. (C) Cul5-type ubiquitin ligases. Cul5 is used as a scaffold protein. Note that the Rbx2 is used for the recruitment of E2 enzyme.

Cul2-Type Ubiquitin Ligase

CRL2pVHL complex

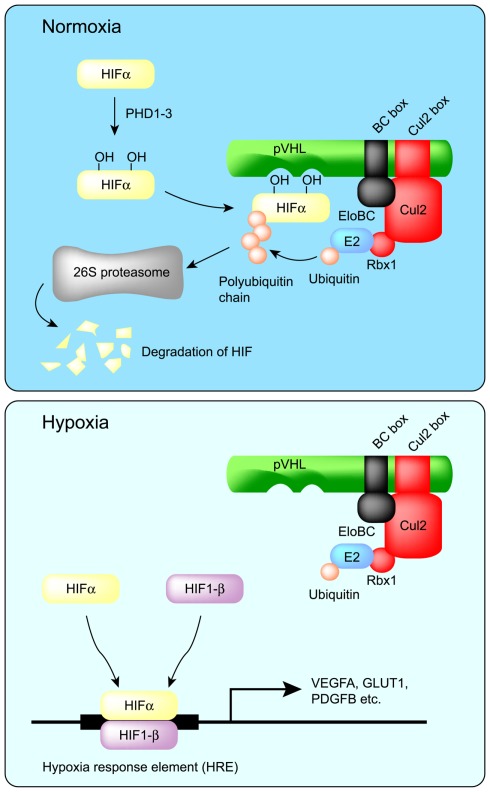

von Hippel–Lindau disease is a hereditary cancer syndrome caused by germline mutations in the VHL tumor suppressor gene (Latif et al., 1993). pVHL is the protein product of the VHL tumor suppressor gene and can bind to the Elongin BC complex. Elongin A and pVHL share a conserved Elongin C-binding sequence motif (S,T,P)LXXX(C,S,A)XXXΦ, which is referred to as the BC box (Conaway et al., 1998; Mahrour et al., 2008). More than 70% of VHL disease and sporadic clear cell renal carcinomas are caused by mutation or deletion of the BC box, which reduces binding affinity to the Elongin BC complex (Duan et al., 1995; Kishida et al., 1995). Approximately 57% of sporadic clear cell renal carcinomas contain inactivating mutations of VHL, of which 98% are caused by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the VHL locus (Gnarra et al., 1994). Epigenetic silencing of VHL by DNA methylation is also involved in the inactivation of VHL (Herman et al., 1996). Although pVHL inhibits the transcriptional activity of Elongin A by competing for binding sites on the Elongin BC complex (Duan et al., 1995), this review will focus on its ubiquitin ligase activity rather than its affect on Elongin-mediated transcription. In addition to the Elongin BC complex, the VHL complex also contains Cul2 and Rbx1 and is similar to SCF (Skp1–Cul1–F box protein) type ubiquitin ligases (Figure 1; Kibel et al., 1995; Pause et al., 1997; Kamura et al., 1999). In fact, the VHL complex has ubiquitin ligase activity and targets the hypoxia-inducible factor-α (HIF-α) family of transcription factors (HIF-1–3α) for proteasomal degradation (Figure 2; Maxwell et al., 1999). At normal oxygen levels, proline residues of the LXXLAP sequence motif within the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD) of HIF-α are hydroxylated and recognized by pVHL (Ivan et al., 2001; Jaakkola et al., 2001; Masson et al., 2001; Hon et al., 2002). As a result, HIF-α is polyubiquitinated and degraded. Three HIF prolyl hydroxylases (PHD1–3) have been identified in mammals and shown to hydroxylate HIF-α subunits (Epstein et al., 2001). Since PHD2 is a critical enzyme for the hydroxylation of HIF-1α, PHD1, and 3 may hydroxylate other target substrates (Berra et al., 2003). In low oxygen conditions, PHDs are unable to hydroxylate the HIF-α subunits, which are therefore not recognized and targeted for degradation by pVHL. The unhydroxylated HIF-α dimerizes with constitutively expressed HIF-1β, also called aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), and translocates to the nucleus, where it induces the transcription of downstream target genes, including vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), solute carrier family 2 member 1 (SLC2A1, which encodes GLUT1), and platelet-derived growth factor-β (PDGFB; Kourembanas et al., 1990; Wizigmann-Voos et al., 1995; Gnarra et al., 1996; Iliopoulos et al., 1996; Maxwell et al., 1999). Loss of functional pVHL protein prevents the O2-dependent degradation of HIF-α, resulting in constitutive expression of HIF-dependent genes and consequently VHL disease.

Figure 2.

Regulation of HIF-α protein by pVHL. In normoxia, two proline residues of HIF-α are hydroxylated by PHD1–3, and then HIF-α is recognized by pVHL for polyubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. On the other hand, in hypoxia, HIF-α escapes prolyl hydroxylation and thereby escapes degradation. HIF-α then dimerizes with HIF-1β to form an active transcription complex. Prolonged activation of the HIFα/β transcription complex is a major contributor to VHL disease.

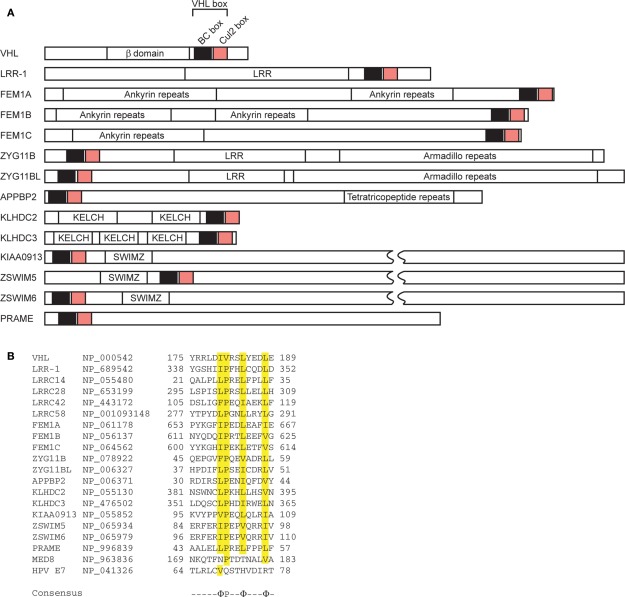

The pVHL protein contains the recently defined “VHL box,” which is composed of a BC box and a Cul2 box (Figure 3; Kamura et al., 2004). The Cul2 box specifically recognizes the endogenous Cul2/Rbx1 complex in a similar manner to SCF-type ubiquitin ligase recognition by F box and Skp1 (Figure 1; Kamura et al., 2004). The ring finger protein Rbx1 recruits ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and is an essential molecule for the formation of SCF-type and Cul2-type ubiquitin ligases (Kamura et al., 1999, 2004; Ohta et al., 1999; Seol et al., 1999; Skowyra et al., 1999; Tan et al., 1999). Further study demonstrated that the Cul2 box is located 8–23 amino acids C-terminal to the BC box and has the consensus sequence ΦPXXΦXXXΦ, where the first position is most frequently a leucine (Mahrour et al., 2008). The Cul2 box is therefore partially similar to the Cul5 box.

Figure 3.

Domain organization of VHL box proteins. (A) The VHL box consists of a BC box and a Cul2 box in the order indicated. LRR, leucine-rich repeats; SWIMZ, SWI2/SNF2 MuDR zinc fingers. (B) Alignment of amino acid sequences of selected Cul2 boxes. Identical amino acids are highlighted in yellow. GenBank™ accession numbers of each protein are indicated. The consensus sequence is indicated below. Φ, hydrophobic residue.

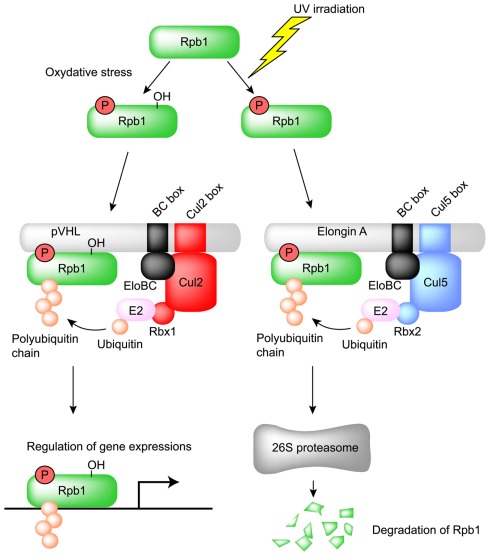

pVHL also polyubiquitinates and induces the degradation of Sprouty2 (Spry2), which is implicated in the growth and progression of tumors (Anderson et al., 2011). Proline residues of Spry2 are hydroxylated by PHD at normoxia and are recognized by pVHL for polyubiquitination and degradation (Anderson et al., 2011). Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is also targeted by pVHL for polyubiquitination and degradation (Zhou and Yang, 2011). pVHL is proposed to down-regulate tumor growth caused by prolonged signaling of activated EGFR (Zhou and Yang, 2011). pVHL also mediates the polyubiquitination of the atypical PKCs, PKCλ, and PKCζII (Okuda et al., 2001; Iturrioz and Parker, 2007). PKCζII interacts with Par6, which plays a critical role in the development of tight junction structures and apico-basal polarization. It also inhibits tight junction formation and thereby plays a regulatory role in the development and transformation of cell polarity (Suzuki et al., 2001; Parkinson et al., 2004). PKCλ may have a similar function, which is also inhibited by pVHL through ubiquitin-dependent degradation. pVHL also polyubiquitinates the seventh subunit of human RNA polymerase II (hsRPB7) and suppresses hsRPB7-dependent VEGF promoter transactivation, VEGF mRNA expression, and VEGF protein secretion (Na et al., 2003). The large subunit of RNA polymerase II (Rpb1), which has sequence and structural similarity to the pVHL-binding domain of HIF-1α, is bound and polyubiquitinated by pVHL (Figure 4; Kuznetsova et al., 2003). The interaction between pVHL and Rpb1 is enhanced by hyperphosphorylation of Rpb1 by UV radiation, which indicates that Rpb1 ubiquitination may have a role in transcription-coupled DNA repair (Figure 4; Svejstrup, 2002; Kuznetsova et al., 2003). Further study showed that proline 1465 of Rpb1, which is located within the LXXLAP motif, is hydroxylated mainly by PHD1 during oxidative stress (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). pVHL is necessary for the oxidative stress-dependent hydroxylation of Pro1465, the phosphorylation of Ser5, and the polyubiquitination of Rpb1 and its recruitment to the DNA (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). Surprisingly, in renal clear cell carcinoma (RCC), pVHL increased the protein abundance and non-degradative ubiquitination of Rpb1 (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). Polyubiquitination of Rpb1 in RCC cells by pVHL contributes to tumor growth by modulating gene expression (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). This is different from previous results found in PC12 cells, in which pVHL polyubiquitinates Rpb1 for protein degradation (Kuznetsova et al., 2003). How pVHL differentially regulates Rpb1 in cells of different origins awaits further investigation.

Figure 4.

Regulation of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II (Rpb1) by pVHL and Elongin A. Ser5 and Pro1465 of Rpb1 are phosphorylated and hydroxylated, respectively, by oxidative stress and then recognized by the Cul2-type ubiquitin ligase pVHL. The resulting polyubiquitinated Rpb1 is not degraded by proteasome and contributes to tumor growth by modulating gene expression in renal clear cell carcinoma. Ser5 of Rpb1 is also phosphorylated by UV irradiation and recognized by the Cul5-type ubiquitin ligase Elongin A for proteasomal degradation.

CRL2LRR-1 complex

Leucine-rich repeat protein (LRR)-1 contains a VHL box and physiologically interacts with the endogenous Cul2–Rbx1 complex (Figure 3; Kamura et al., 2004; Costessi et al., 2011). In fact, nematode LRR-1 degrades the Cip/Kip CDK-inhibitor CKI-1 in C. elegans to promote cell cycle progression in germ cells (Starostina et al., 2010). Human LRR-1 also polyubiquitinates the CDK-inhibitor p21Cip1; however, it does not affect cell cycle progression (Starostina et al., 2010). Rather, human LRR-1 targets cytoplasmic p21 for degradation to prevent the inhibition of the Rho/ROCK/LIMK pathway (Starostina et al., 2010). These data indicate that human LRR-1 is a negative regulator of cofilin, an actin-depolymerizing protein that decreases cell motility (Starostina et al., 2010).

CRL2FEM1B complex

Feminization-1 (FEM-1) also contains a VHL box and physiologically interacts with endogenous Cul2–Rbx1 complex (Figure 3). FEM-1 regulates apoptosis during the sex determination pathway of the nematode (Hodgkin et al., 1985). In C. elegans, FEM-1 interacts with CED-4, an Apaf-1 homolog, to promote apoptosis, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role in apoptosis regulation (Chan et al., 2000). Nematode FEM-1 polyubiquitinates TRA-1, a Gli-family transcription factor and terminal effector of the sex determination pathway (Starostina et al., 2007). Mouse FEM-1 homolog B (FEM1B) interacts with and polyubiquitinates ankyrin repeat domain 37 (Ankrd37), which contains ankyrin repeats and a putative nuclear localization signal (NLS; Shi et al., 2011). Ankrd37 is highly enriched in mouse testis and is conserved from zebrafish to humans (Shi et al., 2011). These data indicate that the terminal step in sex determination is controlled by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis.

Feminization-1 is polyubiquitinated by SEL-10, an F box and WD40 repeat protein, for proteasomal degradation (Jager et al., 2004). In mammalian cells, receptor for activated C kinase (RACK)1, also a WD40 repeat protein, associates with FEM1B and mediates the polyubiquitination and downregulation of FEM1B (Subauste et al., 2009). RACK1 also binds to the Elongin BC complex and promotes the ubiquitination of HIF-1α independently of the pVHL complex (Liu et al., 2007). Since the Elongin BC binding site in RACK1 is similar to that of pVHL, it has been suggested that RACK1 is a Cul2-type ubiquitin ligase (Liu et al., 2007).

CRL2PRAME complex

Preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma (PRAME) contains a VHL box and physiologically interacts with endogenous Cul2–Rbx1 complex (Kamura et al., 2004; Costessi et al., 2011). Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that PRAME is specifically enriched at enhancers and at transcriptionally active promoters that are also bound by nuclear transcription factor Y (NFY), a transcription factor essential for early embryonic development (Bhattacharya et al., 2003; Costessi et al., 2011). However, the physiological substrates of PRAME have not yet been identified.

Cul5-Type Ubiquitin Ligase

CRL5Cis/SOCS complex

This family consists of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins and cytokine-inducible Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-containing protein (CIS, also known as CISH), which also interacts with the Elongin BC complex through its SOCS box (Piessevaux et al., 2008). To date, eight CIS/SOCS family proteins have been identified: CIS, SOCS1, SOCS2, SOCS3, SOCS4, SOCS5, SOCS6, and SOCS7. All of them have a central SH2 domain as well as a C-terminally located SOCS box consisting of a 40-amino acid motif (Figure 5; Endo et al., 1997; Naka et al., 1997; Starr et al., 1997). Members of the CIS/SOCS family bind to janus kinases (JAKs), certain cytokine receptors, or signaling molecules, thereby suppressing downstream signaling events (Piessevaux et al., 2008). A small kinase inhibitory region (KIR) of SOCS1 and SOCS3 inhibits the JAKs by acting as a pseudo-substrate, resulting in the downregulation of further signal transduction (Piessevaux et al., 2008). The CIS/SOCS family can also down-regulate signaling by competing with downstream molecules for binding to the activated receptors (Ram and Waxman, 1999; Piessevaux et al., 2008) and can prevent signaling by polyubiquitination and degradation of target substrates. For example, SOCS1 polyubiquitinates JAK2, Vav, IRS1, and IRS2 (De Sepulveda et al., 2000; Kamizono et al., 2001; Rui et al., 2002). Recent studies also demonstrated that SOCS1 and SOCS3 are important regulators of adaptive immunity (Kile et al., 2002; Tamiya et al., 2011). Some SOCS box-containing proteins – for example, CIS, SOCS1–7, SPRY domain-containing SOCS box proteins (SSB1, SSB2, and SSB4, also known as SPSB1, 2, and 4, respectively), ras-related protein Rab-40C (also known as RAR3), WD40 repeat-containing SOCS box protein WSB1, leucine-rich repeat protein MUF1, and ankyrin repeat- and SOCS box-containing protein (ASB)11 – also contain a BC box and a Cul5 box inside the SOCS box (Figure 5; Hilton et al., 1998; Kamura et al., 2001, 2004; Babon et al., 2009; Sartori da Silva et al., 2010). The amino acid sequence LPΦP in the Cul5 box results in a specific interaction with Cul5, particularly when there is a proline in the fourth position of the motif (Kamura et al., 2004). Furthermore, endogenous Cul5 interacts with endogenous Rbx2, enabling SOCS box-containing proteins to form a protein complex with Cul5 and Rbx2 (Figure 1C; Kamura et al., 1999, 2004; Ohta et al., 1999). The selective interactions between Cul2 and Rbx1 or Cul5 and Rbx2 suggest that Rbx1 and Rbx2 are functionally distinct, at least in terms of their specific binding to Cullin family members. Although SOCS1 contains a Cul5 box, no interaction between SOCS1 and Cul5 has been detected, most likely because the Cul5 box is incompletely conserved (Kamura et al., 2004). Since SOCS1 polyubiquitinates JAK2, Vav, IRS1, and IRS2 (De Sepulveda et al., 2000; Kamizono et al., 2001; Rui et al., 2002), it is possible that the interaction of SOCS1 with these substrates recruits other ubiquitin ligase(s) that actually mediate their polyubiquitination and degradation, or that SOCS1 binds to the Cul5–Rbx2 module too weakly to have been previously detected (Kamura et al., 2004). Recently, it was reported that SOCS1 and SOCS3 bind more weakly to Cul5, with affinities of 100- and 10-fold lower, respectively, than to the rest of the family (Babon et al., 2009). In general, micromolar affinities are common in physiological interactions, and SOCS1 and SOCS3 have 1 and 0.1 μM affinities, respectively, for Cul5 (Babon et al., 2009). Therefore it is possible that all CIS/SOCS family members can act as ubiquitin ligases. This may explain why only SOCS1 and SOCS3 have been shown to suppress signaling using both SOCS box-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Babon et al., 2009).

Figure 5.

Domain organization of SOCS box proteins. (A) The SOCS box consists of a BC box and a Cul5 box in the order indicated. SH2, Src homology 2 phosphotyrosine binding domain; WD40, WD40 repeats; SPRY, sp1A/ryanodine receptor domain; Ank, ankyrin repeats; LRR, leucine-rich repeats; GTPase, GTPase domain. (B) Alignment of amino acid sequences of selected Cul5 boxes. Identical amino acids are highlighted in yellow. GenBank™ accession numbers of each protein are indicated. The consensus sequence is indicated below. Φ, hydrophobic residue.

CRL5Elongin A complex

pVHL is a ubiquitin ligase for the large subunit of RNA polymerase II (Rpb1), as mentioned above. Interestingly, ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Rpb1 following UV irradiation are significantly suppressed in Elongin A-deficient cells, which suggests that Elongin A is also a ubiquitin ligase for Rpb1 (Yasukawa et al., 2008). In fact, polyubiquitination and degradation are rescued by the transfection of wild-type Elongin A (Yasukawa et al., 2008). Furthermore, Elongin A and the Elongin BC complex can associate with Cul5 and Rbx2, and this complex efficiently polyubiquitinates Rpb1 in vitro (Yasukawa et al., 2008). Phosphorylation of Rpb1 at Ser5 after UV irradiation significantly enhanced the interaction between Elongin A and Rpb1 (Yasukawa et al., 2008). These data indicate that Elongin A, like pVHL, is involved in the ubiquitination and degradation of Rpb1 following DNA damage (Figure 4).

CRL5SSB complex

Inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase (iNOS, NOS2) is a high-output NOS compared with NOS1 and NOS3. The activity of iNOS is approximately 10-fold greater than that of NOS1 and NOS3 (Lowenstein and Padalko, 2004). iNOS is not expressed under normal conditions but is induced in response to cytokines, microbes, or microbial products, resulting in the sustained production of NO (Lowenstein and Padalko, 2004). As a result, reactive nitrogen intermediates (such as NO, nitrite, and nitrate) and the products of the interaction of NO with reactive oxygen species (such as peroxynitrite and peroxynitrous acid) are accumulated and used to inhibit viruses or bacteria (Fang, 1997; Nathan and Shiloh, 2000; Lowenstein and Padalko, 2004). SSB1, 2 and 4 polyubiquitinate iNOS for proteasomal degradation (Kuang et al., 2010; Nishiya et al., 2011). SSB2-deficient macrophages showed prolonged iNOS and NO production, resulting in the enhanced killing of L. major parasites (Kuang et al., 2010). Further study showed that SSB1 and SSB4 are major ubiquitin ligases for iNOS and prevent the overproduction of NO, which could cause cytotoxicity (Nishiya et al., 2011).

CRL5WSB1 complex

WSB1 polyubiquitinates homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2), which is a nuclear protein kinase and is well-conserved from Drosophila to humans (Choi et al., 2005, 2008). HIPK2 interacts with a variety of transcription factors (D’Orazi et al., 2002; Hofmann et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006), the p300/CBP co-activator (Kim et al., 2002; Aikawa et al., 2006), and the Groucho/TLE co-repressor (Choi et al., 2005). The loss of HIPK2 reduces apoptosis and increases the numbers of trigeminal ganglia, while the overexpression of HIPK2 in the developing sensory and sympathetic neurons promotes apoptosis in a caspase-dependent manner (Doxakis et al., 2004; Wiggins et al., 2004). HIPK2 plays an important role in apoptosis mediated by p53, CtBP, Axin, Brn3, Sp100, TP53INP1, and PML (Moller et al., 2003a,b; Tomasini et al., 2003; Doxakis et al., 2004; Kanei-Ishii et al., 2004). UV irradiation activates and stabilizes HIPK2, most likely by WSB1-independent auto-phosphorylation, which results in the phosphorylation of p53 at Ser46. Expression of p53 target genes then promotes apoptosis (D’Orazi et al., 2002; Hofmann et al., 2002). Genotoxic stresses, such as adriamycin and cisplatin, also inhibit polyubiquitination of HIPK2 by WSB1 (Choi et al., 2008). HIPK2 also phosphorylates CtBP at Ser422 and phosphorylated CtBP is degraded via the 26S proteasome, resulting in apoptosis in p53-deficient cells (Zhang et al., 2003). WSB1 expression is induced by Sonic hedgehog (Shh) in developing limb buds and other embryonic structures (Vasiliauskas et al., 1999). WSB1 also ubiquitinates the thyroid hormone-activating enzyme type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase (D2; Dentice et al., 2005). Ubiquitination of Shh-induced D2 by WSB1 induces parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP), thereby regulating chondrocyte differentiation (Dentice et al., 2005). In addition to HIPK2 and D2, WSB1 also binds to the interleukin-21 receptor (IL-21R; Nara et al., 2011). However, instead of promoting its degradation, WSB1 inhibits the degradation of the mature form of IL-21R (Nara et al., 2011). WSB1 associates with the intracytoplasmic region of IL-21R and enhances the maturation of IL-21R from an N-linked glycosylated form to a fully glycosylated mature form (Nara et al., 2011). These data indicate that WSB1 has important roles in both the maturation and the degradation of IL-21R.

CRL5ASB complex

ASB2, 3, 4, 6, 9, and 11 can all bind to Cul5–Rbx2 and form ubiquitin ligase complexes. Retinoic acid induces ASB2 in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells (Guibal et al., 2002). ASB2 targets the actin-binding proteins filamin A and B for proteasomal degradation (Heuze et al., 2008). Since knockdown of endogenous ASB2 in leukemia cells delays retinoic acid-induced differentiation and filamin degradation, ASB2 may regulate hematopoietic cell differentiation by targeting filamins for degradation and thereby modulating actin remodeling (Heuze et al., 2008). ASB2 and Skp2 associate with each other to bridge the formation of a non-canonical cullin1- and cullin5-containing dimeric ubiquitin ligase complex and promote the polyubiquitination and degradation of Jak3 (Nie et al., 2011; Wu and Sun, 2011).

Tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2 (TNF-R2) is polyubiquitinated by ASB3 for proteasomal degradation (Chung et al., 2005). ASB3 can affect T cell signaling by degrading TNF-R2, resulting in the inhibition of downstream signaling events in response to TNF-α (Chung et al., 2005).

Insulin receptor substrate 4 (IRS4) is an adaptor molecule involved in signal transduction by both insulin and leptin, and is widely expressed throughout the hypothalamus, with the greatest expression observed in the medial preoptic nucleus, ventromedial hypothalamus, and arcuate nucleus (Numan and Russell, 1999). ASB4 co-localizes and interacts with IRS4 in hypothalamic neurons (Li et al., 2011). ASB4 polyubiquitinates IRS4 for degradation and decreases insulin signaling (Li et al., 2011).

ASB6 is expressed in 3T3-L1 adipocytes but not in fibroblasts (Wilcox et al., 2004). ASB6 may regulate components of the insulin signaling pathway in adipocytes by promoting the degradation of adapter protein with a pleckstrin homology and SH2 domain (APS; Wilcox et al., 2004).

ASB9 polyubiquitinates creatine kinase B (CKB) and decreases total CKB levels (Debrincat et al., 2007).

The notch signaling pathway is essential for the spatio-temporal regulation of cell fate (Mumm and Kopan, 2000; Lai, 2004; Louvi and Artavanis-Tsakonas, 2006). The single-pass transmembrane protein delta acts as a ligand for the notch receptor. Danio rerio Asb11 (d-Asb11) regulates compartment size in the endodermal and neuronal lineages via the ubiquitination and degradation of deltaA, leading to the activation of the canonical notch pathway (Diks et al., 2006, 2008). This recognition is specific to deltaA because d-Asb11 does not degrade deltaD (Diks et al., 2008). In zebrafish embryos, knockdown of d-Asb11 repressed specific delta–notch elements and their transcriptional targets, whereas these were induced when d-Asb11 was misexpressed (Diks et al., 2008). These data indicate that d-Asb11 regulates delta–notch signaling for the fine-tuning of lateral inhibition gradients between deltaA and notch (Diks et al., 2008).

CRL5Rab-40C complex and CRLMUF1 complex

The substrates of Rab-40C and MUF1 have not yet been identified. However, Rab-40C localizes in the perinuclear recycling compartment, suggesting its physiological role in receptor endocytosis (Rodriguez-Gabin et al., 2004). Given that the mRNA and protein level of Rab-40C increases as oligodendrocytes differentiate, it may be important in myelin formation (Rodriguez-Gabin et al., 2004).

Viral ECS-Type Ubiquitin Ligase

CRL2HPV16E7 complex

Human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 cause premalignant squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (Munger et al., 2004). Integration of viral DNA into the host genome leads to persistent and dysregulated expression of HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins, which is necessary for the induction and maintenance of the oncogenic transformation (Munger et al., 2004). HPV E7 contains incomplete Cul2 box and can bind to endogenous Cul2 (Huh et al., 2007). HPV E7 polyubiquitinates retinoblastoma tumor suppressor (pRB) and induces proteasomal degradation (Boyer et al., 1996; Berezutskaya et al., 1997; Jones and Munger, 1997; Huh et al., 2007).

CRL5Vif complex

The viral infectivity factor (Vif) protein of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) is also a Cul5-type ubiquitin ligase (Yu et al., 2003; Bergeron et al., 2010). Importantly, it has been suggested that the zinc-binding motif of Vif is important for its interaction with Cul5 (Yu et al., 2004; Mehle et al., 2006; Xiao et al., 2006). Vif polyubiquitinates and degrades the cellular intrinsic restriction factors APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G (Yu et al., 2003; Mehle et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005). Both APOBEC3F and G have cytidine deaminase activity and, when packaged into HIV-1 virions, cause uracil (U) to be substituted for cytosine (C) in newly synthesized minus-strand viral DNA (Sheehy et al., 2002; Harris et al., 2003; Lecossier et al., 2003; Mangeat et al., 2003; Mariani et al., 2003). The C-to-U mutation introduced into minus-strand viral DNA results in a guanine (G)-to-adenine (A) mutation in plus-strand viral DNA because U is read as T by DNA polymerases (Lecossier et al., 2003). These mutations cause amino acid substitutions, which affect the enzymatic activity of HIV-1 (Harris et al., 2003). Another possibility is that deoxyuridine in minus-strand viral DNA is targeted for excision by uracil-DNA glycosylase (Harris et al., 2003). These abasic sites are recognized and cleaved by endonucleases, inhibiting HIV-1 replication (Harris et al., 2003). Since the CRL5Vif complex targets APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G for proteasomal degradation, it is a potential target for the development of antiviral agents aimed at preventing the interaction between Vif and Cul5.

CRL5E4orf6 complex

The human adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) early region 4 34-kDa product from open reading frame 6 (E4orf6) contains three BC boxes (Blanchette et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2007, 2011). Although Ad5 E4orf6 forms complex containing Cul5, Elongin BC complex, and Rbx1, Cul5 box is not present in the Ad5 E4orf6 (Harada et al., 2002; Blanchette et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2011). Adenoviral protein E1B55K associates with the E4orf6 protein and recognizes substrate to be degraded by ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Blanchette et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2007). This complex is essential for efficient viral replication and some substrates have been identified, including p53 (Moore et al., 1996; Querido et al., 1997; Steegenga et al., 1998; Cathomen and Weitzman, 2000; Nevels et al., 2000; Shen et al., 2001), meiotic recombination 11 (Mre11; Stracker et al., 2002; Blanchette et al., 2004), DNA ligase IV (Baker et al., 2007), integrin α3 (Dallaire et al., 2009), and adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) Rep52 and capsid proteins (Nayak et al., 2008). The Mre11 complex consists of Mre11, RAD50, and Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 (NBS1, also known as nibrin) is a sensor of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and induces p53-dependent apoptosis (Stracker and Petrini, 2011). DNA ligase IV plays a pivotal role in repairing DSBs and the mutation of this gene results in ligase IV (LIG4) syndrome characterized by pronounced radiosensitivity, genome instability, malignancy, immunodeficiency, and bone marrow abnormalities (Chistiakov et al., 2009). Heterodimer of integrin α and β subunits functions as transmembrane receptor that links external ligands to intracellular signaling pathways. Integrin α3β1 heterodimer in which the α3 subunit is coupled to the β1 subunit binds a variety of extracellular matrix substrates, including fibronectin, collagen, vitronectin, and laminins (DiPersio et al., 1995). E4orf6/E1B55K ligase complex is involved in cell detachment from the extracellular matrix, which may contribute to virus spread (Dallaire et al., 2009). Although Cul5 is present in the E4orf6 complex of the human Ad5, Cul2 is primarily present in the E4orf6 complex of Ad12 and Ad40 (Cheng et al., 2011). Interestingly, E4orf6 complex of Ad16 binds Cul2 as well as Cul5 and is not able to degrade p53 and integrin α3 (Cheng et al., 2011). It remains unclear how E4orf6 complexes of each serotypes distinguish Cul2 from Cul5.

CRL5BZLF1 complex

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), a human γ-herpesvirus, is associated with several B cell and epithelial cell malignancies and there are two different infection states, latent, and lytic (Tsurumi, 2001). BZLF1 (known as Zta, EB1, or ZEBRA), is a transcriptional trans-activator that induces EBV early gene expression to activate an EBV lytic cycle cascade (Chevallier-Greco et al., 1986; Countryman et al., 1987; Hammerschmidt and Sugden, 1988; Sinclair et al., 1991). BZLF1 can bind to Cul2 and Cul5 because of presence of both Cul2 and Cul5 boxes (Sato et al., 2009a). BZLF1 polyubiquitinates and induces degradation of p53 (Sato et al., 2009a,b). The degradation of p53 prevents apoptosis and is required for the efficient viral propagation in the lytic replication.

Conclusion

The “classical” SOCS box proteins can be divided into two distinct families. Cul2 and Cul5 within the VHL box and SOCS box, respectively, determine the association with Rbx1 or Rbx2. Given that Rbx1 and Rbx2 specifically interact with Cul2 and Cul5, respectively, the functions of Rbx1 and Rbx2 are different from each other, at least in higher eukaryotes. Cul2- and Cul5-type ubiquitin ligases are structurally similar because they have the Elongin BC complex adaptor protein and Cullin scaffold protein in common. As with other ubiquitin ligases, these two have various substrates and physiological functions (Tables 1, 2, and 3) and may have arisen independently during evolution.

Table 1.

Cul2-type ubiquitin ligases and corresponding substrates.

| Ubiquitin ligase | Substrates | References |

|---|---|---|

| pVHL | HIFα | Ivan et al. (2001); Jaakkola et al. (2001); Masson et al. (2001); Hon et al. (2002) |

| Spry2 | Anderson et al. (2011) | |

| EGFR | Zhou and Yang (2011) | |

| Atypical PKC (PKCλ and ζII) | Okuda et al. (2001); Iturrioz and Parker (2007) | |

| RPB7 | Na et al. (2003) | |

| Rpb1 | Kuznetsova et al. (2003); Mikhaylova et al. (2008) | |

| LRR-1 | CKI-1 (in C. elegans) | Starostina et al. (2010) |

| p21Cip | Starostina et al. (2010) | |

| FEM1B | TRA-1 | Starostina et al. (2007) |

| Ankrd37 | Shi et al. (2011) |

Table 2.

Cul5-type ubiquitin ligases and corresponding substrates.

| Cul5-type ubiquitin ligases | Substrates | References |

|---|---|---|

| SOCS1 | JAK2 | Kamizono et al. (2001) |

| Vav | De Sepulveda et al. (2000) | |

| IRS1 and IRS2 | Rui et al. (2002) | |

| ElonginA | Rpb1 | Yasukawa et al. (2008) |

| SSB1, 2, and 4 | iNOS | Kuang et al. (2010); Nishiya et al. (2011) |

| WSB1 | HIPK2 | Choi et al. (2005, 2008) |

| D2 | Dentice et al. (2005) | |

| ASB2 | Filamin A and B | Heuze et al. (2008) |

| Jak3 | Nie et al. (2011); Wu and Sun (2011) | |

| ASB3 | TNF-R2 | Chung et al. (2005) |

| ASB4 | IRS4 | Li et al. (2011) |

| ASB6 | APS | Wilcox et al. (2004) |

| ASB9 | CKB | Debrincat et al. (2007) |

| ASB11 | DeltaA (in Danio rerio) | Diks et al. (2006, 2008) |

Table 3.

Viral ECS-type ubiquitin ligases and corresponding substrates.

| Viral ECS-type ubiquitin ligases | Substrates | References |

|---|---|---|

| HPV16E7 (Cul2-type) | pRB | Boyer et al. (1996); Berezutskaya et al. (1997); Jones and Munger (1997); Huh et al. (2007) |

| Vif (Cul5-type) | APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G | Yu et al. (2003); Mehle et al. (2004); Liu et al. (2005) |

| E4orf6 of Ad5 (Cul5-type) | p53 | Moore et al. (1996); Querido et al. (1997); Steegenga et al. (1998); Cathomen and Weitzman (2000); Nevels et al. (2000); Shen et al. (2001) |

| Mre11 | Stracker et al. (2002); Blanchette et al. (2004) | |

| DNA ligase IV | Baker et al. (2007) | |

| Integrin α3 | Dallaire et al. (2009) | |

| AAV5 Rep52 and capsid proteins | Nayak et al. (2008) | |

| E4orf6 of Ad16 (Cul2 and Cul5-type) | DNA ligase IV | Cheng et al. (2011) |

| BZLF1 (Cul2 and Cul5-type) | p53 | Sato et al. (2009a,b) |

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from Scientific Research on Innovative Areas and grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

References

- Aikawa Y., Nguyen L. A., Isono K., Takakura N., Tagata Y., Schmitz M. L., Koseki H., Kitabayashi I. (2006). Roles of HIPK1 and HIPK2 in AML1- and p300-dependent transcription, hematopoiesis and blood vessel formation. EMBO J. 25, 3955–3965 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K., Nordquist K. A., Gao X., Hicks K. C., Zhai B., Gygi S. P., Patel T. B. (2011). Regulation of cellular levels of Sprouty2 by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins and von-Hippel Lindau protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42027–42036 10.1074/jbc.M111.303222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravind L., Koonin E. V. (2000). The U box is a modified RING finger – a common domain in ubiquitination. Curr. Biol. 10, R132–R134 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00398-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso T., Lane W. S., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C. (1995). Elongin (SIII): a multisubunit regulator of elongation by RNA polymerase II. Science 269, 1439–1443 10.1126/science.7660129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babon J. J., Sabo J. K., Zhang J. G., Nicola N. A., Norton R. S. (2009). The SOCS box encodes a hierarchy of affinities for cullin5: implications for ubiquitin ligase formation and cytokine signalling suppression. J. Mol. Biol. 387, 162–174 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai C., Sen P., Hofmann K., Ma L., Goebl M., Harper J. W., Elledge S. J. (1996). SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 86, 263–274 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80098-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A., Rohleder K. J., Hanakahi L. A., Ketner G. (2007). Adenovirus E4 34k and E1b 55k oncoproteins target host DNA ligase IV for proteasomal degradation. J. Virol. 81, 7034–7040 10.1128/JVI.00029-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezutskaya E., Yu B., Morozov A., Raychaudhuri P., Bagchi S. (1997). Differential regulation of the pocket domains of the retinoblastoma family proteins by the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein. Cell Growth Differ. 8, 1277–1286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron J. R., Huthoff H., Veselkov D. A., Beavil R. L., Simpson P. J., Matthews S. J., Malim M. H., Sanderson M. R. (2010). The SOCS-box of HIV-1 Vif interacts with Elongin BC by induced-folding to recruit its Cul5-containing ubiquitin ligase complex. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000925. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berra E., Benizri E., Ginouves A., Volmat V., Roux D., Pouyssegur J. (2003). HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. EMBO J. 22, 4082–4090 10.1093/emboj/cdg392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A., Deng J. M., Zhang Z., Behringer R., de Crombrugghe B., Maity S. N. (2003). The B subunit of the CCAAT box binding transcription factor complex (CBF/NF-Y) is essential for early mouse development and cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 63, 8167–8172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette P., Cheng C. Y., Yan Q., Ketner G., Ornelles D. A., Dobner T., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Branton P. E. (2004). Both BC-box motifs of adenovirus protein E4orf6 are required to efficiently assemble an E3 ligase complex that degrades p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 9619–9629 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9619-9629.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer S. N., Wazer D. E., Band V. (1996). E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 56, 4620–4624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradsher J. N., Jackson K. W., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (1993a). RNA polymerase II transcription factor SIII. I. Identification, purification, and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 25587–25593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradsher J. N., Tan S., McLaury H. J., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C. (1993b). RNA polymerase II transcription factor SIII. II. Functional properties and role in RNA chain elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 25594–25603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathomen T., Weitzman M. D. (2000). A functional complex of adenovirus proteins E1B-55kDa and E4orf6 is necessary to modulate the expression level of p53 but not its transcriptional activity. J. Virol. 74, 11407–11412 10.1128/JVI.74.5.2372-2382.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. L., Yee K. S., Tan K. M., Yu V. C. (2000). The Caenorhabditis elegans sex determination protein FEM-1 is a CED-3 substrate that associates with CED-4 and mediates apoptosis in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17925–17928 10.1074/jbc.M004189200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. Y., Blanchette P., Branton P. E. (2007). The adenovirus E4orf6 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex assembles in a novel fashion. Virology 364, 36–44 10.1016/j.virol.2007.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. Y., Gilson T., Dallaire F., Ketner G., Branton P. E., Blanchette P. (2011). The E4orf6/E1B55K E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes of human adenoviruses exhibit heterogeneity in composition and substrate specificity. J. Virol. 85, 765–775 10.1128/JVI.01890-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier-Greco A., Manet E., Chavrier P., Mosnier C., Daillie J., Sergeant A. (1986). Both Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-encoded trans-acting factors, EB1 and EB2, are required to activate transcription from an EBV early promoter. EMBO J. 5, 3243–3249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chistiakov D. A., Voronova N. V., Chistiakov A. P. (2009). Ligase IV syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 52, 373–378 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. Y., Kim Y. H., Kim Y. O., Park S. J., Kim E. A., Riemenschneider W., Gajewski K., Schulz R. A., Kim Y. (2005). Phosphorylation by the DHIPK2 protein kinase modulates the corepressor activity of Groucho. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21427–21436 10.1074/jbc.M410521200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. W., Seo Y. M., Kim E. A., Sung K. S., Ahn J. W., Park S. J., Lee S. R., Choi C. Y. (2008). Ubiquitination and degradation of homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 by WD40 repeat/SOCS box protein WSB-1. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4682–4689 10.1074/jbc.M803695200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung A. S., Guan Y. J., Yuan Z. L., Albina J. E., Chin Y. E. (2005). Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box 3 (ASB3) mediates ubiquitination and degradation of tumor necrosis factor receptor II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4716–4726 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4716-4726.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway J. W., Kamura T., Conaway R. C. (1998). The Elongin BC complex and the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1377, M49–M54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costessi A., Mahrour N., Tijchon E., Stunnenberg R., Stoel M. A., Jansen P. W., Sela D., Martin-Brown S., Washburn M. P., Florens L., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C., Stunnenberg H. G. (2011). The tumour antigen PRAME is a subunit of a Cul2 ubiquitin ligase and associates with active NFY promoters. EMBO J. 30, 3786–3798 10.1038/emboj.2011.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Countryman J., Jenson H., Seibl R., Wolf H., Miller G. (1987). Polymorphic proteins encoded within BZLF1 of defective and standard Epstein-Barr viruses disrupt latency. J. Virol. 61, 3672–3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr D. M., Hohfeld J., Patterson C. (2002). Protein quality control: U-box-containing E3 ubiquitin ligases join the fold. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 368–375 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02125-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire F., Blanchette P., Groitl P., Dobner T., Branton P. E. (2009). Identification of integrin alpha3 as a new substrate of the adenovirus E4orf6/E1B 55-kilodalton E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. J. Virol. 83, 5329–5338 10.1128/JVI.00089-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sepulveda P., Ilangumaran S., Rottapel R. (2000). Suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 inhibits VAV function through protein degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14005–14008 10.1074/jbc.C000106200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrincat M. A., Zhang J. G., Willson T. A., Silke J., Connolly L. M., Simpson R. J., Alexander W. S., Nicola N. A., Kile B. T., Hilton D. J. (2007). Ankyrin repeat and suppressors of cytokine signaling box protein Asb-9 targets creatine kinase B for degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 4728–4737 10.1074/jbc.M609164200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentice M., Bandyopadhyay A., Gereben B., Callebaut I., Christoffolete M. A., Kim B. W., Nissim S., Mornon J. P., Zavacki A. M., Zeold A., Capelo L. P., Curcio-Morelli C., Ribeiro R., Harney J. W., Tabin C. J., Bianco A. C. (2005). The hedgehog-inducible ubiquitin ligase subunit WSB-1 modulates thyroid hormone activation and PTHrP secretion in the developing growth plate. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 698–705 10.1038/ncb1272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diks S. H., Bink R. J., van de Water S., Joore J., van Rooijen C., Verbeek F. J., den Hertog J., Peppelenbosch M. P., Zivkovic D. (2006). The novel gene asb11: a regulator of the size of the neural progenitor compartment. J. Cell Biol. 174, 581–592 10.1083/jcb.200601081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diks S. H., Sartori da Silva M. A., Hillebrands J. L., Bink R. J., Versteeg H. H., van Rooijen C., Brouwers A., Chitnis A. B., Peppelenbosch M. P., Zivkovic D. (2008). d-Asb11 is an essential mediator of canonical delta-notch signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1190–1198 10.1038/ncb1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio C. M., Shah S., Hynes R. O. (1995). Alpha 3A beta 1 integrin localizes to focal contacts in response to diverse extracellular matrix proteins. J. Cell Sci. 108(Pt 6), 2321–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Orazi G., Cecchinelli B., Bruno T., Manni I., Higashimoto Y., Saito S., Gostissa M., Coen S., Marchetti A., Del Sal G., Piaggio G., Fanciulli M., Appella E., Soddu S. (2002). Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 phosphorylates p53 at Ser 46 and mediates apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 11–19 10.1038/ncb714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxakis E., Huang E. J., Davies A. M. (2004). Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 regulates apoptosis in developing sensory and sympathetic neurons. Curr. Biol. 14, 1761–1765 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D. R., Pause A., Burgess W. H., Aso T., Chen D. Y., Garrett K. P., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Linehan W. M., Klausner R. D. (1995). Inhibition of transcription elongation by the VHL tumor suppressor protein. Science 269, 1402–1406 10.1126/science.7660122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T. A., Masuhara M., Yokouchi M., Suzuki R., Sakamoto H., Mitsui K., Matsumoto A., Tanimura S., Ohtsubo M., Misawa H., Miyazaki T., Leonor N., Taniguchi T., Fujita T., Kanakura Y., Komiya S., Yoshimura A. (1997). A new protein containing an SH2 domain that inhibits JAK kinases. Nature 387, 921–924 10.1038/43213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A. C., Gleadle J. M., McNeill L. A., Hewitson K. S., O’Rourke J., Mole D. R., Mukherji M., Metzen E., Wilson M. I., Dhanda A., Tian Y. M., Masson N., Hamilton D. L., Jaakkola P., Barstead R., Hodgkin J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Schofield C. J., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001). C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107, 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F. C. (1997). Perspectives series: host/pathogen interactions. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-related antimicrobial activity. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 2818–2825 10.1172/JCI119473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freemont P. S. (2000). RING for destruction? Curr. Biol. 10, R84–R87 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00287-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett K. P., Aso T., Bradsher J. N., Foundling S. I., Lane W. S., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (1995). Positive regulation of general transcription factor SIII by a tailed ubiquitin homolog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7172–7176 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett K. P., Tan S., Bradsher J. N., Lane W. S., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C. (1994). Molecular cloning of an essential subunit of RNA polymerase II elongation factor SIII. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5237–5241 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnarra J. R., Tory K., Weng Y., Schmidt L., Wei M. H., Li H., Latif F., Liu S., Chen F., Duh F.-M., Lubensky I., Duan D. R., Florence C., Pozzatti R., Walther M. M., Bander N. H., Grossman H. B., Brauch H., Pomer S., Brooks J. D., Isaacs W. B., Lerman M. I., Zbar B., Linehan W. M. (1994). Mutations of the VHL tumour suppressor gene in renal carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 7, 85–90 10.1038/ng0594-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnarra J. R., Zhou S., Merrill M. J., Wagner J. R., Krumm A., Papavassiliou E., Oldfield E. H., Klausner R. D., Linehan W. M. (1996). Post-transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by the product of the VHL tumor suppressor gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 10589–10594 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guibal F. C., Moog-Lutz C., Smolewski P., Di Gioia Y., Darzynkiewicz Z., Lutz P. G., Cayre Y. E. (2002). ASB-2 inhibits growth and promotes commitment in myeloid leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 218–224 10.1074/jbc.M108476200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt W., Sugden B. (1988). Identification and characterization of oriLyt, a lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus. Cell 55, 427–433 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90028-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada J. N., Shevchenko A., Pallas D. C., Berk A. J. (2002). Analysis of the adenovirus E1B-55K-anchored proteome reveals its link to ubiquitination machinery. J. Virol. 76, 9194–9206 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9194-9206.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. S., Bishop K. N., Sheehy A. M., Craig H. M., Petersen-Mahrt S. K., Watt I. N., Neuberger M. S., Malim M. H. (2003). DNA deamination mediates innate immunity to retroviral infection. Cell 113, 803–809 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00423-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama S., Yada M., Matsumoto M., Ishida N., Nakayama K. I. (2001). U box proteins as a new family of ubiquitin-protein ligases. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33111–33120 10.1074/jbc.M102755200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J. G., Graff J. R., Myohanen S., Nelkin B. D., Baylin S. B. (1996). Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9821–9826 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. (1992). The ubiquitin system for protein degradation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61, 761–807 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. (1998). The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuze M. L., Lamsoul I., Baldassarre M., Lad Y., Leveque S., Razinia Z., Moog-Lutz C., Calderwood D. A., Lutz P. G. (2008). ASB2 targets filamins A and B to proteasomal degradation. Blood 112, 5130–5140 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton D. J., Richardson R. T., Alexander W. S., Viney E. M., Willson T. A., Sprigg N. S., Starr R., Nicholson S. E., Metcalf D., Nicola N. A. (1998). Twenty proteins containing a C-terminal SOCS box form five structural classes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 114–119 10.1073/pnas.95.1.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J., Doniach T., Shen M. (1985). The sex determination pathway in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: variations on a theme. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 50, 585–593 10.1101/SQB.1985.050.01.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T. G., Moller A., Sirma H., Zentgraf H., Taya Y., Droge W., Will H., Schmitz M. L. (2002). Regulation of p53 activity by its interaction with homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 1–10 10.1038/ncb715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon W. C., Wilson M. I., Harlos K., Claridge T. D., Schofield C. J., Pugh C. W., Maxwell P. H., Ratcliffe P. J., Stuart D. I., Jones E. Y. (2002). Structural basis for the recognition of hydroxyproline in HIF-1 alpha by pVHL. Nature 417, 975–978 10.1038/nature00767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh K., Zhou X., Hayakawa H., Cho J. Y., Libermann T. A., Jin J., Harper J. W., Munger K. (2007). Human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein associates with the cullin 2 ubiquitin ligase complex, which contributes to degradation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor. J. Virol. 81, 9737–9747 10.1128/JVI.00881-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse J. M., Scheffner M., Beaudenon S., Howley P. M. (1995). A family of proteins structurally and functionally related to the E6-AP ubiquitin-protein ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 2563–2567 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5249a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulos O., Levy A. P., Jiang C., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Goldberg M. A. (1996). Negative regulation of hypoxia-inducible genes by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 10595–10599 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturrioz X., Parker P. J. (2007). PKCzetaII is a target for degradation through the tumour suppressor protein pVHL. FEBS Lett. 581, 1397–1402 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan M., Kondo K., Yang H., Kim W., Valiando J., Ohh M., Salic A., Asara J. M., Lane W. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2001). HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 292, 464–468 10.1126/science.1059817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P., Mole D. R., Tian Y. M., Wilson M. I., Gielbert J., Gaskell S. J., Kriegsheim A., Hebestreit H. F., Mukherji M., Schofield C. J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001). Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292, 468–472 10.1126/science.1059796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager S., Schwartz H. T., Horvitz H. R., Conradt B. (2004). The Caenorhabditis elegans F-box protein SEL-10 promotes female development and may target FEM-1 and FEM-3 for degradation by the proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12549–12554 10.1073/pnas.0405087101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joazeiro C. A., Weissman A. M. (2000). RING finger proteins: mediators of ubiquitin ligase activity. Cell 102, 549–552 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00077-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. L., Munger K. (1997). Analysis of the p53-mediated G1 growth arrest pathway in cells expressing the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. J. Virol. 71, 2905–2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamizono S., Hanada T., Yasukawa H., Minoguchi S., Kato R., Minoguchi M., Hattori K., Hatakeyama S., Yada M., Morita S., Kitamura T., Kato H., Nakayama K. I., Yoshimura A. (2001). The SOCS box of SOCS-1 accelerates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of TEL-JAK2. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12530–12538 10.1074/jbc.M010074200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T., Burian D., Yan Q., Schmidt S. L., Lane W. S., Querido E., Branton P. E., Shilatifard A., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2001). Muf1, a novel Elongin BC-interacting leucine-rich repeat protein that can assemble with Cul5 and Rbx1 to reconstitute a ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29748–29753 10.1074/jbc.M103093200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T., Koepp D. M., Conrad M. N., Skowyra D., Moreland R. J., Iliopoulos O., Lane W. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Elledge S. J., Conaway R. C., Harper J. W., Conaway J. W. (1999). Rbx1, a component of the VHL tumor suppressor complex and SCF ubiquitin ligase. Science 284, 657–661 10.1126/science.284.5414.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T., Maenaka K., Kotoshiba S., Matsumoto M., Kohda D., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Nakayama K. I. (2004). VHL-box and SOCS-box domains determine binding specificity for Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules of ubiquitin ligases. Genes Dev. 18, 3055–3065 10.1101/gad.1252404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanei-Ishii C., Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Tanikawa J., Nomura T., Ishitani T., Kishida S., Kokura K., Kurahashi T., Ichikawa-Iwata E., Kim Y., Matsumoto K., Ishii S. (2004). Wnt-1 signal induces phosphorylation and degradation of c-Myb protein via TAK1, HIPK2, and NLK. Genes Dev. 18, 816–829 10.1101/gad.1170604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibel A., Iliopoulos O., DeCaprio J. A., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (1995). Binding of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein to Elongin B and C. Science 269, 1444–1446 10.1126/science.7660130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kile B. T., Schulman B. A., Alexander W. S., Nicola N. A., Martin H. M., Hilton D. J. (2002). The SOCS box: a tale of destruction and degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 235–241 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. A., Noh Y. T., Ryu M. J., Kim H. T., Lee S. E., Kim C. H., Lee C., Kim Y. H., Choi C. Y. (2006). Phosphorylation and transactivation of Pax6 by homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 7489–7497 10.1074/jbc.M507227200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. J., Park J. S., Um S. J. (2002). Identification and characterization of HIPK2 interacting with p73 and modulating functions of the p53 family in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32020–32028 10.1074/jbc.M204710200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida T., Stackhouse T. M., Chen F., Lerman M. I., Zbar B. (1995). Cellular proteins that bind the von Hippel-Lindau disease gene product: mapping of binding domains and the effect of missense mutations. Cancer Res. 55, 4544–4548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourembanas S., Hannan R. L., Faller D. V. (1990). Oxygen tension regulates the expression of the platelet-derived growth factor-B chain gene in human endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 86, 670–674 10.1172/JCI114759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang Z., Lewis R. S., Curtis J. M., Zhan Y., Saunders B. M., Babon J. J., Kolesnik T. B., Low A., Masters S. L., Willson T. A., Kedzierski L., Yao S., Handman E., Norton R. S., Nicholson S. E. (2010). The SPRY domain-containing SOCS box protein SPSB2 targets iNOS for proteasomal degradation. J. Cell Biol. 190, 129–141 10.1083/jcb.200912087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A. V., Meller J., Schnell P. O., Nash J. A., Ignacak M. L., Sanchez Y., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C., Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F. (2003). von Hippel-Lindau protein binds hyperphosphorylated large subunit of RNA polymerase II through a proline hydroxylation motif and targets it for ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2706–2711 10.1073/pnas.0436037100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai E. C. (2004). Notch signaling: control of cell communication and cell fate. Development 131, 965–973 10.1242/dev.01074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif F., Tory K., Gnarra J., Yao M., Duh F.-M., Orcutt M. L., Stackhouse T., Kuzmin I., Modi W., Geil L., Schmidt L., Zhou F., Li H., Wei M. H., Chen F., Glenn G., Choyke P., Walther M. W., Weng Y., Duan D.-S. R., Dean M., Glavač D., Richards F. M., Crossey P. A., Ferguson-Smith M. A., Paslier D. L., Chumakov I., Cohen D., Chinault A. C., Maher E. R., Linehan W. M., Zbar B., Lerman M. I. (1993). Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science 260, 1317–1320 10.1126/science.8493574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecossier D., Bouchonnet F., Clavel F., Hance A. J. (2003). Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein. Science 300, 1112. 10.1126/science.1083338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Y., Chai B., Zhang W., Wu X., Zhang C., Fritze D., Xia Z., Patterson C., Mulholland M. W. (2011). Ankyrin repeat and SOCS box containing protein 4 (Asb-4) colocalizes with insulin receptor substrate 4 (IRS4) in the hypothalamic neurons and mediates IRS4 degradation. BMC Neurosci. 12, 95. 10.1186/1471-2202-12-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkowitz S., Weissman A. M. (2011). RINGs of good and evil: RING finger ubiquitin ligases at the crossroads of tumour suppression and oncogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 629–643 10.1038/nrc3120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Sarkis P. T., Luo K., Yu Y., Yu X. F. (2005). Regulation of Apobec3F and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vif by Vif-Cul5-ElonB/C E3 ubiquitin ligase. J. Virol. 79, 9579–9587 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14507-14515.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. V., Baek J. H., Zhang H., Diez R., Cole R. N., Semenza G. L. (2007). RACK1 competes with HSP90 for binding to HIF-1alpha and is required for O(2)-independent and HSP90 inhibitor-induced degradation of HIF-1alpha. Mol. Cell 25, 207–217 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorick K. L., Jensen J. P., Fang S., Ong A. M., Hatakeyama S., Weissman A. M. (1999). RING fingers mediate ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2)-dependent ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11364–11369 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A., Artavanis-Tsakonas S. (2006). Notch signalling in vertebrate neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 93–102 10.1038/nrn1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein C. J., Padalko E. (2004). iNOS (NOS2) at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 117, 2865–2867 10.1242/jcs.01166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K., Ehrlich E., Xiao Z., Zhang W., Ketner G., Yu X. F. (2007). Adenovirus E4orf6 assembles with Cullin5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase through an HIV/SIV Vif-like BC-box to regulate p53. FASEB J. 21, 1742–1750 10.1096/fj.06-7241com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahrour N., Redwine W. B., Florens L., Swanson S. K., Martin-Brown S., Bradford W. D., Staehling-Hampton K., Washburn M. P., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2008). Characterization of cullin-box sequences that direct recruitment of Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules to Elongin BC-based ubiquitin ligases. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8005–8013 10.1074/jbc.M706987200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeat B., Turelli P., Caron G., Friedli M., Perrin L., Trono D. (2003). Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts. Nature 424, 99–103 10.1038/nature01709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani R., Chen D., Schrofelbauer B., Navarro F., Konig R., Bollman B., Munk C., Nymark-McMahon H., Landau N. R. (2003). Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell 114, 21–31 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00515-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson N., Willam C., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001). Independent function of two destruction domains in hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha chains activated by prolyl hydroxylation. EMBO J. 20, 5197–5206 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell P. H., Wiesener M. S., Chang G. W., Clifford S. C., Vaux E. C., Cockman M. E., Wykoff C. C., Pugh C. W., Maher E. R., Ratcliffe P. J. (1999). The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399, 271–275 10.1038/20459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehle A., Goncalves J., Santa-Marta M., McPike M., Gabuzda D. (2004). Phosphorylation of a novel SOCS-box regulates assembly of the HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 complex that promotes APOBEC3G degradation. Genes Dev. 18, 2861–2866 10.1101/gad.1249904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehle A., Thomas E. R., Rajendran K. S., Gabuzda D. (2006). A zinc-binding region in Vif binds Cul5 and determines cullin selection. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17259–17265 10.1074/jbc.M602413200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaylova O., Ignacak M. L., Barankiewicz T. J., Harbaugh S. V., Yi Y., Maxwell P. H., Schneider M., Van Geyte K., Carmeliet P., Revelo M. P., Wyder M., Greis K. D., Meller J., Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F. (2008). The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and Egl-9-Type proline hydroxylases regulate the large subunit of RNA polymerase II in response to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 2701–2717 10.1128/MCB.01231-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller A., Sirma H., Hofmann T. G., Rueffer S., Klimczak E., Droge W., Will H., Schmitz M. L. (2003a). PML is required for homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2)-mediated p53 phosphorylation and cell cycle arrest but is dispensable for the formation of HIPK domains. Cancer Res. 63, 4310–4314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller A., Sirma H., Hofmann T. G., Staege H., Gresko E., Ludi K. S., Klimczak E., Droge W., Will H., Schmitz M. L. (2003b). Sp100 is important for the stimulatory effect of homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 on p53-dependent gene expression. Oncogene 22, 8731–8737 10.1038/sj.onc.1207079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M., Horikoshi N., Shenk T. (1996). Oncogenic potential of the adenovirus E4orf6 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 11295–11301 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumm J. S., Kopan R. (2000). Notch signaling: from the outside in. Dev. Biol. 228, 151–165 10.1006/dbio.2000.9960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger K., Baldwin A., Edwards K. M., Hayakawa H., Nguyen C. L., Owens M., Grace M., Huh K. (2004). Mechanisms of human papillomavirus-induced oncogenesis. J. Virol. 78, 11451–11460 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11451-11460.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na X., Duan H. O., Messing E. M., Schoen S. R., Ryan C. K., di Sant’Agnese P. A., Golemis E. A., Wu G. (2003). Identification of the RNA polymerase II subunit hsRPB7 as a novel target of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. EMBO J. 22, 4249–4259 10.1093/emboj/cdg410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka T., Narazaki M., Hirata M., Matsumoto T., Minamoto S., Aono A., Nishimoto N., Kajita T., Taga T., Yoshizaki K., Akira S., Kishimoto T. (1997). Structure and function of a new STAT-induced STAT inhibitor. Nature 387, 924–929 10.1038/43219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nara H., Onoda T., Rahman M., Araki A., Juliana F. M., Tanaka N., Asao H. (2011). WSB-1, a novel IL-21 receptor binding molecule, enhances the maturation of IL-21 receptor. Cell. Immunol. 269, 54–59 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C., Shiloh M. U. (2000). Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8841–8848 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak R., Farris K. D., Pintel D. J. (2008). E4Orf6-E1B-55k-dependent degradation of de novo-generated adeno-associated virus type 5 Rep52 and capsid proteins employs a cullin 5-containing E3 ligase complex. J. Virol. 82, 3803–3808 10.1128/JVI.02532-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevels M., Rubenwolf S., Spruss T., Wolf H., Dobner T. (2000). Two distinct activities contribute to the oncogenic potential of the adenovirus type 5 E4orf6 protein. J. Virol. 74, 5168–5181 10.1128/JVI.74.11.5168-5181.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie L., Zhao Y., Wu W., Yang Y. Z., Wang H. C., Sun X. H. (2011). Notch-induced Asb2 expression promotes protein ubiquitination by forming non-canonical E3 ligase complexes. Cell Res. 21, 754–769 10.1038/cr.2010.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiya T., Matsumoto K., Maekawa S., Kajita E., Horinouchi T., Fujimuro M., Ogasawara K., Uehara T., Miwa S. (2011). Regulation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase by the SPRY domain- and SOCS box-containing proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9009–9019 10.1074/jbc.M110.190678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan S., Russell D. S. (1999). Discrete expression of insulin receptor substrate-4 mRNA in adult rat brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 72, 97–102 10.1016/S0169-328X(99)00160-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T., Michel J. J., Schottelius A. J., Xiong Y. (1999). ROC1, a homolog of APC11, represents a family of cullin partners with an associated ubiquitin ligase activity. Mol. Cell 3, 535–541 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80482-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda H., Saitoh K., Hirai S., Iwai K., Takaki Y., Baba M., Minato N., Ohno S., Shuin T. (2001). The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein mediates ubiquitination of activated atypical protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43611–43617 10.1074/jbc.M107880200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson S. J., Le Good J. A., Whelan R. D., Whitehead P., Parker P. J. (2004). Identification of PKCzetaII: an endogenous inhibitor of cell polarity. EMBO J. 23, 77–88 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause A., Lee S., Worrell R. A., Chen D. Y., Burgess W. H., Linehan W. M., Klausner R. D. (1997). The von Hippel-Lindau tumor-suppressor gene product forms a stable complex with human CUL-2, a member of the Cdc53 family of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2156–2161 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. M. (1998). SCF and APC: the Yin and Yang of cell cycle regulated proteolysis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10, 759–768 10.1016/S0955-0674(98)80119-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piessevaux J., Lavens D., Peelman F., Tavernier J. (2008). The many faces of the SOCS box. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 19, 371–381 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querido E., Marcellus R. C., Lai A., Charbonneau R., Teodoro J. G., Ketner G., Branton P. E. (1997). Regulation of p53 levels by the E1B 55-kilodalton protein and E4orf6 in adenovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 71, 3788–3798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram P. A., Waxman D. J. (1999). SOCS/CIS protein inhibition of growth hormone-stimulated STAT5 signaling by multiple mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35553–35561 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Gabin A. G., Almazan G., Larocca J. N. (2004). Vesicle transport in oligodendrocytes: probable role of Rab40c protein. J. Neurosci. Res. 76, 758–770 10.1002/jnr.20121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L., Yuan M., Frantz D., Shoelson S., White M. F. (2002). SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 block insulin signaling by ubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRS1 and IRS2. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42394–42398 10.1074/jbc.M208099200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori da Silva M. A., Tee J. M., Paridaen J., Brouwers A., Runtuwene V., Zivkovic D., Diks S. H., Guardavaccaro D., Peppelenbosch M. P. (2010). Essential role for the d-Asb11 cul5 Box domain for proper notch signaling and neural cell fate decisions in vivo. PLoS ONE 5, e14023. 10.1371/journal.pone.0014023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Kamura T., Shirata N., Murata T., Kudoh A., Iwahori S., Nakayama S., Isomura H., Nishiyama Y., Tsurumi T. (2009a). Degradation of phosphorylated p53 by viral protein-ECS E3 ligase complex. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000530. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Shirata N., Kudoh A., Iwahori S., Nakayama S., Murata T., Isomura H., Nishiyama Y., Tsurumi T. (2009b). Expression of Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 immediate-early protein induces p53 degradation independent of MDM2, leading to repression of p53-mediated transcription. Virology 388, 204–211 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner M., Nuber U., Huibregtse J. M. (1995). Protein ubiquitination involving an E1-E2-E3 enzyme ubiquitin thioester cascade. Nature 373, 81–83 10.1038/373081a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol J. H., Feldman R. M., Zachariae W., Shevchenko A., Correll C. C., Lyapina S., Chi Y., Galova M., Claypool J., Sandmeyer S., Nasmyth K., Deshaies R. J., Shevchenko A., Deshaies R. J. (1999). Cdc53/cullin and the essential Hrt1 RING-H2 subunit of SCF define a ubiquitin ligase module that activates the E2 enzyme Cdc34. Genes Dev. 13, 1614–1626 10.1101/gad.13.12.1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy A. M., Gaddis N. C., Choi J. D., Malim M. H. (2002). Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418, 646–650 10.1038/nature00939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Kitzes G., Nye J. A., Fattaey A., Hermiston T. (2001). Analyses of single-amino-acid substitution mutants of adenovirus type 5 E1B-55K protein. J. Virol. 75, 4297–4307 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10543-10549.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. Q., Liao S. Y., Zhuang X. J., Han C. S. (2011). Mouse Fem1b interacts with and induces ubiquitin-mediated degradation of Ankrd37. Gene 485, 153–159 10.1016/j.gene.2011.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair A. J., Brimmell M., Shanahan F., Farrell P. J. (1991). Pathways of activation of the Epstein-Barr virus productive cycle. J. Virol. 65, 2237–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D., Koepp D. M., Kamura T., Conrad M. N., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Elledge S. J., Harper J. W. (1999). Reconstitution of G1 cyclin ubiquitination with complexes containing SCFGrr1 and Rbx1. Science 284, 662–665 10.1126/science.284.5414.662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starostina N. G., Lim J. M., Schvarzstein M., Wells L., Spence A. M., Kipreos E. T. (2007). A CUL-2 ubiquitin ligase containing three FEM proteins degrades TRA-1 to regulate C. elegans sex determination. Dev. Cell 13, 127–139 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starostina N. G., Simpliciano J. M., McGuirk M. A., Kipreos E. T. (2010). CRL2(LRR-1) targets a CDK inhibitor for cell cycle control in C. elegans and actin-based motility regulation in human cells. Dev. Cell 19, 753–764 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr R., Willson T. A., Viney E. M., Murray L. J., Rayner J. R., Jenkins B. J., Gonda T. J., Alexander W. S., Metcalf D., Nicola N. A., Hilton D. J. (1997). A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signalling. Nature 387, 917–921 10.1038/43206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegenga W. T., Riteco N., Jochemsen A. G., Fallaux F. J., Bos J. L. (1998). The large E1B protein together with the E4orf6 protein target p53 for active degradation in adenovirus infected cells. Oncogene 16, 349–357 10.1038/sj.onc.1201540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker T. H., Carson C. T., Weitzman M. D. (2002). Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature 418, 348–352 10.1038/nature00863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracker T. H., Petrini J. H. (2011). The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 90–103 10.1038/nrm3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subauste M. C., Ventura-Holman T., Du L., Subauste J. S., Chan S. L., Yu V. C., Maher J. F. (2009). RACK1 downregulates levels of the pro-apoptotic protein Fem1b in apoptosis-resistant colon cancer cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 8, 2297–2305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Yamanaka T., Hirose T., Manabe N., Mizuno K., Shimizu M., Akimoto K., Izumi Y., Ohnishi T., Ohno S. (2001). Atypical protein kinase C is involved in the evolutionarily conserved par protein complex and plays a critical role in establishing epithelia-specific junctional structures. J. Cell Biol. 152, 1183–1196 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svejstrup J. Q. (2002). Mechanisms of transcription-coupled DNA repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 21–29 10.1038/nrm703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamiya T., Kashiwagi I., Takahashi R., Yasukawa H., Yoshimura A. (2011). Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins and JAK/STAT pathways: regulation of T-cell inflammation by SOCS1 and SOCS3. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31, 980–985 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P., Fuchs S. Y., Chen A., Wu K., Gomez C., Ronai Z., Pan Z. Q. (1999). Recruitment of a ROC1-CUL1 ubiquitin ligase by Skp1 and HOS to catalyze the ubiquitination of I kappa B alpha. Mol. Cell 3, 527–533 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80481-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]