Summary

HIV infection is the most devastating infection that has emerged in the recent history. The risk of being infected can be associated with both individual’s knowledge and behavior and community vulnerability influenced by cultural norms, laws, politics, and social practices. Despite that the countries in the Middle East and North Africa have succeeded in keeping low the HIV epidemic rates, the number of identified infected cases are increasing. Since the appearance of the first AIDS cases, all the national authorities devoted their efforts to abort the epidemic in its early stages. The rate of new HIV infections across the Middle East and North Africa region are not at an alarming level, but the need for a concerted effort from nation-states and nongovernmental organizations to stem the spread of the virus across the region is vital.

Most countries of the region have put in place better information systems to track the HIV epidemic, yet the passive HIV/AIDS reporting remains the cornerstone in the HIV surveillance systems. Several countries still believe that their current strategies are optimal to the HIV status within their territories and that their national strategies are appropriate to their low epidemic status that is not expected to grow. Additionally, these countries fear that establishing an HIV national program to survey risk behaviors may be perceived as an approval of these behaviors that are culturally and religiously unacceptable. This background article aims to summarize the HIV surveillance strategies and epidemic profile in 17 Arab countries in the Middle East and North Africa. The article, also, displays the national surveillance system and the epidemic profile in Egypt and Lebanon as models for the region. This information aims to provide useful insights that may help the national authorities in finding out the best surveillance strategies that allow merging and collecting biological and risk data which is an integral part of their efforts to fight the HIV epidemic in the region.

Keywords: HIV, Middle East and North Africa, Surveillance

INTRODUCTION

HIV infection is a lifelong viral infection. Throughout the incubation period, which may extend for 10 years, the virus weakens the immune system of the body, becomes symptomatic, and the patient develops AIDS and a variety of severe AIDS-related illnesses that are the leading causes of death. There is no cure for HIV infection, yet the antiretroviral therapy (ART) can help to slow the replication of the virus in the body which in turn reduces the burden of the virus on the immune system, thereby delaying the HIV-related illnesses and allowing the patient to live longer with higher quality of life. The long incubation period means that few infected people are identified although much more are unperceived and are transmitting the infection silently with more victims affected. The first AIDS case worldwide was declared in 1981, since then the HIV threat started touching one country after the other. The common feature of the HIV infection is that it starts at a very low prevalence rate in a country, then increases dramatically with the explosion of the epidemic in the absence of adequate preventive efforts. This natural progression brought the HIV pandemic on the forefront of the millennium health agenda. Emerging evidence has proved that controlling the HIV spread needs a very rigorous and consistent surveillance system that is more sophisticated than the traditional public health disease surveillance. The specific nature of the HIV epidemic has called for national surveillance system that goes beyond the detection of infected cases to plunge in the inherent root causes and risk behaviors that catalyzes the progression of the epidemic.

It is estimated that there are 380,000 people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).1 Although these constitute a small portion of the 33.2 million PLHA worldwide, yet the number of newly infected cases in the MENA region is increasing. For years, it has been believed that the conservative culture in the MENA countries has helped in speeding down the HIV spread and keeping the rates of HIV infection relatively low. However, this does not mean that the MENA countries are immune against HIV spread.2,3 The diagnosis of the AIDS cases in the region since the mid-1980s and the identification of the multiple routes of transmission have proved that the MENA countries are not off the beaten path of HIV infection.4 It is worth mentioning that from the very beginning, the national authorities devoted their efforts to the prevention of HIV spread in an attempt to abort the epidemic at its early stages. The national Ministries of Health (MOH) took the lead in detecting AIDS cases and monitoring the epidemic. During the early years, the national efforts responded to the need expressed by policy makers to know more about the number of emerging HIV cases and the routes of transmission. Thus, the national efforts focused on strengthening HIV testing laboratory facilities and on training health personnel in detecting AIDS cases. However, later on with the growth of the epidemic and the emerging evidence about the dynamics of HIV spread, these efforts turned out to be insufficient. The need for potent surveillance systems proved indispensable to track the HIV epidemic and provide the necessary information to design and improve prevention, care, and treatment programs in the MENA countries.

In the recent years, the MENA countries have put in place better information systems to track the HIV epidemic.5–7 However, several countries still resist proceeding to the epoch of the second-generation surveillance systems that compile HIV serological and risk data from multiple sources for several reasons. First, several countries still believe that HIV is not a menace to their territories, and their national strategies are appropriate to their low epidemic status that is not expected to grow. Second, the fear that establishing an HIV national program to survey risk behaviors among the high-risk groups may be perceived as an approval or legitimacy of these behaviors; which opposes the cultural and religious beliefs in the MENA countries. Third, the misconception that collecting information on risk behaviors, especially from the youth, is an invitation to encourage risk practices. Fourth, policy makers prefer to save the efforts and resources to the priority health issue on their agenda where HIV gains limited attention. However, these claims need to be weighed against the cost of delayed actions. Experience has proved that delaying efforts to combat the HIV epidemic is a real menace to the health status, social condition, and economic situation within a country. In fact, the HIV epidemic will certainly grow even in low epidemic scenarios if not promptly faced because of the bridge populations. Countries that responded to the HIV epidemic early on were able to control the spread of infection effectively, and the MENA countries still have a window for aborting the epidemic in its early stages.

This background article aims to summarize the HIV surveillance strategies and the HIV epidemic profile in the MENA countries; it attempts to answer 3 questions: (1) are the current surveillance strategies in the MENA countries appropriate to the epidemic status; (2) is there a risk of HIV epidemic growth in the region that calls for more prompt surveillance efforts; and (3) are there any apparent inequities in the HIV epidemic and are there any disadvantaged groups. The responses to these questions provide useful insights that may help the national authorities in their efforts to fight the HIV epidemic in the region.

Section 2 of this article presents the HIV surveillance strategies in the MENA countries and the current HIV epidemic profile in these countries. This section made use of the published Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS/World Health Organization (UNAIDS/WHO) and World Bank reports on 17 Arab countries in the MENA region. Sections 3 and 4 describe case studies in Egypt and Lebanon as model examples in the region. Each case study is divided into 3 sections giving a brief description of the national surveillance system, the first round biological and behavioral surveillance survey (BIO-BSS), and the epidemic profile in each country. The data for Egypt and Lebanon are extracted from the national reports and the results of the various surveys done in the 2 countries. The last Section refers to the lessons learned, barriers to policies, and the way forward.

HIV STATUS IN THE MENA

Published UNAIDS/WHO and World Bank reports on 17 Arab countries in the MENA region have been reviewed. The MENA countries are divided into 4 geographic regions, 2 in the African continent and 2 in the Asian continent. The first African group includes 3 countries in northeast Africa including Egypt, Libya, and Sudan. The second African group includes the countries of the Arab Maghreb present in northwest Africa including Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The first Asian group is located in northwest Asia including Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. The second Asian group in the middle and southwest Asia includes Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. These countries were chosen as they share the same geographic location and cultural norms. In addition, many of their citizens are crossing borders for education, medical care, or business. Most of these countries share common beliefs that HIV spread is limited within their borders and that any infection affects either foreigners living within their boundaries or returning nationals who were infected abroad. Furthermore, these countries have nearly similar HIV epidemic profile, mainly low-grade epidemic, and therefore similar HIV surveillance needs.

HIV Surveillance in the MENA

Since the appearance of the first AIDS cases, the MOH in the 17 MENA countries took the lead to face the epidemic. In most countries, a National AIDS program (NAP) was rooted in the MOH to monitor the epidemic. However, the MOH in Iraq, Libya, Morocco, Qatar, and Syria have a “National Strategic Plan” rather than a NAP to govern the national response to AIDS.

The MENA countries adopted several inconsistent HIV surveillance strategies.8 Nevertheless, all countries directed their efforts on HIV/AIDS case reporting as the surveillance tool. Till the mid-1990s, all countries used an AIDS clinical definition; currently most of the 17 countries relay on the HIV testing results.9,10 Reports are then generated for HIV/AIDS-positive cases including sociodemographic background, possible route of transmission, and the country where the person might have been infected. The national program would then compile and analyze the data to present them to decision makers and report them to the WHO Global Program on HIV/AIDS. The common feature in all countries is the use of a passive surveillance system deriving data from various sources that include blood screening and testing of blood donors, multiple transfused children with haemolytic anaemia, prisoners, symptomatic cases for diagnostic purposes, and sexual partners of HIV-infected cases. Additionally, several countries extend their targets to migrant workers and long-term travelers, and those seeking premarital counseling. Through the passive surveillance system, Libya was able to detect an HIV hospital outbreak among 370 children from lack of infection control, and Egypt reported few HIV outbreaks among kidney renal dialysis patients and transfusion of contaminated blood collected in few private blood banks.11

When the need for active surveillance emerged, several MENA countries have been implementing the sentinel surveillance surveys. However, these surveys are mostly designed for pregnant women attending antenatal clinics.

The second-generation surveillance surveys (Box 1) are not yet established in most MENA countries. Most countries currently depend on HIV/AIDS reporting in addition to sporadic surveys on knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and practices (KABP) among different population subgroups, and they rarely approach the high-risk groups or seek data on risk behaviors.

BOX 1. Second Generation Surveillance Surveys.

Second-generation surveillance for HIV/AIDS is the regular systematic collection analysis and interpretation of information for use in tracking and describing changes in the HIV/AIDS epidemic over time.

Second-generation surveillance for HIV/AIDS also gathers information on risk behaviors, using them to warn of or explain changes in levels of infection.

As such, second-generation surveillance includes, in addition to HIV surveillance and AIDS case reporting, STI surveillance to monitor the spread of STI in populations at risk of HIV and behavioral surveillance to monitor trends in risk behaviors over time.

These different components achieve greater or lesser significance depending on the surveillance needs of a country, determined by the level of the epidemic it is facing: low level, concentrated, or generalized.

Throughout 2000–2002, Kuwait, Libya, and Sudan have undergone nationwide population-based HIV serological surveys. In 2007, Tunisia has updated the national strategic plan to mount the second-generation surveillance surveys on list of activities. Egypt and Lebanon are the most advanced in this respect. Egypt (2006) and Lebanon (2007) implemented the first round BIO-BSS. However, both countries have no clear plans that ensure the repetition of the BIO-BSS rounds as recommended in WHO/UNAIDS guidelines (Box 2).

BOX 2. Target Groups, Type and Frequency of Surveillance by Epidemic Status.

| Stage of the Epidemic | Serosurveillance (Annually if Feasible) |

Behavioral Surveillance |

|---|---|---|

| Low grade: prevalence of HIV is consistently below 5% in any “high-risk groups” and below 1% in the “general population” |

|

|

| Concentrated: prevalence of HIV has surpassed 5% on a consistent basis in one or more “high-risk groups” but remains below 1% in the “general population” |

|

|

| Generalized: prevalence of HIV has surpassed 1% in the “general population” |

|

|

Adapted from Guideline for Second General Surveillance, WHO/UNAIDS.

HIV Epidemic Profile in the MENA

The first AIDS cases in the MENA countries were reported in Kuwait and Lebanon in 1984. This was followed by the appearance of AIDS cases in Bahrain, Algeria, and Tunisia in 1985. In the following year, Egypt, Jordan, and Morocco reported the detection of AIDS cases and were followed by Syria and Oman in 1987. In the remaining countries, AIDS case reporting started later. However, by the dawn of the new millennium, AIDS cases were declared in the 17 countries. This is an indication that HIV infection and transmission in the MENA countries date earlier than national-reported AIDS cases.

The serological data on HIV status are scarce in the region (Table 1). There are no available estimated statistics on PLHA in Libya, Iraq, Syria, and all countries in the middle and southwest Asia. Even the countries with available statistics have limited HIV information. Jordan, Lebanon, Bahrain, and Kuwait do not provide statistics on the age and sex distribution of infected people. Despite that mother-to-child transmission is evident in the national reports, Sudan was the only country to report HIV infection among children younger than 5 years. The weak reporting is due to the limitation in the surveillance systems, the insufficiency in surveillance capacities, and the reluctance of some national authorities to report HIV infections within their territories. In almost all countries, the first years of testing found positive results among foreigners, returning citizens, or those infected through blood and blood products. Nevertheless, the reported statistics represent a relatively cohesive overview of the region. Sudan has the highest estimated number of PLHA in the region with 350,000 infected individuals. The HIV prevalence is increasing steadily among pregnant women and blood donors, indicating the spread of the infection among the general population.12 The HIV epidemic status seems to be alarming in Algeria and Morocco as it is estimated that there are 19,000 infected individuals in each country. From the few HIV statistics available, HIV seems to attack the productive population in the region. Moreover, it is also evident that the epidemic is not only confined to males but also a considerable number of females are estimated to be affected. In Sudan, the share of women seems to be exceeding that of men. The reported number of infected women in the MENA countries disproves the wide spread misconception that HIV infection is a male disease spreading only through the activity of men who have sex with men (MSM).

TABLE 1.

HIV Infection in the 17 Arab Countries in the MENA

| PLHA | Adults (15+) | Children (0–14) | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast Africa | ||||

| Egypt | 5300 (2900–13,000) | 5200 (2800–13,000) | N/A | <1000 (430–2300) |

| Libya | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sudan | 350,000 (170,000–580,000) | 320,000 (160,000–530,000) | 30,000 (12,000–74,000) | 180,000 (80,000–320,000) |

| Arab Maghreb | ||||

| Algeria | 19,000 (9000–59,000) | 19,000 (8800–60,000) | N/A | 4100 (1700–13,000) |

| Morocco | 19,000 (12,000–38,000) | 19,000 (12,000–38,000) | N/A | 4000 (2100–8400) |

| Tunisia | 8700 (4700–21,000) | 8600 (4600–21,000) | N/A | 1900 (860–4700) |

| Northwest Asia | ||||

| Iraq | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Jordan | <1000 (<2000) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Lebanon | 2900 (1400–9200) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Syria | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Middle and Southwest Asia | ||||

| Bahrain | <1000 (<2000) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kuwait | <1000 (<2000) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Oman | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Qatar | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Saudi Arabia | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| UA Emirates | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Yemen | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Adapted from UNAIDS Country Reports Update, 2006.

N/A, not available.

The limited information on the number of PLHA requires additional supportive data to reveal the magnitude of the infection in the MENA countries. This made us turn to the only available complete information on reported AIDS cases in the region (Table 2). According to the available data to the end of 2001, 8793 developed AIDS in the 17 MENA countries. Qatar, Oman, Bahrain, and Sudan stand out clearly as having a heavy epidemic toll. The relatively lower rates in the remaining countries do not mean stable situations as AIDS case reporting is only capable of detecting past patterns but can not predict current or future patterns of transmission. Furthermore, the discovered AIDS cases hide behind them plenty of HIV infections that remain unperceived. Table 2 provides evidence that the MENA countries suffer from HIV infection and transmission for several years.

TABLE 2.

AIDS Status in the 17 Arab Countries in the MENA

| Total Population in 2001 (000) |

Total AIDS Cases up to 2001 |

Rate (per 100,000) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast Africa | |||

| Egypt | 69,080 | 321 | 0.8 |

| Libya | 5471 | 611 | 11.2 |

| Sudan | 31,809 | 3866 | 12.2 |

| Arab Maghreb | |||

| Algeria | 30,841 | 501 | 1.6 |

| Morocco | 30,430 | 969 | 3.2 |

| Tunisia | 9562 | 633 | 6.6 |

| Northwest Asia | |||

| Iraq | 23,584 | 124 | 0.5 |

| Jordan | 5051 | 98 | 1.9 |

| Lebanon | 3556 | 218 | 6.1 |

| Syria | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Middle and Southwest Asia | |||

| Bahrain | 652 | 89 | 13.6 |

| Kuwait | 1971 | 71 | 3.6 |

| Oman | 2622 | 441 | 16.8 |

| Qatar | 575 | 125 | 21.7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 21,028 | 465 | 2.2 |

| UA Emirates | 2398 | 22 | 0.9 |

| Yemen | 19,114 | 239 | 1.3 |

Adapted from Carol Jenkins and Robalino8.

HIV STATUS IN EGYPT

HIV Surveillance in Egypt

Since the detection of the first AIDS case, Egypt Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP) is fully committed to slowdown the spread of the infection and to care for the PLHA. In 1986, under the auspices of the Minister of Health and Population, Egypt established the NAP and the National Committee for Combating AIDS as one of the preventive diseases programs in the MOHP. The national program at that time set the following strategies to prevent the spread of the infection:

Adding AIDS to the list of diseases that require mandatory reporting to the health authorities.

Forbidding the use of glass syringes and shifting to plastic disposable syringes.

Forbidding the transfusion of blood and blood products except after HIV screening.

HIV testing for all foreigners staying in the country for more than 1 month.

In the late-1980s, all national efforts were directed to passive HIV/AIDS case reporting. Starting from the year 2000 and supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the HIV/AIDS passive surveillance in Egypt matured into well-established functioning system acting on 2 fronts. First, the Epidemiology and Surveillance Unit (ESU) that acts on central, governorate, and district levels to track the incidence and prevalence of HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases. The central level ESU is institutionalized in the MOHP and reports directly to the Minister of Health. Second, the creation of the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System in at least 13 governorates designed to include data on 26 priority infectious diseases that are electronically entered by public hospitals possessing confirmatory laboratory tests, teaching hospitals, health insurance organization, and the private sector. The uploaded data ascends to the district level ESU, then to the governorate level ESU, and finally to the central level ESU where it is analyzed and shared with the concerned departments of the MOHP.13

The NAP developed partnership with other national sectors such as education, information, social solidarity, interior, religious affairs, mass media, nongovernmental organizations, and international agencies. As part of its ongoing support for the MOHP’s HIV prevention activities, the USAID in collaboration with Family Health International (FHI) designed and implemented an HIV/AIDS prevention program appropriate for the stage of the HIV epidemic in the country. As an initial step, a study was conducted in 1999 that aimed to measure the prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among different population subgroups living in greater Cairo. The study, which is considered the first in Egypt targeting high-risk groups, included female sex workers (FSWs), injecting drug users (IDUs), MSM in addition to antenatal care attendees, and family planning clinic attendees, Among the 994 people examined, STIs were detected in 79 respondents.14

The NAP, supported by the Ford Foundation and UNICEF, developed a telephone hotline that receives an average of 35 calls daily. The hotline provides information on HIV/AIDS and sexual health. Since 2004, FHI, USAID, the United Nations Population Fund, and the Italian Cooperation have worked in conjunction with the NAP in establishing 15 fixed and 9 mobile voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) centers that succeeded in attracting 3718 high-risk people till 2007 according to the NAP report in December 2007.

The NAP developed policies and national guidelines, established model sites, and trained medical professionals to build their capacity in various areas of HIV/AIDS prevention and care.15

The persistent NAP efforts evolved to respond to the trends in HIV transmission. The NAP has realized the need for a second-generation surveillance survey even with the low prevalence estimates in the country (0.08 of 1000). Beginning in 2003, the NAP started to address the need for good and reliable data. A National Surveillance Consensus Meeting was conducted by FHI and attended by various partners including NAP, USAID, UNAIDS, Naval Medical Research Unit (NAMRU-3), WHO, and Ford Foundation. As a result, a “National HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance Plan” was developed and agreed upon. The plan aims to restructure the National Surveillance System, inform key stakeholders of the NAP’s surveillance strategy, and allow for ongoing monitoring of the HIV epidemic. One of the challenges identified to implementing a national surveillance system was the lack of trained staff to implement and maintain such an important system. FHI helped to overcome this by building the capacity of NAP staff members through attending behavioral surveillance survey trainings held in Kenya and Ethiopia and the Regional HIV surveillance training held in Egypt.16

The feasibility of the surveillance systems implemented in Egypt and the perceived need to replicate such program in MENA countries urged FHI and WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office to organize 2 regional workshops in Cairo on HIV surveillance and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of HIV/AIDS programs in 2005 and 2006. The 2 workshops hosted NAP managers and respective senior technical officers from 12 countries of the MENA region as a preliminary step to help replication of the program in their respective countries. Additionally, in country visits for provision of technical assistance in the areas of surveillance and M&E were provided by FHI to Libya and Oman, respectively. Furthermore, 2 manuals on the HIV behavioral surveillance survey and M&E of HIV/AIDS programs were translated to Arabic and adapted to the cultural context.17

Egypt First Round BIO-BSS

Despite the NAP’s activities in the area of HIV surveillance, there is still a serious need for data to track the HIV infection trend and risk behaviors among high-risk subpopulations. The HIV/AIDS reporting, the traditional cornerstone of the country’s HIV monitoring efforts, becomes less useful as the epidemic matures. From this analysis emerged a need for the BIO-BSS focusing on most vulnerable and high-risk segments of the population whose behaviors can have the most effect on the course of the epidemic. Egypt MOHP in collaboration with FHI and USAID were pioneers in the region to conduct the first round BIO-BSS. The objectives of the first round BIO-BSS were as follows:

-

Develop a model surveillance system:

To help create human capacity needed to establish and maintain the surveillance system.

To obtain data in a standardized format, which will enable comparison with other behavioral surveillance studies carried out in Egypt and other countries.

To provide information that helps to guide future program planning.

-

Track behavioral data for high-risk groups:

To assess HIV knowledge and beliefs among high-risk groups.

To measure the frequency of risk behavior practices among high-risk groups.

-

Assess biological data for high-risk groups:

To determine the prevalence of HIV among the high-risk groups.

To measure the impact of risk behaviors on exposure to HIV infection.

-

Provide counseling:

To provide members of populations at high risk the opportunity to receive counseling and testing for HIV.

-

Assess effects of previous interventions:

To provide evidence of the relative success of the combination of HIV prevention efforts taking place.

Egypt first round BIO-BSS targeted street children, FSWs, MSM, and IDUs. The planning stage started in 2004 and the actual fieldwork took place in 2006. The FHI-standardized HIV BIO-BSS questionnaires18 were translated into Arabic and adapted to the local context and tailored to different target groups based on results of a proceeding formative assessment. Male IDUs and MSM were interviewed by their peers, whereas Street children, FSWs, and female IDUs were interviewed by the nongovernmental organizations’ (NGOs) social workers. All interviewers and counselors received extensive training before the survey implementation. Technical training workshops on respondent-driven sampling, used for the first time in the MENA region to reach the IDUs and MSM, were conducted.

Egypt experience was a true success in collecting biological data and information on risk practices from the target groups. The respondent-driven sampling helped in reaching the hidden and hard to reach male IDUs and MSM. Egypt BIO-BSS revealed that females in Egypt, whether street girls, FSWs, or female IDUs, are more difficult to reach than males and hardly network with the same sex. This has emerged the need for innovative approaches to reach the female population in the country.19

HIV Epidemic Profile in Egypt

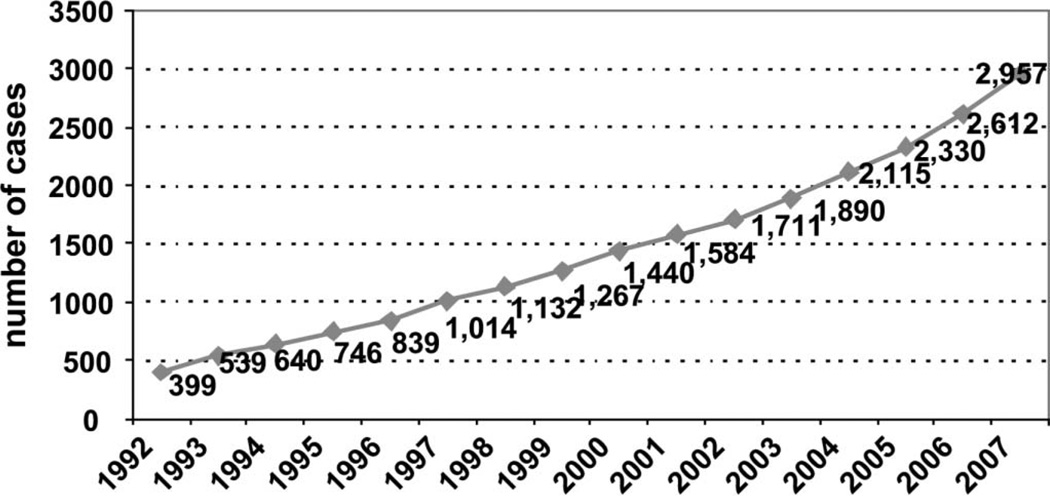

HIV epidemic has never been a health threat in the country, however, there is always fear that the epidemic may grow. Egypt’s first AIDS case was discovered in 1986, since then the number of HIV reported cases are showing a steady increase and are estimated to double nearly every 5 years (Fig. 1). The perceived increase in the number of PLHA in Egypt is mainly due to the persistent efforts of the MOHP to improve HIV/AIDS case reporting. According to the national statistics in December 2007, 2957 HIV-infected cases are identified; from them, 2183 (73.8%) are Egyptians. From the HIV infected Egyptians, 766 (35.1%) developed AIDS and 1028 cases died of AIDS.

FIGURE 1.

Number of HIV reported cases in Egypt. Adapted from Egypt Ministry of Health and Population, Report January 30, 2007 and Report December 31, 2007.

The statistics reported on national level represent around half of the cases estimated by the UNAIDS/WHO Report in 2006. The national statistics on HIV infection are expected to be underestimated because they are based mainly on mandatory testing for HIV, reports of VCT units, and passive surveillance systems.

Till lately, Egypt has been considered an HIV/AIDS low-grade epidemic country. However, of the high-risk individuals tested for HIV between August 2004 and August 2006 at the Central Laboratory VCT Center, 6.4% of males and 14.8% of females tested positive for HIV. Moreover, the first round BIO-BSS has revealed that 0.6% of IDUs, 0.8% of FSWs, and 6.2% of MSM were HIV infected.19 This information is an indication that Egypt is stepping toward a concentrated HIV epidemic.

There is always a myth that HIV infection is limited to a minority with high-risk behaviors who do not have any relations with the general population. It is true that heterosexual transmission, homosexual transmission, and spread of infection through injecting drug represent the main route causes, yet HIV spread is not only limited to these risk behaviors. According to NAP report in December 2007, 6.2% of AIDS reported cases were due to transfusion of blood and blood products, 12.0% due to renal dialysis, and 1.6% due to mother-to-child transmission. Furthermore, the BIO-BSS results have revealed that the target groups practicing risk behaviors have links with the general population as a considerable proportion of them, even the MSM, are either married or have multiple opposite sex partners (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Links Between the Sexually Active Target Groups and the Various Population Categories in Egypt

| Currently Married |

Regular Noncommercial Sex |

Commercial Sex Partners |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Street boys (n = 168) | — | 95.2 | 14.9 |

| Street girls (n = 69) | — | 97.1 | 33.3 |

| FSWs (n = 118) | 37.3 | 60.0 | 100.0 |

| MSM (n = 267) | 5.6 | 80.0 | 42.0 |

| Male IDUs (n = 280) | 57.8 | 88.2 | 13.3 |

Adapted from Egypt Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey, Summary Report 2006.

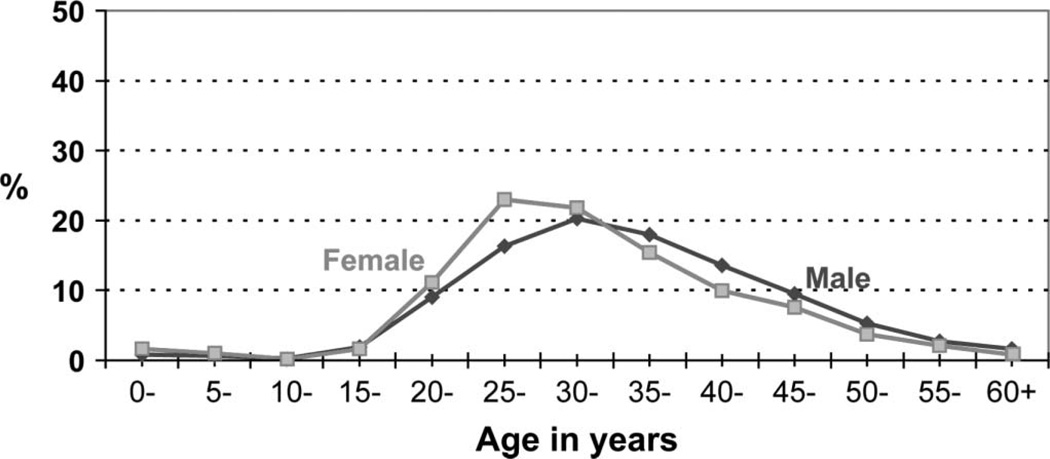

According to the national statistics in 2006, HIV seems to be prevalent among the most productive population in Egypt as 89.0% of the HIV infected are between 15–49 years old. Egypt is experiencing an increase in the number of affected women. The share of females in Egypt represent around one fifth of people living with the HIV infection. It is also important to note that when comparing the males and females living with HIV/AIDS according to the age distribution (Fig. 2), the infection is concentrated in women aged 20–34 years more than men in the same age group and the inverse is seen for older age groups. This is an indication that the majority of females are infected at an earlier age than males.

FIGURE 2.

Age distribution of HIV-infected females and males in Egypt. Adapted from Egypt Ministry of Health and Population, Report January 30, 2007.

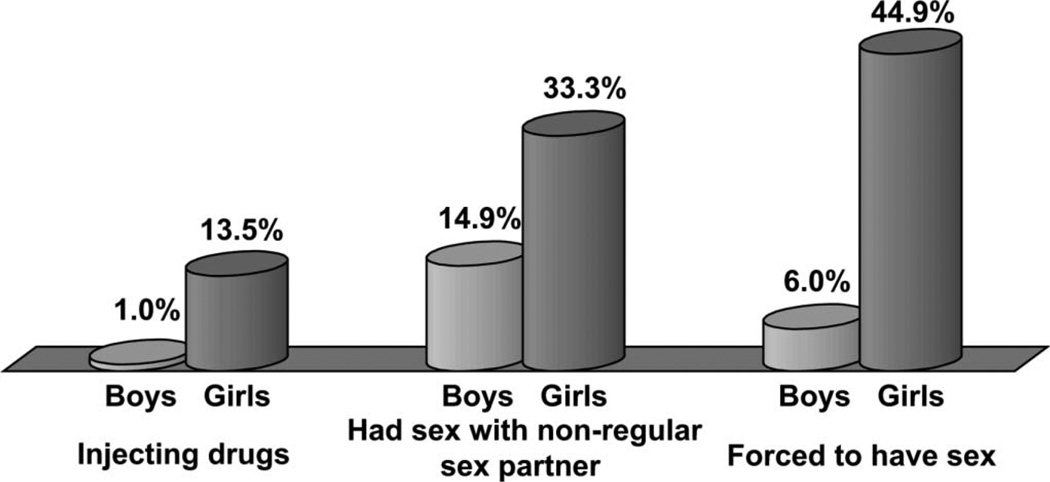

In Egypt, first round BIO-BSS (Fig. 3), despite that street girls were more exposed to risk practices, both boys and girls were injecting drugs, practicing sex with nonregular partners, and forced to have sex.

FIGURE 3.

Risk behaviors among street children in the 12 months before the survey. Adapted from Egypt Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey, Summary Report 2006.

The results of the BIO-BSS have, also, pointed out that condom use among the target groups, whether males or females, is low (Fig. 4). Moreover, the HIV/AIDS comprehensive knowledge is low among members of all groups with numerous misconceptions.

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of condom use as reported by street children, male IDUs, FSWs, and MSM. Adapted from Egypt Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey, Summary Report 2006.

HIV STATUS IN LEBANON

HIV Surveillance in Lebanon

The first case of AIDS in the world was declared in 1981. Few years later, in 1984, the first case was diagnosed in Lebanon. Since then, 1056 PLHA have been reported. However, these figures are likely to be an underestimation because of underreporting for a number of reasons, which include fear of stigmatization, inadequate surveillance systems, and capacity issues. Furthermore, the level of voluntary testing in Lebanon is low, probably due to reluctance to seek testing for fear of stigma and discrimination, because people’s risk perception is low, and because the present cost of testing is high for many people. Moreover, free VCT centers remain a new concept in the country. Thus, the reported cases are drawn mainly from patients presenting with AIDS-related symptoms and from mandatory testing of about-to-wed couples and some immigrants, particularly those who come to Lebanon to work as domestic workers. Also, several private health care providers do not consistently report cases. Many view reporting as an additional workload, and some are not convinced that their patients’ information would be kept confidential if reported to other bodies. Thus, the problems of data collection have lead to uncertainties about the true extent of the epidemic in the country.

The Lebanese government commenced its effort to address HIV/AIDS in the early 1990s when it established the NAP and its committees. Since then, the Government of Lebanon has provided the NAP with the full political and financial support needed to carry out education and awareness activities among the general population and later on expanding into care and support including providing ART to eligible patients. The Government of Lebanon being aware of the growth of the epidemic worldwide despite all the efforts made internationally to curb the epidemic is also acknowledging that HIV/AIDS could emerge as primary threat to the growth and development of Lebanon in few years based on the existence of risk factors for the disease in the country. Taking these into consideration, the Government of Lebanon decided that it was necessary to revisit all the strategies that were previously adopted to address HIV in the country.

By 2002, the NAP has accomplished 7 KABP studies related to HIV and an HIV situation assessment among the high-risk groups. These included surveys of general population (1991), nurses (1993), laboratory personnel (1993), secondary school students (1994), out-of-school youth (1994), military academy (1995), general population evaluation (1996), situation analysis of vulnerable groups (2002), and KABP Study (2004).20 These studies were useful to define the weakness areas in the knowledge and practices and to plan activities accordingly. Of each KABP, 500 copies (Arabic, English) were printed and distributed to universities, ministries, NGOs, and other stakeholders.

Furthermore, in June 2003, the NAP, in coordination with the civil society, NGOs, multisectoral ministries, United Nations Agencies (including the World Bank), activists, and other stakeholders gathered at a 1-week national workshop to develop a national strategic plan to fight HIV that incorporates new modalities of approaches to address the disease. The end of this consultative exercise is the HIV National Strategic Plan for 2004–2009. The 4 guiding principles of this strategic plan focus on (1) Advocacy, human rights, and coordination; (2) Prevention; (3) Treatment, care, and support; and (4) Monitoring, surveillance, and evaluation.

Within the context of those guiding principles, 12 goals were adopted, which in turn were divided into activities that will govern the plans of the NAP until 2009. With the assistance and collaboration of the United Nations Theme Group members and UNAIDS, an operational plan was subsequently developed by the NAP with the intention of implementing the series of activities according to priorities and the availability of funds and human capacity.

Among the highest priority areas within the national strategic plan is monitoring surveillance and evaluation. Within this priority area, 2 specific goals were identified as follows: (1) to develop a comprehensive and integrated monitoring, surveillance, and evaluation system; and (2) improve surveillance and reporting activities. The achievement of these 2 goals would provide the country with reliable and accurate data to be able to assess the socioeconomic impact of HIV/AIDS on the country and improve the countries capacity to plan and implement comprehensive HIV/AIDS prevention and mitigation interventions.

In 2005, with the support of the World Bank, a M&E operational plan was developed. Today, the NAP is responsible for the M&E of the disease progress and has performed an important work. The NAP is responsible for collecting data reported by physicians, laboratories, and blood banks. The data analyses and projections are performed and reported periodically. Estimations on the number of PLHA in Lebanon are made based on a model developed by UNAIDS and WHO. The reporting forms were revised and modified to include a follow-up. A complete and integrated surveillance and monitoring system of HIV in Lebanon had therefore, been developed. Specifically, the monitoring consists of observing on a regular basis the priority information and the results related to the programs fighting HIV. The interpretation, combined with data coming from different sources, represents a key element for an effective follow-up system. Monitoring indicators represent vital signs of the HIV epidemic at the country level because they describe the state of the epidemic, its propagation factors, and the importance of the different response efforts. They allow program managers to pinpoint the areas to be reinforced and to highlight questions that could contribute to an improvement in the response. The M&E system helps to establish performance incentives for program implementers; detect and address problems on time; provide early evidence of program effectiveness; and communicate to those infected and affected the efforts being made to improve prevention, care, treatment, and mitigation programs.

The M&E (epidemiologic and programmatic) system is a source of information performance for the public and for donors and to be a management tool for implementation agencies in the public and private sector, in civil society, and for country coordination mechanisms. The M&E system enhances the capacity of the Government of Lebanon to plan, manage, and implement HIV/AIDS prevention, care and treatment, and mitigation programs in the country. M&E is a core part of the fiduciary architecture of financial management, disbursement, and procurement, which is the basis for the performance contract on which the war against HIV/AIDS is being waged.21

However, even with the existence of an M&E system, the data on the epidemic in the country remained inadequate; it was important that the national surveillance system be strengthened to provide better data for M&E of HIV programs. Because the epidemic in Lebanon is still largely confined to vulnerable groups, it is important to particularly strengthen surveillance methods targeted at these groups. In the effort to strengthen and upgrade the current surveillance system into a second-generation surveillance system that is more efficient in tracking the epidemic, in 2006, the NAP evaluated its system by assessing the existing processes of data collection; identifying gaps; recommending processes for upgrading to a second-generation system; developing an operational manual; and training of staff on the process for implementing the upgraded system and implementing 4 studies targeting the most at-risk populations: IDUs, SWs, MSMs, and prisoners.

Lebanon First Round BIO-BSS

The level of the epidemic in Lebanon is currently low, with an estimated adult prevalence rate of 0.1%.22 However, there are several reasons to be concerned about HIV in Lebanon. First, there is a high level of interaction between Lebanese and nationals of other countries, and evidence that increasingly infection is occurring within Lebanon among individuals who have not traveled outside the country. Second, there is evidence of increasing rates of unprotected sex among young people, and the median age at infection is decreasing. These factors called for improved surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation to track HIV trends and to intervene early and effectively.

The deepened knowledge of the nature of the epidemic is essential. It is thus imperative to obtain more data on the persons who are at higher risk and on the risk-promoting behaviors. Good quality behavioral data allow following up the risky populations and help target HIV surveillance resources where they would provide maximum information on the epidemic evolution. Until recently, there were a number of limitations in the existing methods for assessing the level and dynamics of the epidemic in Lebanon. As mentioned above, Lebanon relied upon case reporting and estimation for its HIV data and had no HIV biological surveys whatsoever. It is vital to establish HIV and related behavioral trends among vulnerable groups in low prevalence epidemics, to develop informed evidence-based HIV responses, in which priorities are based on objective biological and behavioral data. Lebanon’s HIV resources are extremely limited and must be directed toward the most vulnerable communities and cost-effective interventions. In the absence of biobehavioral surveillance, it would be impossible for Lebanon to program rationally, to identify risk, to track trends, or to assess progress. Thus, biobehavioral surveys underpin the entire HIV strategy and M&E framework.

In November 2007, Lebanon urgently required a greater understanding of its epidemic, and high quality-integrated biobehavioral surveys of vulnerable populations are a prerequisite for greater understanding of low prevalence epidemics, such as Lebanon’s. For Lebanon, the costs of continuing to respond without adequate data or insight would greatly outweigh the cost and complexities of such a survey. A Lebanese survey would also contribute to a greater regional understanding of the magnitude and dynamics of the Middle East’s epidemics.

In November 2007, with the support of the World Bank, the NAP recruited the American University of Beirut, in collaboration with 6 NGOs, to implement the first Integrated BIO-BSS in Lebanon. The study targets IDUs, FSWs, MSM, and prisoners.

The Integrated Bio-BSS Survey (IBBS) Survey is still ongoing and will end in November 2008. By then, the study team would have hopefully reached the following objectives:

Provide an estimate of HIV prevalence among 4 major vulnerable groups in Lebanon namely MSM, prisoners, commercial sex workers (CSWs), and intravenous drug users (IVDUs).

Provide an estimate in the same vulnerable groups of levels of coinfection with hepatitis B and C among those tested positive for HIV. [Note that the issue of coinfection has been inadequately researched in the international literature, and there are no such studies to our knowledge in the Middle East region. Because HIV and hepatitis B virus have a similar mode of transmission, it would be of value to study hepatitis B infection in these groups, particularly because occult (silent) hepatitis B infection has been reported to be high in individuals with HIV. On the other hand, hepatitis C virus is expected to be high among IVDUs (and perhaps among prisoners). The opportunity is therefore there to study coinfection among these categories].

Provide an estimate of level of infection of hepatitis C virus among the entire IVDU population.

Foster research collaboration for the project between NGOs involved with the vulnerable groups, the NAP, and the American University of Beirut and contribute to building the research capacity of the NGOs involved.

Estimate the population size of the 4 vulnerable groups using the multiplier method.

Use the above HIV prevalence data to better calibrate national HIV estimates in Lebanon.

Enhance our understanding of the geographic, age, gender, and socioeconomic distribution of HIV infection among the 4 vulnerable groups.

Characterize sexual and injecting drug use practices and relevant HIV knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among individuals in the 4 vulnerable groups.

Gain greater insight into major HIV transmission dynamics among the 4 vulnerable groups in Lebanon.

Gain an indication of coverage of existing HIV prevention, testing, and treatment services among the 4 vulnerable groups.

Develop a body of biobehavioral data to inform intervention development, and

Develop an operational manual and training guide for integrated biobehavioral surveillance in Lebanon in English. These materials, if translated into Arabic, could serve as a regional resource for biobehavioral surveillance in the Middle East region.

HIV Epidemic Profile in Lebanon

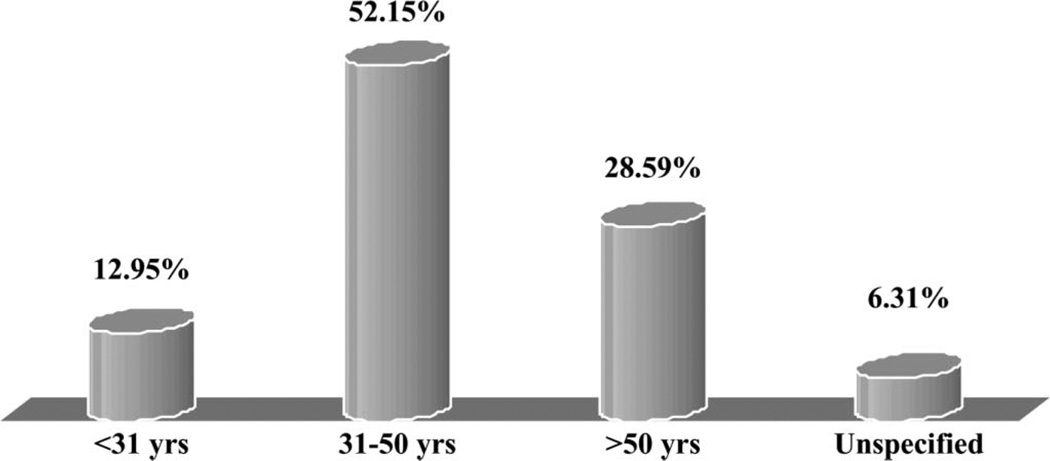

According to the NAP of Lebanon, of the cases reported to date in Lebanon: 38.5% are asymptomatic, 37% living with AIDS, and 17.8% unclassified; 79.5% are male; 79.3% were infected through sex, 6.3% through blood transfusion, 5.5% through injecting drug use, and for 6.2%, the mode of infection is unclassified; 2.7% are below 31 years, 53.2% are between 31–51 years, 31.7% are above 50 years, and for 2.42%, the age is unclassified; and 55.1% had traveled abroad, 42.5% had not, and for 2.4%, this indicator was unclassified.

Again, until today, most of the data on HIV are based on case reporting. In Lebanon, reported cases are at a rise from the year 2006. In 2007, there were a total of 98 new cases, which amounted to 1056 cumulative cases. Furthermore, there are minimal acceptable variations in trends related to gender distribution. Infections among persons with no travel history are also at a rise, hence confirming an increase in local transmission. Infections among the vulnerable groups are at stable rates, and the age distribution is showing more or less younger age groups.

During the year 2005, the NAP has received 95 new reported cases, among them, 81 are males and 14 are females. The total number of reported cases till this date reached 903 cases, of which, 81.7% are males and 17.8% are females. Among those, 392 are HIV positive, 318 AIDS, and 193 unspecified. 52.2% are patients within the age group of 31–50 years of age, compared with 57.7% in 2004, thus demonstrating that the disease is becoming less specific to one age group. Also, 51.4% had no travel history, whereas only 41.4% reported having traveled abroad.

Furthermore, a careful examination of the reported cases reveals that close to 21.0% of them are listed as “not specified,” whether HIV infected or people who have developed AIDS. Statistics indicate that the probable modes of transmission are sexual (76.0%), transfusion (6.0%), IVDU (5.0%), perinatal (2.0%), and the rest of the cases are unspecified. No clear trend in terms of the socioeconomic status of the infected or those living with the disease. Records are not clear on more than 60% of the reported cases. However, among those whom their profession is reported, HIV/AIDS has hit on equal footing highly recognized professions (medical and paramedical, engineering, teachers) and skilled and unskilled laborers. One thing is certain that the epidemic is mostly prevalent among the male population in Lebanon (82%).

The Vulnerable Groups

No one is safe from getting the disease if his/her actions that can lead to HIV infection are not protected. There was an agreement that the major determinant of the epidemic is behavioral, which is mainly characterized by unprotected sexual intercourse and multiple sexual partners. In general, there was a consensus that the most vulnerable group was the youth, mainly those aged between 15 and 24 years. In addition, migrants; including those who travel outside Lebanon and foreigners who come to work in Lebanon; sex workers; drug abusers; MSM, poor and low-income society; married women with infected husbands; victims of gender-based violence, such as rape victims; and people who lack education and awareness of the disease were perceived as groups at high risk of contracting HIV/AIDS.

Other groups were considered to be at vulnerability but not as common as the above. These included subjects who cannot reach means of protection, child laborers, handicapped individuals, tourists, refugees, health workers, truckers, and people with violent behaviors.

The vulnerability of these groups, especially the youth, is predetermined by their careless behaviors, curiosity to experience new things, lack of sexual education in schools, and the stigma behind the disease. The cultural taboo is seen as a driving force behind women living with the disease not reporting it especially if they got it from their husbands. Furthermore, other determinants included the low status of women, illiteracy, stigma, and discrimination. In addition, low socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, migrant labor, and commercial sex workers, have lead to sex work and drug abuse, in addition to sharing needles and having unprotected sex with multiple partners.

Youth

Despite the fact that HIV/AIDS is highly prevalent among the 31- to 50-year-old population, the youth are affected and they are most vulnerable. From the 903 reported cases, 12.95% of people with HIV/AIDS are younger than 31 years (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of HIV cases according to age in Lebanon. Adapted from NAP report, December 2005.

The vulnerability of this group has to be taken seriously as they are often characterized as careless, rebellious, and curious to experience new ways of approaching life.

Studies have shown that there is variability in the level of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among the youth. This variability is due to several factors including their socioeconomic status and whether they are in or out of school. KABP studies have shown that students of the public and semiprivate schools had lower exposure to health information and display less positive attitude toward HIV/AIDS-preventive measures. Furthermore, out-of-school youth are at a higher risk. They tend to engage in unsafe sex; the behavior of which is intended as a means of survival, comfort, and reaction to life stressors.

Migrants

Lebanon has long been associated with migration to and from the country. Political instability and the economic recession have been the triggers over the past century for many adults to emigrate in search for stability and wealth. This has led some individuals to get involved in high-risk behaviors including multiple sexual partners, commercial sex, and increased use of alcohol and drugs. The implications of that are the high risks to disease transmission they tend to impose on their loved ones when they come back home. At the same time, Lebanon is a host to a great number of migrant workers including tourists, business travelers, casual laborers, and sex workers. Their behavior in their own country and the subsequent activity in Lebanon are of concern as they tend to be the double agent in a secret service carrying a double jeopardy to those encountered in Lebanon and those waiting in their homeland.

Prisoners

Not much research has been done about prisoners. From the scanty information available, few cases of HIV/AIDS have been reported over the years. One main issue is the process of testing new inmates upon arrival to the prison facility and their isolation before distribution on the various facilities. There is a concern that due to the bureaucracy in the system, inmates get distributed even before the results of testing are issued. Furthermore, there was a concern regarding their health needs, including physical and psychological. It was recommended that a vocational training unit be established to relieve some of the stress, and some counseling services.

Armed Forces

It has been reported, based on a focus group discussion with 21- to 26-year-old student officers, that the enrollees might have some high-risk behaviors such as having sex with multiple partners coupled with inconsistency in use of condoms and the occasional use of unsterilized skin piercing devices. This is further complicated by the limited access to information about HIV/AIDS and its prevention.

Another source of risk to the armed forces is the occupational hazard among the staff who might come in contact with infected criminals either during detention (judiciary police) or during prison watches and services to prisoners (guards and health workers). Otherwise, the risk of contracting the disease resembles that of the general population, depending on the behavioral characteristics of the individuals.

Nevertheless, the incomplete reporting did not prevent stakeholders from acting. Some strategies were implemented in Lebanon to fight HIV/AIDS development. The National AIDS Control Program (NAP) has worked on increasing the political involvement and on applying programs with NGOs, nationwide. This has been associated with campaigns through the media to educate the public, increase their awareness, and reduce the stigma associated with the disease. The fact remains that the low prevalence is not alarming for the leaders. Given the national priorities, the expansion of the national response to HIV/AIDS is bound to face some major challenges: the lack of competent human resources, the limited access to affordable medications and health care services, and the limited financial resources to support such a response.

Given the elements mentioned earlier and the risks encountered by the vulnerable groups, HIV/AIDS could emerge in a few years as a primary threat in Lebanon, which will affect major sectors including health, social affairs, tourism, and labor. It will be an additional burden on a slowed down economy, increasing costs of health care, and a social structure barely developed after years of civil troubles. The epidemic could rapidly spread among the “occidentalized” youth who are characterized by a rebellious attitude against a too conservative community. The development of the epidemic could also be promoted by the fact that more and more people are living under the poverty threshold and that some sectors of tourism try to become more active by importing FSWs. The trend of previous years shows that the epidemic is not vanishing and that it could strike hard at any moment unless multisectoral intervention programs coordinated at the national level coupled a continuous M&E system are implemented.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Lessons Learned

The MOH are sole responsible for combating the HIV epidemic in the MENA countries. It is true that they are building collaboration with various national and international players, yet the MOH carry the burden of facing the HIV epidemic.

The national HIV efforts in the MENA countries are founded mainly on passive surveillance, and the active surveillance attempts are insufficient. This fact renders the systems incapable of providing the information necessary to understand the magnitude, dynamics, and the speed of spread of infection to promptly respond to the epidemic status in these countries.

The HIV status is not any more a low epidemic in some of the MENA countries. Sudan is already facing a generalized epidemic. Egypt, Libya, and the countries of the Arab Maghreb, and probably others, are stepping toward a concentrated epidemic. The countries in the Gulf area suffer from serious lack of information that hinders efforts to characterize the level of the epidemic.

HIV infection in the MENA countries affects the adults in the prime of their lives who in turn loose their health and productivity thus depriving families, communities, and entire nations of their most productive people. It is expected that there will be an increased demand for treatment and the follow-up of viral load of treated cases. The ART and the follow-up testing are expensive, and the economy in all countries, even the richest, can hardly bear this huge economic burden.

It is possible that the conservative culture in the MENA countries has helped in slowing down the progress of the HIV epidemic, yet these conservative norms do not mean that MENA region is not at risk of the spread of HIV infection as some people living in these countries, whether nationals or foreigners, do engage in risk behaviors. It is true that the high-risk groups represent a minor fraction of the population, but their existence cannot be denied and their links with general population cannot be neglected. Ignoring the presence of the high-risk groups in the region will only serve the spread of HIV unperceived.

HIV transmission in the MENA countries is mainly due to risk behaviors, yet, blood-borne infections and mother-to-child transmissions are evident. Countries where blood-borne diseases as viral hepatitis B and C find route and score high prevalence, are at very high risk of HIV spread since they share the same made of transmission. The experience in Egypt, nationally reported data, and Sudan, estimated by UNAIDS, prove that mother-to-child transmission is active with the risk of more infected newborns. Thus there is an emerging need to secure the rights of these children to access education, health care, and be accepted in the society.

The myth that high-risk groups, as FSWs, IDUs, and the MSM, are unreachable and collecting data on risk behaviors is undoable in the MENA culture proved to be erroneous. The first round BIO-BSS in Egypt and Lebanon has proved that well-planned and strictly supervised ethical surveys are able to reach hidden populations and provide invaluable information on risk practices. The high-risk groups are in need of tailored preventive programs to reduce risk behaviors in addition to health care and social support. High-risk groups can be reached through their networks and are open to provide information on risk practices.

In addition to the high-risk groups, multiple vulnerable groups exist in the MENA countries. Egypt has identified street children, and Lebanon has identified the youth, the migrants, the prisoners, and the armed forces. These groups are in need of social and health interventions. Street children in Egypt, boys and girls, do not enjoy access to educational opportunities and exposure to HIV prevention messages; they lack economic security and protection under law; and in addition, they are liable to sexual violence from same or opposite sex and have little chance to negotiate safe sex which contributes to their vulnerability to HIV infection. The youth are always curious to experience risk behaviors; their limited experiences in life, especially in the absence of HIV educational interventions in most countries, place them on the rocks of HIV infection. Migrants, prisoners, and armed forces live hard life; they are most of the time away from their families and have little opportunity to live a normal sexual life which force them to risk practices and MSM activity increasing their vulnerability to HIV infection.

In the MENA region, both men and women are victims of HIV infection. Risk behaviors are at the core of HIV transmission and such behaviors are socially determined. On one hand, males are the breadwinners, freely mobile, have lots of social networks, and the society may accept that they have multiple sexual partners. Furthermore, in case of limited resources, men are pushed on the street looking for income-generating activities. These factors may expose men to experience risk behaviors as injecting drugs or practicing unsafe sex. On the other hand, although females are biologically more susceptible to HIV infection than males, yet they still suffer from gender norms that make them less exposed to sexual knowledge, less able to negotiate safe sex, and more vulnerable to sexual assaults; in addition, the limited family resources may still push some females to practice risk behaviors. This emerges the need for programs tailored to the specific circumstances in which men and women live and the way they are raised.

Barriers to Policies and Surveillance Efforts

Any attempt to set HIV-specific policies in the MENA countries will be faced by 1 or more of the following challenges: stigma, gender model, biomedical health care model, and limited resources.

Although the cultural norms in MENA countries are strong protective means, such norms often contribute to strong stigmatization and social exclusion of people practicing risk behaviors and those living with HIV/AIDS. The stigma and discrimination act on 3 levels. First, the perceived shame and disgrace that people practicing risk behavior or living with HIV infection put on their families force them to conceal their lifestyles and avoid seeking counseling, HIV testing, social support, or health care. These people become detached from the society that rebels their presence. Second, health care providers rarely admit that risk behaviors and HIV infection are issues that need special health care and social support. Given the HIV phobia, several health care providers may refuse to care for PLHA as they fear catching the infection. Furthermore, PLHA are not welcomed in many health care facilities that risk losing clients. Third, there is a widespread national denial of the existence of risk behaviors and HIV infections in several MENA countries, and thus excluding them from surveillance systems. In many countries in the region, there is general delusion that issuing policies for combating HIV is perceived as if the national authorities are in opposition to the cultural norms and religious beliefs in the country and is approving the legitimacy of risk practices. There is a serious misconception between the rights of the high-risk groups to benefit from HIV prevention and care programs and the rights of the society to refuse the risk practices.

The gender model applied in most MENA countries is skewed in favor of females. Most gender efforts focus on women, and the true gender approach is not sufficiently applied. The issue of women vulnerability to HIV has been the focus of most HIV programs for more than a decade. There are currently enormous national efforts to empower women and improve their position in the MENA region. Males receive less attention, and there are hardly programs that seek to empower men and reduce their family burden.

The national health policies in the MENA countries apply a biomedical model with the MOH as the sole responsible. It is true that multiple other national sectors help to provide HIV interventions, yet their roles and responsibilities are ill defined. The national health policies lack the intersectoral vision in facing health issues. This explains the limited attention to the importance of potent surveillance systems that are the only producers of reliable evidence necessary for policy decision making. In addition, the lack of the intersectoral approach is responsible for the limited HIV prevention programs and social interventions as compared with the concentrated treatment-oriented actions. The biomedical model is not suitable to face the HIV epidemic, given the nature of infection that is incurable till present and has serious prognosis. The treatment focus leads to great loss in terms of productive population and financial resources.

Several MENA countries suffer from limited resources that are reflected on the income of people, the quality and quantity of health care, and the limited government resources. In the absence of health insurance schemes in several MENA countries, people are unable to pay for HIV testing, health care, and monitoring of disease progression, if HIV infected. The MOH in all countries carries the burden of providing free HIV testing and health care, however, given the expected increase in the number of people seeking HIV care, the MOH face difficulties to sustain its financial contributions in the coming years. The national governments face plenty of health and nonhealth priorities, thus, they are expected to suffer from much economic burden that may menace the development efforts.

The Way Forward

It is time that the MENA countries look ahead to the HIV/AIDS epidemic as a national threat even if right now countries face low epidemic scenarios. Decision makers should push the HIV epidemic on the national health agenda. There is evidence that the epidemic is growing, and there is no reason for lack of recognition or widespread denial. There is also evidence of emerging needs for the various population categories, even the children, which need to be promptly addressed and resolved.

Countries are requested to spend time and effort to allocate national and international resources for HIV control programs. Countries can go further and push for mainstreaming HIV/AIDS as a priority in the poverty reduction strategy, thus, they can ensure that adequate resources are allocated to national programs aiming to abort the epidemic and monitor its progress. In this case, HIV/AIDS will be a priority on the development agenda and a prerequisite for full government mobilization against HIV/AIDS and its possible social and economic impact in region.

Strategies and policies targeting HIV/AIDS in the region should go beyond the narrow health sector focus and view the HIV epidemic as a multisector responsibility. The MOH in each country is encouraged to build and strengthen partnership with other ministries, civil society, and NGOs. Well-defined roles and responsibilities should be shared between the various national sectors. The national programs proved to be most effective when a combination of multisector interventions are tailored to the specific risk factors and the epidemic status of the country.

HIV is a pandemic touching the globe and threatening people everywhere. The fight against HIV should be shared by all countries. The national authorities are invited to strengthen their networks with other countries worldwide and learn from the HIV experience elsewhere.

The urgency for the need of valid and reliable evidence on the HIV epidemic status should be acknowledged. Countries should be urged to report regularly HIV data on national and international levels. Periodic reporting with standardized forms on the necessary information should be published regularly. Consensus should be made to ensure that all countries report regular and timely complete reliable HIV data.

The development of potent second-generation surveillance systems must be the mainstay to provide the evidence necessary for decision making. The national efforts should continue to build and strengthen the national HIV surveillance systems and build the staff capacities in the context of the 3 ones. It is wise that countries work on identifying the high-risk and vulnerable groups within their territories and the best means to reach them not only for surveillance purposes but also for service provision. Countries should, also, work on finding out the best surveillance strategies that allows merging and collecting biological and risk data.

MENA countries should put more efforts in developing a national strategic plan encompassing a gender approach. The role of men and women in HIV/AIDS prevention and care should be emphasized, and both of them should be engaged as actors in the fight against HIV/AIDS rather than just looked at as helpless victims of societal norms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization. AIDS Epidemic Update 2007. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kandela P. Arab nations: attitudes to AIDS. Lancet. 1993;341:884–885. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93079-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obermeyer CM. HIV in the Middle East. BMJ. 2006;333:851–854. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38994.400370.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley L, Eberstadt N. Behind the Veil of a Public Health Crisis: HIV/AIDS in the Muslim World. NBR Special Report. Seattle, WA: National Bureau of Asian Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Mazrou Y. HIV/AIDS epidemic features and trends in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:100–104. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2005.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kallajieh W. Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Lebanon from 1984 through 1998. Int J Infect Dis. 2000;4:209–213. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(00)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elmir E, Nadia S, Ouafae B, et al. HIV epidemiology in Morocco: a nine-year survey (1991–1999) Int Jf STD AIDS. 2002;13:839–842. doi: 10.1258/095646202321020125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins C, Robalino DA. HIV/AIDS in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), 1987 revision of CDC/WHO case definition for AIDS. Weekly epidemiological record. 1988;63:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNAIDS/WHO working group on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance. Summary of AIDS case definitions in use world-wide, 1997. [Accessed January 2008]; Available at: http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub01/JC240-SexTransmInfSurv_en.pdf.

- 11.WHO Regional Office for Eastern the Eastern Mediterranean. EMRO AIDSnews. [Accessed February 2008];1999 Jun;Vol. 3(No. 2) Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/aidsnews/june1999/BriefNews.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNAIDS. Sudan Epidemiologic fact sheet. [Accessed February 2008]; Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/CountryResponses/Countries/sudan.asp.

- 13.El-Sayed N, Volle J, El Taher Z, et al. National HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance Plan. Cairo, Egypt: MOHP, FHI/IMPACT, USAID; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Sayed N, Soliman C, Abd el Sattar A, et al. Evaluation of Selected Reproductive Health Infections in Various Egyptian Population Groups in Greater Cairo. Cairo, Egypt: MOHP, FHI/IMPACT, USAID; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.FHI. Egypt brochure. [Accessed March 2008]; Available at: http://www.fhi.org/en/CountryProfiles/Egypt/index.htm.

- 16.FHI Egypt. Egypt Final Report (April 1999 – September 2007). USAID’s Implementing AIDS Prevention and Care (IMPACT) Project. Arlington, USA, VA: FHI; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.FHI Egypt. Middle East and North Africa Region Final Report (March 2005 – June 2007). USAID’s Implementing AIDS Prevention and Care (IMPACT) Project. Arlington, USA, VA: FHI; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amon J, Brown T, Hogle J, et al. Behavioral Surveillance Surveys: Guidelines for Repeated Behavioral Surveys in Populations at Risk of HIV. Arlington, Virginia, VA: Family Health International (FHI) HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Department; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.MOHP/FHI Egypt. HIV/AIDS Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey: Summary Report. MOHP, FHI/IMPACT; USAID Cairo, Egypt: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National AIDS Control Programme in Lebanon. Knowledge, Attitude, Beliefs and Practices of the Lebanese Population Concerning HIV/AIDS. Beirut, Lebanon: Ministry of Public Health and WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS and World Bank. National AIDS Councils: Monitoring and Evaluations Operations Manual. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; Washington, D.C.: The World Bank; 2002. and 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2006. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS: 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. [Google Scholar]