Abstract

The exocyst is a multi-protein complex essential for exocytosis and plasma membrane remodeling. The assembly of the exocyst complex mediates the tethering of post-Golgi secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane prior to fusion. Elucidating the mechanisms regulating exocyst assembly is important for the understanding of exocytosis. Here we show that the exocyst component Exo70 is a direct substrate of the Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2). ERK1/2 phosphorylation enhances the binding of Exo70 to other exocyst components and promotes the assembly the exocyst complex in response to epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling. We further demonstrate that ERK1/2 regulates exocytosis as blocking ERK1/2 signaling by a chemical inhibitor or the expression of an Exo70 mutant defective in ERK1/2 phosphorylation inhibited exocytosis. In tumor cells, blocking Exo70 phosphorylation inhibits matrix metalloproteinase secretion and invadopodia formation. ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 may thus coordinate exocytosis with other cellular events in response to growth factor signaling.

Keywords: ERK1/2, exocyst, Exo70, vesicle tethering, exocytosis, EGF, invadopodia

INTRODUCTION

Cells respond to extracellular stimuli such as growth factors and hormones by intracellular signal transduction pathways, many of which culminate in the dynamic remodeling of the cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane (Berzat and Hall; Jaffe and Hall, 2005; Pullikuth and Catling, 2007). Membrane trafficking is fundamental to morphogenesis, cell migration, tissue organization and organ development. Proteins that mediate membrane trafficking are thus important targets of regulation by various signaling events (Lecuit and Pilot, 2003; Mellman and Nelson, 2008; Orlando and Guo, 2009). ERK1/2 (Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase 1 and 2) are pivotal components of the classical Ras-MEK-ERK cascade that is activated in response to a variety of stimuli, including epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Chang and Karin, 2001). ERK1/2 are involved in the regulation of many cellular processes including cell proliferation, survival, morphogenesis and migration (Kolch, 2005). Recent studies highlight the role of ERK1/2 in membrane trafficking (Farhan and Rabouille, 2011). For example, in an RNAi screen, Farhan and colleagues found that ERK1/2 phosphorylates Sec16, and this phosphorylation event modulates the number of ER exit sites and ER-to-Golgi transport (Farhan et al., 2010). At the Golgi stage, GRASP55 and GRASP65 are substrates of ERK1/2 (Jesch et al., 2001; Yoshimura et al., 2005); ERK1/2 phosphorylation regulates Golgi cisternal stacking and Golgi polarization in response to growth factors (Bisel et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2003). At the sorting endosomes, ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Rab11-FIP5 controls transcytosis of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in epithelial cells (Su et al., 2010).

The Ras-MEK-ERK pathway has been implicated in the regulation of morphogenesis and cell migration, which are characterized by dynamic plasma membrane remodeling (Klemke et al., 1997; Rajalingam and Rudel, 2005). Exocytosis is important for cell morphogenesis and migration. However, whether the Ras-MEK-ERK pathway regulates exocytosis is unknown. A previous study using live-cell imaging suggests that EGF signaling stimulates vesicle fusion at the plasma membrane (Kawase et al., 2006). It will be interesting to know whether ERK1/2 is involved in regulating exocytosis in response to EGF.

The late stage of exocytosis includes tethering, docking and fusion of post-Golgi secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane (He and Guo, 2009). The tethering step, defined as the initial contact of secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane before SNARE-mediated fusion, is mediated by the exocyst. The exocyst is an evolutionarily conserved octameric protein complex consisting of Sec3, Sec5, Sec6, Sec8, Sec10, Sec15, Exo70, and Exo84 (Guo et al., 2000; Hsu et al., 2004; Munson and Novick, 2006; Wang and Hsu, 2006). It has been postulated that different components of the exocyst are localized at the secretory vesicles and the plasma membrane, respectively. The assembly of the exocyst complex mediates the tethering of secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane.

In this study, we demonstrate that ERK1/2 regulates post-Golgi exocytosis. Furthermore, we identified the exocyst component Exo70 as a direct substrate of ERK1/2. The phosphorylation of Exo70 by ERK1/2 promotes the assembly of the exocyst complex and may thus regulate vesicle tethering at the plasma membrane. In tumor cells, blocking Exo70 phosphorylation inhibits matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) secretion and cell invasion. ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 may coordinate exocytosis with other cellular processes in response to growth factor signaling.

RESULTS

ERK1/2 phosphorylates Exo70 at Serine 250 in response to EGF

In an effort to identify mechanisms of regulation of the exocyst, we have carried out a mass-spectrometry and database search to identify potential phosphorylation of the exocyst subunits in mammalian cells. It was found that an Exo70 phospho-peptide “SSSSSGVPYS*PAIPNK” (S* indicates the phosphorylated serine residue) contains the “PYSP” sequence (Figure 1A) that matches the consensus ERK1/2 phosphorylation motif (“P-x-S/T-P”, where “x” indicates any amino acid) (Beausoleil et al., 2006). We tested whether Exo70 could indeed be phosphorylated by ERK1/2 in cells. HEK293 cells were treated with EGF for 5 min, the endogenous Exo70 in cells was immuno-isolated by an anti-Exo70 monoclonal antibody, and immuno-blotted with the anti-Exo70 antibody and an anti-ERK1/2 phospho-substrate antibody. As shown in Figure 1B, a 3.5-fold increase of ERK1/2 phosphorylated Exo70 was detected in cells treated with EGF (see Supplemental Figure 1 for all the statistical analyses of the binding results shown in Figure 1). As a positive control, ERK1/2 were also phosphorylated in cells in response to EGF as detected by western blotting of the lysates using the anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody.

Figure 1. ERK1/2 phosphorylate Exo70 at Serine 250 in response to EGF.

(A) Exo70 contains a conserved ERK1/2 phosphorylation motif “PYSP” (underlined). The asterisk indicates the potential phosphorylation site of rat Exo70 at Serine 250 (“S250”). (B) Phosphorylation of endogenous Exo70. Exo70 was immunoprecipitated from EGF treated HEK293 cells and then immunoblotted with the anti-Exo70 antibody or anti-ERK1/2 substrate antibody that specifically recognizes the phosphorylation motif in ERK1/2 phosphorylated proteins. The cell lysates were also probed for ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 (“p-ERK1/2”) with antibodies against ERK1/2 and phopsph-ERK1/2, respectively (lower panel). (C) ERK1/2 phosphorylate Exo70 at Serine 250. HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged wild type Exo70, the Exo70(S250A) mutant, and the Flag vector control (“Flag”). Flag-tagged Exo70 proteins were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates using the anti-Flag antibody. The immunoprecipitated Exo70 were analyzed with the anti-ERK1/2 phospho-substrate antibody or the anti-Flag antibody. The anti-ERK1/2 phospho-substrate antibody recognizes the wild type Exo70, but not the Exo70(S250A) mutant (upper panel). The lower panel shows the total amounts of immunoprecipitated Flag-Exo70 and Flag-Exo70(S250A). (D) EGF stimulated the phosphorylation of Exo70. Cells transfected with Flag-tagged Exo70 were stimulated with EGF for 5 or 10 min. Exo70 was immunoprecipitated and analyzed as described above. (E) Cells were incubated with ERK inhibitor U0126 for 30 min prior to EGF treatment (5 min). Exo70-Flag proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates followed by western blotting as above. U0126 blocked EGF-induced phosphorylation of Exo70 (upper panel). U0126 also blocked ERK1/2 phosphorylation as demonstrated by western blot analysis of the amounts of ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 in the cell lysates (lower panel), indicating the effectiveness of the drug treatment. (F) U0126 inhibits phosphorylation of Exo70 in a dose-dependent manner. Exo70-Flag transfected HEK293 cells were pre-incubated with the indicated amounts of U0126 for 30 min and subsequently stimulated with EGF. Phosphorylation of Exo70 and ERK1/2 was analyzed as above. (G) ERK2 phosphorylates Exo70 in vitro. Purified full-length Exo70 and Exo70 fragment containing amino acids 191–651 (“Exo70-C”) were incubated with constitutively activated recombinant ERK2 and [32P] γ-ATP in an in vitro kinase assay. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The phosphorylation signal was detected in Exo70 and Exo70-C, but not GST. (H) ERK2 phosphorylates Exo70 at Serine 250 in vitro. Recombinant wild type Exo70 or S250A mutant was incubated with constitutively-activated ERK2 (“ERK2-CA”) or kinase-dead mutant ERK2 (“ERK2-KD”). Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The upper panel shows the phosphorylation of Exo70 and ERK2. The lower panel is Coomassie Blue-stained gel showing the amounts of the purified wild type and S250A mutant Exo70 together with the recombinant ERK2 used in the kinase assay. See also Figure S1.

To test whether the serine residue at position 250 (“Serine 250”) is involved in ERK1/2 phosphorylation, HEK293 cells were transfected with expression plasmids containing Flag-tagged wild type Exo70 or Exo70(S250A) mutant, in which Serine 250 was mutated to alanine. An anti-Flag antibody was used to immunoprecipitate Exo70 from the cell lysates. The immunoprecipitated proteins were blotted with an antibody that specifically recognizes the ERK1/2 phosphorylation motif. The anti-ERK1/2 phospho-substrate antibody recognized the wild type Exo70 but not the Exo70(S250A) mutant (Figure 1C), suggesting that Exo70 is phosphorylated by ERK1/2 at Serine 250. Our data indicate that Serine 250 is critical for ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

ERK1/2 are phosphorylated and activated in response to EGF signaling (Chang and Karin, 2001). We therefore tested the level of Exo70 phosphorylation after different periods of EGF stimulation. As shown in Figure 1D, there was a 5-fold increase of Exo70 phosphorylation after 5 min of EGF stimulation. After 10 min, the level of phosphorylation was 2-fold above the basal level. As a control, the total amount of Exo70 remained constant. The pattern of Exo70 phosphorylation corresponded well with that of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the same cells (Figure 1D, lower panels). The decrease of phosphorylation after 10 min of EGF treatment is consistent with the previous observation that ERK1/2 activity oscillates due to EGF receptor down-regulation by endocytosis (Cohen-Saidon et al., 2009). In cells, ERK1/2 is activated by its immediate upstream kinase, MEK1 (Chang and Karin, 2001). In fact, ERK1 and ERK2 are the only known substrates of MEK1 (Kohno and Pouyssegur, 2006). As such, U0126, a specific inhibitor of MEK1, has been commonly used to block the Ras-MEK-ERK pathway, especially ERK1/2 activation. We found that U0126 pre-treatment attenuated EGF-induced phosphorylation of Exo70 (Figure 1E), and the effect is dose-dependent (Figure 1F). Collectively, these data indicate that the ERK1/2 pathway is essential for Exo70 phosphorylation in response to EGF stimulation.

Exo70 is a direct substrate of ERK2

We tested whether Exo70 is a direct substrate of ERK1/2 by an in vitro kinase assay. ERK2 was co-expressed with MEK1 in a single plasmid in bacteria. Since MEK1 phosphorylates and thus activates ERK2, the purified recombinant ERK2 is constitutively activated (“ERK2-CA”) (Khokhlatchev et al., 1997). Recombinant Exo70 full-length or a C-terminal fragment (a.a.191–653) containing Serine 250 (“Exo70-C”) was also purified from bacteria and incubated with ERK2-CA in the presence of [32P] γ-ATP. As shown in Figure 1G, the recombinant Exo70 proteins were phosphorylated by ERK2-CA. As a control, GST was not phosphorylated. To determine whether ERK2 phosphorylates Exo70 at Serine 250, we performed the in vitro kinase assay with the Exo70(S250A) mutant. As shown in Figure 1H, while ERK2-CA was able to phosphorylate Exo70, it failed to phosphorylate the Exo70(S250A) mutant, suggesting that Serine 250 is the site of ERK2 phosphorylation. As a negative control, a ERK2 kinase-dead mutant (“ERK2-KD”) that is deficient in ATP-binding (Khokhlatchev et al., 1997) failed to phosphorylate Exo70 or Exo70(S250A). Collectively, these results demonstrate that Exo70 is a direct substrate of ERK2 and Serine 250 is a key site for ERK2 phosphorylation. We were not able to examine the phosphorylation of Exo70 by ERK1 due to the lack of reagents. But it is likely that ERK1 also phosphorylates Exo70 due to its high degree of homology to, and functional overlapping with ERK2 (Kolch, 2005).

ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 promotes VSV-G incorporation to the plasma membrane

We have previously shown that Exo70 mediates the exocytosis of post-Golgi secretory vesicles at the plasma membrane (Liu et al., 2007). RNAi knockdown of Exo70 does not significantly affect the transport of vesicles from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi or from the Golgi to the cell periphery. However, the fusion of the secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane is blocked (Inoue et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2007). Here, using the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) trafficking assay, we have investigated whether ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 affects exocytosis. The VSV-G ts045 mutant is misfolded and restricted in the ER at 40°C. When the temperature is shifted to 20°C, the VSV-G ts045 proteins are properly folded and transported from the ER to the trans-Golgi network (TGN). At this temperature, the VSV-G ts045 protein will be retained at the TGN. The proteins will exit TGN and be transported to the plasma membrane once the temperature is raised to 32°C. We arrested GFP-VSV-G ts045 in the TGN by growing the transfected HeLa cells at 40°C overnight and subsequent shifting to 20°C for 2 hours. We then examined the role of ERK1/2 in Golgi-to-cell surface trafficking by pre-treating the cells with U0126 for 30 min before releasing the VSV-G ts045 protein trafficking at 32°C. To examine the final fusion of the vesicles with the plasma membrane, immunostaining was performed on un-permeabilized cells using the 8G5 monoclonal antibody, which specifically recognizes the extracellular domain of VSV-G (Lefrancois and Lyles, 1982). The amount of VSV-G protein on the cell surface was quantified and normalized to the amount of total VSV-G proteins in cells. As shown in Figure 2A and 2B, after cells were released to 32°C for 30 min, the amount of ts045-VSV-G incorporated to the plasma membrane was reduced by approximately 5-fold in cells treated with U0126. After 60 min of temperature shift, cell surface VSV-G incorporation was about 2-fold lower in the U0126-treated cells. This result suggests that VSV-G exocytosis is delayed in cells, in which the ERK signaling pathway is blocked.

Figure 2. Phosphorylation of Exo70 by ERK1/2 promotes VSV-G exocytosis.

(A) ERK1/2 promotes post-Golgi VSV-G exocytosis. HeLa cells were transfected with ts045-VSV-G-GFP and maintained at 40°C for 16 hours. The temperature was shifted to 20°C for 2 hrs to allow the exit of ts045-VSV-G-GFP from the ER but arrested at the TGN. The cells, with or without U0126 pre-treatment for 30 min, were then shifted to 32°C for 30 or 60 min for ts045-VSV-G vesicles to exit Golgi and transport to the plasma membrane. The cells were processed for immunofluorescence staining with a monoclonal antibody (8G5) against the extracellular domain of VSV-G. The distribution of total (green) and plasma membrane-incorporated ts045-VSV-G-GFP (red, stained by 8G5) were observed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar represents 5 μm. (B) Quantification of VSV-G surface incorporation. Fluorescence signals of the cells were quantified by ImageJ software. VSV-G cell surface incorporation is presented as the ratio of cell surface antibody staining fluorescence to total VSV-G-GFP fluorescence of the cell. Three independent experiments were performed. At least 50 cells were quantified for each group in each experiment. The data were statistically analyzed by student’s t-test. **, P<0.05; ***, P<0.005. “A.U.”, arbitrary units. (C) Western blot showing the levels of knockdown of endogenous Exo70 and the expression of Flag-tagged rat Exo70 variants detected by the anti-Exo70 antibody and anti-Flag antibody. The endogenous Exo70 and Flag-tagged Exo70 are indicated on the blot as they have similar molecular weights. Actin was used as loading control. (D) Exo70 phosphorylation at Serine 250 is important for VSV-G exocytosis. HeLa cells were treated with Exo70 siRNA, and then co-transfected with ts045-VSV-G-GFP with Flag-tagged rat Exo70, Flag-Exo70(S250A), or Flag-Exo70(S250D). VSV-G transport was then examined in cells expressing these Flag-tagged Exo70 variants. VSV-G incorporation to the plasma membrane was reduced in cells expressing Exo70(S250A), but increased in cells expressing Exo70(S250D). Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Quantification of VSV-G surface incorporation in cells expressing wild type, S250A, and S250D mutant Exo70. VSV-G cell surface incorporation was quantified as described above. Comparing to cells expressing wild type Exo70, cell surface incorporation of VSV-G was reduced in cells expressing Exo70(S250A), but increased in cells expressing Exo70(S250D) at both 30 min and 60 min after VSV-G release from the TGN. n=50; *, P<0.05. “A.U.”, arbitrary units. See also Figure S2.

To specifically examine whether ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 affects exocytosis, we used HeLa cells expressing rat Exo70, Exo70(S250A), or Exo70(S250D). The endogenous Exo70 in these cells were knocked down by approximately 85% (Figure 2C), and then VSV-G transport in these cells was examined. As shown in Figure 2D and 2E, cell surface incorporation of VSV-G was lower in cell expressing the Exo70(S250A) mutant than those expressing wild-type Exo70 at both 30 min and 60 min. On the other hand, cells expressing the Exo70(S250D) mutant had higher surface incorporation of VSV-G. Taken together, our data suggest that phosphorylation of Exo70 by ERK1/2 stimulates exocytosis.

Exo70 phosphorylation promotes its interaction with other exocyst components and the assembly of the exocyst complex

How does ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 affect exocytosis? As exocyst complex assembly mediates the tethering of post-Golgi secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane, we examined whether Exo70 phosphorylation by ERK1/2 regulates the interaction of Exo70 with the other exocyst components. HEK293 cells were transfected with Flag-tagged Exo70 or Exo70(S250A). The cells were serum-starved and then treated with EGF or U0126. Exo70 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates with the anti-Flag antibody. The proteins were analyzed by western blot using antibodies against two other exocyst components, Exo84 and Sec8, which were previously shown to interact directly with Exo70 in the exocyst complex (Dong et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 3A–C, EGF stimulated the binding of Exo70 to Sec8 and Exo84. Pre-treating the cells with U0126 abrogated the stimulatory effect of EGF. The binding of the Exo70(S250A) mutant to Sec8 and Exo84 was not enhanced by EGF treatment. Control blots demonstrated that the levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 in cells increased upon EGF stimulation and diminished with U0126 pre-incubation (Figure 3A, lower panel), indicating the effectiveness of EGF and U0126 treatment. To further confirm the effect on binding, we performed the reciprocal immunoprecipitation experiments. Cells expressing Flag-tagged Sec8 were transfected with either Myc-tagged Exo70 or Exo70(S250A). Sec8-Flag was immunoprecipitated using the anti-Flag antibody and the immunoprecipitates were examined for Myc-Exo70 and Exo84 by western blotting. As shown in Figure 3D–F, the amounts of Exo70 and Exo84 that co-immunoprecipitated with Sec8 increased in the EGF treated cells, and U0126 attenuated the stimulatory effect. The binding of the Exo70(S250A) mutant with Sec8 or Exo84 was not increased upon EGF treatment. To examine the interaction of Exo70 with Sec8 at their endogenous levels, HeLa cells were treated with EGF or U0126 as described above. Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using a monoclonal antibody against the endogenous Exo70. The amount of Sec8 that co-immunoprecipitated with Exo70 increased upon EGF stimulation, and U0126 blocked this stimulatory effect (Figure 3G and H).

Figure 3. Exo70 phosphorylation promotes its interactions with other exocyst components in cells.

(A) HEK293 cells expressing Flag-tagged Exo70 or mutant Exo70(S250A) were serum-starved and then treated with EGF or U0126 as indicated. Exo70-Flag was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with the anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by western blotting with antibodies against Exo84 and Sec8 (upper panel). The cell lysates (5% of the inputs) were also analyzed for Exo70-Flag, Sec8, Exo84, ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 (“p-ERK1/2”). (B and C) Quantification of the relative binding of Sec8 and Exo84 with Flag-tagged Exo70 and Exo70(S250A) in the presence of EGF and U0126. The levels of binding were normalized to the basal level (“-EGF/-U0126”). “*”, P<0.05 comparing to the basal level; n=3. “A.U.”, arbitrary units. (D) HEK293 cells co-expressing Flag-tagged Sec8 and Myc-Exo70 or Myc-Exo70(S250A) were treated with EGF or U0126 as described above and used for immunoprecipitation with the anti-Flag antibody. The amounts of Exo70 and Exo84 co-immunoprecipitated with Flag-Sec8 were detected by western blotting. The amount of Exo84 and Myc-Exo70 that co-immunoprecipitated with Sec8 increased with EGF stimulation, and U0126 blocked the stimulatory effect. The cell lysates (5% of the inputs) were also analyzed for Exo70-Myc, Sec8-Flag, Exo84, ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 (“p-ERK1/2”). (E and F) Quantification of the binding of Sec8 and Exo84 with Flag-tagged Exo70 and Exo70(S250A) in the presence of EGF and U0126 as shown in D. (G) HeLa cells were treated with EGF and U0126 as described above. Immunoprecipitation was performed using a monoclonal antibody against the endogenous Exo70. The amount of Sec8 that co-immunoprecipitated with Exo70 increased with EGF stimulation. U0126 blocked the stimulatory effect. (H) Quantification of the binding of Sec8 with the endogenous Exo70 in the presence of EGF and U0126 as shown in G. See also Figure S3.

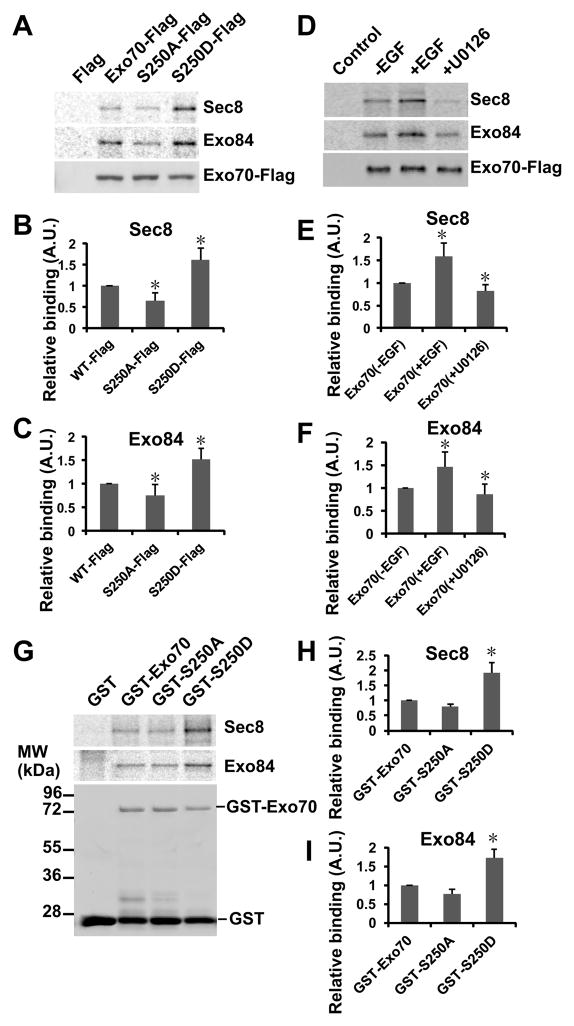

Next, we tested whether phosphorylation of Exo70 affects its interaction with other exocyst complex components in vitro. We purified Flag-tagged wild type Exo70, Exo70(S250A), and Exo70(S250D) from EGF-treated HEK293 cells and incubated them with in vitro translated Sec8 or Exo84 that were radio-labeled with [35S] methionine. As shown in Figure 4A–C, the Exo70(S250D) mutant exhibited stronger interactions with Sec8 and Exo84 than the wild type Exo70 or the Exo70(S250A) mutant. The binding assay was also performed using Flag-tagged Exo70 immuno-isolated from cells stimulated with EGF or pretreated with U0126. Sec8 and Exo84 bound stronger to Exo70-Flag isolated from EGF-treated cells (Figure 4D–F). Finally, using GST-tagged Exo70 variants purified from bacteria, we found that the GST-Exo70-S250D had stronger interactions with Sec8 and Exo84 (Figure 4G–I). Taken together, these data indicate that Exo70 phosphorylation enhances its binding to other exocyst components.

Figure 4. Exo70 phosphorylation enhances its binding to Sec8 and Exo84 in vitro.

(A) Flag-tagged Exo70 and Exo70(S250A) were immuno-purified from the EGF-treated HEK293 cells. Sec8 and Exo84 were in vitro translated in the presence of [35S]-methionine, and used for binding to the Exo70 variants. Wild type Exo70 and Exo70(S250D) had stronger interactions with Sec8 and Exo84 than Exo70(S250A). As a control, anti-Flag immunoglobulin beads incubated with lysates of the untransfected cells did not bind to Sec8 or Exo84. (B–C) Quantification of the binding of Sec8 and Exo84 with Flag-tagged Exo70 in the presence of EGF or U0126 as shown in A. The levels of binding were normalized to the basal level. “*”, P<0.05 comparing to the basal level; n=3. (D) Flag-tagged Exo70 purified from cells treated with EGF has stronger interaction with in vitro translated Sec8 and Exo84 than those purified from untreated cells or cells pre-incubated with U0126. As a control, anti-Flag immunoglobulin beads incubated with lysates of the untransfected cells did not bind to Sec8 or Exo84. (E–F) Quantification of the binding of in vitro translated Sec8 and Exo84 shown in D. (G) GST-tagged wild type and mutant Exo70 were incubated with in vitro translated Sec8 and Exo84. The phospho-mimic Exo70(S250D) mutant has a stronger binding to Sec8 and Exo84. (H–I) Quantification of the binding of in vitro translated Sec8 and Exo84 with recombinant GST-tagged Exo70, Exo70(S250A), and Exo70(S250D) as shown in G.

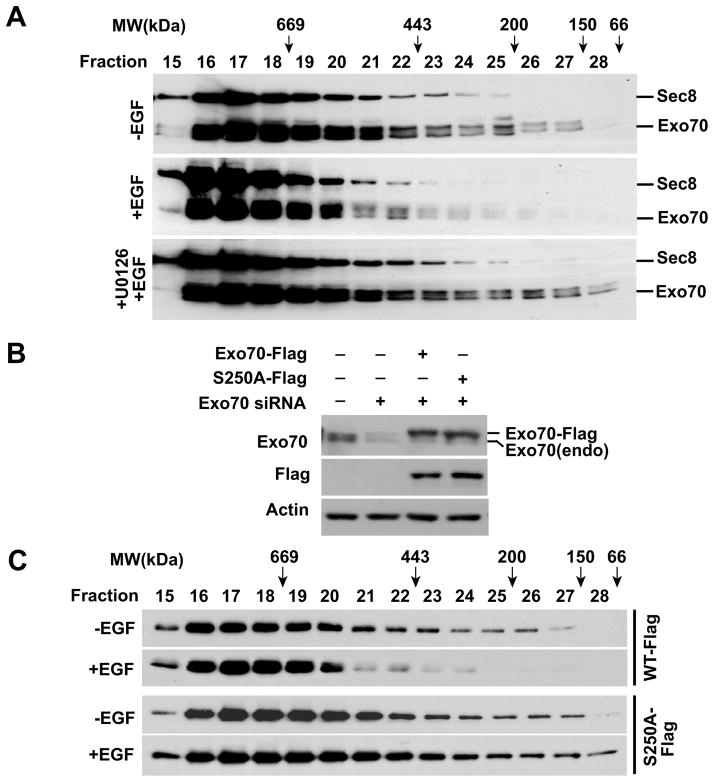

To determine whether Exo70 phosphorylation affects its assembly into the exocyst complex, detergent extracts of HeLa cells were subject to gel-filtration chromatography. Elution fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting using monoclonal antibodies against Exo70 and Sec8. In un-stimulated cells, while a large amount of Exo70 co-migrated with Sec8 in high-molecular weight fractions corresponding to the assembled exocyst complex, a significant amount of Exo70 eluted at the lower molecular weight fractions (Figure 5A). In cells treated with EGF, almost all of the Exo70 proteins appeared in the high-molecular weight fractions. In cells pre-treated with U0126 before EGF stimulation, the shift of Exo70 to higher molecular mass complex was diminished. This result suggests that phosphorylation of Exo70 by ERK1/2 stimulates its assembly into the exocyst complex.

Figure 5. Exo70 phosphorylation promotes exocyst complex assembly.

(A) HeLa cells were treated with EGF for 5 min, or pre-incubated with U0126 for 30 min before EGF treatment. Cell extracts were fractionated on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL gel filtration column and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting with the anti-Sec8 and anti-Exo70 antibodies. The molecular weight standards for the fractions are marked at the top. (B) Western blot showing the levels of Exo70 in cells stably expressing Flag-tagged rat Exo70 and Exo70(S250A) as detected by the anti-Exo70 antibody and anti-Flag antibody. The endogenous Exo70 and Flag-tagged Exo70 are indicated to the right. Actin was used as loading control. (C) The Exo70 knockdown cells expressing Flag-tagged rat Exo70 or Exo70(S250A) were treated with EGF for 5 min, and the lysates were prepared for gel-filtration chromatography. The fractions were collected and analyzed by western blotting using the anti-Flag antibody.

To further confirm that phosphorylation of Exo70 regulates exocyst assembly, we generated HeLa cells stably expressing Flag-tagged rat Exo70 or Exo70 (S250A). The endogenous Exo70 was then knocked down by siRNA targeting human Exo70. The knockdown levels and expression of Flag-tagged Exo70 were analyzed by western blotting (Figure 5B). The cells were treated with EGF for 5 min and the cell lysates were subject to gel filtration chromatography. As shown in Figure 5C, EGF treatment promoted the association of Flag-tagged wild type Exo70, but not the Exo70(S250A) mutant, into the high-molecular weight complex.

Exo70 phosphorylation by ERK1/2 is not involved in its recruitment to the plasma membrane in response to EGF stimulation

Since ERK1/2 is activated in cells after EGF stimulation, we examined whether ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 mediates its plasma membrane-recruitment. HeLa cells expressing Flag-tagged wild type, S250A or S250D mutant Exo70 were treated with EGF for 5 min. The localization of these proteins in cells was then examined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Similar to the wild type and S250D mutant, the S250A mutant was recruited to the plasma membrane in response to EGF (Supplemental Figure 2). As a negative control, the Exo70-K632A/K635A mutant, which is defective in binding to PI(4,5)P2 (Liu et al., 2007), failed to associate with the plasma membrane after EGF stimulation. This result suggests that ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 is not involved in the recruitment of Exo70 to the plasma membrane.

Exo70 phosphorylation is important for MMPs secretion and tumor cell invasion

Previous studies have shown that ERK1/2 signaling is involved in regulating invadopodia formation and MMPs secretion (Kurata et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2000; Takino et al., 2004). However, the underlying mechanism is unclear. The exocyst complex has been implicated in invadopodia formation by mediating the secretion of MMPs (Liu et al., 2009; Sakurai-Yageta et al., 2008). It is thus possible that ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 is involved in invadopodia activity. To test this hypothesis, we used the MDAMB- 231 cell, a commonly used human breast cancer cell line for studying invadopodia, in our study. Cells were plated on Alexa-568-gelatin coated coverslips for 1 hour for attachment, and then treated with either DMSO or 20 μM U0126. The invadopodia activity, observed as areas of Alexa-568-gelatin digestion on the coverslip, was clearly observed in cells treated with DMSO. However, in cells treated with U0126, the activity was greatly reduced (Figure 6A and B). We also tested MMPs secretion in MDA-MB 231 cells using zymography. Culture media from MDA-MB-231 cells treated with DMSO or U0126 were collected and concentrated. The media samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by in-gel digestion assay. Cells treated with U0126 showed significant a reduction of MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion (Figure 6C and D). These data indicate that ERK1/2 signaling regulates invadopodia formation and MMP secretion in MDA-MB-231 cells, consistent with the results obtained previously from the use of other cell lines (Kurata et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2000; Takino et al., 2004).

Figure 6. ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 at S250 is important for invadopodia formation and MMP secretion.

(A) ERK1/2 signaling is required for invadopodia formation. MDA-MB-231 cells treated with DMSO or 20 μM U0126 were cultured on Alexa-568-gelatin coated coverslips. The cells were fixed and stained with Alexa-488-phalloidin (green). The right panel indicates the areas of Alexa-568-gelatin digestion generated by invadopodia (black holes) from these cells. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Quantification of areas of digestion shows that the invadopodia activity was significantly reduced in cells treated with U0126. “A.U.”, arbitrary units. Error bars, SD. *, p<0.01. (C) Effect of U0126 on MMP secretion in MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells treated with DMSO or 20 μM U0126 were incubated with serum-free medium for 16 hrs. The conditioned media were subjected to in gel zymography. (D) Quantification of secreted MMP levels in cells treated with DMSO or 20 μM U0126 were performed using ImageJ software (n=3). Error bars, SD. *, p<0.01. (E) MDA-MB-231 parental cells or cells stably expressing rat Exo70-Flag or Exo70(S250A)-Flag mutant were transfected with siRNA against luciferase or endogenous human Exo70. The cells were cultured on Alexa-568-labeled gelatin matrix for invadopodia formation. The cells were then stained with Alexa-594-phalloidin (blue) together with either the anti-Exo70 antibody (parental cell line, top two panels) or anti-Flag antibody (Exo70-Flag stable cell lines, bottom two panels) (green). Scale bars, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of areas of degradation per cell. Three independent experiments (over 50 cells each) for each treatment were carried out. Error bars, SD. *p<0.05. (G) In-gel zymography analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-9 secreted from the cells. The positions of MMP-2 and MMP-9 on SDS-PAGE are labeled to the right. (H) Quantification of secreted MMP levels were performed by Image J (n=3). Error bars, SD. *p<0.05.

Next, we examined whether Exo70 phosphorylation by ERK1/2 is involved in the regulation of invadopodia activity. Stable MDA-MB-231 cell lines expressing either rat Exo70-Flag or the Exo70(S250A)-Flag mutant were generated. The endogenous Exo70 in these cells was then knocked down by RNAi. In the parental MDA-MD-231 cells transfected with siRNA targeting Exo70, invadopodia invasion, as assayed by the area of degradated Alexa-568-gelatin, was reduced by 47% compared to cells transfected with control siRNA against luciferase (Figure 6E and F). Exo70 knockdown cells expressing rat Exo70-Flag had normal or slightly increased invadopodia invasion. However, knockdown cells expressing Exo70(S250A)-Flag showed lower invadopodia activity (Figure 6E and F). We also tested whether MMPs secretion was affected in cells expressing the Exo70(S250A) mutant. As shown in Figure 6G and H, knockdown of Exo70 significantly decreased the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9. Exo70 knockdown cells expressing rat Exo70 secreted MMPs at a level similar to the cells treated with luciferase siRNA, whereas cells expressing Exo70(S250A) showed reduced levels of MMP secretion. Together, these data suggest that ERK1/2 phosphorylation on Exo70 Serine 250 plays an important role in MMPs secretion and tumor cell invasion.

DISCUSSION

Our study identified the exocyst subunit Exo70 as a direct substrate of ERK1/2. Exo70 is phosphorylated by ERK1/2 in response to EGF signaling in cells. Experiments using U0126 and different Exo70 phospho-mutants suggest that ERK1/2 phosphorylation of Exo70 stimulates exocytosis. Tumor cell invasion requires exocytosis of MMPs to destroy the extracellular matrix, and ERK1/2 has been shown to regulate this process (Badowski et al., 2008). Here using the invadopodia assay, we demonstrate that the phosphorylation of Exo70 at S250 regulate MMP secretion and invadopodia activity.

The exocyst is thought to function in vesicle tethering, a step prior to SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Exo70 is a pivotal subunit in the exocyst complex as it directly interacts with PI(4,5)P2 through its C-terminus and is implicated in the targeting of the exocyst to the plasma membrane (He et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007). Here we found that phosphorylation of Exo70 by ERK1/2 stimulates its interaction with Sec8 and Exo84, and promotes its assembly into the exocyst complex. Our work shows that, in response to extracellular stimuli, the assembly of the exocyst complex can be regulated by phosphorylation of its subunit. Based on the yeast and mouse Exo70 crystal structures, S250 localizes in a flexible region between Helix 6 and Helix 7 involved in binding to other exocyst components (Moore et al., 2007). It is possible that phosphorylation of S250 leads to conformational changes of Exo70, yielding better accessibility to the other exocyst components for complex assembly.

EGF has also been shown to stimulate the recruitment of Exo70 to the plasma membrane (Zuo et al., 2006). However, ERK1/2 do not seem to be involved in the membrane recruitment of Exo70 as the phospho-deficient Exo70(S250A) mutant can still be localized to the plasma membrane in response to EGF (Supplemental Figure 2). In addition to ERK1/2 phosphorylation reported here, the exocyst is also an effector of a number of small GTPases (for review, see (He and Guo, 2009; Lipschutz and Mostov, 2002; Novick and Guo, 2002). Exo70 was previously shown to interact with TC10, a close homologue of Cdc42 that functions downstream of EGF (Inoue et al., 2003; Kawase et al., 2006). Expression of a constitutively activated TC10 mutant, TC10(Q75L), drives the recruitment of Exo70 to the plasma membrane (Inoue et al., 2003). In fact, the phospho-deficient Exo70 mutant can still be recruited to the plasma membrane in cells expressing the activated form of TC10 (Supplemental Figure 3). Our data suggest that ERK1/2 specifically affects the interaction of Exo70 with other exocyst subunits rather than its recruitment to the plasma membrane. TC10 and ERK1/2 may regulate different aspects of Exo70 function. It is interesting to note that the N-terminus deleted Exo70 was better phosphorylated than the full-length Exo70 in vitro (Figure 1G). It is likely that Exo70 is activated in a multi-step process, in which Exo70 first undergoes conformational changes so that S250 can be better accessed by ERK1/2. However, it remains unclear what is the early step activator. It will be interesting to investigate how the regulatory effects of TC10, ERK1/2, and other potential regulators of Exo70 are coordinated.

In addition to being a direct substrate of ERK1/2, members of the exocyst have also been directly and indirectly linked to other kinases. Sec5 can be phosphorylated by PKC, which leads to the dissociation of the exocyst from RalA for its recycling (Chen et al., 2011). The exocyst complex can also be co-immunoprecipitated with atypical PKC (aPKC); the aPKC-exocyst complex regulates the phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins for cell migration (Rosse et al., 2009). Interestingly, ERK1/2 was shown to be involved in the regulation of the aPKC-exocyst complex-mediated migration, although the mechanism is not clear (Boeckeler et al., 2010). The exocyst has also been implicated in tumorigenesis together with Ral. The Ral-exocyst complex functions upstream or as a scaffold for the activation of TBK and HGK, which play important roles in cancer (Chien et al., 2006; Balakireva et al., 2006). Recently, it was shown that RalB induces the assembly of catalytically active ULK1 and Beclin1-VPS34 complexes on the exocyst, which are required for isolation membrane formation and maturation (Bodemann et al., 2011). Together, these studies demonstrate an intimate connection of the exocyst with signaling networks in cells.

While our study focuses on the effect of ERK1/2 in the EGF signaling pathway, it is likely that such regulatory mechanisms also operate in response to other growth factors or hormones such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and insulin. As the exocyst is involved in many processes such as epithelial polarity, neurite branching, and tumorigenesis (for reviews see (Bryant and Mostov, 2008; Hall and Lalli; Nelson and Yeaman, 2001), phosphorylation of Exo70 by ERK1/2 likely plays pivotal roles in these cellular processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and cell culture

The sources of the antibodies used were as follows: monoclonal antibodies against Flag M2 (Sigma-Aldrich), ERK1/2, Phospho-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 substrate (Cell Signal, Inc.). The 8G5 monoclonal antibody against the extracellular domain of VSV-G was kindly provided by Dr. Douglas Lyles (Wake Forest University). Sec8, Exo84 and Exo70 antibodies were generous gifts from Dr. Shu-Chan Hsu (Rutgers University). Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluro 594 were purchased from Invitrogen, and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from GE Healthcare. EGF was purchased from Roche and used at 50 ng/ml in the cell culture. U0126 was purchased from Cell Signal, Inc. and was used at 10 μM in the experiments. HeLa cells stably expressing Flag-tagged Exo70 variants were generated by selection with G418 at a concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Recombinant proteins and in vitro kinase assays

Wild type Exo70, Exo70(S250A) and Exo70(S250D) mutant were expressed as GST fusion proteins in the pGEX-6P vector and purified from bacteria lysates with glutathione resin (GE Healthcare). The GST tag was removed by PreScission protease. Recombinant Exo70 proteins were incubated with HISx6-ERK2-CA (constitutively active) or HISx6-ERK2-KD (kinase dead) purified from E.coli in the kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM NaF, and 1 mM PMSF) in the presence of 10 μCi [32P] γ-ATP for 30 min at 30°C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The plasmids for co-expression of MEK1 with ERK2 and for the kinase-dead version of ERK2 were generously provided by Dr. Melanie Cobb (UT Southwestern Medical Center) (Khokhlatchev et al., 1997).

Immunoprecipitation and binding assay

Immunoprecipitation and in vitro binding assay were performed as previously described (Zuo et al., 2006). For immunoprecipitation, cells were solubilized in the NP-40 extraction buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 1 mM NaF, and 1 mM NaVO4) containing protease inhibitors cocktail after treatment. Lysates were then cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Equal amounts of proteins were incubated with antibodies for 2 hours at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitated complexes were collected and washed four times with extraction buffer. Proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis.

VSV-G trafficking assay

VSV-G trafficking assay was performed as described previously (Liu et al., 2007). Briefly, HeLa cells were transfected with VSV-G-45ts-GFP mutant and incubated at 40°C. After overnight growth, the cells were moved to 20°C for 2 hours for Golgi arrest and then shifted to 32°C for different times in the presence of 100 μg/ml Cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) for post-Golgi trafficking. The cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 12 min, washed, and blocked for 10 min with 5% bovine serum albumin. The cover slips were then incubated with the 8G5 monoclonal antibody against the extracellular domain of VSV-G. No detergent was used in the immunofluorescence procedure. To specifically examine the role of ERK1/2 in the Golgi-to-cell surface stage of trafficking, the cells were pre-treated with U0126 for 30 min before releasing the VSV-G ts045 protein trafficking at 32°C. To examine VSV-G transport in Exo70 mutants, HeLa cells were treated with siRNA targeting human EXO70 as previously described (Liu et al. 2007), and then co-transfected with ts045-VSV-G-GFP with Flag-tagged rat Exo70, Flag-Exo70(S250A), and Flag-Exo70(S250D). Cells expressing Exo70 variants were identified by immunofluorescence with an anti-Flag polyclonal antibody followed by Alexa-633-conjugated secondary antibody (Cell Signaling, Inc.), and VSV-G-GFP transport was examined in these cells. Quantification of the VSV-G surface incorporation was performed in confocal sections with average intensity using ImageJ software. Total GFP-VSV-G and surface stained fluorescence signal intensity were measured and subtracted from the same background signal of the same picture. VSV-G cell surface incorporation is presented as the ratio of cell surface antibody staining fluorescence to total VSV-G-GFP fluorescence of the cell.

Fluorescence microscopy

For immunofluorescence staining of Exo70 variants and F-actin, HeLa cells were starved for 16 hours and treated with 50 ng/ml EGF for 5 min. The cells were then fixed with 4% fresh paraformaldehyde. The anti-Flag monoclonal antibody was used at 1:1000 for Flag-tagged Exo70 proteins. Rhodamine-phalloidin was used for F-actin staining. For fluorescence observation, a Leica TCS SL laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica, Deerfield, IL) was used at 63x objective and with 4 x magnification.

Gel filtration chromatography

Gel filtration was performed at 4°C on a Superdex 200 10/300 column driven by an AKTA FPLC system (GE healthcare). Cells were lysed by the lysis buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1 % NP-40, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, phosphatase inhibitors mixture, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min to collect the supernatant. The column was equilibrated with the lysis buffer and then loaded with 0.25 ml of cell lysates. 0.5 ml fractions were collected at flow rate 0.5 ml/min. The column was calibrated with molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad). The fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

Invadopodia extracellular matrix degradation assay

Gelatin (Sigma) was labelled with Alexa Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes, inc.) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Coverslips were acid-washed and coated with 50 μg/ml poly-L-lysine for 15 min, washed with PBS, and crosslinked with 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 15 min. The coverslips were then inverted on an 80 μl drop of 1 mg/ml Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated gelatin for 10 min. After washing with PBS, the coverslips were quenched with 5 mg/mL sodium borohydride for 10 min followed by another wash with PBS. The coverslips were then incubated in the growth medium for 1 hour before use. To assay for invasion, cells were cultured on fluorescent conjugated matrix for 12 hours, and then fixed with 10% formalin and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min, labeled with primary antibodies for 2 hours followed by labeling with secondary fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Actin filaments were visualized with Alexa-phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Inc). Cells were imaged with the Leica DM IRB microscope (Deerfield, IL) using the 63x objective. Quantification of the degradation area was done by ImageJ and after subtracted from the background signal of the same field as described before (Liu et al., 2009). The degradation percentage was normalized to control parental cells transfected with siRNA against luciferase. Quantification was done in at least three independent experiments in duplicates for each assay.

The in-gel gelatin zymography assay for MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity was performed as described previously (Liu et al., 2009). Briefly, MBA-MD-231 cell media were collected and concentrated. The samples were mixed with SDS loading buffer and separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.3% gelatin. The gel was then washed twice in 2.5% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight at 37°C in the MMP reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 10 mM CaCl2), stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and destained to detect areas of gelatin degradation in the gel.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

ERK1/2 stimulatesexocytosis.

ERK1/2 phosphorylates Exo70 at Ser250.

Exo70 phosphorylation promotesthe exocyst complex assembly.

Exo70 phosphorylation regulates MMPs secretion and invadopodia formation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Melanie Cobb (UT Southwestern Medical Center) for providing us with the plasmids for the MEK1 and ERK2 expression used in our in vitro kinase assays. We also thank Drs. Shu-chan Hsu (Rutgers University) and Douglas Lyles (Wake Forest University) for antibodies against the exocyst subunits and VSV-G. We are grateful to Yujuan Hong and Jian Zhang for many technical helps, to Drs. Jianglan Liu and John Schmidt for technical advice and reading the manuscript. This work is supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (GM-064690 and GM-085146) and American Heart Association to WG.

Abbreviations

- ERK1/2

Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- VSV-G

vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FPLC

Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography

- MMP

Matrix Metalloproteinase

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Badowski C, Pawlak G, Grichine A, Chabadel A, Oddou C, Jurdic P, Pfaff M, Albiges-Rizo C, Block MR. Paxillin phosphorylation controls invadopodia/podosomes spatiotemporal organization. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:633–645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP. A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1285–1292. doi: 10.1038/nbt1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzat A, Hall A. Cellular responses to extracellular guidance cues. EMBO J. 29:2734–2745. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisel B, Wang Y, Wei JH, Xiang Y, Tang D, Miron-Mendoza M, Yoshimura S, Nakamura N, Seemann J. ERK regulates Golgi and centrosome orientation towards the leading edge through GRASP65. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:837–843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodemann BO, Orvedahl A, Cheng T, Ram RR, Ou YH, Formstecher E, Maiti M, Hazelett CC, Wauson EM, Balakireva M, et al. RalB and the exocyst mediate the cellular starvation response by direct activation of autophagosome assembly. Cell. 2011;144:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckeler K, Rosse C, Howell M, Parker PJ. Manipulating signal delivery - plasma-membrane ERK activation in aPKC-dependent migration. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2725–2732. doi: 10.1242/jcs.062299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant DM, Mostov KE. From cells to organs: building polarized tissue. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:887–901. doi: 10.1038/nrm2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XW, Leto D, Xiao J, Goss J, Wang Q, Shavit JA, Xiong T, Yu G, Ginsburg D, Toomre D, et al. Exocyst function is regulated by effector phosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:580–588. doi: 10.1038/ncb2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Saidon C, Cohen AA, Sigal A, Liron Y, Alon U. Dynamics and variability of ERK2 response to EGF in individual living cells. Mol Cell. 2009;36:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G, Hutagalung AH, Fu C, Novick P, Reinisch KM. The structures of exocyst subunit Exo70p and the Exo84p C-terminal domains reveal a common motif. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1094–1100. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhan H, Rabouille C. Signalling to and from the secretory pathway. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:171–180. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhan H, Wendeler MW, Mitrovic S, Fava E, Silberberg Y, Sharan R, Zerial M, Hauri HP. MAPK signaling to the early secretory pathway revealed by kinase/phosphatase functional screening. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:997–1011. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Sacher M, Barrowman J, Ferro-Novick S, Novick P. Protein complexes in transport vesicle targeting. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:251–255. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A, Lalli G. Rho and Ras GTPases in axon growth, guidance, and branching. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2:a001818. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Guo W. The exocyst complex in polarized exocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Xi F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Guo W. Exo70 interacts with phospholipids and mediates the targeting of the exocyst to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 2007;26:4053–4065. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SC, TerBush D, Abraham M, Guo W. The exocyst complex in polarized exocytosis. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;233:243–265. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)33006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Chang L, Hwang J, Chiang SH, Saltiel AR. The exocyst complex is required for targeting of Glut4 to the plasma membrane by insulin. Nature. 2003;422:629–633. doi: 10.1038/nature01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesch SA, Lewis TS, Ahn NG, Linstedt AD. Mitotic phosphorylation of Golgi reassembly stacking protein 55 by mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK2. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1811–1817. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase K, Nakamura T, Takaya A, Aoki K, Namikawa K, Kiyama H, Inagaki S, Takemoto H, Saltiel AR, Matsuda M. GTP hydrolysis by the Rho family GTPase TC10 promotes exocytic vesicle fusion. Dev Cell. 2006;11:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlatchev A, Xu S, English J, Wu P, Schaefer E, Cobb MH. Reconstitution of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation cascades in bacteria. Efficient synthesis of active protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11057–11062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemke RL, Cai S, Giannini AL, Gallagher PJ, de Lanerolle P, Cheresh DA. Regulation of cell motility by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:481–492. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno M, Pouyssegur J. Targeting the ERK signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Ann Med. 2006;38:200–211. doi: 10.1080/07853890600551037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolch W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrm1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata H, Thant AA, Matsuo S, Senga T, Okazaki K, Hotta N, Hamaguchi M. Constitutive activation of MAP kinase kinase (MEK1) is critical and sufficient for the activation of MMP-2. Exp Cell Res. 2000;254:180–188. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit T, Pilot F. Developmental control of cell morphogenesis: a focus on membrane growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:103–108. doi: 10.1038/ncb0203-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancois L, Lyles DS. The interaction of antibody with the major surface glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus. II. Monoclonal antibodies of nonneutralizing and cross-reactive epitopes of Indiana and New Jersey serotypes. Virology. 1982;121:168–174. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipschutz JH, Mostov KE. Exocytosis: the many masters of the exocyst. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R212–214. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu E, Thant AA, Kikkawa F, Kurata H, Tanaka S, Nawa A, Mizutani S, Matsuda S, Hanafusa H, Hamaguchi M. The Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is critical for the activation of matrix metalloproteinase secretion and the invasiveness in v-crk-transformed 3Y1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2361–2364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yue P, Artym VV, Mueller SC, Guo W. The role of the exocyst in matrix metalloproteinase secretion and actin dynamics during tumor cell invadopodia formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3763–3771. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zuo X, Yue P, Guo W. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate mediates the targeting of the exocyst to the plasma membrane for exocytosis in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4483–4492. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellman I, Nelson WJ. Coordinated protein sorting, targeting and distribution in polarized cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:833–845. doi: 10.1038/nrm2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Robinson HH, Xu Z. The crystal structure of mouse Exo70 reveals unique features of the mammalian exocyst. J Mol Biol. 2007;371:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson M, Novick P. The exocyst defrocked, a framework of rods revealed. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:577–581. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WJ, Yeaman C. Protein trafficking in the exocytic pathway of polarized epithelial cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:483–486. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P, Guo W. Ras family therapy: Rab, Rho and Ral talk to the exocyst. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:247–249. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando K, Guo W. Membrane organization and dynamics in cell polarity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001321. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullikuth AK, Catling AD. Scaffold mediated regulation of MAPK signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics: a perspective. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1621–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajalingam K, Rudel T. Ras-Raf signaling needs prohibitin. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1503–1505. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai-Yageta M, Recchi C, Le Dez G, Sibarita JB, Daviet L, Camonis J, D’Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. The interaction of IQGAP1 with the exocyst complex is required for tumor cell invasion downstream of Cdc42 and RhoA. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:985–998. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su T, Bryant DM, Luton F, Verges M, Ulrich SM, Hansen KC, Datta A, Eastburn DJ, Burlingame AL, Shokat KM, et al. A kinase cascade leading to Rab11-FIP5 controls transcytosis of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1143–1153. doi: 10.1038/ncb2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takino T, Miyamori H, Watanabe Y, Yoshioka K, Seiki M, Sato H. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase regulates collagen-dependent mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-related kinase activation and cell migration. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1044–1049. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Hsu SC. The molecular mechanisms of the mammalian exocyst complex in exocytosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:687–690. doi: 10.1042/BST0340687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Seemann J, Pypaert M, Shorter J, Warren G. A direct role for GRASP65 as a mitotically regulated Golgi stacking factor. EMBO J. 2003;22:3279–3290. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura S, Yoshioka K, Barr FA, Lowe M, Nakayama K, Ohkuma S, Nakamura N. Convergence of cell cycle regulation and growth factor signals on GRASP65. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23048–23056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Hsu SC, Zhou D, Guo W. Exo70 interacts with the Arp2/3 complex and regulates cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1383–1388. doi: 10.1038/ncb1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.