Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

The 2010 Affordable Care Act mandates that health insurance companies make those up to age 26 eligible for their parents’ policies. Thirty-four states previously enacted similar laws. The authors sought to examine the impact on access to care of state laws extending eligibility of parents’ insurance to young adults.

METHODS:

By using a difference-in-differences analysis, we examined the 2002–2004 and 2008–2009 Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System to compare 3 states enacting laws in 2005 or 2006 with 17 states that have not enacted laws on 4 outcomes: self-reported health insurance coverage, identification of a personal physician/clinician, physical exam from a physician within the past 2 years, and forgoing care in the past year due to cost.

RESULTS:

For each outcome there was differential improvement among states enacting laws compared with states without laws. Health insurance differentially increased 0.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], −3.8% to 4.2%), from 67.6% to 68.1% pre-post in states enacting laws and from 68.5% to 68.7% in states without. Personal physician/clinician identification differentially increased 0.9% (95% CI −3.1% to 5.0%), from 62.4% to 65.5% in states enacting laws and from 58.0% to 60.2% in states without. Recent physical exams differentially increased significantly 4.6% (95% CI, 0%–9.2%), from 77.3% to 81.2% in states enacting laws and from 76.2% to 75.5% in states without. Forgone care due to cost differentially decreased significantly 3.9% (95% CI, −0.3% to −7.5%), from 20.4% to 18.2% in states enacting laws and from 17.8% to 19.4% in states without.

CONCLUSIONS:

States that expanded eligibility to parents’ insurance in 2005 or 2006 experienced improvements in access to care among young adults.

KEY WORDS: parental insurance, state laws, Affordable Care Act

What's Known on This Subject:

Prior to the Affordable Care Act of 2010, 34 states enacted laws extending eligibility for parents’ health insurance to adult children. Few studies have examined their impact; a single study found no change in insurance 1 year after enactment.

What This Study Adds:

States that expanded parents’ insurance eligibility to young adults were associated with higher rates of insurance coverage, identification of a personal clinician, physical exams, and lower forgone care due to cost. The Affordable Care Act may similarly improve access to care.

The first of several key provisions contained within the recently enacted Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 have recently gone into effect, one of which requires that health insurance plans allow parents to extend coverage to their children aged 18 to 26 years.1,2 This provision was designed in part to enhance access to health care for young adults who are known to have disproportionately high rates of uninsurance, in large part due to aging out of eligibility for public and private plans at their 19th birthday. Moreover, most entry-level jobs lack employer-based health insurance.3 Although they compose just 17% of adults <65 years old, adults between the ages of 19 and 29 account for almost 30% of uninsured adults <65 years old.3

Innovation at the state level frequently precedes federal action: 34 states enacted laws to extend coverage eligibility to dependent youth over the past 3 decades. These laws vary in many important details, including eligibility criteria with respect to age, student status, and marital status. However, there have been limited evaluations of their impact on access to care. One earlier study found no increase in the rate of insurance among dependent youth in 19 states with such laws.4 However, this study did not include a control group for comparison, considered the laws’ impact only on insurance coverage status and, for many states, only examined the laws’ impact during the year after enactment.

To more broadly evaluate the impact of state laws extending eligibility of parents’ health insurance coverage to dependent youth, we used the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a nationally representative survey of the civilian US population. The BRFSS offers a unique opportunity to examine state laws’ impact on several markers of access to care at the state level, comparing several years before and after enactment of the state laws. Our objective was to determine whether enactment of state insurance extension laws in 2005 or 2006 was associated with increased access to care compared with states without such laws among young adults aged 19 to 23 years. This research is relevant to and will inform expectations for the possible impact of the eligibility extension provision within the ACA.

METHODS

Data Source

We used the BRFSS, an annual telephone survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in collaboration with state health departments. Consistent with standard approaches for longitudinal data analysis, we used data from the BRFSS from 2 periods of time: before the state laws were enacted (2002–2004) and after the state laws were enacted (2008 and 2009); the period from 2005 to 2007 served as a “washout,” or implementation, period.5,6

Study Design and Sample

We evaluated the results of this natural experiment in health policy, by using a multiple time series with a comparison group as a control.7 The analysis of such a design is commonly referred to as a difference-in-differences analysis, as we compared outcome differences pre-post between 2 independent samples. This strong quasi-experimental design allowed us to examine the impact of laws that extend eligibility to dependent youth while reducing bias from unmeasured variables and from secular trends.7,8

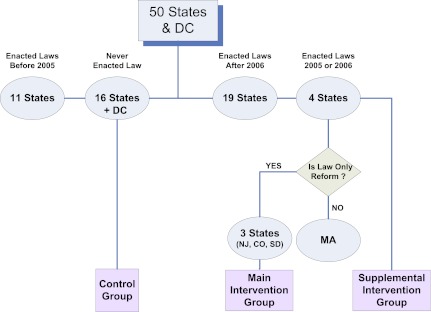

We conducted 2 sets of analyses, each of which used a different sample and comparison group. For our primary analysis, we compared those aged 19 to 23 years old living in states that did and in states that did not enact laws that extended eligibility. There were 4 states that enacted laws to extend eligibility in 2005 or 2006: Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and South Dakota (Table 1). In our main analysis, we excluded Massachusetts because its state law included a population mandate to obtain health insurance coverage. However, given the ACA’s similar inclusion of a population mandate, we repeated analyses including Massachusetts. Seventeen states (including Washington, DC) had no extension laws in place through the end of 2010 (see Supplemental Fig 2). Individuals from the remaining 31 states were excluded because they lived in states that enacted laws before or sometime during the period of study (Fig 1).

TABLE 1.

Key Characteristics of State Laws Enacted in 2005 or 2006 Extending Eligibility to Dependent Youth to Their Parents’ Health Insurance Plans

| State | Effective Date | Eligibility Criteria | Coverage Subsidies or Premium Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SD | July 2005 | Fulltime students <24 y olda | None |

| CO | January 2006 | Unmarried child <25 y old who lived at the same address as the parent or financially dependent | None |

| NJ | January 2006 | State residents or full-time students <30 y old | Premiums capped at 102% |

| MAb | June 2006 | State residents or full-time students <26 y old | Subsidies for insurance coverage |

Law was amended in 2007 to allow those who were full-time students at age 24 to remain on their parents’ plan if they remained full-time student until age 29.

Massachusetts enacted legislation in 2006 but was excluded from our main analyses because of an accompanying mandate to obtain insurance coverage.

FIGURE 1.

State insurance eligibility extension legislation among the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Control states were compared with the intervention states both with and without the inclusion of Massachusetts (which enacted legislation in 2006), because eligibility extension in Massachusetts was part of a larger health care reform law that included an insurance coverage mandate.

The second analysis included only states that enacted laws and compared populations affected with those not affected by the law as the intervention and control groups. For our secondary analysis, we compared cohorts of nonstudents aged 19 to 23 years old to nonstudents aged 26 to 29 years old in 2 states (Colorado and South Dakota) that enacted laws defining 24 years as the upper age limit to remain on their parents’ insurance. Students were excluded because South Dakota amended their law in 2007 to allow full-time students to remain on their parents’ insurance until age 29. Although we recognize that the 2 age groups may differ in meaningful ways, we do not expect such differences to have changed over the study period and thus do not expect them to have biased our findings.

Outcome Measures

Our outcome of interest was the impact of the laws on access to care. We used 4 self-reported measures from the BRFSS as proxies of access to care: having any health insurance; having a personal physician/clinician (PMD), having had a routine checkup within the previous 2 years; and having forgone health care because of cost. All respondents were asked the following questions. (1) “Do you have any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as HMOs, or government plans such as Medicare?” We categorized those responding “No” as being without insurance. (2) “Do you have one person you think of as your personal doctor or health care provider?” Those who answered that they did not were asked, “Is there more than one, or is there no person who you think of as your personal doctor or health care provider?” We defined those responding “No” to questions as not identifying a PMD. (3) “About how long has it been since you last visited a doctor for a routine checkup? A routine checkup is a general physical exam, not an exam for a specific injury, illness, or condition.” We categorized replies as indicating ≤2 years and otherwise. (4) “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?” We categorized those responding “Yes” as having forgone care due to cost. In keeping with BRFSS design, some questions were not asked each year. The question concerning forgone care was not asked in 2002, while the question regarding receipt of a physical exam was not asked until 2005; we used that year to represent the preenactment period. We recognize that use of 2005 data could bias our findings toward the null to the extent that the preenactment period was contaminated by postenactment behavior during the latter half of 2005 in South Dakota, although we expect such contamination to be small. Otherwise, all questions were asked in all years.

Statistical Analysis

We described respondent characteristics by using proportions and frequency analysis. Although not strictly required by our research design, we present the comparability of residents between the 2 groups of states. We contrasted the characteristics of 19- to 23-year-olds in “implementation” and “control” states with respect to individual sociodemographic characteristics (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Population Characteristics for 19- to 23-Year-Olds for 3 States That Enacted Extension Eligibility Laws in 2005 or 2006 and the 17 States Without Legislation, 2002–2004 and 2008–2009

| States Enacting Laws (3 states, n = 3473) | States Without Laws (17 states, n = 17 173) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 19–20 y, % | 37.2a | 38.8 | .64 |

| Female gender, % | 48.1 | 47.7 | .80 |

| Race, % | <.001 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 23.1 | 26.4 | |

| White | 58.8 | 50.6 | |

| Black | 9.3 | 11.0 | |

| Other | 8.3 | 11.7 | |

| Education, % | <.001 | ||

| No high school diploma | 10.3 | 13.2 | |

| High school diploma | 32.7 | 35.8 | |

| Some college | 56.7 | 51.0 | |

| Marital status, % | <.001 | ||

| Never married | 85.3 | 82.7 | |

| Divorced, widowed, separated | 1.8 | 2.3 | |

| Married | 12.6 | 15.1 | |

| Self-reported health status, % | .35 | ||

| Excellent | 25.2 | 23.7 | |

| Very good/good | 64.1 | 67.2 | |

| Fair | 9.1 | 7.9 | |

| Poor | 1.7 | 1.2 | |

| Employment, % | .002 | ||

| Employed for wages | 51.9 | 48.3 | |

| Self-employed | 4.2 | 4.3 | |

| Out of work for >1 y | 2.4 | 3.6 | |

| Out of work for <1 y | 9.6 | 9.6 | |

| Homemaker | 3.9 | 5.2 | |

| Student | 25.9 | 26.7 | |

| Unable to work | 1.8 | 2.3 | |

| Annual household income, % | <.001 | ||

| $0 to $24 999 | 31.5 | 38.3 | |

| $25 000 to $35 000 | 10.6 | 11.2 | |

| $35 000 to $$50 000 | 12.0 | 11.4 | |

| >$50 000 | 24.9 | 21.0 | |

| Missing | 20.7 | 18.1 |

Sums may not round to 100 due to rounding.

For our primary analysis, we compared pre-post (before-after) differences for each access-to-care outcome measure among young adults aged 19 to 23 years in intervention states to the differences in control states, both with and without the inclusion of Massachusetts as an intervention state. Our secondary analysis compared pre-post differences in young adults aged 19 to 23 years to nonstudents aged 26 to 29 years in Colorado and South Dakota.

All analyses took into account the complex survey design of the data source and were performed by using Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 2332 BRFSS respondents aged 19 to 23 years between 2002 and 2004 (preenactment) from the 3 states that enacted extension laws in 2005 or 2006 and 1141 from 2008 to 2009 (postenactment), along with 1036 and 816 from Massachusetts, respectively. There were 11 302 and 5871 from the 17 states (including Washington, DC) without extension laws, respectively. Young adults in states that did and did not enact laws were similar with respect to age, gender, and self-reported health status, but states that enacted laws had higher proportions of respondent who were Caucasian, more educated, not married, and worked for wages (P < .002; Table 2).

Access to Care

Comparison of States With and Without Extension Laws

Markers of access to care consistently improved among those aged 19 to 23 in states that enacted laws but did not consistently improve in states that did not enact laws (Table 3). Health insurance differentially increased by 0.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], −3.8% to 4.2%; P = .93), from 67.6% to 68.1% pre-post in states enacting laws and from 68.5% to 68.7% in states without. PMD identification differentially increased by 0.9% (95% CI, −3.1% to 5.0%; P = .65), from 62.4% to 65.5% pre-post in states enacting laws and from 58.0% to 60.2% in states without. Recent physical exams differentially increased by 4.6% (95% CI, 0%–9.2%; P = .05), from 77.3% to 81.2% pre-post in states enacting laws and from 76.2% to 75.5% in states without. Finally, forgone care differentially decreased by 3.9% (95% CI, −0.3% to −7.5%; P = .03), from 20.4% to 18.2% pre-post in states enacting laws and from 17.8% to 19.4% in states without. When analyses were repeated including Massachusetts as an intervention state, the differential improvements were even greater: 3.6% (95% CI, 0.5%–6.7%; P = .02) for health insurance, 1.7% (95% CI, −1.7% to 5.0%; P = .33) for PMD identification, 2.7% (95% CI, −1.0% to 6.4%; P = .16) for recent physical exam, and 4.3% (95% CI, −1.4% to −7.1; P = .003) for forgone care.

TABLE 3.

Access to Care and Preventive Care Among Young Adults 19 to 23 Years Old in States Enacting Extension Eligibility Laws in 2005 and 2006 and in States Without These Laws During a Period Before Enactment (2002–2004) and After Enactment (2008–2009), Along With the Differential Changes in These Outcomes

| State Sample | Sample Size, No. | Before, % (2002–2004)a | After, % (2008–2009) | Before-After Difference, % | Difference in Differences, % (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health insurance coverage | |||||

| No law | 16 973 | 68.5 (67.5 to 69.4) | 68.7 (67.4 to 70.1) | 0.3 (−1.4 to 1.9) | — |

| Extension laws (without MA) | 3442 | 67.6 (65.5 to 69.7) | 68.1 (65.1 to 71.0) | 0.4 (−3.2 to 4.1) | 0.2 (−3.8 to 4.2) |

| Extension laws (with MA) | 5278 | 71.1 (69.4 to 72.8) | 74.9 (72.8 to 77.1) | 3.9 (1.1 to 6.6) | 3.6 (0.5 to 6.7) |

| Identification of a personal physician/clinician or health care provider | |||||

| No law | 17 066 | 58.0 (59.0 to 57.0) | 60.2 (58.8 to 61.6) | 2.2 (0.5 to 3.9) | — |

| Extension laws (without MA) | 3459 | 62.4 (60.2 to 64.5) | 65.5 (62.5 to 68.5) | 3.2 (−0.5 to 6.9) | 0.9 (−3.1 to 5.0) |

| Extension laws (with MA) | 5298 | 64.3 (62.5 to 66.1) | 68.2 (65.9 to 70.4) | 3.9 (1.0 to 6.8) | 1.7 (−1.7 to 5.0) |

| Physical examination in past 2 y | |||||

| No law | 9859 | 76.2 (74.8 to 77.7) | 75.5 (74.3 to 76.7) | −0.7 (−2.6 to 1.1) | — |

| Extension laws (without MA) | 1839 | 77.3 (74.0 to 80.6) | 81.2 (78.6 to 83.7) | 3.9 (−0.2 to 8.0) | 4.6 (0 to 9.2) |

| Extension laws (with MA) | 2906 | 81 (78.4 to 83.7) | 83 (81.1 to 84.8) | 2.0 (2.0 to 5.2) | 2.7 (−1.0 to 6.4) |

| Forgone care due to cost | |||||

| No law | 13 327 | 17.8 (16.8 to 18.7) | 19.4 (18.3 to 20.5) | 1.7 (0.2 to 1) | — |

| Extension laws (without MA) | 2801 | 20.4 (18.3 to 22.6) | 18.2 (15.7 to 20.7) | −2.2 (−5.5 to 1.0) | −3.9 (−0.3 to −7.5) |

| Extension laws (with MA) | 4277 | 18.6 (16.9 to 20.3) | 16.0 (14.2 to 17.8) | −2.6 (−0.1 to −5.1) | −4.3 (−1.4 to −7.1) |

States enacting eligibility extension laws in 2005 or 2006 included Colorado, New Jersey, and South Dakota, along with Massachusetts (MA). Results are presented both with and without MA. There were 17 states without laws, including the District of Columbia.

Difference in differences compares the before-after difference among states enacting extension laws in 2005 or 2006 with the before-after difference among states without extension laws.

Comparison of 19- to 23-Year-Olds and 26- to 29-Year-Olds in States With Extension Laws

All 4 markers of access to care differentially improved among those aged 19 to 23 years compared with nonstudents aged 26 to 29 years in the 2 states that enacted laws with an eligibility limit of 26 years (Table 4). Health insurance differentially increased by 4.2% (95% CI, −1.6% to 10.1%; P = .16), from 67.4% to 67.6% pre-post among 19- to 23-year-olds and from 76.7% to 72.7% among 26- to 29-year-olds. PMD identification differentially increased by 3.8% (95% CI, −2.3% to 9.9%; P = .23), from 60.2% to 62.6% among 19- to 23-year-olds and from 67.6% to 66.3% among 26- to 29-year-olds. Physical exam differentially increased by 2.1% (95% CI, −5.7% to 10%; P = .59), from 72.5% to 71.7% among 19- to 23-year-olds and from 68.3% to 65.3% among 26- to 29-year-olds. Forgone care differentially decreased 8.0% (95% CI, −2.5% to −13.5%; P = .004), from 18.9% to 19.2% among 19- to 23-year-olds and from 14.5% to 22.7% among 26- to 29-year-olds.

TABLE 4.

Access to Care and Preventive Care in Colorado and South Dakota, Both of Which Enacted Eligibility Extension Laws in 2005 Applicable to Dependent Children <26 Years Old, Among Young Adults 19 to 23 Years Old and 26 to 29 years Old During a Period Before Enactment (2002–2004) and After Enactment (2008–2009), Along With the Differential Changes in These Outcomes

| Sample Age Group | Sample Size, No. | Before, % (2002–2004) | After, % (2008–2009) | Before-After Difference, % | Difference in Differences, % (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health insurance coverage | 4.2 (−1.6 to 10.1) | ||||

| 19–23 y | 2102 | 67.4 (64.7 to 70.1) | 67.6 (63.9 to 71.4) | 0.2 (−4.4 to 4.9) | |

| 26–29 y | 2790 | 76.7 (74.4 to 79.0) | 72.7 (69.9 to 75.5) | −4.0 (−7.6 to −0.4) | |

| Identification of a personal physician/clinician or health care provider | 3.8 (−2.3 to 9.9) | ||||

| 19–23 y | 2114 | 60.2 (57.4 to 63.0) | 62.6 (58.7 to 66.5) | 2.4 (−2.3 to 7.2) | |

| 26–29 y | 2822 | 67.6 (65.2 to 70.1) | 66.3 (63.3 to 69.2) | −1.3 (−5.2 to 2.5) | |

| Physical examination in past 2 y | 2.1 (−5.7 to 10.0) | ||||

| 19–23 y | 1095 | 72.5 (67.7 to 77.3) | 71.7 (68.0 to 75.3) | −0.9 (−6.9 to 5.2) | |

| 26–29 y | 1735 | 68.3 (64.3 to 72.3) | 65.3 (62.2 to 68.4) | −3.0 (−8.0 to 2.0) | |

| Forgone care due to cost | −8.0 (−2.5 to −13.5) | ||||

| 19–23 y | 1659 | 18.9 (16.2 to 21.7) | 19.2 (16.0 to 22.3) | 0.2 (−3.9 to 4.4) | |

| 26–29 y | 2154 | 14.5 (12.1 to 16.8) | 22.7 (20.0 to 25.3) | 8.2 (4.6 to 11.8) |

Difference in differences compares the before-after difference among young adults aged 19 to 23 y with the before-after difference among young adults aged 26 to 29 y.

Discussion

State laws extending eligibility of parents’ health insurance coverage to dependent youth were associated with improved access to care, particularly higher reports of health recent physical exams and lower reports of forgoing care due to cost. We found differential improvements in access to care by using 2 independent approaches, by comparing 19- to 23-year-olds in states with and without laws and by comparing 19- to 23-year-olds and 26- to 29-year-olds in 2 states that enacted laws limiting dependent eligibility to 24 years or younger.

Although we found differential improvements across all 4 access-to-care measures, the magnitude of the impact varied. We observed small differential improvements in insurance coverage and PMD identification but larger improvements in physical exams and not forgoing care. These results suggest that extension eligibility laws may have allowed young adults to move from less to more generous health insurance coverage (as provided by their parents’ employer-based plans), facilitating clinical contact via a physical exam. Therefore, while insurance coverage improved marginally, covered services improved such that dependent youth were less frequently forgoing care due to costs. Furthermore, our analyses including Massachusetts suggest that the individual mandate to obtain insurance was a powerful adjunct to the eligibility extension. Nearly all measures of access to care and preventive care improved significantly, with substantially larger differential improvements, with the exception of physical exams. In the context of Massachusetts’ mandate, demand for access to physicians may have increased and thus limited respondents’ ability to obtain a physical exam from the limited number of primary care physicians.9

The modest, but meaningful, improvements we observed in access to care occurred despite limitations of the state laws. For example, while these laws extended eligibility, they did not require that parents purchase coverage for dependent youth. Furthermore, the laws provided no subsidies to offset the cost of purchasing coverage and only 1 of the 3 intervention states in the main analysis limited increases on premiums. Adding a child to their policy may have made coverage unaffordable for some proportion of young adults and their parents, regardless of the value they placed on it. Thus, it may have been wealthier parents, or those with sick children, who took advantage of their state law.

One motivation for this work was to anticipate potential impacts of the provision of the ACA that extends insurance eligibility to young adults. There are several reasons that our findings may underestimate the impact of the ACA. Like the state laws, the ACA makes young adults eligible for their parents’ private health insurance plans. Unlike the state laws, the ACA applies to all individuals aged 18 to 26 years old and is not subject to limitations on state mandates. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) exempts self-insured employers from state (but not federal) insurance regulation.10 As half of privately insured adults in the United States are insured under self-insured plans, our analysis of state laws’ impacts almost certainly underestimates the ACA’s likely impact.11

There are other differences between the state laws and the ACA provision that have implications for the ACA’s potential impact. The ACA mandates eligibility for individuals younger than age 26 regardless of their marital, student, or dependent status; many states cover only the unmarried, full-time students, or dependent children who live at home with their parents. In addition, the ACA requires young adults to be included in any family insurance plan, but many state laws allow coverage only through riders, a separate plan added onto the parents’ policy. Finally, under the ACA, and unlike most state laws, premiums and benefits cannot be different for offspring of different ages. All of these conditions suggest a larger potential impact. However, in contrast, the ACA extends eligibility only to age 26, offers no subsidies, and imposes no caps on premium increases, whereas 6 states extend eligibility beyond 26 years and 4 impose premium caps. In sum, the ACA is likely to increase insurance uptake more than state laws because it supersedes ERISA, broadens eligibility to nonstudents and married dependent children, and allows children access to the same benefits as their parents and siblings. However, the ACA could have been designed to reach even more young adults had its age limit been 29, or if it had included regulated premiums, as some states have done.

Our study has several key strengths. We used a strong quasi-experimental approach that included a before-after comparison by using a difference-in-differences analysis and used 2 approaches to determine the impact of these state eligibility extension laws, comparing states that enacted and did not enact laws and comparing targeted and nontargeted age groups within states that enacted laws. However, our study also has limitations. The BRFSS provides self-reported data from a large, representative survey examining health risks and behaviors. Some questions that could have improved our study were not asked, such as whether young adults obtained insurance coverage independently or through their parents’ insurance policy, and some questions were not asked every year. In addition, the use of population data does not allow assessment of how well insurers complied with state requirements to extend insurance coverage eligibility. Finally, like any observational study, our findings are susceptible to unmeasured confounding. However, this last concern is largely mitigated by our multiple time series with control group design and our comparisons both across and within states, as mentioned earlier.

CONCLUSIONS

Ensuring access to care is of critical importance. State laws that extended eligibility of parents’ insurance to their young adult children were associated with improved access to care, particularly with respect to having a physical exam and not forgoing care. Our study suggests that a comparable provision within the ACA may similarly result in improved access to care and offers suggestions regarding both the strengths and limitations of that provision.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marie Diener-West, PhD, for biostatistical guidance.

Glossary

- ACA

Affordable Care Act

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- CI

confidence interval

- ERISA

Employee Retirement Income Security Act

- PMD

personal physician or clinician

Footnotes

Deceased.

Dr Blum had access to all of the data collected in the study and performed the statistical analysis reported in the article. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors contributed to the content of the manuscript, the design and conduct of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and the preparation of the manuscript. Dr Blum had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This project was not directly supported by any external grants or funds. Dr Blum was supported through a National Research Service Award from the Health Resources & Administration at Mount Sinai School of Medicine (T32HP10262). He currently is an American Association for the Advancement of Sciences fellow in the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the National Institutes of Health. Dr Ross is currently supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08AG032886) and the American Federation of Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Dr Ross receives financial support from the FAIR Health, Inc Scientific Advisory Board. Dr Blum was a paid consultant to the Committee of Interns and Residents of the Service Employees International Union (CIR/SEIU). No sponsor had any role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Title I, Part A, Subpart II, Sec. 2714 Pub. L 111-148, 124 (2010)

- 2.Group health plans and health insurance issuers relating to dependent coverage of children to age 26 under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Fed Register 2010;75(92):27122–27139 [PubMed]

- 3.Collins SR, Nicholson JL. Rite of passage: young adults and the Affordable Care Act of 2010. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2010;87:1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monheit AC, Cantor JC, DeLia D, Belloff D. How have state policies to expand dependent coverage affected the health insurance status of young adults? Health Serv Res. 2011;46(1 pt 2):251–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soumerai SB, Avorn J, Ross-Degnan D, Gortmaker S. Payment restrictions for prescription drugs under Medicaid. Effects on therapy, cost, and equity. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(9):550–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell DT, Stanley JC, Gage NL. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Chicago, IL: R. McNally; 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research Dallas, TX: Houghton Mifflin Co; 1963:56–63

- 9.Sack K. In Massachusetts, Universal Coverage Strains Care. New York Times. April 5th, 2008

- 10.Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). 29 U.S.C. § 1001 et seq 1974

- 11.Gabel JR, Jensen GA, Hawkins S. Self-insurance in times of growing and retreating managed care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(2):202–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.