Abstract

The high recurrence rate of secondary cataract (SC) is caused by the intrinsic differentiation activity of residual lens epithelial cells after extra-capsular lens removal. The objective of this study was to identify changes in the microRNA (miRNA) expression profile during mouse SC formation and to selectively manipulate miRNA expression for potential therapeutic intervention. To model SC, mouse cataract surgery was performed and temporal changes in the miRNA expression pattern were determined by microarray analysis. To study the potential SC counterregulative effect of miRNAs, a lens capsular bag in vitro model was used. Within the first 3 wks after cataract surgery, microarray analysis demonstrated SC-associated expression pattern changes of 55 miRNAs. Of the identified miRNAs, miR-184 and miR-204 were chosen for further investigations. Manipulation of miRNA expression by the miR-184 inhibitor (anti-miR-184) and the precursor miRNA for miR-204 (pre-miR-204) attenuated SC-associated expansion and migration of lens epithelial cells and signs of epithelial to mesenchymal transition such as α-smooth muscle actin expression. In addition, pre-miR-204 attenuated SC-associated expression of the transcription factor Meis homeobox 2 (MEIS2). Examination of miRNA target binding sites for miR-184 and miR-204 revealed an extensive range of predicted target mRNA sequences that were also a target to a complex network of other SC-associated miRNAs with possible opposing functions. The identification of the SC-specific miRNA expression pattern together with the observed in vitro attenuation of SC by anti-miR-184 and pre-miR-204 suggest that miR-184 and miR-204 play a significant role in the control of SC formation in mice that is most likely regulated by a complex competitive RNA network.

INTRODUCTION

Cataracts are a major ophthalmologic concern, with an incidence throughout the population (1,2). Cataracts can result from eye injury through trauma, exposure to sunlight and a variety of age-related physiological manifestations including inflammatory diseases, diabetes and genetic predisposition (3–6). Current cataract therapies include surgical extra-capsular lens fiber removal and synthetic lens implantation that can lead to secondary cataract (SC), also known as posterior capsular opacification in humans. In general, SC etiology includes the transdifferentiation of anterior capsule residual lens epithelial cells into mesenchymal myofibroblast cells (epithelial-mesenchymal transition [EMT]) that can migrate and expand into the posterior area of the lens capsule. The corresponding lens opacity results from EMT-associated changes in crystallin proteins, upregulation of cytoskeletal proteins such as α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and fibrotic extra-cellular matrix remodeling (7–9). In the pursuit of novel prevention and postsurgical therapies, numerous studies have focused on analyzing the etiology of SC formation, looking at the genetic predisposition and epigenetics as well as genomic and proteomic gene expression patterns (5,10,11). To study the detailed mechanism of SC, rodent cataract surgery models were successfully used, with lens epithelial cells undergoing SC during the initial days after lens fiber removal (12–14). Recently, we suggested that microRNA (miRNA)-dependent post-transcriptional regulation of lens development–associated genes might also play a role in lens regeneration (15). MicroRNAs are small proportional 22-nucleotide-long noncoding RNAs that regulate mRNA breakdown or translational interference of tissue-specific genes expressed during development, proliferation, differentiation and cell death mechanisms (16,17). RNA interference therapy was proposed as a therapeutic tool for a variety of clinical conditions (18–20). A recent study by Park et al. (21) proposed that specific targeting of SC-associated regulatory factors such as nuclear factorκB (NF-κB) by RNA interference might provide a promising tool for postsurgical prevention of SC-associated EMT. Correspondingly, this study uses a previously established mouse cataract surgery model for SC (12), microarray hybridization technology (22) and lens capsular bag culture to identify the miRNA expression pattern after cataract surgery and to determine the regulatory role of selective miRNAs, in particular miR-184 and miR-204, on SC etiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse Cataract Surgery

Cataract surgery was performed according to Suetsugu-Maki et al. and Medvedovic et al. (12,13,22) with modifications. C57BL/6 mice (8 wks old, female; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injections of ketamine and xylazine (95 and 14.3 mg/kg, respectively). For analgesia, buprenorphine (1 mg/kg) was give subcutaneously. The cornea was incised, and anterior capsulectomy was performed by removal of the lens core and fiber cells from the lens capsular bag. Capsular bags were washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing Mg2+ and Ca2+ to remove residual fiber cells. After 1, 2 and 3 wks of cataract surgery, mice were euthanized and eyeballs were removed to study SC formation. The posterior eyeballs were cut off and lens capsules were separated from the inside of the eyeball. For the control, intact lens capsules were collected from intact mouse eyes. The lens capsules were incubated in RNAlater® (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) at 4°C overnight, followed by storage of lens capsules at −80°C.

Microarray Analysis

Lens tissue was homogenized in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for total RNA isolation according to Trask et al. (23). Total RNA purity, quantity and quality were determined using a Nan-oDrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The miRNA was isolated from the total RNA preparation using the Flash Page™ gel system (Ambion). The purified miRNA was amplified using the NCode™ miRNA Amplification System (Invitrogen) from which the sense strand RNA was isolated using the PureLink™ Micro Kit (Invitrogen). The sense strand miRNA was labeled with cyanine-3 and used for hybridization on mouse miRNA microarray 8 × 15K slide version 2 containing probes for 627 mouse and 39 mouse γ herpes virus miRNAs from the Sanger database v 12.0 (Agilent Technologies). Agilent Feature Extraction software (24) depicted 55 miRNA probes that were detected on at least one out of four arrays by determination of the signal-to-error ratio. Intensity values for each individual time point were adjusted by setting negative values to “1.” Data are based on single values. Hierarchical clustering of mean centered intensities was employed using a Euclidean distance measure to generate a heat map for the 55 detectable probes using the open source software Cluster/Treeview. The software was written by Michael Eisen while at Stanford University.

Capsular Bag Culture

A radial incision was made at the border of the cornea and the sclera using a scalpel and scissors followed by lens extrusion using forceps. Lenses were washed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 (DMEM/F12, 1× antibiotics/antimycotics; Corning® cellgro®, Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA, USA), and any residual tissue on the outer lens capsule was removed supported by incubation in 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Cellgro) for 1–5 min. After submersion in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), the posterior capsule was positioned on a ring support structure at the base of the dish and the anterior capsule was opened by making three clockwise incisions, with incisions not extending the lens equator by keeping the lens positioned using forceps. The capsule was peeled from the lens fiber cell mass using small scissors, and the posterior capsule was pinned with the exterior facing the bottom of a 3-mm culture dish and the anterior edge forming a cuplike structure (capsular bag) using six entomological pins (D1; Watkins and Doncaster, Kent, UK). Residual lens fibers were removed by changing the medium to DMEM/F12 without FBS.

miRNA Target Prediction

Target binding sites for miR-184 and miR-204 were analyzed according to the current TargetScan (Bin3, Runx2, Meis2 [listed below]) and PicTar (Meis2 [listed below]) prediction programs. Regarding Mus musculus (mmu) miRNAs, TargetScan predicted conserved targets for mmu-miR-184 (18 conserved targets) and mmu-miR-204 (322 conserved targets) were screened to identify potential SC-associated genes listed by the AmiGO gene ontology database (http://amigo.geneontology.org) under the GO terms GO:0001837: epithelial to mesenchymal transition (http://amigo.geneontology.org/cgi-bin/amigo/term_details?term=GO:0001837&session_id=4145amigo1314025373) and GO:0002088: lens development in camera-type eye (http://amigo.geneontology.org/cgi-bin/amigo/term_details?term=GO:0002088&session_id=4145amigo1314025373). The identified genes were further analyzed for microarray-identified SC-associated miRNA binding sites using TargetScan accessed August 2011.

TargetScan predicted targets for mmu-miR-184 can be found at: http://www.targetscan.org/cgi-bin/targetscan/vert_50/targetscan.cgi?mirg=mmu-miR-184. TargetScan predicted targets for mmu-miR-204 can be found at: http://www.targetscan.org/cgi-bin/targetscan/vert_50/targetscan.cgi?species=Mouse&gid=&mir_c=&mir_sc=miR-204/211&mir_nc=&mirg=&sortType=cs&incl_nc=0. TargetScan 3′ untranslated regions (UTR) for Bin3 can be found at: http://www.targetscan.org/cgi-bin/targetscan/vert_50/view_gene.cgi?taxid=10090&gs=BIN3&showcnc=0&shownc=0. TargetScan 3′UTR for Runx2 can be found at: http://www.targetscan.org/cgi-bin/targetscan/vert_50/view_gene.cgi?taxid=10090&gs=RUNX2&showcnc=0&shownc=0#miR-204/211. TargetScan 3′UTR for Meis2 can be found at: http://www.targetscan.org/cgi-bin/targetscan/vert_50/view_gene.cgi?taxid=10090&gs=MEIS2&showcnc=0&shownc=0. To access PicTar 3′UTR for Meis2, use: http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de/cgi-bin/PicTar_vertebrate.cgi (search terms: has-miR-204, gene ID NM_172315).

Transfection of Capsular Bags

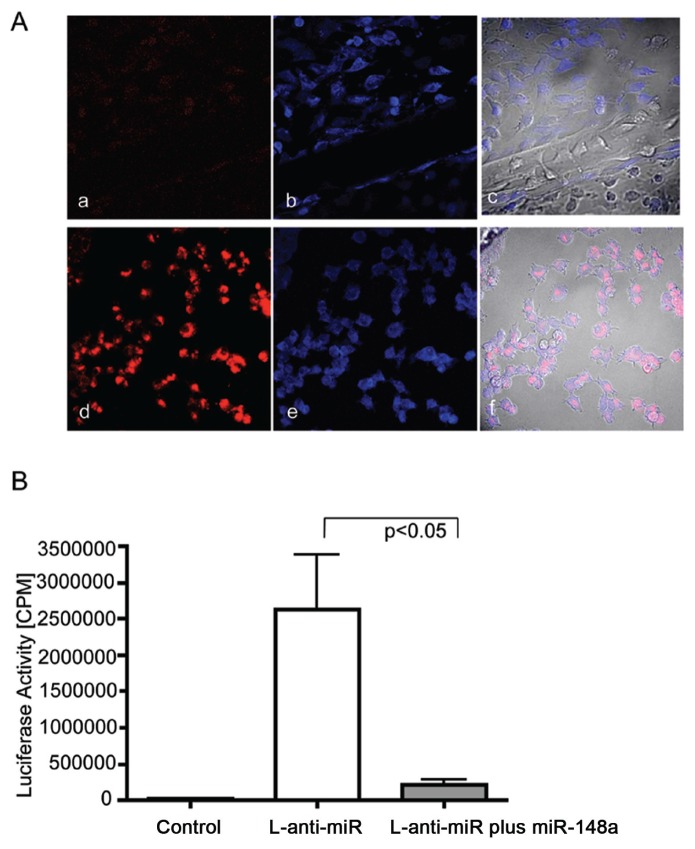

Capsular bag cultures were transfected using lipofectamine. Optimal transfection efficiency for miRNA constructs was determined before experiments by using the pMIR-REPORT luciferase system (Ambion). In brief, the pMIR-REPORT luciferase plasmid expressing luciferase mRNA fused to the antisense sequence for hsa-mir-148a cloned in the Spe1, and the HindIII multiple cloning site was transfected alone (L-anti-miR) or cotransfected with hsa-miR-148a (L-anti-miR plus miR-148a). Firefly luciferase activity was reported from cell lysates 48 h after transfec-tion according to the Promega Luciferase Assay System by detecting counts per minute (cpm) using a scintillation counter as previously published (15) (Figure 2). Cell lysates from nontransfected cells were used to measure background cpm (control). Samples were done in triplicate, and each sample included the average of 20 cpm measurements. Data were analyzed by unpaired Student t test, and P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance. Transfection efficiency of cy3-labeled anti-miR control (AM17011; Ambion) at different concentrations (for example, 5, 50 and 500 nmol/L) with or without lipofectamine was determined after 24 and 48 h of transfection by counting the number of cy3-labeled miRNAs localized within cell bodies (Figure 2). Human miR-184 inhibitor (anti-miR-184, AM10207), anti-miR control (AM17011), precursor miRNA for miR-204 (pre-miR-204, PM11116) and pre-miR control (AM17120), respectively, were mixed under optimized transfection conditions at a concentration of 50 μmol/L with 125 μL serum-free DMEM/F12 for 15 min and combined with the lipofectamine mixture under short vortexing and incubation for another 15–30 min. Proportional three to four capsular bag explants per 3-mm Petri dish were supplemented with serum-free DMEM/F12 and transfected with the corresponding mixture.

Figure 2.

Determination of miRNA transfection efficiency. (A) Determination of 48-h trans-fection efficiency by confocal microscopy. (a, b, c) Nontransfected control. (d, e, f) Cells transfected with cy3-labeled anti-miR control. (b, e) Cell bodies were labeled with TOTO-3 (blue staining). (c, f) Phase-contrast overlay with red and blue panels for detection of colocalization. The best transfection efficiency of proportional 85% was achieved at a concentration of 500 nmol/L for 48 h, visible as red staining within TOTO-3–stained cell bodies. (B) Determination of transfection efficiency by pMIR-REPORT™ luciferase system (Ambion). Graph demonstrates measured luciferase activity in cpm after 48 h transfec-tion in nontransfected (control) or MIR-REPORT™ luciferase plasmid expressing luciferase mRNA fused to the antisense sequence for hsa-mir-148a (L-anti-miR), or cotransfection of L-anti-miR with hsa-miR-148a (L-anti-miR plus miR-148a). Samples were done in triplicate, and each sample included the average of 20 cpm measurements. Data were analyzed by unpaired Student t test, and P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance. Error bars represent standard errors. Firefly luciferase activity was successfully inhibited within the cotransfected sample of L-anti-miR plus miR-148a (P < 0.05).

Migration and Cell Expansion

Imaging was performed using a TS100 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) under a phase-contrast setting with a charged-coupled device (CCD) camera (CoolSNAP cf2; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) and imaging software (Metamorph; Molecular Devices, Eugene, OR, USA). Percent cell confluence after capsular miRNA transfection was quantified from two different donor eyes after 24 and 48 h. The data were derived by dividing each capsular bag into four quadrants followed by measuring the average area of cells that migrated to the denuded area. Data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by entering the standard deviation of two donor eyes with four measurements each (representing four quadrants). P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance.

Immunohistochemistry

Imaging was performed using a TS100 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) under a fluorescence setting with a CCD camera (CoolSnapcf2) and imaging software (Metamorph). After the different transfection time periods, capsular bags were washed twice with PBS, followed by fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min and staining with primary mouse monoclonal antibody α-SMA 1:250 (Sigma-Aldrich). Integrated optical density of α-SMA expression after capsular bag transfection with miRNA constructs was quantified from two donor eyes (anti-miRNA constructs) and three donor eyes (pre-miRNA constructs) after 24, 48 and 72 h, respectively. The data were derived by dividing each capsular bag into four quadrants followed by measuring the integrated optical density of same-size panes in two different capsular locations (for example, the capsular edge and migration border). Data of anti-miRNA constructs were analyzed by two-way ANOVA by entering the standard deviation of two donor eyes with four measurements each (representing four quadrants). Data for pre-miRNA constructs were analyzed by unpaired Student t test and two-way ANOVA by entering the standard error from three donor eyes with four measurements each (representing four quadrants). P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance.

Protein Extraction

After lens extrusion, capsular bag culture was established by opening the posterior part of the lens capsule and pinning the anterior capsule with cells facing the interior of the capsular bag to preserve the maximum amount of lens epithelial cells for miRNA transfection. A total of four capsular bags were used per protein sample. To preserve all the cells contained in a sample, the growth medium containing supernatant was transferred to an Ep-pendorf tube. Capsular bag attached epithelial cells were detached by rigorous flushing with 750 μL PBS, followed by transfer of cells to the supernatant-containing tube. Proteins were extracted according to the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). In brief, after centrifugation at 2,000g and removal of the supernatant, cells were taken up in 25 μL Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent I (CER I), vortexed and incubated on ice for 10 min. After addition of CER II, samples were vortexed, incubated on ice for 1 min, vortexed and centrifuged at 13,000g for 5 min. The cytoplasmic supernatant was separated from the nuclear pellet. The nuclear pellet was dissolved in 15 μL Nuclear Extraction Reagent (NER), vortexed for 10 min and centrifuged at 13,000g for 5 min. The supernatant containing the nuclear fraction was pooled with the cytosolic fraction to obtain total cellular protein extracts.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western Blotting

The complete protein samples derived from four lenses each were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate– polyacrylamide gels and transferred to poly vinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. PVDF membranes were incubated with the primary polyclonal antibodies for bridging integrator 3 (BIN3) (ProteinTech Group, Chicago, IL, USA), Meis homeobox 2 (MEIS2) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), β-actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehy-drogenase (GAPDH) (loading control) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Staining with primary antibodies was followed by fluorescein-linked secondary antibody at 1:600 dilution and tertiary antibody anti-fluorescein AP conjugate 1:1,000 according to the enhanced chemifluorescence Western Blotting Kit (Amersham, Piscat-away, NY, USA), and membranes were scanned with a Biospectrum 500 Imaging System with an LM26 and BioChemi 500 Camera f/1.2 and Vision Works LS software. Antibody staining intensities were measured using ImageGauge 4.1 (Fuji Photo Film). Three samples per group with four lenses per sample were analyzed. Intensities of primary antibody staining were normalized to the β-actin or GAPDH loading controls through division. For comparison of controls versus miRNA treatments, a two-tailed unpaired Student t test was used. P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance.

All animal studies were approved by the University of Dayton Laboratory Animal Institutional Review Board.

All supplementary materials are available online at www.molmed.org.

RESULTS

Cataract Surgery for miRNA Expression Profiling

Previously, we demonstrated that SC can be modeled in mice by surgical removal of lens fibers from the capsular bag (12). The resulting lens regeneration after extra-capsular lens fiber removal consists of two critical phases. The initial phase is during the first week of regeneration and is marked by upregulation of EMT-specific extracellular matrix components, cytoskeletal proteins such as α-SMA and downregulation of crystallins. The second phase begins at wks 2 and 3 and is marked by an upregulation of lens structural proteins and lens differentiation (12,13). For the present study, 8-wk-old C57BL/6 mice underwent cataract surgery by capsulectomy, as previously described (12,13). Following 1, 2 and 3 wks after surgery, RNA was isolated from regenerating lenses to determine the miRNA expression profiles during these different time points.

Cataract Surgery Induces SC-Dependent Expression of miRNAs

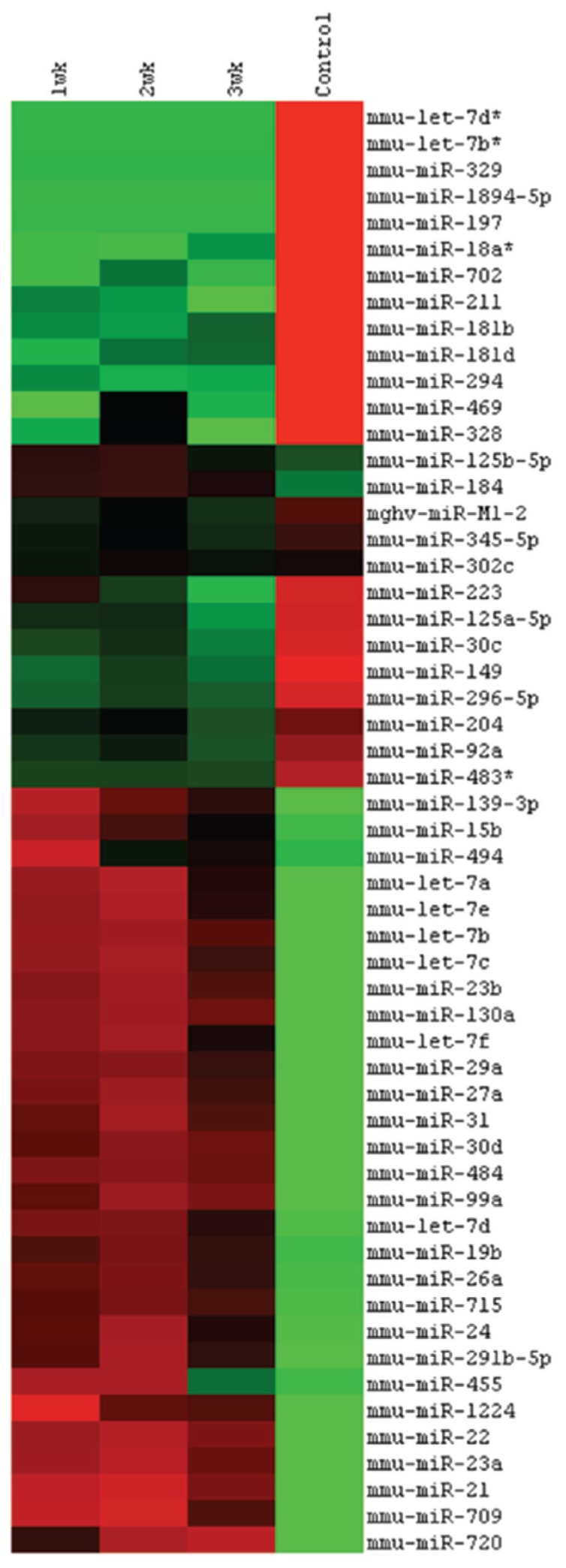

The broad-spectrum miRNA expression profile was examined by hybridizing miRNA probes to a microarray containing probes for 627 mouse miRNAs from the Sanger database v. 12.0. Microarray analysis revealed SC-associated changes in expression pattern of 55 regulatory miRNAs after mouse cataract surgery (Figure 1). A variety of lens development and regeneration-specific miRNAs (miR-31, miR-125b and a variety of the let-7/98 cluster, for example, let-7a, -7b, -7c, -7d, -7e and -7f) were upregulated after 1 wk of cataract surgery and declined to baseline levels over the 3-wk regeneration period (15,25–29). Regarding other lens-specific miRNAs (25), miR-184 demonstrated an upregulation after cataract surgery, whereas the miR-204/211 cluster demonstrated a downregulation after cataract surgery that continued declining over the 3-wk regeneration period. Further, several miRNAs such as miR-23a and miR-15b, that are known to play a role in regenerating retinal pigment epithelium, demonstrated a SC-associated upregulation (30). Similarly, SC-induced upregulation in common mediators of eye and neural crest development (for example, miR-23b and miR-130a) were identified (31). We also observed an upregulation of the proliferation inductive miR-22 after cataract surgery most likely corresponding to the SC-associated induction of lens epithelial (LE) cell migration and expansion (32). Regarding the detection of EMT-specific miRNAs, miR-21, miR-24 and miR-30d expression was upregulated, whereas miR-30c was downregulated in accordance with their role in induction of fibrotic proliferation and apoptosis (33–43).

Figure 1.

MicroRNA expression profile after cataract surgery. Dendrogram based on clustered miRNA intensity values to demonstrate the subtle differences of miRNA expression after different time points of cataract surgery. The intensities are mean centered, with red indicating values higher than the average of all four groups and green indicating lower values.

Capsular Bag Culture Using Anti-miR-184 and Pre-miR-204

The effect of miRNAs on SC etiology was studied in a capsular bag culture model that allows efficient manipulation of selective miRNA expression with faster outcomes compared with an animal surgery model and has been previously used by our group and others (13,44). SC characteristics can be observed within the first 3 d of capsular bag culture. When looking at miRNAs that demonstrate abundant expression in lens with a potential regulatory role in SC, miR-184 and miR-204 represent promising candidates (25). For instance, both of these miRNAs exhibit differential expression patterns during lens differentiation, regeneration and cataract etiology (25,27,45,46). In addition, these two miRNAs were previously identified to possess binding sites to the 3′UTRs of potential SC target mRNAs; for example, miR-184 targets the cataract-associated GTPase binding protein bridging integrator 3 [Bin3], and miR-204 targets the homeobox transcription factor Meis2 and canonical Wnt signaling associated transcription factor Runx2, respectively (29,47–49). In accordance with the SC observed opposing expression pattern of miR-204/211 versus miR-184 and our previous observations that demonstrated differential expression of miR-184 and miR-204 during iris cell dedifferentiation and lens regeneration in the adult newt (27), both of these miRNAs were selected for further investigation. To inhibit potential miR-184–dependent effects on SC formation that might result from the observed upregulation of miR-184 after cataract surgery, the miRNA inhibitor anti-miR-184 and the corresponding anti-miR control were chosen. Equivalent to the observed downregulation of miR-204/211 cluster after cataract surgery and with regard to the close sequence homology between miR-204 and miR-211, we simulated an overexpression of the miR204/211 cluster by transfection of pre-miR-204 precursor miRNA and the corresponding pre-miR control. Before miRNA transfection of capsular bag cultures, transfection efficiency was confirmed by microscopy and luciferase assay (see Figure 2 for detailed information).

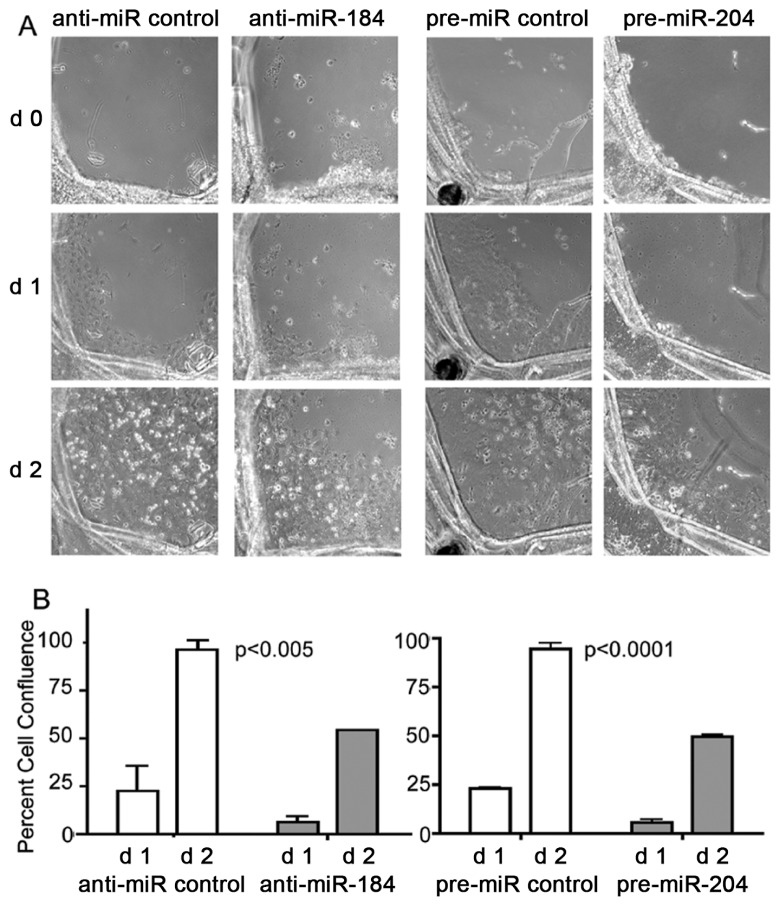

Attenuation of SC-Associated Cell Migration and Expansion by Anti-miR-184

Within a 3-d time period, all capsular bag cultures demonstrated SC characteristic migration and expansion of anterior LE cell from the capsular edge into the middle of the posterior capsular bag area. Anti-miR control transfected cultures demonstrated a 22.73% ± 12.74% confluence of capsular bags at d 1 and a 96.41% ± 5.06% confluence at d 2 (Figure 3), resulting in complete confluence at d 3 (data not shown). In contrast, anti-miR-184 attenuated migration and expansion of LE cells significantly (P < 0.005, two-way ANOVA) to 6.49% ± 3.23% confluence of capsular bags at d 1 and 54.36% ± 0.05% confluence at d 2.

Figure 3.

Attenuation of cell migration and expansion by anti-miR-184 and pre-miR-204. (A) Cell migration and expansion of LE cells within capsular bag cultures monitored by phase-contrast microscopy after 0–2 d treatment with anti-miR-184 compared with anti-miR control and pre-miR-204 compared with pre-miR control. (B) Graphs demonstrate percent cell confluence determined from d 1 and d 2 in (A) by measuring the average area of cells that migrated to the denuded area of the capsular bag. The data were derived by dividing each capsular bag into four quadrants followed by measuring the average area of cells that migrated to the denuded area. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA by entering the standard deviation from two donor eyes with four measurements each (representing four quadrants). Error bars represent standard deviations. P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance.

Attenuation of SC-Associated Cell Migration and Expansion by Pre-miR-204

Transfection with pre-miR control demonstrated a SC characteristic appearance of LE cell migration and expansion to the middle of capsular bags with 23.07% ± 0.34% cell confluence at d 1 and 94.66% ± 2.74% confluence at d 2 (see Figure 3), resulting in complete confluence at d 3 (data not shown). Transfec-tion with pre-miR-204 was comparable to observations with anti-miR-184, including a significant attenuation of LE cell migration and expansion (P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA) to 5.66% ± 1.32% confluence of capsular bags at d 1 and 49.74% ± 0.72% confluence at d 2.

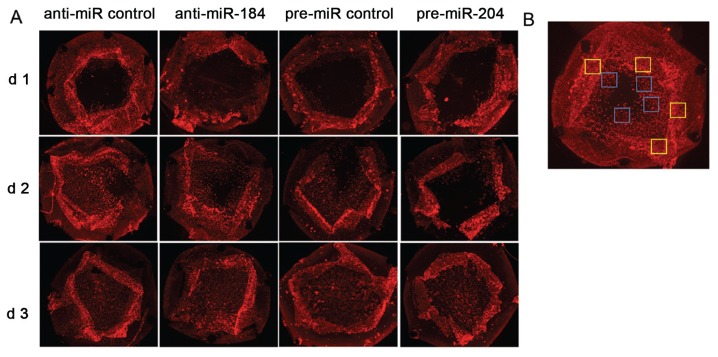

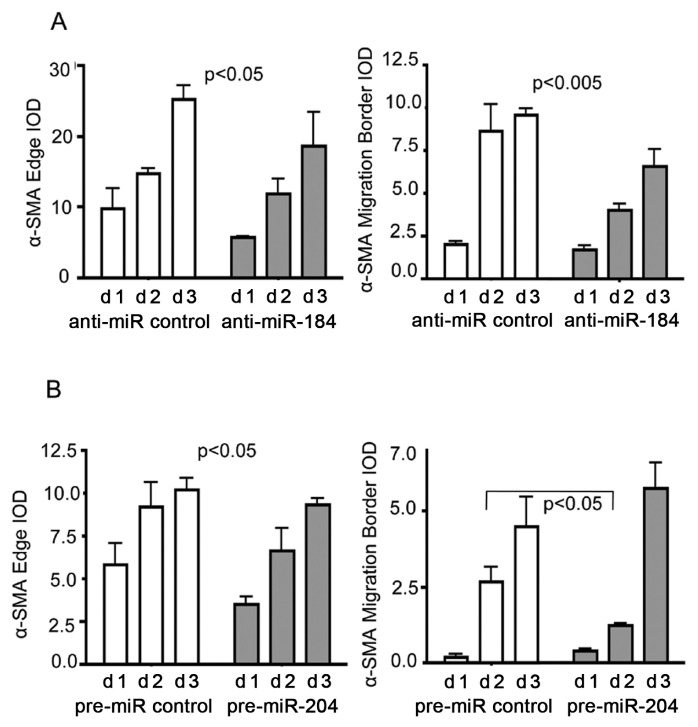

Attenuation of SC-Associated α-SMA Expression by Anti-miR-184

After 3 d, transfection of capsular bags with anti-miR-184, or anti-miR control expression of α-SMA, was analyzed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4). In general, α-SMA expression was mainly localized at capsular edges and migration borders and demonstrated an increasing α-SMA integrated optical density (IOD) over the 3-d time period in the presence of both anti-miR-184 and anti-miR control (compare Figure 4 and Figure 5A). In comparison to the control, anti-miR-184 demonstrated an attenuation of α-SMA expression at the capsular edge over the 3-d time period with an IOD of 5.79 ± 0.01 at d 1 (versus 9.71 ± 2.93, anti-miR control) and 18.55 ± 4.79 at d 3 (versus 25.16 ± 1.96, anti-miR control) (P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 5A). In addition, an attenuation of α-SMA expression could be observed at the migration border in the presence of anti-miR-184 with an IOD of 1.67 ± 0.29 at d 1 (versus 1.99 ± 0.18, anti-miR control) and 6.54 ± 1.04 at d 3 (versus 9.56 ± 0.36, anti-miR control) (P < 0.005, two-way ANOVA).

Figure 4.

Reduction of α-SMA expression after anti-miR-184 and pre-miR-204 treatment. (A) α-SMA expression within capsular bag cultures detected by immunohistochemistry after 1–3 d treatment with anti-miR-184 compared with anti-miR control and pre-miR-204 compared with pre-miR control. (B) Example image demonstrating areas for determination of IOD in Figure 5 at the capsular edge (yellow squares) and migration border (blue squares).

Figure 5.

Reduction of α-SMA expression after anti-miR-184 and pre-miR-204 treatment. Graph representing data analysis of α-SMA IOD derived from immunohistochemistry in Figure 4. α-SMA expression within capsular bag cultures detected by immunohistochemistry after 1–3 d treatment with anti-miR-184 compared with anti-miR control (A) and pre-miR-204 compared with pre-miR control (B). Data of anti-miRNA constructs were analyzed by two-way ANOVA by entering the standard deviation from two donor eyes with four measurements each (representing four quadrants). Error bars represent standard deviations. Data for pre-miRNA constructs were analyzed by unpaired Student t test and two-way ANOVA, by entering the standard error from three donor eyes with four measurements each (representing four quadrants). Error bars represent standard errors. P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance.

Attenuation of SC-Associated α-SMA Expression by Pre-miR-204

Similarly, 3-d transfection of capsular bags with either pre-miR-204 or pre-miR control demonstrated an increasing α-SMA expression at the capsular edges and migration borders (compare Figure 4 and Figure 5B). In com parison to the control, pre-miR-204 demonstrated an attenuation of α-SMA expression over the 3-d time period at the capsular edge with an IOD of 3.52 ± 0.44 at d 1 (versus 5.8 ± 1.24, pre-miR control) and 10.2 ± 0.66 at d 3 (versus 9.3 ± 0.38, pre-miR control) (P < 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 5B). Because capsular bags transfected with pre-miR-204 had reached complete confluence at d 3, the two-way ANOVA did not yield any conclusive results regarding temporal changes of α-SMA IOD over the 3-d time period. Thus, a significant attenuation of α-SMA expression could be observed at the migration border after 2 d transfection with pre-miR-204 with an IOD of 1.23 ± 0.07 versus 2.65 ± 0.5 (pre-miR control) (P < 0.05, Student t test).

Regulation of SC-Associated Target Expression by Anti-miR-184

One of the predicted miR-184 targets includes the mRNA for GTPase Bin3. The selective knockout of Bin3 was found to promote cataract formation in Bin3 knockout mice (29,50). Correspondingly, we hypothesized that the presence of anti-miR-184 might limit a potential miR-184–dependent downregulation of BIN3 expression during SC. Unexpectedly, Western blotting analysis demonstrated no changes in BIN3 protein expression after 1, 3 and 18 h capsular bag transfec-tion with anti-miR-184 (data not shown).

Regulation of SC-Associated Target Expression by Pre-miR-204

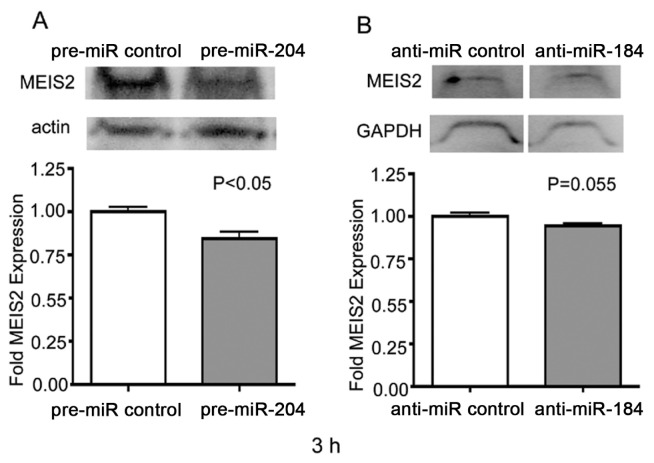

One of the predicted mRNA targets regulated by miR-204 includes the transcription factor MEIS2 (49,51–53). Previously, miR-204 downregulation and, correspondingly, MEIS2 upregulation was suggested to cause abnormal lens development in the Medaka fish (47). Accordingly, when testing upregulation of miR-204 by pre-miR-204, we expected a downregulation of MEIS2 expression. Western blotting demonstrated a 15% downregulation of MEIS2 after 3-h transfection of capsular bags with pre-miR-204 (P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). Interestingly, MEIS2 protein expression demonstrated a proportional 7% downregulation after a 3-h transfection of capsular bags with anti-miR-184 (P = 0.055), suggesting existence of a counterregulatory pathway between the two miRNAs miR-204 and miR-184 (Figure 6B). No changes of MEIS2 protein expression could be found at the earlier 1-h or later 18-h time point (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Attenuation of MEIS2 expression after pre-miR-204 and anti-miR-184 treatment. Western blot analysis of MEIS2 expression within LE cells after 3 h of pre-miR control or pre-miR-204 treatment (A) or anti-miR control or anti-miR-184 treatment (B). Blots were stained with the primary polyclonal antibodies for MEIS2 as well as β-actin or GAPDH (loading control). Graphs represent Image Gage 4.1 densitometric analysis of MEIS2 expression ratio in the upper panel. Three samples per group with four lenses per sample were analyzed. Intensities of MEIS2 were normalized to the β-actin or GAPDH loading controls through division. For comparison of controls versus miRNA treatments, a two-tailed unpaired Student t test was used. Error bars represent standard errors. P < 0.05 was used as a criterion for significance.

Besides Meis2, miR-204 was predicted to regulate other EMT-associated target mRNAs such as Smad4 and cell cycle regulators Cdc7, Cdc25b, E2f3 and Runx2 (48,54,55). According to our previous study that demonstrated an attenuation of SC-associated Runx2 mRNA expression in the presence of complement receptor C5 antagonist after 1 wk of cataract surgery, Runx2 was chosen as an additional target for pre-miR-204 treatment (13). In contrast to an expected attenuation of RUNX2, no changes in RUNX2 protein levels could be detected in the presence of miR-204 at the different time points of 1, 3 and 18 h of capsular bag culture (data not shown).

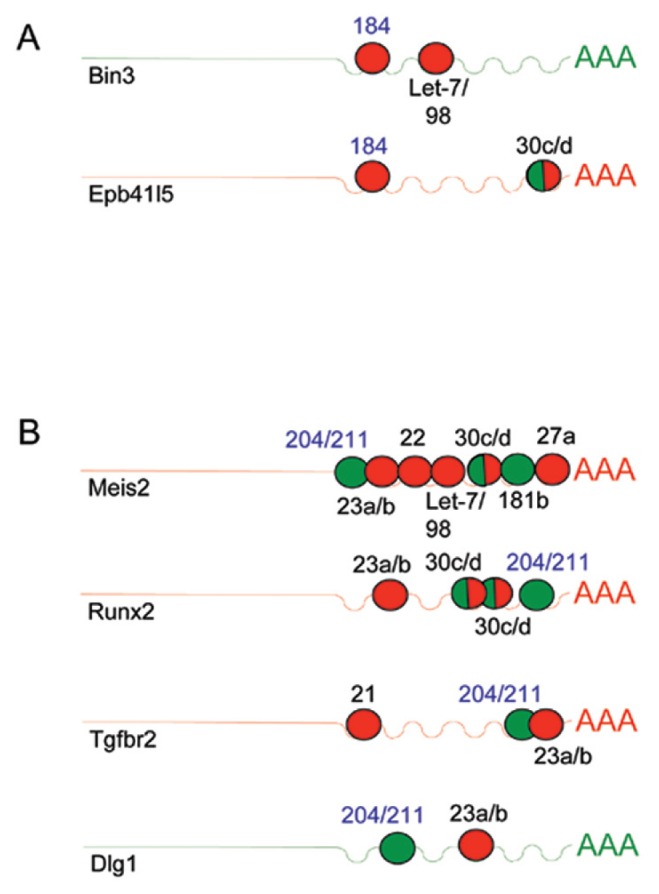

Bioinformatic Analysis of MiR-184 and MiR-204 Target 3′UTR Reveals Multiple Binding Sites of Other Competitive miRNAs

To explain these results, we performed a detailed bioinformatic analysis of all potential SC-associated mRNAs that are targeted by miR-184 or miR-204. We find that several of these target mRNAs contain 3′UTR binding sites for miRNAs, with opposing expression patterns during SC, which alludes to the existence of a complex network (Figure 7). For example, Bin3 mRNA demonstrates 3′UTR binding sites for miR-184 but also for miRNAs of the Let-7/98 cluster, which are also upregulated during SC (Figure 7A). Thus, the Let7 miRNA members might render a potential anti-miR-184 targeting of Bin3 ineffective. Likewise, mRNAs for Meis2 and Runx2 contain many other competitive miRNAs binding sites in their 3′UTR besides miR-204, suggesting that a potential downregulation by miR-204 might be rendered ineffective as well (Figure 7B) (see Discussion for more details on the possible regulation).

Figure 7.

MicroRNA 184 and 204 competitive RNA network during SC-associated EMT. Schematic diagram demonstrating binding patterns of SC-associated miRNAs to the 3′UTR of potential SC expressed target mRNAs. Target mRNAs are shown for mmu-miR-184 (A) and mmu-miR-204 (B) identified by TargetScan predictions followed by screening for potential SC-associated genes that play a role during EMT listed by the AmiGO gene ontology under the GO terms GO:0001837:epithelial to mesenchymal transition and GO:0002088: lens development in camera-type eye. MicroRNA 3′UTR binding sites are demonstrated in circles with numbers depicting the specific type of microRNA. SC-associated microRNA upregulation is indicated by red circles and downregulation by green circles. SC-associated target mRNA upregulation is in red and down-regulation is in green.

In summary, the results conclude that miR-184 and miR-204 play a significant role in the control of SC etiology in mice and are most likely regulated through a complex networking with other miRNAs.

DISCUSSION

Role of miRNAs in Attenuation of SC

Posttranscriptional RNA interference through miRNA or small interfering RNA (siRNA) represents a new therapeutic tool for treatment of cancer, cardiovascular disease, fibrosis and antiviral therapy (56–59). Recently, the group of Park et al. further confirmed the suitability of RNA interference therapy for treatment of SC (21). Accordingly, this study focused on identifying the SC-associated miRNA expression pattern after cataract surgery using microarray technology. The identified miRNA expression pattern included 55 miRNAs with different ontologies, for example, regulation of cell growth, differentiation and development, EMT-dependent fibrosis and lens development and cataract. Interestingly, when looking at changes in lens-specific miRNAs, miR-184 demonstrated a SC- associated upregulation in comparison to an observed downregulation of the miR-204/211 cluster (25). These miRNAs have also been identified to play a role during iris cell dedifferentiation and lens regeneration in the adult newt, supporting a potential lens-regenerative function (27). Having in mind the potential therapeutic role of miRNAs in prevention of SC, these two selected miRNAs have predicted binding sites to the 3′UTR of cataract-associated target mRNAs, for example, the GTPase binding protein Bin3, the homeobox transcription factor Meis2 and canonical Wnt signaling associated transcription factor Runx2, respectively (29,47,48). Correspondingly, miRNA-associated counterregulation of these EMT-associated target mRNAs might prevent formation of SC.

Evidence of SC Attenuation by Anti-miR-184 and Pre-miR-204

We found clear evidence that both anti-miR-184 and pre-miR-204 can attenuate SC within the capsular bag model, supporting the SC regulatory role of these two miRNAs. Both of these miR-NAs were able to attenuate anterior LE cell migration and expansion from the capsular edge into the middle of the posterior capsular bag area with a proportional 3.5-/4-fold decrease of cell confluence at d 1 and 1.8-/1.9-fold decrease at d 2. This result is further supported by attenuation of α-SMA expression with a proportional 1.4-fold downregulation of α-SMA IOD at the capsular edge and a proportional twofold downregulation of α-SMA IOD at the migration border over the 3-d time period in the presence of anti-miR-184 or pre-miR-204.

Bioinformatic Analysis of miR-184 Target 3′UTR Reveals Multiple Binding Sites of Other Competitive miRNAs

One explanation for the insufficient regulation of BIN3 expression by anti-miR-184 targeting is the existence of other competitive miRNA binding sites within the 3′UTR of Bin3 mRNA. For instance, TargetScan (http://targetscan.org) predictions identify a binding site for miR-184 at the position 264–270 of the Bin3 3′UTR, thus also predicting a binding site for the let-7/98 cluster at position 348–354 (compare the Bin3 Web address in the Materials and Methods section and Figure 7A). Because of the observed upregulation of most let-7/98 cluster members, the intended miR-184 attenuation by anti-miR-184 might not be sufficient in preventing a potential SC-associated downregulation of BIN3.

Including Bin3 TargetScan predicted a total of 18 mmu-miR-184–specific target mRNAs, suggesting that the observed SC attenuation might also include miR-184–dependent regulation and targeting of other mRNAs (compare to the mmu-miR-184 Web address in Materials and Methods).

Bioinformatic Analysis of miR-204 Target 3′UTR Reveals Multiple Binding Sites of Other Competitive miRNAs

Besides binding of miR-204/211 at position 3770–3776 within the 3′UTR of Runx2, TargetScan predictions identify multiple other miRNA binding sites, including the mir23a/b cluster at position 996–1002 and two miR-30c/d clusters at position 3445–3451 and position 3456–3462 (compare the Runx2 Web addresses in Materials and Methods and Figure 7B). In accordance with the SC-associated up-regulation of miR-30d and the miR-23a/b cluster, the pre-miR-204–dependent effect on Runx2 target mRNA expression might be rendered ineffective.

Similarly, the PicTar Web interface (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de) predicts multiple other miRNA binding sites for the Meis2 3′UTR besides miR-204/211, including SC upregulated miR-23a/b, miR-27a and the let-7/98 cluster, as well as miR-181b. In contrast to older TargetScan predictions, the current parameters of TargetScan do not include any defined target binding site for the miR-204/211 cluster within the Meis2 3′UTR. Thus, current TargetScan predictions for Meis2 match the PicTar predictions regarding binding sites for miR-23a/b, miR-27a and the let-7/98 cluster, but also include miR-22, miR-30d and SC downregulated miR-30c (compare the Meis2 Web addresses in Materials and Methods and Figure 7B). Correspondingly, the potential competition of these other Meis2-specific miRNAs with miR-204– dependent regulation of MEIS2 expression, might account for the limited 15% downregulation of MEIS2 by pre-miR-204 in our experiment.

Including Meis2 and Runx2 TargetScan predicted a total of 322 mmu-miR-204–specific target mRNAs, suggesting that miR-204 regulation of other mRNAs might also be relevant for the observed SC attenuation (compare to the mmu-miR-204 Web address in Materials and Methods).

Bioinformatic Analysis of miR-184 and miR-204 Target Gene Ontology Database Reveals a Complex miRNA Network

To support the suggestion that miR-184 might regulate other SC-associated target mRNAs besides Bin3, the 18 TargetScan–predicted miR-184 targets were screened for a potential match with genes listed by the AmiGO gene ontology database (http://amigo.geneontology.org) under the GO terms GO:0001837: epithelial to mesenchymal transition and GO:0002088:lens development in camera-type eye. Besides Bin3, two other potential miR-184 target mRNAs, for example, eye development–associated factors Epb41l5 and Zic4, were identified by this method (60,61) (Figure 7A and Supplementary Figure 1A). Interestingly, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β–dependent upregulation of EPB41L5 participates in posttranscriptional regulation of cadherin and integrin important for EMT during mouse gastrulation. Thus, the role of EPB41L5 in SC-associated EMT in adult mice remains to be determined (62).

Similarly, the 322 TargetScan predicted miR-204 targets were screened for a potential match with genes listed by the AmiGO gene ontology database (http://amigo.geneontology.org) under the GO terms GO:0001837 and GO:0002088. Besides Meis2 and Runx2, nine potential SC-associated miR-204 target mRNAs were identified. For instance, the miR-204 targets Meis1, Wnt4, Foxc1, Hnrnpa2b1, Tfap2a, Mafg and Sox1 represent important factors in regulation of eye development (63–69) (Figure 7B and Supplementary Figure 1B). In addition, the two identified miR-204 targets Dlg1 and Tgfbr2 represent some potential candidates for regulation of SC-dependent EMT (70–72). For instance, upregulation of TGF-β2 receptors (TGFBR2) can be found in regenerating lens epithelial cells after UVB irradiation (72). In addition, DLG1 downregulation was associated with EMT in a mouse ocular tumor model (70).

Interestingly, when looking at expression of SC-associated miRNAs in correlation with binding to miR-204 target mRNAs, mRNAs of the major developmental factors, for example, Wnt4, Foxc1 and Hnrnpa2b, are solely regulated by miR-204/211 with two binding sites of miR-204/211 within the 3′UTR of Wnt4 (Supplementary Figure 1B). In contrast, 3′UTRs of Tfap2a and Sox11 seem to be coregulated by miR-204/211 and miR-92a. In addition, 3′UTRs of Meis2, Runx2, Tgfbr2, Dlg1, Meis1 and Sox11 share binding sites for the miR-23a/b cluster, suggesting a miR-204 counterregulatory function of miR-23a/b. Further common miRNA binding sites include the let-7/98 cluster in the 3′UTR of Bin3 and Meis2 and the miR-30c/d cluster in the 3′UTR of Epb41l5 and Zic4 as well as Meis2, Runx2 and Mafg. These findings further support existence of a competitive miRNA network for target mRNAs regulated by miR-184 and miR-204.

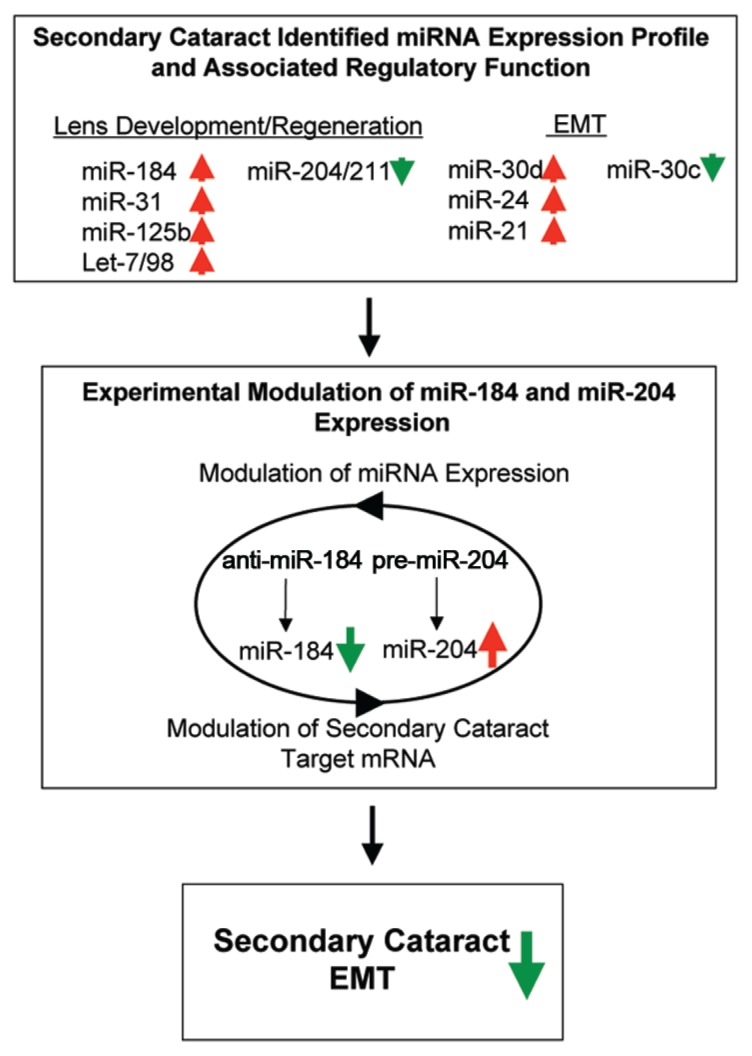

CONCLUSION

In summary, our study demonstrates the complex miRNA network interactions during formation of SC in mice. Although the tested miRNAs, for example, anti-miR-184 and pre-miR-204, achieved a partial attenuation of SC-associated EMT, most likely, the mechanistic interplay of these miRNAs with potential SC target mRNAs and other co-or counterregulatory miRNAs needs to be considered (see Figure 8 for further explanation). Such miRNA networks have previously been suggested by our group and others, including a recent hypothesis that underlines the existence of a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network (15,73–75). With this in mind, our study opens new avenues for future studies that target the competitive miRNA network for SC therapy and other diseases.

Figure 8.

Summary diagram of miR-184 and miR-204 competitive RNA network in control of mouse secondary cataract. The SC-determined broad-spectrum miRNA expression profile revealed changes in expression patterns of major lens differentiation/regeneration-and EMT-associated miRNAs (upregulation indicated with red arrows and downregulation indicated with green arrows). Accordingly, the microRNAs miR-184 and miR-204 were chosen for further analysis because of their differential expression patterns during SC that can also be observed during lens differentiation, regeneration and cataract etiology (25,27,34,35). The experimental manipulation of miRNA expression by the anti-miR-184–dependent downregulation of miR-184 and pre-miR-204–dependent upregulation of miR-204 is suggested to result in the mechanistic interplay with other co-or counterregulatory miRNAs for the modulation of potential SC target mRNAs and attenuation of SC EMT. Vice versa, the miRNA-dependent modulation of SC target mRNAs might include alterations in transcription factors relevant for expression of SC EMT attenuating miRNAs.

Supplemental Data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant EY16707 to PA Tsonis.

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li Z, Cui H, Zhang L, Liu P, Bai J. Prevalence of and associated factors for corneal blindness in a rural adult population (the southern Harbin eye study) Curr Eye Res. 2009;34:646–51. doi: 10.1080/02713680903007139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein BE, Klein R, Linton KL. Prevalence of age-related lens opacities in a population: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:546–52. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31934-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blakely EA, et al. Radiation cataractogenesis: epidemiology and biology. Radiat Res. 2010;173:709–17. doi: 10.1667/RRXX19.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies MJ, Truscott RJ. Photo-oxidation of proteins and its role in cataractogenesis. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63:114–25. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiels A, Bennett TM, Hejtmancik JF. Cat-Map: putting cataract on the map. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2007–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao GN, Khanna R, Payal A. The global burden of cataract. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:4–9. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283414fc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saika S, et al. TGF beta in fibroproliferative diseases in the eye. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2009;1:376–90. doi: 10.2741/S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark JI, Matsushima H, David LL, Clark JM. Lens cytoskeleton and transparency: a model. Eye (Lond) 1999;13:417–24. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ihanamaki T, Pelliniemi LJ, Vuorio E. Collagens and collagen-related matrix components in the human and mouse eye. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23:403–34. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saika S, et al. Fibrotic disorders in the eye: targets of gene therapy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:177–96. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cvekl A, Mitton KP. Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms in vertebrate eye development and disease. Heredity. 2010;105:135–51. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Call MK, Grogg MW, Del Rio-Tsonis K, Tsonis PA. Lens regeneration in mice: implications in cataracts. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:297–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suetsugu-Maki R, et al. A complement receptor C5a antagonist regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition and crystallin expression after lens cataract surgery in mice. Mol Vis. 2011;17:949–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lois N, et al. Effect of TGF-beta2 and anti-TGF-beta2 antibody in a new in vivo rodent model of posterior capsule opacification. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4260–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura K, et al. miRNAs in newt lens regeneration: specific control of proliferation and evidence for miRNA networking. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaucsar T, Racz Z, Hamar P. Post-transcriptional gene-expression regulation by micro RNA (miRNA) network in renal disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinkel R, Trenkwalder T, Kupatt C. Gene therapy for ischemic heart disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:723–37. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.570749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oba S, et al. miR-200b precursor can ameliorate renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park HY, et al. Effects of nuclear factor-kappaB small interfering RNA on posterior capsule opacification. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:4707–15. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medvedovic M, Tomlinson CR, Call MK, Grogg M, Tsonis PA. Gene expression and discovery during lens regeneration in mouse: regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition and lens differentiation. Mol Vis. 2006;12:422–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trask HW, et al. Microarray analysis of cytoplasmic versus whole cell RNA reveals a considerable number of missed and false positive mRNAs. RNA. 2009;15:1917–28. doi: 10.1261/rna.1677409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahurak M, et al. Pre-processing Agilent microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan DG, Oliveira-Fernandes M, Lavker RM. MicroRNAs of the mammalian eye display distinct and overlapping tissue specificity. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen J, et al. MicroRNAs regulate ocular neovascularization. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1208–16. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsonis PA, et al. MicroRNAs and regeneration: Let-7 members as potential regulators of dedifferentiation in lens and inner ear hair cell regeneration of the adult newt. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:940–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frederikse PH, Donnelly R, Partyka LM. miRNA and Dicer in the mammalian lens: expression of brain-specific miRNAs in the lens. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;126:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian L, Huang K, DuHadaway JB, Prendergast GC, Stambolian D. Genomic profiling of miRNAs in two human lens cell lines. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35:812–8. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2010.489182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutty RK, et al. MicroRNA expression in human retinal pigment epithelial (ARPE-19) cells: increased expression of microRNA-9 by N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide. Mol Vis. 2010;16:1475–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gessert S, Bugner V, Tecza A, Pinker M, Kuhl M. FMR1/FXR1 and the miRNA pathway are required for eye and neural crest development. Dev Biol. 2010;341:222–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ting Y, Medina DJ, Strair RK, Schaar DG. Differentiation-associated miR-22 represses Max expression and inhibits cell cycle progression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:606–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, et al. MicroRNA miR-24 inhibits erythropoiesis by targeting activin type I receptor ALK4. Blood. 2008;111:588–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Q, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta-regulated miR-24 promotes skeletal muscle differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2690–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan MC, et al. Molecular basis for antagonism between PDGF and the TGFbeta family of signalling pathways by control of miR-24 expression. EMBO J. 2010;29:559–73. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng AM, Byrom MW, Shelton J, Ford LP. Antisense inhibition of human miRNAs and indications for an involvement of miRNA in cell growth and apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1290–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoover LL, Kubalak SW. Holding their own: the noncanonical roles of Smad proteins. Sci. Signal. 2008;1:pe48. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.146pe48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu G, et al. miR-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1589–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao Q, et al. Micro-RNA-21 regulates TGF-beta-induced myofibroblast differentiation by targeting PDCD4 in tumorstroma interaction. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1783–92. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Lee CG. MicroRNA and cancer: focus on apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:12–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozcan S. MiR-30 family and EMT in human fetal pancreatic islets. Islets. 2009;1:283–5. doi: 10.4161/isl.1.3.9968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duisters RF, et al. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;104:170–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joglekar MV, et al. The miR-30 family mi-croRNAs confer epithelial phenotype to human pancreatic cells. Islets. 2009;1:137–47. doi: 10.4161/isl.1.2.9578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wormstone IM, Wang L, Liu CS. Posterior capsule opacification. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:257–69. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Conte I, et al. miR-204 is required for lens and retinal development via Meis2 targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:15491–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914785107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hughes AE, et al. Mutation altering the miR-184 seed region causes familial keratoconus with cataract. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:628–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conte I, et al. miR-204 is required for lens and retinal development via Meis2 targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15491–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914785107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang J, Zhao L, Xing L, Chen D. Micro-RNA-204 regulates Runx2 protein expression and mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2010;28:357–64. doi: 10.1002/stem.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X, Friedman A, Heaney S, Purcell P, Maas RL. Meis homeoproteins directly regulate Pax6 during vertebrate lens morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2097–107. doi: 10.1101/gad.1007602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramalingam A, et al. Bin3 deletion causes cataracts and increased susceptibility to lymphoma during aging. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1683–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bumsted-O’Brien KM, Hendrickson A, Haverkamp S, Ashery-Padan R, Schulte D. Expression of the homeodomain transcription factor Meis2 in the embryonic and postnatal retina. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505:58–72. doi: 10.1002/cne.21458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heine P, Dohle E, Bumsted-O’Brien K, Engel-kamp D, Schulte D. Evidence for an evolutionary conserved role of homothorax/Meis1/2 during vertebrate retina development. Development. 2008;135:805–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.012088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Karali M, et al. miRNeye: a microRNA expression atlas of the mouse eye. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:715. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuokkanen S, et al. Genomic profiling of microRNAs and messenger RNAs reveals hormonal regulation in microRNA expression in human endometrium. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:791–801. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.081059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arora A, et al. Prediction of microRNAs affecting mRNA expression during retinal development. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hemida MG, Ye X, Thair S, Yang D. Exploiting the therapeutic potential of microRNAs in viral diseases: expectations and limitations. Mol Diagn Ther. 2010;14:271–82. doi: 10.1007/BF03256383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jamaluddin MS, et al. miRNAs: roles and clinical applications in vascular disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2011;11:79–89. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gandellini P, Profumo V, Folini M, Zaffaroni N. MicroRNAs as new therapeutic targets and tools in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:265–79. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.550878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang X, Tsitsiou E, Herrick SE, Lindsay MA. MicroRNAs and the regulation of fibrosis. FEBS J. 2010;277:2015–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Christensen AK, Jensen AM. Tissue-specific requirements for specific domains in the FERM protein Moe/Epb4.1l5 during early zebra -fish development. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horng S, et al. Differential gene expression in the developing lateral geniculate nucleus and medial geniculate nucleus reveals novel roles for Zic4 and Foxp2 in visual and auditory pathway development. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13672–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2127-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirano M, Hashimoto S, Yonemura S, Sabe H, Aizawa S. EPB41L5 functions to post-transcriptionally regulate cadherin and integrin during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1217–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hisa T, et al. Hematopoietic, angiogenic and eye defects in Meis1 mutant animals. EMBO J. 2004;23:450–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wan X, et al. Negative feedback regulation of Wnt4 signaling by EAF1 and EAF2/U19. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Acharya M, Huang L, Fleisch VC, Allison WT, Walter MA. A complex regulatory network of transcription factors critical for ocular development and disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1610–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fang X, et al. Landscape of the SOX2 protein-protein interactome. Proteomics. 11:921–934. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Dosari MS, et al. Ocular manifestations of branchio-oculo-facial syndrome: report of a novel mutation and review of the literature. Mol Vis. 2010;16:813–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lecoin L, Sii-Felice K, Pouponnot C, Eychene A, Felder-Schmittbuhl MP. Comparison of maf gene expression patterns during chick embryo development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wurm A, Sock E, Fuchshofer R, Wegner M, Tamm ER. Anterior segment dysgenesis in the eyes of mice deficient for the high-mobility-group transcription factor Sox11. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:895–907. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vieira V, et al. Differential regulation of Dlg1, Scrib, and Lgl1 expression in a transgenic mouse model of ocular cancer. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2390–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nguyen MM, et al. Requirement of PDZ-containing proteins for cell cycle regulation and differentiation in the mouse lens epithelium. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8970–81. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.8970-8981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osada H, et al. Ultraviolet B-induced expression of amphiregulin and growth differentiation factor 15 in human lens epithelial cells. Mol Vis. 2011;17:159–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tuccoli A, Poliseno L, Rainaldi G. miRNAs regulate miRNAs: coordinated transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2473–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146:353–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Seitz H. Redefining microRNA targets. Curr Biol. 2009;19:870–3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.