Abstract

The stigma associated with HIV/AIDS poses a psychological challenge to people living with HIV/AIDS. We hypothesized that that the consequences of stigma-related stressors on psychological well-being would depend on how people cope with the stress of HIV/AIDS stigma. Two hundred participants with HIV/AIDS completed a self-report measure of enacted stigma and felt stigma, a measure of how they coped with HIV/AIDS stigma, and measures of depression and anxiety, and self-esteem. In general, increases in felt stigma (concerns with public attitudes, negative self-image, and disclosure concerns) coupled with how participants reported coping with stigma (by disengaging from or engaging with the stigma stressor) predicted self-reported depression, anxiety, and self-esteem. Increases in felt stigma were associated with increases in anxiety and depression among participants who reported relatively high levels of disengagement coping compared to participants who reported relatively low levels of disengagement coping. Increases in felt stigma were associated with decreased self-esteem, but this association was attenuated among participants who reported relatively high levels of engagement control coping. The data also suggested a trend that increases in enacted stigma predicted increases in anxiety, but not depression, among participants who reported using more disengagement coping. Mental health professionals working with people who are HIV positive should consider how their clients cope with HIV/AIDS stigma and consider tailoring current therapies to address the relationship between stigma, coping, and psychological well-being.

Keywords: Coping, HIV/AIDS, stigma, self-esteem, depression

HIV infection significantly impacts people’s psychological well-being (Scott-Sheldon, Kalichman, Carey, & Fielder, 2008). Rates of current depression among persons with HIV have been estimated to be two to five times higher than rates of depression among persons who are HIV negative, and rates are as much as four times higher among women with HIV than women without HIV (Bing et al., 2001; Ciesla & Roberts, 2001; Morrison et al., 2002). People with HIV meet the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder at a rate almost eight times higher than a comparative U.S. sample (Bing, et al., 2001). People with HIV/AIDS also report feelings of self-doubt, self-consciousness, negative expectations about interpersonal interactions, and feelings of hopelessness and despair related to their illness (Kelly et al., 1993; Kylma, Vehvilainen-Julkunen, & Lahdevirta, 2001).

Understanding the experiences of living with HIV/AIDS that may contribute to these negative psychological outcomes can help to improve the quality of life of people with HIV/AIDS (Treisman & Angelino, 2004). One such experience may be the continued stigmatization of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States. Although a series of national surveys in the 1990s found a decrease in the stigmatization of people with HIV/AIDS over the decade, negative emotional responses toward people with HIV/AIDS such as fear and disgust persisted, as did the intention to socially avoid people with AIDS (Herek, Capitanio, & Widaman, 2002). This occurred despite an increased awareness of the true risks for HIV transmission (e.g., not through casual contact). The stigma associated with HIV/AIDS poses a unique psychological challenge to people living with the disease (Crepaz et al., 2008; Fife & Wright, 2000). The current study explores how coping with HIV/AIDS stigma influences the relationship between perceptions of HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being (Meyer, 2003; Miller & Major, 2000).

The psychological well-being of people with HIV/AIDS can be affected by HIV/AIDS stigma through direct experiences of prejudice and discrimination (known as enacted stigma) and by the anticipation of being stigmatized or the fear of being discriminated against (known as felt or perceived stigma; (Scambler, 1998). Previous research has shown a relationship between both enacted and felt HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being. Vanable, Carey, Blair and Littlewood (2006) found that people with HIV who reported high levels of enacted stigma (for example, being avoided, mistreated, or discriminated against) also reported more symptoms of depressed mood. This relationship between felt HIV/AIDS stigma and depression has been found in both adults and youths living with HIV/AIDS. Emlet (2007) found that adults in their fifties living with HIV/AIDS who experienced more felt stigma reported more depressed mood than people who reported experiencing less felt stigma. Similarly, symptoms of anxiety and depression in young HIV positive individuals were positively correlated with perceived negative reactions of others to their HIV status (Wright, Naar-King, Lam, Templin, & Frey, 2007).

The negative psychological effects of stigma may be more severe among people with HIV/AIDS than among people with other medical conditions. HIV was identified in a meta-analysis of 21 studies to be more stigmatized than other diseases (e.g., diabetes) as well as other stigmatized sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., genital herpes) (Lawless, Kippax, & Crawford, 1996). In a more recent comparison of cancer patients and people with HIV/AIDS, Fife and Wright (2000) found that patients with HIV/AIDS reported more experiences of enacted stigma including social rejection, social isolation, and financial insecurity associated with possible workplace discrimination than cancer patients did. People with HIV/AIDS also reported more experiences of internalized shame and lower self-esteem than cancer patients did (Fife & Wright, 2000).

One mechanism by which stigma can result in negative psychological symptoms is that being stigmatized is stressful. Stigma is stressful because other people have stereotyped expectancies about what stigmatized people are like, harbor prejudiced attitudes toward stigmatized people, and behave in a discriminatory manner toward stigmatized people (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Miller & Kaiser, 2001). People with HIV/AIDS may perceive many sources of stress related to their seropositive status, such as the ongoing demands of strict medical regimes, changes in nutrition, and the physical changes that accompany a chronic illness. The stigma of HIV/AIDS, however, may be a source of stress that is different from stressors related to the physical toll the disease takes. For example, the lifestyle changes noted above that many people with HIV/AIDS undergo may serve as a constant reminder of their stigma. Also, the possibility of experiencing prejudice and discrimination because of their HIV status adds a stress to infected people’s lives that other people who manage the stress of a chronic illness may not face (Miller & Kaiser, 2001; Miller & Major, 2000). Finally, the stigma of HIV/AIDS may be the dominant stressor in an infected person’s life. Pakenham and his colleagues (Pakenham, Dadds, & Terry, 1994, 1996; Pakenham & Rinaldis, 2002) have found that the most stressful problems reported by people living with HIV/AIDS were related to navigating challenging social situations including discrimination, stigma, confidentiality, and disclosure.

The results of the studies of HIV/AIDS stigma described above suggest that there is a consistent relationship between experiences of felt and enacted HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being. A recent meta-analysis (Logie & Gadalla, 2009) of 24 studies of people with HIV/AIDS showed that the correlation between high HIV/AIDS stigma and poorer mental health was moderate (r = −.40). The vast research on coping with stress suggests that individuals differ in their ability to cope with stress. Individuals with HIV/AIDS may differ in how vulnerable they are to the stressful effects of stigmatization. The goal of the present study was to investigate whether coping with HIV/AIDS stigma moderates the relationship between HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological outcomes.

The coping model that guides our theorizing assumes that coping is a self-regulatory effort aimed at reducing the adverse consequences of stressors, and draws on traditional distinctions between approach and avoidance responses to stressors (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001; Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000). Approach responses are characterized by efforts to engage with the source of stress and enhance a sense of personal control over the situation (primary control engagement coping) and/or adapt to the situation (secondary control engagement coping). Avoidance responses are characterized by efforts to disengage from the stressor through avoidance, denial, wishful thinking (disengagement coping). A growing body of research on coping with stigma has documented that stigmatized people use engagement and disengagement coping strategies to protect themselves from stressors that result from stigma (see (Major, Quinton, & McCoy, 2002; Miller & Kaiser, 2001). For example, stigmatized people protect their self-esteem from the negative consequences of prejudice and discrimination by blaming poor outcomes on prejudice (Crocker & Major, 1989), a form of voluntary secondary control coping involving cognitive restructuring. Stigmatized persons have also been shown to avoid situations that could result in their being stigmatized (Pinel, 1999; Swim, Cohen, & Hyers, 1998).

In general, using disengagement coping strategies is associated with negative psychological outcomes, whereas using engagement coping is associated with less psychological distress (see (Compas, Connor-Smith, Osowiecki, & Welch, 1997 )for a review). Among people with HIV/AIDS, using disengagement coping to deal with stress has been associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, emotional distress, and a less positive state of mind (Gonzalez, Solomon, Zvolensky, & Miller, 2010; Heckman et al., 2004; Turner-Cobb et al., 2002). In contrast, people with HIV/AIDS who used engagement coping strategies to deal with stress reported lower levels of depression and global distress, and higher levels of life satisfaction (Heckman, 2003; Pakenham & Rinaldis, 2001). Although the source of stress in the studies just described is HIV-related, it is often not specifically focused on the experience of HIV/AIDS stigma alone. Thus, it is still unclear how coping with the unique stigma of HIV/AIDS (as opposed to coping with other sources of stress related to HIV/AIDS) might affect whether HIV/AIDS stigma negatively impacts psychological health.

In the current study we hypothesized that the relationship between perceived HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being would be moderated by how people cope with HIV/AIDS stigma. Specifically, we hypothesized that people with HIV/AIDS who coped with the stress of HIV/AIDS stigma by disengaging from the stressor would experience more symptoms of depression and anxiety, and would report less self-esteem as they perceived more HIV/AIDS stigma. In contrast, people living with HIV/AIDS who coped with the stigma of HIV/AIDS by engaging with the stressor using primary control engagement (e.g., problem solving) or secondary control engagement (e.g., cognitive restructuring) coping strategies would report fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety and more self-esteem as they perceived more HIV/AIDS stigma.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and three people with HIV/AIDS participated in this study. Three participants were removed from analyses because of computer errors in recording the data, for a final sample size of 200 participants. Participants were recruited from medical care centers in Vermont, a major university-affiliated hospital in New Hampshire, and through AIDS service organizations in Vermont, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. The majority lived in Vermont (73.5%), were male (72%) and identified as White (81%). Forty-two percent of participants identified as exclusively heterosexual, and 42% of participants identified as exclusively homosexual. The remaining 16% of the sample identified as neither exclusively homosexual nor exclusively heterosexual, but instead somewhere on a continuum between the two classifications.

The mean age of participants was 43.18 years old (SD = 8.67 years) with a range of 18 to 64 years. All participants self-identified as being HIV-positive. Time since HIV diagnosis was calculated by subtracting the date of diagnosis from the date of participation. Eight participants did not enter their year of diagnosis or listed a year prior to 1982, before a diagnosis of HIV was recognized. One participant provided a current age and an age at diagnosis, and the difference between these two ages was substituted for time since diagnosis. Of those participants for whom time since diagnosis could be determined (n=192), the average time since diagnosis was 10.64 years (SD = 5.92 years). Mean replacement was used in subsequent analyses for participants who did not report a year of diagnosis or who reported a year earlier than 1982. Sixty-nine percent of the sample reported that they had been diagnosed with a condition that the Center for Disease Control and Prevention uses to classify people with HIV into the most severe clinical category, Category C (Castro et al., 1992).

Measures

HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale

Perceived HIV/AIDS stigma was measured with a revised version of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale (Bunn, Solomon, Miller, & Forehand, 2007) originally developed by developed by Berger, Ferrans and Lashley (2001). The revised measure eliminated the cross-loading of items onto multiple subscales, which increases the confidence that relationships between the subscales are a result of genuine association. The measure consists of four subscales measuring different effects of stigma. One subscale, the enacted stigma subscale (11 items), measures people’s actual experiences with HIV/AIDS stigma (e.g., I have lost friends by telling them I have HIV/AIDS.). The remaining three subscales measure aspects of felt or perceived stigma. The disclosure concerns subscale (8 items) measures the distress people feel about who knows they are HIV-positive (e.g., I am very careful who I tell that I have HIV/AIDS.). The concern with public attitudes subscale (6 items) assesses how the person with HIV/AIDS believes others view people with HIV/AIDS, in general (e.g., Most people believe a person who has HIV/AIDS is dirty.). The negative self-image subscale includes 7 items that measures how much HIV/AIDS stigma effects perceived self-worth (e.g., Having HIV/AIDS makes me feel that I am a bad person.). Participants indicated their agreement with each of the items on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), and mean scores were calculated for each subscale so that a higher score indicated more perceived stigma. Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales ranged from .90 to .97.

Response to Stress Questionnaire-HIV/AIDS Stigma

Participants’ efforts to cope with the stigma of HIV/AIDS were measured using the Response to Stress Questionnaire (Connor-Smith, et al., 2000), which is designed to assess coping responses to particular stressors. The scale can be tailored to direct the participants’ focus towards a particular source of stress. In this study, participants were directed to think about how the stigma of HIV/AIDS caused them to experience stress. Participants first reported different ways that the stigma of HIV/AIDS caused them stress. For each stressful problem, participants indicated how stressful the problem was for them and how much control they believed they had over the problem on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very). Participants were then directed to think about the problem they reported that was the most stressful to them as a reference for the rest of the questionnaire.

Participants read statements describing different coping strategies that could be used to deal with the stress of HIV/AIDS stigma. The different coping strategies presented to participants correspond to the model developed by Compas et al. (2001). Nine items assess the use of primary control engagement coping strategies, including problem solving (e.g., I try to think of different ways to deal with problems related to the stigma of HIV/AIDS.), emotional regulation (e.g., I do something to calm myself down when I am dealing with issues related to the stigma of HIV/AIDS.), and emotional expression (e.g., I let someone know how I feel.). Twelve items assess the use of secondary control engagement coping, including positive thinking (e.g., I tell myself I can get through this, that I will be okay.), cognitive restructuring (e.g., I tell myself things could be worse.), acceptance (e.g., I realize I just have to accept things the way they are.), and distraction (e.g., I imagine something really fun or exciting happening in my life.) to cope with HIV/AIDS stigma. Nine items assess the use of disengagement coping scale strategies, including avoidance (e.g., I try not to think about it, to forget all about it.), denial (e.g., When something related to the stigma of HIV/AIDS comes up, I say to myself, “this isn’t real.”), and wishful thinking (e.g., I wish that I were stronger, or better able to cope so that things would be different.). Response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot), and mean scores were calculated for each of the three coping strategies. Cronbach’s alpha for primary and secondary control engagement coping and disengagement coping scales ranged from .77–.80.

Symptom Check List-90-R (SCL-90-R)

The SCL-90-R (Derogatis, 1994) is a self-report measure that assesses people’s experiences with symptoms that are indicative of different psychological problems. Participants read ninety problems and indicate how much each problem has distressed or bothered them in the past seven days, including today, on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). For our analyses, we used the depression and anxiety subscales. The depression subscale consists of 13 items measuring how much participants experience dysphoric mood and affect (e.g., feeling blue and feeling no interest in things.). The anxiety subscale (10 items) assesses how much participants experience cognitive, affective, and physiological symptoms related to general anxiety (e.g., thoughts and images of a frightening nature and nervousness or shakiness inside.). Scale score were calculated by taking the mean of items for each subscale. Cronbach’s alphas for the depression and anxiety subscales were .93 and .92, respectively.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. We used the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to measure participants’ global self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1989). Participants indicated their agreement with statements about their self-worth (e.g., On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.) on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Participants’ scale scores were calculated by taking the mean of these items, with higher scores indicating more self-esteem. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .78.

Procedure

Participants met with a member of the research team either at the project site at the university or at another location, usually the recruitment site. The measures were administered via a computer program (MediaLab; (Jarvis, 2004). This was done to promote honest responses and to reduce random errors associated with paper and pencil administration (Catania, Gibson, Chitwood, & Coates, 1990). Upon arrival, participants read (or had read to them) a description of the study and gave their written consent to participate. With the help of the research assistant, participants familiarized themselves with the computer by answering practice questions unrelated to the study measures (e.g., food preferences). Once participants felt comfortable using the computer, the research assistant would leave to sit in an adjoining room (at the project site) or to sit so that the computer and the participants’ answers were out of view (at recruitment sites) to ensure the privacy of the participants, but still remain available for assistance. All participants were monetarily compensated for their time and travel expenses. This study was conducted in compliance with standards set forth by the University of Vermont Institutional Review Board.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Mean scores for the stigma, coping, and psychological well-being measures are shown in Table 1. This table also shows that all of the stigma subscales were positively correlated with each other (all r’s(199) ≥ .27and p’s ≤ .01). On average, participants scored higher on the disclosure concerns subscale than on the concern with public attitudes subscale (t(199) = 5.85, p ≤. 001, r = .41), the enacted stigma subscale(t(199) = 4.30, p ≤ .001, r = .30), and the negative self-image subscale (t(199) = 12.36, p ≤ .001, r = .85). Scores on the concerns with public attitudes subscale were higher than scores on the enacted stigma subscale (t(199) = 4.30, p ≤ .001, r = .30) and the negative self-image subscale (t(199) = 8.42, p ≤ .001, r = .58). Enacted stigma subscale scores were higher than negative self-image subscale scores (t(199) = 2.80, p ≤ .01, r = .20). Taken together, these results indicate that participants reported more experiences with felt stigma (particularly disclosure concerns and concerns with public attitudes) than enacted stigma.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Zero-Order Correlations of HIV/AIDS Stigma, Coping with HIV/AIDS Stigma and Psychological Well-Being

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | Mean | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enacted Stigma | – | .54** | .37** | .27** | .17* | −.09 | .40** | .34** | .32** | −.31** | −.06 | −.06 | .08 | 2.37 | .77 |

| 2 | Concern with Public Attitudes | – | .57** | .47** | .05 | −.08 | .53** | .50** | .42** | −.36** | −.16* | −.16 | −.07 | 2.59 | .60 | |

| 3 | Negative Self-Image | – | .46** | −.03 | −.16* | .53** | .50** | .47** | −.51** | −.10 | −.10 | −.25** | 2.20 | .77 | ||

| 4 | Disclosure Concerns | – | −.26** | −.10 | .37** | .24** | .21** | −.18* | −.05 | −.05 | −.14* | 2.87 | .72 | |||

| 5 | Primary Control Engagement Coping | – | .38** | .11 | .11 | .12 | −.01 | −.08 | .08 | .14 | 2.55 | .62 | ||||

| 6 | Secondary Control Engagement Coping | – | .06 | −.03 | −.02 | .21** | −.13 | .01 | .03 | 2.82 | .53 | |||||

| 7 | Disengagement Coping | – | .60** | .56** | −.51** | −.12 | −.15 | −.14* | 2.26 | .65 | ||||||

| 8 | Depression | – | .85** | −.57** | −.20** | −.15* | −.13 | 1.12 | .91 | |||||||

| 9 | Anxiety | – | −.48** | −.16** | −.16* | −.13 | .73 | .79 | ||||||||

| 10 | Self-Esteem | – | .05 | .24* | .07 | 3.05 | .57 | |||||||||

| 11 | Sex (1= female, 2 = male) | – | .11 | .02 | – | – | ||||||||||

| 12 | Age (in years) | – | .32** | 43.18 | 8.67 | |||||||||||

| 13 | Time Since diagnosis (in years) | – | 10.64 | 5.93 |

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

Primary control engagement coping and secondary control engagement coping were positively correlated with each other (r(199) = .38, p ≤ .01), but neither was correlated with disengagement coping (r(199) = .11 and .06, respectively, p ≥ .10). Participants reported using more secondary control engagement coping than primary control engagement coping (t(199) = −5.88, p ≤ .001, r = .41) or disengagement coping (t(199) = 9.66, p ≤ .001, r = .67), and reported using more primary control engagement coping than disengagement coping (t(199) = 4.78, p ≤ .001, r = .33).

Analysis of the SCL-90 (see Table 1) revealed that depression scores ranged from 0 to 3.85 and anxiety scores ranged from 0 to 3.20. Thirty-six percent of our sample had T-scores of 63 or higher on both the depression and the anxiety dimensions, indicating that they are at high risk for a psychiatric diagnosis in a normal population (Derogatis, 1994).

Depression and anxiety scores were strongly positively correlated with one another (r(200) = .85, p ≤ .01) and were both negatively correlated with self-esteem scores (r(200) = −.57 and −.48, p ≤ .01 for depression and anxiety, respectively). Women reported more symptoms of depression (M = 1.41, SD = 1.02) than men did (M = 1.01, SD = .84, t(198) = 2.61, p ≤ .01, r = .18) and they reported more symptoms of anxiety (M = .93, SD = .91) than men did (M = .65 , SD = .73 , t(198) = 2.24, p ≤ .05, r = .16).

Regression Analyses

We assessed the effects of perceived stigma and coping with stigma on psychological well-being with a series of multiple linear hierarchical regressions with depression, anxiety, and self-esteem serving as criterion in separate analyses. Although the criterion measures were correlated, and the comorbidity of anxiety and depression disorders is well documented, we analyzed them separately because there are different experiences associated with each that may be important in understanding the relationship between stigma, coping, and psychological outcomes. For example, anxiety is associated with feeling fearful and depression is associated with feeling low in energy (Endler, Denisoff, & Rutherford, 1998). There may be implications for how different coping strategies and experiences of stigma predict these symptoms individually that would be lost in an analysis of a combined variable representing psychological distress.

Each regression model shared the same basic structure. In the first step of each regression we conducted, we entered sex (females coded as “1”, males coded as “0”), age (in years), and time since diagnosis (in years) as control variables. Then, one of the stigma subscales and one of the coping subscales was entered in the second step (e.g., enacted stigma and disengagement coping, or disclosure concerns and primary control engagement coping). Finally, the interaction between the stigma subscale and the coping scale from the second step was calculated by taking the product of these two terms and entering this product in the third step. All continuous variables were centered prior to analysis.

Disengagement Coping, HIV/AIDS Stigma, and Psychological Well-being

We predicted that people with HIV/AIDS who used disengagement coping (e.g., avoidance) to deal with HIV/AIDS stigma would report more depression, more anxiety, and less self-esteem as their stigma increased. As can be seen in Table 2, the interactions between the felt stigma subscales (concern with public attitudes, negative self-image, and disclosure concerns) and disengagement coping predicted both anxiety and depression. The interaction between enacted stigma and disengagement coping did not predict depression, but approached significance in predicting anxiety (p = .06). None of the interactions between any of the stigma subscales with disengagement coping predicted self-esteem.

Table 2.

Summary of Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regression Analyses Psychological Well-being Predicting from Disengagement Coping and Stigma

| Depression | Anxiety | Self Esteem | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | |

| Enacted | ||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .05** | .06** | |||

| Sex (female) | .13* | .09 | .03 | |||

| Age | −.04 | −.06 | .19** | |||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.06 | −.05 | −.04 | |||

| Step 2 | .33*** | .29*** | .25*** | |||

| Coping | .52*** | .49*** | −.43*** | |||

| Stigma | .12 | .12 | −.14* | |||

| Step 3 | .01 | .01 | .00 | |||

| Interaction | .07 | .11 | −.01 | |||

| Total R2 | .40*** | .36*** | .30*** | |||

| Concern with Public Attitudes | ||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .05** | .06** | |||

| Sex (female) | .10 | .07 | .04 | |||

| Age | −.03 | −.05 | .18** | |||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.04 | −.03 | −.05 | |||

| Step 2 | .36*** | .30*** | .24*** | |||

| Coping | .44*** | .43*** | −.43*** | |||

| Stigma | .24*** | .17** | −.13 | |||

| Step 3 | .01* | .03** | .00 | |||

| Interaction | .11* | .17** | .04 | |||

| Total R2 | .43*** | .38*** | .30*** | |||

| Negative Self-Image | ||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .05** | .06** | |||

| Sex (female) | .13* | .10 | .04 | |||

| Age | .01 | −.02 | .15* | |||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.00 | .01 | −.11 | |||

| Step 2 | .35*** | .31*** | .31*** | |||

| Coping | .44*** | .41*** | −.33*** | |||

| Stigma | .23*** | .20** | −.34*** | |||

| Step 3 | .02** | .03** | .00 | |||

| Interaction | .15** | .18** | .04 | |||

| Total R2 | .44*** | .40*** | .36*** | |||

| Disclosure Concerns | ||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .05** | .06** | |||

| Sex (female) | .13* | .09 | .03 | |||

| Age | −.03 | −.06 | .19** | |||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.04 | .03 | −.06 | |||

| Step 2 | .32*** | .28*** | .23*** | |||

| Coping | .57*** | .54*** | −.50*** | |||

| Stigma | .02 | .01 | .03 | |||

| Step 3 | .02** | .03** | .00 | |||

| Interaction | .14** | .17** | −.00 | |||

| Total R2 | .40*** | .36*** | .29*** | |||

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

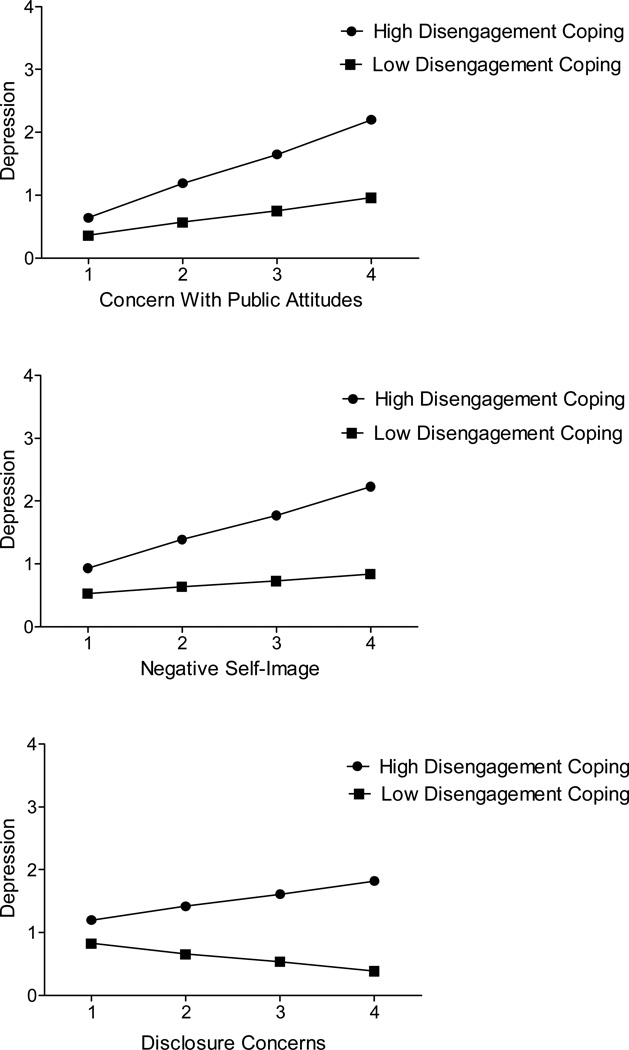

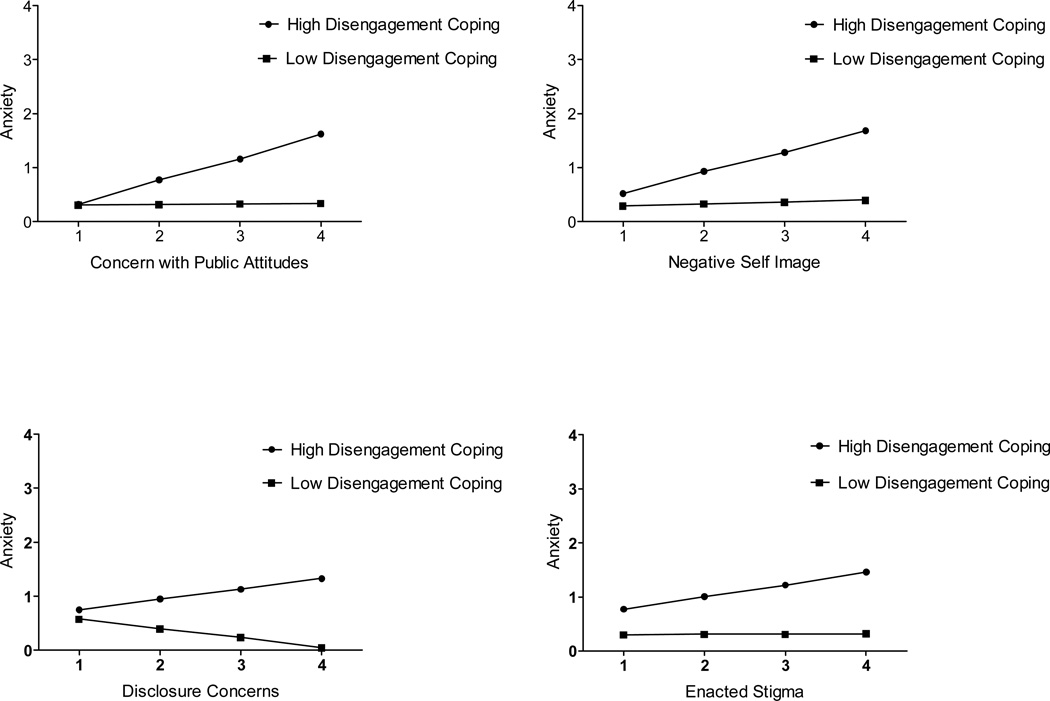

We examined the slopes of the significant interactions between stigma and disengagement coping by testing the simple slopes of stigma regressed on anxiety or depression at high (plus one standard deviation to the mean) and low (minus one standard deviation from the mean) levels of disengagement coping to see if they were significantly different from zero (Aiken & West, 1991; Hayes & Matthes, 2009). The results from the simple slopes analyses are reported in Table 3. A general pattern emerged for predictions of both depression and anxiety, which is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. When disengagement coping was high, increases in felt stigma (concern with public attitudes, negative self-image, and disclosure concerns) predicted increases in depression, though the slope for high disengagement coping and disclosure concerns was marginally significant (p = .06). When disengagement coping was low, increases in felt stigma did not predict changes in depression.

Table 3.

Summary of Simple Slopes for Significant Stigma X Coping Interactions

| Enacted Stigma |

Concern with Public Attitudes |

Negative Self Image | Disclosure Concerns | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | p | r | B | t | p | r | B | t | p | r | B | t | p | r | |

| Depression | ||||||||||||||||

| High Disengagement Coping | – | – | – | .52 | 4.12 | .00 | .28 | .43 | 4.57 | .00 | .31 | .21 | 1.90 | .06 | .13 | |

| Low Disengagement Coping | – | – | – | .20 | 1.63 | .10 | .12 | .10 | 1.02 | .31 | .07 | −.15 | −1.49 | .14 | .11 | |

| Anxiety | ||||||||||||||||

| High Disengagement Coping | .23 | 2.72 | .01 | .19 | .43 | 3.76 | .00 | .26 | .39 | 4.50 | .00 | .30 | .19 | 1.99 | .05 | .14 |

| Low Disengagement Coping | .01 | .05 | .96 | .00 | .01 | .09 | .93 | .01 | .04 | .38 | .71 | .03 | −.18 | −1.99 | .05 | .14 |

| Self-Esteem | ||||||||||||||||

| High Primary Control Engagement Coping |

– | – | – | −.17 | −1.91 | .06 | .13 | −.27 | −4.12 | .00 | .28 | – | – | – | ||

| Low Primary Control Engagement Coping |

– | – | – | −.42 | −5.52 | .00 | .37 | −.46 | −7.59 | .00 | .47 | – | – | – | ||

| High Secondary Control Engagement Coping |

– | – | – | −.09 | −1.17 | .25 | .08 | −.21 | −3.39 | .00 | .23 | .04 | .58 | .56 | .04 | |

| Low Secondary Control Engagement Coping |

– | – | – | −.55 | −6.50 | .00 | .42 | −.48 | −7.95 | .00 | .49 | −.22 | −3.10 | .00 | .22 | |

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of disengagement coping on the relationship between felt stigma and depression.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of disengagement coping on the relationship between stigma and anxiety.

A similar pattern for was observed when anxiety was the psychological outcome. More anxiety was predicted when disengagement coping was high, as concern with public attitudes or negative self-image increased. When disengagement coping was low, reported changes in these particular stigma experiences did not affect predicted anxiety (Table 3). Although the interaction between enacted stigma and disengagement coping predicting anxiety was only marginally significant, we chose to examine the simple slopes to see if the same pattern would emerge, which it did. Predicted anxiety increased as reports of enacted stigma increased when disengagement coping was high compared to when disengagement coping was low. Interestingly, a slightly different pattern emerged for disclosure concerns, disengagement coping, and anxiety. When disengagement coping was high, as disclosure concerns increased so did predicted anxiety. But when disengagement coping was low, increased disclosure concerns predicted decreased anxiety.

Engagement Coping, HIV/AIDS Stigma, and Psychological Well-being

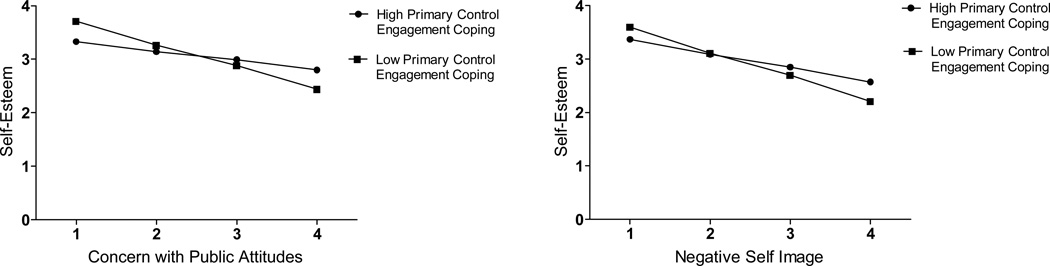

We also hypothesized that people who used primary control engagement coping (e.g., problem solving) or secondary control engagement coping (e.g., cognitive restructuring) to deal with the stress of HIV/AIDS stigma would report less depression, less anxiety, and more self-esteem, even as their stigma increased. These regression models are summarized in Table 4. Interactions between primary control engagement coping and two of the felt stigma measures, concern with public attitudes and negative self-image, significantly predicted self-esteem.

Table 4.

Summary of Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regression Analyses Psychological Well-Being Predicting from Engagement Coping and Stigma

| Depression | Anxiety | Self-Esteem | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Control Engagement Coping |

Secondary Control Engagement Coping |

Primary Control Engagement Coping |

Secondary Control Engagement Coping |

Primary Control Engagement Coping |

Secondary Control Engagement Coping |

|||||||

| ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | |

| Enacted | ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .07** | .05** | .05** | .06** | .06** | ||||||

| Sex (female) | .16** | .17* | .12 | .12 | −.01 | −.04 | ||||||

| Age | −.10 | −.08 | −.12 | −.11 | .23** | .22** | ||||||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.14* | −.13* | −.13 | −.12 | .01 | .01 | ||||||

| Step 2 | .16*** | .11*** | .11*** | .10*** | .10*** | .13*** | ||||||

| Coping | .06 | −.01 | .08 | .01 | .03 | .18** | ||||||

| Stigma | .32** | .33*** | .31*** | .32*** | −.32*** | −.30*** | ||||||

| Step 3 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | ||||||

| Interaction | −.06 | −.06 | .02 | −.04 | .05 | .11 | ||||||

| Total R2 | .19*** | .18*** | .16*** | .16*** | .16*** | .20*** | ||||||

| Concern with Public Attitudes | ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .07** | .05** | .05** | .06** | .06** | ||||||

| Sex (female) | .11 | .12 | .08 | .08 | .02 | .01 | ||||||

| Age | −.06 | −.05 | −.09 | −.08 | .19** | .18** | ||||||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.10 | −.10 | −.09 | −.08 | −.01 | −.02 | ||||||

| Step 2 | .22*** | .21*** | .16*** | .15*** | .11*** | .15*** | ||||||

| Coping | .09 | .01 | .12 | .01 | .01 | .12 | ||||||

| Stigma | .46** | .47*** | .39*** | .40*** | −.32*** | −.34*** | ||||||

| Step 3 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02* | .06*** | ||||||

| Interaction | −.01 | −.04 | .03 | .00 | .15* | .26*** | ||||||

| Total R2 | .28*** | .28*** | .22*** | .20*** | .19*** | .27*** | ||||||

| Negative Self-Image | ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .07** | .05** | .05** | .06** | .06** | ||||||

| Sex (female) | .14* | .14* | .10 | .10 | .00 | .00 | ||||||

| Age | −.02 | −.01 | −.04 | −.03 | .15* | .14* | ||||||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.03 | −.01 | −.02 | −.00 | −.10 | −.10 | ||||||

| Step 2 | .22*** | .21*** | .20*** | .18*** | .23*** | .25*** | ||||||

| Coping | .11 | .05 | .14* | .06 | .01 | .09 | ||||||

| Stigma | .48** | .48*** | .45*** | .45*** | −.50*** | −.47*** | ||||||

| Step 3 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .02* | .04*** | ||||||

| Interaction | −.03 | −.07 | .00 | −.03 | .14* | .20*** | ||||||

| Total R2 | .29*** | .28*** | .25*** | .24*** | .30*** | .34*** | ||||||

| Disclosure Concerns | ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | .07** | .07** | .05** | .05** | .06** | .06** | ||||||

| Sex (female) | .16* | .18** | .12 | .14 | −.02 | −.04 | ||||||

| Age | −.07 | −.06 | −.09 | −.08 | .21** | .20** | ||||||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −.11 | .09 | −.10 | −.08 | −.01 | −.02 | ||||||

| Step 2 | .07** | .04** | .06** | .03* | .02 | .06** | ||||||

| Coping | .17* | −.03 | .18** | −.01 | −.05 | .20** | ||||||

| Stigma | .24** | .19** | .22** | .17* | −.16* | −.11 | ||||||

| Step 3 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .03** | ||||||

| Interaction | −.07 | −.12 | −.05 | −.07 | .09 | .18** | ||||||

| Total R2 | .14*** | .12*** | .12*** | .09** | .09** | |||||||

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

We again examined the simple slopes of the significant interactions using the methodology described above (Aiken & West, 1991; Hayes & Matthes, 2009). The results of these analyses are reported in Table 3. Both increases in concern with public attitudes and in negative self-image predicted decreases in self-esteem at both high and low levels of primary control engagement coping (though this finding was marginally significant for high levels of primary control engagement coping and concern with public attitudes, p = .06, see Table 3). However, the slopes for concern with public attitudes and negative self-image were less steep when primary control engagement coping was high than when it was low. This pattern is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of primary control engagement coping on the relationship between self-esteem and two aspects of felt stigma: negative self-image and concern with public attitudes.

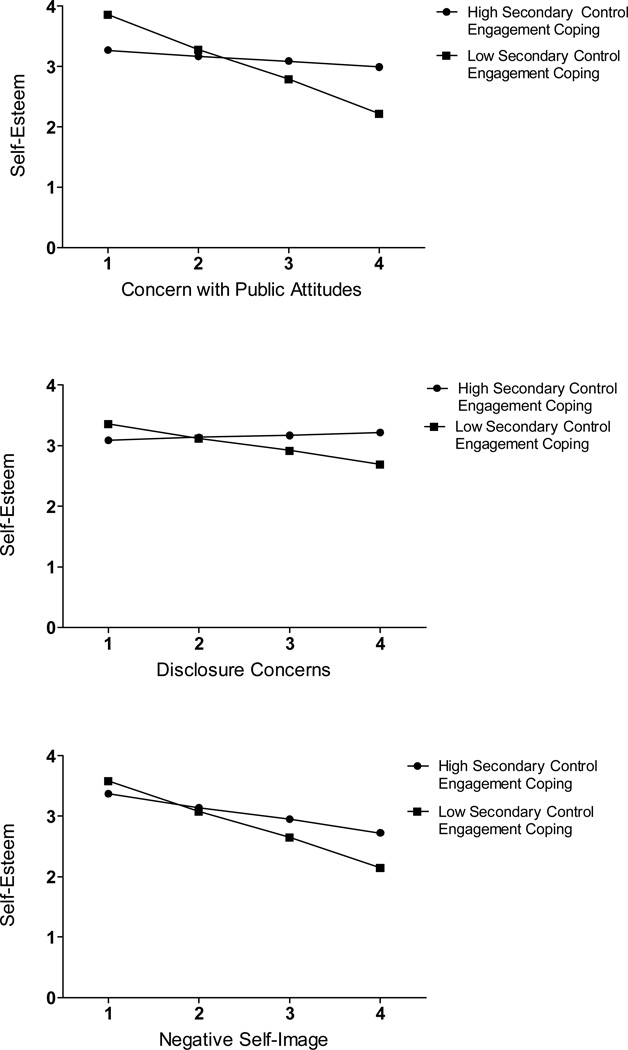

All of the interactions between the felt stigma subscales (but not enacted stigma) and secondary control engagement coping significantly predicted self-esteem (see Table 4). Examination of the simple slopes (reported in Table 3) showed that when secondary control engagement was high, neither increases in concern with public attitudes nor increases in disclosure concerns predicted changes in self-esteem. When secondary control engagement coping was low, both increases in concern with public attitudes and increases in disclosure concerns significantly predicted decreases in self-esteem. Increases in negative self-image significantly predicted lower self-esteem at both high and low levels of secondary control engagement coping. Similar to the pattern observed for primary control engagement coping, the slope for negative self-image was less steep when secondary control engagement coping was high. Figure 4 illustrates the pattern of the moderating effect of secondary control engagement coping on the relationship between each of the three felt stigma subscales and self-esteem.

Figure 4.

The moderating effect of secondary control engagement coping on the relationship between felt stigma and self-esteem

None of the interactions between any of the stigma subscales with either type of engagement coping predicted anxiety or depression (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study illustrates the importance of individual differences in coping strategies on the relationship between perceived stigma and psychological well-being. The way in which people coped with felt stigma was associated with mental health. People with HIV/AIDS who used relatively more disengagement coping and who reported more experiences of felt stigma had greater anxiety and depression compared to those who used relatively less disengagement coping. Moreover, this pattern was demonstrated for all forms of felt stigma (concern with public attitudes, negative self-image, and disclosure concerns), suggesting that using disengagement coping to deal with the anticipation and internalization of stigma may negatively impact psychological well-being. In contrast, the data suggests a trend that using disengagement coping to deal with high levels of enacted stigma is associated with greater anxiety, but not with greater depression. Participants generally indicated that they experienced more felt than enacted stigma. It may be that because experiences of enacted stigma are relatively uncommon, such experiences are not a major contributor to depressive symptoms. However, no matter how uncommon they are direct experiences with discrimination and exclusion may be sufficient to provoke fear and anxiety, particularly if the individual seeks to cope with such experiences by disengaging from them.

Our findings also suggest that the negative effects of felt stigma on self-esteem may be averted by using more secondary control engagement coping. Using the emotion regulation skills characteristic of secondary control engagement coping appears to serve as a protective factor against blows to self-esteem that otherwise are observed among people with HIV/AIDS who are worried about public opinion about people with HIV/AIDS (concern with public attitudes subscale) and from being worried about the consequences of others finding out about one’s HIV/AIDS status (disclosure concerns). Secondary control engagement coping also appeared to attenuate, though not eliminate, the association of negative self-image related to HIV/AIDS on overall self-esteem. Likewise, using more primary control engagement coping to deal with stress associated with public attitude concerns and negative self-image predicted a slower decrease in self-esteem compared to those using less primary control engagement coping.

What secondary control and primary control engagement coping have in common is that they both involve engaging rather than disengaging with the stressor. It is noteworthy, therefore, that both forms of engagement coping moderated the relationship of felt stigma on self-esteem. These findings are consistent with theoretical approaches (e.g., (Crocker & Major, 1989) which suggest that the self-esteem of stigmatized people is resilient to the threat posed by stigmatization because of the coping efforts stigmatized people make (e.g., by blaming poor outcomes on being stigmatized, not to personal shortcomings). Our findings add to this theorizing by suggesting that a broad array of engagement coping strategies (as captured by the coping measure we used) may ameliorate the effects of stigmatization on self-esteem. In other words, stigmatized people may cope with stigma in much the same way that people cope with anything else – and our results suggest that such efforts may successfully buffer the effects of stigma on self-esteem.

Another important aspect of these findings is that disengagement coping primarily moderated the relationship of stigma to depression and anxiety, whereas engagement coping primarily moderated the association of stigma to self-esteem. In particular, disengagement coping did not moderate the relationship of HIV/AIDS stigma and self-esteem, whereas as we just discussed, secondary and primary engagement coping did moderate these relationships. In addition, as we described above, disengagement coping did moderate the association of felt stigma and anxiety and depression, but engagement coping (primary or secondary) to cope with HIV/AIDS stigma did not. In contrast to previous research on stress related to HIV/AIDS and psychological well-being, our results support a view that using different coping styles to deal with stigma may impact different aspects of psychological health rather than have an overarching effect on all facets of psychological well-being.

For example, our findings suggest that, like other HIV-related stressors, using disengagement coping to manage the stress related to HIV/AIDS stigma is associated with increased symptoms of depression and anxiety (Gonzalez, et al., 2010; Heckman, et al., 2004; Turner-Cobb, et al., 2002). However, using engagement coping to deal with the stress of HIV/AIDS stigma did not predict a reduction in these same symptoms as has been reported in other research (for example, (Pakenham & Rinaldis, 2001), though it did appear to protect self-esteem in a way that mimics the positive effect of engagement coping on life satisfaction (Heckman, 2003). Psychological health is composed of a constellation of factors that include both the absence of negative symptoms (e.g., depression) and the presence of positive psychological functioning (e.g., self-esteem). When stressors threaten psychological health they may impact different aspects of mental health. As a result, different coping strategies used to deal with these stressors may have varying effects on psychological health. Some coping strategies, like engagement coping, may be more appropriate for enhancing positive functioning, while others, like disengagement coping, may increase some forms of psychological maladjustment. Our findings show that this may be particularly true when coping with stigma as opposed to more general sources of stress.

Consistent with this conclusion, Heckman and Carlson (2007) recently reported their findings from a telephone-administered intervention aimed at improving the quality of life of people with HIV living in rural areas by teaching participants how to use more problem and emotion focused coping skills (similar to primary and secondary control engagement coping). Unfortunately, symptoms of depression among participants who learned these skills did not differ from participants in control conditions. Our findings suggest that making changes to problem or emotion focused coping may not have an impact on symptoms such as depression, but could have protected self-esteem, which was not assessed in the Heckman and Carlson (2007) intervention.

Future interventions should consider that not all coping strategies will have the same impact on all aspects of psychological well-being, and the type of coping strategy taught may need to be tailored to address specific aspects of well-being. In addition, treatment plans may also benefit from including an assessment of enacted and felt stigma to provide additional information as to why a client with HIV/AIDS may be experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and/or a decrease in self-esteem. Ross, Doctor, Dimito, Kuehl, and Armstrong (2007) demonstrated that a traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) model that included sessions that focused specifically on processing the stigma and oppression experienced by their lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered clients had a positive effect on depression and self-esteem, both in the short term (immediately after therapy) and in the long-term (at a two-month follow up). A similar adaptation could be proposed for people living with HIV/AIDS to help them to process their experiences and anticipation of HIV/AIDS stigma.

Although our research suggests that coping with HIV/AIDS stigma may enhance or diminish psychological well-being, it is important to note that our data are correlational. It is possible that experiencing anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem affects how people cope with HIV/AIDS stigma, and may also affect the extent to which individuals perceive felt and enacted HIV/AIDS stigma. We are currently engaged in longitudinal research to explore the direction of the relationship between these variables.

Another caveat involves the different recall periods used for our dependent variables and our independent variables. The SCL-90 directs participants to use a specific recall period (7 days including the day of assessment) when reporting their experiences with anxiety and depression, and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale was phrased in the present tense, guiding participants to report their current state of being. However, the HIV/AIDS Stigma Scale referred both to past experiences (e.g., I have lost friends by telling them that I have HIV/AIDS.) and present concerns (e.g., I worry people I who know I have HIV/AIDS will tell others.). Also, the Response to Stress Questionnaire-HIV/AIDS had an undefined recall period, instead directing participants to focus on how they cope with stigma by instructing them to think of stigma events, which may have happened in the past or present. One concern would be that the bulk of stigmatizing events or concerns, and efforts to cope with them, may have occurred during the early days of navigating a new HIV or AIDS diagnosis and do not accurately reflect what is happening in the present. This prompted us to include time since diagnosis in our regression analyses as a control variable when examining the relationship between stigma, coping with stigma, and psychological well-being. Finding the relationships we did between stigma, coping with stigma, and psychological well-being after controlling for the passage of time may suggest that even if the stigma and the coping strategies used to deal with stigma may not be current they have a far reaching effect on current psychological well-being.

Additionally, our sample was limited to a more rural area of New England (mainly, Vermont). It may be that the experiences of people living with HIV/AIDS in more urban areas or areas where there are larger numbers of people living with HIV/AIDS are different (i.e., perhaps they experience more enacted stigma, or live in areas where they are less concerned with people discovering their HIV status). As a result, the impact of coping with HIV/AIDS stigma may influence psychological well-being differently. Replicating this study in more urban areas, as well as in areas where there are higher concentrations of people living with HIV/AIDS in one community is warranted before more general implications can be made.

In summary, this study shows that the particular coping strategies people with HIV/AIDS use to cope with their stigmatized status are related in different ways to psychological outcomes including anxiety, depression, and self-esteem. These relationships suggest that efforts to teach people with HIV/AIDS strategies to deal with HIV/AIDS stigma by using fewer disengagement coping strategies and more engagement coping strategies may improve the overall psychological well-being of people with HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grant “Rural Ecology and Coping with HIV Stigma” RO1 MH 066848 obtained by Sondra E. Solomon, Ph.D. and Carol T. Miller, Ph.D.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV Stigma Scale. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among Human Immunodeficiency Virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn JY, Solomon SE, Miller C, Forehand R. Measurement of stigma in people with HIV/AIDS: A reexamination of the HIV stigma scale. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19(3):198–208. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro KG, Ward JW, Slutsker L, Buehler JW, Jaffe HW, Berkelman RL. 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Gibson DR, Chitwood DD, Coates TJ. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(3):339–362. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. A meta-analysis of risk for Major Depressive Disorder among HIV-positive individuals. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:725–730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Osowiecki D, Welch A. Effortful and involuntary responses to stress: Implications for coping with chronic stress. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Coping With Chronic Stress. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 105–130. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(1):87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;66(6):976–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Passin WF, Herbst JH, Rama SM, Malow RM, Purcell DW, et al. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions on HIV-positive persons' mental health and immune functioning. Health Psychology. 2008;27:4–14. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96(4):608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social Stigma. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th ed. Vol. 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Symptom Checklist-90-R. Minneapolis: Pearson Education, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA. Experiences of stigma in older adults living with HIV/AIDS: A mixed-methods analysis. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21:740–752. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler NS, Denisoff E, Rutherford A. Anxiety and depression: Evidence for the differentiation of commonly cooccurring constructs. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1998;20:149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fife BL, Wright ER. The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 2000;41:50–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Solomon SE, Zvolensky MJ, Miller CT. Exploration of the Relevance of Anxiety Sensitivity among Adults Living with HIV/AIDS for Understanding Anxiety Vulnerability. Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15(1):138–146. doi: 10.1177/1359105309344898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavioral Research Methods. 2009;41(3):924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman TG. The chronic illness quality of life (CIQOL) model: Explaining life satisfaction in people living with HIV disease. Health Psychology. 2003;22:140–147. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman TG, Anderson ES, Sikkema KJ, Kochman A, Kalichman SC, Anderson T. Emotional Distress in Nonmetropolitan Persons Living With HIV Disease Enrolled in a Telephone-Delivered, Coping Improvement Group Intervention. Health Psychology. 2004;23(1):94–100. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman TG, Carlson BC. A randomized clinical trial of two telephone-delivered, mental health interventions for HIV-infected persons in rural areas of the United States. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: Prevalence and trends 1991–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2002 Mar;Vol 92(3):371–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.371. 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis BG. MediaLab [Computer software] (Version v2004) New York: Empirisoft Corporation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Bahr R, Kalichman SC, Morgan MG, Stevenson LY, et al. Outcome of Cognitive-Behavioral and Support Group Brief Therapies for Depressed, HIV-Infected Persons. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1679–1686. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.11.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kylma J, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K, Lahdevirta J. Hope, despair and hopelessness in living with HIV/AIDS: a grounded theory study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;33:764–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawless S, Kippax S, Crawford J. Dirty, diseased and undeserving: The positioning of HIV positive women. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43(9):1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie C, Gadalla TM. Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):742–753. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Quinton W, McCoy S. Antecedents and consequences of attributions to discrimination: Theoretical and empirical advances. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 34. New York: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 251–329. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003 Sep;Vol 129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Kaiser CR. A theoretical perspective on coping with stigma. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57(1):73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Major B. Coping with stigma and prejudice. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck R, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The Social Psychology of Stigma. New York: The Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 243–272. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Have TT, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Dadds RM, Terry DJ. Relationship between adjustment to HIV and both social support and coing strategies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(6):1194–1203. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.6.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Dadds RM, Terry DJ. Adaptive demands along the HIV disease continuum. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;42:245–256. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Rinaldis M. The role of illness, resources, appraisal, and coping strategies in adjustment to HIV/AIDS: The direct and buffering effects. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001 Jun;Vol 24(3):259–279. doi: 10.1023/a:1010718823753. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Rinaldis M. Development of the HIV/AIDS Stress Scale. Psychology & Health. 2002;17(2):203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Pinel EC. Stigma-consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(1):114–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image (Rev. ed.) Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ross LE, Doctor F, Dimito A, Kuehl D, Armstrong SM. Can talking about oppression reduce depression? Modified CBT group treatment for LGBT people with depression. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services:Issues in Practice, Policy, and Research. 2007;19:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Scambler G. Stigma and disease. The Lancet. 1998;352:1054–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Fielder R. Stress management intervention for HIV+ adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, 1989 to 2006. Health Psychology. 2008;27:129–139. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Cohen LL, Hyers LL. Experiencing everyday prejudice and discrimination. In: Swim JK, Stangor C, editors. Prejudice: The targets' perspective. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman GL, Angelino AF. The psychiatry of AIDS: A guide to diagnosis and treatment. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Cobb JM, Gore-Felton C, Marouf F, Koopman C, Kim P, Israelski D, et al. Coping, social suport, and attachment style as psychosocial correlatates of adjustment in men and women with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;25:337–353. doi: 10.1023/a:1015814431481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on heath behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(5):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam PK, Templin T, Frey M. Stigma scale revised: Reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV+ youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]