Abstract

Most bacterial genomes harbor restriction–modification systems, encoding a REase and its cognate MTase. On attack by a foreign DNA, the REase recognizes it as nonself and subjects it to restriction. Should REases be highly specific for targeting the invading foreign DNA? It is often considered to be the case. However, when bacteria harboring a promiscuous or high-fidelity variant of the REase were challenged with bacteriophages, fitness was maximal under conditions of catalytic promiscuity. We also delineate possible mechanisms by which the REase recognizes the chromosome as self at the noncanonical sites, thereby preventing lethal dsDNA breaks. This study provides a fundamental understanding of how bacteria exploit an existing defense system to gain fitness advantage during a host–parasite coevolutionary “arms race.”

Keywords: evolution, KpnI, promiscuous activity, DNA cleavage, genome protection

Molecular recognition between enzymes and their substrates and/or the cofactors govern physiological functions. Specificity in substrate recognition is considered crucial, whereas promiscuity is often associated with suboptimal catalytic properties. Typically, active site residues are involved during promiscuous catalytic activity, and the mechanism of catalysis used is similar, despite flexibility in substrate occupancy (1). It has long been known that many enzymes exhibit flexibility in substrate recognition (2, 3). The high specificity, however, is considered a cornerstone of enzyme catalysis, and attempts have often been made to increase the fidelity in vitro by either directed evolution or site-directed mutagenesis (1, 4–6). Although promiscuity is thought to play a role in divergence of enzyme function (7), retention of broad specificity in nature, as opposed to the high specificity for many enzymes, continues to be a paradox.

Restriction–modification (R-M) systems are one of the largest groups of enzymes that exhibit a high degree of sequence specificity for their target sequences. The components of the R-M systems, namely, REase and MTase, show wide diversity vis-à-vis their recognition patterns, active site architecture, and reaction mechanisms (8). The REases recognize and cleave specific dsDNA sequences that are extraneous, whereas the MTase activity transfers a methyl group to the same DNA sequence within the host’s genome to allow discrimination between self and nonself DNA. R-M systems thus serve as primitive “innate” immune systems that provide 102- to 108-fold protection for the host cell against invading bacteriophages and other genetic elements (9, 10). The innateness is attributed to the high specificity of the REases, which cleave the foreign DNA at the canonical sites several orders of magnitude more readily than at the noncanonical sequences. The immaculate specificity achieved by REases has been a subject of extensive study using biochemical, thermodynamic, and structural approaches (8, 11–13). Physiologically, the exquisite specificity is considered an important virtue of these enzymes to target the invading genomes better.

Studies carried out with R.KpnI, a type II REase, opened up a different perspective on this prevailing theme, because the enzyme exhibits highly promiscuous cleavage under certain conditions (14). The REase exhibits remarkable versatility in substrate recognition and cofactor utilization, whereas the cognate MTase is very site-specific (14). In addition to its recognition sequence, GGTACC, the enzyme binds and cleaves a number of noncanonical sequences (i.e., TGTACC, GTTACC, GATACC, GGAACC, GGTCCC, GGTATC, GGTACG, GGTACT), with the binding affinity ranging from 8 to 35 nM (14, 15). Accordingly, many of these sites are cleaved efficiently with kcat values varying from 0.06 to 0.15 min−1 vs. 4.3 min−1 for canonical sites (15). The promiscuous activity of the enzyme is directed by a number of cofactors. In the presence of the physiological levels of Mg2+, the most abundant cofactor present in the cell (16) and typically required for the activity of REases, R.KpnI discriminates poorly between the canonical and noncanonical sequences, indicating that the promiscuity is an intrinsic property of the enzyme (15). It is intriguing why promiscuity is manifested and what would be its biological significance for the organism. Is it an evolutionary event that remained vestigial, or was it retained with a purpose? The present study examines the in vivo manifestation of promiscuity and the conditions that drive it. We provide evidence for the selective advantage for bacteria in retention of the promiscuous activity because it confers additional protection against the invading genomes. Targeting the incoming genetic elements at the noncanonical sites counters the two common antirestriction strategies, namely, modification of phage genome and decrease in R-M recognition sites, and highlights a winning situation for bacteria in the evolutionary “arms race” between them and their parasites.

Results

In Vivo Promiscuous Activity Confers Better Protection.

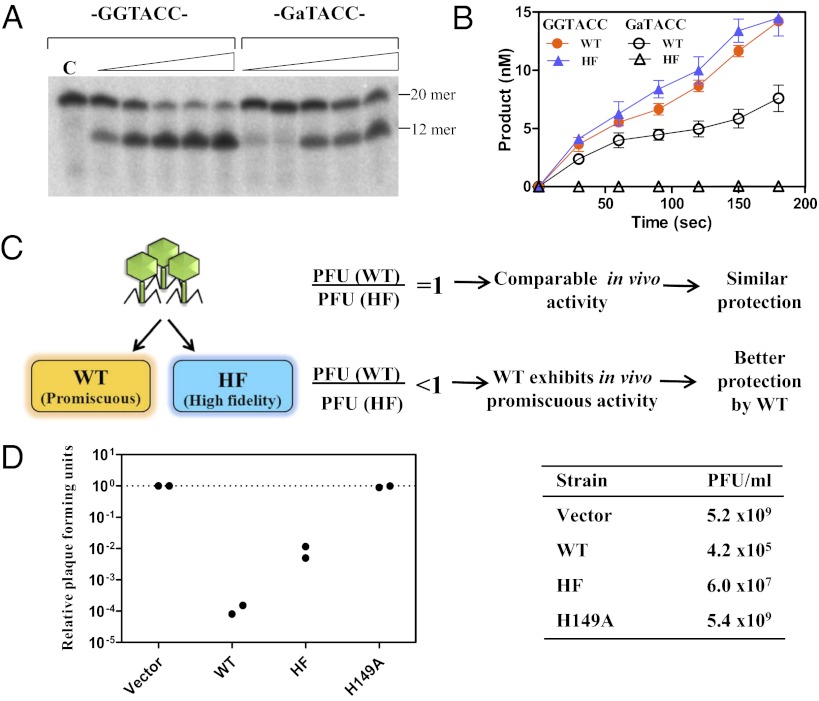

Given the robust in vitro promiscuous activity of R.KpnI beyond a concentration of 1 mM Mg2+ (17), we considered its potential to cleave noncanonical DNA sequences in vivo. The total intracellular Mg2+ concentration could vary from 5–10 mM, with the free intracellular concentration reaching up to 2 mM (16, 18), which is sufficient to elicit promiscuous cleavage. The REase isolated from Klebsiella pneumoniae, which harbors the KpnI R-M system, was tested for its activity on noncanonical DNA substrates. R.KpnI from the native source exhibited biochemical properties similar to those of the enzyme overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Notably, promiscuous DNA cleavage was observed (Fig. 1A), indicating the inherent promiscuous nature of the REase.

Fig. 1.

Promiscuous activity of KpnI REase confers better protection. (A) Oligonucleotides (10 nM, 5′ end-labeled) containing a canonical sequence (-GGTACC-) or one of the most preferred noncanonical sequences (-GaTACC-) were incubated with Mg2+ and different dilutions of cell-free extracts of K. pneumoniae strain OK8 for 30 min at 37 °C and analyzed on an 8 M urea – 12% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel. The enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage of the 20-mer substrate generates a 12-mer end-labeled product. Lane C is substrate DNA with no enzyme. (B) Rates of DNA cleavage by WT and HF enzymes were assayed in the presence of canonical and noncanonical substrates. Reactions contained 1 nM (for canonical DNA cleavage) or 15 nM (for noncanonical DNA cleavage) of the enzyme and 100 nM of substrate in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4). The reactions were initiated by the addition of 2 mM Mg2+ and incubation at 37 °C for different time intervals. The plot depicts the product formed vs. time. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (C) Experimental design of the phage titration assay. Plaque-forming units (PFU) with cells harboring WT and HF were compared. A similar PFU count on both of the strains would indicate a comparable restriction by the WT and HF variants. Alternatively, a lower PFU count on WT-harboring cells compared with the HF variant would indicate greater protection against phages. (D) P1vir phage restriction by R.KpnI and its variants. The plaque-forming units of P1vir phage on cells harboring the WT, the HF variant, or the catalysis-deficient mutant (H149A) relative to cells containing empty vector are shown. (Left) Values from two independent experiments conducted in quadruplicate are plotted. (Right) Representative titer values are shown.

To investigate a potential role for in vivo promiscuous activity, we took advantage of a point mutant of R.KpnI, D163I, which exhibits high-fidelity (HF) DNA cleavage (17). The HF variant did not show any promiscuous behavior even at high enzyme or Mg2+ concentrations but exhibited a cleavage rate comparable to the WT enzyme at the canonical sequences (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1).

Because the primary function of R-M systems is to restrict the xenogeneic DNA and protect the host from potent invading life forms, such as bacteriophages (19, 20), phage titer analysis gives an in vivo measurement of the REase activity (Fig. 1C). To investigate whether the recognition of noncanonical sequences confers better protection against phages, P1vir phage was used as an infectious genome element and E. coli BL26 (DE3) MK+ strain harboring either R.KpnI WT (pETRK-WT) or HF (pETRK-HF) was used as a host (Table 1). Phage titer assays revealed that the efficiency of plating (EOP) on strains harboring WT or HF enzymes was two to four orders of magnitude lower than on those lacking the REase or harboring a catalytically deficient mutant of REase, suggesting effective restriction of the invading phage by R.KpnI (Fig. 1D). However, a two orders of magnitude better restriction of the infecting phage DNA is observed with cells containing WT REase compared with the HF enzyme. A more effective restriction of the phage by WT could be attributed to either of two reasons: The enzyme exhibits cleavage at noncanonical sites in addition to the canonical sequences, or it possesses higher activity at canonical sequences compared with the HF variant. Kinetic analysis with the WT and HF variants of R.KpnI revealed that the enzymes possess a comparable turnover value for the canonical recognition sites (Table 2). This suggested that the WT REase recognizes additional sequences on the phage genome.

Table 1.

Plasmids and strains used in this study

| Plasmids/strains | Characteristics |

| pETRK-WT | R.KpnI cloned into pET11d between NcoI and BamHI sites |

| pETRK-HF | R.KpnI D163I cloned into pET11d between NcoI and BamHI sites |

| pACMK | M.KpnI cloned into pACYC between EcoRV and HindIII |

| pUCMK | M.KpnI cloned into pUC18 between HincII and HindIII |

| pACR-M | KpnI R-M system with its own promoter elements cloned into pACYC between HindIII and BamHI |

| pEcHNS | E. coli hns cloned into pET16b |

| pEcHU | E. coli hupA and hupB cloned into pRLM118 |

| pEcFIS | E. coli fis cloned into pUHE |

| pUC18 | Plasmid containing a single KpnI site (GGTACC) |

| pUCΔK | pUC18 plasmid lacking the KpnI site (generated by deleting the KpnI site from pUC18 by digesting with EcoRI and HindIII) |

| pBR322 | Plasmid devoid of KpnI sites |

| K. pneumoniae strain OK8 | American Type Culture Collection 4970 strain containing KpnI R-M system |

| E. coli DH10B | Δ(mrr-hsd rms-mcrBC) mcrA recA1 |

| E. coli BL26(DE3) | F-ompT gal [dcm] [lon] hsdSB (rB-, mB-) Δlac (DE3) nin5 lacUV5-T7 gene 1 |

| E. coli DH10B MK(+) | E. coli DH10B harboring pACMK plasmid |

| E. coli BL26(DE3) MK(+) | E. coli BL26(DE3) harboring pACMK plasmid |

| Bacteriophage P1vir | E. coli phage containing 25 sites for KpnI on the genome |

| Bacteriophage λvir | E. coli phage containing 2 sites for KpnI on the genome |

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of WT and HF variants

|

KM, nM |

kcat, min−1 |

kcat/KM, M−1⋅s−1* |

||||

| Substrates | WT | HF | WT | HF | WT | HF |

| (-GGTACC-) | 18 | 22 | 4.56 | 3.38 | 4.2 (±0.3) × 106 | 2.5 (±0.5) × 106 |

| (-Ga/tTACC-) | 53 | nd | 0.16 | nd | 5.0 (±0.8) × 104 | nd |

nd, no detectable cleavage.

*Values are determined from three measurements and are shown as mean ± SE.

Promiscuous Activity Counters the Antirestriction Strategies.

Bacteriophages and other invasive genome elements use several strategies to evade restriction by host REases. One of these strategies is to decrease effective REase recognition sites in the genome either by accumulation of point mutations or by acquisition of DNA modification genes (10, 20, 21). Because phage restriction efficiency of a REase is directly proportional to the number of its recognition sites in the genome, these antirestriction strategies would allow perpetuation of the foreign DNA in bacteria and increase the fitness of the phage (22). If that is the case, cells harboring an HF variant would no longer be effective in restricting the modified phage, whereas the promiscuous WT REase would still be effective and decrease the EOP.

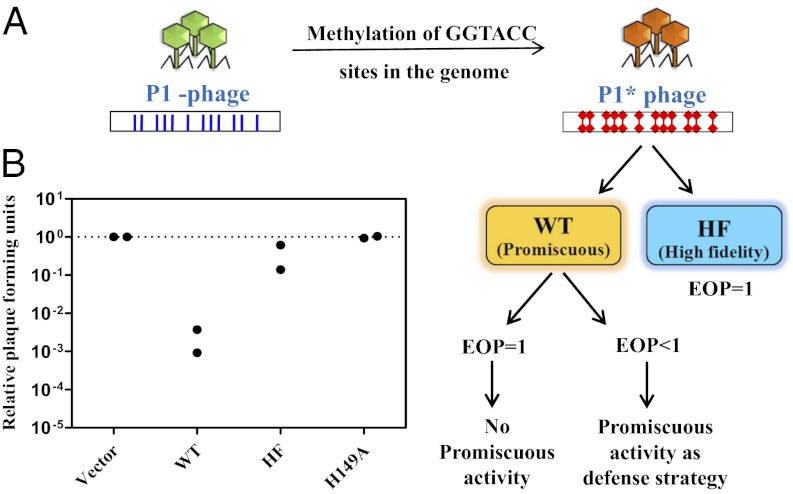

To test the prediction, E. coli BL26 (DE3) MK+ cells harboring WT (pETRK-WT) or HF (pETRK-HF) variant REase were challenged with phage P1vir modified at canonical sequences (Materials and Methods). The modified phage (P1*) is poorly restricted by the cells harboring the HF REase (Fig. 2). In contrast, the P1* population was reduced to <1% by the strains harboring the WT enzyme, indicating that the relaxed cleavage specificity of R.KpnI confers additional protection against the invading genomes. To determine whether the observed features are independent of the number of KpnI sites in the foreign genome(s), titrations were carried out with the bacteriophage λvir, which contains only two GGTACC sites in the genome. The analysis with the λvir (unmodified) and λ* (modified) substantiated the role of promiscuous activity in providing a fitness advantage to bacteria in a phage-enriched environment (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Promiscuous activity counters the antirestriction strategies. (A) Experimental design of phage titration assay with modified phage. Phage P1* (methylated at GGTACC sites in the genome) was prepared with the KpnI MTase overexpression strain as described in Materials and Methods. The HF variant should not restrict the modified phage, whereas the cells harboring a promiscuous WT REase would still decrease the EOP. (B) Plaque-forming units of phage P1* on cells harboring the WT, HF, or catalysis-deficient mutant (H149A) relative to cells harboring empty vector are shown. The measurements from two separate experiments conducted in quadruplicate are plotted.

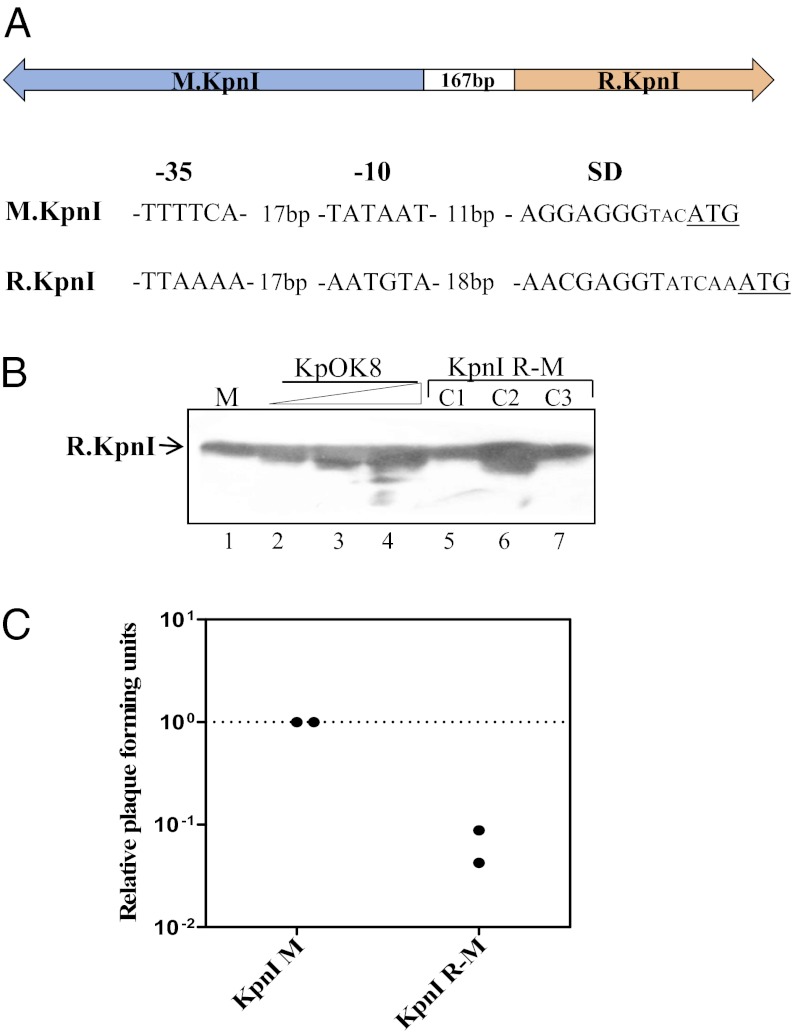

To provide further support for our hypothesis that catalytic promiscuity induced by physiological levels of the REase results in more proficient restriction of phages, titrations were carried out in an E. coli DH10B strain containing a low-copy-number plasmid that harbors a kpnI R-M system (Table 1) with its own promoter and regulatory elements. The genes for KpnI REase and MTase are arranged divergently and separated by a 167-bp intergenic region that contains all the regulatory elements required for the expression of both the genes (23) (Fig. 3A). The promoters are separated by 57 bp and are present in opposite strands having typical characteristic features of σ 70 promoters of E. coli (24, 25). The REase expression with its native promoter in the low-copy plasmid was comparable to that of its level in K. pneumoniae strain OK8 (Fig. 3B), and the strain could restrict P1vir phage methylated at GGTACC sites (Fig. 3C). The low transformation efficiency of the strain with pBR322, which lacks the R.KpnI recognition site (Fig. S2), confirms that the endogenous levels of the REase are sufficient for promiscuous activity against foreign genomes.

Fig. 3.

In vivo analysis of KpnI R-M system-containing cells. (A) Organization of KpnI R-M system. (B) Western blot analysis with R.KpnI polyclonal antibodies. In lane 1, 0.2 μg of purified R.KpnI was used as a marker (M). In lanes 2–4, increasing amounts (250, 500, and 750 μg) of total protein from K. pneumoniae strain OK8 cell lysate (KpOK8) were used. In lanes 5–7, cell lysates (250 μg) prepared from three individual clones of E. coli cells expressing both MTase and REase from their respective endogenous promoters (KpnI R-M) are shown. (C) Phage P1* titer on E. coli cells harboring KpnI MTase alone (KpnI M) or both KpnI MTase and REase (KpnI R-M). The measurements from two separate experiments conducted in quadruplicate are shown.

Catalytic Versatility Confers Fitness Advantage.

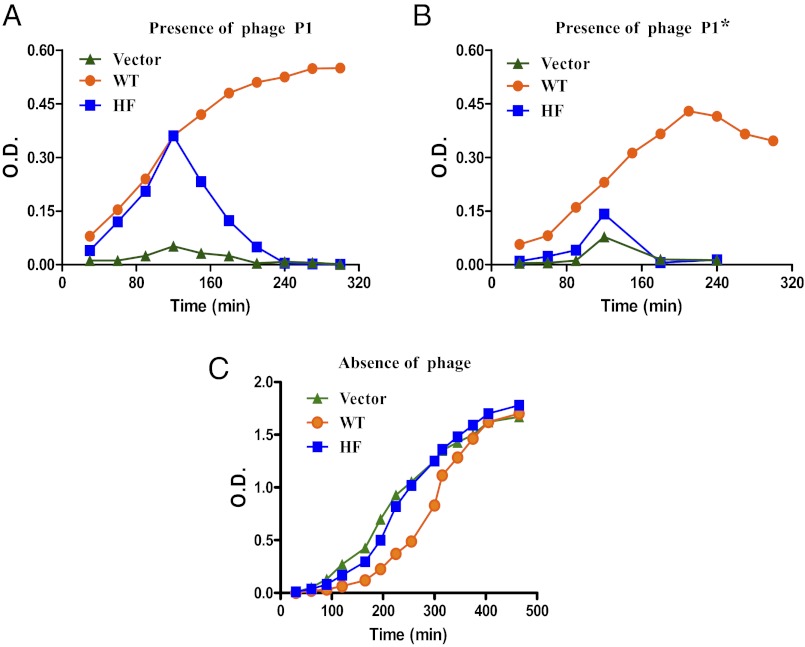

The ability of the enzyme to recognize and cleave noncanonical sequences in vivo confers additional protection to the host against the modified infectious genome elements. To investigate whether this enhanced resistance conferred by the promiscuity increases bacterial survival, growth studies were carried out in the presence of phages (Fig. 4). When E. coli BL26 (DE3) MK+ strains harboring vector (pET11d) or constructs encoding WT (pETRK-WT) or HF (pETRK-HF) enzyme were challenged with unmethylated (P1vir) and methylated (P1*) phages, cells containing only the vector lysed readily (Fig. 4 A and B). Cells expressing the HF variant undergo phage-induced cell lysis with different degrees of susceptibility. With phage P1vir (unmodified) infection, delayed lysis is observed compared with phage P1* (modified). In contrast, WT enzyme-harboring cells did not undergo phage-induced cell lysis for up to 5 h, irrespective of methylation status of the phage. These results correlated with the EOP observed for P1vir and P1* phage on cells harboring vector, WT enzyme, or HF enzyme, substantiating that promiscuity increases fitness advantage during a phage encounter.

Fig. 4.

Catalytic versatility confers fitness advantage. Growth profiles of E. coli BL26 cells harboring vector, the WT, or the HF variant in the presence of P1vir (A) or P1* (P1vir phage methylated at KpnI sites) (B). (C) Growth curve analysis of the cells in the absence of phage. Growth was monitored at OD600. Growth curves shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Self vs. Nonself Recognition.

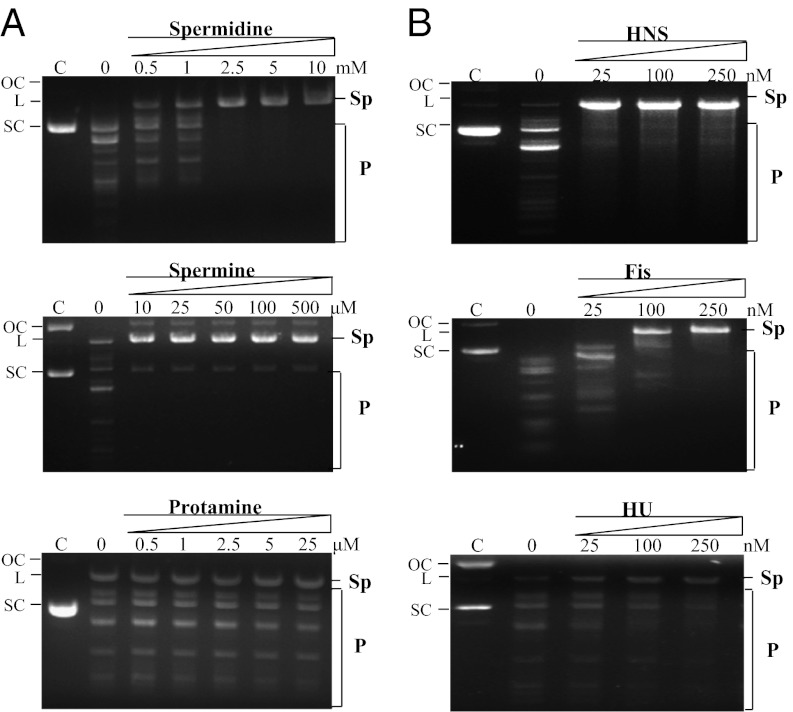

The dsDNA breaks catalyzed by REases could be lethal to the host genome if they are not controlled (26). The host cell harboring promiscuous R.KpnI and site-specific M.KpnI (14) needs to protect its genome not only at the canonical sites but at the noncanonical sites. In case of type I R-M systems, it is established that the resident chromosome is recognized as self rather than foreign even in the absence of modification, a phenomenon known as “restriction alleviation” (27, 28). However, similar mechanisms are not known for the type II R-M systems. Genomes of γ-proteobacteria are complexed with polyamines and various nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs), all of which bind in a nonspecific fashion to cause bending, wrapping, bridging, and/or coating of DNA, which, in turn, could affect various DNA transaction processes (29–31). To determine the mechanisms that operate to discriminate self vs. nonself at the noncanonical sequences, R.KpnI DNA cleavage activity was compared on “naked” DNA and DNA coated with polyamines or NAPs.

When plasmid DNA coated with varying concentrations of polyamines was used as substrate, promiscuous activity was suppressed with increasing concentrations of these ligands (Fig. 5A). In the absence of polyamines, the enzyme exhibited robust promiscuous activity. At 2.5-mM and 0.01-mM concentrations of spermidine and spermine, respectively, the promiscuous activity was undetectable. This correlates well with the intracellular concentrations of spermidine (6.3 mM) and spermine (<1 mM) (32). However, at very high concentrations of polyamines, both canonical and noncanonical sites were refractory to the enzyme-mediated cleavage (Fig. S3). Similarly, the DNA coated with the NAPs (i.e., HU, HNS, Fis) regulated the promiscuous activity to varying degrees (Fig. 5B). Suppression of promiscuous activity was most pronounced in the presence of HNS, followed by that of Fis and HU.

Fig. 5.

Suppression of promiscuous activity of R.KpnI by polyamines and NAPs. Plasmid DNA cleavage activity of R.KpnI was assayed in the presence of different concentrations of polyamines, namely, spermidine and spermine or NAPs (i.e., HNS, Fis, HU). Protamine, a small arginine-rich protein was used as a control. Reactions contained 30 nM R.KpnI, and titration was carried out by preincubation of the supercoiled pUC18 DNA (14 nM) in buffer containing 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) or 2 mM Mg2+ on ice with spermidine (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 mM), spermine (10, 25, 50, 100, and 500 μM), or protamine (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, and 25 μM) (A) or NAPs (25, 100, and 250 nM) (B). The reactions were initiated by addition of the enzyme and incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. Lane C is substrate DNA with no enzyme. Lane 0 shows the DNA cleavage reaction in the absence of polyamines or NAPs. Sp and P indicate specific and promiscuous DNA cleavage products, respectively. SC, L, and OC indicate the positions of the supercoiled, linear, and open circular forms of the plasmid, respectively.

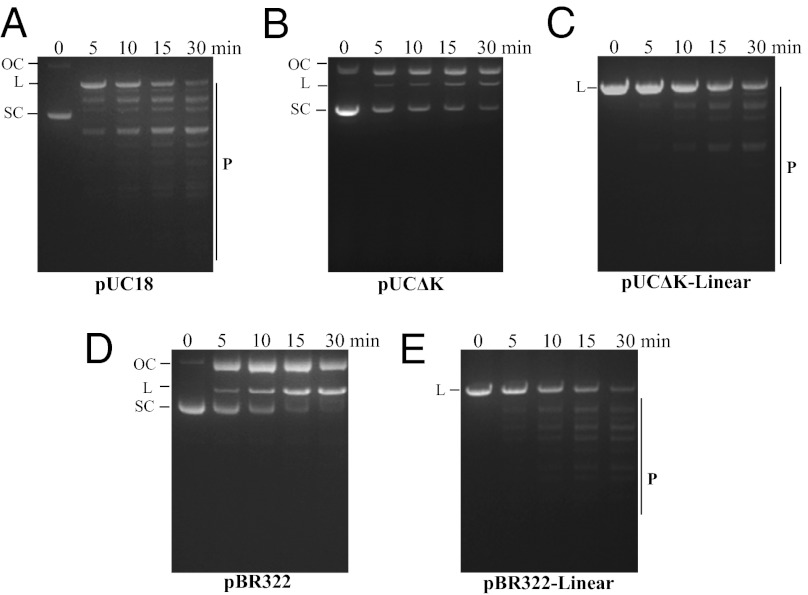

Next, we investigated additional mechanisms that could operate to discriminate self vs. nonself at the noncanonical sequences. Generally, REases recognize the foreign DNA and cleave target sites in it in a processive manner (33, 34). In the case of R.KpnI, a plasmid containing a single recognition site was restricted efficiently at both the canonical and noncanonical sites compared with the plasmid devoid of the canonical site (Fig. 6 A and B). The enhancement of cleavage at noncanonical sites by the presence of a canonical site could occur for two reasons. The enzyme may use a canonical site for initial recognition of foreign genome, which is then followed by cleavage at promiscuous sites. Alternatively, because of the presence of a canonical site, the enzyme could rapidly convert the supercoiled substrate into a linear form that can now be acted on even at noncanonical sites. In other words, the enzyme may discriminate sequences through their topological status. To verify these possibilities, the efficiency of promiscuous DNA cleavage was compared with supercoiled and linearized plasmid substrates devoid of canonical sites. The linear DNA served as an efficient substrate compared with the supercoiled DNA (Fig. 6 B–E), indicating that the R.KpnI could discriminate between the self and nonself at noncanonical sites through their topological status.

Fig. 6.

Effect of canonical recognition sequence on the promiscuous activity of R.KpnI. Plasmids (14 nM) with (pUC18) or without (pUCΔK or pBR322) the KpnI recognition sequence were incubated with the enzyme (30 nM) on ice for 10 min. The reactions were then initiated by adding 2 mM Mg2+ to the plasmid enzyme mixture. The reactions were stopped at the indicated time points by adding a stop dye containing 10 mM EDTA. (A) pUC18 DNA containing a single KpnI recognition sequence. (B) pUCΔK DNA (pUC18 plasmid lacking the KpnI site). (C) Linearized pUCΔK DNA. (D) pBR322 DNA. (E) Linearized pBR322 DNA. P indicates promiscuous DNA cleavage products. SC, L, and OC indicate the positions of the supercoiled, linear, and open circular forms of the plasmid, respectively.

Discussion

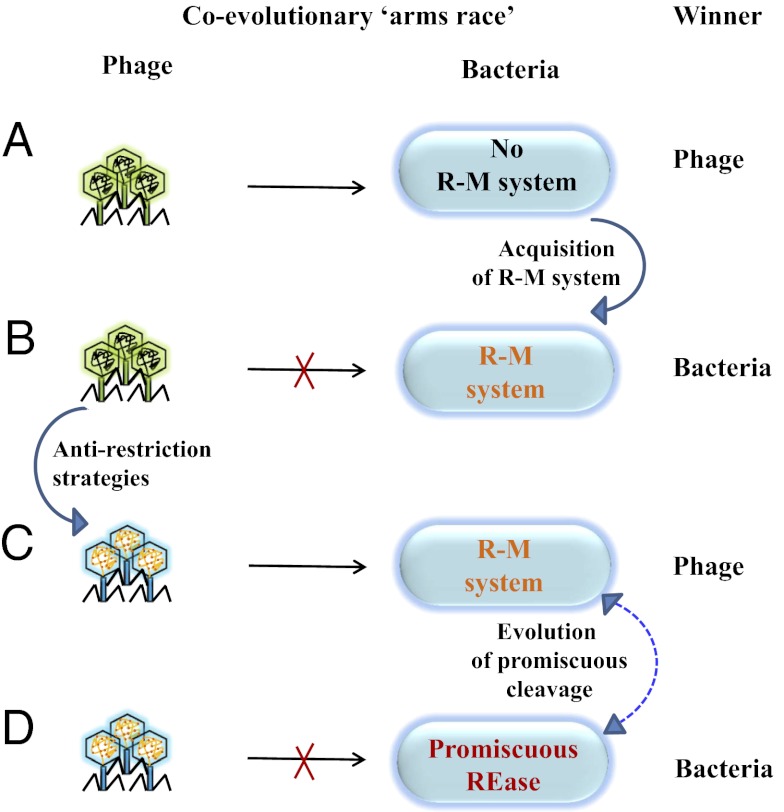

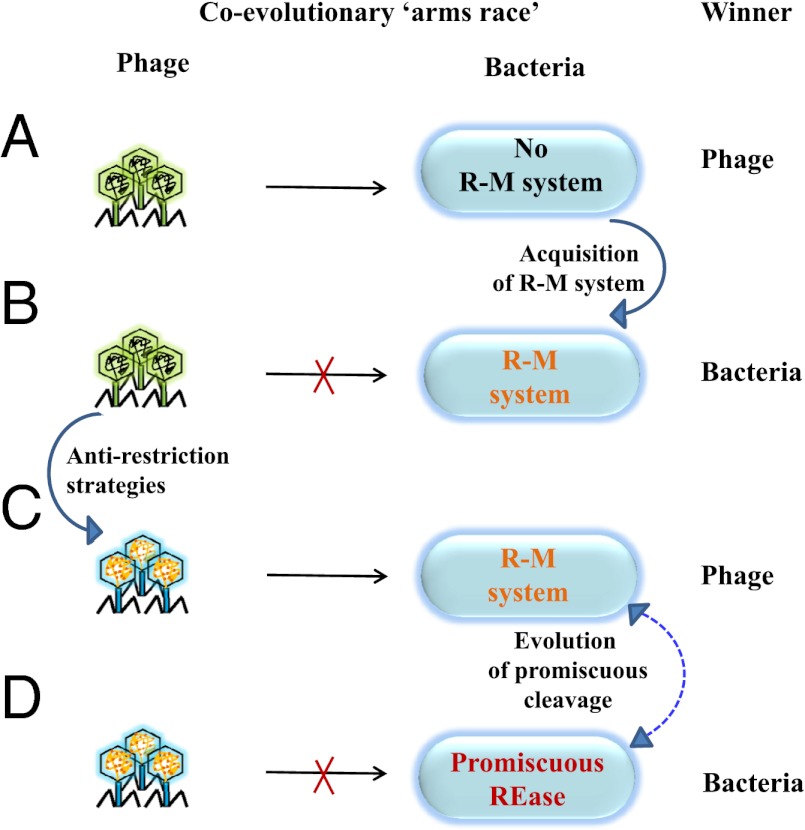

REases are the genomes’ sentinels in bacteria to counter the threat of foreign DNA. Invading genomes evade restriction by using a multitude of antirestriction strategies to increase their fitness (10, 20, 35). Bacteria counteract these antirestriction strategies by acquiring additional R-M systems with distinct recognition specificities (36). The continuous selection for the fitness advantage leads to a coevolutionary arms race between the phages and their hosts (10, 20). The restriction and antirestriction genes are thus under a constant evolutionary pressure to tinker with their functionality for providing a better fitness advantage to respective genomes where they reside. Studies described here reveal a hitherto undescribed paradigm to counter the antirestriction strategies of the invading genomes.

Although the specific cleavage by a REase allows bacteria to adapt to new environments, its maintenance appears to be selected against in a constantly evolving environment enriched with phages (37). The high specificity has a caveat in inducing adaptation among phages to evade restriction either by (i) decreasing the palindromic sequences (38–40) or (ii) modification (methylation or glucosylation) of the phage DNA (10, 20). The two strategies decrease the effective number of REase recognition sites in the genome of a phage (22, 38–43). The presence of multiple R-M systems, adaptive immunity by interference, and selective silencing of xenogeneic sequences are some of the mechanisms that bacteria use to enhance protection against the invading foreign DNA (29, 44, 45). Although these bacteriophage resistance mechanisms offer protection, they operate either with a low frequency or with lower adaptability (44, 46). The ability of an enzyme to cleave foreign DNA with broader specificity appears to be an improved protection mechanism under these circumstances (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Coevolutionary arms race between the phages and their hosts results in the utilization of promiscuous activity as a defense strategy. Phage as the winner indicates successful infection of the host. Bacteria as the winner indicate efficient restriction of phage DNA. (A) In the absence of an R-M system, the phage emerges as the winner because of its ability to infect the bacteria. (B) Host adapts by acquiring an R-M system that can now restrict the invading DNA elements. (C) This, in turn, leads to the development of antirestriction strategies in the phages by (i) acquisition of DNA modification systems (e.g., methylation, glucosylation) or (ii) avoiding palindromic DNA sequences. (D) However, a promiscuous REase would target even those phages that are equipped with antirestriction mechanisms, thus conferring a survival advantage. The promiscuous cleavage characteristics may be acquired by the site-specific REase or retained during the evolution. Irrespective of the directionality, possessing promiscuous activity is advantageous to the bacteria in better restricting the invading genome elements.

One of the important attributes of DNA transaction processes is the ability to distinguish between different DNA substrates, for example, replicated vs. nonreplicated DNA or host vs. foreign DNA. For this, the cell has to ensure that the DNA molecules are chemically different as achieved by host DNA methylation. When a phage attacks an R-M proficient cell encoding a promiscuous REase and a site-specific MTase, as in the case of the KpnI R-M system, the host genome and foreign DNA molecules have to be distinguished by the REase at the noncanonical sites. The bacterial genome is coated by NAPs and polyamines, and is thus recognized by the REase as self (47). Because the foreign DNA is likely to be in an uncondensed form (28, 48), it renders itself the perfect target for the dsDNA cleavage at canonical as well as noncanonical sequences. However, the efficiency of restriction at noncanonical sites would depend on the kinetics of the association of invading DNA with polyamines and NAPs. Apart from what is described here for R.KpnI, the ability to discriminate spermine-coated host genome vs. naked foreign DNA is also reported for the type I enzyme EcoKI (49). Host genome protection from R.KpnI seems to be distinct in using both the DNA topology and the nucleoid organization to discriminate between the host vs. xenogeneic genomes at noncanonical sequences.

Despite all these protection mechanisms, accidental DNA scissions, if inflicted by the REase, could be rescued by DNA ligase or homologous recombination-mediated repair pathways. These repair mechanisms are known to rescue cells from lethality caused by type I and type II REases (50–53). Hence, it appears that the cell’s ability to discriminate between its own DNA and foreign DNA on the basis of (i) canonical methylation, (ii) nucleoid organization, and (iii) differences in DNA topology and repair mechanisms protect the cell from detrimental consequences of accidental host genome destruction and provide a fitness advantage.

Recent studies carried out with >200 REases have revealed that a majority of the REases in the group exhibit relaxed substrate specificity (54, 55). Thus, it appears that the catalytic promiscuous activity is an intrinsic property of these enzymes. Notably, a single point mutation could convert the promiscuous R.KpnI to an HF REase (17). Taking a cue from this work, 27 promiscuous REases were converted into HF enzymes by point mutations (6). It is likely that many REases retain an inherent flexibility in sequence recognition during the course of evolution. Thus, the current paradigm of high sequence specificity of REases for their physiological purpose may need to be revisited. It is unlikely that every type II enzyme would exhibit characteristics similar to R.KpnI, given their vast diversity. Nevertheless, promiscuity could be a widespread phenomenon, because it may be a kind of natural law favoring flexibility.

Endonuclease II of T4 coliphage uses relaxed specificity to initiate host DNA degradation, whereas the phage genome is protected because of hydroxymethylated cytosines (56). Thus, the utilization of promiscuous activity to target the opponent genome exists in phages. Now, it is apparent that a similar strategy could have been developed by bacteria to counteract the antirestriction mechanisms of the phages. The counterstrategies that may potentially be developed by the phages against the REase promiscuity, if any, need further investigation.

The high degree of promiscuity exhibited by R.KpnI hints at the evolutionary link between the nonspecific and highly sequence-specific endonucleases. Specific endonucleases have either evolved into nonspecific endonucleases or vice versa because of certain selection forces. In the case of R.KpnI, although it is possible that the HF variants of the enzyme could exist in the natural habitat,the organism appears to prefer promiscuous activity. Moreover, the cofactor Mg2+ that activates promiscuous activity is used by the enzyme in vivo over other metal ions (Ca2+ or Zn2+) that induce fidelity in DNA cleavage. We surmise that promiscuous activity of R.KpnI has either been retained or has evolved to counteract the attack by foreign genomes.

The reason for the occurrence of catalytically proficient, noncanonical DNA cleavage by REases under altered conditions has been enigmatic. Our study answers an important but unaddressed question as to why a given REase retains catalytic promiscuous activity. The retention of the promiscuous cleavage characteristics of a type II REase that is normally expected to possess exquisite sequence specificity provides a selective advantage for the bacterial genome in the coevolutionary arms race between phages and bacteria.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, Substrates, and Enzymes.

The strains and genotypes of bacteria and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. K. pneumoniae strain OK8 (American Type Culture Collection 4970 strain) containing a KpnI R-M system was used for endonuclease assays with cell extracts. E. coli strains DH10B and BL26 (DE3) were used for cloning and overexpression, respectively. R.KpnI was expressed in E. coli BL26 cells in the presence of pACMK (plasmid-expressing KpnI MTase from its native promoter). All inductions were done with 50 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and the expression of R.KpnI and its mutants in various in vivo experiments was confirmed by Western blot analysis. The kpnI R-M system with its own promoter elements was cloned in pACYC184 at HindIII and BamHI sites (pACR-M) with an additional support plasmid expressing KpnI MTase (pUCMK). The positive clones were cured for the pUCMK plasmid by growing the culture in the absence of ampicillin. The cells cured for pUCMK express both MTase and REase from their respective endogenous promoters (KpnI R-M). R.KpnI expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis using polyclonal antibodies. The clones with REase expression comparable to its level in K. pneumoniae strain OK8 were used for the in vivo assays.

Oligonucleotides (Sigma–Aldrich) used for DNA cleavage assays (Table S2) were purified on 8 M urea – 18% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel. The purified oligonucleotides were end-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol). R.KpnI and its mutants were purified using the method described previously (25). E. coli HNS was purified with a nickel-nitriloacetic acid-agarose column (Qiagen). E. coli Fis protein was purified as described (57). E. coli HU protein was purified as described (58). The purity of the proteins was assessed by SDS/PAGE.

Phage Restriction and Growth Studies.

Restriction activity in vivo was estimated by the ability of cells with an R-M system to restrict plaque formation by P1vir and λvir bacteriophages. P1vir and λvir phage strains possess 25 and 2 sites for KpnI (GGTACC), respectively. The media used for these experiments contained selective antibiotics. Modification of the phage genome was carried out by preparing the phage lysates on E. coli BL26 strain overexpressing KpnI MTase (pUCMK). M.KpnI does not exhibit promiscuous behavior and methylates in a site-specific manner (14). The modification status of the phage genomes was confirmed by resistance to site-specific cleavage by KpnI REase both in vitro and in vivo. Phage plaque assays were carried out using the top agar overlay technique. Briefly, an overnight culture of E. coli BL26 MK+ cells harboring vector, the WT, or the HF variant was diluted 100-fold and grown to midexponential phase at 37 °C with aeration in LB broth. Phages were appropriately diluted (10−3 to 10−7 serial dilutions) and mixed with 100 μL of the fresh culture. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, the phage–bacteria complex was mixed with 3 mL of LB top agar and poured on an agar plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 8–12 h, plaques were counted.

For growth studies, overnight cultures of E. coli BL26 MK+ cells harboring vector, the WT, or the HF variant were diluted (1:500) into fresh LB medium and grown. In the case of growth studies in the presence of phages, ∼106 plaque forming units (PFU) were inoculated along with the bacterial cultures. Growth was measured by taking absorbance at 600 nm.

DNA Condensation and in Vitro DNA Cleavage Activity.

DNA condensation was carried out using different concentrations of polyamines (spermidine and spermine) and protamine (a small arginine-rich protein was used as a control) in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4). Stock solutions of spermidine, spermine, and protamine (Sigma–Aldrich) were added to DNA in the reaction buffer and incubated on ice for 15 min before adding R.KpnI and 2 mM Mg2+. Activity on the modified DNA was analyzed by incubation for 1 h at 37 °C. DNA cleavage assays were carried out using 14 nM pUC18, pUCΔK (pUC18 lacking KpnI site), and pBR322 as described (14). For pUC18, the enzyme/canonical site ratio was 2.1:1, and for all three plasmids used, the enzyme/noncanonical site ratio was lower than 1. Linearized plasmid substrates of pUCΔK and pBR322 were prepared by digesting with R.BamHI. For DNA cleavage assays with cell extracts, K. pneumoniae strain OK8 containing the KpnI R-M system was grown in 50 mL of LB to an OD600 of 0.6. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 3 mL of extraction buffer [10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol], and disrupted by sonication. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and dilutions of the supernatant (1:1,000 to 1:10) prepared with extraction buffer were used for the DNA cleavage assays as described (14).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. N. Rao and S. Mahadevan for E. coli HU- and HNS-overexpressing clones, P. Uma Maheswari for technical assistance, and S. Ghosh and S. Karambelkar for purified E. coli HU and Fis proteins, respectively. New England Biolabs provided K. pneumoniae strain OK8. We thank T. A. Bickle, K. P. Gopinathan, D. N. Rao, U. Varshney, and members of the V.N. laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. K.V. is the recipient of a Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Government of India. V.N. is the recipient of a J. C. Bose Fellowship from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Author Summary on page 7608 (volume 109, number 20).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1119226109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Khersonsky O, Roodveldt C, Tawfik DS. Enzyme promiscuity: Evolutionary and mechanistic aspects. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen RA. Enzyme recruitment in evolution of new function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1976;30:409–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.30.100176.002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien PJ, Herschlag D. Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities. Chem Biol. 1999;6:R91–R105. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aharoni A, et al. The ‘evolvability’ of promiscuous protein functions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:73–76. doi: 10.1038/ng1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshikuni Y, Ferrin TE, Keasling JD. Designed divergent evolution of enzyme function. Nature. 2006;440:1078–1082. doi: 10.1038/nature04607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu Z, et al. 2009. Patent US 2009/0029376 A1.

- 7.Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS. Enzyme promiscuity: A mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:471–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pingoud A, Fuxreiter M, Pingoud V, Wende W. Type II restriction endonucleases: Structure and mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:685–707. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arber W, Linn S. DNA modification and restriction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1969;38:467–500. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.38.070169.002343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tock MR, Dryden DTF. The biology of restriction and anti-restriction. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowan JA, editor. Role of Metal Ions in Promoting DNA Binding and Cleavage by restriction Endonucleases. Berlin: Springer; 2004. pp. 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thielking V, Alves J, Fliess A, Maass G, Pingoud A. Accuracy of the EcoRI restriction endonuclease: Binding and cleavage studies with oligodeoxynucleotide substrates containing degenerate recognition sequences. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4682–4691. doi: 10.1021/bi00471a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sapienza PJ, Dela Torre CA, McCoy WH, 4th, Jana SV, Jen-Jacobson L. Thermodynamic and kinetic basis for the relaxed DNA sequence specificity of “promiscuous” mutant EcoRI endonucleases. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:307–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandrashekaran S, Saravanan M, Radha DR, Nagaraja V. Ca(2+)-mediated site-specific DNA cleavage and suppression of promiscuous activity of KpnI restriction endonuclease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49736–49740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saravanan M, Vasu K, Kanakaraj R, Rao DN, Nagaraja V. R.KpnI, an HNH superfamily REase, exhibits differential discrimination at non-canonical sequences in the presence of Ca2+ and Mg2+ Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2777–2786. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowan JA. Structural and catalytic chemistry of magnesium-dependent enzymes. Biometals. 2002;15:225–235. doi: 10.1023/a:1016022730880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saravanan M, Vasu K, Nagaraja V. Evolution of sequence specificity in a restriction endonuclease by a point mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10344–10347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804974105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alatossava T, Jütte H, Kuhn A, Kellenberger E. Manipulation of intracellular magnesium content in polymyxin B nonapeptide-sensitized Escherichia coli by ionophore A23187. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:413–419. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.413-419.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arber W. Host specificity of DNA produced by Escherichia coli V. The role of methionine in the production of host specificity. J Mol Biol. 1965;11:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bickle TA, Krüger DH. Biology of DNA restriction. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:434–450. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.434-450.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krüger DH, Barcak GJ, Smith HO. Abolition of DNA recognition site resistance to the restriction endonuclease EcoRII. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1988;47:K1–K5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson GG, Murray NE. Restriction and modification systems. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:585–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chatterjee DK, Hammond AW, Blakesley RW, Adams SM, Gerard GF. Genetic organization of the KpnI restriction–modification system. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6505–6509. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.23.6505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawley DK, McClure WR. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:2237–2255. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.8.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandrashekaran S, Babu P, Nagaraja V. Characterization of DNA binding activities of over-expressed kpnI restriction endonuclease and modification methylase. J Biosci. 1999;24:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asakura Y, Kobayashi I. From damaged genome to cell surface: Transcriptome changes during bacterial cell death triggered by loss of a restriction-modification gene complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3021–3031. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keatch SA, Leonard PG, Ladbury JE, Dryden DTF. StpA protein from Escherichia coli condenses supercoiled DNA in preference to linear DNA and protects it from digestion by DNase I and EcoKI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6540–6546. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makovets S, Powell LM, Titheradge AJ, Blakely GW, Murray NE. Is modification sufficient to protect a bacterial chromosome from a resident restriction endonuclease? Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:135–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dillon SC, Dorman CJ. Bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins, nucleoid structure and gene expression. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:185–195. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabor CW, Tabor H. Polyamines. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:749–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pingoud A, et al. Effect of polyamines and basic proteins on cleavage of DNA by restriction endonucleases. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5697–5703. doi: 10.1021/bi00319a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabor CW, Tabor H. 1,4-Diaminobutane (putrescine), spermidine, and spermine. Annu Rev Biochem. 1976;45:285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.45.070176.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeltsch A, Urbanke C. In: Sliding or hopping? How restriction enzymes find their way on DNA restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology. Pingoud AM, editor. Vol 14. Springer, Berlin; 2004. pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gowers DM, Halford SE. Protein motion from non-specific to specific DNA by three-dimensional routes aided by supercoiling. EMBO J. 2003;22:1410–1418. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bickle TA. Restricting restriction. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:3–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng Y, et al. A unique family of Mrr-like modification-dependent restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5527–5534. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chinen A, Naito Y, Handa N, Kobayashi I. Evolution of sequence recognition by restriction-modification enzymes: Selective pressure for specificity decrease. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1610–1619. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karlin S, Mrázek J, Campbell AM. Compositional biases of bacterial genomes and evolutionary implications. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3899–3913. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3899-3913.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blaisdell BE, Campbell AM, Karlin S. Similarities and dissimilarities of phage genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5854–5859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelfand MS, Koonin EV. Avoidance of palindromic words in bacterial and archaeal genomes: A close connection with restriction enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2430–2439. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.12.2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharp PM. Molecular evolution of bacteriophages: Evidence of selection against the recognition sites of host restriction enzymes. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:75–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warren RA. Modified bases in bacteriophage DNAs. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:137–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swinton D, et al. Purification and characterization of the unusual deoxynucleoside, alpha-N-(9-beta-D-2′-deoxyribofuranosylpurin-6-yl)glycinamide, specified by the phage Mu modification function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:7400–7404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brouns SJ, et al. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008;321:960–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1159689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cardinale CJ, et al. Termination factor Rho and its cofactors NusA and NusG silence foreign DNA in E. coli. Science. 2008;320:935–938. doi: 10.1126/science.1152763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horvath P, et al. Diversity, activity, and evolution of CRISPR loci in Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1401–1412. doi: 10.1128/JB.01415-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorman CJ. Nucleoid-associated proteins and bacterial physiology. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2009;67:47–64. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)01002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luijsterburg MS, White MF, van Driel R, Dame RT. The major architects of chromatin: Architectural proteins in bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:393–418. doi: 10.1080/10409230802528488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keatch SA, Su TJ, Dryden DTF. Alleviation of restriction by DNA condensation and non-specific DNA binding ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5841–5850. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cromie GA, Leach DR. Recombinational repair of chromosomal DNA double-strand breaks generated by a restriction endonuclease. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:873–883. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heitman J, Zinder ND, Model P. Repair of the Escherichia coli chromosome after in vivo scission by the EcoRI endonuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2281–2285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith MD, Longo M, Gerard GF, Chatterjee DK. Cloning and characterization of genes for the PvuI restriction and modification system. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5743–5747. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.21.5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tímár E, Venetianer P, Kiss A. In vivo DNA protection by relaxed-specificity SinI DNA methyltransferase variants. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:8003–8008. doi: 10.1128/JB.00754-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei H, Therrien C, Blanchard A, Guan S, Zhu Z. The Fidelity Index provides a systematic quantitation of star activity of DNA restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray IA, Stickel SK, Roberts RJ. Sequence-specific cleavage of RNA by Type II restriction enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:8257–8268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lagerbäck P, Andersson E, Malmberg C, Carlson K. Bacteriophage T4 endonuclease II, a promiscuous GIY-YIG nuclease, binds as a tetramer to two DNA substrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6174–6183. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osuna R, Finkel SE, Johnson RC. Identification of two functional regions in Fis: The N-terminus is required to promote Hin-mediated DNA inversion but not lambda excision. EMBO J. 1991;10:1593–1603. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joseph N, Sawarkar R, Rao DN. DNA mismatch correction in Haemophilus influenzae: Characterization of MutL, MutH and their interaction. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1561–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]