Abstract

BACKGROUND

When compared to ultrasound, computed tomography scans (CT) are more expensive, have significant radiation exposure, and have lower sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values for patients with gallstone disease.

METHODS

We reviewed data on patients emergently admitted with complicated gallstone disease between 1/2005 and 5/2010. The use of CT and ultrasound imaging on admission was described. Multivariate logistic regression was used to evaluate factors predicting receipt of CT.

RESULTS

562 consecutive patients presented emergently with complicated gallstone disease. The mean age was 45 years. 72% of patients were female, 46% were white, and 41% were Hispanic. 72% of patients had an ultrasound during the initial evaluation and 41% had a CT. Both studies were performed in 25% of patients (n=141), while 16% (n=93) had CT only and 47% (n=259) had ultrasound only. CT was performed first in 67% of those who underwent both studies. Evening imaging (7pm–7am; OR=4.44, 95% CI 2.88–6.85), increased age (OR=1.14 per 5-year increase, 95% CI 1.07–1.21), leukocytosis (OR=1.67, 95% CI 1.10–2.53), and hyperamylasemia (OR=2.02, 95% CI 1.16–3.51) predicted receipt of CT.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates the overuse of CT in the evaluation of complicated gallstone disease. Evening imaging was the biggest predictor of CT use, suggesting that CT is performed not to clarify the diagnosis, but rather a surrogate for the indicated study. Surgeons and emergency physicians should be trained to perform right upper quadrant ultrasounds to avoid receipt of unnecessary studies in the appropriate clinical setting.

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that over 20 million Americans have gallstones. Annually, this leads to over one million hospitalizations, 750,000 cholecystectomies, and over $6 billion in costs.1–4 The evaluation of patients who present with right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain includes history, physical examination, laboratory studies and imaging. No single physical finding or laboratory test is sufficient to definitively diagnose or exclude gallbladder disease as the cause of symptoms without the need to perform imaging studies.5

The American College of Radiology recommends abdominal ultrasound as the initial diagnostic imaging in the evaluation of patients with right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans are indicated after a negative or equivocal ultrasound, particularly for identification of other abdominal disorders or when complications from acute gallbladder disease are suspected.6 Compared to CT, ultrasound is readily available and easy to perform, less expensive, and does not involve any radiation exposure. Ultrasound has a sensitivity and specificity above 95% in the identification of gallstones.7–9 The presence of gallstones and ultrasound findings of pericholecystic fluid, a sonographic Murphy’s sign, and gallbladder wall thickening in the setting of RUQ pain is between 83–97% sensitive and 64–95% specific in diagnosing acute cholecystitis.10–12 In addition, ultrasound has a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 97% for detection of common bile duct dilatation.13 Many gallstones are not radio-opaque. As a result, CT has much lower sensitivity (39–75%) for detecting gallstones when compared to ultrasound.8, 10, 14

A recent study reported doubling in the use CT scans in the evaluation of patients presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) with abdominal pain between 2001 and 2005.15 Given this trend and the patterns we anecdotally observed in our ED, we hypothesized that CT was overutilized in patients presenting to the ED with acute gallbladder disease, despite CT not being the imaging modality of choice. The goal of this retrospective cohort study was to determine current patterns in the use of ultrasound and CT in the evaluation of patients with acute gallbladder disease at a single institution, and to determine patient and hospital characteristics that predict inappropriate use.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

We performed a retrospective review of a combined prospectively and retrospectively collected database of 562 patients admitted to our institution through the ED between January 2005 and May 2010 with acute gallbladder disease. Between September 2008 and February 2009 the hospital was closed after been severely damaged by hurricane Ike. When it reopened, a cholecystectomy critical pathway was implemented with the aim to improve cholecystectomy rates in order to comply with national guidelines regarding treatment for acute gallbladder disease.16 After pathway implementation, cholecystectomy rates increased from 48% to 78% during initial admission. In case of acute cholecystitis, cholecystectomy was indicated within 48hrs of admission while for patients with pancreatitis or choledocolithiasis, it was indicated within 48hrs of resolution of symptoms. The pathway only affected the surgical management of patients with acute biliary disease and did not affect the initial evaluation of these patients in the ED and did not involve the decision making process of the ED physician staff.

Data source and patient information

Data were collected prospectively on patients admitted emergently to the hospital with acute gallbladder disease including acute cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis and choledocholithiasis after January of 2009 when the pathway was implemented. Data before 2009 had been collected retrospectively and analyzed before pathway implementation. Data were obtained from prospective/retrospective chart reviews of paper (from January 2005 and November 2007) and electronic medical records (December 2007 to present). Data collected for analysis included patient age, race and ethnicity, primary diagnosis, comorbidities, and health behaviors. Hospital variables included the time and day of the week the patient was evaluated in the ED, previous ED visits for gallstone disease, and admitting service. Detailed data on radiologic studies including performance of each study and the findings were recorded. Studies included right upper quadrant ultrasound, abdominal CT, hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Laboratory data for each patient were collected on admission and included white blood cell count, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, amylase, and lipase. Outcome variables were the receipt of a right upper quadrant ultrasound and/or an abdominal CT during the evaluation of suspected acute gallbladder disease in the ED.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis were done using SAS software (Version 9.2 – Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics on the overall cohort were expressed as percentages for categorical variables and mean with standard deviations or medians/ranges depending on the variable distribution. Time of day was defined as evening imaging if it was done between 7:00 pm and 7:00 am of the following day. Imaging was considered weekday imaging if it occurred Monday through Friday and weekend imaging if it occurred Saturday or Sunday. Laboratory values were classified as abnormal if the white blood cell count above 12,000/mm3, total bilirubin over 2 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase above 122 Units/L, amylase over 110 Units/L and lipase over 220 Units/L, based on upper limits of normal in our laboratory.

A Cochrane-Armitage test for trend was used to evaluate the trend in the use of CT in patient with gallbladder disease during the study period. Statistical significance was considered to be P<0.05.

Bivariate analysis was performed comparing patients who did and did not receive an abdominal CT during their evaluation for suspected acute gallbladder disease, using chi-square for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Statistical significance was considered to be P<0.05.

Using a multivariate logistic regression model, we identified factors that independently predicted receipt of CT scan during initial evaluation of suspected gallbladder disease. Odds ratios were referenced to a single group specified for each variable. The initial model included patient demographics, comorbidities and health behaviors, hospital factors and laboratory values. Stepwise backwards methods were used to generate a parsimonious model using the likelihood ratio test and Akiake Information Criteria (AIC). Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported.

RESULTS

Cohort characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were 562 patients in the overall cohort. Mean age was 45.0 ± 20.0 years old. (Median = 43 years, range 6 – 97). The majority of patients were female, white or Hispanic, and admitted to a surgical service. Sixty-five percent (65.3%) had an admission diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, 11.0% had common bile duct stones, and 23.7% had gallstone pancreatitis. Cholecystectomy was performed during the initial hospitalization in 53.7% of patients.

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics.

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 45.0 +/− 20.0 | ~ |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 168 | 29.9% |

| Female | 394 | 70.1% |

| Race | ||

| White | 256 | 45.6% |

| Black | 65 | 11.6% |

| Hispanic | 228 | 40.6% |

| Other | 13 | 2.3% |

| Discharge diagnosis | ||

| Acute cholecystitis | 367 | 65.3% |

| Common bile duct stones | 62 | 11.0% |

| Gallstone pancreatitis | 133 | 23.7% |

| Admitting service | ||

| Surgical | 412 | 73.3% |

| Non-surgical | 150 | 26.7% |

| Weekend (S/S) admission | 143 | 25.4% |

| Comorbidities* | ||

| CAD | 51/559 | 9.1% |

| MI | 16/554 | 2.9% |

| Diabetes | 79/554 | 14.3% |

| Hypertension | 186/555 | 33.5% |

| COPD | 14/554 | 2.5% |

| Malnutrition | 3/554 | 0.5% |

| Smoker | 111/553 | 20.1% |

| EtOH | 39/554 | 7.0% |

CAD: Coronary Artery Disease, MI: Myocardial infarction, COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, EtOH: Alcohol dependence

Percentage calculated from patients with available data.

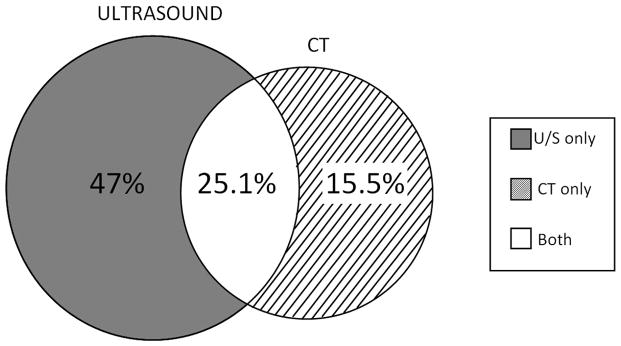

Seventy-two percent (72.1%) of patients had an ultrasound during the initial evaluation and 40.6% had a CT. No CT or ultrasound imaging was performed in 12.3% of the patients, 47.0% had an ultrasound only, 15.5 % had a CT only, and 25.1% had both a CT and ultrasound (Figure 1). In the subgroup of patients that received a CT scan, only 10.6% were ordered by a member of the surgical team, with the remainder being ordered by the ED or Medicine providers. More than half (52.1%) of the patients receiving a CT were evaluated between 7 pm and 7 am. Only 31.2% of patients receiving an ultrasound were evaluated between 7 pm and 7 am. In those who underwent both imaging procedures, CT was performed prior to ultrasound in 67% of patients. Of the 95 patients who had a CT first, 20% required further ultrasound evaluation due to inconclusive results from the CT scan and, in all cases, the ultrasound identified gallstones and/or signs of acute cholecystitis. Also, in more than 50% of patients with signs of acute pancreatitis or dilated common bile duct, gallstones were not evident during initial CT scan, requiring an additional ultrasound that identified gallstones in 87% of these patients. In 15% of patients, we did not find a reason to obtain an additional ultrasound examination, as the CT provided the diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Right upper quadrant ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) distribution among cohort.

No time trend in the use of CT was evident during the study period with 40% to 45% of the patients receiving a CT for the evaluation of acute gallbladder disease in each year from 2005 to 2009, with a decrease to 31.2% in 2010 (P-value = 0.19).

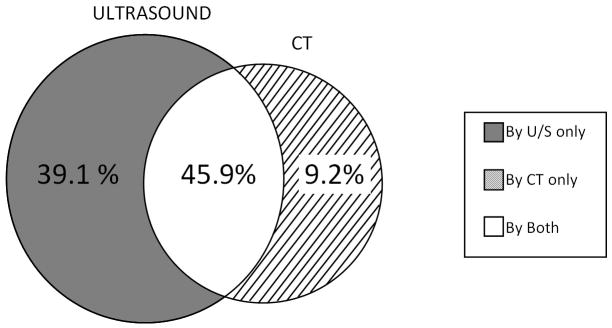

Of the 141 patients who underwent both CT and ultrasound, both studies demonstrated gallstones in 45.9% of patients (n=64, Figure 2). In 39.1% of patients (n=55) CT failed to demonstrate stones seen on ultrasound, while in 9.2% of patients (n=13) CT demonstrated stones not seen on ultrasound. In 6.4% of patients (n=9), neither study demonstrated stones, but ultrasound identified sludge in the gallbladder.

Figure 2.

Gallstone identification by right upper quadrant ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan.

Additional imaging procedures included MRCP in 20.3% of patients, ERCP in 22.5% of patients, and HIDA scan in 4.9%. Studies were not mutually exclusive and many patients received more than one.

The bivariate analysis of variables associated with receipt of CT is summarized in Table 2. Patients who received a CT on admission were more likely to be older, male, admitted to a non-surgical service, and to have undergone imaging during the evening hours. Patients with previous ED visits for gallstone disease were less likely to receive a CT scan on admission. Patients undergoing CT were more likely to have an elevated WBC but all AST, ALT, total bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase were similar between the two groups. Mean amylase and lipase were not calculated as any value over 6000 is reported as >6000 and not with an accurate value. Race, percentage admitted on weekend days, and the diagnosis did not differ between the two groups.

Table 2.

Factors Predicting CT: Univariate Analysis

| CT on admission* (N=234) | No CT on admission (N=328) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 51.5 +/− 19.4 yrs | 40.4 +/− 19.1 yrs | <0.0001 |

| Gender | 0.02 | ||

| Male | 35.9% | 25.6% | |

| Female | 64.1% | 74.4% | |

| Race | 0.06 | ||

| White | 50.9% | 41.8% | |

| Black | 12.8% | 10.7% | |

| Hispanic | 34.2% | 45.1% | |

| Other | 2.1% | 2.4% | |

| Admitting service | 0.005 | ||

| Surgical | 67.1% | 77.7% | |

| Non-surgical | 32.9% | 22.3% | |

| Previous ED visit | 0.0006 | ||

| Yes | 16.1% | 28.8% | |

| No | 83.8% | 71.2% | |

| Evening imaging (7pm–7am) | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 57.3% | 28.4% | |

| No | 33.7% | 71.6% | |

| Weekend imaging (sat/sun) | 0.38 | ||

| Yes | 27.3% | 24.1% | |

| No | 72.7% | 75.9% | |

| Diagnosis | 0.55 | ||

| Acute cholecystitis | 65.8% | 64.9% | |

| Gallstone pancreatitis | 24.8% | 22.9% | |

| CBD stones | 9.4% | 12.2% | |

| Laboratory values | |||

| WBC | 13.3±12.7 | 10.8±4.8 | <0.0001 |

| Total bilirubin | 1.7±2.7 | 1.6±2.1 | 0.53 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 152±118 | 168±137 | 0.17 |

| Elevated amylase | 50.0% | 40.1% | 0.08 |

ED: Emergency department, CBD: Common bile duct, WBC: White Blood Cells.

CT performed on or 48hrs within admission

Table 3 presents the results of a multivariate logistic regression analysis evaluating factors independently associated with receipt of CT. Evening imaging was the single largest predictor of CT use. Patients imaged between 7 pm and 7 am were greater than four times more likely to get a CT (OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.88 – 6.85). With each 5-year increase in age, patients were 14% more likely to get a CT (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.07–1.21). Likewise, an elevated WBC (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.10 – 2.53) and elevated amylase (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.16 – 3.51) were associated with an increase in CT use. Patients with hypertension were more likely to get a CT (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.20 – 3.37), while other comorbidities were not independent predictors. Weekend admission, gender, race, previous ER visits, diagnosis (acute cholecystitis vs. gallstone pancreatitis vs. common bile duct stones), and other laboratory values did not predict use of CT scanning.

Table 3.

Factors Predicting CT: Multivariate regression model.

| OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Evening imaging | ||

| 7am – 7pm | 1.00 | REF |

| 7pm – 7am | 4.44 | 2.87 – 6.85 |

| Age (5 year increments) | 1.14 | 1.07 – 1.21 |

| White blood cells count | ||

| Normal | 1.00 | REF |

| Abnormal | 1.67 | 1.10 – 2.53 |

| Amylase | ||

| Normal | 1.00 | REF |

| Abnormal | 2.02 | 1.16 – 3.51 |

| Hypertension | ||

| No | 1.00 | REF |

| Yes | 2.01 | 1.204 – 3.368 |

Weekend admission, gender, race, previous ED visits, diagnosis, other comorbidities, and other laboratory values did not predict use of CT scanning.

In 224 patients out of the 234 that received a CT during admission, data was available for extensive chart review. In seventy-nine patients (34.3%) CT was not indicated as patients presented with a clear clinical picture of acute gallbladder disease without signs of complications and ultrasound was indicated as the initial and only test in that clinical setting. Based on the 2011 Medicare reimbursement rate for CT with and without contrast, unnecessary imaging in the management of these patients during the study period represents an additional cost of $64,000 for our institution.

Patients who didn’t undergo cholecystectomy on initial admission were more likely to receive duplicate and unnecessary tests in subsequent hospital visits. After the initial admission, 15.8% of patients in this group underwent one additional ultrasound, 3.5% had two, and 1.9% had three on future ER visits or hospital admissions. Likewise, 6.5% had an additional CT and 1.5% had two additional CTs during subsequent visits for abdominal pain.

DISCUSSION

Although ultrasound is the diagnostic imaging test of choice during the acute presentation of suspected gallstone disease, at our tertiary referral center only 72% underwent RUQ ultrasound and 41% underwent CT imaging. 25% of patients who underwent a CT also had an ultrasound and in two thirds of cases, an ultrasound was necessary and performed after the CT scan. This finding is consistent with recently described trends in imaging use. Pines et al. recently studied current trends in the use of diagnostic image modalities in patients presenting to the ED with abdominal pain. Between 2001 and 2005, CT use more than doubled, from 10.1% to 22.5%. While ultrasound use increased as well, this increase was more modest, from 11.1% to 13.6%.15 Likewise, a 2010 study by Dinan et al. demonstrated that imaging costs among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer increased from 1999 through 2006, outpacing the rate of increase in total costs among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. The use of CT scanning after cancer treatment had an annual increase of 4–8% for depending on the cancer type.17

This observational study raises concern for indiscriminate use of CT scanning. The magnitude of our results implies significant overuse of CT scanning in this population. In addition, these results are concerning as the rates are nearly double the rates observed in the study by Pines et al.15 that evaluated all patients with abdominal pain, in many of whom CT scans may have been indicated. These additional and unnecessary diagnostic tests will add to the current economic burden of gallstone disease.

We did not formally evaluate the timing of surgical consultation in these patients. However, in our experience, the majority of patients have laboratory and/or radiological tests before the surgical team is involved, in an attempt to establish possible diagnoses that required surgical interventions. In fact, the vast majority of CT scans were not ordered by the surgical team. We continue to encourage early surgical consultation for any patient with abdominal pain and are working to incorporate this into our pathway. However, imaging during evening hours was the strongest predictor of receipt of inappropriate imaging via CT, demonstrating a system problem. In 34.3% of patients the history was consistent with gallstone disease and there was no clear indication for CT scanning. When further examined, we confirmed that this was because the ultrasound technicians are not available in the evenings leading to ordering of CT scans, even when this was not the diagnostic modality of choice. CT scans were performed not to clarify the diagnosis, but rather as a surrogate for the ideal study. This resulted in duplicate studies, with ultrasounds being done in almost two thirds of patients who initially underwent CT. Our results are similar to those published by Kalimi et al.18 who found that ultrasound was used less frequently as the first diagnostic test in patients admitted overnight with acute cholecystitis versus those admitted during the day (43% versus 56% respectively).

We thought that obesity was a possible predictor of CT use. When evaluating our data we found significant differences in the percentage of obese patients before (9.2%) and after (36.1%) pathway implementation. After pathway implementation, height and weight were prospectively collected and BMI calculated in an accurate manner where as this information was not always available and accurately collected in the retrospective review, especially before implementation of the electronic medical record. We assume the obesity rate of the overall cohort is in the range of 36% as would be more typical. Because of this inaccuracy we did not include obesity in our models. However, when obese and normal weight patients admitted post-pathway implementation were compared, there was no statistical difference in the receipt of CT scans between groups and it actually trended toward non-obese patients being more likely to undergo CT scans (43% vs. 26%, P=0.08). Other comorbidities were accurately recorded and did not differ between the groups before and after pathway implementation.16

In patients with a strong clinical suspicion of complicated gallstone disease, ultrasound should be encouraged as the initial and only test for evaluation if no other complications are suspected. Given the increasing availability of bedside ultrasound in the ED, a growing proportion of emergency physicians are now performing their own ultrasound examinations in patients with RUQ abdominal pain to improve patient care and circumvent the type of diagnostic delays seen in our study. Recent studies have shown that surgeons and emergency physicians can be trained to identify cholelithiasis with a sensitivity of 92–96% using bedside right upper quadrant ultrasounds.19–21 Summers et al.21 demonstrated similar results for ultrasound exams performed by trained emergency medicine physicians and radiologists. He also found equivalent results between trained junior residents and senior residents or attending. Young et al.22 calculated that we could save between $48 and $78 million dollars annually if a positive RUQ ultrasound performed by an emergency physician is not followed by additional testing. The use of non-radiologist performed ED ultrasounds (either performed by emergency room physicians or surgeons) will require physician training in emergency ultrasonography23 but has the potential to have a beneficial impact in patient care and contribute to decrease costs.

Besides cost, there has been recent concern about increased radiation exposure due to indiscriminate use of diagnostic imaging.24–26 Radiation exposure as a result of diagnostic medical imaging has increased from 10% in 1980 to 50% in 2006, with CT of the abdomen representing 18.3% of the total exposure dose related to image testing.24, 27 While ultrasound may not be the study of choice for some intraabdominal disease processes, this is not the case for gallstone disease where ultrasound is more sensitive and specific, less expensive, and safer than CT scanning. If similar trends are found at the population or single-institution level it should prompt evaluation of the barriers to obtaining the appropriate study and lead to implementation of system changes that maximize use of ultrasound and minimize unnecessary or inappropriate studies in patients with suspected acute gallstone disease.

Our study has several limitations. It is a single-institution study and our results may not be representative of the national population but may represent a local problem. However, the consistency with trends in imaging seen in other studies is concerning for a more widespread problem. Additional studies at a national level will help to compare trends between different hospitals and regions. In addition, we did not identify the characteristics of the ordering physician and establish its impact in the selected diagnostic test.

In summary, our study demonstrates the overuse of CT in the evaluation of patients with acute gallbladder disease despite being of little additional benefit when compared to right upper quadrant ultrasound. CT was frequently obtained overnight when ultrasound availability was limited, hence, efforts should be aimed to increase accessibility to good quality ultrasounds in order to avoid receipt of unnecessary additional studies, decrease costs and radiation exposure in patients.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CI

Confidence intervals

- CT

Computed tomography

- ED

Emergency department

- ERCP

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatograpy

- HIDA

Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan

- MRCP

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- OR

Odd Ratios

- RUQ

Right upper quadrant

Footnotes

Disclosure information: nothing to disclose

References

- 1.Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999 Sep;117(3):632–639. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim WR, Brown RS, Jr, Terrault NA, El-Serag H. Burden of liver disease in the United States: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2002 Jul;36(1):227–242. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner CA, Bass EB, Talamini MA, et al. Surgical rates and operative mortality for open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Maryland. N Engl J Med. 1994 Feb 10;330(6):403–408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402103300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vollmer CM, Jr, Callery MP. Biliary injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: why still a problem? Gastroenterology. 2007 Sep;133(3):1039–1041. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski NK, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA. 2003 Jan 1;289(1):80–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. [Accessed 03/14/2011];American College of Radiology appropriateness criteria: Right Upper Quadrant Pain. 2010 http://www.acr.org.

- 7.Bennett GL, Balthazar EJ. Ultrasound and CT evaluation of emergent gallbladder pathology. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003 Nov;41(6):1203–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(03)00097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Memel D, Balfe D, Semelka R. The biliary tract. In: Lee J, Sagel S, Stanley R, et al., editors. Computed Body tomography with MRI correlation. 3. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1998. pp. 779–803. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, et al. Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease. Arch Intern Med. 1994 Nov 28;154(22):2573–2581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey RT, Miller WT., Jr Acute biliary disease: initial CT and follow-up US versus initial US and follow-up CT. Radiology. 1999 Dec;213(3):831–836. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.3.r99dc17831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ralls PW, Colletti PM, Halls JM, Siemsen JK. Prospective evaluation of 99mTc-IDA cholescintigraphy and gray-scale ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. Radiology. 1982 Jul;144(2):369–371. doi: 10.1148/radiology.144.2.7089292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuels BI, Freitas JE, Bree RL, et al. A comparison of radionuclide hepatobiliary imaging and real-time ultrasound for the detection of acute cholecystitis. Radiology. 1983 Apr;147(1):207–210. doi: 10.1148/radiology.147.1.6828731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stott MA, Farrands PA, Guyer PB, et al. Ultrasound of the common bile duct in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. J Clin Ultrasound. 1991 Feb;19(2):73–76. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870190203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skucas J. Advanced imaging of the abdomen. 1. Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pines JM. Trends in the rates of radiography use and important diagnoses in emergency department patients with abdominal pain. Med Care. 2009 Jul;47(7):782–786. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819748e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheffield KM, Ramos KE, Djukom CD, et al. Implementation of a critical pathway for complicated gallstone disease: translation of population-based data into clinical practice. J Am Coll Surg. 2011 May;212(5):835–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinan MA, Curtis LH, Hammill BG, et al. Changes in the use and costs of diagnostic imaging among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer, 1999–2006. JAMA. 2010 Apr 28;303(16):1625–1631. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalimi R, Gecelter GR, Caplin D, et al. Diagnosis of acute cholecystitis: sensitivity of sonography, cholescintigraphy, and combined sonography-cholescintigraphy. J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Dec;193(6):609–613. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowland JL, Kuhn M, Bonnin RL, et al. Accuracy of emergency department bedside ultrasonography. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2001 Sep;13(3):305–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1035-6851.2001.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scruggs W, Fox JC, Potts B, et al. Accuracy of ED Bedside Ultrasound for Identification of gallstones: retrospective analysis of 575 studies. West J Emerg Med. 2008 Jan;9(1):1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Summers SM, Scruggs W, Menchine MD, et al. A prospective evaluation of emergency department bedside ultrasonography for the detection of acute cholecystitis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Aug;56(2):114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young N, Kinsella S, Raio CC, et al. Economic impact of additional radiographic studies after registered diagnostic medical sonographer (RDMS)-certified emergency physician-performed identification of cholecystitis by ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2010 Jun;38(5):645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mateer J, Plummer D, Heller M, et al. Model curriculum for physician training in emergency ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med. 1994 Jan;23(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 27;361(9):849–857. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillman BJ, Goldsmith JC. The uncritical use of high-tech medical imaging. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):4–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1003173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith-Bindman R. Is computed tomography safe? N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1002530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mettler FA, Jr, Thomadsen BR, Bhargavan M, et al. Medical radiation exposure in the U.S. in 2006: preliminary results. Health Phys. 2008 Nov;95(5):502–507. doi: 10.1097/01.HP.0000326333.42287.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]