Abstract

Bone is a fundamental component of the disordered joint homeostasis seen in osteoarthritis, a disease that has been primarily characterized by the breakdown of articular cartilage accompanied by local bone changes and a limited degree of joint inflammation. In this review we consider the role of computed tomography imaging and computational analysis in osteoarthritis research, focusing on subchondral bone and osteophytes in the hip. We relate what is already known in this area to what could be explored through this approach in the future in relation to both clinical research trials and the underlying cellular and molecular science of osteoarthritis. We also consider how this area of research could impact on our understanding of the genetics of osteoarthritis.

Keywords: bone, hip, osteoarthritis, subchondral, osteophyte, morphology, histology, genetics

Background

Osteoarthritis is a disease that has been primarily characterized by the breakdown of articular cartilage accompanied by local bone changes and a limited degree of joint inflammation. It is a leading cause of morbidity causing pain, disability, and loss of function through chronic, progressive joint degeneration. Hip joint osteoarthritis causes an enormous health burden, with an estimated radiographic prevalence of 5% in the population over 65 years of age (Lane, 2007), with actual radiographic and clinical disease prevalence likely to be much higher (Mannoni et al., 2003; Dagenais et al., 2009). It has also been identified as a leading cause of debilitating pain in the general population (Ingvarsson, 2000).

Previously considered a primary disorder of articular cartilage, it is now recognized that cartilage, synovium, and bone respond in concert to mechanical stresses (Samuels et al., 2008), derangement of which can alter joint homeostasis and lead to the pathological processes of cartilage destruction, synovitis, and subchondral bone alteration (Goldring and Goldring, 2007).

Imaging remains an integral part of clinical and research investigation into osteoarthritis. Each imaging modality has its own recognized strengths and limitations, but all techniques ultimately have some contributory value toward advancing our understanding of the disease. In this review we consider the developing role for computed tomography (CT) imaging and computational analysis in osteoarthritis research, focusing on subchondral bone and osteophytes in the hip. We relate what is already known in this field to what could be explored through this approach in the future in relation to both clinical research trials and the underlying cellular and molecular science of osteoarthritis. We also consider how this area of research could impact on the genetics of this disease.

Defining Hip Osteoarthritis and Its Risk Factors

A number of risk factors that predispose to hip osteoarthritis have been identified, which have included demographic measures such as age and sex and more complex interactions between genetics, lifestyle, and joint morphology (Figure 1). Hip degeneration secondary to systemic disorders (e.g., hyperparathyroidism, acromegaly, and hemochromatosis) and local disorders (e.g., Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease, inflammatory arthritis, and traumatic injury) are also well documented (Lane, 2007). However, these factors only account for a small fraction of what has been termed “primary” osteoarthritis, an umbrella term for a variably painful disease that is poorly defined and whose pathophysiology is only patchily understood.

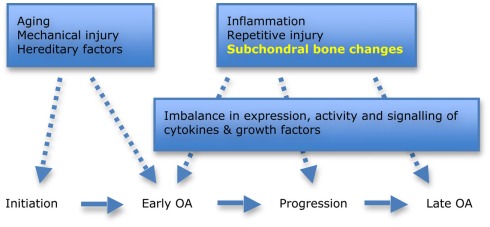

Figure 1.

Factors involved in the initiation and progression of hip osteoarthritis (OA). Aging, mechanical injury, and hereditary factors are all important when considering the role of morphology in disease initiation. Subchondral bone changes are now recognized as playing an important role in early disease and progression. Adapted from Goldring and Goldring (2007).

Although biochemical biomarkers such as urinary CTX-II (C-terminal crosslinked telopeptide of type II collagen) and markers linked to matrix metalloproteinase activity have been able to help define subgroups in the heterogeneous population of osteoarthritis sufferers, they have still fallen short of being able to provide reliably predictive information at the pre-radiographic stage of the disease, particularly with regard to making a diagnosis in disease-naïve individuals (Patra and Sandell, 2011). The approach through genetics and the application of genome-wide association studies may yet provide insight into new susceptibility loci, but significant and clinically relevant results are still awaited – see below (Loughlin, 2011).

If we consider a morphological perspective, it is worth noting that some structural features of hip osteoarthritis have been recognized since prehistory (Dequeker and Luyten, 2008). While we are interested in refining a number of the characteristic anatomical and morphological features of hip osteoarthritis using current CT imaging technology, one key problem is that morphological osteoarthritis does not always produce significant symptoms or lead to relevant clinical outcomes such as joint replacement. Much work has to be done to identify precisely which morphological and structural risk factors lead to clinically important outcomes in hip osteoarthritis. Mechanics and morphology research, having finally translated into the clinic through multi-detector CT (MDCT) imaging, is ideally suited to addressing this question, the answers to which are badly needed by the large genetic studies of osteoarthritis.

Subchondral Bone

While cartilage has historically been the principal target tissue in osteoarthritis research, bone has become increasingly appreciated as integral to pathogenesis (Samuels et al., 2008). Its structural, cellular, and biochemical properties are becoming key areas of research, for example with biomarker analyses demonstrating that decreased bone synthesis is linked to increased cartilage failure and that higher bone remodeling activity may be protective against cartilage loss (Patra and Sandell, 2011). Subchondral bone has also been considered a potential source for the nociceptive signals that cause disabling pain (Dieppe and Lohmander, 2005). As a result of this central role in the disease process, bone has also become a potential target for therapies (Kwan Tat et al., 2010).

Alterations in subchondral bone – seen radiographically as sclerosis and cyst formation – were previously thought to be a late manifestation. However, changes have been detected in this tissue much earlier in the disease process. Subchondral trabecular bone thickening has been observed in individuals with osteoarthritis compared to controls (Chiba et al., 2011). Subchondral bone remodeling has also been detected prior to cartilage degeneration in an animal model of osteoarthritis (Hayami et al., 2004). Lack of thickening of the subchondral bone plate has been shown to be protective against cartilage degeneration in knock-out animals versus wild type controls in a surgically induced model (Botter et al., 2009), while Neogi et al. (2009) have demonstrated that loss of bone resulting in a change of the articular bone shape had a strong association with future cartilage loss in the same sub-region of the knee over 30 months, introducing a potentially predictive element from determining bone changes. From a biomechanical perspective, the elastic modulus of subchondral bone in the medial tibial condyle has been demonstrated to be reduced by 60% (hence reduced stiffness) in subjects with overlying cartilage damage compared to normal controls (Day et al., 2001).

While these studies suggest that changing subchondral bone characteristics are central to the development and early progression of osteoarthritis and could be implicated as biomarkers for future disease, their precise behavior in human osteoarthritis is yet to be established. This lack of understanding is exemplified by our knowledge of the relationship between osteoarthritis and bone mineral density. While the long-standing view has been that osteoarthritis and osteoporosis have an inverse relationship, with increased bone density being implicated in cartilage defect development (Dore et al., 2009), one recently published opinion is that both abnormally low and high local bone densities predispose to osteoarthritis (Herrero-Beaumont et al., 2009). It seems likely that such contradictions have arisen because of a limited understanding of the true geographical variations in bone mineral density and variability in applied measurement, for example with increased bone mineral density in the subchondral bone plate (from reactive sclerosis) being combined with reduced underlying trabecular bone density (from increased bone turnover) in osteoarthritis. The relationship of bone stiffness with overlying articular cartilage damage appears similarly dichotomized (Goldring and Goldring, 2010).

Bone Morphology

As a dynamic scaffold to the musculoskeletal system, abnormalities in bone morphology that lead to altered biomechanics are now well recognized in disease initiation (Ganz et al., 2008). Increased acetabular anteversion, femoral head asphericity, femoral head–neck junction deformity, and the “cam” and “pincer” features of femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) have all been linked to an increased risk of developing osteoarthritis (Figure 2; Tönnis and Heinecke, 1999; Doherty et al., 2008; Ganz et al., 2008; Barros et al., 2010).

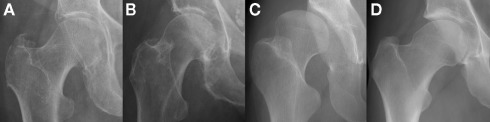

Figure 2.

Morphological abnormalities of the hip joint associated with hip osteoarthritis that have been demonstrated with plain radiography: (A) femoral head tilt with reduced acetabular anteversion which can lead to excessive anterior acetabular coverage; (B) pistol grip deformity with lack of femoral head sphericity that can lead to impingement at the superolateral articular cartilage; (C) developmental dysplasia of the hip with excessive acetabular anteversion that results in globally deranged biomechanics; (D) the osseous bump “cam” deformity associated with FAI which also can lead to impingement at the anterior articular cartilage. Images courtesy of the Department of Radiology, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge.

Although FAI is a relative newcomer as an etiological concept (Figure 3), researchers have been aware of aspects of these morphological features for decades (Solomon, 1976). The majority of bone morphometry continues to be performed on plain radiographs (Figure 2), with emphasis on assessing deformity secondary to osteoarthritis for arthroplasty planning rather than describing primary deformities that may predispose to osteoarthritis for prognostic evaluation (Gregory et al., 2007).

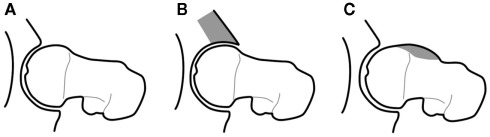

Figure 3.

Diagrammatic representation of the morphological variants implicated in FAI that lead to increased stress on articular cartilage, prompting premature breakdown of the normal joint homeostasis and early development of OA: (A) normal; (B) “pincer” deformity of the anterior acetabulum; (C) “cam” deformity of the anterior femoral head–neck junction, after Tannast et al. (2007).

Osteophytes

Osteophytes are metaplastic osteo-cartilagenous tissues that form at the margins of osteoarthritic joints. They have long been recognized as a key bony contingent of the disease process (Jeffery, 1973), however their precise function in pathogenesis is still unclear and continues to warrant further investigation (Menkes and Lane, 2004). One of the key issues yet to be settled is whether osteophytes occur as a response to altered joint mechanics and instability (and are thus an attempt at re-stabilization) or whether they are an undesired side-effect of the anabolic response to an altered joint milieu that promotes chondrogenesis (van der Kraan and van den Berg, 2007).

According to one previous radiographic study, the presence or absence of osteophytes also appeared to define two distinct disease phenotypes – hypertrophic and atrophic osteoarthritis respectively – which raises the question as to why individuals with osteoarthritis develop osteophytes not only in different distributions, but also to differing extents (Figure 4; Ledingham et al., 1992). Another radiographic–histological study described three main distributions of femoral head osteophytes – epiarticular, marginal, and subarticular – that were each associated with specific patterns of joint degeneration (Jeffery, 1973).

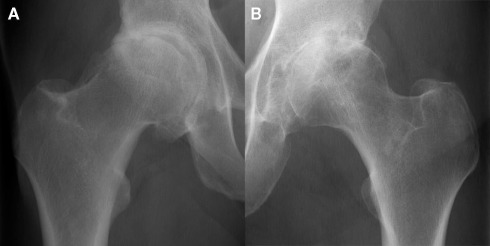

Figure 4.

Radiographically moderate osteoarthritis in hypertrophic (A) and atrophic (B) forms. Images courtesy of the Department of Radiology, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge.

These variations have not been fully investigated and further examination of the relationship between osteophytes, joint morphology, and the other features of osteoarthritis could provide fundamental insights into pathogenesis at the whole organ and cellular levels. In fact, one recent study showed that there was no relationship between bone mineral density and the presence of osteophytes in hip osteoarthritis and called for such further investigation into the relationship of osteophytes and hip morphology (Okano et al., 2011).

Imaging Bone in Hip Osteoarthritis

Imaging is a vital component of in vivo and ex vivo/in vitro osteoarthritis research, with the majority of activity having implemented magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to focus on articular cartilage and/or plain radiography to screen for disease and grade and severity (Kellgren and Lawrence, 1957; Hayashi et al., 2011). While plain radiography is cheap, quick, and available and MRI is a technique that is excellent at depicting the subchondral bone marrow lesions found in osteoarthritis (Roemer et al., 2009), both have drawbacks in the assessment of bone related to osteoarthritis.

Plain Radiography

During the decades prior to the widespread application of MRI, radiographs were the mainstay of osteoarthritis imaging in research and clinical practice. The first published description of osteoarthritis grading was provided by Kellgren and Lawrence (1957) and although a few competing radiographic grading systems have been introduced since, it remains one of the favored methods (Kellgren and Lawrence, 1957; Tönnis, 1976; Croft et al., 1990; Reijman et al., 2004). This is also despite the fact that it is essentially an objective non-quantitative system that has suffered from the obfuscating effect of a number of different descriptions being applied to assign a grade score (Schiphof et al., 2008).

As we have seen, plain radiographs remain important in the assessment of osteoarthritis and have been used in research for the assessment of bone morphology and osteophyte distribution (Figures 2 and 4). However, one of the biggest limitations with respect to modern imaging is that the processes inherent to radiography project a 3D structure as a single 2D representation, in doing so losing important spatial and morphological information.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

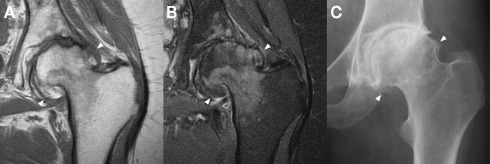

Thanks to its multi-planar capability, the ability to visualize multiple tissue pathologies and the lack of ionizing radiation, MRI remains the most important imaging technique in osteoarthritis (Guermazi et al., 2011). Cortical bone and the subchondral bone plate are high-density materials with low signal characteristics on nearly all imaging sequences, while red or yellow marrow signal usually predominates over trabecular architecture in medullary bone (Figure 5). The relatively poor spatial resolution of MRI compared to other imaging modalities, the occurrence of imaging artifacts and the lack of specificity of such signal characteristics to bone do limit its value: for example, fibrous tissue and metal susceptibility artifact are usually also low signal, while the fluid signal of bone marrow lesions can be seen in pathologies other than osteoarthritis. The full extent of osteophytes can also be difficult to appreciate without plain radiography for correlation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Marginal osteophytes in a left hip with moderate osteoarthritis as seen with a coronal T1 sequence (A), a coronal proton density fat saturation sequence (B), and plain radiography (C). Marginal osteophytes (arrowheads) are identifiable in all three, but MRI lacks accurate bony definition, while plain radiography lacks useful 3D information. Both can underestimate the extent of osteophytosis. Images courtesy of the Department of Radiology, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge.

The development of MRI at increased magnetic field strengths (3T and subsequently 7T) has improved spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, but this is at the cost of increased metal susceptibility and chemical shift artifacts. The latter is an important consideration in relation to bone because of the presence of fat, the subject of this artifact, in yellow bone marrow (Soher et al., 2007). Nonetheless, promising developments in high field strength imaging have enabled accurate depiction of trabecular bone micro-architecture at 7T (Chang et al., 2008). One 3T MRI study looking at the relationship between trabecular bone and articular cartilage characteristics suggested that overall loss of mineralized bone volume was related to cartilage degeneration (Bolbos et al., 2008). Another advance has been the application of ultrashort echo time MRI sequences that are in development for the visualization of cortical bone with higher spatial resolution and contrast than conventional sequences (Du et al., 2010). A distinguishing feature of this technique is that cortical bone has high rather than the usual low signal. With the significant advantage of being able to simultaneously image bone and cartilage, MRI clearly has a developing role to play in the imaging of bone in osteoarthritis, but does come with limitations.

Computed Tomography

Despite the fact that one study comparing CT with MRI in the assessment of osteoarthritis severity favored the latter on account of greater sensitivity, the role of CT in osteoarthritis research deserves to be reassessed (Chan et al., 1991). It can provide superior information about bone structure, including joint morphology and standard morphometric parameters such as bone volume fraction and trabecular thickness (Sariali et al., 2009; Chiba et al., 2011). CT arthrography, although limited in its application from being an invasive procedure, has also been used in the assessment of the joint space and articular cartilage and is important clinical alternative when MRI is contra-indicated (Alvarez et al., 2005).

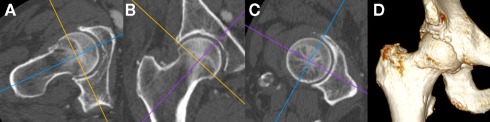

In line with technological advances, MDCT now allows for multi-planar reformatting and 3D reconstruction of bony surfaces (Figure 6), which not only circumvent cumbersome steps required in early CT analysis (e.g., scanning in the prone position to align the pelvis in the correct plane; Tönnis and Heinecke, 1999), but also provide 3D morphological and topographic information as a platform for further analysis (see below). This use of 3D information engenders the same principle behind volumetric bone mineral density calculation performed with quantitative CT as opposed to areal bone mineral density as calculated by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA; Lang, 2010), namely the ability to take into account a volume of tissue rather than an area. The correct application of CT could therefore result in detection of disease features such as subchondral bone plate density change, subchondral cyst formation, and osteophyte development at much earlier stages than plain radiography.

Figure 6.

Multi-detector CT multi-planar reformatting of the right hip viewed with a bone window (A) in the axial oblique, (B) coronal oblique, and (C) sagittal oblique planes with respect to the long axis of the femoral head and neck; (D) Shaded surface display 3D reconstruction of the same individual. Note the presence of degenerative osteophytes at the anterior femoral head–neck junction in (A,D), early marginal osteophytes at the superior and inferior femoral head–neck junction in (B) and irregularity of the acetabular rim throughout. Images courtesy of the Department of Radiology, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge.

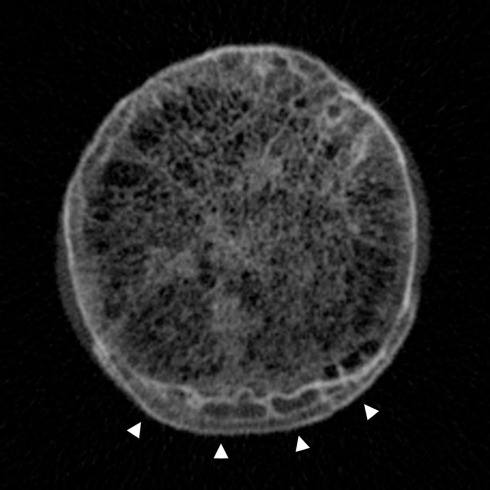

What’s more, CT should be able to provide this information at increasingly lower radiation doses (Tamm et al., 2011), with novel techniques for dose reduction being continually developed – such as multiple low dose acquisitions (Hulme et al., 2011). However it should be remembered that at a typical effective dose of around 1–3 mSv, MDCT for the purposes of bone structure and density analysis is a far greater radiation burden than DEXA at around 0.01 mSv per examination (the worldwide average effective background dose being 2.4 mSv/year; Damilakis et al., 2010). On the back of this, there is a strong epidemiological argument for using CT data in the assessment of hip osteoarthritis, because a huge number of examinations that cover the hip joints are performed every day for alternative indications: here is a wealth of potentially diagnostic and prognostic information that remains untapped. Free from the constraints of radiation load, high-resolution CT can also be used to image ex vivo specimens, for example in cadavers or in samples taken from individuals with osteoarthritis who have had their joint replaced (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Cadaveric high-resolution CT image across the femoral head–neck junction showing the trabecular bone network centrally and the distinctive pattern of cortical–trabecular–cortical bone in marginal osteophytes at the inferior aspect (arrowheads). Image by Dr Paul Mayhew, from a Densiscan 1000 peripheral Quantitative CT Scanner, Scanco AG Switzerland. Specimen courtesy of Professor John Clement, Melbourne Femur collection (Melbourne Dental School, Australia).

This is an excellent opportunity to provide comprehensive 3D micro- and macroscopic structural information about the hip for the purposes of diagnosis and prognostication. While there has been work on plain radiographs using active shape modeling to determine important modes of shape variation in the proximal femur in relation to the risk of incident radiographic hip osteoarthritis (Lynch et al., 2009), no published studies have yet looked at the value of CT in determining morphological predispositions to osteoarthritis or its relationship with volumetric bone mineral density. Furthermore, although no validated CT grading system of osteoarthritis currently exists, CT could easily be used to image its bony features, potentially setting a new standard for grading in epidemiological research and clinical trials.

Osteophyte structure and distribution are prime examples of bony features in osteoarthritis that would be suitable for analysis with CT, which (although already performed in part for elbow osteoarthritis) to the best of our knowledge has not yet been done in human hip osteoarthritis (Lim et al., 2008). The relationships between osteophyte distribution, morphology, and deformity have been examined with plain radiography, but again there have been no published studies to date that have used CT to further investigate (Jeffery, 1973).

As with other imaging modalities, there are limitations to CT such as poor visualization of articular and peri-articular soft tissue structures and some pathological features such as bone marrow lesions; imaging with MRI is superior in such instances. However, one of the most exciting developments afforded by the application of CT imaging to osteoarthritis research takes advantage of its accurate depiction of bone and multi-planar capability, reprocessing imaging data with promising effects.

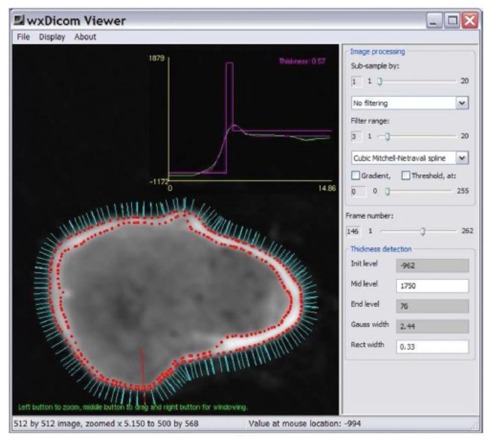

Computational Analysis

Computational analysis techniques are powerful tools that can be used to assess bony features of the hip joint such as bone thickness and morphology by creating virtual 3D imaging data from 2D CT acquisitions. A recently developed technique can estimate the cortical thickness of the proximal femur from CT data at multiple surface normal points by assuming a standardized CT attenuation value of cortical bone (Figure 8). One of the most important aspects of this technique is that cortical thickness can be accurately modeled from clinical CT data (for example with a slice thickness of 1 mm) down to a sub-pixel resolution of 0.3 mm (Treece et al., 2010). Cortical bone beneath articular cartilage is equivalent to subchondral bone and so this can be applied to measure thickness of the subchondral bone plate.

Figure 8.

Surface normals (cyan) around the neck of the right femur (imaged with CT), each of which can be used as a point for cortical thickness measurement; a single measurement is made at the point of the red line and displayed as the magenta peak in the graph above (0.57 mm). Image courtesy of Dr. Graham Treece, Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge.

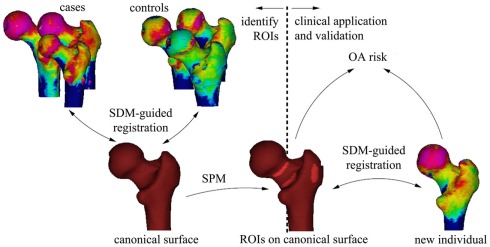

Statistical parametric mapping (SPM) can then be used to compare subchondral bone thickness from case and control subjects, using methods which account for inter-individual variability in shape using statistical deformation modeling (SDM; Rueckert et al., 2003). SPM generates regions of interest (ROIs) that represent significantly different thicknesses of bone between cases and controls. As long as cases are selected on clinically relevant criteria (for instance hip pain or eventual joint replacement in longitudinal studies), the ROIs are ideally suited for taking forward into prospective, outcome driven research. If the ROIs have merit in predicting incident, clinically relevant osteoarthritis, then individual patients can be easily tested against population averages and disease-specific criteria (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The process of using SPM to establish ROIs that represent significant sites of cortical thinning that through clinical application and validation could be used to assess for the risk of osteoarthritis in a new individual. Image courtesy of Dr. Graham Treece, Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge.

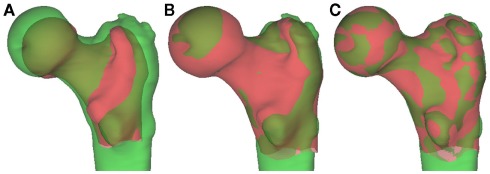

Using a technique called B-spline free-form deformation, it is possible to smoothly warp the virtual surface of a standardized “canonical” femur in an iterative process to match with a test subject (Figure 10). The most important modes of variation (usually the top 10%) can be established through principle component analysis (PCA; Rueckert et al., 2003). These can then be correlated with important clinical and radiological features of osteoarthritis, making it possible to establish modes that can predict osteoarthritis disease and progression.

Figure 10.

Shape manipulation with B-spline deformation. (A) The “canonical” proximal femur (red) and the test femur (green) are overlaid. (B) The “canonical” femur is changed in scale and position to approximate a best fit. (C) The “canonical” femur is warped through B-spline deformation to fit the test femur, giving “modes” of variation ranked according to importance with PCA. Image courtesy of Dr. Graham Treece, Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge.

This was recently successfully performed by Poole et al. (2011) to determine an increased risk of femoral neck fracture from specific sites of cortical thinning in the femoral neck and, given our developing understanding of the importance of changes in subchondral bone in osteoarthritis, could be translated to assessing for risk of osteoarthritis development and progression. The thickness measurement technique could also be developed to assess radiological features of the disease such as osteophyte patterning and, in combination with the acetabulum, joint space width as novel imaging biomarkers.

Another promising computational modeling technique that uses CT imaging data has been developed in collaboration between engineers and radiologists in Iowa, USA. This has just recently been published, emphasizing the developing importance of such techniques and collaborations within osteoarthritis research. Their algorithm uses active shape modeling (which can be used to perform segmentation) for defining osteophyte growth in the knees of rabbits with surgically induced osteoarthritis, showing it to be highly accurate, reproducible, and sensitive in detecting disease progression (Saha et al., 2011). As of yet, no such studies have been performed in humans.

Relating to Cellular and Molecular Aspects of Hip Osteoarthritis

Our current understanding of osteophytes suggests that they originate from precursor cells in bone periosteum and that their induction is heavily influenced by the TGFβ superfamily and bone morphogenetic proteins (van der Kraan and van den Berg, 2007). Dickkopf-1 (Dkk1) has also been suggested as having a role in preventing osteophyte formation in arthritis by adjusting joint homeostasis toward dampened anabolic repair and promoting catabolic destruction (Diarra et al., 2007). Detailed research has been performed into the molecular characterization of different stages of osteophyte development, with the role of sclerostin as a Wnt-signaling pathway inhibitor being well established as an anti-bone-forming molecule (Gelse et al., 2003; Alcaraz et al., 2010). Recently published work has also shown that osteocyte sclerostin expression is reduced in hip osteoarthritis, potentially mediating increased osteoblastic activity in intracapsular bone cortex (Power et al., 2010). However, it is not known what precise effects sclerostin might be having in osteoarthritis in general and osteophyte development in particular, and how this might relate to bone remodeling.

Hypertrophic and atrophic forms of osteoarthritis have been used as a basis for the comparison of cellular and biochemical aspects of the disease, with Conrozier et al. (2007) using radiographs to categorize subject groups, but this is a rare example. Accurately establishing valid disease phenotypes according to the presence and distribution of osteophytes using CT could therefore provide important insights into the disturbed biochemical homeostasis, especially in relation to morphology.

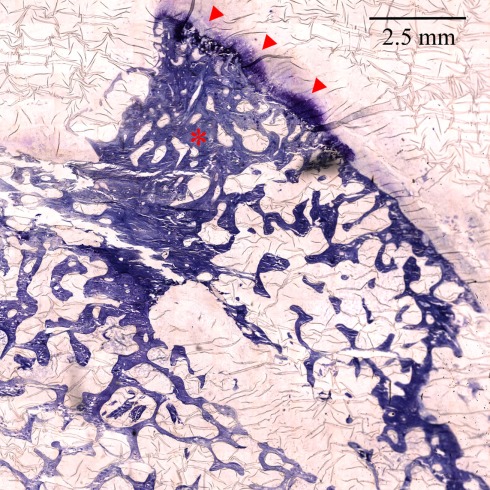

Figure 11 shows the histological appearances of an osteophyte protruding from the femoral head–neck junction, with dense trabecular bone multicellular units (BMUs) beneath a neo-cartilage cap. As we suggest, abnormal morphology and subchondral bone would be amenable to imaging analysis with CT and combining CT with macroscopic analysis of surgically excised or cadaveric samples may permit comparative studies (such as osteophyte distribution, cartilage thickness, joint space width, and subchondral cysts) in the attempt to establish a CT-based grading system of osteoarthritis. Histological analysis of underlying cartilage and bone would then be able to provide information to relate imaging to the severity of disturbed microscopic and ultra-structure.

Figure 11.

×100 Toluidine blue stained section of the femoral head–neck junction showing an osteophyte with dense trabecular BMUs (asterisk) and a cartilage cap (arrowheads). Image prepared by Dr. Linda Skingle; sections cut by Dr. Grant Jordan. Image courtesy of the Bone Research Group, University of Cambridge.

Genetic Influences

While genetic factors are recognized as a component of the multifactorial etiology of osteoarthritis, establishing their direct influence has proved testing, possibly because the process seems to involve multiple loci, each of which have only a small effect. The majority of genetic studies in osteoarthritis have focused on the knee, for example with Neame et al. (2004) estimating a heritability of 0.62 for knee osteoarthritis in their woman sibling study. One large meta-analysis combining over 8000 patients confirmed that the 7q22 chromosomal region conferred a risk for knee osteoarthritis, implicating six genes with a possible role in pathogenesis, with further work yet needed to understand the molecular pathways that could be involved. The authors of this meta-analysis also suggested that, because there were a number of small genetic effects, detecting other possible associations from minor alleles could require as many as 15,000 subjects, clearly a significant research undertaking (Evangelou et al., 2011).

The genetic heterogeneity observed in osteoarthritis and the undefined chain of processes from underlying genotype through expression to phenotype makes this a challenging field in which to tease out associations, especially when they are required to meet a P value of less than 5 × 10−8 in genome-wide association studies. For these reasons, the role of genetics in determining disease predisposition remains underpowered, with its relationship with bone morphology not even yet considered. However, an accurate characterization of pre-disease structural phenotypes as well as disease pattern phenotypes in hip osteoarthritis would be an important step in determining genetic influences, especially for the new generation of suitably powered genome-wide association studies that are on the horizon (Loughlin, 2011; Meulenbelt et al., 2011).

Conclusion

Computed tomography provides excellent imaging information on bone and is ideally suited to the application of novel computational analysis techniques. In this review, we have argued that research into hip osteoarthritis will benefit enormously from a greater application of CT imaging, for example by using morphological analysis, subchondral bone plate thickness measurement, and osteophyte patterning to establish valid structural and disease phenotypes, with the positive implications that this brings for future molecular and genetic studies.

While no validated CT grading for hip osteoarthritis currently exists, given the potential for accurate and early depiction of disease features, there is also strong epidemiological argument to develop its use in the assessment of hip osteoarthritis, both clinically and in the setting of research trials.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Alcaraz M. J., Megías J., García-Arnandis I., Clérigues V., Guillén M. I. (2010). New molecular targets for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 13–21 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez C., Chicheportiche V., Lequesne M., Vicaut E., Laredo J.-D. (2005). Contribution of helical computed tomography to the evaluation of early hip osteoarthritis: a study in 18 patients. Joint Bone Spine 72, 578–584 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros H. J. M., Camanho G. L., Bernabé A. C., Rodrigues M. B., Leme L. E. G. (2010). Femoral head-neck junction deformity is related to osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 468, 1920–1925 10.1007/s11999-010-1328-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolbos R. I., Zuo J., Banerjee S., Link T. M., Ma C. B., Li X., Majumdar S. (2008). Relationship between trabecular bone structure and articular cartilage morphology and relaxation times in early OA of the knee joint using parallel MRI at 3T. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 16, 1150–1159 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botter S. M., Glasson S. S., Hopkins B., Clockaerts S., Weinans H., van Leeuwen J. P. T. M., van Osch G. J. V. M. (2009). ADAMTS5−/− mice have less subchondral bone changes after induction of osteoarthritis through surgical instability: implications for a link between cartilage and subchondral bone changes. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 17, 636–645 10.1016/j.joca.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W. P., Lang P., Stevens M. P., Sack K., Majumdar S., Stoller D. W., Basch C., Genant H. K. (1991). Osteoarthritis of the knee: comparison of radiography, CT, and MR imaging to assess extent and severity. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 157, 799–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang G., Pakin S. K., Schweitzer M. E., Saha P. K., Regatte R. R. (2008). Adaptations in trabecular bone microarchitecture in olympic athletes determined by 7T MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 27, 1089–1095 10.1002/jmri.21326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba K., Ito M., Osaki M., Uetani M., Shindo H. (2011). In vivo structural analysis of subchondral trabecular bone in osteoarthritis of the hip using multi-detector row CT. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 180–185 10.1016/S1063-4584(11)60418-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrozier T., Ferrand F., Poole A. R., Verret C., Mathieu P., Ionescu M., Vincent F., Piperno M., Spiegel A., Vignon E. (2007). Differences in biomarkers of type II collagen in atrophic and hypertrophic osteoarthritis of the hip: implications for the differing pathobiologies. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15, 462–467 10.1016/j.joca.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft P., Cooper C., Wickham C., Coggon D. (1990). Defining osteoarthritis of the hip for epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 132, 514–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais S., Garbedian S., Wai E. K. (2009). Systematic review of the prevalence of radiographic primary hip osteoarthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 467, 623–637 10.1007/s11999-008-0625-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damilakis J., Adams J. E., Guglielmi G., Link T. M. (2010). Radiation exposure in X-ray based imaging techniques used in osteoporosis. Eur. Radiol. 20, 2707–2714 10.1007/s00330-010-1845-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J. S., Ding M., van der Linden J. C., Hvid I., Sumner D. R., Weinans H. (2001). A decreased subchondral trabecular bone tissue elastic modulus is associated with pre-arthritic cartilage damage. J. Orthop. Res. 19, 914–918 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00012-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dequeker J., Luyten F. P. (2008). The history of osteoarthritis-osteoarthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, 5–10 10.1136/ard.2007.079764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diarra D., Stolina M., Polzer K., Zwerina J., Ominsky M. S., Dwyer D., Kord A., Smolen J., Hoffmann M., Schneinecker C., van der Heidi D., Landewe R., Lacey D., Richards W. G., Schett G. (2007). Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodelling. Nat. Med. 13, 156–163 10.1038/nm1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieppe P. A., Lohmander L. S. (2005). Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet 365, 965–973 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71086-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty M., Courtney P., Doherty S., Jenkins W., Maciewicz R. A., Muir K., Zhang W. (2008). Nonspherical femoral head shape (pistol grip deformity), neck shaft angle, and risk of hip osteoarthritis: a case-control study. Arthritis Rheum. 58, 3172–3182 10.1002/art.23939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore D., Quinn S., Ding C., Winzenberg T., Jones G. (2009). Correlates of subchondral BMD: a cross-sectional study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 2007–2015 10.1359/jbmr.090532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Carl M., Bydder M., Takahashi A., Chiung C. B., Bydder G. M. (2010). Qualitative and quantitative ultrashort echo time (UTE) imaging of cortical bone. J. Magn. Reson. 207, 304–311 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelou E., Valdes A. M., Kerkhof H. J. M., Styrkarsdottir U., Zhu Y., Meulenbelt I., Lories R. J., Karassa F. B., Tylzanowski P., Bos S. D., arcOGEN Consortium. Akune T., Arden N. K., Carr A., Chapman K., Cupples L. A., Dai J., Deloukas P., Doherty M., Doherty S., Engstrom G., Gonzalez A., Halldorsson B. V., Hammond C. L., Hart D. J., Helgadottir H., Hofman A., Ikegawa S., Ingvarsson T., Jiang Q., Jonsson H., Kaprio J., Kawaguchi H., Kisand K., Kloppenburg M., Kujala U. M., Lohmander L. S., Loughlin J., Luyten F. P., Mabuchi A., McCaskie A., Nakajima M., Nilsson P. M., Nishida N., Ollier W. E., Panoutsopoulou K., van de Putte T., Ralston S. H., Rivadeneira F., Saarela J., Schulte-Merker S., Shi D., Slagboom P. E., Sudo A., Tamm A., Tamm A., Thorleifsson G., Thorsteinsdottir U., Tsezou A., Wallis G. A., Wilkinson J. M., Yoshimura N., Zeggini E., Zhai G., Zhang F., Jonsdottir I., Uitterlinden A. G., Felson D. T., van Meurs J. B., Stefansson K., Ioannidis J. P., Spector T. D., Translation Research in Europe Applied Technologies for Osteoarthritis (TreatOA) (2011). Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies confirms a susceptibility locus for knee osteoarthritis on chromosome 7q22. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70, 349–355 10.1136/ard.2010.132787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R., Leunig M., Leunig-Ganz K., Harris W. H. (2008). The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: an integrated mechanical concept. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 466, 264–272 10.1007/s11999-007-0060-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelse K., Söder S., Eger W., Diemtar T., Aigner T. (2003). Osteophyte development–molecular characterization of differentiation stages. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 11, 141–148 10.1053/joca.2002.0873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring M. B., Goldring S. R. (2007). Osteoarthritis. J. Cell. Physiol. 213, 626–634 10.1002/jcp.21258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring M. B., Goldring S. R. (2010). Articular cartilage and subchondral bone in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1192, 230–237 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory J. S., Waarsing J. H., Day J., Pols H. A., Reijman M., Weinans H., Aspden R. M. (2007). Early identification of radiographic osteoarthritis of the hip using an active shape model to quantify changes in bone morphometric features: can hip shape tell us anything about the progression of osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 56, 3634–3643 10.1002/art.22982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guermazi A., Roemer F. W., Hayashi D. (2011). Imaging of osteoarthritis: update from a radiological perspective. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 23, 484–491 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayami T., Pickarski M., Wesolowski G. A., McLane J., Bone A., Destefano J., Rodan G. A., Duong L. T. (2004). The role of subchondral bone remodeling in osteoarthritis: Reduction of cartilage degeneration and prevention of osteophyte formation by alendronate in the rat anterior cruciate ligament transection model. Arthritis Rheum. 50, 1193–1206 10.1002/art.20124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi D., Guermazi A., Hunter D. J. (2011). Osteoarthritis year 2010 in review: imaging. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 354–360 10.1016/j.joca.2011.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Beaumont G., Roman-Blas J. A., Castañeda S., Jimenez S. A. (2009). Primary osteoarthritis no longer primary: three subsets with distinct etiological, clinical, and therapeutic characteristics. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 39, 71–80 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme K. W., Rong J., Chasen B., Chuang H. H., Cody D. D., Wong F. C., Kappadath S. C. (2011). A CT acquisition technique to generate images at various dose levels for prospective dose reduction studies. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 196, W144–W151 10.2214/AJR.10.4470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson T. (2000). Prevalence and inheritance of hip osteoarthritis in Iceland. Acta Orthop. Scand. Suppl. 298, 1–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery A. K. (1973). Osteogenesis in the osteoarthritic femoral head. A study using radioactive 32 P and tetracycline bone markers. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 55, 262–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellgren J. H., Lawrence J. S. (1957). Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 16, 494–502 10.1136/ard.16.4.511-c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan Tat S., Lajeunesse D., Pelletier J.-P., Martel-Pelletier J. (2010). Targeting subchondral bone for treating osteoarthritis: what is the evidence? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 24, 51–70 10.1016/j.berh.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N. E. (2007). Clinical practice. Osteoarthritis of the hip. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1413–1421 10.1056/NEJMcp071112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T. F. (2010). Quantitative computed tomography. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 48, 589–600 10.1016/j.rcl.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledingham J., Dawson S., Preston B., Milligan G., Doherty M. (1992). Radiographic patterns and associations of osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 51, 1111–1116 10.1136/ard.51.10.1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y. W., van Riet R. P., Mittal R., Bain G. I. (2008). Pattern of osteophyte distribution in primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 17, 963–966 10.1016/j.jse.2008.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin J. (2011). Genetics of osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 23, 479–483 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283493ff0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J. A., Parimi N., Chaganti R. K., Nevitt M. C., Lane N. E. (2009). The association of proximal femoral shape and incident radiographic hip OA in elderly women. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 17, 1313–1318 10.1016/S1063-4584(09)60433-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannoni A., Briganti M. P., Di Bari M., Ferrucci L., Costanzo S., Serni U., Masotti G., Marchionni N. (2003). Epidemiological profile of symptomatic osteoarthritis in older adults: a population based study in Dicomano, Italy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62, 576–578 10.1136/ard.62.6.576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkes C. J., Lane N. E. (2004). Are osteophytes good or bad? Osteoarthr. Cartil. 12, S53–S54 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenbelt I., Kraus V. B., Sandell L. J., Loughlin J. (2011). Summary of the OA biomarkers workshop 2010 – genetics and genomics: new targets in OA. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 19, 1091–1094 10.1016/j.joca.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neame R. L., Muir K., Doherty S., Doherty M. (2004). Genetic risk of knee osteoarthritis: a sibling study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, 1022–1027 10.1136/ard.2004.020727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neogi T., Felson D., Niu J., Lynch J., Nevitt M., Guermazi A., Roemer F., Lewis C. E., Wallace B., Zhang Y. (2009). Cartilage loss occurs in the same subregions as subchondral bone attrition: a within-knee subregion-matched approach from the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 61, 1539–1544 10.1002/art.24824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano K., Aoyagi K., Chiba K., Motokawa S., Matsumoto T. (2011). Bone mineral density is not related to osteophyte formation in osteoarthritis of the hip. J. Rheumatol. 38, 358–361 10.3899/jrheum.100533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra D., Sandell L. J. (2011). Recent advances in biomarkers in osteoarthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 23, 465–470 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349a32b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. E. S., Treece G. M., Ridgway G. R., Mayhew P. M., Borggrefe J., Gee A. H. (2011). Targeted regeneration of bone in the osteoporotic human femur. PLoS ONE 6, e16190. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power J., Poole K. E. S., van Bezooijen R., Doube M., Caballero-Alías A. M., Lowik C., Papapoulos S., Reeve J., Loveridge N. (2010). Sclerostin and the regulation of bone formation: effects in hip osteoarthritis and femoral neck fracture. J. Bone Miner. Res. 25, 1867–1876 10.1002/jbmr.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijman M., Hazes J. M. W., Koes B. W., Verhagen A. P., Bierma-Zeinstra S. M. A. (2004). Validity, reliability, and applicability of seven definitions of hip osteoarthritis used in epidemiological studies: a systematic appraisal. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, 226–232 10.1136/ard.2003.016477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer F. W., Frobell R., Hunter D. J., Crema M. D., Fischer W., Bohndorf K., Guermazi A. (2009). MRI-detected subchondral bone marrow signal alterations of the knee joint: terminology, imaging appearance, relevance and radiological differential diagnosis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 17, 1115–1131 10.1016/j.joca.2008.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueckert D., Frangi A. F., Schnabel J. A. (2003). Automatic construction of 3-D statistical deformation models of the brain using nonrigid registration. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 22, 1014–1025 10.1109/TMI.2003.815865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P. K., Liang G., Elkins J. M., Coimbra A., Duong L. T., Williams D. S., Sonka M. (2011). A new osteophyte segmentation algorithm using partial shape model and its applications to rabbit femur anterior cruciate ligament transection via micro-CT imaging. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1109/TBME.2011.2129519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels J., Krasnokutsky S., Abramson S. B. (2008). Osteoarthritis: a tale of three tissues. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 66, 244–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariali E., Mouttet A., Pasquier G., Durante E. (2009). Three-dimensional hip anatomy in osteoarthritis. Analysis of the femoral offset. J. Arthroplasty 24, 990–997 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiphof D., Boers M., Bierma-Zeinstra S. M. A. (2008). Differences in descriptions of Kellgren and Lawrence grades of knee osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67, 1034–1036 10.1136/ard.2007.079020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soher B. J., Dale B. M., Merkle E. M. (2007). A review of MR physics: 3T versus 1.5T. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 15, 277–290 10.1016/j.mric.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon L. (1976). Patterns of osteoarthritis of the hip. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 58, 176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm E. P., Rong X. J., Cody D. D., Ernst R. D., Fitzgerald N. E., Kundra V. (2011). Quality initiatives: CT radiation dose reduction: how to implement change without sacrificing diagnostic quality. Radiographics 31, 1823–1832 10.1148/rg.317115027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannast M., Siebenrock K. A., Anderson S. E. (2007). Femoroacetabular impingement: radiographic diagnosis – what the radiologist should know. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 188, 1540–1552 10.2214/AJR.06.0921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tönnis D. (1976). Normal values of the hip joint for the evaluation of x-rays in children and adults. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 119, 39–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tönnis D., Heinecke A. (1999). Acetabular and femoral anteversion: Relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 81, 1747–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treece G. M., Gee A. H., Mayhew P. M., Poole K. E. S. (2010). High resolution cortical bone thickness measurement from clinical CT data. Med. Image Anal. 14, 276–290 10.1016/j.media.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kraan P. M., van den Berg W. B. (2007). Osteophytes: relevance and biology. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 15, 237–244 10.1016/j.joca.2006.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]