Abstract

Behavioral inhibition (BI) has generally been treated as a unitary construct and assessed by combining ratings of fear, vigilance, and avoidance to both novel social and non-social stimuli. However, there is evidence suggesting that BI in social contexts is not correlated with BI in non-social contexts. The present study examined the distinction between social and non-social BI in a community sample of 559 preschool-age children using a laboratory assessment of child temperament, a diagnostic interview, and parent-completed questionnaires. Social and non-social BI were not significantly correlated and exhibited distinct patterns of associations with parent reports of temperament and anxiety symptoms. This study suggests that BI is heterogeneous, and that distinguishing between different forms of BI may help account for the variation in trajectories and outcomes exhibited by high BI children.

Behavioral inhibition (BI) is generally defined as the child’s initial behavioral reactions of fearfulness, wariness, and low approach to unfamiliar people, objects, and contexts [1]. As reported by Kagan and colleagues, BI can be observed as early as infancy and is estimated to characterize approximately 15% of children [2–4]. BI overlaps with a variety of other constructs, including fearfulness [5, 6], social withdrawal [7], and a variety of subtypes of social withdrawal, such as shyness [8], social reticence [9], and anxious-solitude [10]. However, fearfulness is a broader construct than BI, which is restricted to fear of novel stimuli. The various forms of social withdrawal overlap with BI in their emphasis on wariness and fear in social situations and difficulties in social skills and relationships. However, BI stresses the unfamiliarity of the stimuli and includes fear and wariness in novel non-social contexts.

A considerable body of research on BI has concentrated on its stability across childhood. Although BI is often assumed to be moderately stable, stability estimates have ranged from .24 to .64 [4, 8, 11–17]. Indeed, only a minority of children classified as inhibited in toddlerhood remained inhibited in middle childhood [18, 19].

Similar to research on the stability of BI, a number of studies have examined associations between BI and risk for various forms of psychopathology. Studies of the offspring of parents with panic disorder have revealed elevated rates of BI [e.g., 20–23]. However, some studies find that BI is also associated with mood disorders in parents [e.g., 23, 24], while other studies do not support an association between parental depression and child BI [e.g., 22, 25].

Researchers have also examined whether BI predicts the development of anxiety disorders in later childhood [e.g., 26–29] and adolescence [e.g., 30–34]. Results of these studies have indicated that behaviorally inhibited children and adolescents display higher rates of anxiety, particularly social anxiety, compared to those individuals with an uninhibited temperament; however, there is less agreement regarding other types of anxiety disorders [e.g., 26–28; 35]. Further, Caspi and colleagues (1996) found that BI in early childhood predicted depression but not anxiety in adulthood [36]. Thus, evidence regarding the specificity of associations between BI and particular internalizing disorders is inconsistent.

In sum, both the stability of BI and its associations with risk for psychopathology differ across studies and samples. This variation may be related to a number of characteristics, including differences in the age, size, and type (community versus clinic) of sample, assessement instruments, and study design (see [37] for a detailed review of the designs and methods of these studies). However, another possible explanation for these findings is that BI is a heterogeneous, or multidimensional, construct.

BI as a Multidimensional Construct

BI in young children is generally assessed using standardized laboratory batteries that combine ratings of fear, vigilance, and avoidance associated with both novel social and non-social stimuli [e.g., 1, 18, 19, 23, 24, 38, 39, 40]. We are aware of three studies that have examined the association between social and non-social BI in laboratory observations. In a sample of toddlers, Kochanska [24] found that inhibition in social and non-social contexts was not significantly associated (r = .00). Rubin et al. [40] also reported a non-significant correlation (r = .12) between young children’s inhibition in non-social situations and situations with adults. More recently, in two assessments of a sample of 4-year-old children, Majdandzic and van den Boom [39] found situational variability in the children’s expression of fear in three laboratory tasks designed to elicit fearful reactions, two of which used social stimuli (i.e., approach by a stranger, exposure to an adult wearing frightening masks) and one utilizing non-social stimuli (i.e., an approaching toy animal). An examination of the intercorrelations of the three episodes revealed that the two episodes using social stimuli were moderately correlated, but neither was significantly correlated with the episode using non-social stimuli.

As an alternative to laboratory assessments, Bishop, Spence, and McDonald (2003) developed a parent- and teacher-report measure of BI [41]. Based on some of the data cited above suggesting that BI might not be a unitary construct, they developed subscales to assess children’s BI across six different contexts: unfamiliar adults, approaching peers, performance situations, preschool/separation, unfamiliar situations, and physical activities with minor risk. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the six subscales were distinct, but related. Most of the six subscales have at least some social content. However, inspection of the correlations between the latent factors indicates that the subscale with the least social content, physical activities with minor risk, exhibited the lowest correlations with the other subscales.

The distinction between social and non-social fear is consistent with research on anxiety disorders that demonstrates differences between social and non-social phobias at the phenotypic and genotypic levels. For example, in a sample of preschoolers, Spence, Rapee, McDonald, and Ingram [42] reported that social anxiety and fears of physical injury comprised independent factors in a confirmatory factor analysis. Additionally, multivariate genetic studies with samples of children and adolescents suggest that social and specific phobias have different genetic and environmental influences [43–45].

Finally, the leading biological explanation of BI is that it is the result of a hyperreactive amygdala [4, 18, 46]. In the phobias, amygdala activation appears to be specific to the feared class of stimuli. Thus, social phobics exhibit amygdala hyperreactivity to social, but not non-social, stimuli [47], while specific phobics do not exhibit increased amygdala reactivity in response to fearful faces [48]. While we are unaware of analogous studies for BI, these data suggest that social and non-social BI may exhibit similar stimulus specificity.

We seek to extend the nascent literature on the heterogeneity of BI by showing that social and non-social BI are not only independent, but also have different correlates. We assessed the associations between these two forms of BI in a large community sample of preschool aged children using a laboratory assessment of child temperament and determined if they exhibited differential associations with caregiver measures of temperament and anxiety disorder symptoms. We hypothesized that the laboratory indicies of social and non-social BI would not be significantly correlated. Furthermore, we posited that laboratory social BI would be associated with parent-reports of shyness, social phobia symptoms, and social BI, whereas laboratory non-social BI would be associated with parent-reports of fearfulness, specific phobia symptoms, and non-social BI.

Method

Participants

Recruitment

The sample included 559 children (54.0% male and 46.0% female) from Long Island, NY who lived with at least one English-speaking biological parent. The children were between 35 and 50 months (mean (SD) age = 42.2 (3.1) months; median age = 42.0 months). Children with significant medical conditions or developmental disabilities were excluded. Participants were recruited through commercial mailing lists. Of the 816 subjects who were contacted and eligible to participate, 69.1% (564/816) completed the initial laboratory visit. We compared those subjects who agreed to participate (N = 564) to those who declined to participate (N =252) on selected demographic variables collected in the phone screen. The groups did not differ significantly on gender of child, respondent education, respondent employment status, partner employment status, household income, marital status, and race/ethnicity. Following a detailed description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all the families. The families were financially compensated for their participation ($100 for the laboratory visit, $50 for the semi-structured diagnostic interview, $25 for the parent-report questionnaires). This study was conducted with full IRB approval.

Demographics

The sample was primarily Caucasian (87.1%) and middle class, as measured by the Hollingshead’s Four Factor Index of Social Status (M = 54.2; SD =11) [49]. The mean ages of the mothers and fathers were 36.0 (SD = 4.4) and 38.3 years (SD = 5.4), respectively. The majority (94.2%) of the children came from two-parent homes, and 51.4% of the mothers worked outside of the home part- or full-time. 55.0 % of the mothers and 47.0 % of the fathers had a college degree or higher. With regard to schooling, 59.8 % of the children attended preschool for an average of 8.54 hours per week. Most children had siblings: 12.2% had no siblings, 50.3 % had one sibling, 27.3% had two siblings, 8.2% had three siblings, and 2.3% had four or more siblings. Regarding birth order, 12.2% were only children, 25.0% were first born, 39.0% were second born, 23.9% had three or more older siblings. Children’s mean scores on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) were in the average range (M = 102.8, SD = 14) [50].

Assessment Procedures

The study consisted of a two and a half hour visit that included the child’s participation in a structured laboratory observation of temperament and behavior. The primary caregiver who accompanied the child completed a set of questionnaires. Most respondents were mothers (530 mothers; 25 fathers). The parent worked on the questionnaire packet during the visit but was allowed to finish any uncompleted forms at home and mail them back. Co-parents were sent a smaller packet of questionnaire to complete at home and return by mail. The diagnostic interview of psychopathology in preschoolers was conducted with the primary caregiver over the telephone, generally within several weeks after the laboratory visit.

Laboratory Assessment

The laboratory assessment included a standardized set of twelve laboratory episodes adopted from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab TAB) [51]. Three episodes (Risk Room, Stranger Approach, and Exploring New Objects) were selected because they are similar to those used in previous laboratory studies of BI [19}. Risk Room and Exploring New Objects assessed BI in non-social contexts, while Stranger Approach assessed BI in a social context. All of the episodes were videotaped through a one-way mirror and later coded.

Risk Room

The child was left alone to explore a set of novel and ambiguous stimuli, including a large black box with eyes and teeth, a cloth tunnel, a Halloween mask, balance beam, and small staircase. After five minutes, the experimenter returned to the room and asked the child to engage in play with each object.

Stranger Approach

The child was briefly left alone in the empty assessment room while the experimenter went to look for other toys. In the experimenter’s absence, a male research assistant entered the room and spoke to the child in a neutral tone while gradually walking closer to the child. At the end of the episode, the experimenter entered the room and introduced the male stranger to the child as her friend.

Exploring New Objects

The child was left alone to explore a set of novel and ambiguous stimuli, including pretend mice in a cage, sticky water-filled gel balls, a mechanical bird, a mechanical spider, and a pretend skull covered under a blanket. After five minutes, the experimenter returned and asked the child to play with each object.

Laboratory Coding Procedures

The three episodes were coded using Goldsmith et al.’s [51] coding system, which involved making highly specific ratings of emotional and behavioral responses at discrete time intervals (20–30 second epochs). The episodes were coded by graduate students, study staff, and undergraduate research assistants who completed extensive training. Coders were unaware of other study variables and had to reach at least 80% agreement with a “master” rater before coding independently. To examine interrater reliability, 28 of the videotapes were independently coded by a second rater. In order to calculate the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC), a two-way random, absolute agreement interrater ICC was used [52].

The non-social BI composite variable (α =.84, N = 542; ICC = .88, N = 35), was constructed by combining the following variables from the Risk Room and Exploring New Objects episodes: the average standardized ratings of latency to first fear response; facial, vocal and bodily fear; total number of objects touched; latency to touch objects; tentative play; referencing parent; proximity to parent; referencing experimenter; time spent playing; startle (only Exploring New Objects); sad facial affect (Exploring New Objects only); and latency to vocalize. The social BI composite variable (α = .56, N =542; ICC = .74, N = 35) included the following variables from the Stranger Approach episode: the average standardized ratings of latency to first fear response; facial, vocal and bodily fear; sad facial affect; latency to vocalize; approach towards the stranger; avoidance of the stranger; gaze aversion; and verbal/nonverbal interaction with the stranger. While the alpha for the social BI composite is lower than desirable, it should be noted that this variable, unlike the non-social BI variable, is based solely on one episode (i.e., fewer items). We chose to treat the BI variables as dimensions rather than categories because of the greater power of continuous variables and the lack of any precedent for dichotomizing social and non-social BI scores.

Questionnaires

Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ)

The CBQ is a widely used 194-item caregiver report measure of temperament for three- to seven-year-old children [6]. The caregiver is asked to rate the child’s behavior within the past six months on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely untrue of your child) to 7 (extremely true of your child). The CBQ has been shown to have adequate internal consistency (coefficient α’s for the 15 CBQ scales ranged from .67–.94, with a mean internal consistency estimate of .77) and good temporal stability (two-year stability estimates for maternal ratings from 5 to 7 years of age ranged from .50 to .79, with a mean of .65 across the 15 scales; stability estimates for father ratings ranged from .48 to .76, with a mean of .63) [6]. Parental agreement (a mean of .41 across scales when the children were 5 years of age, and a mean of .37 when the children were 7 years of age) and associations between temperament ratings and child social behavior provided evidence for satisfactory convergent validity [6]. Finally, structural analyses indicate that the CBQ has good construct validity, as the factor structure is consistent across cultures and age groups [6]. For the present study, we report data only from the primary parent (defined as the parent with the greatest responsibility for childcare) (N = 516) and co-parent (N = 394) fear and shyness scales. The fear scale was designed to assess the amount of negative affect, including unease, worry or nervousness related to anticipated pain or distress and/or potentially threatening situations. The shyness scale was designed to assess slow or inhibited approach in situations involving social novelty or uncertainity [6]. Exploratory factor analyses indicate that the fear scale loads on a Negative Affectivity factor, whereas the shyness scale has a negative loading on a Extraversion/Surgency factor, but also has a secondary loading on Negative Affectivity. Coefficient α for the parent fear and shyness scales in our sample was .74 and .92, respectively; for co-parent fear and shyness, α was .66 and .91, respectively.

Child Social Preference Scale (CSPS)

The CSPS consists of 11 items that were designed to assess children’s conflicted shyness and social disinterest [53]. Only the primary parent (N = 485) completed this measure. Items are rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). The CSPS has been shown to have satisfactory psychometric properties, with evidence suggesting that parents can reliably differentiate between the different social motivations that underlie conflicted shyness and social disinterest [53]. Further, regression analyses demonstrated that the two subtypes of social withdrawal exhibit different patterns of associations with measures of child temperament, observations of free-play behaviors, preschool adjustment, perceived competence, and parenting [53]. For the purpose of this study, only the shyness subscale was used, which is made up of seven items designed to asses social fear and anxiety despite a desire to interact socially. Coefficient α for the primary parent-reported shyness scale in our sample was .90.

Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ)

The BIQ assesses the frequency of children’s behavioral inhibition across three domains: social novelty, situational novelty, and physical activities with possible risk of injury [41]. Items are rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (hardly ever) to 7 (almost always). A parent report form, consisting of 30 items, was completed by the primary parent (N = 488). The BIQ has been shown to have acceptable internal consistency (with just one exception, coefficient alphas exceeded .80 for all six factors scores for all informants), moderate stability over one year (stability coefficients ranged from .49 to .78), strong concurrent validity (the BIQ correlated significantly with the inhibition subscale of the Temperament Assessment Battery for Children-Revised (TABC-R) [54], and construct validity (the BIQ correlated with independent observers’ ratings from video-recorded interactions) [41]. For the present study, we report data from the inhibition with peers scale (6 items), the inhibition with adults scale (4 items), and the inhibition in performance situations scale (4 items) to assess social BI, and the inhibition in physical challenge situations scale (4 items) to assess non-social BI. Coefficient α for the primary parents’ reports of inhibition with peers, inhibition with adults, inhibition in performance situations, and inhibition in physical challenge situations scales in our sample was .92, .91, .84, .74, respectively.

Diagnostic Interview

Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA)

The PAPA is a semi-structured interview designed to assess caregiver reports of psychopathology in preschoolers between two- and five-years-old [55]. The PAPA covers a comprehensive set of symptoms from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; 56) as well as developmentally relevant items, such as eating, sleep, and play behaviors, that are not in the nosology. Adequate test-retest reliability has been reported for the PAPA (median Kappa for diagnoses = .60, range = .36–.87; median ICC for dimensional symptom scores = .66, range = .56–.80) [57]. Interviews were conducted by graduate students in clinical psychology who were trained on the administration by a member of the PAPA development team. Interviews typically lasted between one and two hours and were conducted over the telephone with the primary parent (N = 541). To examine interrator reliability, a second rater from the pool of interviewers independently rated audiotapes of 21 PAPA interviews. The interviews were randomly selected, but we over-sampled participants who reported that their child exhibited significant symptomatology. Two-way random, absolute agreement interrater ICCs were calculated for the dimensional scales [52]. For the purpose of the present study, we report data from the dimensional scales for the three most prevalent anxiety disorders in preschool age children: specific phobia (α = .63, ICC = .97), social phobia (α = .87, ICC = 1.00), and separation anxiety (α = .62, ICC = .98) [58]. Although uncommon in preschool-age children [58], we also report data for symptoms of two other internalizing disorders: depression (α = .75, ICC = .85) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (α = .43, ICC = .94). The scales were constructed by summing the ratings for the items assessed for each disorder. For the specific phobia scale, we excluded fear and avoidance of doctors and clowns as these could be construed as social stimuli. While we hypothesized that the social phobia scale would be associated with social BI and the specific phobia scale would be associated with non-social BI, we did not have any specific hypotheses for the separation anxiety, depression, and GAD scales.

Results

A square root transformation was applied to both the laboratory non-social BI and social BI scales and to the parent-reported shyness scale of the CSPS and parent-reported inhibition with peers, adults, performance situations and physical challenges scales of the BIQ in order to reduce skew. Since the PAPA is a measure of psychiatric symptoms, these scales should not be normally distributed, hence transformation were not applied. Children for whom each of the dependent measures were and were not available did not differ significantly on indices of social and non-social BI. As The relations between laboratory ratings of social and non-social BI with parent-report measures of temperament and anxiety symptoms were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The difference between correlations was tested using Williams’ test [59]. In addition, we conducted multiple linear regression analyses in which social and non-social BI were entered simultaneously in models predicting each of the dependent variables. As the results were similar to the correlations, we present them in Table 2 but do not comment on them further1.

Table 2.

Results of Simultaneous Multiple Regression Analyeses Regressing Temperament and Internalizing Symptoms on Social BI and Non-social BI

| Criterion Variable | N | Social BI | Non-social BI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (β) | (SE) | (t) | (β) | (SE) | (t) | ||

| CBQ Fear- parent | 516 | .74 | .25 | 2.94*** | 1.40 | .23 | 6.10*** |

| CBQ Fear-co- parent | 395 | .30 | .26 | 1.26 | 1.01 | .24 | 4.24*** |

| CBQ Shyness- parent | 519 | 2.83 | .32 | 8.89*** | .74 | .29 | 2.54** |

| CBQ Shyness- co-parent | 394 | 2.19 | .33 | 6.58*** | .58 | .31 | 1.88 |

| CSPS Shyness-parent | 485 | .436 | .08 | 5.41*** | .09 | .07 | 1.29 |

| BIQ Peer | 488 | 1.60 | .27 | 5.88*** | .41 | .25 | 1.64 |

| BIQ Performance Situations | 488 | 1.05 | .21 | 4.90*** | .22 | .20 | 1.11 |

| BIQ Adults | 488 | 2.38 | .22 | 10.59*** | .50 | .20 | 2.45* |

| BIQ Physical Challenge | 488 | .78 | .19 | 4.21*** | .87 | .17 | 5.18*** |

| PAPA Social Phobia | 533 | 2.38 | .54 | 4.39*** | .44 | .51 | .87 |

| PAPA Specific Phobia | 533 | 1.18 | .72 | 2.24* | 1.50 | .67 | 1.64 |

| PAPA Separation Anxiety | 533 | 1.86 | .96 | 1.93* | .94 | .90 | 1.05 |

| PAPA Depression | 533 | 3.66 | 3.03 | 1.96 | 2.78 | 2.83 | 1.05 |

| PAPA GAD | 533 | −3.15 | 16.09 | −.20 | 20.35 | 15.03 | 1.35 |

= p ≤ .05;

= p ≤ .01;

= p ≤ .001;

Note: CBQ = Children’s Behavior Questionnaire; CSPS = Child Social Preference Scale; BIQ = Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire; PAPA = Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment.

The Lab-TAB indices of social and non-social BI were not significantly correlated (r = .07, p = .08). This suggests that they tap distinct constructs.

Temperament

Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ)

As shown in Table 1, parent-reported fear was significantly correlated with both social BI and non-social BI. However, the magnitude of the correlation between parent-reported fear and non-social BI was significantly larger than the correlation between fear and social BI. With regard to co-parent ratings, only the correlation between fear and non-social BI was significant, and the difference between the two correlations was significant.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations of Social BI and Non-social BI with Temperament and Internalizing Symptoms

| Criterion Variable | N | Mean | SD | Social BI (r) | Non- social BI (r) | r difference (t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBQ Fear- parent | 516 | 3.98 | .94 | .14** | .26** | −2.00* |

| CBQ Fear- co-parent | 395 | 3.77 | .83 | .06 | .20** | −2.02* |

| CBQ Shyness- parent | 519 | 3.51 | 1.24 | .37** | .12** | 4.46*** |

| CBQ Shyness- co-parent | 394 | 3.33 | 1.08 | .32** | .09 | 3.43*** |

| CSPS Shyness- parent | 485 | 1.38 | .29 | .24** | .06 | 2.94** |

| BIQ Peer | 488 | 4.07 | .97 | .26** | .08 | 3.00** |

| BIQ Performance Situations | 488 | 3.37 | .78 | .22** | .06 | 2.66** |

| BIQ Adults | 488 | 3.74 | .86 | .44** | .12* | 5.60*** |

| BIQ Physical Challenge | 488 | 3.01 | .67 | .20** | .24** | −.62 |

| PAPA Social Phobia | 533 | .69 | 2.03 | .19** | .05 | 2.46** |

| PAPA Specific Phobia | 533 | 1.81 | 2.65 | .08 | .11* | −.44 |

| PAPA Separation Anxiety | 533 | 3.02 | 3.59 | .09* | .06 | .44 |

| PAPA Depression | 533 | 3.67 | 4.24 | .06 | .04 | .22 |

| PAPA GAD1 | 533 | 63.19 | 58.86 | .00 | .06 | −.98 |

= p ≤ .05;

= p ≤ .01;

= p ≤ .001;

Note: CBQ = Children’s Behavior Questionnaire; CSPS = Child Social Preference Scale; BIQ = Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire; PAPA = Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment;

The mean and standard deviation for the PAPA GAD scale are large because the scale consists of behavioral frequency items.

Similar to parent-reported fear, parent-reported shyness was significantly correlated with both social BI and non-social BI. However, the magnitude of the correlation between parent-reported shyness and social BI was significantly larger than the correlation between non-social BI and parent-reported shyness. Co-parent-reported shyness was significantly correlated only with social BI and the difference between correlations was significant.

Child Social Preferences Scale (CSPS)-Shyness Subscale

Parent-reported shyness was significantly correlated only with social BI and the difference between the correlations was significant.

Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ)

Parent-reported inhibition with peers and inhibition in performance situations were significantly correlated only with social BI and the magnitude of these correlations were significantly greater than the correlations with non-social BI. Parent-reported inhibition with adults was significantly correlated with both social BI and non-social BI. However, the magnitude of the correlation between parent-reported inhibition with adults and social BI was significantly larger than the correlation between parent-reported inhibition with adults and non-social BI. Lastly, parent-reported inhibition in physical challenge situations was significantly correlated with both social BI and non-social BI. There was no significant difference between the coefficients.

Internalizing Symptoms

Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA)

The social phobia scale was significantly correlated only with social BI and the magnitude of the correlation was significantly larger than the correlation with non-social BI. The specific phobia scale was significantly correlated only with non-social BI. However, the difference between the magnitudes of the correlations with social and non-social BI was not significant. Lastly, the separation anxiety scale was significantly correlated with social BI, but the difference between the magnitudes of the correlations with social and non-social BI was not significant. Neither the depression scale nor the GAD scale were significantly associated with social and non-social BI.

Gender Effects

Independent groups t-tests were performed to compare the mean levels of social and non-social BI for males and females. Females exhibited slightly, but significantly, higher levels of social BI (males M = 1.62, SD = .16; females M = 1.64, SD = .16, t (549) = −2.13, p = .03). Similarly, females also exhibited a slightly, but significantly, higher level of non-social BI (males M = 1.33, SD = .16; females M = 1.38, SD = .18, t (557) = −3.35, p = .001).

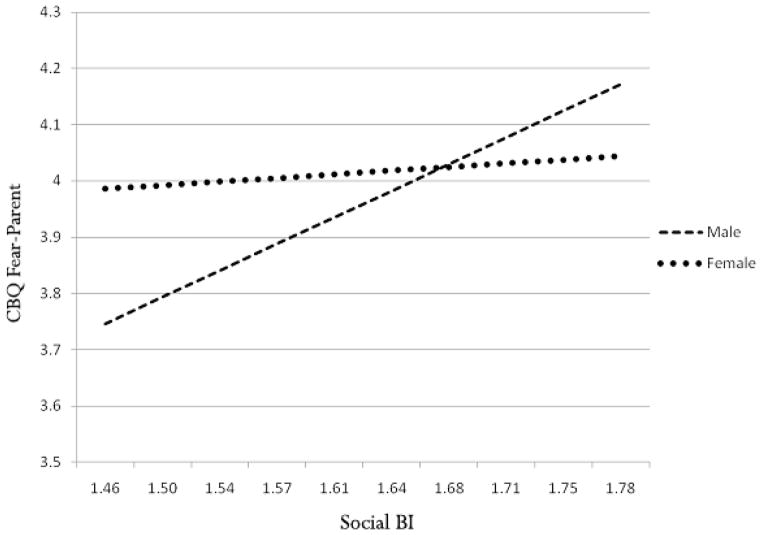

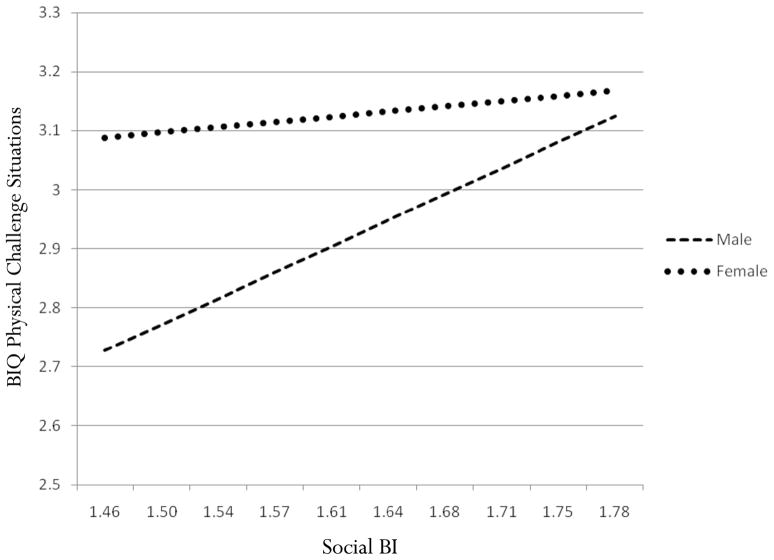

Next, we determined if sex moderated the relationship between social and non-social BI and the temperament and internalizing symptoms. We examined 14 hierarchical multiple regression models, one for each of the temperament and internalizing symptom variables. Social BI, non-social BI, and sex were entered into step one. In step two, the interactions of sex with social BI and sex with non-social BI were entered into the model. Finally, in step three, the three-way interaction between sex, social BI, and nonsocial BI was entered into the model. None of the three-way interactions were significant in any of the models. Two models revealed significant interactions between sex and social BI: CBQ parent-reported fear (β = −.09, SE = .47, t = −2.22, p = .03) and BIQ parent-reported inhibition with physical challenge situations (β = −1.01, SE = .37, t = −1.02, p = .001). Social BI was associated with CBQ parent-reported fear for males (b = 1.33, t = 3.68, p = .001) but not females (b =.18, t = .49, p =.63) (see Figure 1). Similarly, social BI was associated with BIQ parent-reported inhibition with physical challenge situations in males (b = 1.24, t = 4.93, p = .001), but not females (b =.25, t = .89, p =.38) (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Interaction between sex and social BI in predicting CBQ fear-parent.

Figure 2.

Interaction between sex and social BI in predicting BIQ physical challenge situations.

Discussion

BI is usually assessed by combining ratings of fear, vigilance, and avoidance to both novel social stimuli and non-social stimuli, under the assumption that it is a unitary construct. However, this claim has been largely unexamined, except for a few studies that have suggested that BI in social contexts is not correlated with BI in non-social contexts [24, 39, 40]. The present study sought to extend this literature by examining whether social and non-social BI have different parent-reported temperamental and psychopathological correlates.

Our results were consistent with past studies in indicating that laboratory indices of social and non-social BI were not significantly associated. Moreover, we extended this work by demonstrating that these two forms of BI had different temperamental and psychopathological correlates. Laboratory-assessed social BI was associated with parent-reported shyness on the CBQ and CSPS; parent-reported inhibition with peers, adults, and in performance situations on the BIQ; and the social phobia and separation anxiety scales of the PAPA. In contrast, laboratory-assessed non-social BI was associated with parent-reported fear on the CBQ and the specific phobia scale of the PAPA. In most cases, the magnitude of the correlations with social versus non-social BI differed significantly in the predicted direction.

One of the few findings that failed to confirm our hypotheses was that both social and non-social BI were significantly associated with parent-reported inhibition in physical challenge contexts on the BIQ. This lack of specificity may be due to the fact that some of the physical challenge situations reported by the parents may have occurred in social contexts, such as the playground. As anticipated, neither the PAPA depression nor GAD scales were associated with social and non-social BI. Neither of these disorders have been consistently associated with BI as a whole [37], although it is also possible that we could not detect relationships due to the low prevalence of these disorders in preschool-age children.

We found that females demonstrated slightly higher levels of both social and non-social BI than males. Additionally, we examined whether sex moderated the relationship between social and non-social BI and the temperament and internalizing symptoms. None of the three-way interactions between sex and social and non-social BI were significant. However, we found significant two-way interactions between sex and social BI on CBQ parent-reported fear and BIQ parent-reported inhibition in physical challenge situations. In both cases, there were significant associations between social BI and the parent-reported temperament variables among boys, but not among girls. As the CBQ fear and BIQ physical challenge scales primarily consist of non-social content, this suggests that the distinction between social and non-social BI may be clearer in girls than boys. However, these findings should be regarded cautiously, as only two of the 42 interaction terms tested were significant, raising the possibility that they may be the result of Type 1 error.

Recent research has indicated the importance of parsing other temperament variables into finer grained constructs, such as distinguishing between agentic and affiliative positive emotionality/extraversion [60] and approach and withdrawal forms of negative emotionality [61]. Similarly, this study adds to the few previous studies suggesting that BI is a complex construct that consists of at least two distinct forms, social and non-social. Moreover, our findings coincide with research on anxiety disorders demonstrating distinctions between social and non-social fear and anxiety at the phenotypic [42], genotypic [e.g., 44], and neurobiological [e.g., 47] levels. This study extends the literature by demonstrating that these two forms of BI are not only independent but also display distinct correlates with parent reports’ of temperament and anxiety symptoms.

Previous studies examining the normative development of fear in children have indicated that many specific fears (e.g., fear of animals) decline with age, whereas social fears increase as children get older [62]. If the same pattern exists for social and non-social BI, it might account for the moderate stability of overall BI over time, and suggests that these two types of BI may exhibit different developmental trajectories. Furthermore, the distinction between these two types of BI may have important implications for early intervention and treatment. Compared to children who exhibit high levels of non-social BI, it is conjectured that children who exhibit high levels of social BI are more likely to experience greater difficulties in peer interactions, peer relationships, and academic and school adjustment [7]. Long-term costs associated with social BI may also include a greater risk for developing internalizaing problems, including loneliness, low self-esteem, and social anxiety and depressive disorders [7]. Given these risks, children with social BI might be more appropriate targets for early identification and intervention [63, 64]. In contrast, the impact of non-social BI may be more circumscribed and limited to only those situations where the feared stimulus is present (e.g., dog, playground) and may be less like to presage other clinical disorders beyond specific phobia. Moreover, the types of interventions for these two forms of BI should be different. Children with social BI may benefit from cognitive-behavioral programs that are individually tailored to the child’s needs and incorporate such techniques as modeling, exposure, contingency management, coping skills training, and social skills training in order to increase the child’s communication skills, social functioning, and coping skills [7, 63]. In contrast, children with non-social BI may require a less comprehensive intervention package, which might primarily utilize exposure-based strategies to help the child learn how to control or decrease his or her inhibition to the feared stimulus or context through increased contact [7, 63].

This study had several significant strengths. We used a large community sample and multiple assessment methods, including well-controlled laboratory measures of temperament, parent-report measures of temperament, and a diagnostic interview for psychopathology. However, this study also had several limitations that are important to consider. First, the internal consistency of our social BI variable was lower than optimal. Thus, it is conceivable that social BI may itself be heterogeneous. However, we believe that it is more likely that the modest alpha is attributable to the fact that the variable is based on a single episode consisting of 7 items. Unfortunately, we were unable to improve the internal consistency by dropping any of the indicators. Nontheless, it is noteworthy that despite its less than desirable internal consistency, social BI was significantly associated with all of the variables that we predicted it would be. Given the modest internal consistency of the social BI measure, it is likely that we have underestimated the strength of its association with measures of temperament and anxiety symptoms. Second, although we included parent-report measures of temperament and psychopathology, naturalistic observations in the home or school setting could make our findings more ecologically valid. Third, this study was cross-sectional. Future studies should examine the long-term trajectories of social and non-social BI in order to explore differences in developmental outcomes such as risk for psychopathology. Fourth, the participants in this sample were predominantly Caucasian and middle class. Although this limits the generalizability of our findings, it is representative of the population in our geographic region. Fifth, we examined a limited number of external validators to distinguish these two forms of BI. Future studies should attempt to determine whether social and non-social BI have differential associations with familial risk for psychopathology, relevant genetic and neurobiological correlates, and stress reactivity in social and non-social contexts. Finally, in future studies, it may be useful to extend our variable-centered analyses to person-centered analyses that explore the heterogeneity of BI using techniques such as cluster analysis, latent class analysis, and growth mixture modeling.

Summary

In conclusion, the present study examined the distinction between social and non-social BI in a community sample of preschool-age children utilizing a laboratory assessment of child temperament, a diagnostic interview, and parent-completed questionnaires. Results indicate that social and non-social BI are relatively independent and have distinct correlates. Thus, future research should consider treating them as different constructs. This may reduce the heterogeneity of developmental trajectories and outcomes exhibited by high BI children.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health grant R01 MH069942 to Daniel N. Klein and a GCRC Grant no. M01-RR10710 to Stony Brook University from the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

We also ran the analyses controlling for a continuous measure of age. The results were very similar to those reported above and did not change the conclusions.

References

- 1.Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, Garcia-Coll C. Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Dev. 1984;55:2212–222. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kagan J. The concept of behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. In: Reznick JS, editor. Perspectives on behavioral inhibition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1989. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kagan J, Reznick JS, Gibbons J. Inhibited and uninhibted types of children. Child Dev. 1989;60:838–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science. 1988;240:167–171. doi: 10.1126/science.3353713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith HH, Lemery KS. Linking temperamental fearfulness and anxiety symptoms: A behavior-genetic perspective. Bio Psychiatry. 2000;48:1199–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Dev. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annu Rev of Psychol. 2009;60:141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asendorpf JB. Development of inhibited children’s coping with unfamiliarity. Child Dev. 1991;62:1460–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coplan RJ, Rubin KH, Fox NA, Calkins SD, Stewart SL. Being alone, playing alone, and acting alone: Distinguishing among reticence, and passive-, and active-solitude in young children. Child Dev. 1994;65:359–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazelle H, Rudolph KD. Moving toward and away from the world: social approach and avoidance trajectories in anxious solitary youth. Child Dev. 2004;75:829–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asendorpf JB. Beyond social withdrawal: Shyness, unsociability, and peer avoidance. Hum Dev. 1990;33:250–259. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broberg A, Lamb M, Hwang P. Its stability and correlates in sixteen- to forty-month-old children. Child Dev. 1990;61:1153–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr M, Lambert WW, Stattin H, Klackenberg-Larsson I. Stability of inhibition in a Swedish longitudinal sample. Child Dev. 1994;65:138–146. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fordham K, Stevenson-Hinde J. Shyness, friendship quality, and adjustment during middle childhood. J Child Psychol and Psychiatry. 1999;40:757–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanson A, Pedlow R, Cann W, Prior M, Oberklaid F. Shyness ratings: stability and correlates in early childhood. Inter J of Behav Dev. 1996;19:705–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scarpa A, Raine A, Venables P, Mednick S. The stability of inhibited/uninhibited temperament from ages 3 to 11 years in Mauritian children. J Abnor Child Psychol. 1995;23:607–618. doi: 10.1007/BF01447665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhengyan W, Huichang C, Xinyin C. The stability of children’s behavioral inhibition: A longitudinal study from two to four years of age. Acta Pschologia Sinica. 2003;35:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin K, Calkins SD, Schmidt LA. Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Dev. 2001;72:1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfiefer M, Goldsmith HH, Davidson RJ, Rickman M. Continuity and change in inhibited and uninhibited children. Child Dev. 2002;73:1474–1485. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Battaglia M, Bajo S, Strambi LF, Castronovo C, Vanni G, Bellodi L. Physiological and behavioral responses to minor stressors in offspring of patients with panic disorder. J Psych Res. 1997;31:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manassis K, Bradley S, Goldberg S, Hood J, Swinson R. Behavioral inhibition, attachment and anxiety in children of mothers with anxiety disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 1995;40:87–92. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Gersten M, Hirschfeld DR, Meminger SR, Herman JB, et al. Behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and agoraphobia: A controlled study. Arch Gener Psychiatry. 1988;45:463–470. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800290083010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Kagan J, Snidman N, Friedman D, et al. A controlled study of behavioral inhibition in children of parents with panic disorder and depression. Amer J Psychiatry. 2000;157:2002–2010. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kochanska G. Patterns of inhibition to the unfamiliar in children of normal and affectively ill mothers. Child Dev. 1991;62:250–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kochanska G, Radke-Yarrow M. Inhibition in toddlerhood and the dynamics of the child’s interaction with an unfamiliar peer at age five. Child Dev. 1992;63:325–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Hirshfeld DR, Faraone SV, Bolduc EA, Gersten M, et al. Psychiatric correlates of behavioral inhibition in young children of parents with and without psychiatric disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:21–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810130023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, Kagan J. A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. J Amer Acad of Child Adoles Psychiatry. 1993;32:814–821. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc EA, Faraone SV, Snidman N, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of Amer Acad of Child and Adoles Psychiatry. 1992;31:103–111. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, Rosenbaum JF. Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor middle childhood social anxiety: A five-year follow-up. J Dev & Behav Pedia. 2007;28:225–233. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, et al. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. J Amer Acad Child Adoles Psychol. 2009;48:928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayward C, Killen J, Kraemer K, Taylor C. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. J AmerAcad Child Adoles Psychiatry. 1998;37:1308–16. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muris P, Merckelbach H, Wessel I, van de Ven M. Psychopathological correlates of self-reported behavioural inhibition in normal children. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:575–584. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz C, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. J Ameri Acad of Child Adoles Psychiatry. 1999;38:1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Brakel A, Muris P, Bögels S, Thomassen C. A multifactorial model for the etiology of anxiety in non-clinical adolescents: Main and interactive effects of behavioral inhibition, attachment and parental rearing. J Child Fam Studies. 2006;15:568–578. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? J Amer Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2000;39:461–468. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caspi A, Moffit TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence form a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirschfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, Bloomfield A, Biederman J, Rosenbaum J. Behavioral inhibition. Dep Anx. 2008;25:357–367. doi: 10.1002/da.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durbin CE, Klein DN, Hayden EP, Buckley ME, Moerk KC. Temperamental Emotionality in Preschoolers and Parental Mood Disorders. J Abnor. 2005;114:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majdandzic M, van den Boom D. Multimethod longitudinal assessment of temperament in early childhood. J Pers. 2007;75:121–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin KH, Hastings PD, Stewart SL, Henderson HA, Chen X. The consistency and concomitants of inhibition: Some of the children, all of the time. Child Dev. 1997;68:467–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bishop G, Spence SH, MacDonald C. Can parents and teachers provide a reliable and valid report of behavioral inhibition? Child Dev. 2003;74:1899–1917. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spence SH, Rapee R, McDonald C, Ingram M. The structure of anxiety symptoms among preschoolers. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:1293–1316. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eley TC, Bolton D, O’Connor TG, Perrin S, Smith P, Smith P, Plomin R. A twin study of anxiety-related behaviors in pre-school children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:945–960. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eley TC, Rijsdijk FV, Perrin S, O’Connor TG, Bolton D. A multivariate genetic analysis of specific phobia, separation anxiety, and social phobia in early childhood. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;10:839–848. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silberg JL, Rutter M, Eaves L. Genetic and environmental influences on the temporal association between earlier anxiety and later depression in girls. Bio Psychiatry. 2001;49:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Dev. 1987;58:1459–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldin PR, Manber T, Hakimi S, Canli T, Gross JJ. Neural bases of social anxiety disorder: Emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation during social and physical threat. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:170–180. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright CI, Martis B, McMullen K, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Amygdala and insular responses to emotionally valenced human faces in small animal specific phobia. Bio Psychiatry. 2003;54:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Unpublished manuscript 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 3. Circle Pines, Minnesota: American Guidance Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lermery KS, Longley S, Prescott A. Unpublished manuscript. 1995. Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery: Preschool Version. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coplan RJ, Prakash K, O’Neil K, Armer M. Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:244–258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Presley R, Martin RP. Toward a structure of preschool temperament: Factor structure of the Temperament Assessment Battery for Children. J Pers. 1994;62:415–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Egger HL, Ascher BH, Angold A. Unpublished manuscript. 1999. The Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) [Google Scholar]

- 56.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter BK, Angold A. Test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) J Amer Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2006;45:538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Egger A, Angold HL. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:313–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams EJ. The comparison of regression variables. J Royal Statis Soc. 1959;21:396–399. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behav Brain Sci. 1999;22:491–569. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carver CS. Negative affects deriving from the behavioral approach system. Emotion. 2004;4:3–22. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gullone E, King NJ. The fears of youth in the 1990s: Contemporary normative data. J Gene Psychol. 1993;154:137–153. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1993.9914728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J. Rationale and principles for early intervention with young children at risk for anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002;5:161–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1019687531040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rapee RM, Kennedy S, Ingram M, Edwards S, Sweeney L. Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:488–497. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]