Abstract

Introduction

Renal artery dissection is a rare cause of abdominal pain. The renal arteries are the commonest site of primary dissection involving visceral vessels but spontaneous bilateral dissection is extremely rare.

Presentation of case

We present a case of spontaneous bilateral renal artery dissection in a previously fit 43-year-old man who presented with right iliac fossa pain. He was treated conservatively with anticoagulation for 6 months, with resolution of the dissections on imaging at 6-month follow-up.

Discussion

The presentation of spontaneous renal artery dissection is non-specific, making it a diagnostic challenge. Computed Tomography angiography is now the gold standard for diagnosis and follow-up of these patients.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of considering other causes of abdominal pain in a young man with normal initial investigations and the role of conservative management.

Keywords: Spontaneous renal artery dissection, Management, CT angiography

1. Introduction

The renal arteries are the commonest site of primary dissection involving visceral vessels. Spontaneous bilateral dissection is, however, extremely rare.1 This case highlights the importance of considering other causes of abdominal pain in a young man with normal initial investigations and also the possibility of successful conservative management.

2. Presentation of case

A 43-year-old man presented with a 4-day history of dull, constant, right iliac fossa pain, extending to the suprapubic region. He did not have any gastrointestinal or urinary symptoms and felt systemically well. The patient had no co-morbidities except for one episode of renal colic 5 years earlier. He was apyrexial and haemodynamically stable. His abdomen was soft with mild tenderness in the right iliac fossa without peritonism, distension or masses. Bowel sounds were present. Urinalysis was negative.

Blood results showed a raised white cell count (WCC) of 13.5 × 109/l and c-reactive protein of 7.6, rising to 48.6. Urea, electrolytes and haemoglobin were within normal range.

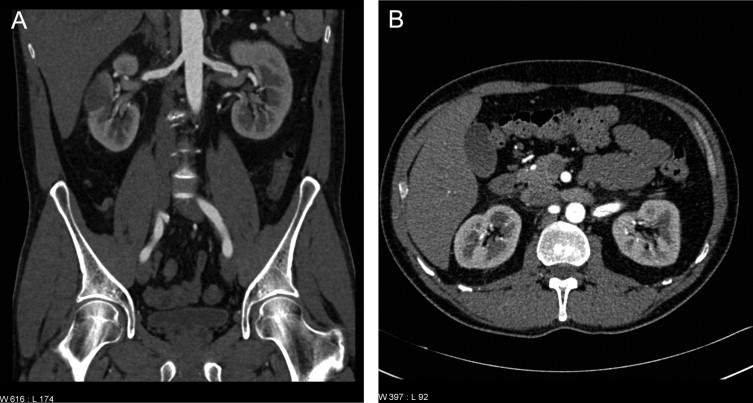

An abdominal ultrasound did not reveal any pathology. The pain was settling however a Computed Tomography (CT) was arranged, revealing several areas of reduced enhancement in the right kidney. CT Angiogram (CTA) showed bilateral renal artery dissections, with 25% established infarction of the right renal parenchyma (Fig. 1a). The right main renal artery was dilated with mural thickening and surrounding inflammatory change. There was a dissection flap in the interpolar branch, containing thrombus, although the artery itself was not completely occluded. On the left, there were two large-diameter renal arteries, with a dissection in the main trunk, 1.5 cm distal to its origin, extending to the main bifurcation, but no compromise of flow (Fig. 1b). There were no dissections involving other visceral arteries, however the superior mesenteric artery and coeliac trunk were of an unusually large diameter.

Fig. 1.

(a) CTA on admission showing the right renal artery dissection flap and renal parenchyma infarction. (b) CTA on admission showing the dissection of the main trunk of the left renal artery.

The patient was discussed in a combined vascular and renal multidisciplinary team meeting and it was thought that, at this stage, thrombolysis would not be beneficial and that percutaneous or surgical intervention to the left renal artery would risk extending the dissection or causing renal infarction. The patient was therefore initially managed conservatively as the renal function had remained stable up to the point of diagnosis and he was normotensive. He was anti-coagulated with intravenous heparin to prevent thrombus extension and pain was controlled with simple analgesia. A repeat CTA 24 h later showed no extension of the dissection so it was agreed with the Nephrologists to continue conservative management. Rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and immunoglobulin levels were within normal limits.

The patient's pain improved within 5 days and he was discharged with the initial plan of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for 6 months followed by a repeat CTA prior to discontinuation of therapy. The repeat CTA showed complete resolution of the dissections. MAG3 and DMSA scans showed only a slight reduction in right kidney function with a perfusion defect. LMWH was discontinued. He was advised to monitor his blood pressure and renal function 3-monthly at his general practitioner and to seek urgent medical advice should he develop any symptoms, as it was impossible to determine whether the condition could recur. The patient remains well and asymptomatic 2 years after the original presentation.

3. Discussion

We present a case of a fit 43-year old man with bilateral spontaneous renal artery dissections resulting in renal infarction, which resolved with conservative management.

The presentation of spontaneous renal artery dissection is non-specific, making it a diagnostic challenge. It usually presents in, otherwise-fit, males in their 30–40 s, with flank pain. Pyrexia, hypertension and haematuria may be present. Differential diagnoses include renal colic, pyelonephritis, thromboembolism with renal infarction, renal vein thrombosis and renal abscess.2

The aetiology includes trauma (blunt injury or iatrogenic damage during angioplasty), underlying arteriopathy, including atherosclerosis and fibromuscular dysplasia, and idiopathic. Recently, a possible association with anti-phospholipid antibody has been reported.3

Blood tests often show a raised white cell count and renal function may deteriorate acutely with an elevated lactate dehydrogenase. Urinalysis sometimes reveals microscopic haematuria. Although CT without contrast will rule out more common causes of the presentation, a contrast-enhanced CT will show areas of renal infarction. Ultrasonography is far less sensitive. CT angiography is the gold-standard investigation as it is non-invasive and can precisely indicate the extent and nature of the vascular disease. Other visceral arteries are also imaged to look for further dissections2 or abnormal vessels. Multi-vessel spontaneous dissections are thought to suggest the presence of underlying arterial disease despite absence of any angiographic or laboratory findings.4

Management options vary widely and comparative studies with long-term follow-up are lacking. Options include: observation; medical management with anticoagulation and control of hypertension2; endovascular intervention with angioplasty and stenting.5 Surgical revascularisation has also been attempted.4 Patients require follow-up to monitor for hypertension, renal infarction, deterioration of renal function, arterial rupture and resolution of dissection.2 Primary nephrectomy should probably only be considered in cases of severe renovascular hypertension. Overall, with the ongoing advances, angioplasty is likely favourable to surgical revascularisation as it is less invasive, less expensive and associated with a lower morbidity.

In this case, as the patient was normotensive, with no renal dysfunction, endovascular stenting was not deemed appropriate. Indeed, several case reports have reported successful conservative management. Parallels can be drawn from the treatment of dissection in the presence of fibromuscular dysplasia: treatment consists of antiplatelet therapy for asymptomatic individuals and percutaneous balloon angioplasty for patients with indications for intervention – hypertension that is not controlled with anti-hypertensives and loss of renal volume because of ischaemic nephropathy.6

There are no reports in the literature looking at the long-term follow-up of patients with spontaneous renal artery dissection, and the possibility of further dissection in the future. It is known that in cases of cervical artery dissection, the recurrence rate is from 0.9 to 4%.7,8

4. Conclusion

We have presented a case of spontaneous bilateral renal artery dissection. The case highlights the importance of considering alternative diagnoses in patients presenting with loin or generalised abdominal pain, who may have only slightly abnormal blood results and for whom other common pathologies have been excluded. CT angiography, rather than conventional angiography, is now the gold standard for diagnosis.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

A.C. Katz-Summercorn: Clinical care of patient and author of manuscript. C.M. Borg: Clinical care of patient and revision of manuscript. P.L. Harris: Clinical care of patient, revision of manuscript and final approval for submission.

Contributor Information

A.C. Katz-Summercorn, Email: katzsummercorn@doctors.org.uk.

C.M. Borg, Email: Cynthia.borg@gmail.com.

P.L. Harris, Email: Peter.harris@uclh.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Mori H., Hayashi K., Tasaki T., Hori T., Yamasaki T., Amamoto Y. Spontaneous resolution of bilateral renal artery dissection: a case report. J Urol. 1986;135:114–116. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45536-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stawicki S.P., Rosenfeld J.C., Weger N., Fields E.L., Balshi J.D. Spontaneous renal artery dissection: three cases and clinical algorithms. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:710–718. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John S.G., John S.G., Pillai U., Vaidyan P.B., Ishiyama T. Spontaneous renal artery dissection. Mo Med. 2010;107:124–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mokri B., Houser O.W.M.D., Stanson A.W. Multivessel cervicocephalic and visceral arterial dissections: Pathogenic role of primary arterial disease in cervicocephalic arterial dissections. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1991;1:117–123. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(10)80002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeon Y.S., Cho S.G., Hong K.C. Renal infarction caused by spontaneous renal artery dissection: treatment with catheter-directed thrombolysis and stenting. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:333–336. doi: 10.1007/s00270-008-9465-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slovut D.P., Olin J.W. Fibromuscular dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1862–1871. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bassetti C., Carruzzo A., Sturzenegger M., Tuncdogan E. Recurrence of cervical artery dissection: a prospective study of 81 patients. Stroke. 1996;27:1804–1807. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Touzé E., Gauvrit J.Y., Moulin T., Meder J.F., Bracard S., Mas J.L. Risk of stroke and recurrent dissection after a cervical artery dissection: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2003;61:1347–1351. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000094325.95097.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]