Abstract

Moths produce species-specific sex pheromones to attract conspecific mates. The biochemical processes that comprise sex pheromone biosynthesis are precisely regulated and a number of gene products are involved in this biosynthesis and regulation. In recent years, at least 300 EST clones have been isolated from Bombyx mori pheromone gland (PG) specific cDNA libraries with some of those clones [i.e., B. mori PG-specific desaturase 1 (Bmpgdesat1), PG-specific fatty acyl reductase, PG-specific acyl-CoA-binding protein, B. mori fatty acid transport protein, B. mori lipid storage droplet protein-1] characterized and demonstrated to play a role in sex pheromone production. However, most of the EST clones have yet to be fully characterized and identified. To develop an efficient system for analyzing sex pheromone production-related genes, we investigated the feasibility of a novel gene analysis system using the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1 that should contain a PG-specific gene promoter in conjunction with piggyBac vector-mediated germ line transformation. As a result, we have been able to obtain expression of our reporter gene (enhanced green fluorescent protein) in the PG but not in other tissues of transgenic B. mori. Current results indicate that we have successfully constructed a novel in vivo gene analysis system for sex pheromone production in B. mori.

Keywords: Bombyx mori, pheromone gland, EST analysis, piggyBac, germ line transformation

Introduction

Many species of moths (Insecta: Lepidoptera) produce and release sex pheromones, which are species-specific multi-component blends of semiochemicals, that attract conspecific mates (Tamaki, 1985). A major class of sex pheromones produced by these female moths has been characterized by the presence of straight chain C10–C18 unsaturated aliphatic compounds containing an oxygenated functional group such as alcohol, aldehyde, or acetate ester. These components are synthesized de novo in the pheromone-producing cells from acetyl-CoA through fatty acid synthesis, chain shortening, desaturation, and reductive modification of the carbonyl carbon (Tillman et al., 1999). In this biosynthetic pathway, various combinations of limited chain shortening and regio- and stereo-specific desaturation steps are involved in the production of large numbers of species-specific pheromone blends in Lepidoptera. Physiologically, moth sex pheromone biosynthesis is regulated by pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN), a 33-amino acid neuropeptide amidated at its C terminus that originates from the subesophageal ganglion (Raina and Menn, 1993).

In the silkmoth Bombyx mori, the sex pheromone bombykol, (E, Z)-10,12-hexadecadien-1-ol, is synthesized during photophase starting from the day of eclosion in the single layered epidermal cells located beneath the endocuticle between the eighth and ninth abdominal segments (Ando et al., 1988; Fónagy et al., 2001). Bombykol is biosynthesized de novo from acetyl-CoA through palmitate, which is stepwise converted to bombykol by Δ11 desaturation, Δ10, 12 desaturation, and reduction (Ando et al., 1988).

The public B. mori EST databases constructed from 36 cDNA libraries prepared using various tissues contains 35,000 EST clones, which together yield more than 11,000 independent EST clones (Mita et al., 2003). At least 300 independent EST clones have been isolated from cDNA libraries of the pheromone gland (PG), and some of which have recently been characterized and shown to function in sex pheromone production. B. mori PG-specific desaturase 1 (Bmpgdesat1), initially referred to as Desat1 but since renamed, is a fatty acyl-CoA desaturase involved in Δ11 desaturation and Δ10, 12 desaturation (Yoshiga et al., 2000; Moto et al., 2004). PG-specific fatty acyl reductase (pgFAR) is involved the reduction step (Moto et al., 2003b). PG-specific acyl-CoA-binding protein (pgACBP) is involved in the incorporation of the pheromone precursor fatty acyl groups in the triacylglycerols that comprise the cytoplasmic lipid droplets (Matsumoto et al., 2001; Ohnishi et al., 2006), while B. mori fatty acid transport protein (BmFATP) plays a role in both triacylglycerol synthesis and lipid droplet accumulation throughout the uptake of extracellular fatty acids following activation to CoA thioesters in the pheromone-producing cells (Ohnishi et al., 2009). B. mori lipid storage droplet protein-1 (BmLsd1), which is a member of the PAT family of proteins, plays an essential role in triacylglycerol lipolysis in the pheromone-producing cells (Ohnishi et al., 2011). Despite these efforts, the potential role the vast number of EST clones have in sex pheromone production has yet to be clarified.

In B. mori, some experimental methods for gene analysis have been established. Transient gene transfer methods such as electroporation and baculovirus infection are powerful tools for gene promoter analysis because these methods are suitable for expressing a fluorescent protein as a reporter for a short period of time (Moto et al., 1999, 2003a; Shiomi et al., 2003, 2005). However, because these methods include potential negative effects due to electric damage or pathogenic damage due to viral infection, their suitability for characterizing target gene function is subject to question. On the other hand, germ line transformation methods using piggyBac transposase might be suitable for characterizing the function of target genes if the transgene product has no deleterious effect on the insect itself (Tamura et al., 2000). The combination of germ line transformation with tissue-specific or cell-specific gene promoters has the potential to provide exquisite experimental results (Thomas et al., 2002; Inoue et al., 2005; Yamagata et al., 2008). In this paper, we report on the isolation of a novel PG-specific gene promoter. In addition, we demonstrate the feasibility of a gene analysis system using this promoter in combination with the piggyBac transposon vector in B. mori, and show using an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) report that expression is specific to the PG of transgenic progeny.

Materials and Methods

Silkmoth strains

Two B. mori strains were used in this study. The inbred strain p50 was used to amplify the upstream regions of Bmpgdesat1 and pgFAR from genomic DNA via PCR. The pnd-w1 (RK) strain, which is a non-diapausing strain that has non-pigmented eggs and eyes, was used for germ line transformation. Larvae were reared on an artificial diet (Nihon Nosan, Japan) at 25°C under 16:8 (light:dark).

EST analysis

The public B. mori EST database (CYBERGATE)1 was used in this study. To determine the number of EST clones categorized as Bmpgdesat1, pgFAR, and pgACBP in each cDNA library, we performed blastn analysis using the EST database and DNA sequences corresponding to the open reading frame (ORF) of the three genes.

Construction of transfer vectors

When the following piggyBac vectors were constructed all of the PCR experiments were conducted using KOD-plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Japan) and PTC Thermo cycler (MJ Research, USA). The nucleotide sequences of all PCR products were confirmed by DNA sequencing. For construction of pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP, a 3,870-bp DNA fragment comprising the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1 was amplified by PCR from B. mori genomic DNA with the oligonucleotide primer pair, ds1USR-F1 (5′-AAGGCGCGCCGTACAGCCTACCGCTTAGCG-3′) and ds1USR-EGFP-R (5′-TGCTCACCATTTTAGTAATTTAGATTTC-3′), Figure 1. A 997-bp DNA fragment comprising the EGFP ORF and SV40 terminator was also amplified by PCR from pEGFP-1 (Clontech, USA) with the oligonucleotide primer pair, ds1USR-EGFP-F (5′-AATTACTAAAATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGG-3′) and SV40T-R (5′-AAGGCCGGCCATACATTGATGAGTTTGG-3′). Primers ds1USR-EGFP-F and ds1USR-EGFP-R were partially complementary to each other and were designed to connect the 3′ end of the above PCR product containing the upstream region sequence of Bmpgdesat1 and the 5′ end of the above PCR product containing the EGFP ORF and the SV40 terminator. These two primers were also designed to overlap the initiation codon of Bmpgdesat1 and that of the EGFP ORF. To link these two DNA fragments, PCR amplification was performed with primers ds1USR-F and SV40T-R1 using the above two PCR products as templates. The resultant product was digested at the AscI site in the ds1USR-F primer and the FseI site in the SV40T-R1 primer and inserted into the corresponding site of a pBac (3xP3-DsRed2) transformation vector that carries inverted repeats of the piggyBac element for integration and the Discosoma red fluorescent protein (DsRed) gene under the control of an artificial eye-specific promoter (3xP3) as a selectable marker (Figure 2A). For construction of pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/pgFARUSR-EGFP, a 929-bp DNA fragment comprising the upstream region of B. mori pgFAR was amplified by PCR from B. mori genomic DNA with the oligonucleotide primer pair, pgFARUSR-F (5′-AAGGCGCGCCTCTCCATAAGCCTTACGAGG-3′) and pgFARUSR-EGFP-R (5′-TGCTCACCATCTTGGAGATTACGCGG-3′; Figure 1). A 997-bp DNA fragment comprising the EGFP ORF and the SV40 terminator was amplified by PCR from pEGFP-1 (Clontech, USA) with the oligonucleotide primer pair, pgFARUSR-EGFP-F (5′-AATCTCCAAGATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGG-3′) and SV40T-R1. Primers pgFARUSR-EGFP-F and pgFARUSR-EGFP-R were partially complementary to each other and were designed to connect the 3′ end of the above PCR product containing the upstream region sequence of pgFAR and the 5′ end of the above PCR product containing the EGFP ORF and the SV40 terminator. To link these two DNA fragments, PCR amplification was performed with primers pgFARUSR-F and SV40T-R1 using the above two PCR products as templates. The resultant product was digested at the AscI site in the pgFARUSR-F primer and the FseI site in the SV40T-R1 primer and inserted into the corresponding site of the pBac (3xP3-DsRed2) transformation vector (Figure 2B). For construction of pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-GW, a 3,868-bp DNA fragment comprising the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1 was amplified by PCR from B. mori genomic DNA with the oligonucleotide primer pair, ds1USR-F (5′-AAGGCGCGCCGTACAGCCTACCGCTTAGCG-3′) and ds1USR-R (5′-TTACGCGTTTAGTAATTTAGATTTC-3′). The resultant product was digested at the BssHII site in the ds1USR-F primer and the MluI site in the ds1USR-R primer and inserted into the corresponding site of the pMCS5 cloning vector (MoBioTec, Germany). The resultant plasmid was named pMCS5-Ds1USR. A 244-bp DNA fragment comprising the SV40 terminator was amplified by PCR from pEGFP-1 with the oligonucleotide primer pair, SV40T-F (5′-AAGCATGCGATCATAATCAGCCATACC-3′) and SV40T-R2 (5′-AAAAGCTTACATACATTGATGAGTT-3′). The resultant product was digested at the SphI site in the SV40T-F2 primer and the HindIII site in the SV40T-R2 primer and inserted into the corresponding site of the plasmid pMCS5-Ds1USR. The resultant plasmid was named pMCS5-Ds1USR-SV40T. A 1730-bp DNA fragment comprising the Gateway recombination cassette was amplified by PCR from pYES-DEST52 (Invitrogen) with the oligonucleotide primer pair, GW-F (5′-AAAGATCTACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGC-3′) and GW-R (5′-AAGGGCCCACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGC-3′). The resultant product was digested at the BglII site in the GW-F primer and the ApaI site in the GW-R and inserted into the corresponding site of the plasmid pMCS5-Ds1USR-SV40T. The resultant plasmid was named pMCS5-Ds1USR-GW-SV40T. A 5,968-bp DNA fragment comprising the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1, the Gateway recombination cassette and the SV40 terminator was amplified from pMCS5-Ds1USR-GW-SV40T by PCR with the oligonucleotide primer pair, ds1USR-F1 and SV40T-R1. The resultant product was digested at the AscI site in the pgFARUSR-F primer and the FseI site in the SV40T-R1 primer and inserted into the corresponding site of a pBac (3xP3-DsRed2) transformation vector (Figure 2C). For construction of pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP-BmLsd1, a 745-bp DNA fragment comprising the EGFP ORF was amplified by PCR from pEGFP-1 with the oligonucleotide primer pair, CACC-EGFP-F (5′-AAAGATCTACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGC-3′) and EGFP-A5-R (5′-AAGGGCCCACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGC-3′). A 1,113-bp DNA fragment comprising the lipid storage droplet protein (BmLsd1) ORF was also amplified by PCR from EST clone NRPG0891, which contains the BmLsd1 ORF sequence and is derived from the NRPG cDNA library (Table 1; Mita et al., 2003), with the oligonucleotide primer pair, A5-BmLsd1-F (5′-GCAGCTGCAG CTGCAATGCC GAATCTTGAA-3′) and BmLsd1-R (5′-TTAATTGACACCGTTAATGG-3′). The primers EGFP-A5-R and A5-BmLsd1-F were bridging primers and were designed to connect the 3′ end of the above PCR fragment containing the BmLsd1 ORF sequence and the 5′ end of the above PCR fragment containing the EGFP ORF sequence by the following PCR. To link these two DNA fragments, PCR amplification was performed with primers CACC-EGFP-F and BmLsd1-R using the above two PCR products as templates. The resultant product was cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Furthermore, this fusion protein ORF was cloned into the plasmid pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-GW by in vitro recombination using LR Clonase (Invitrogen, Figure 2D).

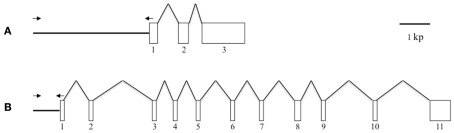

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the gene structures of Bmpgdesat1 and pgFAR. (A) Bmpgdesat1. (B) pgFAR. Exons and introns are indicated by boxes and broken lines connecting the exon boxes, respectively. Arrows indicate the position and direction of primers used to amplify the upstream region of the genes in this study. Numbers denote the exon number.

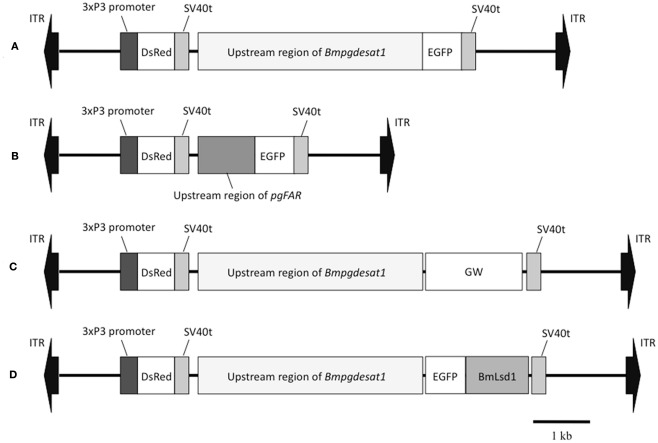

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the piggyBac vectors used in this study. (A) pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP. (B) pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/pgFARUSR-EGFP. (C) pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-GW. (D) pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP-BmLsd1. ITR, inverted terminal repeat of piggyBac transposon; DsRed, Discosoma red fluorescent protein; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescence protein coding region; SV40t, simian virus 40 terminator; GW, gateway recombination cassette.

Table 1.

List of the pheromone gland cDNA libraries in the B. mori EST database.

| Library name | Strain | Type |

|---|---|---|

| pg | Shuko × ryuhaku | General cDNA library |

| P5PG | p50 | General cDNA library |

| NRPG | p50 | Normalized cDNA library |

| fphe | p50 | Full-length cDNA library |

Injection of DNA into embryos

Plasmid DNAs for injection were purified using a Qiagen plasmid midi kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A vector plasmid was co-injected with the helper plasmid pHA3PIG, which served as the of the piggBac transposase (Kanda and Tamura, 1991; Tamura et al., 2000). Vector and helper plasmid (each 200 ng/μl) were dissolved in distilled water and microinjected into eggs collected 3–6 after oviposition. The injected eggs represented generation 0 (G0). After microinjection, the embryos were maintained at 25°C in a moist plastic case until hatching. The larvae were reared and G0 adults were mated with the same family or recipient strain. The resulting generation 1 (G1) progenies were screened for 3xP3 promoter-driven DsRed fluorescence in the stemma of their embryo. The DsRed-positive larvae G1 were reared to adults and EGFP fluorescence was confirmed in the PG. Fluorescence was observed using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, MZ FL III) equipped with filter sets for DsRed and EGFP. Fluorescence imaging was obtained with an AxioCam HRc camera (Carl Zeiss Microimaging GmbH) controlled by AxioVision Rel. 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging GmbH).

Confocal microscopy

Abdominal tips were dissected from female adults expressing the EGFP-BmLsd1 fusion protein and immersed in PBS. Under a dissecting microscope, the ovipositor portion of the abdominal tip was cut off and the resulting intersegmental membrane was spread open and trimmed by cleaning off all internal tissues attached (Fónagy et al., 2001). Fluorescence imaging was obtained with a Leica TCS NT confocal system using the 488-nm laser of an argon laser. Images were processed using Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Results

EST analysis

While more than 50 papers using transgenic B. mori have already been published, gene promoters related to PG-specific expression have yet to be reported. Based on Northern blot analysis, we previously reported that the genes, Bmpgdesat1, pgACBP, and pgFAR, are expressed predominantly in the PG and play essential roles in bombykol biosynthesis (Yoshiga et al., 2000; Matsumoto et al., 2001; Moto et al., 2003b, 2004). Consequently, we assumed that these three genes contain certain promoters for PG-specific expression. In the B. mori EST database (CYBERGATE)2, there are >11,000 independent EST clones which have been generated from 36 cDNA libraries containing four PG cDNA libraries prepared by our group (Table 1; Mita et al., 2003). To investigate whether these three genes were expressed exclusively in the B. mori PG, we examined the relationship between these three genes and the number of the categorized EST clones in every cDNA library (Table 2). Although EST clones classified as Bmpgdesat1 were present in our PG cDNA libraries as well as the famL cDNA library (prepared from antenna and Maxillary Galea of fifth instar larvae), the ratio of the EST clones of the famL cDNA library was significantly lower than that of the PG cDNA libraries. EST clones classified as pgFAR were likewise also present in the MFB cDNA library that was prepared from microbe-infected fat bodies of fifth instar larvae. However, as above, the ratio of the pgFAR EST clones in the MFB cDNA library was much lower compared to the PG cDNA libraries. Moreover, no EST clone classified as pgFAR was identified in the cDNA libraries prepared from non-infected fat bodies. In contrast to the other two genes, EST clones classified as pgACBP were present in various tissues. Compared with Bmpgdesat1 and pgFAR, the ratio of the unexpected pgACBP EST clones was higher in other tissues. These results indicate that the gene promoters of Bmpgdesat1 and pgFAR could be exploited for PG-specific expression of target genes of interest in vivo, but not that of pgACBP.

Table 2.

The relationship between individual genes and the frequency of their identified EST clones amongst the cDNA libraries that comprise the B. mori EST database.

| Library name | Organ tissue | Developmental stage | Total no. of EST clones in the library | No. of Bmpgdesat1 EST clones (%) | No. of pgFAR EST clones (%) | No. of pgACBP EST clones (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pg | Pheromone gland | Newly eclosed adult | 468 | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.85) |

| P5PG | Pheromone gland | Newly eclosed adult | 811 | 10 (1.2) | 3 (0.37) | 9 (1.1) |

| NRPG | Pheromone gland | Newly eclosed adult | 1,520 | 12 (0.8) | 1 (0.064) | 11 (0.72) |

| fphe | Pheromone gland | Newly eclosed adult | 14,983 | 193 (1.3) | 26 (0.17) | 490 (3.3) |

| famL | Antenna + maxillary galea | Fifth-instar larva | 25,972 | 2 (0.0077) | 0 (0) | 54 (0.21) |

| caL | Corpora allata | Fifth-instar larva | 10,831 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.0092) |

| fcaL | Corpora allata | Fifth-instar larva | 33,462 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 58 (0.17) |

| fdpe | Diapause-destined embryos | 12–40 h after oviposition | 5,714 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.035) |

| fe10 | Embryo | 100 h after fertilization | 5,024 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.040) |

| fe8d | Embryo | 200 h after fertilization | 17,551 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (0.12) |

| fufe | Embryo | Unfertilized egg | 17,095 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 66 (0.39) |

| ffbm | Fat body | Fifth-instar larva | 9,843 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.33) |

| MFBP | Microbe-infected fat body | Fifth-instar larva | 5,846 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.017) | 6 (0.10) |

| fmxg | Maxillary galea | Fifth-instar larva | 4,367 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.023) |

| MSV3 | Middle silk gland | Fifth-instar larva | 4,829 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.062) |

| msgV | Middle silk gland | Fifth-instar larva | 632 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.16) |

| fmgV | Midgut | Fifth-instar larva | 38,020 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 23 (0.064) |

| fner | Nerve system + brain | Fifth-instar larva | 37,074 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 32 (0.086) |

| ovS3 | Ovary | Spinning stage | 2,711 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.037) |

| PSV3 | Posterior silk gland | Fifth-instar larva | 5,243 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.038) |

| fprW | Prothoracic gland | Wandering stage | 5,501 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.036) |

| ftes | Testis | Fifth-instar larva | 29,670 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.020) |

| fwgP | Wing | Pupal stage | 18,225 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 23 (0.13) |

| wdS2 | Wing disk | Spinning stage | 760 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.13) |

| Total no. | 296,152 | 220 | 31 | 853 |

Transformation experiments

Because the promoter regions of Bmpgdesat1 and pgFAR have not been identified, we tried to obtain DNA sequence information for the upstream regions of these genes by using the Kaikoblast database3. The size of the defined upstream regions for Bmpgdesat1 (GenBank accession numbers: AB693932) and pgFAR was 3,844 and 929-bp, respectively (Figure 1). To confirm whether the upstream regions contained PG-specific gene promoters, the corresponding DNA fragments were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA from the p50 strain with each fragment linked to the EGFP coding region and the SV40 terminator. Each expression cassette was then inserted into the cloning sites of a piggyBac vector, pBac (3xP3)-DsRed2 (Inoue et al., 2005). The resultant transformation vectors were named pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP and pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/pgFARUSR-EGFP (Figures 2A,B). These vectors were separately co-injected with a piggyBac transposase plasmid into pre-blastodermal eggs of B. mori pnd-w1 (RK) strain. Of the 686 eggs injected with the pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR]EGFP plasmid, 348 larvae survived to the first larval stage (Table 3). We recovered 114 females and 87 males. After sibling mating, five of the G0 mating yielded progeny larvae with DsRed fluorescent eyes. The yield of mating in G0 adults with transformed gametes was 5.3% (Table 3). Three lines of DsRed-positive G1 females survived to adult. In two of these lines, EGFP fluorescence was detected in the PGs (Table 4; Figure 3), but not in other tissues (data not shown). We also confirmed that the Bmpgdesat1 gene promoter did not drive expression in various tissues at different developmental stages (e.g., embryo, larvae, pupae, adult) for DsRed-positive G2 females (data not shown). This result indicates that the PG-specific gene promoter resides within the 3,844-bp DNA sequence corresponding to the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1. Of the 803 eggs injected with the pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/pgFARUSR-EGFP plasmid, 348 larvae survived to the first larval stage (Table 3). We recovered 79 females and 79 males. After sibling mating, 11 of the G0 mating yielded progeny larvae with DsRed fluorescent eyes. This yield was 13.6% (Table 3). Six lines of DsRed-positive G1 females survived to adult. However, EGFP fluorescence was not detected in the PGs of all of the lines (Table 4). Because we confirmed that the EGFP reporter gene was specifically expressed in the PG of B. mori by using the above-mentioned 3,844-bp DNA sequence in conjunction with the conventional piggyBac transposon system, we next sought to construct a novel piggyBac vector pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-GW containing the 3,844-bp DNA sequence and the Gateway recombination cassette (Figure 2C), which allows for various genes of interest to be fused to many reporters and tags through a simple and uniform procedure using the Gateway cloning technology (Walhout et al., 2000).

Table 3.

Results of construct DNA injections into pnd-w1 (RK) embryos.

| Injected construct DNA | Number of injected embryos | Number of hatched embryos | Number of fertile moths |

Number of total G1 broods | Number of DsRed-positive G1 broods | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||||

| pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP | 686 | 348 (50.7%) | 114 | 87 | 95 | 5 (5.3%) |

| pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/pgFARUSR-EGFP | 803 | 276 (34.3%) | 79 | 79 | 81 | 11 (13.6%) |

| pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP-BmLsd1 | 522 | 122 (23.4%) | 27 | 31 | 26 | 2 (7.7%) |

Table 4.

Number of G1 GFP-positive adults.

| Lines | No. of DsRed-positive G1 larvae | No. of DsRed-positive moths |

No. of GFP-positive Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | |||

| Ds1USR-EGFP no. 23 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Ds1USR-EGFP no. 25 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ds1USR-EGFP no. 28 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ds1USR-EGFP no. 82 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ds1USR-EGFP no. 89 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 19 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 20 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 23 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 26 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 29 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 32 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 45 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 51 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| pgFARUSR-EGFP no. 52 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ds1USR-EGFP-BmLsd1 no. 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Ds1USR-EGFP-BmLsd1 no. 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

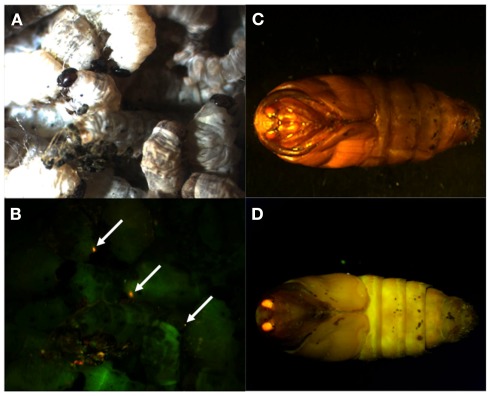

Figure 3.

DsRed expression in G1 transgenic animals. DsRed expression was visible in the stemmata of larvae (A,B) and the compound eyes of pupa (C,D). (A,C) Bright-field images. (B,D) Fluorescence images. Arrows indicate DsRed expression in the stemmata.

Expression and localization of an EGFP fusion protein

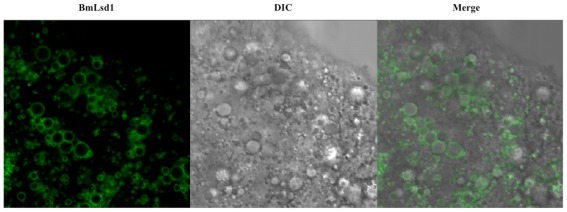

As an application of the gene transformation system in this study, we sought to investigate whether EGFP-tagged proteins responsible for sex pheromone production exhibit the expected sub-cellular localization pattern in the pheromone-producing cells of B. mori. NRPG0891 is one of the EST clones derived from the NRPG cDNA library (Table 1 and 2) and encodes a member of that PAT family of proteins known to localize to the surface of lipid droplets in Metazoan cells (Greenberg et al., 1991; Brasaemle et al., 1997; Heid et al., 1998; Wolins et al., 2001; Miura et al., 2002). This PAT family protein has recently been identified as BmLsd1 and shown to be involved in triacylglyceride lipolysis associated with sex pheromone production in B. mori (Ohnishi et al., 2011). Using immunocytochemistry, BmLsd1 was shown to localize to both the surface and core regions of lipid droplets, an inconsistency with the known localization pattern of mammalian PAT family proteins (Ohnishi et al., 2011). In the current study, we made a novel piggyBac vector pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP-BmLsd1 to express EGFP-tagged BmLsd1 in vivo in the pheromone-producing cells of B. mori (Figure 2D). Of the 522 eggs injected with the pBac/3xP3-DsRed2/Ds1USR-EGFP-BmLsd1 plasmid, 122 larvae survived to the first larval stage (Table 3). We recovered 27 females and 31 males. After sibling mating, two of the G0 matings yielded progeny larvae with DsRed eye fluorescence (Table 3). The yield of this mating was 7.7% (Table 3). Two lines of DsRed-positive G1 females were maintained to adulthood. In one line, EGFP fluorescence was detected in the PGs (Table 4). After the abdominal tip was dissected from the EGFP-positive female and the ovipositor tip removed, the obtained intersegmental membrane was spread open and trimmed by cleaning all internal tissues attached to allow for confocal microscopic examination. The differential interference contrast image showed that lipid droplets were abundant in the pheromone-producing cells as described previously (Figure 4; Fónagy et al., 1999, 2001). The green fluorescence image showed that BmLsd1 was localized exclusively to the surface of the lipid droplets in the pheromone-producing cells of B. mori (Figure 4). This result is consistent with the localization of other PAT family proteins in Metazoa (Greenberg et al., 1991; Brasaemle et al., 1997; Heid et al., 1998; Wolins et al., 2001; Miura et al., 2002). While the reason for the discrepancy with the immunocytochemistry results remains to be clarified, our present results on the specific localization of EGFP-tagged BmLsd1 strongly suggest that we can further apply this system, which uses a 3,844-bp DNA sequence corresponding to the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1 and a fluorescence protein like EGFP in conjunction with the conventional piggyBac-mediated transposon system, for the functional identification of genes expressed in PG cells.

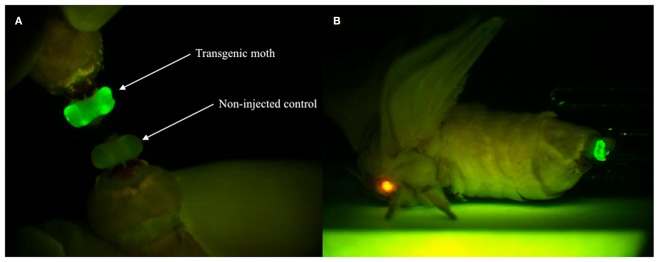

Figure 4.

Enhanced green fluorescent protein expression in the PG of G1 female adults. (A) EGFP expression was visible in the PG of transgenic moths but not non-injected controls. (B) The expressions of two reporter genes via whole-body fluorescence imaging. Red fluorescence is derived from DsRed expressed in the compound eye and green fluorescence is derived from EGFP expressed in the PG of the transgenic B. mori.

Discussion

To date, at least 300 independent EST clones have been isolated from four different types of separately prepared B. mori PG cDNA libraries (Table 1). Using heterologous gene expression systems, a number of these genes have been characterized and their functional roles in bombykol production determined (Yoshiga et al., 2000, 2002; Matsumoto et al., 2001; Moto et al., 2003b, 2004; Hull et al., 2009, 2010); however, they have yet to be characterized in vivo in the PG of B. mori to unequivocally demonstrate their physiological functional significance. To address this issue, we sought to construct an in vivo system that could be utilized for functional analysis of genes involved in sex pheromone production in B. mori. In the current study, we successfully showed that genes of interest could be expressed specifically in the PG cells by utilizing the conventional piggyBac transposon system in conjunction with a 3,844-bp DNA sequence corresponding to the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1. Interestingly, EGFP expression was not observed in the line 23 carrying the Ds1USR-EGFP construct even though DsRed expression was present. We inferred that the absence of EGFP expression was due to the conventional chromosomal position effect as previously reported (Suzuki et al., 2005). On the other hand, we could not confirm the expression of the EGFP reporter gene in PG when we used the 929-bp DNA sequence corresponding to the upstream region of pgFAR in this study. We were unable to adequately determine whether the PG-specific gene promoter is contained within the 929-bp DNA sequence corresponding to the upstream region of pgFAR because the number of the transgenic female moth examined in this study was too few. It is possible that the promoter region might not be contained in the fragment used in this study because the size of the fragment was too short or that the EGFP expression was not observed due to the chromosomal position effect.

Using this methodology with the 3,844-bp DNA sequence corresponding to the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1, we examined the in vivo localization of BmLsd1 in the pheromone-producing cells of B. mori. BmLsd1 is an insect PAT family protein associated with cytoplasmic lipid droplets and plays an essential role in bombykol biosynthesis via triacylglycerol lipolysis following Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation (Ohnishi et al., 2011). In the previous study, BmLsd1 was shown using immunocytochemistry to localize to both the surface and core region of the lipid droplets (Ohnishi et al., 2011). In the current study, however, EGFP-tagged BmLsd1 localized specifically to the surface of the lipid droplets in PG cells, a distribution consistent with other general mammalian PAT family proteins (Figure 5; Greenberg et al., 1991; Brasaemle et al., 1997; Heid et al., 1998; Wolins et al., 2001; Miura et al., 2002). Consequently, the results suggest that the piggyBac transposon system used in the current study is more suitable than the traditional immunocytochemistry method to localize BmLsd1 in the pheromone-producing cells and thus help clarify the dynamics of pheromone production-related proteins in vivo in the living pheromone-producing cells of B. mori. For example, the dynamics of PBAN receptor and stromal interaction molecule 1 (i.e., STIM1), which have been shown in transient expression assays using fluorescent reporter-based chimeras in Sf9 cells to change their sub-cellular localization in response to PBAN stimulation (Hull et al., 2004, 2005, 2009, 2010), could be clearly demonstrated in vivo in B. mori PGs.

Figure 5.

Localization of BmLsd1 in the pheromone-producing cells of B. mori. Following dissection and trimming of the PG, pheromone-producing cells were analyzed by confocal microscopy. EGFP-BmLsd1 fluorescence image (BmLsd1), differential interference contrast image (DIC), and the merged image (merge) are shown.

Double-stranded RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) was originally applied in Caenorhabditis elegans and has been developed as a powerful tool for gene silencing in a range of organisms (Fire et al., 1998; Hannon, 2002; Agrawal et al., 2003). In B. mori, injection of dsRNAs for target genes provided unequivocal demonstrations for the roles of Bmpgdesat1, pgFAR, pgACBP, and PBANR in sex pheromone production (Ohnishi et al., 2006). This simple in vivo system using developing B. mori could also be applied to elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying sex pheromone production in other Lepidoptera if DNA sequences of target genes are available. However, some genes related to sex pheromone production could be expressed in tissues other than PG (Matsumoto et al., 2001; Yoshiga et al., 2002; Ohnishi et al., 2009, 2011). In addition, because the insect circulatory system is an open system where hemolymph flows freely inside the body cavity, injection of target gene dsRNAs into the hemolymph might have unfavorable knockdown effects on tissues other than the PG. To prevent such side effects, our PG-specific gene expression system could be adapted as a novel in vivo PG-specific RNAi system that specifically expresses PG restricted dsRNAs for the target gene.

Sex pheromone production in B. mori is regulated by PBAN, which is released into the hemolymph after eclosion and acts directly on the PG to stimulate bombykol biosynthesis (Fónagy et al., 1992; Matsumoto et al., 2009). In contrast, transcriptional levels of the three pheromone production-related genes, Bmpgdesat1, pgFAR, and pgACBP, which are expressed predominantly in the PG, are synchronously up-regulated on the day prior to eclosion, indicating that transcription of these genes is regulated by factors other than PBAN (Yoshiga et al., 2000; Matsumoto et al., 2001; Moto et al., 2003b). It has been demonstrated that β-d-glucosyl-O-l-tyrosine, a humoral factor that appears in the pupal hemolymph 1 day prior to eclosion, regulates pgACBP transcription (Ohnishi et al., 2005). Surprisingly, while β-d-glucosyl-O-l-tyrosine titers rise dramatically prior to eclosion and reach the maximum level on the day preceding eclosion, this factor had no effect on the transcription of pgFAR and Bmpgdesat1, indicating that the transcriptional mechanism of pgACBP is different from that of pgFAR and Bmpgdesat1 (Matsumoto et al., 2010). The results of EST analysis in this study also suggest this discrepancy because almost all of the EST clones classified as Bmpgdesat1 and pgFAR are obtained from the PG, whereas pgACBP EST clones are present in various tissues (Table 2). In this study, PG-specific expression of an EGFP reporter gene was observed when using a 3,844-bp DNA sequence corresponding to the upstream region of Bmpgdesat1 but not the 929-bp DNA sequence corresponding to that of pgFAR, indicating that the 3,844-bp DNA sequence contains a transcriptional element involved in PG-specific gene expression. Further studies are needed to investigate the broader region surrounding pgFAR to identify the transcription element involved in the PG-specific expression of pgFAR (Figure 4). Consequently, it has yet to be determined whether the transcriptional mechanisms of the two respective genes are the same or not. It is possible that the transcriptional element in the 3,844-bp DNA sequence is novel as database searches failed to identify a transcriptional element. Therefore, further gene promoter analysis of Bmpgdesat1 may define the novel transcriptional element and clarify a novel molecular mechanism of sex pheromone production apart from the PBAN signal transduction cascade.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Toshiki Tamura, Dr. Tishio Kanda, Dr. Hideki Sezutsu, Dr. Keiro Uchino, Dr. Masataka Suzuki, Masaaki Kurihara, Satoko Yasuda, and Kana Hashimoto for help with the preparation of transgenic animals. This research was supported by the Bioarchitect Research Program and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (C) (20580058).

Footnotes

References

- Agrawal N., Dasaradhi P. V., Mohmmed A., Malhotra P., Bhatnagar R. K., Mukherjee S. K. (2003). RNA interference: biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 657–685 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.657-685.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando T., Hase R., Funayoshi A., Arima R., Uchiyama M. (1988). Sex pheromone biosynthesis from C14-hexadecanoic acid in the silkworm moth. Agric. Biol. Chem. 52, 141–147 10.1271/bbb1961.52.141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brasaemle D. L., Barber T., Wolins N. E., Serrero G., Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Londos C. (1997). Adipose differentiation-related protein is an ubiquitously expressed lipid storage droplet-associated protein. J. Lipid Res. 38, 2249–2263 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M. K., Kostas S. A., Driver S. E., Mello C. C. (1998). Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811 10.1038/35888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fónagy A., Matsumoto S., Uchiumi K., Orisaka C., Mitsui T. (1992). Action of pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide on pheromone glands of Bombyx mori and Spodoptera litura. J. Pest. Sci. 17, 47–54 10.1584/jpestics.17.S47 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fónagy A., Yokoyama N., Matsumoto S. (2001). Physiological status and change of cytoplasmic lipid droplets in the pheromone-producing cells of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera, Bombycidae). Arthropod. Struct. Dev. 30, 113–123 10.1016/S1467-8039(01)00027-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fónagy A., Yokoyama N., Okano K., Tatsuki S., Maeda S., Matsumoto S. (1999). Pheromone-producing cells in the silkmoth, Bombyx mori: identification and their morphological changes in response to pheromonotropic stimuli. J. Insect Physiol. 46, 735–744 10.1016/S0022-1910(99)00162-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg A. S., Egan J. J., Wek S. A., Garty N. B., Blanchette-Mackie E. J., Londos C. (1991). Perilipin, a major hormonally regulated adipocyte-specific phosphoprotein associated with the periphery of lipid storage droplets. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 11341–11346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon G. J. (2002). RNA interference. Nature 418, 244–251 10.1038/418244a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heid H. W., Moll R., Schwetlick I., Rackwitz H. R., Keenan T. W. (1998). Adipophilin is a specific marker of lipid accumulation in diverse cell types and diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 294, 309–321 10.1007/s004410051181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull J. J., Lee J. M., Kajigaya R., Matsumoto S. (2009). Bombyx mori homologs of STIM1 and Orai1 are essential components of the signal transduction cascade that regulates sex pheromone. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31200–31213 10.1074/jbc.M109.044198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull J. J., Lee J. M., Matsumoto S. (2010). Functional role of STIM1 and Orai1 in silkmoth (Bombyx mori) sex pheromone production. Commun. Integr. Biol. 3, 240–242 10.4161/cib.3.3.11394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull J. J., Ohnishi A., Matsumoto S. (2005). Regulatory mechanisms underlying pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN)-induced internalization of the Bombyx mori PBAN receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334, 69–78 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull J. J., Ohnishi A., Moto K., Kawasaki Y., Kurata R., Suzuki M. G., Matsumoto S. (2004). Cloning and characterization of the pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide receptor from the silkmoth, Bombyx mori. Significance of the carboxyl terminus in receptor internalization. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51500–51507 10.1074/jbc.M408142200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S., Kanda T., Imamura M., Quan G. X., Kojima K., Tanaka H., Tomita M., Hino R., Yoshizato K., Mizuno S., Tamura T. (2005). A fibroin secretion-deficient silkworm mutant, Nd-sD, provides an efficient system for producing recombinant proteins. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35, 51–59 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda T., Tamura T. (1991). Microinjection method for DNA in early embryos of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, using air pressure. Bull. Natl. Inst. Seric. Entomol. Sci. 2, 31–46 [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S., Hull J. J., Ohnishi A. (2009). Molecular mechanisms underlying PBAN signaling in the silkmoth Bombyx mori. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1163, 464–468 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03646.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S., Ohnishi A., Lee J. M., Hull J. J. (2010). Unraveling the pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide (PBAN) signal transduction cascade that regulates sex pheromone production in moths. Vitam. Horm. 83, 425–445 10.1016/S0083-6729(10)83018-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S., Yoshiga T., Yokoyama N., Iwanaga M., Koshiba S., Kigawa T., Hirota H., Yokoyama S., Okano K., Mita K., Shimada T., Tatsuki S. (2001). Characterization of acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) in the pheromone gland of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 31, 603–609 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00165-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita K., Morimyo M., Okano K., Koike Y., Nohata J., Kawasaki H., Kadono-Okuda K., Yamamoto K., Suzuki M. G., Shimada T., Goldsmith M. R., Maeda S. (2003). The construction of an EST database for Bombyx mori and its application. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14121–14126 10.1073/pnas.2234984100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura S., Gan J. W., Brzostowski J., Parisi M. J., Schultz C. J., Londos C., Oliver B., Kimmel A. R. (2002). Functional conservation for lipid storage droplet association among perilipin, ADRP, and TIP47 (PAT)-related proteins in mammals, Drosophila, and Dictyostelium. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32253–32257 10.1074/jbc.M204410200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moto K., Abdel Salam S. E., Sakurai S., Iwami M. (1999). Gene transfer into insect brain and cell-specific expression of bombyxin gene. Dev. Genes Evol. 209, 447–450 10.1007/s004270050277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moto K., Kojima H., Kurihara M., Iwami M., Matsumoto S. (2003a). Cell-specific expression of enhanced green fluorescence protein under the control of neuropeptide gene promoters in the brain of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, using Bombyx mori nucleopolyhedrovirus-derived vectors. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33, 7–12 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00185-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moto K., Yoshiga T., Yamamoto M., Takahashi S., Okano K., Ando T., Nakata T., Matsumoto S. (2003b). Pheromone gland-specific fatty-acyl reductase of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9156–9161 10.1073/pnas.1531993100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moto K., Suzuki M. G., Hull J. J., Kurata R., Takahashi S., Yamamoto M., Okano K., Imai K., Ando T., Matsumoto S. (2004). Involvment of a bifunctional fatty-acyl desaturase in the biosynthesis of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori, sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8631–8636 10.1073/pnas.0402056101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi A., Hashimoto K., Imai K., Matsumoto S. (2009). Functional characterization of the Bombyx mori fatty acid transport protein (BmFATP) within the silkmoth pheromone gland. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5128–5136 10.1074/jbc.M806072200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi A., Hull J. J., Kaji M., Hashimoto K., Lee J. M., Tsuneizumi K., Suzuki T., Dohmae N., Matsumoto S. (2011). Hormone signaling linked to silkmoth sex pheromone biosynthesis involves Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-mediated phosphorylation of the insect PAT family protein Bombyx mori lipid storage droplet protein-1 (BmLsd1). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24101–24112 10.1074/jbc.M111.250555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi A., Hull J. J., Matsumoto S. (2006). Targeted disruption of genes in the Bombyx mori sex pheromone biosynthetic pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4398–4403 10.1073/pnas.0511270103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi A., Koshino H., Takahashi S., Esumi Y., Matsumoto S. (2005). Isolation and characterization of a humoral factor that stimulates transcription of the acyl-CoA-binding protein in the pheromone gland of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4111–4116 10.1074/jbc.M502400200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina A. K., Menn J. J. (1993). Pheromone biosynthesis activating neuropeptide: from discovery to current status. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 22, 141–151 10.1002/arch.940220112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi K., Fujiwara Y., Atsumi T., Kajiura Z., Nakagaki M., Tanaka Y., Mizoguchi A., Yaginuma T., Yamashita O. (2005). Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) is a key modulator of the expression of the prothoracicotropic hormone gene in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. FEBS J. 272, 3853–3862 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04799.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi K., Kajiura Z., Nakagaki M., Yamashita O. (2003). Baculovirus-mediated efficient gene transfer into the central nervous system of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J. Insect Biotechnol. Sericol. 72, 149–155 [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. G., Funaguma S., Kanda T., Tamura T., Shimada T. (2005). Role of the male BmDSX protein in the sexual differentiation of Bombyx mori. Evol. Dev. 7, 58–68 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki Y. (1985). “Sex pheromones,” in Comprehensive Insect Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pharmacology, eds Kerkut G. A., Gilbert L. I. (New York: Pergamon; ), 9, 145–191 [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T., Thibert C., Royer C., Kanda T., Abraham E., Kamba M., Komoto N., Thomas J. L., Mauchamp B., Chavancy G., Shirk P., Fraser M., Prudhomme J. C., Couble P. (2000). Germline transformation of the silkworm Bombyx mori L. using a piggyBac transposon-derived vector. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 81–84 10.1038/71978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. L., Da Rocha M., Besse A., Mauchamp B., Chavancy G. (2002). 3xP3-EGFP marker facilitates screening for transgenic silkworm Bombyx mori L. from the embryonic stage onwards. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 247–253 10.1016/S0965-1748(01)00150-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman J. A., Seybold S. J., Jurenka R. A., Blomquist G. J. (1999). Insect pheromones – an overview of biosynthesis and endocrine regulation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29, 481–514 10.1016/S0965-1748(99)00016-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walhout A. J., Temple G. F., Brasch M. A., Hartley J. L., Lorson M. A., van den Heuvel S., Vidal M. (2000). GATEWAY recombinational cloning: application to the cloning of large numbers of open reading frames or ORFeomes. Meth. Enzymol. 328, 575–592 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)28419-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolins N. E., Rubin B., Brasaemle D. L. (2001). TIP47 associates with lipid droplets. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5101–5108 10.1074/jbc.M006775200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata T., Sakurai T., Uchino K., Sezutsu H., Tamura T., Kanzaki R. (2008). GFP labeling of neurosecretory cells with the GAL4/UAS system in the silkmoth brain enables selective intracellular staining of neurons. Zool. Sci. 25, 509–516 10.2108/zsj.25.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiga T., Okano K., Mita K., Shimada T., Matsumoto S. (2000). cDNA cloning of acyl-CoA desaturase homologs in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Gene 246, 339–345 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00047-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiga T., Yokoyama N., Imai N., Ohnishi A., Moto K., Matsumoto S. (2002). cDNA cloning of calcineurin heterosubunits from the pheromone gland of the silkmoth, Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 477–486 10.1016/S0965-1748(01)00125-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]