Abstract

Introduction

Noonan syndrome (NS) is a disorder of RAS- mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway with clinical features of skeletal dysplasia. This pathway is essential for regulation of cell differentiation and growth including bone homeostasis. Currently, limited information exists regarding bone mineralization in NS.

Material and Methods

Using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), bone mineralization was evaluated in 12 subjects (mean age 8.7 years) with clinical features of NS. All subjects underwent genetic testing which showed mutations in PTPN11 gene (N=9) and SOS1 gene (N=1). In a subgroup of subjects with low bone mass, indices of calcium-phosphate metabolism and bone turnover were obtained.

Results

50% of subjects had low bone mass as measured by DXA. Z-scores for bone mineral content (BMC) were calculated based on age, gender, height, and ethnicity. Mean BMC z-score was marginally decreased at -0.89 {95% CI -2.01 to 0.23; p=0.1}. Mean total body bone mineral density (BMD) z-score was significantly reduced at -1.87 {95% CI -2.73 to -1.0; p= 0.001}. Mean height percentile was close to -2 SD for this cohort, thus total body BMD z-scores were recalculated, adjusting for height age. Adjusted mean total body BMD z-score was less reduced but still significant at -0.82 {95% CI -1.39 to -0.25; p= 0.009}. Biochemical evaluation for bone turnover was unremarkable except serum IGF- I and IGF-BP3 levels which were low-normal for age.

Discussion

Children with Noonan syndrome have a significantly lower total body BMD compared to age, gender, ethnicity and height matched controls. In addition, total BMC appears to trend lower in children with Noonan syndrome compared to controls. We conclude that the metabolic bone disease present resulted from a subtle variation in the interplay of osteoclast and osteoblast activity, without clear abnormalities being defined in the metabolism of either. Clinical significance of this finding needs to be validated by larger longitudinal studies. Also, histomorphometric analysis of bone tissue from NS patients and mouse model of NS may further elucidate the relationship between the RAS- MAP kinase pathway and skeletal homeostasis.

Keywords: Noonan syndrome, Bone mineral density, RAS-MAPK pathway, DXA

1.1 INTRODUCTION

NS (OMIM ID: 163950) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by dysmorphic facies, short stature, delayed puberty, cardiac defects, and chest and spine deformities. About 50% of the NS patients have a missense PTPN11 mutation along with less common mutations in KRAS, SOS1, NRAS, and RAF1 genes. [1-4]. PTPN11 encodes Src homology 2 domain containing tyrosine phosphatase 2 (SHP-2), a protein tyrosine phosphatase that acts in the RAS-mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction pathway. PTPN11 mutations in NS are mostly gain of function, disrupting SHP-2's activation mechanism. Abnormally increased phosphatase activity of mutant SHP-2 has also been implicated in leukemogenesis in patients with NS [5].

Others and we have reported that children as well as adults with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) have low bone mass [6-14]. The NF1 gene encodes neurofibromin, a multidomain molecule involved in regulation of several intracellular processes, including the ERK, RAS-MAP kinase cascade, adenylyl cyclase, and cytoskeletal assembly. Recent studies investigating neurofibromin have suggested several important roles in skeletal development and growth. Nf1 inactivation in murine undifferentiated mesenchymal cells leads to bowing of tibia and diminished growth associated with decreased stability of the cortical bone, higher degree of porosity, decreased stiffness and reduction in the mineral content. At the cellular level, osteoblasts showed an increase in proliferation and a decreased ability to differentiate and mineralize in vitro [15]. In addition to an osteoblastic defect, Nf1+/- mice were found to contain elevated numbers of osteoclasts with increased resorptive activity [16]. Also, osteoclasts from patients with NF1 were reported to be insensitive to bisphosphonates in vitro. Ras inhibitor FTS counteracted the insensitivity of osteoclasts to bisphosphonates [17]. These reports suggest that RAS-MAPK pathway is important in postnatal skeletal homeostasis.

NS is also a disorder of RAS-MAPK pathway. While clinical features such as short stature, chest and spine deformities suggest an underlying skeletal dysplasia; little information is known about mineralization of bone and associated function of osteoblasts and osteoclasts on a tissue level. Stevenson et al studied urine markers of bone resorption in patients with RAS-MAPK pathway disorders (N=49), which included 14 patients with Noonan syndrome. Their data suggested increased bone resorption in these patients compared to control subjects (N=99) [18]. Takagi reported 2 adult male patients with NS with osteopenia and postulated estrogen deficiency as a possible etiology [19]. Noordam et al studied 16 children with Noonan syndrome before and after growth hormone therapy and reported low trabecular vBMD at baseline with improvement following growth hormone therapy [20]. Reinker et al also reported 2 adult patients with NS with osteopenia but no information was provided regarding how the diagnosis was made [21].

In the present study, we investigated the bone mineral status in a group of children with clinical and molecular diagnosis of NS compared to age, gender, and ethnicity matched controls using DXA. Our aim was to determine whether gain of function of RAS-mitogen activated protein kinase signal transduction seen in NS can result in abnormal bone mass due to altered bone formation or resorption. We also assessed bone metabolic markers in patients with low BMD as defined by z-score of < -2.

1.2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The IRB approved the study for Human Subject Research at Baylor College of Medicine. Informed, written consent was obtained from parents. Based on variability between subjects and DXA scan, sample size of 10 for Noonan syndrome cohort was calculated to detect a difference of 10%. This assumes a type I error of 0.05 and power of 0.8.

12 patients were recruited from Pediatric Endocrinology Clinic and/or Medical Genetics Clinic at Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, Texas. All the subjects were diagnosed with Noonan syndrome based on clinical features and underwent genetic testing. These subjects were unselected for skeletal problems. Patients with metabolic bone disorders or on medications known to affect bone metabolism such corticosteroids and growth hormone were excluded. Height (±0.5 cm) was measured with a stadiometer, and weight (±0.1 kg) was measured on a standard clinical balance. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Dietary calcium intake was assessed by detailed food frequency questionnaire about dairy products [22]. Drug intake and fracture history were also included in the medical history.

Bone mineral content and areal bone density measurements were obtained with a Hologic Delphi-A instrument (Software version 11.2). The following bone parameters were obtained: BMC, bone area, and BMD. DXA results are presented as z scores {z=(subject BMD - matched control BMD)/control SD} where controls were matched for age, gender and ethnic background from the database maintained at the Body Composition Laboratory of the Children's Nutrition Research Center for healthy children [23]. We used only total body measurements since on adjusting for height age, most of the children were <8 years old and z-score for lumbar spine measurements were not available for ages <8 years.

Full bone metabolism work up including serum calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, intact parathyroid hormone levels by immunochemiluminometric assay, 25 hydroxy vitamin D (by liquid chromatography, tandem mass spectrometry), osteocalcin by immunoradiometric assay and urinary collagen I N-telopeptide by enhanced chemiluminescence were done at clinic visit after DXA showed BMD z-score of <-2. IGF-1, IGFBP3 levels were measured by immunoassay.

We used SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) for statistical analysis. The distribution of z-scores was normal (using one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and hence comparison of z-score mean with the zero mean reference value was made with the parametric two-sided one-sample t-test. 95th centile confidence intervals were calculated.

1.3 RESULTS

12 children with NS (9 males, 3 females) participated in the study. This cohort included different ethnicities representative of the region and diversity of the Clinics at Texas Children's Hospital: Caucasian (n=6), Hispanic (n=4) and Asian (n=2). Mean age of patients was 8.7 ± 4.2 years (Range: 3.8-15.8 years). Eleven subjects were prepubertal at Tanner stage 1 and one subject was at Tanner stage 3. Eleven of the twelve patients had facial dysmorphism characteristic of Noonan syndrome. These patients also had variable degree of developmental delay. Pulmonary stenosis was the most common congenital heart disease found in 9 out of 12 patients. One patient who had mutation in the SOS-1 gene did not have any cardiac abnormalities. One patient also had Tetralogy of Fallot and another one had pulmonary stenosis as a part of hypoplastic right heart syndrome. Two patients also had coagulopathy and four male subjects had history of cryptorchidism.

Nine patients had mutation in PTPN11 gene and one patient in SOS1. Mutation analysis of PTPN11, KRAS, RAF-1, and SOS-1 was negative in 2 patients (Table 1). The mutation in the PTPN11 gene in patient 3 resulted in amino acid change of Valine to Leucine at codon 354 (p.V354L). This is a novel variant but is not considered to be causative, even though he had several clinical features of NS. Array comparative genomic hybridization analysis showed that this patient and his mother had a gain of one clone on the subtelomeric region of the short arm of chromosome 20 [arr cgh>20p13(RP11-371L19) x3.nuc ish 20p13(RP11-371L19x3)] (chr20: 659,205-785,463). The SIRPA gene is located centromeric to this region (chr20: 1822813-1868540), which encodes a product that acts as docking protein and induces translocation of PTPN6, PTPN11 and other binding partners from the cytosol to the plasma membrane.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the children with NS

| Patient | Gender | Age (yrs) | Height cm (%ile) | Height Age (yrs) | Weight kg (%ile) | Affected gene | Mutation analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 3.8 | 89.2 (0.7) | 2.5 | 12 (1.4) | PTPN11 | c.854 T>C (p.F285S) |

| 2 | M | 9.1 | 120.3 (1.1) | 7 | 21 (0.89) | PTPN11 | c.853 T>C (p.F285L) |

| 3 | M | 4 | 101.8 (44.5) | 4 | 17.6 (73.6) | None | |

| 4 | M | 5.5 | 93.8 (0.01) | 3.5 | 13.5(0.04) | PTPN11 | c.172 A>G (p.N58D) |

| 5 | M | 6.1 | 108.6 (7.1) | 5 | 18.1 (13.4) | SOS1 | c.1264 A>G (p.M422V) |

| 6 | F | 13.2 | 148.8 (8.5) | 11.7 | 47.2 (53) | None | |

| 7 | F | 9.4 | 118.4 (0.3) | 6.5 | 26.4 (20.5) | PTPN11 | c.214 G>T (p.A72S) |

| 8 | M | 15.8 | 152.1 (0.5) | 12.5 | 49 (10.2) | PTPN11 | c.236 A>G (p.Q79R) |

| 9 | M | 12.5 | 130 (0.14) | 8.5 | 28.5 (0.8) | PTPN11 | c.236 A>G (p.Q79R) |

| 10 | M | 5.3 | 99.2 (0.8) | 3.5 | 18.3(37.8) | None | |

| 11 | M | 13.7 | 139.2 (0.3) | 10.2 | 29.3(0.06) | PTPN11 | c.922 A>G (p.N308D) |

| 12 | M | 5.8 | 110.1(21.3) | 5.1 | 17.6 (14) | PTPN11 | c.236 A>G (p.Q79R) |

As expected, the mean height z-score was reduced at -2.14. The mean BMI was 50th %tile ± 30.01. The mean calcium intake was 942.8±254 mg/day. None of the subjects enrolled were taking corticosteroids, growth hormone or any other medication affecting bone metabolism. None of our patients had history of fractures.

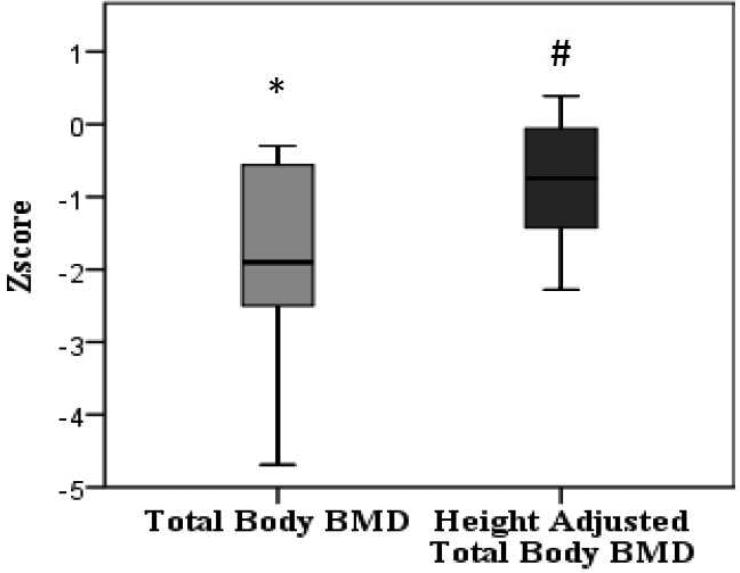

The mean BMC z-score was reduced at -0.88 {95% CI -2.01; 0.23}, p = 0.109. Mean total body BMD z-scores was -1.87 {95% CI -2.73; -1.0}, p = 0.001 (Figure 1). The use of z-score does not consider differences in body size between healthy children and children with NS of the same age. As most of our patients’ heights were below -2 SD for general population, we recalculated total body BMD z-score based on their height age. The recent prediction models for adjusting for stature published by Zemel et al could not be utilized as most of our cohort was of less than 7 years of age. The mean adjusted total body BMD z- score was -0.82 {95% CI -1.39; -0.25}, p= 0.009 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Whole Body BMD z-scores without and with adjustment for short stature. * p <0.01 compared to healthy controls, # p <0.01 compared to healthy controls

In patients with low BMD as defined by z-score <-2 (N=6), we evaluated several markers of bone metabolism (Table 2). All biochemical parameters measured were within the normal range. Serum IGF-1 and IGFBP3 were in the low normal range for the respective age groups.

Table 2.

Biochemical markers of bone metabolism (n=6)

| Biochemical marker (units) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.7 ± 0.49 |

| Magnesium (mg/dl) | 2.05 ± 0.08 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 4.8 ± 0.46 |

| 25 (OH) Vitamin D (ng/ml) | 28 ± 4.51 |

| Intact Parathyroid hormone (pg/ml) | 38.8 ± 25.9 |

| Osteocalcin (ng/ml) | 111 ± 63.5 |

| NTx (nmoles/nmole of creatinine) | 569.6 ± 188.7 |

| IGF-1 (ng/ml) | 187 ± 155 |

| IGF BP3 (mg/L) | 3.52 ± 0.9 |

1.4 DISCUSSION

Bone mass is in part determined by the coupling of bone formation and bone resorption. The cellular drivers of these two processes are osteoblasts and osteoclasts respectively. The exact role of RAS-MAPK pathway in regulation of bone homeostasis is not clear. As mentioned earlier NF1 and NS are both genetic disorders associated with dysregulation of RAS-MAPK pathway. The NF1 gene encodes for neurofibromin that negatively regulates the activity of an intracellular signaling molecule RAS by functioning as a GTPase activating protein (RAS-GAP) [24, 25]. Haploinsufficiency or a complete deficiency in NF1 results in a dose-dependent increase in RAS activity, which in turn can activate a variety of downstream signaling pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. In so doing, mutations can affect proliferation and differentiation in a cell type specific manner. Several research groups have shown that osteoprogenitors and osteoblasts from Nf1+/− mice, and NF1 haploinsufficient human embryonic bone cells showed reduced expression of bone markers and/or produced less mineralized matrix when grown under osteogenic conditions [26-29]. When cultured ex vivo, myeloid precursors from Nf1+/− mice generated more osteoclasts at lower concentrations of MCSF/RANKL than precursors from wild type mice. This study also reported increased myeloid progenitors and osteoclasts in Nf1+/− mice in vivo. These findings correspond with prior studies that show RAS-dependent MAPK activity is essential for normal osteoclast function and survival [27, 30]. Patients with NF1 are known to have low bone mass [6-14]. Also, reduced trabecular bone volume and significantly increased osteoid along with increased osteoblasts and osteoclasts were reported in 14 patients with NF1 [31]. Recently, a small case series reported generalized osteoporosis in two infants with Costello syndrome, another disorder of RAS-MAP kinase pathway [32].

In our study, we report a statistical difference in adjusted total body BMD z-scores and a trend towards significance for BMC z-scores indicating lower bone mineralization in children with NS as compared to age, gender, height and ethnicity matched controls. The bone metabolism markers in our cohort, however, were normal for their age. We conclude that the metabolic bone disease present resulted from a subtle variation in the interplay of osteoclast and osteoblast activity, without clear abnormalities being defined in the metabolism of either. Clinical significance of this finding needs to be validated by longitudinal studies.

Limitations of our study include the small sample size and lack of information regarding family history of bone disease, exercise and vitamin D intake, which would be helpful to gain insight into etiology. Also, we lack information on bone age at the time of DXA as delayed bone age can confound our bone mineral density measurements. In addition, given the young age of our cohort we were unable to assess regional bone density measurements. None of our study subjects had fractures; hence, it is unclear whether low BMC and BMD in this population will lead to higher incidence of fractures in future. A larger longitudinal study is necessary to evaluate the natural history of bone disease in NS. Also, histomorphometric analysis of bone tissue obtained from patients with NS and mouse model of NS may allow us to establish associations between molecular defect in the RAS-MAP kinase pathway and alterations in function of osteoblasts and osteoclasts on a tissue level.

Highlights.

- Limited literature on bone mineralization in Noonan syndrome (NS) is available.

- Children with NS underwent DXA. Results were adjusted for short stature.

- Children with NS have low BMD compared to age and height matched controls.

- Total body BMC appears to trend lower in children with NS compared to controls.

- Bone metabolic markers were normal suggesting intrinsic skeletal defect.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Baylor College of Medicine General Clinical Research Center at Texas Children's Hospital. NIH/NICHD P01 HD 22657 Developmental Studies in Skeletal Dysplasias, Baylor Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center grant number 5P30HD024064-23 and National Institutes of Health, M01-RR00188 (General Clinical Research Center) supported this study.

Abbreviations

- NS

Noonan syndrome

- NF1

Neurofibromatosis type 1

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- BMC

Bone mineral content

- DXA

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Gelb BD, Tartaglia M. Noonan syndrome and related disorders: dysregulated RAS-mitogen activated protein kinase signal transduction. Human molecular genetics. 2006;15:R220–226. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl197. Spec No 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carta C, Pantaleoni F, Bocchinfuso G, Stella L, Vasta I, Sarkozy A, Digilio C, Palleschi A, Pizzuti A, Grammatico P, Zampino G, Dallapiccola B, Gelb BD, Tartaglia M. Germline missense mutations affecting KRAS Isoform B are associated with a severe Noonan syndrome phenotype. American journal of human genetics. 2006;79:129–135. doi: 10.1086/504394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schubbert S, Zenker M, Rowe SL, Boll S, Klein C, Bollag G, van der Burgt I, Musante L, Kalscheuer V, Wehner LE, Nguyen H, West B, Zhang KY, Sistermans E, Rauch A, Niemeyer CM, Shannon K, Kratz CP. Germline KRAS mutations cause Noonan syndrome. Nature genetics. 2006;38:331–336. doi: 10.1038/ng1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zenker M, Horn D, Wieczorek D, Allanson J, Pauli S, van der Burgt I, Doerr HG, Gaspar H, Hofbeck M, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Koch A, Meinecke P, Mundlos S, Nowka A, Rauch A, Reif S, von Schnakenburg C, Seidel H, Wehner LE, Zweier C, Bauhuber S, Matejas V, Kratz CP, Thomas C, Kutsche K. SOS1 is the second most common Noonan gene but plays no major role in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Journal of medical genetics. 2007;44:651–656. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tartaglia M, Martinelli S, Cazzaniga G, Cordeddu V, Iavarone I, Spinelli M, Palmi C, Carta C, Pession A, Arico M, Masera G, Basso G, Sorcini M, Gelb BD, Biondi A. Genetic evidence for lineage-related and differentiation stage-related contribution of somatic PTPN11 mutations to leukemogenesis in childhood acute leukemia. Blood. 2004;104:307–313. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dulai S, Briody J, Schindeler A, North KN, Cowell CT, Little DG. Decreased bone mineral density in neurofibromatosis type 1: results from a pediatric cohort. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2007;27:472–475. doi: 10.1097/01.bpb.0000271310.87997.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lammert M, Kappler M, Mautner VF, Lammert K, Storkel S, Friedman JM, Atkins D. Decreased bone mineral density in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2005;16:1161–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1940-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevenson DA, Moyer-Mileur LJ, Murray M, Slater H, Sheng X, Carey JC, Dube B, Viskochil DH. Bone mineral density in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. The Journal of pediatrics. 2007;150:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunetti-Pierri N, Doty SB, Hicks J, Phan K, Mendoza-Londono R, Blazo M, Tran A, Carter S, Lewis RA, Plon SE, Phillips WA, O'Brian Smith E, Ellis KJ, Lee B. Generalized metabolic bone disease in Neurofibromatosis type I. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2008;94:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duman O, Ozdem S, Turkkahraman D, Olgac ND, Gungor F, Haspolat S. Bone metabolism markers and bone mineral density in children with neurofibromatosis type-1. Brain & development. 2008;30:584–588. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Illes T, Halmai V, de Jonge T, Dubousset J. Decreased bone mineral density in neurofibromatosis-1 patients with spinal deformities. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2001;12:823–827. doi: 10.1007/s001980170032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuorilehto T, Poyhonen M, Bloigu R, Heikkinen J, Vaananen K, Peltonen J. Decreased bone mineral density and content in neurofibromatosis type 1: lowest local values are located in the load-carrying parts of the body. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2005;16:928–936. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1801-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker T, Schnabel C, Hartmann M, Friedrich RE, Frieling I, Kruse HP, Mautner VF, Friedman JM. Bone health and fracture rate in individuals with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) Journal of medical genetics. 2009;46:259–265. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.061895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yilmaz K, Ozmen M, Bora Goksan S, Eskiyurt N. Bone mineral density in children with neurofibromatosis 1. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:1220–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolanczyk M, Kossler N, Kuhnisch J, Lavitas L, Stricker S, Wilkening U, Manjubala I, Fratzl P, Sporle R, Herrmann BG, Parada LF, Kornak U, Mundlos S. Multiple roles for neurofibromin in skeletal development and growth. Human molecular genetics. 2007;16:874–886. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang FC, Chen S, Robling AG, Yu X, Nebesio TD, Yan J, Morgan T, Li X, Yuan J, Hock J, Ingram DA, Clapp DW. Hyperactivation of p21ras and PI3K cooperate to alter murine and human neurofibromatosis type 1-haploinsufficient osteoclast functions. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:2880–2891. doi: 10.1172/JCI29092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heerva E, Peltonen S, Svedstrom E, Aro HT, Vaananen K, Peltonen J. Osteoclasts derived from patients with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) display insensitivity to bisphosphonates in vitro. Bone. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevenson DA, Schwarz EL, Carey JC, Viskochil DH, Hanson H, Bauer S, Weng HY, Greene T, Reinker K, Swensen J, Chan RJ, Yang FC, Senbanjo L, Yang Z, Mao R, Pasquali M. Bone resorption in syndromes of the Ras/MAPK pathway. Clinical genetics. 2011;80:566–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takagi M, Miyashita Y, Koga M, Ebara S, Arita N, Kasayama S. Estrogen deficiency is a potential cause for osteopenia in adult male patients with Noonan's syndrome. Calcified tissue international. 2000;66:200–203. doi: 10.1007/s002230010040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noordam C, Span J, van Rijn RR, Gomes-Jardin E, van Kuijk C, Otten BJ. Bone mineral density and body composition in Noonan's syndrome: effects of growth hormone treatment. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism : JPEM. 2002;15:81–87. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2002.15.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinker KA, Stevenson DA, Tsung A. Orthopaedic conditions in Ras/MAPK related disorders. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2011;31:599–605. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318220396e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angus RM, Sambrook PN, Pocock NA, Eisman JA. A simple method for assessing calcium intake in Caucasian women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1989;89:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellis KJ, Shypailo RJ, Hardin DS, Perez MD, Motil KJ, Wong WW, Abrams SA. Z score prediction model for assessment of bone mineral content in pediatric diseases. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2001;16:1658–1664. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.9.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bollag G, Clapp DW, Shih S, Adler F, Zhang YY, Thompson P, Lange BJ, Freedman MH, McCormick F, Jacks T, Shannon K. Loss of NF1 results in activation of the Ras signaling pathway and leads to aberrant growth in haematopoietic cells. Nature genetics. 1996;12:144–148. doi: 10.1038/ng0296-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormick F. Ras signaling and NF1. Current opinion in genetics & development. 1995;5:51–55. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(95)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein BY, Rojansky N, Gal I, Shlomai Z, Liebergall M, Ben-Bassat H. Analysis of cell-mediated mineralization in culture of bone-derived embryonic cells with neurofibromatosis. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 1995;57:530–542. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240570318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyazaki T, Katagiri H, Kanegae Y, Takayanagi H, Sawada Y, Yamamoto A, Pando MP, Asano T, Verma IM, Oda H, Nakamura K, Tanaka S. Reciprocal role of ERK and NF-kappaB pathways in survival and activation of osteoclasts. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;148:333–342. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X, Estwick SA, Chen S, Yu M, Ming W, Nebesio TD, Li Y, Yuan J, Kapur R, Ingram D, Yoder MC, Yang FC. Neurofibromin plays a critical role in modulating osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells. Human molecular genetics. 2006;15:2837–2845. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu X, Chen S, Potter OL, Murthy SM, Li J, Pulcini JM, Ohashi N, Winata T, Everett ET, Ingram D, Clapp WD, Hock JM. Neurofibromin and its inactivation of Ras are prerequisites for osteoblast functioning. Bone. 2005;36:793–802. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura H, Hirata A, Tsuji T, Yamamoto T. Role of osteoclast extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in cell survival and maintenance of cell polarity. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2003;18:1198–1205. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.7.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seitz S, Schnabel C, Busse B, Schmidt HU, Beil FT, Friedrich RE, Schinke T, Mautner VF, Amling M. High bone turnover and accumulation of osteoid in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2010;21:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0933-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Digilio MC, Sarkozy A, Capolino R, Chiarini Testa MB, Esposito G, de Zorzi A, Cutrera R, Marino B, Dallapiccola B. Costello syndrome: clinical diagnosis in the first year of life. European journal of pediatrics. 2008;167:621–628. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]