Abstract

Trait impulsivity is a reliable, robust predictor of risky, problematic alcohol use. Mounting evidence supports a multidimensional model of impulsivity, whereby several distinct traits serve as personality pathways to rash action. Different impulsivity-related traits may predispose individuals to drink for different reasons (e.g., to enhance pleasure, to cope with distress) and these different motives may, in turn, influence drinking behavior. Previous findings support such a mediational model for two well-studied traits: sensation seeking and lack of premeditation. This study addresses other impulsivity-related traits, including negative urgency. College students (N = 432) completed questionnaires assessing personality, drinking motives, and multiple indicators of problematic drinking. Negative urgency, sensation seeking, and lack of premeditation were all significantly related to problematic drinking. When drinking motives were included in the model, direct effects for sensation seeking and lack of premeditation remained significant, and indirect effects of sensation seeking and lack of premeditation on problematic drinking were observed through enhancement motives. A distinct pathway was observed for negative urgency. Negative urgency bore a significant total effect on problematic drinking through both coping and enhancement motives. This study highlights unique motivational pathways through which different impulsive traits may operate, suggesting that interventions aimed at preventing or reducing problematic drinking should be tailored to individuals' personalities. For instance, individuals high in negative urgency may benefit from learning healthier strategies for coping with distress.

Keywords: impulsivity, urgency, drinking motives, alcohol

1. Introduction

Trait impulsivity is a robust predictor of alcohol abuse. A broad and growing literature suggests that impulsivity is not a unitary construct, but rather reflects multiple facets of personality that each contribute to rash and potentially dangerous behavior, such as hazardous, problematic drinking. It is important to understand the proximal mechanisms by which these distinct personality traits exert their effects on behavior. Drinking motives, or the reasons people say they engage in alcohol use, offer one such intermediate mechanism and have been reliably linked to drinking habits and alcohol-related problems. Interestingly, while the mediating role of drinking motives has been examined with some impulsivity-related traits, no studies have considered how motives may mediate the relation between urgency and problematic alcohol use. The current study aims to address this gap in the literature.

1.1. Multiple Personality Pathways to Impulsive, Risky Behavior

Impulsivity has traditionally been understood as a tendency to act rashly or without adequate forethought. However, consensus is lacking on how best to define impulsivity, and many theories of general personality (Buss & Plomin, 1975; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985; Zuckerman, 1994) and of impulsivity specifically (Dickman, 1990; Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) have defined the construct as multidimensional in nature. To address substantial variability in how impulsivity was conceptualized and assessed, Whiteside and Lynam (2001) performed a factor analysis using responses to several prominent measures purported to tap aspects of impulsive personality. They arrived at a four-factor model of impulsive personality, which was used to develop the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). The first trait in the UPPS model, (lack of) premeditation, refers to the tendency to act without planning or without adequate consideration of potential outcomes. This trait most closely resembles the traditional, “prototypical” definition of impulsivity. The second trait, sensation seeking, refers to the tendency to enjoy and to pursue exciting or novel experiences, even if those situations are dangerous or risky. The third trait, (lack of) perseverance, refers to an inability to remain focused on boring or difficult tasks. The fourth trait, urgency, refers to the tendency to experience and act upon impulses, frequently while experiencing strong affect. Recently, a distinction has been drawn between negative urgency and positive urgency (Cyders & Smith, 2007), where negative urgency is associated with impulsive behavior under conditions of negative affect (e.g., anger, anxiety) and positive urgency is expressed under conditions of positive affect (e.g., joy, elation). Individuals high in negative urgency in particular may engage in impulsive behaviors as a way of alleviating negative affect in the short term, despite the potential for negative long-term consequences. Alternatively, the presence of strong emotions may lead to a general disinhibition of behavior, where the response does not necessarily serve an instrumental or coping function.

Supporting the utility of this model, the UPPS facets demonstrate unique relations with a variety of alcohol-related outcomes. For example, lack of premeditation relates positively with heavy alcohol use (Carlson, Johnson, & Jacobs, 2010; Lynam & Miller, 2004; Miller, Flory, Lynam, & Leukefeld 2003), and alcohol dependence (Verdejo-Garcia, Bechara, Recknor, & Perez-Garcia, 2007). Sensation seeking has been shown to relate positively with drug and alcohol use (Carlson et al., 2010; Horvath, Milich, Lynam, Leukefeld, & Clayton, 2004; Puente, Gutiérrez, Abellán, & López, 2008; Schepis et al., 2008) and heavy alcohol use (Fischer & Smith, 2008; Lynam & Miller, 2004) among adolescents and college students. Urgency has also been linked consistently to alcohol abuse and drinking-related problems (Settles, Cyders, & Smith, 2010; Magid & Colder, 2007; Verdejo-Garcia et al., 2007), indicating that urgency may be more strongly linked to hazardous drinking rather than typical patterns of alcohol use. Lack of perseverance demonstrated mixed relations with risky behaviors, including alcohol use and problems (e.g., Fischer & Smith, 2008; Lynam & Miller, 2004; but see also Magid & Colder, 2007; Verdejo-Garcia et al., 2007). Taken together, these findings warrant examination of the specific roles of lack of premeditation, sensation seeking, and urgency when considering relations between personality and risky, problematic alcohol use. Therefore, models that only include traits resembling lack of premeditation and sensation seeking are incomplete and neglect the important relation between urgency and problematic drinking.

1.2. Motives as Mediators of the Personality-Behavior Relation

The differing natures of the impulsivity-related traits suggests that each may operate through distinct proximal mechanisms to influence behavior. Examining the reasons why individuals engage in alcohol use, or drinking motives (Cooper, 1994) may allow for a better understanding of how certain personality traits put individuals at risk for hazardous or problematic drinking. The Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994) is a widely used measure of drinking motives. The DMQ was developed based on the notion that motives vary both in valence (positive versus negative) and in source (internal versus external) (Cox & Klinger, 1988). Considering these two dimensions yields four motives an individual might have for drinking. Coping motives are associated with drinking in order to reduce or cope with negative affect; this reflects an internal, negative-reinforcement drinking motive. Enhancement motives are associated with drinking in order to increase positive mood; this reflects an internal, positive-reinforcement drinking motive. Conformity motives are associated with drinking in order to avoid negative social consequences (e.g. not fitting in); this reflects an external, negative-reinforcement motive. Social motives are associated with drinking in order to obtain social rewards (e.g. having fun with friends); this reflects an external, positive- reinforcement motive. These four types of motives—coping, enhancement, conformity and social—are consistent with the reasons for drinking identified by other researchers (Carpenter & Hasin, 1998) and with models suggesting the importance of distinguishing between positive and negative reinforcement motives for drinking (Farber, Khavari, & Douglass, 1980).

Prior findings indicate that these motives are reliable predictors of problematic drinking. Both enhancement and coping motives, in particular, tend to predict alcohol-related problems (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche, Stewart, & Cooper, 2008; Merrill & Read, 2010). Social motives for drinking are the most commonly endorsed motives in non-clinical populations (e.g. college students), but associations with alcohol-related outcomes yield different conclusions across studies (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche, Stewart, et al., 2008; Merrill & Read, 2010). Conformity motives typically do not relate to alcohol use, but some have found this domain to be associated with alcohol-related problems (Cooper, 1994). These differential relations highlight the importance of examining unique drinking motives—particularly enhancement motives and coping motives—in identifying individuals at high risk for drinking problems.

Previous research supports the possibility that motives mediate the relations between personality traits and substance use behaviors. For instance, in the context of broad personality domains, enhancement motives have been found to mediate the relations between extraversion and alcohol use (Hussong, 2003; Kuntsche, von Fischer, & Gmel, 2008) and between low conscientiousness and increased drinking (Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001). Coping motives, however, have been shown to fully or partially mediate the link between neuroticism and alcohol consumption/problems (Hussong, 2003; Kuntsche, von Fischel, et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2001), highlighting how different motives are distinctly related to personality and patterns of alcohol use. Additionally, research suggests that changes in motives across time impact “maturing out” of problematic alcohol use in young adulthood, with changes in coping motives for drinking being found to mediate the relation between decreases in both neuroticism and impulsivity and decreases in problematic alcohol use (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2010).

The potential mediation of motives in the relation between impulsivity variables and drinking outcomes has also been examined, though not extensively. Some researchers have examined whether motives play a mediating role in the relation between sensation seeking and impulsivity (i.e., lack of premeditation) and alcohol use outcomes. Findings indicated that enhancement motives mediate the link between sensation seeking and alcohol use (Cooper, Frone, Russel, & Mudar, 1995; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005) and combined sensation seeking/impulsivity and problematic alcohol use in a cross-sectional sample (Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003). In a recent study on the relations among impulsivity-related personality, motives, and alcohol use, Magid, MacLean, and Colder (2007) examined whether impulsivity and sensation seeking differed in their relations to alcohol use and problems, and tested whether these relations were uniquely mediated by different drinking motives. Sensation seeking was found to relate significantly to both alcohol use and problems. Most of the effect of sensation seeking on alcohol use was mediated by enhancement motives, and most of the effect sensation seeking had on alcohol problems was mediated by enhancement motives and amount of alcohol used. In contrast, impulsivity had no significant effect on alcohol use but was significantly related to alcohol related problems; however, most of the effect of impulsivity on alcohol problems was mediated by coping motives. The findings of Magid and colleagues emphasize the value of considering motives as a possible mechanism through which an individual's predispositions impact drinking behavior.

Considered together, these studies suggest that examining the mediating role of drinking motives in the relation between impulsivity and alcohol use offers a more complete understanding of the proximal links between personality traits and substance use. While the results of Magid and colleagues (2007) provide an interesting picture of how impulsive personality traits impact behavior, the study was limited in that the focus is only on two traits: sensation seeking and prototypical impulsivity. As described above, recent findings suggest that a thorough examination of the links between impulsive personality and risky drinking should also include urgency. Given that negative urgency operates under conditions of negative emotional arousal, it is possible that individuals engage in risky or impulsive behaviors to cope with their distress. Consistent with previous findings demonstrating that coping motives mediate the relation between neuroticism and drinking habits, it may be that coping motives also mediate the relation between negative urgency—which can be conceptualized as a facet of neuroticism— and drinking problems. Hence, there is both empirical and theoretical support for the inclusion of urgency when examining the mediating role of drinking motives in the relation between personality and problematic drinking.

1.3. The Current Study

The current study considers the potential mediating role of drinking motives in the association between three impulsivity-related personality traits and risky, problematic alcohol use in a sample of college student drinkers. Because the Magid et al. (2007) study examined only prototypical impulsivity and sensation seeking, the present investigation will provide a more complete model by also including negative urgency as a theoretically and empirically relevant predictor of drinking behavior and drinking motives. Examining a fuller range of impulsive personality traits may allow for a better understanding of the proximal link between such traits and substance use. It is hypothesized that three traits—lack of premeditation, sensation seeking, and negative urgency—will relate to problematic alcohol use through unique mediational pathways. Specifically it is hypothesized that: 1) enhancement motives (i.e. drinking to increase positive mood) will mediate the relation between sensation seeking and problematic alcohol use, 2) coping motives will mediate the relation between negative urgency and problematic alcohol use, and 3) lack of premeditation will be directly related to problematic alcohol use and will not be mediated by coping motives when negative urgency is included in the model.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants included 432 undergraduate students (46.9% male; mean age = 19.0 years, sd = 0.8; 84.0% white/Caucasian, 9.7% black/African American, 1.7% Latino, 2.7% Asian, 2.0% other) recruited as part of a longitudinal project examining correlates of substance use and abuse among young adults; only data collected in Wave 1 were used in the present study. Only individuals who endorsed consuming alcohol in year prior to participating were included in the analysis, because drinking motives would not be applicable among abstainers.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Impulsivity

The UPPS-P Impulsive Behaviors Scale (Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2006) is a 59-item inventory designed to measure five personality traits linked to impulsive behavior: Negative Urgency, (lack of) Premeditation, (lack of) Perseverance, Sensation Seeking, and Positive Urgency. Each item on the UPPS-P is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. Average scores were calculated for each scale. All scales demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the present sample (alphas: negative urgency = .89, positive urgency = .93, premeditation = .86, perseverance = .82, sensation seeking = .84).

2.2.2. Drinking motives

The Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994) is a 20-item, self-report questionnaire, designed to assess individuals' reasons for engaging in alcohol use. Four scales comprising five items each may be calculated, with each scale measuring either enhancement, coping, conformity, or social motives. Internal consistency for each scale was adequate in the present sample (alphas: enhancement = .89, coping = .85, conformity = .86, social = .81.)

2.2.3. Problematic drinking

Three indicators of problematic alcohol use were collected in the current study. First, participants reported on the highest amount of alcohol they consumed within the past year. Participants completed a life history calendar (LHC) of their substance use. The LHC is a retrospective method for collecting data on a wide range of life events and behaviors (Caspi, Moffitt, Thornton, & Freedman, 1996). The LHC contextualizes the past in terms of grade in school, place of residence, and peer group to facilitate more accurate recall. The LHC is completed in collaboration with an interviewer. Information is obtained regarding occurrence of substance use, frequency of use, average amount of use, and highest amount of use during one sitting. For the highest amount of alcohol consumed variable, participants selected from nine choices describing the most alcohol they used during one sitting during each period (1 – 5 = response corresponds to number of drinks, 6 = six to ten drinks, 7 = ten to fifteen drinks, 8 = sixteen to twenty drinks, 9 = more than 20 drinks). Participants were asked to report on their alcohol use beginning when they were 13 years old up until the time of the interview. Each year was divided into three segments that correspond roughly to the two semesters of the school year and the summer. Responses were averaged across periods representing the year prior to participation. The strong reliability and validity of the LHC have been documented in previous studies relating data from the LHC to adult personality and psychopathology (e.g., Flory, Lynam, Milich, Leukefeld, & Clayton, 2004; Lynam & Miller, 2004).

The other two indicators were derived from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saundersx, & Monteiro, 2001). The AUDIT consists of 10 questions designed to assess three conceptual domains: recent alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and harmful alcohol use. Two scales were computed for the alcohol dependence items (Items 4–6; impaired control over drinking, increased salience of drinking, morning drinking; alpha = .54) and harmful alcohol use items (Items 7–10; guilt after drinking, blackouts, alcohol-related injuries, others concerned about drinking; alpha = .52) by adding scores for responses on each scale. These two scales, along with highest amount of alcohol consumed in the past year, were included as indicators of problematic drinking.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection involved each participant coming into the lab for one, 2.5-hour session during the first-year of college. Sessions were conducted individually with a trained research assistant. Prior to completing self-report measures, participants were screened for the presence of THC, cocaine, opiates, methamphetamine, and benzodiazepines using Accutest SalivaScreen-5 Test kits (Jant Pharmacal Corporation; Encino, CA). Additionally, a field sobriety test was administered to ensure participants were not intoxicated at the time of the study. No participants were intoxicated based on these screening procedures, thus none were excluded. All questionnaires were administered via computer using the MediaLab software program. The LHC was administered as a computer-assisted structured interview. Participants were debriefed verbally by study personnel and in writing at the end of the study. Participants received course credit for taking part in the study. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University's Institutional Review Board. Further, all study personnel completed training in the ethical, responsible conduct of research with human participants.

2.4. Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test our primary hypotheses. SEM analyses were conducted using Mplus Version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). The personality traits were conceptualized as distal predictors of problematic drinking, whereas drinking motives were treated as more proximal mediators. Both traits and motives were modeled as observed variables. Problematic drinking was modeled as a latent variable using highest amount of alcohol consumed in the past year, AUDIT alcohol dependence, and AUDIT harmful alcohol use scores as indicators. The data met assumptions for skewness and kurtosis. No participants were missing data for any variables included in the model.

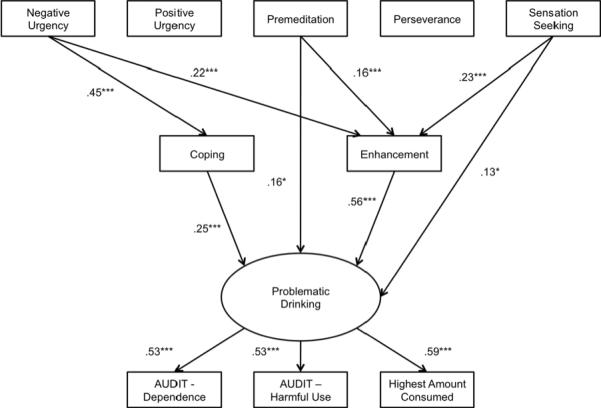

The final structural model was constructed in a stepwise fashion. At the first step, direct paths were specified from each personality trait to the risky drinking outcome variable to determine which traits were related to problematic drinking and therefore candidates for mediation. The second step examined relations between personality traits and drinking motives; thus, paths were specified from the personality traits identified at step 1 to each of the drinking motives1. The third step tested for significant effects of drinking motives on problematic drinking, controlling for personality; the direct paths from personality to problematic drinking identified in step 1 and significant paths linking personality to drinking motives from step 2 were retained, direct paths from drinking motives to problematic drinking were specified, and non-significant paths were removed. The final model, presented as a path diagram in Figure 1, includes all significant paths derived using the process described above. The exogenous personality variables were allowed to correlate. The respective error terms for the drinking motives were also allowed to correlate, as were the error terms for the two indicators of problematic drinking that were drawn from the AUDIT. One thousand bootstrap samples and 99% bias-corrected confidence intervals were used to evaluate the magnitude and statistical significance of the hypothesized direct and indirect effects.

Figure 1.

Results of the structural model. Only significant standardized effects at p < .05 are shown. Proportion of variance accounted for by the model (R2) in the outcome variables: coping motives = .20, enhancement motives = .18, problematic drinking = .67, highest amount of alcohol consumed = .35, AUDIT harmful use = .35, AUDIT dependence = .28. *** p < .001.

Model fit was assessed using four indices: the relative chi-square (CMIN/df), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Guidelines for what constitutes good fit vary across indices. CFI values above either .90 or .95 are thought to represent very good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). RMSEA values of .06 or lower are thought to indicate a close fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999), and SRMR values of approximately .09 or lower are thought to indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

3. Results

3.1. Step 1: Personality to Problematic Drinking

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for all variables considered for inclusion in the model are listed in Table 1. Throughout the results, β is used to represent the estimated standardized direct effect. Consistent with hypotheses, negative urgency (β = .21, p < .05), lack of premeditation (β = .21, p < .01), and sensation seeking (β = .22, p < .001) bore significant, positive relations to problematic drinking. Positive urgency and perseverance were not significantly related to problematic drinking. As such, negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking were identified as candidates for mediation effects in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations, means, and standard deviations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Negative urgency | 1 | 2.27 | .56 | |||||||||

| 2. Positive urgency | .73*** | 1 | 2.06 | .62 | ||||||||

| 3. Lack of premeditation | .41*** | .46*** | 1 | 2.03 | .46 | |||||||

| 4. Lack of perseverance | .33*** | .34*** | .42*** | 1 | 1.86 | .44 | ||||||

| 5. Sensation seeking | .05 | .23*** | .35*** | .04 | 1 | 2.61 | .45 | |||||

| 6. Coping motives | .45*** | .38*** | .21*** | .20*** | .11* | 1 | 2.54 | .98 | ||||

| 7. Enhancement motives | .29*** | .35*** | .34*** | .17*** | .32*** | .46*** | 1 | 3.41 | .91 | |||

| 8. Highest alcohol use, past year | .11* | .17*** | .23*** | .07 | .30*** | .27*** | .48*** | 1 | 4.76 | 2.33 | ||

| 9. AUDIT dependence | .30*** | .31*** | .26*** | .15*** | .18*** | .32*** | .39*** | .34*** | 1 | 1.00 | 1.34 | |

| 10. AUDIT harmful use | .32*** | .30*** | .28*** | .12* | .13** | .37*** | .39*** | .30*** | .61*** | 1 | 2.67 | 2.82 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3.2. Step 2: Personality to Drinking Motives

Paths were specified simultaneously from the three personality traits identified in the first step to coping motives and enhancement motives. As predicted, negative urgency was significantly related to coping motives (β = .45, p < .001). Interestingly, negative urgency was also significantly related to enhancement motives (β = .22, p < .001). Lack of premeditation was significantly related to enhancement motives (β = .16, p < .01), but not coping motives. Sensation seeking was also significantly related to enhancement motives (β = .26, p < .001), but not coping motives. Significant paths were retained for the next step.

3.3. Step 3: Personality, Drinking Motives, and Risky Drinking

In this step, the direct paths from personality to problematic drinking that were found to be significant in Step 1 were reintroduced into the model along with significant paths from personality to motives and from motives to problematic drinking. Results indicated that the direct path from negative urgency to problematic drinking was no longer significant when motives were considered in the model, suggesting a mediating role for coping and enhancement motives in the association between negative urgency and problematic drinking. The direct paths for both lack of premeditation and sensation seeking, however, remained statistically significant. The final model is presented in Figure 1. Overall model fit was good across indices, CMIN = 51.514, df = 24, CMIN/df = 2.146, CFI = .977, RMSEA = .052 (90% CI: .032, .071), SRMR = .049.

Negative urgency bore a significant total effect on problematic drinking through its relations with both coping motives and enhancement motives (estimated standardized total effect = .24, p < .001; see Table 2 for the magnitude of estimated indirect effects and 99% confidence intervals.) Higher levels of negative urgency were associated with stronger endorsement of both coping motives and enhancement motives, which, in turn, were associated with higher problematic drinking scores.

Table 2.

Estimated Standardized Effects of Personality on Problematic Drinking and Their Respective Confidence Intervals

| Estimated standardized effect | 99% CI (Bias-corrected) | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative urgency | ||

| Total effect on problematic drinking | .24***a | .13–.35 |

| Negative urgency→scoping motives→problematic drinking | .11*** | .03 – .19 |

| Negative urgency→Senhancement motives→problematic drinking | .12*** | .05 – .20 |

| Lack of premeditation | ||

| Total effect on problematic drinking | .25** | .05–.44 |

| Lack of premeditation→problematic drinking | .16* | −.05–.28 |

| Lack of premeditation→enhancement motives→problematic drinking | .09** | .02 – .15 |

| Sensation seeking | ||

| Total effect on problematic drinking | .26** | .06–.41 |

| Sensation seeking→Sproblematic drinking | .13* | −.01–.34 |

| Sensation seeking→Senhancement motives→problematic drinking | .13** | .05 – .20 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The discrepancy between the estimated total standardized effect of negative urgency on problematic drinking and the sum of the two estimated indirect effects was due to rounding.

Lack of premeditation bore a significant total effect on problematic drinking (estimated standardized total effect = .25, p < .001). An estimated 36% of the effect of lack of premeditation on problematic drinking was mediated by enhancement motives. Higher levels of lack of premeditation were associated with stronger endorsement of enhancement motives, which was associated with higher problematic drinking scores. The remaining 64% of the estimated total effect was accounted for by the positive, direct effect of lack of premeditation on problematic drinking.

Sensation seeking bore a significant total effect on problematic drinking (standardized total effect = .26, p < .001). Approximately 50% of the total effect of sensation seeking on problematic drinking was mediated by enhancement motives. Higher levels of sensation seeking were associated with stronger endorsement of enhancement motives, which was associated with higher problematic drinking scores. The remaining 50% of the total effect was accounted for by the positive, direct effect of sensation seeking on problematic drinking.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine the mediational role of drinking motives in the relation between impulsive personality traits and risky, problematic alcohol use. Whereas Magid and colleagues (2007) examined only two impulsivity-related traits, the current study included a fuller range of personality traits with well-established associations to impulsive behavior. Most notably, negative urgency, which has been linked empirically to problem drinking and conceptually to coping motives, was considered. Consistent with the conceptualization of the traits acting through distinct pathways to influence behavior, unique patterns of relations were observed between the traits and drinking motives and problematic drinking. Sensation seeking demonstrated a direct effect on problematic drinking and an indirect effect through enhancement motives, with both pathways being roughly equivalent in magnitude. Lack of premeditation, which is conceptually similar to the impulsivity variable used in the study by Magid and colleagues, also bore a direct effect on problematic drinking, consistent with findings from that study. However, a significant indirect effect through enhancement motives, rather than coping motives as in the study by Magid and colleagues (2007), was also observed. Negative urgency was not significantly related to problematic drinking directly, but demonstrated indirect effects through both coping and enhancement motives. It was the only personality trait that was significantly related to coping motives. Although negative urgency exerted only indirect effects on problematic drinking through drinking motives, its total effect was similar to effects observed for sensation seeking and lack of premeditation. The relation of negative urgency to problematic drinking was distinct in that it was the only one of the five impulsive personality traits to relate to coping motives. The other two traits, positive urgency and lack of perseverance, were not significantly related to problematic drinking when the other traits were included in the model.

4.1 Implications of Key Findings

The results of the present study are consistent with previous findings suggesting that motives may operate as a proximal mechanism through which impulsive personality traits impact drinking behavior. Enhancement motives seemed to be particularly influential in the present study, mediating the relations of sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and negative urgency with risky, problematic drinking. This is may be due to the greater relevance of enhancement motives to the average college student drinker than coping motives. From a theoretical standpoint, enhancement motives seem to be quite important to consider in understanding the relation between sensation seeking and problematic drinking, as both represent seeking out pleasurable sensations in spite of potential risk. Consistent with this understanding, and with the findings of Magid and colleagues, the relation between sensation seeking and problematic drinking was partially mediated by enhancement drinking motives, supporting the notion that for individuals who enjoy novel, stimulating experiences, the enhancement of rewarding or pleasurable experience is a particularly salient motivator.

Whereas sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and negative urgency were all related to enhancement motives, negative urgency was the only one of the five impulsive personality traits included here that related to coping motives. Whereas impulsivity (similar to lack of premeditation) related to coping motives in the study by Magid and colleagues, the current study found that it related to enhancement motives. It seems likely that this inconsistency is due to the inclusion of negative urgency in the present study. It may be that urgency can be understood as lack of premeditation that occurs specifically under conditions of emotional arousal. If this is the case, it may be that Magid and colleagues' impulsivity variable included an urgency component, and that this component is responsible for the relation between impulsivity and coping motives. When the lack of premeditation and negative urgency components of impulsivity are parsed out, as they were in the present study, only negative urgency relates to coping motives.

In contrast to the findings of Magid and colleagues, the present study found that lack of premeditation related to enhancement motives for drinking. If the prior study's impulsivity variable included an urgency component, then it makes sense that the relations would look different with the lack of premeditation and urgency components examined separately. Because individuals who are high in lack of premeditation by definition tend to act without considering potential consequences, it follows that they would endorse motives related to the immediate, positive effects of alcohol use.

By examining a more comprehensive set of impulsive personality traits, the present study allowed for a clearer look at the relations between impulsivity and problematic alcohol use. The inclusion of negative urgency seems particularly useful, given that negative urgency follows a unique pathway from other traits in its relation to problematic drinking. This unique pattern of association highlights the importance of considering affect driven impulsive action. It is also worth noting that, despite a high degree of theoretical and statistical overlap, positive urgency did not demonstrate this same pattern of relations, suggesting that it is valuable not only to consider the presence of strong affect, but also the valence of affect.

Although the relation between negative urgency and coping motives makes sense theoretically, there are at least two ways in which these findings may be interpreted. One fairly straightforward interpretation is that individuals who are high in negative urgency use alcohol as a means of coping with distress. Thus, an individual might become distressed and then consume alcohol to dull or eliminate negative affect. Although doing so may be effective at relieving distress in the short term, it may also lead to a variety of negative outcomes associated with intoxication, such as behaving in an embarrassing manner or poor class performance the next day. A second possibility is that individuals high in negative urgency interpret their motivations and behavior incorrectly. That is, these individuals may become upset and act impulsively (i.e. binge drink), and then later perceive this action as an attempt to cope, even if the behavior was not performed with this purpose in mind and did not actually relieve distress. In fact, research suggests that drinking to cope actually has the opposite effect, as coping motives associated with more negative outcomes, as indicated by higher rates of alcohol-related problems (e.g. Kuntsche, Stewart, et al., 2008; Merrill & Read, 2010). Despite the strong possibility that drinking to cope with distress will ultimately lead to more negative outcomes, it may be that for these individuals drinking is still labeled as a way of dealing with distress, with coping motives serving as a “post hoc” explanation for problematic drinking.

4.2 Clinical Implications

As highlighted by the discussion above, the different impulsive personality traits examined demonstrate distinct patterns of relations with drinking motives and problematic alcohol use. These unique pathways suggest that it is useful to consider more specific traits when addressing impulsivity in alcohol use interventions. Indeed, two general pathways emerged: a negative reinforcement pathway and a positive reinforcement pathway.

Negative urgency was the only trait related to coping motives, which in turn related to problematic drinking. This overall pattern could represent a negative reinforcement pathway, through which individuals use alcohol to reduce an unpleasant emotional state. Thus, a goal of treatment for individuals who are high in negative urgency would be to be reduce the use of alcohol consumption as a coping mechanism. Education on the negative social and emotional consequences of using alcohol to cope may be beneficial, as well as training in healthy, adaptive, alternative strategies for coping with negative affect. Because individuals high in negative urgency may not recognize or consider potential negative consequences of alcohol use while they are feeling upset, it would be useful to provide strategies to encourage adequate consideration of possible outcomes.

On the other hand, for individuals who are high in sensation seeking and lack of premeditation, a positive reinforcement pathway to alcohol abuse appears much more relevant, as these individuals endorse drinking to increase positive feelings. While they are focused on the potential positive effects of alcohol, these individuals may not be giving adequate attention or thought to the potential negative consequences of drinking. Thus, one way of intervening may involve working with individuals on considering not only immediate, positive consequences of use, but also on effects that are delayed, which may be less salient in the moment (e.g. hangover, poor grades). Providing alternative behaviors to drinking may also be helpful. Just as individuals who use alcohol to cope may benefit from learning alternative coping strategies, those who drink for enhancement reasons may benefit from learning alternative ways of enhancing positive sensations (e.g. sports). Ideally these behaviors would allow for the experience of excitement, stimulation, and positive mood without the potential negative consequences of risky behavior.

4.3 Limitations and Future Directions

The present study had several limitations that should be addressed in future research. Although the use of the college student sample made sense given the questions of interest, future work should explore these relations in different populations of alcohol users, for example younger teens, high risk adolescents, older adults, and clinical samples of alcohol abusers. Social factors like alcohol availability and norms vary across different populations, and may impact the likelihood that an individual will use alcohol for a given purpose. College represents a unique context in terms of social environment (e.g. heavy drinking is fairly normative), thus it will be important to examine these relations among individuals in different contexts. Level of alcohol use symptomatology may also impact how the relation plays out, for example particular motives may be more common in clinical samples of alcohol abusers than in normal samples of drinkers, so it is important that these relations be examined in individuals with different levels of alcohol use/problems. Another limitation of the sample was that it lacked ethnic and racial diversity, making it impossible to examine whether these relations differ across ethnic or racial groups.

A significant limitation of the current study was the cross-sectional design. Examining these relations in a longitudinal study would allow for a clearer understanding of the relations among personality, drinking motives and drinking outcomes and how these relations change over time. Such longitudinal data are required to establish the temporal ordering of effects. While there is sound theoretical and empirical precedence for the plausible mediation effects observed in the current study, it will be important for future studies to examine how the variables evolve over time to validate this model. Further, although the cross-sectional design limits our ability to test a mediation effect directly, this limitation does not undermine the interesting differential patterns observed for sensation seeking, lack of premeditation, and negative urgency.

The results of the present study suggest that impulsive personality traits and drinking motives play important roles in determining the likelihood of problematic drinking. It may also be useful to examine how these factors impact other aspects of drinking behaviors. The situations in which an individual drinks (e.g. on a Saturday night versus the night before a test) and how they behave while under the influence (e.g. driving a vehicle, risky sex, physical fights) likely impact the level of alcohol-related consequences they experience, but may not be adequately captured by simply examining the amount used. These behaviors would likely be impacted by impulsive personality traits and drinking motives, as individuals may be so focused on a particular outcome state (i.e. reducing negative affect or increasing positive affect) that they disregard less salient factors, such as potential consequences (e.g. doing poorly on a test).

Although lack of perseverance was not significantly related to drinking motives or problematic drinking in the final model, it was significantly related to AUDIT dependence, AUDIT harmful drinking, and both enhancement and coping motives at the zero-order level. These associations may be attributable to those aspects of the construct that are shared with other UPPS-P traits. For instance, lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance may be considered distinct facets a broader trait (i.e., conscientiousness; Smith et al., 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Hence, relations at the zero-order level may reflect the influence of non-specific aspects of lack of perseverance on drinking outcomes. Research addressing this issue has yielded equivocal findings. In studies where lack of premeditation has demonstrated significant relations with alcohol-related problems independent of other impulsivity-related traits, researchers have attributed this link to the diminished sense of obligation and responsibility that is characteristic to lack of perseverance but not necessarily other impulsivity-related traits (Magid & Colder, 2007). Future work is needed to clarify the nature of this association.

Lastly, future research should aim to develop and to examine the effectiveness of treatment approaches tailored to specific impulsive personality traits and drinking motives. The results indicate distinct positive and negative reinforcement pathways, suggesting that targeted approaches may work best for people with particular impulsive personality traits and motives. As discussed above in the clinical implications, these approaches would ideally target the specific reasons individuals give for engaging in alcohol use, and would aim to provide alternative means of achieving the same goal, whether it be increasing feelings of excitement or alleviating negative affect.

Highlights

Drinking motives mediate relations between impulsivity traits and risky drinking.

Premeditation (PRE), sensation seeking (SS) bore direct effects on risky drinking.

PRE and SS bore indirect effects on risky drinking through enhancement motives.

Negative urgency bore indirect effects via coping and enhancement motives.

Risky drinking interventions should be tailored to individuals' personalities.

Acknowledgments

Statement 4: Acknowledgements (optional) The authors wish to thank members of the UK Center for Drug Abuse Research Translation (CDART) for helpful feedback throughout the development of this project.

Role of Funding Sources Funding for this study was provided by NIDA Grant DA005312. NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement 2: Contributors Mr. Adams and Drs. Lynam and Milich designed the study. Mr. Adams and Drs. Lynam and Charnigo conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the statistical analysis and results sections. Mr. Adams and Ms. Kaiser conducted literature reviews and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed feedback and revisions throughout the development of this project and have approved the final manuscript.

Statement 3: Conflict of Interest All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

1Only coping and enhancement motives were included in the current analysis because they have demonstrated the most reliable relations with problematic drinking in previous studies. An alternate model including social and conformity motives was also tested in the current study. Neither social nor conformity motives were significantly related to problematic drinking. Thus, all results reported here include only coping and enhancement motives.

References

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care, Second Edition, WHO Document No.WHO/MSD/MSB/01.6a. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SR, Johnson SC, Jacobs PC. Disinhibited characteristics and binge drinking among university student drinkers. Addict Behav. 2010;35(3):242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.020. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Reasons for drinking alcohol: Relationships with DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses and alcohol consumption in a community sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998;12(3):168–184. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.12.3.168. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Thornton A, Freedman D. The life history calendar: A research and clinical assessment method for collecting retrospective event-history data. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1996;6(2):101–114. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1234-988X(199607)6:2<101::AID-MPR156>3.3.CO;2-E. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russel M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox W, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43(4):839–850. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.008. [Google Scholar]

- Dickman SJ. Functional and dysfunctional impulsivity: Personality and cognitive correlates. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;58(1):95–102. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.1.95. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck MW. Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. Plenum; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Farber PD, Khavari KA, Douglass FM. A factor analytic study of reasons for drinking: Empirical validation of positive and negative reinforcement dimensions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1980;48(6):780–781. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.6.780. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.48.6.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT. Binge eating, problem drinking, and pathological gambling: Linking behavior to shared traits and social learning. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;44(4):789–800. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.008. [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(1):193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. doi:10.1017/S0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath LS, Milich R, Lynam D, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Sensation Seeking and Substance Use: A Cross-Lagged Panel Design. Individ Dif Res. 2004;2(3):175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Further refining the stress-coping model of alcohol involvement. Addict Behav. 2003;28(8):1515–1522. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00072-8. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY US: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Stewart SH, Cooper M. How stable is the motive-alcohol use link? A cross-national validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised among adolescents from Switzerland, Canada, and the United States. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(3):388–396. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, von Fischer M, Gmel G. Personality factors and alcohol use: A mediator analysis of drinking motives. Pers Individ Dif. 2008;45(8):796–800. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.08.009. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119(1):93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. doi:10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Miller JD. Personality pathways to impulsive behavior and their relations to deviance: Results from three samples. J Quant Criminol. 2004;20:319–342. doi: 10.1007/s10940-004-5867-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, Cyders MA. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior (Tech. Rep.) Purdue University; West Lafayette, IN: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS impulsive Behavior scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:1927–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.013. [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addict Behav. 2007;32(10):2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1037/a0020135. doi:10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Flory K, Lynam D, Leukefeld C. A test of the four-factor model of impulsivity-related traits. Pers Individ Dif. 2003;34(8):1403–1418. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00122-8. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Sixth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::AID-JCLP2270510607>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente C, Gutiérrez J, Abellán I, López A. Sensation seeking, attitudes toward drug use, and actual use among adolescents: Testing a model for alcohol and ecstasy use. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(11):1615–1627. doi: 10.1080/10826080802241151. doi:10.1080/10826080802241151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(1):13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Desai RA, Smith AE, Cavallo DA, Liss TB, McFetridge A, Krishnan-Sarin S. Impulsive sensation seeking, parental history of alcohol problems, and current alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents. J Addict Med. 2008;2(4):185–193. doi: 10.1097/adm.0b013e31818d8916. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e31818d8916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders M, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. doi:10.1037/a0017631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(3):326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14:155–171. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Loughlin H, Rhyno E. Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain—drinking relations in young adults. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30(2):271–286. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00044-1. [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Bechara A, Recknor EC, Perez-Garcia M. Negative emotion-driven impulsivity predicts substance dependence problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.025. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30:669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]