Abstract

Molecular detection of minimal residual disease (MRD) has become established to assess remission status and guide therapy in patients with ProMyelocytic Leukemia–RARA+ acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). However, there are few data on tracking disease response in patients with rarer retinoid resistant subtypes of APL, characterized by PLZF–RARA and STAT5b–RARA. Despite their rarity (<1% of APL) we identified 6 cases (PLZF–RARA, n = 5; STAT5b–RARA, n = 1), established the respective breakpoint junction regions and designed reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assays to detect leukemic transcripts. The relative level of fusion gene expression in diagnostic samples was comparable to that observed in t(15;17) – associated APL, affording assay sensitivities of ∼1 in 104−105. Serial samples were available from two PLZF–RARA APL patients. One showed persistent polymerase chain reaction positivity, predicting subsequent relapse, and remains in CR2, ∼11 years post-autograft. The other, achieved molecular remission (CRm) with combination chemotherapy, remaining in CR1 at 6 years. The STAT5b–RARA patient failed to achieve CRm following frontline combination chemotherapy and ultimately proceeded to allogeneic transplant on the basis of a steadily rising fusion transcript level. These data highlight the potential of RT-qPCR detection of MRD to facilitate development of more individualized approaches to the management of rarer molecularly defined subsets of acute leukemia.

Keywords: minimal residual disease, acute myeloid leukemia

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is characterized by rearrangements of the gene encoding retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα), which is most commonly fused to the ProMyelocytic Leukemia (PML) gene consequent upon the t(15;17)(q22;21) (reviewed Mistry et al., 2003). In approximately 10% of APL cases the t(15;17) is not detected, due to cytogenetic failures, simple variant translocations involving 15q22 or 17q21 and another partner chromosome, or more complex rearrangements (Grimwade et al., 2000). The majority of these cases lacking the classic t(15;17) nevertheless still harbor an underlying PML–RARA fusion gene, while in ∼1–2% of cases presenting with APL an alternative fusion partner is involved (Grimwade et al., 2000). These include PLZF (ZBTB16), NPM1, NuMA, FIP1L1, and BCOR, formed as a result of the t(11;17)(q23;q21), t(5;17)(q35;q21), t(11;17)(q13;q21), t(4;17)(q12;q21), and t(X;17)(p11;q21), respectively; while the PRKAR1A, and STAT5b genes are fused to RARA following rearrangements involving 17q (Chen et al., 1993; Redner et al., 1996; Wells et al., 1997; Arnould et al., 1999; Catalano et al., 2007; Kondo et al., 2008; Yamamoto et al., 2010). The nature of the fusion partner has an important bearing on disease biology, particularly the likely response to molecularly targeted therapies in the form of all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide (ATO). ATRA sensitivity has been documented in APL subtypes involving PML, NPM1, NuMA, and FIP1L1 (reviewed Grimwade et al., 2010); whereas, PLZF–RARα and STAT5b–RARα have both been associated with primary resistance to retinoids and a poorer prognosis (Licht et al., 1995; Arnould et al., 1999; Dong and Tweardy, 2002). In the case of PLZF–RARα associated APL with the t(11;17)(q23;q21), the retinoid insensitivity is compounded by expression of the reciprocal RARα–PLZF fusion product from the derivative chromosome 17 [der(17)], which functions as a transcriptional activator targeting PLZF-binding sites leading to upregulation of cellular retinoic acid binding protein I (CRABP1), which sequesters retinoic acid, limiting its access to the nucleus (Guidez et al., 2007). To date, sensitivity to arsenic has only been demonstrated in PML–RARα positive APL, reflecting the capacity of ATO to bind directly to the PML moiety of the fusion protein inducing its degradation via the proteosome (Zhang et al., 2010).

Molecular diagnostics to establish the nature of the fusion partner are therefore important for appropriate management, but in addition the application of sensitive minimal residual disease (MRD) assays to track treatment response has been found to be clinically useful in patients with PML–RARα+ disease, with previous studies showing that achievement of molecular remission (CRm) as determined by qualitative or quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays (with a sensitivity of 10–4) is a prerequisite for long-term remission and disease cure (reviewed Sanz et al., 2009; Grimwade and Tallman, 2011). These assays when applied at the post-consolidation timepoint are not sufficiently sensitive to identify all patients destined to relapse (Grimwade et al., 1996; Burnett et al., 1999). However, sequential molecular monitoring studies have shown that in patients who achieve CRm, recurrence of PCR positivity heralds disease relapse (Diverio et al., 1998; Jurcic et al., 2001). Prediction is further refined by the use of reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) which enables parallel quantification of endogenous control genes (e.g., Abelson, ABL) and leukemic transcripts, such that poor quality samples that could otherwise give rise to “false negative” results can be more reliably identified (Grimwade et al., 2009). Importantly, it also provides data on the kinetics of disease relapse, informing development of optimized MRD monitoring schedules (reviewed Freeman et al., 2008).

A significant complication of relapsed APL is death from hemorrhage due to the associated coagulopathy (Sanz et al., 2009). Therefore, Italian GIMEMA and Spanish PETHEMA groups explored the use of serial MRD monitoring as a tool to identify patients with impending relapse of APL (based upon persistent PCR positivity during therapy or recurrent PCR positivity in patients showing an initial response) to guide pre-emptive therapy to prevent disease progression (Lo Coco et al., 1999; Esteve et al., 2007). These studies, which were conducted before the availability of ATO for the treatment of relapse, suggested a survival benefit for early treatment intervention. More recently, we have shown in the Medical Research Council (MRC) AML15 trial that sequential monitoring using standardized RT-qPCR assays [developed within the Europe Against Cancer (EAC) program; Gabert et al., 2003)] provides the most powerful independent prognostic factor in APL (Grimwade et al., 2009). In addition we clearly demonstrated that these assays could be used to pinpoint particular patients destined to relapse, allowing successful delivery of pre-emptive therapy (Grimwade et al., 2009). This led to a significant reduction in the rate of frank relapse and improved survival, which was most marked in patients with high risk disease, i.e., with presenting white blood cell count above 10 × 109/l. Moreover, we have shown that use of MRD monitoring to allow early deployment of ATO is associated with a significant reduction in treatment-related complications – substantially decreasing the risk of hyperleukocytosis and the associated life-threatening differentiation syndrome (Grimwade et al., 2009). Accordingly molecular monitoring of MRD has become widely recognized as a standard component of care for patients with PML–RARA+ APL, as reflected in recent disease guidelines (Sanz et al., 2009).

While treatment is increasingly being tailored to the needs of individual patients, there are virtually no data on molecular monitoring in PLZF–RARα and STAT5b–RARα associated APL, which have been associated with a poorer prognosis. We have developed sensitive RT-qPCR assays suitable for tracking treatment response in these patients and which could be used to assess novel therapeutic approaches in retinoid insensitive disease.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Our laboratory has served as the reference center for molecular diagnosis of APL for successive MRC/National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) trials since 1994 and also receives samples for diagnosis and MRD monitoring from non-trial patients from across the UK (Burnett et al., 1999; Grimwade et al., 2009). To date, we have identified six cases of morphologically suspected APL presenting in the UK that lacked the t(15;17) and were subsequently found to have an underlying PLZF–RARA (n = 5) or STAT5b–RARA (n = 1) fusion (Table 1). These include a previously unreported case (UPN 5) with the t(11;17)(q23;q21) giving rise to the PLZF–RARA fusion, treated within the UK MRC AML12 trial. Clinical details of the APL patient with the STAT5b–RARα fusion, who presented with pancytopenia and intracardiac thrombus have recently been described (Cahill et al., 2011). Samples were taken for molecular analysis following informed patient consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was subject to Local Research Ethics Committee approval (St Thomas’ Hospital Research Ethics Committee ref 06/Q0702/140).

Table 1.

Clinical details and disease characteristics of patients with PLZF–RARA or STAT5b–RARA associated APL.

| Patient | Age at diagnosis (years) | Presenting WBC (109/l) | Cytogenetics | Fusion genes expressed | Treatment | Outcome | RQ-PCR assay sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPN1 | 53 | 4.5 | 46,XY,t(11;17)(q23;q21) | PLZF–RARA (2ZF) RARA–PLZF | ADE/G-CSF/ATRA, 3 consolidation courses MRC AML12* | Relapse at 45mo, FLAGx2 + ATRA, Cy TBI autograft. Alive in second CR at 177mo from diagnosis | 1 in 105.1 (PLZF–RARA), 1 in 104.3 (RARA–PLZF) |

| UPN2 | 50 | 6.8 | 46,XY,t(11;17)(q23;q21)/45,X–Y,t(11;17)(q23;q21) | PLZF–RARA (2ZF) | ADE/ATRA, ADE MACE, MiDAC | 1st CR 73mo from diagnosis | 1 in 104.3 |

| UPN3 | 75 | 2.0 | 46,XY,t(11;17)(q23;q21)/46,idem,del(12)(p1?)/46,idem,−6,+r | PLZF–RARA (3ZF) RARA–PLZF | DAT2 + 7/ATRA, DAT2 + 7, MACE | Relapse at 55mo, Dauno + Ara-C. Died in second CR 88mo from diagnosis | 1 in 104.3 (PLZF–RARA), 1 in 104.3 (RARA–PLZF) |

| UPN4 | 58 | 7.4 | 46,XY,t(7;17)(q36;q21) | PLZF–RARA (3ZF) | DAT3 + 10/ATRA, DAT3 + 8/ATRA, MACE | Died in relapse 3.5mo from diagnosis | 1 in 104.6 |

| UPN5 | 62 | 1.2 | 47,XY,+8[3]/47,XY,+8,t(11;17)(q23;q21)[23] | PLZF–RARA (3ZF) RARA–PLZF | MRC AML12 | Relapsed at 7mo. Died in relapse at 15mo | 1 in 104.6 (PLZF–RARA), 1 in 104.6 (RARA–PLZF) |

| UPN6 | 29 | 5.6 | 46,XX,t(3;17)(q26;q21) | STAT5b–RARA | AIDA #1, DA 3 + 8, Ara-C 1.5g/m2 × 2 | Persistent PCR positivity → FLA, BuCy sibling allograft. Died 15mo from diagnosis – respiratory failure | 1 in 105.4 |

UPN5 is a previously unreported case. Clinical details and information regarding further molecular characterization of UPNs1–4 has been reported elsewhere (Culligan et al., 1998; Grimwade et al., 1997; Grimwade et al., 2000; Guidez et al., 2007). Details of the clinical presentation of the STAT5b–RARA case (UPN6) have been described previously (Cahill et al., 2011). *Details of the MRC AML12 protocol have been published previously (Burnett et al., 1999). Dauno, daunorubicin; Ara-C, cytosine arabinoside.

Characterization of APL fusion partner

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Ltd., UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and 2 μg were used for cDNA synthesis with random hexamers (Invitrogen Ltd., UK) and either M-MLV or SuperScript II reverse transcriptases (both Invitrogen Ltd., UK). In four cases with documented t(11;17)(q23;q21) on diagnostic cytogenetic assessment, diagnostic samples were screened for expression of PLZF–RARA and reciprocal RARA–PLZF fusion transcripts by nested RT-PCR, as previously described (Grimwade et al., 1997). In 2 patients with simple variant translocations, i.e., t(7;17)(q36;q21) and t(3;17)(q26;q21) in UPN4 and UPN6, respectively, 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) PCR was performed to identify the RARA fusion partner, using 2 μg of total RNA and the 5′/3′ RACE Kit, second generation (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using an antisense gene-specific primer located in RARA exon 4 (SP1, 5′-CGGTGACACGTGTACACCATGTTC-3′) and the homopolymeric A-tail was added to its 3′ end as per manufacturer’s instructions. Tailed cDNA was then amplified by PCR using a second gene-specific primer located in RARA exon 4 upstream of the SP1 primer (SP2, 5′-TGGATGCTGCGGCGGAAGAAGC-3′), and the supplied Oligo dT-anchor primer (5′-GACCACGCGTATCGATGTCGAC(T)16V-3′, where V = A, C or G) which binds to the 5′ end of the poly(A)-tail. First round PCR product was then used as a template in a second PCR reaction with a nested PCR primer (SP3, 5′-CCATAGTGGTAGCCTGAGGACTTG-3′) located in RARA exon 3 and the PCR anchor primer (5′-GACCACGCGTATCGATGTCGAC-3′) from the kit which anneals to the sequence introduced by the non-T portion of the Oligo d(T)-anchor primer in the previous PCR round. Upon visualization in 1% agarose gels, purified 5′ RACE PCR products were cloned using the pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega, UK) and identified by sequence analysis (Figure 1). Breakpoint location was further verified by sequencing of nested RT-PCR products which were obtained from independent RNA aliquots.

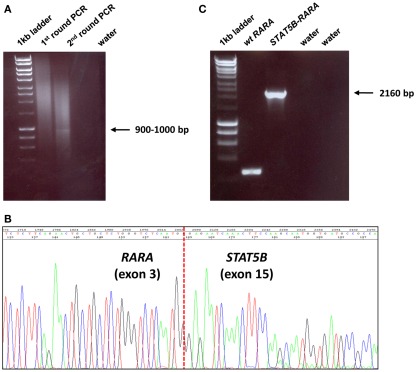

Figure 1.

Identification of STAT5b–RARA fusion underlying APL in UPN6 with t(3;17)(q26;q21) variant translocation. (A) 5′ RACE was undertaken, which showed a weak band on second round PCR; the amplification product was cloned, sequenced and found to be a fusion between STAT5b exon 15 and RARA exon 3 (B), in accordance with the breakpoints identified in 4 previously reported cases with this rearrangement (Arnould et al., 1999; Kusakabe et al., 2008; Iwanaga et al., 2009; Qiao et al., 2011). Detection of STAT5b–RARA fusion transcripts was confirmed by nested RT-PCR using a fresh aliquot of RNA (C).

Development of RT-qPCR assays for APL fusion transcripts

The assay designs to amplify PLZF–RARA and STAT5b–RARA fusion transcripts were adapted from the standardized PML–RARA assay developed in the EAC program (Gabert et al., 2003), using the EAC probe and reverse primer located in RARA exon 3 in conjunction with newly designed forward primers located within PLZF (exon 3 or 4, depending upon the breakpoint) and STAT5b (exon 15), respectively (Figure 2; Table 2). In addition, reciprocal RARA–PLZF transcripts expressed from the der(17) were detected using a common forward primer and probe located in RARA exon 2, which were previously described for amplification of reciprocal RARA–PML transcripts in APL with the classic t(15;17) (Grimwade et al., 2009), used in conjunction with newly designed reverse primers located in PLZF exons 4 and 5, according to patient breakpoint (Figure 2; Table 2). Assays were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). RT-qPCR reactions were run on the ABI7900 platform under the standard EAC conditions (Gabert et al., 2003), with expression of leukemic fusion transcripts normalized to the ABL control gene using the ΔCt method, as described previously (Flora and Grimwade, 2004; Grimwade et al., 2009). All assays were confirmed to be fusion transcript specific based on lack of detectable amplification in normal control (n = 5) or diagnostic PML–RARA+ APL (n = 5) blood and bone marrow (BM) samples. RT-qPCR assay sensitivity was calculated, based upon the level of expression of leukemic transcripts in the diagnostic sample in relation to the ABL control gene, as described (Freeman et al., 2008; Grimwade et al., 2009). Assays were run in triplicate; amplification in at least two of three replicates with Cycle Threshold (Ct) values ≤40 (threshold 0.05) was required to define a result as PCR positive for the fusion transcript in question, according to EAC criteria (Gabert et al., 2003). No-template controls (NTCs) for each assay were run in duplicate to exclude possible contamination, while patients’ diagnostic samples served as positive controls. MRD level in follow-up samples was calculated using the ΔΔCt method as described by Beillard et al. (2003). Briefly, the difference in expression between the fusion transcript (FT) and ABL in a follow-up (FUP) sample (ΔCtFUP = CtFT−CtABL) was normalized to the difference between their expression at diagnosis (Dx) (ΔCtDx = CtFT−CtABL) using the following formula: 10[(ΔCtFUP−ΔCtDx)/−3.5], where −3.5 represents the mean slope observed in the EAC program for plasmid standard curves (Beillard et al., 2003). Persistent PCR positivity was defined by the presence of leukemic transcripts throughout frontline therapy including the post-consolidation timepoint. CRm was defined as lack of detection of leukemic fusion transcripts in a BM sample affording a sensitivity of at least 1 in 104.

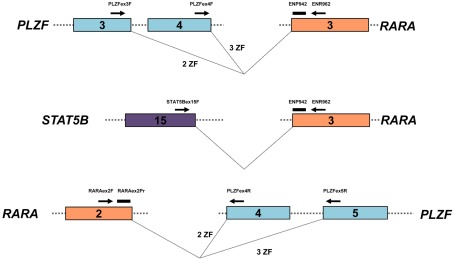

Figure 2.

Design of RT-qPCR assays to detect PLZF–RARA, RARA–PLZF, and STAT5b–RARA fusion transcripts. PLZF–RARA and STAT5b–RARA transcripts were detected with the common Europe Against Cancer probe (ENP942) and reverse primer (ENR962) located in RARA exon 3, used in conjunction with fusion-specific forward primers (see Table 2). For PLZF–RARA cases in which the chromosome 11 breakpoint fell within intron 3 of PLZF [retaining 2 zinc fingers (ZF) in the PLZF moiety of the resultant PLZF–RARα fusion protein] the forward primer was located in PLZF exon 3 (upper panel). Whereas for cases in which the breakpoint fell within intron 4 (retaining 3 ZF in the PLZF moiety of PLZF–RARα), the forward primer was located within exon 4 (upper panel). For amplification of STAT5b–RARA, the forward primer was placed in STAT5b exon 15 (middle panel). In UPN1, UPN3, and UPN5, reciprocal RARA–PLZF transcripts were co-expressed; RT-qPCR assays were designed for this target using a previously published common forward primer and probe located in RARA exon 2 (Grimwade et al., 2009), used in conjunction with a reverse primer located in PLZF exon 4 or 5, according to chromosome 11 breakpoint location (bottom panel).

Table 2.

Primers and probes used to detect APL fusion transcripts.

| Primer/probe | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| PLZF–RARA AND STAT5B–RARA | |

| PLZFex3F | TGGATAGTTTGCGGCTGAGA |

| PLZFex4F | GAGACACACAGGCAGACCCATA |

| STAT5Bex15F | GCATCACCATTGCTTGGAAG |

| ENR962* | GCTTGTAGATGCGGGGTAGAG |

| ENP942* | FAM–AGTGCCCAGCCCTCCCTCGC–TAMRA |

| RARA–PLZF | |

| RARAex2F‡ | CCCCTATGCTGGGTGGACT |

| PLZFex4R | CACCGCACTGATCACAGACAA |

| PLZFex5R | AGACAGAAGACGGCCATGTCA |

| RARAex2Pr‡ | FAM–CCGCCAGGCGCTCTGACCAC–TAMRA |

Results

Molecular characterization of APL cases with alternative fusion partners

Molecular analysis was undertaken in six cases of PML–RARA negative APL. In four cases (UPN1-3, UPN5), cytogenetics showed the t(11;17)(q23;q21), and presence of a PLZF/RARA rearrangement was confirmed by conventional nested RT-PCR (Table 1). In two cases (UPN4, UPN6) with t(7;17)(q36;q21) and t(3;17)(q26;q21) we postulated occurrence of a novel APL fusion; however, in both cases 5′ RACE revealed involvement of a known fusion partner, i.e., PLZF and STAT5b, respectively (Table 1; Figures 1 and 2), which was confirmed by nested RT-PCR performed on fresh aliquots of RNA from the diagnostic samples. In two cases with PLZF/RARA rearrangements, the chromosome 11 breakpoint fell within PLZF intron 3, leading to retention of 2 zinc fingers (2ZF) in the PLZF moiety of the PLZF–RARα fusion protein. In the other three patients, the PLZF breakpoint fell within intron 4, leading to inclusion of 3 zinc fingers (3ZF) in the PLZF component of PLZF–RARα (Table 1). Reciprocal RARA–PLZF fusion transcripts were co-expressed in three of five cases (Table 1). In UPN6 with the STAT5b–RARA fusion, the breakpoint location within the STAT5b locus was found to be identical to that reported previously (Arnould et al., 1999; Kusakabe et al., 2008; Iwanaga et al., 2009; Qiao et al., 2011; Figure 1). In accordance with the findings reported in the index case (Arnould et al., 1999), reciprocal RARA–STAT5b transcripts were not detected in UPN6.

Development of RT-qPCR assays to track treatment response in patients with PLZF–RARA and STAT5b–RARA associated APL

In order to detect PLZF–RARA and STAT5b–RARA transcripts by RT-qPCR, forward primers were designed to be used in conjunction with the common probe and reverse primer developed within the EAC program to amplify PML–RARA fusion transcripts (Figure 2; Gabert et al., 2003). To amplify reciprocal RARA–PLZF transcripts by RT-qPCR, reverse primers were designed within PLZF exon 4 or 5 (according to patient breakpoint location), used in conjunction with the common forward primer and probe both located within RARA exon 2 (Figure 2), which we have recently validated for amplification of reciprocal RARA–PML transcripts in patients with t(15;17) APL within the UK MRC AML15 trial (Grimwade et al., 2009). The relative expression of PLZF–RARA at diagnosis was comparable to that observed for PML–RARA transcripts in t(15;17) associated APL (Grimwade et al., 2009). The ΔCtDx ranged from −2 to +1, corresponding to assay sensitivities for detection of PLZF–RARA transcripts of between 1 in 104.3 and 1 in 105.1 (Table 1). In the three patients who were informative for the reciprocal RARA–PLZF assay, this was not found to improve the sensitivity to detect MRD as compared to detection of PLZF–RARA alone (Table 1). In UPN6, STAT5b–RARA transcripts were found to be very highly expressed at diagnosis (ΔCtDx = −3), affording an assay sensitivity of 1 in 105.4.

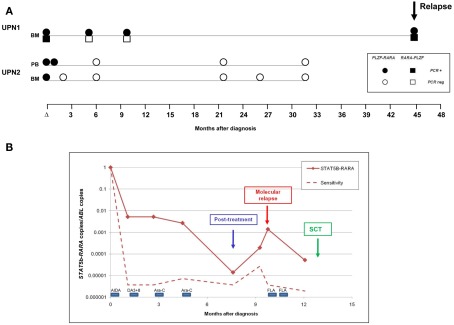

In two PLZF–RARA patients (UPN1, UPN2), follow-up samples were available for analysis. Samples from UPN1 had originally been tested by conventional nested RT-PCR, with BMs taken at 5 and 10 months from diagnosis found to test PCR negative. However, in accordance with our experience with PML–RARA+ APL, the RT-qPCR assay afforded greater sensitivity, with PLZF–RARA transcripts detected at both timepoints (Figure 3A). Reciprocal RARA–PLZF transcripts were not detectable in these follow-up samples in accordance with the poorer sensitivity afforded by this assay (Figure 3A; Table 1). Failure to achieve CRm following frontline therapy predicted subsequent disease relapse, which occurred at 45 months from original diagnosis (Figure 3A). In UPN2, MRD monitoring was undertaken by RT-qPCR in real time; in this case, CRm was achieved with combination chemotherapy, PLZF–RARA transcripts remained undetected in subsequent surveillance MRD samples and this patient is in ongoing remission of APL at 73 months (Figure 3A). UPN6 with STAT5b–RARA was also monitored by RT-qPCR in real time (Figure 3B); this patient exhibited a 2-log reduction in fusion transcripts (i.e., 10−2 MRD level) following AIDA induction (ATRA + idarubicin). However, treatment response was much poorer than typically seen in PML–RARA+ APL (Grimwade et al., 2009), with no significant further decline in fusion transcript level following two further courses of chemotherapy (DA3 + 8; cytarabine 1.5g/m2). A 2-log decline in fusion transcripts was documented following the fourth course of chemotherapy (cytarabine 1.5g/m2); however STAT5b–RARA transcripts remained detectable at the post-treatment timepoint and exhibited a steady rise of ∼2-logs over the following 2 months. The patient was deemed to be in molecular relapse and received further therapy (Fludarabine, cytarabine) which led to a further decline in fusion transcripts. However, the patient never achieved a CRm and therefore proceeded to a myeloablative sibling donor allogeneic transplant with busulphan and cyclophosphamide conditioning, which was unfortunately complicated by respiratory failure, leading to the patient’s demise while still in clinical remission.

Figure 3.

Detection of minimal residual disease (MRD) by RT-qPCR assay in PLZF–RARA and STAT5b–RARA associated APL. (A) Serial samples were available from two patients (UPN1, UPN2) with t(11;17)(q23;q21)-associated APL. In UPN1, PLZF–RARA transcripts were still detectable at the post-treatment timepoint, predicting subsequent disease relapse. Reciprocal RARA–PLZF were not detectable in early follow-up samples, consistent with the poorer sensitivity of this assay in this patient (see Table 1). UPN2, who was not informative for RARA–PLZF, achieved molecular remission following frontline therapy and remains in ongoing remission of their leukemia. (B) Serial monitoring of STAT5b–RARA transcripts normalized to the ABL control gene in UPN6. The patient failed to achieve molecular remission following frontline therapy and showed a rapidly rising fusion transcript level indicative of impending full blown relapse (labeled “molecular relapse”). The patient received two courses of Fludarabine and cytosine arabinoside (FLA) as pre-emptive therapy and then proceeded to a sibling myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT).

Discussion

Application of molecular monitoring by RT-qPCR to establish remission status and identify patients needing additional therapy to achieve disease cure is now firmly established as a key component of the management of patients with PML–RARA+ APL (Sanz et al., 2009). However, there remains considerable uncertainty regarding the clinical utility of MRD monitoring in other forms of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). While there is evidence that RT-qPCR can be used to predict disease relapse in patients with nucleophosmin (NPM1) mutant AML (Schnittger et al., 2009; Krönke et al., 2011) and core binding factor (CBF) leukemia (Corbacioglu et al., 2010; Ommen et al., 2010), there are very limited data in patients with other molecularly defined subsets of disease.

To date, over 100 balanced chromosomal rearrangements which are considered to be primary events in leukemogenesis have been cloned (Mitelman et al., 2011). The characterization of the resulting chimeric fusion genes is not only important to achieve a greater understanding of disease biology, but has concomitantly yielded an extensive array of leukemia-specific targets that can effectively be used to track MRD by RT-qPCR. A number of genes (e.g., MLL, RUNX1, RARA, NUP98) are recurrently involved, fused to a range of potential partner genes. Depending upon breakpoint location, this allows common primers and probes located in the exon immediately adjacent to the breakpoint to be used in conjunction with an appropriate partner-gene specific primer to amplify the leukemic fusion transcript. In APL, translocation breakpoints consistently involve RARA intron 2, meaning that for cases with alternative fusion partners (e.g., PLZF, STAT5b, as described here), it is possible to use partner-specific forward primers in conjunction with an extensively validated probe and reverse primer located in RARA exon 3, that were designed in the EAC program (Gabert et al., 2003). Based on the expression of the fusion gene transcripts relative to the validated endogenous control gene ABL in diagnostic samples, it was established that the sensitivity of the assays was comparable to those used in PML–RARA+ APL, capable of detecting MRD at a sensitivity of at least 1 in 104. Due to the rarity of PLZF–RARA-associated APL, experience of MRD detection in patients with this subset of leukemia is extremely limited (Cassinat et al., 2006); nevertheless, the significance of the MRD results seems to parallel those observed in patients with classic PML–RARA+ disease. In particular, CRm can be achieved with frontline therapy and is a prerequisite for disease cure.

As has been clearly demonstrated in PML–RARA+ APL, in order to reliably predict relapse it is important to adopt a sequential MRD monitoring approach (reviewed Grimwade and Tallman, 2011). This was applied in the patient with STAT5b–RARA+ APL, showing a failure to achieve CRm following intensive frontline therapy. Based upon the rising transcript level, further therapy was given to prevent impending relapse followed by a sibling allogeneic transplant. This approach was based on published data showing that patients with PML–RARA+ APL with persistent PCR positivity can potentially be salvaged by allogeneic transplant (Lo-Coco et al., 2003; Grimwade et al., 2009; Kishore et al., 2010). However, unfortunately there was an unsuccessful outcome in our patient with STAT5b–RARA due to transplant-related complications.

Therefore in conclusion, we have used 5′ RACE PCR to characterize simple variant translocations in APL, identifying cases involving the PLZF and STAT5b genes. Having defined breakpoint regions by sequence analysis, we adapted standardized RT-qPCR assays used for disease monitoring in patients with the classic t(15;17) in order to detect leukemic transcripts in these retinoid resistant subtypes of APL. As a consequence of the rarity of these disease entities, the number of cases analyzed was very small and study of further patients is merited to identify thresholds that may be useful to predict risk of relapse. Nevertheless, this study highlights the potential of RT-qPCR to guide management in patients with infrequent recurring translocations for which there is currently a paucity of robust prognostic information on which to base treatment decisions, particularly with respect to the role of allogeneic transplant in first remission.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Sarah Ryley, Anthony Moorman, and Kim Smith for cytogenetic data from UPN4, UPN5, and UPN6, respectively. We thank Susanna Akiki, Yashma Patel, Adele Timbs, and Anna Schuh for provision of diagnostic and follow-up samples for analysis, and Ciro Rinaldi and Robert Hills for clinical information. David Grimwade and Jelena V. Jovanovic gratefully acknowledge support from Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research (grants 0153, 04036), the European LeukemiaNet and the National Institute for Health Research for development and evaluation of MRD assays to predict outcome and guide treatment approach. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-0108-10093). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. In addition David Grimwade is grateful for research funding from the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Charity.

References

- Arnould C., Philippe C., Bourdon V., Grégoire M. J., Berger R., Jonveaux P. (1999). The signal transducer and activator of transcription STAT5b gene is a new partner of retinoic acid receptor alpha in acute promyelocytic-like leukaemia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1741–1749 10.1093/hmg/8.9.1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beillard E., Pallisgaard N., van der Velden V. H., Bi W., Dee R., van der Schoot E., Delabesse E., Macintyre E., Gottardi E., Saglio G., Watzinger F., Lion T., van Dongen J. J., Hokland P., Gabert J. (2003). Evaluation of candidate control genes for diagnosis and residual disease detection in leukemic patients using “real-time” quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR) – a Europe Against Cancer program. Leukemia 17, 2474–2486 10.1038/sj.leu.2403136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett A. K., Grimwade D., Solomon E., Wheatley K., Goldstone A. H. (1999). Presenting white blood cell count and kinetics of molecular remission predict prognosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid: result of the randomized MRC trial. Blood 93, 4131–4143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill T. J., Chowdhury O., Myerson S. G., Ormerod O., Herring N., Grimwade D., Littlewood T., Peniket A. (2011). Myocardial infarction with intracardiac thrombosis as the presentation of acute promyelocytic leukemia: diagnosis and follow-up by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 123, e370–e372 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassinat B., Guillemot I., Moluçon-Chabrot C., Zassadowski F., Fenaux P., Tournilhac O., Chomienne C. (2006). Favourable outcome in an APL patient with PLZF/RARalpha fusion gene: quantitative real-time RT-PCR confirms molecular response. Haematologica 91(Suppl.), ECR58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano A., Dawson M. A., Somana K., Opat S., Schwarer A., Campbell L. J., Iland H. (2007). The PRKAR1A gene is fused to RARA in a new variant acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 110, 4073–4076 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Brand N. J., Chen A., Chen S. J., Tong J. H., Wang Z. Y., Waxman S., Zelent A. (1993). Fusion between a novel Kruppel-like zinc finger gene and the retinoic acid receptor-alpha locus due to a variant t(11;17) translocation associated with acute promyelocytic leukaemia. EMBO J. 12, 1161–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbacioglu A., Scholl C., Schlenk R. F., Eiwen K., Du J., Bullinger L., Fröhling S., Reimer P., Rummel M., Derigs H. G., Nachbaur D., Krauter J., Ganser A., Döhner H., Döhner K. (2010). Prognostic impact of minimal residual disease in CBFB-MYH11-positive acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 3724–3729 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culligan D. J., Stevenson D., Chee Y. L., Grimwade D. (1998). Acute promyelocytic leukaemia with t(11;17)(q23;q12-21) and a good initial response to prolonged ATRA and combination chemotherapy. Br. J. Haematol. 100, 328–330 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diverio D., Rossi V., Avvisati G., De Santis S., Pistilli A., Pane F., Saglio G., Martinelli G., Petti M. C., Santoro A., Pelicci P. G., Mandelli F., Biondi A., Lo-Coco F. (1998). Early detection of relapse by prospective reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis of the PML/RARalpha fusion gene in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia enrolled in the GIMEMA-AIEOP multicenter “AIDA” trial. Blood 92, 784–789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S., Tweardy D. J. (2002). Interactions of STAT5b-RARalpha, a novel acute promyelocytic leukemia fusion protein, with retinoic acid receptor and STAT3 signaling pathways. Blood 99, 2637–2646 10.1182/blood.V99.8.2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteve J., Escoda L., Martín G., Rubio V., Díaz-Mediavilla J., González M., Rivas C., Alvarez C., González San Miguel J. D., Brunet S., Tomás J. F., Tormo M., Sayas M. J., Sánchez Godoy P., Colomer D., Bolufer P., Sanz M. A., Spanish Cooperative Group PETHEMA (2007). Outcome of patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia failing to front-line treatment with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline-based chemotherapy (PETHEMA protocols LPA96 and LPA99): benefit of an early intervention. Leukemia 21, 446–452 10.1038/sj.leu.2404501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora R., Grimwade D. (2004). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR to detect fusion gene transcripts associated with AML. Methods Mol. Med. 91, 151–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman S. D., Jovanovic J. V., Grimwade D. (2008). Development of minimal residual disease directed therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Semin. Oncol. 35, 388–400 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabert J. A., Beillard E., van der Velden V. H. J., Bi W., Grimwade D., Pallisgaard N., Barbany G., Cazzaniga G., Cayuela J. M., Cavé H., Pane F., Aerts J. L., De Micheli D., Thirion X., Pradel V., González M., Viehmann S., Malec M., Saglio G., van Dongen J. J. (2003). Standardization and quality control studies of “real-time” quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of fusion gene transcripts for residual disease detection in leukemia – a Europe Against Cancer program. Leukemia 17, 2318–2357 10.1038/sj.leu.2403135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Biondi A., Mozziconacci M-J., Hagemeijer A., Berger R., Neat M., Howe K., Dastugue N., Jansen J., Radford-Weiss I., Lo Coco F., Lessard M., Hernandez J. M., Delabesse E., Head D., Liso V., Sainty D., Flandrin G., Solomon E., Birg F., Lafage-Pochitaloff M. (2000). Characterization of acute promyelocytic leukemia cases lacking the classic t(15;17): results of the European working party. Blood 96, 1297–1308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Gorman P., Duprez E., Howe K., Langabeer S., Oliver F., Walker H., Culligan D., Waters J., Pomfret M., Goldstone A., Burnett A., Freemont P., Sheer D., Solomon E. (1997). Characterization of cryptic rearrangements and variant translocations in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 90, 4876–4885 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Howe K., Langabeer S., Burnett A., Goldstone A., Solomon E. (1996). Minimal residual disease detection in acute promyelocytic leukemia by reverse-transcriptase PCR: evaluation of PML-RAR alpha and RAR alpha-PML assessment in patients who ultimately relapse. Leukemia 10, 61–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Jovanovic J. V., Hills R. K., Nugent E. A., Patel Y., Flora R., Diverio D., Jones K., Aslett H., Batson E., Rennie K., Angell R., Clark R. E., Solomon E., Lo-Coco F., Wheatley K., Burnett A. K. (2009). Prospective minimal residual disease monitoring to predict relapse of acute promyelocytic leukemia and to direct pre-emptive arsenic trioxide therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 3650–3658 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Mistry A. R., Solomon E., Guidez F. (2010). Acute promyelocytic leukemia: a paradigm for differentiation therapy. Cancer Treat. Res. 145, 219–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade D., Tallman M. S. (2011). Should minimal residual disease monitoring be the standard of care for all patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia? Leuk. Res. 35, 3–7 10.1016/S0145-2126(11)70009-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidez F., Parks S., Wong H., Jovanovic J. V., Mays A., Gilkes A. F., Mills K. I., Guillemin M. C., Hobbs R. M., Pandolfi P. P., de Thé H., Solomon E., Grimwade D. (2007). RARalpha-PLZF overcomes PLZF-mediated repression of CRABPI, contributing to retinoid resistance in t(11;17) acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18694–18699 10.1073/pnas.0704433104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga E., Nakamura M., Nanri T., Kawakita T., Horikawa K., Mitsuya H., Asou N. (2009). Acute promyelocytic leukemia harboring a STAT5B-RARA fusion gene and a G596V missense mutation in the STAT5B SH2 domain of the STAT5B-RARA. Eur. J. Haematol. 83, 499–501 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01324.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurcic J. G., Nimer S. D., Scheinberg D. A., DeBlasio T., Warrell R. P., Jr., Miller W. H., Jr. (2001). Prognostic significance of minimal residual disease detection and PML/RAR-alpha isoform type: long-term follow-up in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 98, 2651–2656 10.1182/blood.V98.9.2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore B., Stewart A., Jovanovic J., Craddock C., Grimwade D. (2010). Arsenic trioxide and stem cell transplantation is an effective salvage therapy in patients with relapsed APL. Br. J. Haematol. 149(Suppl. 1), 22. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08079.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T., Mori A., Darmanin S., Hashino S., Tanaka J., Asaka M. (2008). The seventh pathogenic fusion gene FIP1L1-RARA was isolated from a t(4;17)-positive acute promyelocytic leukemia. Haematologica 93, 1414–1416 10.3324/haematol.12854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krönke J., Schlenk R. F., Jensen K. O., Tschürtz F., Corbacioglu A., Gaidzik V. I., Paschka P., Onken S., Eiwen K., Habdank M., Späth D., Lübbert M., Wattad M., Kindler T., Salih H. R., Held G., Nachbaur D., von Lilienfeld-Toal M., Germing U., Haase D., Mergenthaler H. G., Krauter J., Ganser A., Göhring G., Schlegelberger B., Döhner H., Döhner K. (2011). Monitoring of minimal residual disease in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the German-Austrian Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 2709–2716 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakabe M., Suzukawa K., Nanmoku T., Obara N., Okoshi Y., Mukai H. Y., Hasegawa Y., Kojima H., Kawakami Y., Ninomiya H., Nagasawa T. (2008). Detection of the STAT5B-RARA fusion transcript in acute promyelocytic leukemia with the normal chromosome 17 on G-banding. Eur. J. Haematol. 80, 444–447 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01042.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht J. D., Chomienne C., Goy A., Chen A., Scott A. A., Head D. R., Michaux J. L., Wu Y., DeBlasio A., Miller W. H., Jr., Zelenetz A. D., Willman C. L., Chen Z., Chen S.-J., Zelent A., Macintyre E., Veil A., Cortes J., Kantarjian H., Waxman S. (1995). Clinical and molecular characterization of a rare syndrome of acute promyelocytic leukemia associated with translocation (11;17). Blood 85, 1083–1094 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco F., Diverio D., Avvisati G., Petti M. C., Meloni G., Pogliani E. M., Biondi A., Rossi G., Carlo-Stella C., Selleri C., Martino B., Specchia G., Mandelli F. (1999). Therapy of molecular relapse in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 94, 2225–2229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo-Coco F., Romano A., Mengarelli A., Diverio D., Iori A. P., Moleti M. L., De Santis S., Cerretti R., Mandelli F., Arcese W. (2003). Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for advanced acute promyelocytic leukemia: results in patients treated in second molecular remission or with molecularly persistent disease. Leukemia 17, 1930–1933 10.1038/sj.leu.2403078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry A. R., Pedersen E. W., Solomon E., Grimwade D. (2003). The molecular pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukaemia: implications for the clinical management of the disease. Blood Rev. 17, 71–97 10.1016/S0268-960X(02)00075-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman F., Johansson B., Mertens F. (eds). (2011). Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations, and Gene Fusions in Cancer. Available at: http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman

- Ommen H. B., Schnittger S., Jovanovic J. V., Ommen I. B., Hasle H., Østergaard M., Grimwade D., Hokland P. (2010). Strikingly different molecular relapse kinetics in NPM1c, PML-RARA, RUNX1-RUNX1T1, and CBFB-MYH11 acute myeloid leukemias. Blood 115, 198–205 10.1182/blood-2009-04-212530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao C., Zhang S. J., Chen L. J., Miao K. R., Zhang J. F., Wu Y. J., Qiu H. R., Li J. Y. (2011). Identification of the STAT5B-RARalpha fusion transcript in an acute promyelocytic leukemia patient without FLT3, NPM1, c-Kit and C/EBPalpha mutation. Eur. J. Haematol. 86, 442–446 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01595.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redner R. L., Rush E. A., Faas S., Rudert W. A., Corey S. J. (1996). The t(5;17) variant of acute promyelocytic leukemia expresses a nucleophosmin-retinoic acid receptor fusion. Blood 87, 882–886 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M. A., Grimwade D., Tallman M. S., Lowenberg B., Fenaux P., Estey E. H., Naoe T., Lengfelder E., Büchner T., Döhner H., Burnett A. K., Lo-Coco F. (2009). Management of acute promyelocytic leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 113, 1875–1891 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittger S., Kern W., Tschulik C., Weiss T., Dicker F., Falini B., Haferlach C., Haferlach T. (2009). Minimal residual disease levels assessed by NPM1 mutation-specific RQ-PCR provide important prognostic information in AML. Blood 114, 2220–2231 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells R. A., Catzavelos C., Kamel-Reid S. (1997). Fusion of retinoic acid receptor alpha to NuMA, the nuclear mitotic apparatus protein, by a variant translocation in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nat. Genet. 17, 109–113 10.1038/ng0997-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y., Tsuzuki S., Tsuzuki M., Handa K., Inaguma Y., Emi N. (2010). BCOR as a novel fusion partner of retinoic acid receptor alpha in a t(X;17)(p11;q12) variant of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 116, 4274–4283 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. W., Yan X. J., Zhou Z. R., Yang F. F., Wu Z. Y., Sun H. B., Liang W. X., Song A. X., Lallemand-Breitenbach V., Jeanne M., Zhang Q. Y., Yang H. Y., Huang Q. H., Zhou G. B., Tong J. H., Zhang Y., Wu J. H., Hu H. Y., de Thé H., Chen S. J., Chen Z. (2010). Arsenic trioxide controls the fate of the PML-RARalpha oncoprotein by directly binding PML. Science 328, 240–243 10.1126/science.1189732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]