Abstract

The function of tumor suppressor VHL is compromised in the vast majority of clear cell renal cell carcinoma, and its mutations or loss of expression was causal for this disease. pVHL was found to be a substrate recognition subunit of an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and most of the tumor-derived mutations disrupt this function. pVHL was found to bind to the alpha subunits of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) and promote their ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Proline hydroxylation on key sites of HIFα provides the binding signal for pVHL E3 ligase complex. Beside HIFα, several other VHL targets have been identified, including activated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), RNA polymerase II subunits RPB1 and hsRPB7, atypical protein kinase C (PKC), Sprouty2, β-adrenergic receptor II, and Myb-binding protein p160. HIFα is the most well studied substrate and has been proven to be critical for pVHL’s tumor suppressor function, but the activated EGFR and PKC and other pVHL substrates might also be important for tumor growth and drug response. Their regulations by pVHL and their relevance to signaling and cancer are discussed.

Keywords: ubiquitin, VHL, HIF, ccRCC, EGFR, proline hydroxylation

von Hippel–Lindau (VHL), the Regulation of the Alpha Subunits of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor, and Oxygen Sensing

Loss of function of the tumor suppressor gene VHL is causal in the pathogenesis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). The vast majority (70–80%) of sporadic RCCs are pathologically characterized as ccRCC. Among them, approximately 70% harbor biallelic inactivation of VHL through mutation, deletion, or hypermethylation of promoter (Kaelin, 2002; Linehan and Zbar, 2004). Inherited germline mutations in VHL predispose these patients to bilateral kidney cancer earlier than the sporadic kidney cancer patients, since the loss of the remaining wild type allele occurs more readily than the loss of two alleles. The protein product of the VHL tumor suppressor gene, pVHL, is found to be the substrate recognition unit of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that contains Cullin 2 (Cul2), Elongin B and C, and Rbx1 (Kamura et al., 1999a,b). Interestingly, tumor-derived point mutations were found to cluster around substrate recognizing (β domain) or the Elongin C-binding (α domain) sites (Stebbins et al., 1999), stressing the importance of ubiquitin ligase activity to pVHL’s tumor suppressor function. This complex targets the α subunits of the heterodimeric transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) for ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation (Ohh et al., 2000). In addition to being a part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, pVHL also regulates other HIF-independent biological processes such as inhibition of NF-κB activity (Yang et al., 2007), maintenance of chromosome stability (Thoma et al., 2009), and promoting cilia production (Schraml et al., 2009), which will not be reviewed in this article.

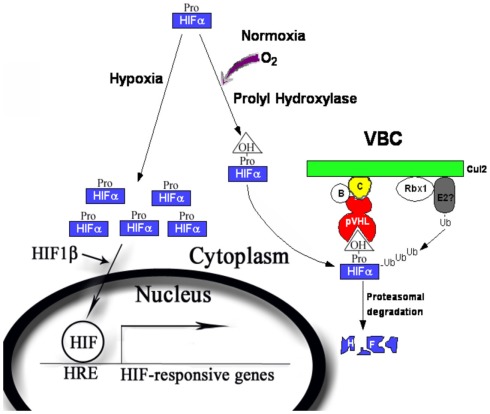

The best-characterized substrates for pVHL-containing ubiquitin ligase are the alpha subunits of the HIF transcription factor. HIF contains two subunits: the oxygen-sensitive alpha subunits (HIF1α, HIF2α, and HIF3α, for the simplicity they will be collectively called HIFα) and the constitutively expressed HIF1β subunit [also called the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator (ARNT); Semenza, 2007]. pVHL recognizes the HIFα only after they are hydroxylated on either of two critical prolyl residues by members of the EglN family (also called PHDs or HPHs; Epstein et al., 2001; Ivan et al., 2001, 2002; Jaakkola et al., 2001). These enzymes require molecular oxygen, Fe(II) and 2-oxoglutarate for activity. Under normal oxygen tension (normoxia), the critical proline residues on HIFα subunits are hydoxylated (P402 and 564 on HIF1α), recognized by pVHL, poly-ubiquitinated, and destroyed by the proteasome. When the oxygen is deprived (hypoxia) by physiological or pathological conditions, the HIFα subunits will be produced but cannot be prolyl hydroxylated. They escape the recognition by pVHL, accumulate, and hetero-dimerize with HIF1β. The heterodimer enters nucleus, recruit transcriptional coactivator complexes (Arany et al., 1996; Ema et al., 1999), and regulate the expression of (inducing or suppressing) hundreds of target genes by binding to the hypoxia-response element (HRE; Semenza, 2003; Figure 1). Activation of HIF leads to physiological adaptations to the deprivation of oxygen: a metabolic shift to anaerobic glycolysis, increased secretion of pro-angiogenesis factors that leads to growth of blood vessels and increased blood supply, remodeling of the extracellular matrix, and resistance to apoptosis and increased mobility. In VHL-defective ccRCC tumors, enhanced angiogenesis and constitutive activation of the HIF pathway are prominent features even when the oxygen supply is not limited. In the xenograft models of ccRCC, constitutive HIF activation was both sufficient (Kondo et al., 2002) and necessary for tumor growth (Kondo et al., 2003; Zimmer et al., 2004). In the clinic trials, drugs that block the activities of the receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a critical HIF target gene, produced clear and positive, albeit often transient, clinical outcomes in kidney cancer patients (Rini, 2005).

Figure 1.

The regulation of the HIFα by pVHL-containing E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. During normoxia, HIFα is produced and prolyl hydroxylated by PHD1–3. The hydroxyproline provides a binding signal for pVHL, which leads to efficient ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of HIFα protein. During hypoxia, HIFα is not prolyl hydroxylated and escapes pVHL recognition. HIFα accumulates and forms complex with HIF1β, goes into nucleus and turns on a transcriptional program to cope with the short-term and long-term effects of oxygen deprivation.

Interestingly, although HIF2α is a potent oncogene, the activations of HIF targets are not necessarily all tumor-promoting events. HIF-dependent activation of REDD1 suppressed mTORC1 (Kucejova et al., 2011), and HIF-dependent activation of JARID1C decreased the overall level of the trimethylated histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4Me3; Niu et al., 2012). Both were tumor-suppressive events, and kidney tumors found clever ways to inactivate them (Dalgliesh et al., 2010; Kucejova et al., 2011). Further careful analysis of how HIF targets contribute to kidney tumor growth and maintenance might yield new ways to treat kidney cancer.

Activated Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

It is known that HIF can enhance epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activity to promote tumor growth (de Paulsen et al., 2001; Franovic et al., 2007). In VHL-defective ccRCC cells, the expression of transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), an agonist to EGFR, is induced by HIF2α. This stimulates cell proliferation through an autocrine loop (de Paulsen et al., 2001). At the same time, constitutively active HIF2α also increases the translational efficiency of EGFR mRNA (Franovic et al., 2007). Increased EGFR expression and elevated TGF-α work together to promote autonomous growth (cellular growth in the absence of stimulating growth factors), which is a hallmark of cancer. Stable suppression of EGFR by shRNAs prevents serum-free growth of VHL-defective ccRCC cells in vitro, and retards the tumor growth of these cells for extended periods in vivo without affecting HIF2α functions (Smith et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2008). This suggests that EGFR is critical for the tumor growth of VHL-defective ccRCC cells and could be a good therapeutic target in kidney cancer.

Epidermal growth factor receptor is implicated in many human cancers, as activating mutations of EGFR have been identified in human glioblastoma, non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC), and colon cancer. Upon ligand binding, EGFR and its family members homo- or hetero-dimerize, trans-phosphorylate the c-terminal tyrosine residues. These phosphorylated residues recruit signaling molecules, which activate downstream effectors and elicit biological responses (Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001). Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PDK1/Akt1 are two major downstream pathways of activated EGFR. Since they promote both cellular proliferation and resistance to apoptosis (Jorissen et al., 2003), failure to turn off the activated EGFR can drive tumorigenesis.

Endocytosis and lysosome-mediated degradation is reported to be the major mechanism to down-regulate the activated EGFR. By binding to EGFR either directly through phosphorylated Y1045 (Levkowitz et al., 1999) or through its association with another EGFR-interacting protein Grb2 (Waterman et al., 2002), the ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl promotes its ubiquitination (Levkowitz et al., 1998). c-Cbl promotes mono-ubiquitylation on multiple lysine residues of EGFR, which is sufficient for EGFR endocytosis and degradation (Haglund et al., 2003a,b; Mosesson et al., 2003), However, mass-spectrometric and western blot analyses have suggested that a fraction of activated EGFR is poly-ubiquitinated (Huang et al., 2006; Umebayashi et al., 2008). Thus it is possible that other E3 ubiquitin ligases add poly-ubiquitin to the activated EGFR to promote its turnover.

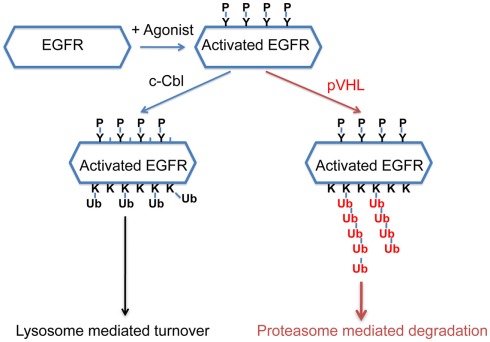

Recently it was reported that pVHL was essential for the clearance of activated EGFR (Wang et al., 2009) and the proposed mechanism was that constitutively active HIF suppressed the lysosomal-mediated degradation of the activated EGFR. Specifically, Wang et al. suggested that HIF reduced the expression of Rabaptin-5. As Rabaptin-5 was critical for Rab5-mediated endosome fusion, reduced expression of Rabaptin-5 led to delayed EGFR sorting to the late endosome and lysosome, and this led to longer half-lives of the activated EGFR. This explanation predicted that delayed turnover of activated EGFR in VHL-defective ccRCC cells was due to high levels of HIF α subunits. However, Zhou and Yang (2011) found that the endogenous HIF was not the only or major cause of delayed EGFR turnover in VHL-defective ccRCC cells. Furthermore, they found that pVHL-mediated down-regulation of the activated EGFR was mostly mediated by proteasome instead of lysosome. In addition, loss of both c-Cbl and VHL caused the activated EGFR to become completely stable during the experiment, suggesting that these ubiquitin ligases collaborated to down-regulate activated EGFR. Finally it was reported that pVHL promoted the poly-ubiquitination of the activated EGFR, and this persisted in the absence of c-Cbl. Thus in ccRCC cells, pVHL promotes the poly-ubiquitination of the activated EGFR and subsequent proteasomal degradation that is independent of c-Cbl (Figure 2). Further study is needed to determine the relative contributions of the HIF-dependent and HIF-independent mechanisms that pVHL uses to suppress activated EGFR. Nevertheless, in VHL-defective ccRCC cells, the prolonged signaling of the activated EGFR, together with elevated TGF-α and EGFR protein level, likely contributes to tumor growth. As the activated EGFR that is phosphorylated at some sites displayed VHL-dependent degradation (unpublished data), it is likely that pVHL-dependent polyubiquitination of activated EGFR is not a phenomenon that is unique to kidney cancer cells.

Figure 2.

A model of how pVHL and c-Cbl promote the turnover of the activated EGFR. After EGFR is activated by its agonist, it becomes phosphorylated at multiple sites. c-Cbl promotes multi-mono-ubiquitylation on the activated EGFR which leads to lysosome-mediated turnover, while pVHL promotes polyubiquitination on the activated EGFR which leads to proteasomal degradation.

RNA Polymerase II Subunits

Large subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB1) is responsible for the initiation and elongation of mRNA and its activity is regulated through its c-terminal phosphorylation (Kuznetsova et al., 2003; Table 1). Through bioinformatic analysis, Kuznetsova et al. (2003) found that a fragment of RPB1 share some sequence similarity with oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD) of HIF1α. In addition, RPB1 also contained an analogous LXXLAP sequence that was found in HIF1α protein that was the site of prolyl hydroxylation that mediated recognition by pVHL. In response to DNA damage agents or UV radiation, RPB1 underwent hyperphosphorylation and then proline hydroxylation. This led to recognition by pVHL-associated E3 ligase complex and its ubiquitination in PC12 cells. By testing the in vitro binding between RPB1 peptide and radio-labeled pVHL, they showed that hydroxylated RPB1 Proline 1465 was the major site that mediated interaction with pVHL. However, it remained to be determined whether hyperphosphorylation on RPB1 led to its proline hydroxylation. They also showed that the amount of hyperphosphorylated, but not hypophosphorylated RPB1 correlates inversely with pVHL levels in PC12 cells. These data suggests that pVHL binds to RPB1 through hydroxylated proline, promotes the ubiquitination of RPB1, and reduces hyperphosphorylated RPB1 levels in response to UV or DNA damage agents in PC12 cells.

Table 1.

A brief description of the pVHL substrates and the types of cancer they are involved in.

| Gene name | Biological functions | Types of cancer involved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIFα (HIF1, 2, and 3α) | Mediate transcriptional adaptation to oxygen deprivation by enhancing metabolic change, migration, and angiogenesis | All types of cancer | Semenza (2010) |

| EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) | Activate Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PDK1/Akt1 pathways; promote cell proliferation; and resistance to apoptosis | All types of cancer | Jorissen et al. (2003), Yarden and Sliwkowski (2001) |

| RPB1 (large subunit of RNA polymerase II) | The largest subunit of RNA polymerase II, the polymerase responsible for synthesizing messenger RNA in eukaryotes | Kidney cancer | Yi et al. (2010) |

| RPB7 (RNA polymerase II seventh subunit) | The seventh largest subunit of RNA polymerase II that reportedly increases VEGF expression | Kidney cancer | Na et al. (2003) |

| aPKC (atypical protein kinase C) | Activates MAPK and upregulate VEGF expression (PKCδ); phosphorylates MUC1 and potentiates β-catenin signaling (PKCδ); increases cancer cell migration (PKCδ); acts as endogenous inhibitors of tight junction formation (PKCζII) | Breast cancer Colon cancer Kidney cancer Endometrial cancer |

Pal et al. (1997), Ren et al. (2002), Razorenova et al. (2011), Reno et al. (2008), Parkinson et al. (2004) |

| SPRY2 (sprouty2) | Antagonizes the activated receptor tyrosine kinases and downregulates angiogenesis | Breast cancer Hepatocellular cancer prostate cancer Lung cancer Colon cancer | Lee et al. (2001), Lo et al. (2004), Fong et al. (2006), McKie et al. (2005), Sutterluty et al. (2007), Feng et al. (2011) |

| β2AR (β-adrenergic receptor II) | Mediate the catecholamine-induced activation of adenylate cyclase through the action of G proteins. involved in cardiovascular functions and apoptosis | Currently not known | Rockman et al. (2002) |

| MYBBP1A (Myb-binding protein p160) | May activate or repress transcription through interactions with DNA-binding proteins | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Diaz et al. (2007), Tavner et al. (1998), Acuna Sanhueza et al. (2012) |

Surprisingly, when pVHL was re-expressed in two different VHL-deficient kidney cancer cell lines, pVHL increased the level of RPB1 instead of decreasing it as expected (Mikhaylova et al., 2008). Furthermore, overexpression of wild type RPB1, not the P1465A mutant that cannot be hydroxylated, promoted tumor growth in kidney cancer cells expressing wild type VHL. Since the P1465A mutant RPB1 escapes VHL regulation, this is against the hypothesis that loss of VHL regulation on RPB1 is a tumor-promoting event. However, subsequent studies did reveal that RPB1 hydroxylation was significantly higher in kidney tumors compared to normal control. Consistent with the finding that PHD1 (EglN2, one of prolyl hydroxylases that modify HIFα) was the primary hydroxylase that modifies RPB1, levels of RPB1 hydroxylation correlated with levels of PHD1 in kidney cancer (Yi et al., 2010). Thus the contribution of RPB1 hydroxylation and pVHL-dependent ubiquitination to kidney cancer remains unclear and awaits further investigation.

In addition to RPB1, Na et al. discovered a novel pVHL-interacting protein, human RNA polymerase II seventh subunit (hsRPB7) by performing yeast two-hybrid screening from a kidney cDNA library. hsRBP7 bound to the 54–113 amino acid regions of pVHL, a part of VHL β-domain responsible for substrate recognition (Na et al., 2003). Interestingly, two representative VHL β-domain mutants (P86H and Y98H) showed decreased binding to hsRPB7 compared to wild type. hsRBP7 underwent VHL-dependent ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation. As a functional readout, hsRPB7 can positively regulate VEGF expression, an effect that was ameliorated by overexpressing VHL in kidney cancer cells. However, in this paper, it was not clear whether hydroxylation would play a role in hsRBP7’s degradation by pVHL E3 ligase complex. It will also be critical to identify the molecular mechanism by which hsRPB7 regulates the expression of specific genes such as VEGF.

Protein Kinase C

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a superfamily of phospholipid-activated serine/threonine kinase. Activation of canonical PKC family members by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-l3-acetate (TPA) can lead to various cellular responses, such as change of cell morphology and increased cell proliferation (Hata et al., 1993; Table 1). Various PKC family members were reported to bind to VHL, and this led to their ubiquitination and degradation. Although PKCδ was found to interact with the β domain of pVHL, its overall protein level was not affected by pVHL status (Iturrioz et al., 2006). Instead it was PKCζII that was reported to be a pVHL substrate, and its c-terminus was important for VHL-dependent proteasomal degradation (Iturrioz and Parker, 2007). While wild type pVHL could promote the degradation of PKCζII efficiently, some tumor-derived VHL mutants (such as Y98H, C162W, and R167W) failed to do so. However, it remained unclear whether PKCζII was a direct substrate for pVHL complex, and whether proline hydroxylation played a role in the turnover of PKCζII.

Protein kinase Cλ/4RA contains point mutations that render it partially and constitutively active (Akimoto et al., 1996). The active form of PKCλ bound to pVHL tighter than its wild type counterpart, and this led to its preferential ubiquitination by VHL E3 ligase complex (Okuda et al., 2001).

Atypical PKCλ interacted with ASIP/PAR-3 and PAR-6 and was important for the maintenance of the tight junctions and the cell polarity in epithelial cells (Suzuki et al., 2001). In another epithelial cell line HC11 PKCζII was critical to maintain the cells in a non-differentiated state characterized by the absence of tight junctions and cell overgrowth (Parkinson et al., 2004). Since pVHL was reported to bind and degrade several PKC family members, it was reasonable to hypothesize that pVHL can affect actin and cytoskeletal organization, tight junction formation and cell polarity, which were often found dysregulated in cancer cells. Further study is needed to investigate the functional role of the VHL–PKCs axis in kidney cancer.

Sprouty2

Sprouty2 (SPRY2) is one of four mammalian sprouty family members (SPRY1–4; Hacohen et al., 1998). Previous research showed that SPRY family members negatively regulated the activities of receptor tyrosine kinase and reduced angiogenesis (Lee et al., 2001; Table 1). Anderson et al. (2011) reported that hypoxia increased SPRY2 protein levels in various cancer cells, and it did so mainly through increased SPRY2 protein stability. While knockdown of PHD1 or PHD3 increased SPRY2 protein levels, overexpression of all three PHD isoforms (PHD1, 2, and 3) decreased its protein levels. By mass spectrometry, three potential prolyl hydroxylation sites were identified (P18, 144, and 160). Mutating these three Proline residues to Alanine residues significantly decreased the binding between SPRY2 and pVHL and produced more stable SPRY2 protein. Functionally, since SPRY2 was reported to have anti-migratory and anti-proliferative effect on cancer cell growth through inhibiting ERK1/2 kinase pathway (Impagnatiello et al., 2001; Yigzaw et al., 2001), suppressing either PHD1 or pVHL blunted the effect of FGF-induced ERK kinase pathway due to increased SPRY2 protein level. In a subset of hepatocellular carcinoma, pVHL protein levels were upregulated, and this led to decrease of SPRY2 protein that contributed to cancer progression (Lin et al., 2008). However, about 70% renal cell carcinomas have defects in pVHL. If the SPRY2 protein levels are upregulated in these tumors as expected, it will be intriguing to find out how this would impact tumorigenesis.

β2-Adrenergic Receptor

β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) is one of the G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Besides generating second messengers, β2AR plays an important role in control of cardiovascular functions and apoptosis (Rockman et al., 2002; Table 1). Xie et al. (2009) reported that hypoxia can stabilize β2AR protein by inhibiting its ubiquitination. Further findings demonstrated that pVHL E3 ligase complex associated with β2AR protein in vivo, contributing to its ubiquitination and degradation. Mechanistically, prolyl hydroxylase PHD3 interacted with β2AR and mediated the hydroxylation of the β2AR at proline residues 382 and 395, which primed β2AR recognition by pVHL E3 ligase complex. β2AR accounts for 25–30% of total β-type adrenergic receptor in the human heart and is the predominant form of the adrenergic receptor that exists in some of smooth muscles (Johnson, 1998; Rockman et al., 2002). Interestingly, the β2AR protein is highly expressed in heart in vivo, where PHD3 is also abundantly expressed (Xie et al., 2009). This poses an apparent paradox, as PHD3 is the major enzyme that modifies β2AR for its degradation. It might be possible that the PHD3-dependent destruction of β2AR is a regulated event and only happens with external stimuli. Although it is unclear now, the PHD3–β2AR–pVHL signaling axis might be operating in kidney cancer and merits more investigation.

Myb-Binding Protein p160 (MYBBP1A)

Using an ICAT (isotope-coded affinity tag) quantitative proteomics technology, Lai et al. identified MYBBP1A as a novel VHL substrate. MYBBP1A is a transcriptional regulator that can activate or suppress gene transcription through interacting with DNA-binding proteins (Tavner et al., 1998; Diaz et al., 2007; Table 1). MYBBP1A was degraded by VHL in a prolyl hydroxylation dependent manner. Further research showed that MYBBP1A proline 693 site as the potential hydroxylation site that might trigger the interaction with VHL and subsequent degradation (Lai et al., 2011). It remains largely unknown how MYBBP1A might contribute to kidney cancer.

Summary

Proline hydroxylation on HIFα proteins led to their recognition by pVHL, followed by very efficient ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Without a functional VHL, HIF pathway is strongly and constitutively active. So far this has been proved to be the most significant and clinically useful tumor suppressor function of pVHL. However, although proline hydroxylation on RPB1, SPRY2, and β2AR also led to pVHL-dependent ubiquitination, this did not automatically cause protein degradation as the ubiquitin chain linkages on them might be different. It is also unclear whether SPRY2 and β2AR are more abundant in VHL-defective renal cancer cells and whether they contribute to tumor growth or maintenance at all.

Interestingly, it is the active forms of EGFR and atypical PKC that are ubiquitinated by pVHL and targeted for degradation. As these kinases have pro-proliferating and anti-survival activities, it is possible that their degradation is also important to pVHL’s tumor suppressor function. It remains to be tested whether protein phosphorylations, in addition to proline hydroxylation, also constitute a recognition signal for pVHL.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Acuna Sanhueza G., Faller L., George B., Koffler J., Misetic V., Flechtenmacher C., Dyckhoff G., Plinkert P., Angel P., Simon C., Hess J. (2012). Opposing function of MYBBP1A in proliferation and migration of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer 12, 72. 10.1186/1471-2407-12-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto K., Takahashi R., Moriya S., Nishioka N., Takayanagi J., Kimura K., Fukui Y., Osada S., Mizuno K., Hirai S., Kazlauskas A., Ohno S. (1996). EGF or PDGF receptors activate atypical PKC lambda through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. EMBO J. 15, 788–798 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K., Nordquist K. A., Gao X., Hicks K. C., Zhai B., Gygi S. P., Patel T. B. (2011). Regulation of cellular levels of sprouty2 protein by prolyl hydroxylase domain and von Hippel-Lindau proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42027–42036 10.1074/jbc.M111.303222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany Z., Huang L. E., Eckner R., Bhattacharya S., Jiang C., Goldberg M. A., Bunn H. F., Livingston D. M. (1996). An essential role for p300/CBP in the cellular response to hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12969–12973 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgliesh G. L., Furge K., Greenman C., Chen L., Bignell G., Butler A., Davies H., Edkins S., Hardy C., Latimer C., Teague J., Andrews J., Barthorpe S., Beare D., Buck G., Campbell P. J., Forbes S., Jia M., Jones D., Knott H., Kok C. Y., Lau K. W., Leroy C., Lin M. L., McBride D. J., Maddison M., Maguire S., McLay K., Menzies A., Mironenko T., Mulderrig L., Mudie L., O’Meara S., Pleasance E., Rajasingham A., Shepherd R., Smith R., Stebbings L., Stephens P., Tang G., Tarpey P. S., Turrell K., Dykema K. J., Khoo S. K., Petillo D., Wondergem B., Anema J., Kahnoski R. J., Teh B. T., Stratton M. R., Futreal P. A. (2010). Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature 463, 360–363 10.1038/nature08672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paulsen N., Brychzy A., Fournier M. C., Klausner R. D., Gnarra J. R., Pause A., Lee S. (2001). Role of transforming growth factor-alpha in von Hippel–Lindau (VHL)(-/-) clear cell renal carcinoma cell proliferation: a possible mechanism coupling VHL tumor suppressor inactivation and tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 1387–1392 10.1073/pnas.031587498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz V. M., Mori S., Longobardi E., Menendez G., Ferrai C., Keough R. A., Bachi A., Blasi F. (2007). p160 Myb-binding protein interacts with Prep1 and inhibits its transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 7981–7990 10.1128/MCB.01290-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M., Hirota K., Mimura J., Abe H., Yodoi J., Sogawa K., Poellinger L., Fujii-Kuriyama Y. (1999). Molecular mechanisms of transcription activation by HLF and HIF1alpha in response to hypoxia: their stabilization and redox signal-induced interaction with CBP/p300. EMBO J. 18, 1905–1914 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A. C., Gleadle J. M., McNeill L. A., Hewitson K. S., O’Rourke J., Mole D. R., Mukherji M., Metzen E., Wilson M. I., Dhanda A., Tian Y. M., Masson N., Hamilton D. L., Jaakkola P., Barstead R., Hodgkin J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Schofield C. J., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001). C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107, 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. H., Wu C. L., Tsao C. J., Chang J. G., Lu P. J., Yeh K. T., Uen Y. H., Lee J. C., Shiau A. L. (2011). Deregulated expression of sprouty2 and microRNA-21 in human colon cancer: correlation with the clinical stage of the disease. Cancer Biol. Ther. 11, 111–121 10.4161/cbt.11.1.13965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong C. W., Chua M. S., McKie A. B., Ling S. H., Mason V., Li R., Yusoff P., Lo T. L., Leung H. Y., So S. K., Guy G. R. (2006). Sprouty 2, an inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, is down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 66, 2048–2058 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franovic A., Gunaratnam L., Smith K., Robert I., Patten D., Lee S. (2007). Translational up-regulation of the EGFR by tumor hypoxia provides a nonmutational explanation for its overexpression in human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13092–13097 10.1073/pnas.0702387104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacohen N., Kramer S., Sutherland D., Hiromi Y., Krasnow M. A. (1998). sprouty encodes a novel antagonist of FGF signaling that patterns apical branching of the Drosophila airways. Cell 92, 253–263 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80919-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K., Di Fiore P. P., Dikic I. (2003a). Distinct monoubiquitin signals in receptor endocytosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 598–603 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haglund K., Sigismund S., Polo S., Szymkiewicz I., Di Fiore P. P., Dikic I. (2003b). Multiple monoubiquitination of RTKs is sufficient for their endocytosis and degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 461–466 10.1038/ncb983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata A., Akita Y., Suzuki K., Ohno S. (1993). Functional divergence of protein kinase C (PKC) family members. PKC gamma differs from PKC alpha and -beta II and nPKC epsilon in its competence to mediate-12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol 13-acetate (TPA)-responsive transcriptional activation through a TPA-response element. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9122–9129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Kirkpatrick D., Jiang X., Gygi S., Sorkin A. (2006). Differential regulation of EGF receptor internalization and degradation by multiubiquitination within the kinase domain. Mol. Cell 21, 737–748 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impagnatiello M. A., Weitzer S., Gannon G., Compagni A., Cotten M., Christofori G. (2001). Mammalian sprouty-1 and -2 are membrane-anchored phosphoprotein inhibitors of growth factor signaling in endothelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 152, 1087–1098 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturrioz X., Durgan J., Calleja V., Larijani B., Okuda H., Whelan R., Parker P. J. (2006). The von Hippel-Lindau tumour-suppressor protein interaction with protein kinase C delta. Biochem. J. 397, 109–120 10.1042/BJ20060354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturrioz X., Parker P. J. (2007). PKCzetaII is a target for degradation through the tumour suppressor protein pVHL. FEBS Lett. 581, 1397–1402 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan M., Haberberger T., Gervasi D. C., Michelson K. S., Gunzler V., Kondo K., Yang H., Sorokina I., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2002). Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 13459–13464 10.1073/pnas.192342099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan M., Kondo K., Yang H., Kim W., Valiando J., Ohh M., Salic A., Asara J. M., Lane W. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2001). HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 292, 464–468 10.1126/science.1059817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola P., Mole D. R., Tian Y. M., Wilson M. I., Gielbert J., Gaskell S. J., Kriegsheim A., Hebestreit H. F., Mukherji M., Schofield C. J., Maxwell P. H., Pugh C. W., Ratcliffe P. J. (2001). Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292, 468–472 10.1126/science.1059796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. (1998). The beta-adrenoceptor. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 158, S146–S153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorissen R. N., Walker F., Pouliot N., Garrett T. P., Ward C. W., Burgess A. W. (2003). Epidermal growth factor receptor: mechanisms of activation and signalling. Exp. Cell Res. 284, 31–53 10.1016/S0014-4827(02)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2002). Molecular basis of the VHL hereditary cancer syndrome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 673–682 10.1038/nrc885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T., Conrad M. N., Yan Q., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (1999a). The Rbx1 subunit of SCF and VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase activates Rub1 modification of cullins Cdc53 and Cul2. Genes Dev. 13, 2928–2933 10.1101/gad.13.22.2928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamura T., Koepp D. M., Conrad M. N., Skowyra D., Moreland R. J., Iliopoulos O., Lane W. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Elledge S. J., Conaway R. C., Conaway R. C., Harper J. W., Conaway J. W. (1999b). Rbx1, a component of the VHL tumor suppressor complex and SCF ubiquitin ligase. Science 284, 657–661 10.1126/science.284.5414.657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K., Kim W. Y., Lechpammer M., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2003). Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol. 1, E83. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo K., Klco J., Nakamura E., Lechpammer M., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2002). Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell 1, 237–246 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00043-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucejova B., Pena-Llopis S., Yamasaki T., Sivanand S., Tran T. A., Alexander S., Wolff N. C., Lotan Y., Xie X. J., Kabbani W., Kapur P., Brugarolas J. (2011). Interplay between pVHL and mTORC1 pathways in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 9, 1255–1265 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A. V., Meller J., Schnell P. O., Nash J. A., Ignacak M. L., Sanchez Y., Conaway J. W., Conaway R. C., Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F. (2003). von Hippel-Lindau protein binds hyperphosphorylated large subunit of RNA polymerase II through a proline hydroxylation motif and targets it for ubiquitination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2706–2711 10.1073/pnas.0436037100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y., Qiao M., Song M., Weintraub S. T., Shiio Y. (2011). Quantitative proteomics identifies the Myb-binding protein p160 as a novel target of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. PLoS One 6, e16975. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Schloss D. J., Jarvis L., Krasnow M. A., Swain J. L. (2001). Inhibition of angiogenesis by a mouse sprouty protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4128–4133 10.1074/jbc.M008521200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J., Lattouf J. B., Xanthopoulos J., Linehan W. M., Bottaro D. P., Vasselli J. R. (2008). von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene loss in renal cell carcinoma promotes oncogenic epidermal growth factor receptor signaling via Akt-1 and MEK-1. Eur. Urol. 54, 845–853 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkowitz G., Waterman H., Ettenberg S. A., Katz M., Tsygankov A. Y., Alroy I., Lavi S., Iwai K., Reiss Y., Ciechanover A., Lipkowitz S., Yarden Y. (1999). Ubiquitin ligase activity and tyrosine phosphorylation underlie suppression of growth factor signaling by c-Cbl/Sli-1. Mol. Cell 4, 1029–1040 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80231-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levkowitz G., Waterman H., Zamir E., Kam Z., Oved S., Langdon W. Y., Beguinot L., Geiger B., Yarden Y. (1998). c-Cbl/Sli-1 regulates endocytic sorting and ubiquitination of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Genes Dev. 12, 3663–3674 10.1101/gad.12.23.3663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F., Shi J., Liu H., Zhang J., Zhang P. L., Wang H. L., Yang X. J., Schuerch C. (2008). Immunohistochemical detection of the von Hippel-Lindau gene product (pVHL) in human tissues and tumors: a useful marker for metastatic renal cell carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the ovary and uterus. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 129, 592–605 10.1309/Q0FLUXFJ4FTTW1XR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan W. M., Zbar B. (2004). Focus on kidney cancer. Cancer Cell 6, 223–228 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo T. L., Yusoff P., Fong C. W., Guo K., McCaw B. J., Phillips W. A., Yang H., Wong E. S., Leong H. F., Zeng Q., Putti T. C., Guy G. R. (2004). The ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibitor and likely tumor suppressor proteins, sprouty 1 and sprouty 2 are deregulated in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 64, 6127–6136 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKie A. B., Douglas D. A., Olijslagers S., Graham J., Omar M. M., Heer R., Gnanapragasam V. J., Robson C. N., Leung H. Y. (2005). Epigenetic inactivation of the human sprouty2 (hSPRY2) homologue in prostate cancer. Oncogene 24, 2166–2174 10.1038/sj.onc.1208371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaylova O., Ignacak M. L., Barankiewicz T. J., Harbaugh S. V., Yi Y., Maxwell P. H., Schneider M., Van Geyte K., Carmeliet P., Revelo M. P., Wyder M., Greis K. D., Meller J., Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F. (2008). The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein and Egl-9-Type proline hydroxylases regulate the large subunit of RNA polymerase II in response to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 2701–2717 10.1128/MCB.01231-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosesson Y., Shtiegman K., Katz M., Zwang Y., Vereb G., Szollosi J., Yarden Y. (2003). Endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases is driven by monoubiquitination, not polyubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21323–21326 10.1074/jbc.C300096200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na X., Duan H. O., Messing E. M., Schoen S. R., Ryan C. K., di Sant’Agnese P. A., Golemis E. A., Wu G. (2003). Identification of the RNA polymerase II subunit hsRPB7 as a novel target of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. EMBO J. 22, 4249–4259 10.1093/emboj/cdg410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu X., Zhang T., Liao L., Zhou L., Lindner D. J., Zhou M., Rini B., Yan Q., Yang H. (2012). The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein regulates gene expression and tumor growth through histone demethylase JARID1C. Oncogene 31, 776–786 10.1038/onc.2011.266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohh M., Park C. W., Ivan M., Hoffman M. A., Kim T. Y., Huang L. E., Pavletich N., Chau V., Kaelin W. G. (2000). Ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor requires direct binding to the beta-domain of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 423–427 10.1038/35017054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda H., Saitoh K., Hirai S., Iwai K., Takaki Y., Baba M., Minato N., Ohno S., Shuin T. (2001). The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein mediates ubiquitination of activated atypical protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43611–43617 10.1074/jbc.M107880200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S., Claffey K. P., Dvorak H. F., Mukhopadhyay D. (1997). The von Hippel-Lindau gene product inhibits vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor expression in renal cell carcinoma by blocking protein kinase C pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27509–27512 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson S. J., Le Good J. A., Whelan R. D., Whitehead P., Parker P. J. (2004). Identification of PKCzetaII: an endogenous inhibitor of cell polarity. EMBO J. 23, 77–88 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razorenova O. V., Finger E. C., Colavitti R., Chernikova S. B., Boiko A. D., Chan C. K., Krieg A., Bedogni B., LaGory E., Weissman I. L., Broome-Powell M., Giaccia A. J. (2011). VHL loss in renal cell carcinoma leads to up-regulation of CUB domain-containing protein 1 to stimulate PKC{delta}-driven migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1931–1936 10.1073/pnas.1011777108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Li Y., Kufe D. (2002). Protein kinase C delta regulates function of the DF3/MUC1 carcinoma antigen in beta-catenin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17616–17622 10.1074/jbc.M111515200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reno E. M., Haughian J. M., Dimitrova I. K., Jackson T. A., Shroyer K. R., Bradford A. P. (2008). Analysis of protein kinase C delta (PKC delta) expression in endometrial tumors. Hum. Pathol. 39, 21–29 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini B. I. (2005). VEGF-targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Oncologist 10, 191–197 10.1634/theoncologist.10-3-191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockman H. A., Koch W. J., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002). Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature 415, 206–212 10.1038/415206a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraml P., Frew I. J., Thoma C. R., Boysen G., Struckmann K., Krek W., Moch H. (2009). Sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma but not the papillary type is characterized by severely reduced frequency of primary cilia. Mod. Pathol. 22, 31–36 10.1038/modpathol.2008.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G. L. (2003). Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 721–732 10.1038/nrc1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G. L. (2007). Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci. STKE 2007, cm8. 10.1126/stke.4072007cm8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G. L. (2010). Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene 29, 625–634 10.1038/onc.2009.441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K., Gunaratnam L., Morley M., Franovic A., Mekhail K., Lee S. (2005). Silencing of epidermal growth factor receptor suppresses hypoxia-inducible factor-2-driven VHL-/- renal cancer. Cancer Res. 65, 5221–5230 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins C. E., Kaelin W. G., Jr., Pavletich N. P. (1999). Structure of the VHL-ElonginC-ElonginB complex: implications for VHL tumor suppressor function. Science 284, 455–461 10.1126/science.284.5413.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterluty H., Mayer C. E., Setinek U., Attems J., Ovtcharov S., Mikula M., Mikulits W., Micksche M., Berger W. (2007). Down-regulation of sprouty2 in non-small cell lung cancer contributes to tumor malignancy via extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol. Cancer Res. 5, 509–520 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Yamanaka T., Hirose T., Manabe N., Mizuno K., Shimizu M., Akimoto K., Izumi Y., Ohnishi T., Ohno S. (2001). Atypical protein kinase C is involved in the evolutionarily conserved par protein complex and plays a critical role in establishing epithelia-specific junctional structures. J. Cell Biol. 152, 1183–1196 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavner F. J., Simpson R., Tashiro S., Favier D., Jenkins N. A., Gilbert D. J., Copeland N. G., Macmillan E. M., Lutwyche J., Keough R. A., Ishii S., Gonda T. J. (1998). Molecular cloning reveals that the p160 Myb-binding protein is a novel, predominantly nucleolar protein which may play a role in transactivation by Myb. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 989–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma C. R., Toso A., Gutbrodt K. L., Reggi S. P., Frew I. J., Schraml P., Hergovich A., Moch H., Meraldi P., Krek W. (2009). VHL loss causes spindle misorientation and chromosome instability. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 994–1001 10.1038/ncb1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umebayashi K., Stenmark H., Yoshimori T. (2008). Ubc4/5 and c-Cbl continue to ubiquitinate EGF receptor after internalization to facilitate polyubiquitination and degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3454–3462 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-0988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Roche O., Yan M. S., Finak G., Evans A. J., Metcalf J. L., Hast B. E., Hanna S. C., Wondergem B., Furge K. A., Irwin M. S., Kim W. Y., Teh B. T., Grinstein S., Park M., Marsden P. A., Ohh M. (2009). Regulation of endocytosis via the oxygen-sensing pathway. Nat. Med. 15, 319–324 10.1038/nm.1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman H., Katz M., Rubin C., Shtiegman K., Lavi S., Elson A., Jovin T., Yarden Y. (2002). A mutant EGF-receptor defective in ubiquitylation and endocytosis unveils a role for Grb2 in negative signaling. EMBO J. 21, 303–313 10.1093/emboj/21.3.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Xiao K., Whalen E. J., Forrester M. T., Freeman R. S., Fong G., Gygi S. P., Lefkowitz R. J., Stamler J. S. (2009). Oxygen-regulated beta(2)-adrenergic receptor hydroxylation by EGLN3 and ubiquitylation by pVHL. Sci. Signal. 2, ra33. 10.1126/scisignal.2000444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Minamishima Y. A., Yan Q., Schlisio S., Ebert B. L., Zhang X., Zhang L., Kim W. Y., Olumi A. F., Kaelin W. G., Jr. (2007). pVHL acts as an adaptor to promote the inhibitory phosphorylation of the NF-kappaB agonist Card9 by CK2. Mol. Cell 28, 15–27 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden Y., Sliwkowski M. X. (2001). Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 127–137 10.1038/35052073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi Y., Mikhaylova O., Mamedova A., Bastola P., Biesiada J., Alshaikh E., Levin L., Sheridan R. M., Meller J., Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F. (2010). von Hippel-Lindau-dependent patterns of RNA polymerase II hydroxylation in human renal clear cell carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 5142–5152 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yigzaw Y., Cartin L., Pierre S., Scholich K., Patel T. B. (2001). The C terminus of sprouty is important for modulation of cellular migration and proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 22742–22747 10.1074/jbc.M100123200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Yang H. (2011). The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein promotes c-Cbl-independent(poly)-ubiquitylation and degradation of the activated EGFR. PLoS ONE 6, e23936. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer M., Doucette D., Siddiqui N., Iliopoulos O. (2004). Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor is sufficient for growth suppression of VHL-/- tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 2, 89–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]