Abstract

The pharmacological action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants may include a normalization of the decreased brain levels of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and of neurosteroids such as the progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone, which are decreased in patients with depression and posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD). The allopregnanolone and BDNF level decrease in PTSD and depressed patients is associated with behavioral symptom severity. Antidepressant treatment upregulates both allopregnanolone levels and the expression of BDNF in a manner that significantly correlates with improved symptomatology, which suggests that neurosteroid biosynthesis and BDNF expression may be interrelated. Preclinical studies using the socially isolated mouse as an animal model of behavioral deficits, which resemble some of the symptoms observed in PTSD patients, have shown that fluoxetine and derivatives improve anxiety-like behavior, fear responses and aggressive behavior by elevating the corticolimbic levels of allopregnanolone and BDNF mRNA expression. These actions appeared to be independent and more selective than the action of these drugs on serotonin reuptake inhibition. Hence, this review addresses the hypothesis that in PTSD or depressed patients, brain allopregnanolone levels, and BDNF expression upregulation may be mechanisms at least partially involved in the beneficial actions of antidepressants or other selective brain steroidogenic stimulant molecules.

Keywords: allopregnanolone, 5α-reductase type I, selective brain steroidogenic stimulants, GABAA receptors, BDNF, anxiety, aggressive behavior, PTSD

Introduction

Impaired neurosteroid biosynthesis has been associated with numerous behavioral dysfunctions, which range from anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors to aggressive behavior and changes in responses to contextual fear conditioning in rodent models of emotional dysfunction (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008; Uzunova et al., 2004, 2006; Jain et al., 2005; Martin-Garcia and Pallares, 2005; Kita and Furukawa, 2008; D’Aquila et al., 2010; Pinna, 2010). In clinical studies, decreases in the serum, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) content of neuroactive steroids, including the progesterone metabolite, allopregnanolone, which is a potent positive allosteric modulator of the action of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at GABAA receptors (Puia et al., 1990, 2003; Lambert et al., 2003, 2009; Belelli and Lambert, 2005), are associated with several psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety spectrum disorders, posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD), premenstrual dysphoric disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive aggression (Rapkin et al., 1997; Romeo et al., 1998; Uzunova et al., 1998; Bloch et al., 2000; Nappi et al., 2001; Ströhle et al., 2002; Bäckström et al., 2003; Pinna et al., 2006; Rasmusson et al., 2006; Amin et al., 2007; Marx et al., 2009; Pearlstein, 2010). Thus, endogenous allopregnanolone exerts the physiological role of regulating emotional behavior by a potentiation of the inhibitory signal of the neurotransmitter GABA at GABAA receptors that are widely distributed in the glutamatergic neurons of the cortex and limbic areas, such as the hippocampus and the amygdala.

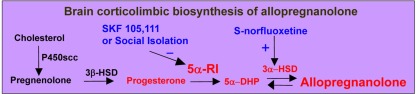

Allopregnanolone levels in the CSF of patients with PTSD and unipolar major depression were approximately half of those measured in the CSF of non-psychiatric patients (Uzunova et al., 1998; Rasmusson et al., 2006). Post-mortem studies confirmed that in depressed patients, the decrease of allopregnanolone is likely induced by a decrease in the expression of 5α-reductase type I mRNA in the prefrontal-cortex (area BA9) compared with age- and sex-matched non-psychiatric subjects (Agis-Balboa et al., 2010; for a biosynthetic representation of allopregnanolone from progesterone by the action of 5α-reductase, please see Figure 1). Our clinical studies support the hypothesis of a block in the synthesis of allopregnanolone in some individuals with PTSD and depression. This is also shown by the finding that allopregnanolone levels were the lowest among patients with comorbid PTSD and depression (Rasmusson et al., 2006). Interestingly, PTSD and major depressive disorder (MDD) are often comorbid and share multiple symptoms. Whereas PTSD is defined as a type of anxiety disorder that can occur as a result of experiencing a traumatic event that involved the threat of injury or death, several epidemiological studies show that depression diagnosed after trauma exposure is almost always comorbid with PTSD, which suggests that comorbid PTSD/MDD may likely be considered as a more severe PTSD (Breslau et al., 2002).

Figure 1.

In the brain, allopregnanolone is synthesized from progesterone by the sequential action of: (i) 5α-reductase type I (5α-RI), which reduces progesterone into 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) and functions as the rate-limiting step enzyme in allopregnanolone biosynthesis; and (ii) 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD), which either converts 5α-DHP into allopregnanolone (reductive reaction) or allopregnanolone into 5α-DHP (oxidative reaction). 17β-(N,N-diisopropylcarbamoyl)-androstan-3,5-diene-3-carboxylic acid (SKF 105,111) is a potent competitive 5α-RI inhibitor (Cheney et al., 1995). S-norfluoxetine stimulates the accumulation of allopregnanolone likely by targeting 3α-HSD (Griffin and Mellon, 1999). P450 scc, P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage; 3β-HSD, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.

In depressed patients, treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) including fluoxetine and fluvoxamine normalized CSF allopregnanolone content, which significantly correlated with the improvement in depressive symptoms (Uzunova et al., 1998). These data suggested that a deficit of GABAergic neurotransmission, likely caused by a downregulation of brain allopregnanolone biosynthesis in corticolimbic glutamatergic neurons, should be among the molecular mechanisms considered in the etiology of depression and PTSD. Upregulation of allopregnanolone biosynthesis appears to be a novel mechanism for the therapeutic effects of SSRIs (Pinna et al., 2009), at least for the anxiolytic, antidysphoric, and antiaggressive effects of these drugs. Likewise, neurosteroidogenic molecules that are unrelated to the SSRI class of drugs, including the ligands of the 18 kDa translocase protein (TSPO), which is involved in the transport of cholesterol across the inner mitochondrial membrane and activation of neurosteroidogenesis (Rupprecht et al., 2010; Schüle et al., 2011), have been recently suggested as a new class of anxiolytic drugs. These drugs exert their anxiolytic effects by increasing the brain levels of allopregnanolone but unlike benzodiazepines, are devoid of unwanted side effects, including sedation, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms (Serra et al., 1999; Rupprecht et al., 2009; Schüle et al., 2011). The advantage of a new generation of non-benzodiazepine anxiolytics for the treatment of PTSD patients lies in the finding that PTSD patients fail to respond to the pharmacological effects of anxiolytic benzodiazepines (Gelpin et al., 1996; Viola et al., 1997; Davidson, 2004).

Interestingly, parallel investigations by several other laboratories have observed that in clinical studies, the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) appears to play an important role in several psychiatric disorders, including PTSD and depression. BDNF plays a pivotal physiological role by maintaining trophism in the adult brain, affecting dendritic spine morphology, branching and synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation (LTP) with important implications for learning and memory and emotional behavior (Egan et al., 2003; Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). BDNF expressed in cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons can be released in the surrounding neuropil around cell bodies and dendrites and thus, becomes available for local utilization (Wetmore et al., 1994). The synthesis and release of BDNF by these pyramidal neurons provides evidence for both a paracrine and an autocrine role for BDNF and establishes a local source of trophic support for the maintenance of synaptic plasticity in the mature brain (Wetmore et al., 1994; Waterhouse and Xu, 2009; Cowansage et al., 2010). Because of these characteristics, BDNF may play an important role in the adaptation of corticolimbic areas to stress and to the action of antidepressants.

In psychiatric patients, BDNF expression was indeed decreased in both the post-mortem brain and in the blood cells of depressed patients. Further, the extent of BDNF downregulation positively correlated with the severity of depressive symptoms (Karege et al., 2002, 2005; Gonul et al., 2005; Piccinni et al., 2008). The levels of BDNF in the post-mortem brain of depressed patients were elevated in antidepressant-treated subjects (Chen et al., 2001; Aydemir et al., 2005; Gonul et al., 2005; Brunoni et al., 2008; Piccinni et al., 2008; Sen et al., 2008; Matrisciano et al., 2009). BDNF expression was also increased when patients were subjected to transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, or electroconvulsive therapy (Bocchio-Chiavetto et al., 2006; Lang et al., 2006).

In protracted stress rodent studies, neurotrophins including BDNF have been identified as neuroendocrine effectors involved in the response to stress and in the behavioral dysfunction associated with anxiety and depression. Protracted stress in rodents induces morphological changes, such as decreased neurogenesis and neuronal atrophy (Sapolsky, 2000; McEwen et al., 2002; Duman, 2004; Tsankova et al., 2006). Social deprivation, a condition lacking social stimuli, for instance might represent a stressful condition triggering the emergence of dysfunctional emotional behavior characterized by increased emotionality and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity in addition to reduced BDNF levels (Berry et al., 2011). Several antidepressant treatments have been shown to increase BDNF levels in the brain. Interestingly, antidepressant normalization of the stress-induced decrease of BDNF in mouse models appeared to be associated with long-term treatment with antidepressants (Nibuya et al., 1995; Shirayama et al., 2002; Russo-Neustadt et al., 2004; Alfonso et al., 2006). Of note, BDNF infusion into the hippocampus induces antidepressant-like effects in animal models of depression (Shirayama et al., 2002). On the other hand, mice lacking BDNF fail to respond to antidepressants (Monteggia et al., 2004).

Meanwhile, several preclinical studies observed that fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and other SSRIs increase the content of allopregnanolone in various rodent brain areas (Uzunov et al., 1996). Using the socially isolated mouse model of behavioral deficits that resemble symptoms of human anxiety disorders and PTSD (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004; reviewed in Pinna et al., 2006; Pinna, 2010 and Pinna et al., 2009), we have shown that corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels are decreased in association with the development of anxiety-like behaviors, resistance to sedation, and heightened aggression (Pinna et al., 2003, 2006; Nin et al., 2011). Several reports on the mechanisms by which SSRIs increase allopregnanolone biosynthesis confirmed the hypothesis that the behavioral effects of fluoxetine were unrelated to the serotonin reuptake inhibitory activity of these drugs (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004, 2009).

This review will examine whether neurosteroidogenesis and BDNF expression are interrelated and whether by elevating allopregnanolone biosynthesis, antidepressant therapy regulates BDNF expression.

Allopregnanolone and BDNF Biosynthesis and Action in Corticolimbic Neurons

Independent of peripherally-derived progestins, allopregnanolone may be synthesized in the brain (Baulieu, 1981; Cheney et al., 1995; Baulieu et al., 2001; Guidotti et al., 2001; Stoffel-Wagner, 2001) from progesterone by the sequential action of two enzymes: 5α-reductase type I, which reduces progesterone to 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP), and is the rate-limiting step enzyme in allopregnanolone biosynthesis (Figure 1); and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD), which either converts 5α-DHP into allopregnanolone (reductive reaction) or allopregnanolone into 5α-DHP (oxidative reaction; Figure 1).

Allopregnanolone reaches physiologically relevant levels that modulate GABAA receptor neurotransmission (Puia et al., 1990, 1991, 2003; Majewska, 1992; Pinna et al., 2000; Lambert et al., 2003, 2009; Belelli and Lambert, 2005). Allopregnanolone potently (nM affinity) induces a positive allosteric modulation of the action of GABA at GABAA receptors (Puia et al., 1990, 1991; Lambert et al., 2003, 2009). The physiological relevance of endogenous allopregnanolone is underlined by its facilitation and fine-tuning of the efficacy of direct GABAA receptor activators and positive allosteric modulators of GABA effects at GABAA receptors (Pinna et al., 2000; Guidotti et al., 2001; Matsumoto et al., 2003; Puia et al., 2003).

Allopregnanolone potentiates GABA responses via two binding sites in the GABAA receptor that, respectively, mediate the potentiation and direct activation effects of allopregnanolone. Direct GABAA receptor activation is initiated by the binding of allopregnanolone at a site formed by interfacial residues between the α and β subunits (Hosie et al., 2006). Binding of allopregnanolone at the potentiation site located in a cavity within the α-subunit results in a marked enhancement of GABAA receptor activation (Hosie et al., 2006).

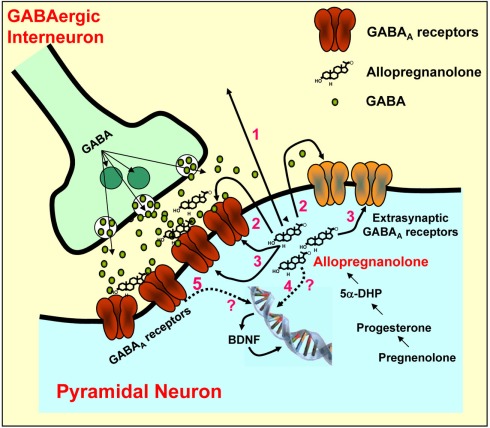

The localization of enzymes involved in allopregnanolone biosynthesis in the brain remained unclear until recent investigations in the mouse (Agis-Balboa et al., 2006, 2007; reviewed in Pinna et al., 2008). In our studies, 5α-reductase and 3α-HSD were shown to be highly expressed and colocalized in a region-specific way in primary GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons (pyramidal neurons, granular cells, reticulo-thalamic neurons, medium spiny neurons of the striatum and nucleus accumbens, and Purkinje cells), and were virtually unexpressed in GABAergic interneurons and glial cells (Agis-Balboa et al., 2006, 2007). Allopregnanolone synthesized in glutamatergic cortical or hippocampal pyramidal neurons or in granular cells of the dentate gyrus may be secreted in a paracrine manner by which allopregnanolone may reach GABAA receptors located in the synaptic membranes of other cortical or hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Figure 2, arrow 1). It could also occur in an autocrine fashion, which would allow allopregnanolone to act locally by binding post-synaptic or extra-synaptic GABAA receptors located on the same dendrites or cell bodies of the cortical or hippocampal pyramidal neuron in which allopregnanolone was synthesized (Agis-Balboa et al., 2006; Figure 2, arrow 2). Allopregnanolone might also diffuse laterally into synaptosome membranes of the cell bodies or dendritic arborization of glutamatergic neurons in which it is produced to attain intracellular access to specific neurosteroid binding sites of GABAA receptors (Akk et al., 2005; Agis-Balboa et al., 2006; Figure 2, arrow 3). Allopregnanolone and 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) may also affect intracellular signaling regulating gene expression, including BDNF expression (Figure 2, arrow 4).

Figure 2.

Allopregnanolone biosynthesis and action on GABAA receptors located on synaptic membranes of cortical pyramidal neurons. GABA, after been released from GABAergic interneurons, binds to and activates post-synaptic and extra-synaptic GABAA receptors. Allopregnanolone facilitates the synaptic inhibitory action of GABA at post-synaptic and extra-synaptic GABAA receptors by a paracrine (arrow 1) or autocrine (arrow 2) mechanism or may access GABAA receptors by acting at the intracellular sites (arrow 3) of the GABAA receptors. Finally, allopregnanolone may affect the expression of target genes, including BDNF, directly (arrow 4) or indirectly (arrow 5) by acting at GABAA receptors. BDNF may be released and induce rapid effects at synapses via altering ion channels, or may exert intracellular genomic actions. Modified from Pinna et al. (2008).

The pro- and mature-forms of BDNF are synthesized and can be released from neurons by either a constitutive secretion or activity-dependent release (Mowla et al., 1999). Mature BDNF appears to be the most abundant form and that of highest physiological significance in the adult brain (Matsumoto et al., 2008; Rauskolb et al., 2010). Also, it is widely distributed in the forebrain and in most of cortical and limbic regions, including the cortex and hippocampus (reviewed in Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). Upon release, BDNF binds to two different receptors, the tropomyosin-related kinase receptor type B (TRKB), and the p75 receptor (Soppet et al., 1991). The most widely expressed BDNF receptor across various brain areas, TRKB is considered highly significant for BDNF functional actions in adulthood due to its higher binding affinity with BDNF and brain regional distribution (reviewed in Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). On the other hand, in the adult brain the BDNF low-affinity p75 receptor is expressed in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and in a few cortical neurons (Lu et al., 1989). Interestingly, while mature BDNF binds with higher affinity to TRKB receptors, pro-BDNF has a higher affinity binding for p75 receptors. This difference in the binding of the two forms of BDNF is pivotal in terms of function. In fact, whereas the mature form of BDNF, by binding to TRKB, induces important physiological roles, including neuronal survival and the activation of several genes such as the cyclic AMP-response element-binding protein (CREB), the binding of pro-BDNF to p75 receptors has opposite effects, supporting apoptotic signaling (Koshimizu et al., 2010). The local release of BDNF in corticolimbic neurons may also regulate behavior by a rapid action on neurotransmitter systems (see also Figure 2).

Behavioral Dysfunctions Associated with Social Isolation

Exposure of mice or rats to protracted social isolation stress for 4–8 weeks induces a decrease in allopregnanolone levels in several corticolimbic structures as a result of a downregulation of the mRNA and protein expression of 5α-reductase type I (Matsumoto et al., 1999; Serra et al., 2000; Pinna et al., 2003; Bortolato et al., 2011; reviewed in Matsumoto et al., 2007; Pinna, 2010). 5α-reductase is specifically decreased in cortical pyramidal neurons of layers V–VI, in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons and glutamatergic granular cells of the dentate gyrus, and in the pyramidal-like neurons of the basolateral amygdala (Agis-Balboa et al., 2007). However, 5α-reductase fails to change in GABAergic neurons of the reticular thalamic nucleus, central amygdala, cerebellum, or in the medium spiny neurons of the caudatus and putamen (Agis-Balboa et al., 2007). The decrease of 5α-reductase in the above-mentioned brain areas resulted in a reduction of allopregnanolone levels (Pibiri et al., 2008).

Allopregnanolone biosynthesis appears to be a pivotal biomarker of behavioral deficits, including aggression, anxiety-like behavior, and changes in fear expression induced in rodent models of depression and anxiety spectrum disorders (Dong et al., 2001; Pinna et al., 2003, 2006, 2009; Uzunova et al., 2004, 2006; Pinna, 2010). In our laboratory, we have used socially isolated mice to establish an association between allopregnanolone biosynthesis and behavioral deficits as well as their reversal following pharmacological treatment (Matsumoto et al., 2003; Pinna et al., 2006, 2009; Pibiri et al., 2008; Nelson and Pinna, 2011). In mice socially isolated for a period of up to 8 weeks, we have demonstrated a time-dependent increase in aggressive behavior over the first 4 weeks of isolation accompanied by a time-dependent decrease of corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008; Pinna, 2010). Similarly, socially isolated mice exposed to a classical fear conditioning paradigm showed enhanced conditioned contextual but not explicitly cued fear responses compared with group-housed mice (Pibiri et al., 2008; Pinna et al., 2008). The time-related increase of contextual fear responses correlated with the downregulation of 5α-reductase mRNA and protein expression observed in several corticolimbic areas, such as the frontal cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala (Pibiri et al., 2008). Likewise, social isolation in mice results in anxiety-like behavior (Pinna et al., 2006; Nin et al., 2011).

Pharmacological treatment with allopregnanolone dose-dependently decreased aggression in a manner that correlated with an increase in corticolimbic allopregnanolone content (Pinna et al., 2003). These antiaggressive effects of allopregnanolone were confirmed by experiments in which allopregnanolone was directly infused into the basolateral amygdala, which increased the levels of basolateral amygdala and hippocampus allopregnanolone (Nelson and Pinna, 2011).

Allopregnanolone also normalized the exaggerated contextual fear responses and anxiety of socially isolated mice (Pibiri et al., 2008). Administration of the potent 5α-reductase competitive inhibitor SKF 105,111 to normal group-housed mice (Cheney et al., 1995; Pinna et al., 2000, 2008; Pibiri et al., 2008) rapidly (∼1 h) decreased levels of allopregnanolone in the olfactory bulb, frontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala by 80–90% (Pibiri et al., 2008; Pinna et al., 2008) in association with a dose-dependent increase of conditioned contextual fear responses (Pibiri et al., 2008). The effects of SKF 105,111 on conditioned contextual fear responses were reversed by administering allopregnanolone doses that normalized hippocampus allopregnanolone levels (Pibiri et al., 2008). The anxiolytic and antidepressant properties of allopregnanolone have been extensively documented by several other laboratories using various rodent models of abnormal behavior (Bitran et al., 1991; Wieland et al., 1991; Rodgers and Johnson, 1998; Frye and Rhodes, 2006; Engin and Treit, 2007; Nin et al., 2008; Frye et al., 2009; Deo et al., 2010).

SSRIs Act as Selective Brain Steroidogenic Stimulants and Abolish Behavioral Abnormalities

Results obtained in our laboratory have suggested that administration of a racemic mixture of the R- and S-isomers of fluoxetine induced increases in corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels and normalized the righting reflex loss induced by pentobarbital in mice (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004, 2009). Importantly, at the doses used, fluoxetine failed to change the behavior and allopregnanolone levels of group-housed mice (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004). Thus, we hypothesized that fluoxetine could ameliorate the behavioral deficits of socially isolated mice by upregulating corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels rather than by inhibiting serotonin reuptake. This hypothesis was investigated using the R- and S-stereoisomers of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine as pharmacological tools. We expected that these drugs would stereospecifically upregulate corticolimbic allopregnanolone content but have no stereoselectivity with regard to inhibition of 5-HT reuptake. Fluoxetine dose-dependently and stereospecifically normalized the duration of pentobarbital-induced sedation and reduced aggressiveness, fear responses, and anxiety-like behavior at the same submicromolar doses that normalized the downregulation of brain allopregnanolone content in socially isolated mice (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2009). Interestingly, the S-stereoisomers of fluoxetine or norfluoxetine appeared to be three-to-sevenfold more potent than their respective R-stereoisomers and S-norfluoxetine was about fivefold more potent than S-fluoxetine. Importantly, the effective concentrations (EC50s) of S-fluoxetine and S-norfluoxetine that normalize brain allopregnanolone content are 10- (S-fluoxetine) and 50-fold (S-norfluoxetine) lower than their respective EC50s needed to inhibit 5-HT reuptake (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004, 2009; Pinna, 2010). Of note, the SSRI activity of S or R-fluoxetine and of S or R-norfluoxetine was devoid of stereospecificity (Pinna et al., 2003, 2004).

These studies have clearly demonstrated that in socially isolated mice the pharmacological actions of SSRIs are induced by their ability to act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs), which suggests a novel and more selective mechanism for the behavioral action of this class of drugs.

Neurosteroids and Neurosteroidogenic Antidepressants Regulate Neurogenesis and Neuronal Survival

Adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus begins by dividing precursor cells originating in the subgranular zone (SGZ). Another brain structure characterized by intense neurogenesis is the subventricular zone (SVZ). The differentiation and integration of new neurons to the adult dentate gyrus plays an important role in plasticity and represents a fundamental step in hippocampus-dependent learning/memory processes and possibly affects emotional behavior (Deng et al., 2010).

A growing number of studies support a role for steroid hormones [progesterone, allopregnanolone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfated form DHEAS, estradiol, and androgens] in neurogenesis and cellular survival. Stem cells with multi differentiation potential for neuronal phenotypes are influenced by steroid hormones, such as regulating gene expression by binding to intracellular steroid receptors, activation of intracellular pathways involving kinases or intracellular calcium signaling, and modulation of receptors for neurotransmitters (reviewed in Velasco, 2011). Interestingly, steroid hormones can even substitute for modulate the action of growth factors and also directly influence self-renewal, proliferation, differentiation, or cell death of neurogenic stem cells.

Several environmental or internal factors affect neurogenesis in the hippocampus, among them social stress, including protracted social isolation, potently decreases neurogenesis (Dranovsky et al., 2011). Likewise, several stress-induced rodent models of depression show impaired neurogenesis (Coyle and Duman, 2003; Kempermann and Kronenberg, 2003). On the other hand, environmental enrichment, exercise, learning, and antidepressant treatments are able to increase the number, differentiation, and survival of newborn hippocampal neurons (Kempermann and Gage, 1998; van Praag et al., 1999; Leuner et al., 2004; Dranovsky and Hen, 2006). Interestingly, the pharmacological effects of neurosteroidogenic antidepressants can be abolished by reducing dentate gyrus neurogenesis (Santarelli et al., 2003; David et al., 2009), suggesting that the pharmacological effects of antidepressants may include the stimulation of neuronal progenitor cells, which has been reported in studies with rodent, human, and non-human primate hippocampus (Kempermann and Kronenberg, 2003; Boldrini et al., 2009). The adult amygdala shows signs of mixed activity-dependent plasticity with reduced numbers of microglia and a low level of proliferation and limited changes over time in neuronal and glial immunocytochemical properties (Ehninger et al., 2011). However, the basolateral amygdala seems to play a role in antidepressant-mediated hippocampal cell proliferation and survival as demonstrated by studies in rodents in which only when the basolateral amygdala was lesioned, did fluoxetine have a positive effect on hippocampal cell survival and antidepressant action (Castro et al., 2010).

Glucocorticoids have been shown to exert a primary and permissive regulatory role in hippocampal neurogenesis. Whereas stress-induced increased glucocorticoid levels reduce the proliferation of progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus, the reduction of their levels following adrenalectomy enhances neurogenesis (Wong and Herbert, 2004). DHEA and DHEAS also promote neurogenesis and neuronal survival. Given to rats, DHEA stimulated progenitor cell division and counteracted the suppressive effects of corticosterone (Karishma and Herbert, 2002). In another study, DHEA and DHEAS increased neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, likely by increasing the concentrations of BDNF. A single administration of DHEA or DHEAS changed regional brain concentrations of BDNF within 5 h (Naert et al., 2007). DHEA decreased BDNF content in the hippocampus but not in the amygdala and increased BDNF in the hypothalamus. DHEAS first decreased BDNF after 30 min post-injection and increased BDNF after 3 h in the hippocampus. A biphasic increase in BDNF in the amygdala and decreased BDNF in the hypothalamus was also reported (Naert et al., 2007). This work suggests that DHEA and DHEAS affect BDNF levels by different mechanisms with unclear effects on neurogenesis and neuronal survival. DHEAS promoted survival of adult human cortical brain tissue in vitro (Brewer et al., 2001). DHEAS was as effective as the human recombinant fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) in promoting survival of neuron-like cells. DHEAS and FGF2 were synergistic in increasing cell survival (Brewer et al., 2001). Interestingly, DHEA showed a synergistic effect with antidepressants, in fact, it can render an otherwise ineffective dose of fluoxetine capable of increasing progenitor cell proliferation to the same extent as doses four times higher, which supports a role for DHEA as a useful adjunct therapy for depression (Pinnock et al., 2009).

Progesterone and progesterone metabolites, including allopregnanolone, also play a pivotal role on neurogenesis and neuronal survival. In the dentate gyrus of adult male mice, administration of progesterone increased the number of cells by twofold, likely by enhancing cell survival of newborn neurons (Zhang et al., 2010). The effects of progesterone appeared to be partially mediated by binding to progesterone receptors, as suggested by the fact that the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride failed to prevent this effect, which was instead partially blocked by the progesterone antagonist RU486 (Zhang et al., 2010). In an in vitro study, both progesterone and allopregnanolone promoted human and rat neural progenitor cell proliferation. Allopregnanolone showed greater efficacy at the same concentration (Wang et al., 2005). In in vivo studies, allopregnanolone increased BrdU incorporation in the 3-month-old mouse hippocampal SGZ as well as in the SVZ (Brinton and Wang, 2006; Wang et al., 2010). These data suggested that for both neuroprotection and also likely for neurogenesis, allopregnanolone is the preliminary active agent. The role of allopregnanolone on neurogenesis was additionally tested on cerebellar granule cells. Allopregnanolone increased the proliferation of immature cerebellar granular cells taken from 6- to 8-day-old pups. This effect was abolished by bicuculline and picrotoxin (antagonists of GABAA receptors) and by nifedipine (dihydropyridine l-type-calcium channel blocker), which suggested that allopregnanolone increases DNA synthesis through a GABAA receptor-mediated activation (Keller et al., 2004).

Progesterone synthesized in Schwann cells also exerts important effects in the peripheral nervous system by promoting myelination, likely by an action mediated through progesterone receptors, although allopregnanolone also plays a role. Interestingly, progesterone stimulated myelin-specific proteins [e.g., protein 0 (P0) and the peripheral myelin protein-22 (PMP-22)] (Désarnaud et al., 1998; Melcangi et al., 1998, 1999; Notterpek et al., 1999) and increased the expression of Krox-20, a transcription factor crucially involved in myelination in the peripheral nervous system (Guennoun et al., 2001, reviewed in Mellon, 2007). As mentioned above, some effects on the expression of the myelin basic protein were likely mediated through allopregnanolone, as demonstrated by a study in which the use of finansteride to inhibit 5α-reductase also partially inhibited the effects of progesterone. The involvement of allopregnanolone in myelination was further demonstrated by the finding that bicuculline inhibited the effect of allopregnanolone, providing evidence that allopregnanolone was involved in the increased expression of myelin basic proteins.

Hence, allopregnanolone has pronounced neuroprotective actions, increases myelination, and enhances neurogenesis and cell survival. Evidence suggests that allopregnanolone dysregulation may play a role in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders, as demonstrated by data that allopregnanolone is reduced in the prefrontal and temporal cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease compared to cognitively intact male control subjects and inversely correlated with the neuropathological disease stages. Thus, the normal age-related decline of allopregnanolone or its decline and that of other neurosteroids in psychiatric or neurological disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) may trigger the subsequent decrease of neurogenesis and decreased expression of growth factors (Wang et al., 2008). Alternatively, the restored brain content of allopregnanolone following treatment with a steroidogenic drugs reverses neurogenesis downregulation and improves emotional and cognitive function (Santarelli et al., 2003; David et al., 2009).

Relationship between BDNF and Allopregnanolone in Corticolimbic Neurons

Decreased levels of BDNF have been implicated in the mechanisms underlying the clinical manifestations of PTSD and depression and also in an impairment of cognitive function in neurologic and psychiatric disorders following protracted stressful events. A hyperactive HPA axis and higher levels of circulating glucocorticoids have been associated with dysfunctional emotional behavior that can be normalized by antidepressant treatment (Holsboer and Barden, 1996; Mason and Pariante, 2006). It has been well established that protracted stressful events affecting emotional behaviors also decrease the levels of neurotrophins, including BDNF. Both PTSD and depressed patients express decreased levels of BDNF in the hippocampus and plasma (Sen et al., 2008). Of note, PTSD and depression have consistently been associated with decreased hippocampal volume with no differences in total cerebral volume or functional impairment (Sheline et al., 1996, 2002; Schmahl et al., 2009; Acheson et al., 2011). Studies aimed at identifying the functional significance of hippocampal volume loss demonstrated an association between hippocampal volume decrease and memory loss (Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). Altogether, these studies suggest that depression and PTSD are associated with hippocampal atrophy. Therapy using neurosteroidogenic antidepressants resulted in an improvement of PTSD and depressive symptoms and in a significant improvement in mean hippocampal volume (Vermetten et al., 2003; Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). In several studies, these neurosteroidogenic antidepressants have been reported to upregulate serum and hippocampal BDNF levels in post-mortem brains, which correlated with improved symptoms (Chen et al., 2001; Shimizu et al., 2003; Sen et al., 2008). Similar results were reported in individuals who received electroconvulsive therapy (Altar et al., 2003). Thus, these results suggest that antidepressant-mediated BDNF upregulation may counteract hippocampal atrophy by stimulating dendritic spine arborization and morphology and neurogenesis.

Several stress models in rodents, including acute or protracted restrain stress, resulted in decreased expression levels of hippocampal BDNF (reviewed in Smith et al., 1995; Ueyama et al., 1997; Tapia-Arancibia et al., 2004). Protracted social isolation is also a powerful stressful condition that would account for several dysfunctional emotional phenotypes associated with reduced expression of BDNF. For instance, social isolation in mice increased emotionality and HPA axis levels while reducing expression of BDNF levels (Berry et al., 2011). Isolation of rats at weaning reduced immobility time in the forced swim test, decreased sucrose intake and preference, and downregulated both BDNF and activity-regulated cytoskeletal associated protein (Arc) in the hippocampus (Pisu et al., 2011). Likewise, a prolonged period of partial social isolation can modify BDNF protein concentrations selectively in the hippocampus with no changes in prefrontal cortices and striata. In this study, housing condition had no effect on basal plasma corticosterone (Scaccianoce et al., 2006).

Interestingly, plasticity in corticolimbic circuits is a prerequisite for triggering extinction of fear conditioning responses (Egan et al., 2003; Quirk and Milad, 2010). In these circuits, BDNF mediates plasticity and can be epigenetically regulated in a manner that correlates with fear extinction (Bredy et al., 2007). Accordingly, mice with a global deletion of one BDNF allele or with a forebrain-restricted deletion of both alleles show deficits in cognition, anxiety-like behavior, and elevated aggressive behavior (Rios et al., 2001). BDNF-restricted knockout mice instead exhibited elevated aggression and social dominance but did not show changes in anxiety-like behaviors (Ito et al., 2011).

Relying on these reports and on clinical and preclinical studies from our own group, we hypothesized that in PTSD and depressed patients who show a decrease of CSF allopregnanolone levels, antidepressant-induced allopregnanolone level upregulation was involved in the antidepressant mechanisms underlying the elevation of BDNF levels. Part of this hypothesis was that allopregnanolone regulates BDNF expression. Studies conducted in our laboratory in socially isolated mice have shown that a decrease of corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels is associated with decreased levels of corticolimbic BDNF mRNA expression (Nelson et al., 2010). We found that allopregnanolone levels and BDNF mRNA expression are downregulated in the same brain areas, namely the medial frontal cortex, hippocampus, and BLA and fail to change in the cerebellum and striatum (Pibiri et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2010).

To test whether these neurochemical deficits were associated with behavioral dysfunctions (exaggerated contextual fear conditioning and impaired extinction), mice were exposed to a novel environment (i.e., context, a training chamber) and were allowed to explore it for 2 min. After this time, they received an acoustic tone (i.e., conditioned stimulus, CS; 30 s, 85 dB) co-terminated with an unconditioned stimulus (US; electric footshock, 2 s, 0.5 mA). The tone plus the foot shock were repeated three times every 2 min. After the last tone + shock delivery, mice were allowed to explore the context for an additional minute prior to removal from the training chamber (total of 8 min). On re-exposure to the context 24 h later, the mice displayed a conditioned fear response, including sustained freezing behaviors. Freezing behavior, defined by the absence of any movement except for those related to respiration while the animal is in a stereotyped crouching posture (Pibiri et al., 2008), was measured for 5 min without tone or footshock presentation. Socially isolated mice also exhibited delayed and incomplete extinction of fear responses, which was assessed by exposing mice to the conditioning chamber on five consecutive days. The decrease of corticolimbic allopregnanolone levels and BDNF mRNA expression were also associated with changes in anxiety-like behavior and aggressiveness, which were assessed by using an elevated plus maze and the resident–intruder test, respectively (Pinna et al., 2003, 2006; Nin et al., 2011).

Of note, in socially isolated mice we further studied the mean of spine density and the percentage of mature spines in layer III of the frontal cortex. Spine density was lower for socially isolated mice along the entire extent of the apical and basilar dendrites. Socially isolated mice also had a lower percentage of mature spines on both the apical and basilar dendrites. For the apical dendrite, the greatest decrease in percentage of mature spines for isolated mice was in the proximal portion of the dendrite, while for the basilar dendrite, the greatest decrease in percentage of mature spines was in the mid and distal portion of the dendrite (Tueting and Pinna, 2002 and manuscript in preparation).

Allopregnanolone treatment or S-norfluoxetine at concentrations sufficient to increase the levels of allopregnanolone in corticolimbic areas normalized BDNF mRNA expression in corticolimbic areas of socially isolated mice (Martinez et al., 2011). This treatment also improved dendritic spine morphology and behavioral deficits. S-norfluoxetine and allopregnanolone treatment induced a reduction of conditioned fear and facilitated fear extinction (Pibiri et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2010). These treatments also prevented the reinstatement of fear memory following extinction, suggesting that allopregnanolone- or S-norfluoxetine-induced BDNF upregulation in corticolimbic areas strengthens extinction processing. Importantly, S-norfluoxetine and allopregnanolone actions on conditioned fear responses were mimicked by a single BDNF bilateral microinfusion into the BLA, which dose-dependently facilitated fear extinction and abolished the reinstatement of fear responses in the absence of locomotion impairment (Martinez et al., 2011). These observations support the hypothesis that by increasing allopregnanolone levels, SBSS drugs such as S-norfluoxetine may be involved in the regulation of corticolimbic BDNF expression and may induce long-term improvement in the behavioral dysfunctions that relate to PTSD.

These results originated in our laboratory are in accord with recent investigations suggesting that progesterone regulates BDNF expression. A study conducted with cerebral cortical explants has demonstrated that progesterone induces an upregulation of BDNF mRNA and protein expression (Kaur et al., 2007). Interestingly, allopregnanolone exerts complex acute actions in several corticolimbic structures following i.p. administration (Naert et al., 2007). In the hippocampus, the content of BDNF following an injection of allopregnanolone was first decreased after 30 min following the injection and significantly increased after 3 h. In the amygdala, BDNF content was increased after 15–60 min from allopregnanolone, returned normal, and increased again after 5 h. Finally, in the hypothalamus, BDNF levels were decreased (Naert et al., 2007). Collectively these studies suggest that part of the immediate or the long-term behavioral effects exerted by steroidogenic antidepressants may be explained by the effects of these drugs on allopregnanolone neosynthesis, which in turn may upregulate BDNF content and expression in corticolimbic neurons.

Conclusion

The incidence and prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorders and anxiety disorders are predicted to continue to increase, while current medications remain difficult due to the inefficacy of some antidepressants and benzodiazepines in the treatment of PTSD patients (Gelpin et al., 1996; Viola et al., 1997; Davidson, 2004).

We have observed that socially isolated mice, in addition to expressing a neurosteroidogenic deficit, which results in decreased levels of allopregnanolone, the most potent physiological positive modulator of GABAA receptor neurotransmission, also express a BDNF level downregulation in corticolimbic neurons. Treatment with allopregnanolone or with non-serotonergic doses of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine normalized both the levels of corticolimbic allopregnanolone and the mRNA expression of BDNF, which is associated with antianxiety and antiaggressive action as well as improvement of fear conditioning responses.

A new class of drugs, the SBSSs, which include molecules that share the ability to increase the brain levels of allopregnanolone, may have therapeutic potential for the treatment of PTSD and depression, which have been associated with a downregulation of brain allopregnanolone biosynthesis and BDNF expression.

Direct BDNF application to pharmacotherapy for psychiatric disorders is highly promising in the treatment of PTSD (Peters et al., 2010). However, the use of BDNF is difficult, particularly concerning the delivery of BDNF to the brain (Nagahara and Tuszynski, 2011). Thus, molecules that are able to endogenously stimulate BDNF levels, including SBSSs, may overcome the delivery challenge represented by administering BDNF directly.

Therefore, novel SBSS drugs that specifically increase corticolimbic allopregnanolone biosynthesis and stimulate BDNF expression in corticolimbic neurons appear to be highly promising as a new pharmacological class of future drugs for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH 085999 (to G. Pinna). Nin MS supported by CAPES Foundation 2191-10-5 fellowship.

References

- Acheson D. T., Gresack J. E., Risbrough V. B. (2011). Hippocampal dysfunction effects on context memory: possible etiology for posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropharmacology. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agis-Balboa R. C., Guidotti A., Whitfield H., Pinna G. (2010). Allopregnanolone biosynthesis is downregulated in the prefrontal cortex/Brodmann’s area 9 (BA9) of depressed patients. 2010 Neuroscience Meeting, Abstr. 881.15. [Google Scholar]

- Agis-Balboa R. C., Pinna G., Kadriu B., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2007). Down-regulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis in corticolimbic circuits mediates social isolation-induced behavior in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18736–18741 10.1073/pnas.0709419104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agis-Balboa R. C., Pinna G., Zhubi A., Maloku E., Veldic M., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2006). Characterization of brain neurons that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14602–14607 10.1073/pnas.0606544103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akk G., Shu H. J., Wang C., Steinbach J. H., Zorumski C. F., Covey D. F., Mennerick S. (2005). Neurosteroid access to the GABAA receptor. J. Neurosci. 25, 11605–11613 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4173-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso J., Frick L. R., Silberman D. M., Palumbo M. L., Genaro A. M., Frasch A. C. (2006). Regulation of hippocampal gene expression is conserved in two species subjected to different stressors and antidepressant treatments. Biol. Psychiatry 59, 244–251 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar C. A., Whitehead R. E., Chen R., Wörtwein G., Madsen T. M. (2003). Effects of electroconvulsive seizures and antidepressant drugs on brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein in rat brain. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 703–709 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00073-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin Z., Mason G. F., Cavus I., Krystal J. H., Rothman D. L., Epperson C. N. (2007). The interaction of neuroactive steroids and GABA in the development of neuropsychiatric disorders in women. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 21, 414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydemir O., Deveci A., Taneli F. (2005). The effect of chronic antidepressant treatment on serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in depressed patients: a preliminary study. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 29, 261–265 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström T., Andreen L., Birzniece V., Björn I., Johansson I. M., Nordenstam-Haghjo M., Nyberg S., Sundström-Poromaa I., Wahlström G., Wang M., Zhu D. (2003). The role of hormones and hormonal treatments in premenstrual syndrome. CNS Drugs 17, 325–342 10.2165/00023210-200317050-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu E. E. (1981). “Steroid hormones in the brain: several mechanisms,” in Steroid Hormone Regulation of the Brain, eds Fuxe K., Gustafson J. A., Wettenberg L. (Elmsford, NY: Pergamon; ), 3–14 [Google Scholar]

- Baulieu E. E., Robel P., Schumacher M. (2001). Neurosteroids: beginning of the story. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 46, 1–32 10.1016/S0074-7742(01)46057-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D., Lambert J. J. (2005). Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABAA receptor. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 565–575 10.1038/nrn1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry A., Bellisario V., Capoccia S., Tirassa P., Calza A., Alleva E., Cirulli F. (2011). Social deprivation stress is a triggering factor for the emergence of anxiety- and depression-like behaviours and leads to reduced brain BDNF levels in C57BL/6J mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitran D., Hilvers R. J., Kellogg C. K. (1991). Anxiolytic effects of 3 alpha-hydroxy-5 alpha[beta]- pregnan-20-one: endogenous metabolites of progesterone that are active at the GABAA receptor. Brain Res. 561, 157–161 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90761-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M., Schmidt P. J., Danaceau M., Murphy J., Nieman L., Rubinow D. R. (2000). Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 157, 924–930 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchio-Chiavetto L., Zanardini R., Bortolomasi M., Abate M., Segala M., Giacopuzzi M., Riva M. A., Marchina E., Pasqualetti P., Perez J., Gennarelli M. (2006). Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) increases serum brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in drug resistant depressed patients. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16, 620–624 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini M., Underwood M. D., Hen R., Rosoklija G. B., Dwork A. J., John Mann J., Arango V. (2009). Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cells in the human hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 2376–2389 10.1038/npp.2009.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolato M., Devoto P., Roncada P., Frau R., Flore G., Saba P., Pistritto G., Soggiu A., Pisanu S., Zappala A., Ristaldi M. S., Tattoli M., Cuomo V., Marrosu F., Barbaccia M. L. (2011). Isolation rearing induced reduction of brain 5α-reductase expression: relevance to dopaminergic impairments. Neuropharmacology 60, 1301–1308 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredy T. W., Wu H., Crego C., Zellhoefer J., Sun Y. E., Barad M. (2007). Histone modifications around individual BDNF gene promoters in prefrontal cortex are associated with extinction of conditioned fear. Learn. Mem. 14, 268–276 10.1101/lm.500907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N., Chase G. A., Anthony J. C. (2002). The uniqueness of the DSM definition of posttraumatic stress disorder: implications for research. Psychol. Med. 32, 573–576 10.1017/S0033291701004998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. J., Espinosa J., McIlhaney M. P., Pencek T. P., Kesslak J. P., Cotman C., Viel J., McManus D. C. (2001). Culture and regeneration of human neurons after brain surgery. J. Neurosci. Methods 107, 15–23 10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00342-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton R. D., Wang J. M. (2006). Preclinical analyses of the therapeutic potential of allopregnanolone to promote neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo in transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 3, 11–17 10.2174/156720506775697160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunoni A. R., Lopes M., Fregni F. (2008). A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on depression and BDNF levels: implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11, 1169–1180 10.1017/S1461145708009309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro J. E., Varea E., Márquez C., Cordero M. I., Poirier G., Sandi C. (2010). Role of the amygdala in antidepressant effects on hippocampal cell proliferation and survival and on depression-like behavior in the rat. PLoS ONE 5, e8618. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Dowlatshahi D., MacQueen G. M., Wang J. F., Young L. T. (2001). Increased hippocampal BDNF immunoreactivity in subjects treated with antidepressant medication. Biol. Psychiatry 50, 260–265 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney D. L., Uzunov D., Costa E., Guidotti A. (1995). Gas chromatographic-mass fragmentographic quantitation of 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (allopregnanolone) and its precursors in blood and brain of adrenalectomized and castrated rats. J. Neurosci. 15, 4641–4650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowansage K. K., LeDoux J. E., Monfils M. H. (2010). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a dynamic gatekeeper of neural plasticity. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 3, 12–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle J. T., Duman R. S. (2003). Finding the intracellular signaling pathways affected by mood disorder treatments. Neuron 38, 157–160 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00195-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquila P. S., Canu S., Sardella M., Spanu C., Serra G., Franconi F. (2010). Dopamine is involved in the antidepressant-like effect of allopregnanolone in the forced swimming test in female rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 21, 21–28 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833470a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David D. J., Samuels B. A., Rainer Q., Wang J. W., Marsteller D., Mendez I., Drew M., Craig D. A., Guiard B. P., Guilloux J. P., Artymyshyn R. P., Gardier A. M., Gerald C., Antonijevic I. A., Leonardo E. D., Hen R. (2009). Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron 62, 479–493 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J. R. (2004). Use of benzodiazepines in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65, 29–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Aimone J. B., Gage F. H. (2010). New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 339–350 10.1038/nrn2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deo G. S., Dandekar M. P., Upadhya M. A., Kokare D. M., Subhedar N. K. (2010). Neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors in the central nucleus of amygdala mediate the anxiolytic-like effect of allopregnanolone in mice: behavioral and immunocytochemical evidences. Brain Res. 1318, 77–86 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Désarnaud F., Do Thi A. N., Brown A. M., Lemke G., Suter U., Baulieu E. E., Schumacher M. (1998). Progesterone stimulates the activity of the promoters of peripheral myelin protein-22 and protein zero genes in Schwann cells. J. Neurochem. 71, 1765–1768 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong E., Matsumoto K., Uzunova V., Sugaya I., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2001). Brain 5α-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone synthesis in a mouse model of protracted social isolation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 2849–2854 10.1073/pnas.051628598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranovsky A., Hen R. (2006). Hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation by stress and antidepressants. Biol. Psychiatry 59, 1136–1143 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranovsky A., Picchini A. M., Moadel T., Sisti A. C., Yamada A., Kimura S., Leonardo E. D., Hen R. (2011). Experience dictates stem cell fate in the adult hippocampus. Neuron 70, 908–923 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman R. S. (2004). Depression: a case of neuronal life and death? Biol. Psychiatry 56, 140–145 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M. F., Kojima M., Callicott J. H., Goldberg T. E., Kolachana B. S., Bertolino A., Zaitsev E., Gold B., Goldman D., Dean M., Lu B., Weinberger D. R. (2003). The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell 112, 257–269 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00035-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehninger D., Wang L. P., Klempin F., Römer B., Kettenmann H., Kempermann G. (2011). Enriched environment and physical activity reduce microglia and influence the fate of NG2 cells in the amygdala of adult mice. Cell Tissue Res. 345, 69–86 10.1007/s00441-011-1200-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engin E., Treit D. (2007). The anxiolytic-like effects of allopregnanolone vary as a function of intracerebral microinfusion site: the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, or hippocampus. Behav. Pharmacol. 18, 461–470 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282de7929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye C. A., Paris J. J., Rhodes M. E. (2009). Increasing 3alpha,5alpha-THP following inhibition of neurosteroid biosynthesis in the ventral tegmental area reinstates anti-anxiety, social, and sexual behavior of naturally receptive rats. Reproduction 137, 119–128 10.1530/REP-08-0250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye C. A., Rhodes M. E. (2006). Infusions of 5alpha-pregnan-3alpha-ol-20-one (3alpha,5alpha-THP) to the ventral tegmental area, but not the substantia nigra, enhance exploratory, antianxiety, social and sexual behaviours and concomitantly increase 3alpha,5alpha-THP concentrations in the hippocampus, diencephalon and cortex of ovariectomised oestrogen primed rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 18, 960–975 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01494.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelpin E., Bonne O., Peri T., Brandes D., Shalev A. Y. (1996). Treatment of recent trauma survivors with benzodiazepines: a prospective study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 57, 390–394 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonul A. S., Akdeniz F., Taneli F., Donat O., Eker C., Vahip S. (2005). Effect of treatment on serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in depressed patients. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 255, 381–386 10.1007/s00406-005-0578-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin L. D., Mellon S. H. (1999). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13512–13517 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guennoun R., Benmessahel Y., Delespierre B., Gouézou M., Rajkowski K. M., Baulieu E. E., Schumacher M. (2001). Progesterone stimulates Krox-20 gene expression in Schwann cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 90, 75–82 10.1016/S0169-328X(01)00094-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A., Dong E., Matsumoto K., Pinna G., Rasmusson A. M., Costa E. (2001). The socially-isolated mouse: a model to study the putative role of allopregnanolone and 5α-dihydroprogesterone in psychiatric disorders. Brain Res. Rev. 37, 110–115 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00129-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F., Barden N. (1996). Antidepressants and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical regulation. Endocr. Rev. 17, 187–205 10.1210/er.17.2.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie A. M., Wilkins M. E., da Silva H. M., Smart T. G. (2006). Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature 444, 486–489 10.1038/nature05324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito W., Chehab M., Thakur S., Li J., Morozov A. (2011). BDNF-restricted knockout mice as an animal model for aggression. Genes Brain Behav. 10, 365–374 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00676.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N. S., Hirani K., Chopde C. T. (2005). Reversal of caffeine-induced anxiety by neurosteroid 3-alpha-hydroxy-5-alpha-pregnane-20-one in rats. Neuropharmacology 48, 627–638 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karege F., Bondolfi G., Gervasoni N., Schwald M., Aubry J. M., Bertschy G. (2005). Low brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in serum of depressed patients probably results from lowered platelet BDNF release unrelated to platelet reactivity. Biol. Psychiatry 57, 1068–1072 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karege F., Perret G., Bondolfi G., Schwald M., Bertschy G., Aubry J. M. (2002). Decreased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in major depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. 109, 143–148 10.1016/S0165-1781(02)00005-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karishma K. K., Herbert J. (2002). Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) stimulates neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the rat, promotes survival of newly formed neurons and prevents corticosterone-induced suppression. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 445–453 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur P., Jodhka P. K., Underwood W. A., Bowles C. A., de Fiebre N. C., de Fiebre C. M., Singh M. (2007). Progesterone increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and protects against glutamate toxicity in a mitogen-activated protein kinase- and phosphoinositide-3 kinase-dependent manner in cerebral cortical explants. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 2441–2449 10.1002/jnr.21370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller E. A., Zamparini A., Borodinsky L. N., Gravielle M. C., Fiszman M. L. (2004). Role of allopregnanolone on cerebellar granule cells neurogenesis. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 153, 13–17 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G., Gage F. H. (1998). Closer to neurogenesis in adult humans. Nat. Med. 4, 555–557 10.1038/nm0598-555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G., Kronenberg G. (2003). Depressed new neurons–adult hippocampal neurogenesis and a cellular plasticity hypothesis of major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 499–503 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00319-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita A., Furukawa K. (2008). Involvement of neurosteroids in the anxiolytic-like effects of AC-5216 in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 89, 171–178 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshimizu H., Hazama S., Hara T., Ogura A., Kojima M. (2010). Distinct signaling pathways of precursor BDNF and mature BDNF in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 473, 229–232 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. J., Belelli D., Peden D. R., Vardy A. W., Peters J. A. (2003). Neurosteroid modulation of GABAA receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 71, 67–80 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. J., Cooper M. A., Simmons R. D., Weir C. J., Belelli D. (2009). Neurosteroids: endogenous allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34, S48–S58 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang U. E., Bajbouj M., Gallinat J., Hellweg R. (2006). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor serum concentrations in depressive patients during vagus nerve stimulation and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 187, 156–159 10.1007/s00213-006-0399-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner B., Mendolia-Loffredo S., Kozorovitskiy Y., Samburg D., Gould E., Shors T. J. (2004). Learning enhances the survival of new neurons beyond the time when the hippocampus is required for memory. J. Neurosci. 24, 7477–7481 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0204-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B., Buck C. R., Dreyfus C. F., Black I. B. (1989). Expression of NGF and NGF receptor mRNAs in the developing brain: evidence for local delivery and action of NGF. Exp. Neurol. 104, 191–199 10.1016/0014-4886(89)90029-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska M. D. (1992). Neurosteroids: endogenous bimodal modulators of the GABAA receptor. Mechanism of action and physiological significance. Prog. Neurobiol. 38, 379–395 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90025-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez L. A., Pibiri F., Nelson M., Nin M. S., Pinna G. (2011). Selective brain steroidogenic stimulant (SBSS)-induced neurosteroid upregulation facilitates fear extinction and reinstatement of fear memory by a BDNF-mediated mechanism in a mouse model of PTSD. Society for Neuroscience 2011 Abstract, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Garcia E., Pallares M. (2005). The intrahippocampal administration of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone blocks the audiogenic seizures induced by nicotine. Brain Res. 1062, 144–150 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx C. E., Keefe R. S., Buchanan R. W., Hamer R. M., Kilts J. D., Bradford D. W., Strauss J. L., Naylor J. C., Payne V. M., Lieberman J. A., Savitz A. J., Leimone L. A., Dunn L., Porcu P., Morrow A. L., Shampine L. J. (2009). Proof-of concept trial with the neurosteroid pregnenolone targeting cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 1885–1903 10.1038/npp.2009.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason B. L., Pariante C. M. (2006). The effects of antidepressants on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Drug News Perspect. 19, 603–608 10.1358/dnp.2006.19.10.1068007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrisciano F., Bonaccorso S., Ricciardi A., Scaccianoce S., Panaccione I., Wang L., Ruberto A., Tatarelli R., Nicoletti F., Girardi P., Shelton R. C. (2009). Changes in BDNF serum levels in patients with depression disorder (MDD) after 6 months treatment with sertraline, escitalopram, or venlafaxine. J. Psychiatr. Res. 43, 247–254 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Nomura H., Murakami Y., Taki K., Takahata H., Watanabe H. (2003). Long-term social isolation enhances picrotoxin seizure susceptibility in mice: up-regulatory role of endogenous brain allopregnanolone in GABAergic systems. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 75, 831–835 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00169-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Puia G., Dong E., Pinna G. (2007). GABAA receptor neurotransmission dysfunction in a mouse model of social isolation-induced stress: possible insights into a nonserotonergic mechanism of action of SSRIs in mood and anxiety disorders. Stress 10, 3–12 10.1080/10253890701200997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Uzunova V., Pinna G., Taki K., Uzunov D. P., Watanabe H., Mienvielle J.-M., Guidotti A., Costa E. (1999). Permissive role of brain allopregnanolone content in the regulation of pentobarbital-induced righting reflex loss. Neuropharmacology 38, 955–963 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00018-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T., Rauskolb S., Polack M., Klose J., Kolbeck R., Korte M., Barde Y. A. (2008). Biosynthesis and processing of endogenous BDNF: CNS neurons store and secrete BDNF, not pro-BDNF. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 131–133 10.1038/nn2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S., Magarinos A. M., Reagan L. P. (2002). Structural plasticity and tianeptine: cellular and molecular targets. Eur. Psychiatry 17, 318–330 10.1016/S0924-9338(02)00650-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcangi R. C., Magnaghi V., Cavarretta I., Martini L., Piva F. (1998). Age-induced decrease of glycoprotein Po and myelin basic protein gene expression in the rat sciatic nerve. Repair by steroid derivatives. Neuroscience 85, 569–578 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00628-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcangi R. C., Magnaghi V., Cavarretta I., Zucchi I., Bovolin P., D’Urso D., Martini L. (1999). Progesterone derivatives are able to influence peripheral myelin protein 22 and P0 gene expression: possible mechanisms of action. J. Neurosci. Res. 56, 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon S. H. (2007). Neurosteroid regulation of central nervous system development. Pharmacol. Ther. 116, 107–124 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteggia L. M., Barrot M., Powell C. M., Berton O., Galanis V., Gemelli T., Meuth S., Nagy A., Greene R. W., Nestler E. J. (2004). Essential role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult hippocampal function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10827–10832 10.1073/pnas.0402141101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowla S. J., Pareek S., Farhadi H. F., Petrecca K., Fawcett J. P., Seidah N. G., Morris S. J., Sossin W. S., Murphy R. A. (1999). Differential sorting of nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 19, 2069–2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naert G., Maurice T., Tapia-Arancibia L., Givalois L. (2007). Neuroactive steroids modulate HPA axis activity and cerebral brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein levels in adult male rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32, 1062–1078 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara A. H., Tuszynski M. H. (2011). Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 209–219 10.1038/nrd3366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi R. E., Petraglia F., Luisi S., Polatti F., Farina C., Genazzani A. R. (2001). Serum allopregnanolone in women with postpartum “blues”. Obstet. Gynecol. 97, 77–80 10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01112-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M., Pibiri F., Pinna G. (2010). Relationship between allopregnanolone (Allo) and reduced brain BDNF and reelin expression in a mouse model of posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD). Soc. Neurosci. 2010 Abstr 666.22. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M., Pinna G. (2011). S-norfluoxetine infused into the basolateral amygdala increases allopregnanolone levels and reduces aggression in socially isolated mice. Neuropharmacology 60, 1154–1159 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M., Morinobu S., Duman R. S. (1995). Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J. Neurosci. 15, 7539–7547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nin M. S., Salles F. B., Azeredo L. A., Frazon A. P., Gomez R., Barros H. M. (2008). Antidepressant effect and changes of GABAA receptor gamma2 subunit mRNA after hippocampal administration of allopregnanolone in rats. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 22, 477–485 10.1177/0269881107081525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nin M. S., >Martinez L. A., Thomas R., Nelson M., Pinna G. (2011). Allopregnanolone and S-norfluoxetine decrease anxiety-like behavior in a mouse model of anxiety/depression. Trab. Inst. Cajal 83, 215–216 [Google Scholar]

- Notterpek L., Snipes G. J., Shooter E. M. (1999). Temporal expression pattern of peripheral myelin protein 22 during in vivo and in vitro myelination. Glia 25, 358–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstein T. (2010). Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: out of the appendix. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 13, 21–23 10.1007/s00737-009-0111-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J., Dieppa-Perea L. M., Melendez L. M., Quirk G. J. (2010). Induction of fear extinction with hippocampal-infralimbic BDNF. Science 328, 1288–1290 10.1126/science.328.5980.824-b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pibiri F., Nelson M., Guidotti A., Costa E., Pinna G. (2008). Decreased allopregnanolone content during social isolation enhances contextual fear: a model relevant for posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5567–5572 10.1073/pnas.0807172105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinni A., Marazziti D., Catena M., Domenici L., Del Debbio A., Bianchi C., Mannari C., Martini C., Da Pozzo E., Schiavi E., Mariotti A., Roncaglia I., Palla A., Consoli G., Giovannini L., Massimetti G., Dell’Osso L. (2008). Plasma and serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depressed patients during 1 year of antidepressant treatments. J. Affect. Disord. 105, 279–283 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G. (2010). In a mouse model relevant for post-traumatic stress disorder, selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSS) improve behavioral deficits by normalizing allopregnanolone biosynthesis. Behav. Pharmacol. 21, 438–450 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833d8ba0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G., Agis-Balboa R., Pibiri F., Nelson M., Guidotti A., Costa E. (2008). Neurosteroid biosynthesis regulates sexually dimorphic fear and aggressive behavior in mice. Neurochem. Res. 33, 1990–2007 10.1007/s11064-008-9718-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2004). Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically facilitate pentobarbital sedation by increasing neurosteroids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6222–6225 10.1073/pnas.0401479101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2006). Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 186, 362–372 10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2009). SSRIs act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) at low doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 9, 24–30 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G., Dong E., Matsumoto K., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2003). In socially isolated mice, the reversal of brain allopregnanolone down-regulation mediates the anti-aggressive action of fluoxetine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2035–2040 10.1073/pnas.0337642100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna G., Uzunova V., Matsumoto K., Puia G., Mienville J.-M., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2000). Brain allopregnanolone regulates the potency of the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol. Neuropharmacology 39, 440–448 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00149-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock S. B., Lazic S. E., Wong H. T., Wong I. H., Herbert J. (2009). Synergistic effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and fluoxetine on proliferation of progenitor cells in the dentate gyrus of the adult male rat. Neuroscience 158, 1644–1651 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisu M. G., Dore R., Mostallino M. C., Loi M., Pibiri F., Mameli R., Cadeddu R., Secci P. P., Serra M. (2011). Down-regulation of hippocampal BDNF and Arc associated with improvement in aversive spatial memory performance in socially isolated rats. Behav. Brain Res. 222, 73–80 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G., Mienville J.-M., Matsumoto K., Takahata H., Watanabe H., Costa E., Guidotti A. (2003). On the putative physiological role of allopregnanolone on GABAA receptor function. Neuropharmacology 44, 49–55 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00341-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G., Santi M. R., Vicini S., Pritchett D. B., Purdy R. H., Paul S. M., Seeburg P. H., Costa E. (1990). Neurosteroids act on recombinant human GABAA receptors. Neuron 4, 759–765 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90202-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G., Vicini S., Seeburg P. H., Costa E. (1991). Influence of recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid – a receptor subunit composition on the action of allosteric modulators of gammaaminobutyricacid-gated Cl-currents. Mol. Pharmacol. 39, 691–696 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk G. J., Milad M. R. (2010). Neuroscience: editing out fear. Nature 463, 36–37 10.1038/463036a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapkin A. J., Morgan M., Goldman L., Brann D. W., Simone D., Mahesh V. B. (1997). Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. 90, 709–714 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00417-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson A. M., Pinna G., Paliwal P., Weisman D., Gottschalk C., Charney D., Krystal J., Guidotti A. (2006). Decreased cerebrospinal fluid allopregnanolone levels in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 60, 704–713 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb S., Zagrebelsky M., Dreznjak A., Deogracias R., Matsumoto T., Wiese S., Erne B., Sendtner M., Schaeren-Wiemers N., Korte M., Barde Y. A. (2010). Global deprivation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the CNS reveals an area-specific requirement for dendritic growth. J. Neurosci. 30, 1739–1749 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5100-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios M., Fan G., Fekete C., Kelly J., Bates B., Kuehn R., Lechan R. M., Jaenisch R. (2001). Conditional deletion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the postnatal brain leads to obesity and hyperactivity. Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 1748–1757 10.1210/me.15.10.1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers R. J., Johnson N. J. (1998). Behaviorally selective effects of neuroactive steroids on plus-maze anxiety in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 59, 221–232 10.1016/S0091-3057(97)00339-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo E., Ströhle A., Spalletta G., di Michele F., Hermann B., Holsboer F., Pasini A., Rupprecht R. (1998). Effects of antidepressant treatment on neuroactive steroids in major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 910–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht R., Papadopoulos V., Rammes G., Baghai T. C., Fan J., Akula N., Groyer G., Adams D., Schumacher M. (2010). Translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO) as a therapeutic target for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 971–988 10.1038/nrd3295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht R., Rammes G., Eser D., Baghai T. C., Schüle C., Nothdurfter C., Troxler T., Gentsch C., Kalkman H. O., Chaperon F., Uzunov V., McAllister K. H., Bertaina-Anglade V., La Rochelle C. D., Tuerck D., Floesser A., Kiese B., Schumacher M., Landgraf R., Holsboer F., Kucher K. (2009). Translocator protein (18 kD) as target for anxiolytics without benzodiazepine-like side effects. Science 325, 490–493 10.1126/science.1175055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo-Neustadt A. A., Alejandre H., Garcia C., Ivy A. S., Chen M. J. (2004). Hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression following treatment with reboxetine, citalopram, and physical exercise. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 2189–2199 10.1038/sj.npp.1300514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarelli L., Saxe M., Gross C., Surget A., Battaglia F., Dulawa S., Weisstaub N., Lee J., Duman R., Arancio O., Belzung C., Hen R. (2003). Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 301, 805–809 10.1126/science.1083328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]