Abstract

The ability to control fire was a crucial turning point in human evolution, but the question when hominins first developed this ability still remains. Here we show that micromorphological and Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (mFTIR) analyses of intact sediments at the site of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa, provide unambiguous evidence—in the form of burned bone and ashed plant remains—that burning took place in the cave during the early Acheulean occupation, approximately 1.0 Ma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the earliest secure evidence for burning in an archaeological context.

Keywords: micromorphology, cooking hypothesis, Homo erectus

The ability to control fire was a crucial turning point in human evolution, but there is no consensus as to when hominins first developed this ability. According to Richard Wrangham's “cooking hypothesis,” Homo erectus was adapted to a diet of cooked food and therefore was capable of controlling fire (1). Recent phylogenetic studies on nonhuman and human primates based on associated trends in body mass, feeding time, and molar size support the hypothesis of the adoption of a cooked diet at least as early as the first appearance of H. erectus approximately 1.9 Ma (2). However, to date, the evidence for controlled use of fire in association with H. erectus is scant and inconclusive, as pointed out in a recent review of the archaeological record by Roebroeks and Villa (3). Unequivocal evidence for the habitual use of fire in early hominin sites, such as that reported for Qesem Cave (4), is so far found in sites dated after 0.4 Ma, thus associating the earliest control of fire primarily with early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals (3).

Through the application of micromorphological analysis and Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (mFTIR) of intact sediments and examination of associated archaeological finds—fauna, lithics, and macrobotanical remains—we provide unambiguous evidence in the form of burned bone and ashed plant remains that burning events took place in Wonderwerk Cave during the early Acheulean occupation, approximately 1.0 Ma. To date, to the best of our knowledge, this is the earliest secure evidence for burning in an archaeological context.

Previous Research on Early Evidence of Fire

Claims for early traces of fire have been made for sites in Africa, Asia, and Europe (5). In East Africa, sites that have produced evidence of fire include Gadeb 8E, Koobi Fora FxJj 20 East, and Chesowanja GnJi 1/6E. At Chesowanja, dated to more than 1.42 ± 0.07 Ma based on K-Ar dating of an overlying basalt, 40 pieces of discolored clay aggregates were found intermingled with Developed Oldowan lithics and fauna (6). Magnetic susceptibility analysis of the rubefied clay aggregates indicates that they were burned. At Gadeb 8e, magnetic properties of cobbles of welded tuff indicate that they were also burned (7), and at Koobi Fora FxJj 20—dated to 1.5 Ma—similarly discolored sediment patches were identified as having been burned based on thermoluminescence properties (8, 9). Comparable analyses have been made on sites in the Middle Awash (10). At Swartkrans (South Africa), burned bones were identified from member 3, dated to ca. 1.0 to 1.5 Ma, based on histological characteristics and chemical identification of char (11–13). However, at Swartkrans, the burned bones appear to be in secondary context in the fill of a gully (11). Some of the most intensive research on early use of fire has focused on the site of Gesher Benot Ya'akov in the Jordan Valley (Israel), dated to between 0.7 and 0.8 Ma, where pot-lid fractures, characteristic rounded concave scars produced by heat-induced removal of planoconvex flakes, have been used to identify burned microdebitage (14). Thermoluminescence analysis supports the identification of burned microdebitage, and its spatial distribution, together with the presence of charred wood, seeds, and grains led to the identification of “phantom hearths” (5, 15, 16). Nevertheless, the evidence and acceptance for controlled use of fire at any of the Acheulean sites noted earlier remains controversial. The controversies stem from the fact that these are open-air sites and it is not possible to completely exclude the action of wildfires (3). Moreover, in none of the Acheulean contexts reviewed earlier has research included microstratigraphic analysis of the deposits that encase the burned objects. There is no evidence of, nor were attempts made to look for, calcareous wood ash (i.e., ashed plant tissues and oxalate pseudomorphs) as reported in Qesem Cave (4).

Interestingly, at Zhoukoudian in China, microstratigraphic analysis demonstrated that features as old as 0.6 Ma originally considered evidence of in situ combustion (e.g., layer 10) or wood ash residues (e.g., layer 4) are actually the result of water-deposited organic-rich sediment and colluvial reworking of loess, respectively (17). Although Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis supports the presence of burned bones associated with burned flint at Zhoukoudian (18), these remains are not directly associated with in situ anthropogenic combustion features. Thus, any reasonable statement about their unambiguous association to hominin behavior remains inconclusive (17, 18).

The use of high-resolution microscopic analysis of intact sediments has been used extensively in the Middle Stone Age of Africa and the Middle Paleolithic of the Middle East and Europe (cited in refs. 19, 20). Numerous microscopic studies of combustion features clearly reveal information not readily obtainable with other analytical techniques, including fuel composition, internal organization of the feature, and combustion conditions (19, 20). Such studies illustrate the range of ways that Neanderthals and early modern humans were associated with fire in their occupation sites (21). Historically, with the exception of Zhoukoudian, research that used microstratigraphic analyses of contextualized intact sediments have been absent in the study of early hominin use of fire.

Wonderwerk Cave

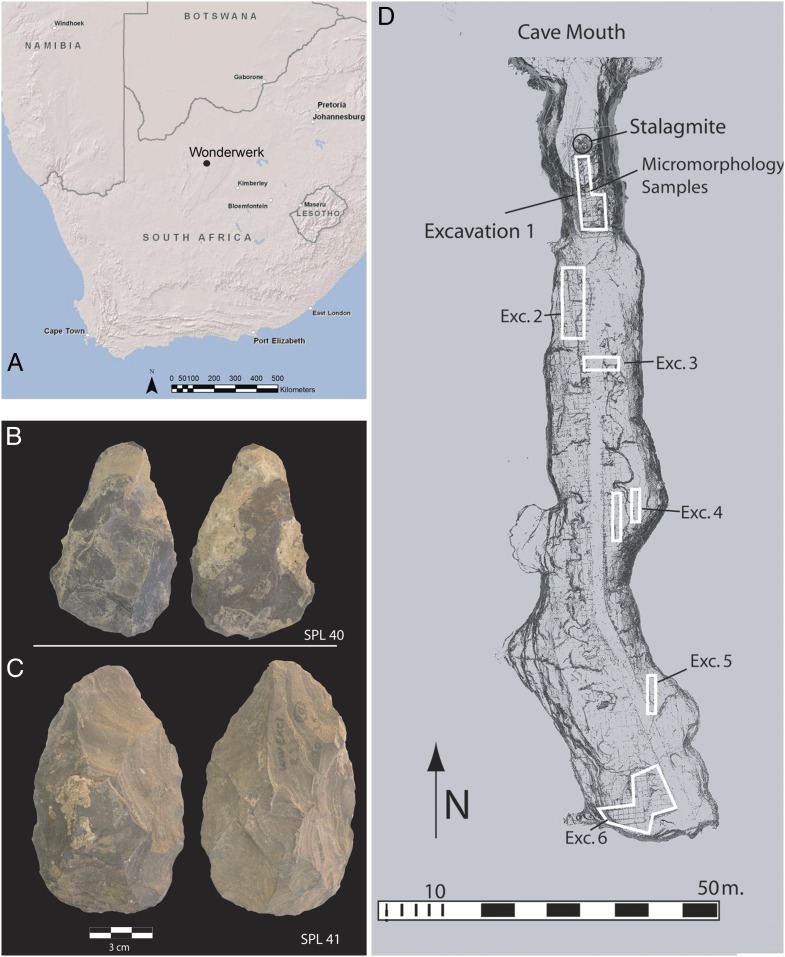

Wonderwerk Cave (Fig. 1) is an approximately 140-m-long phreatic tube that formed in Precambrian dolostones of the Kuruman Hills (Northern Cape province, South Africa). Beginning in the 1970s and ending in the 1990s, extensive archaeological excavations were carried out by P. B. Beaumont in seven different areas within the cave (Fig. 1D). The longest Earlier Stone Age (ESA) sequence, approximately 2 m deep, is found in excavation 1, currently located approximately 30 m in from the cave mouth, immediately behind a large, active stalagmite which developed during the past 35,000 y (22, 23).

Fig. 1.

(A) Map showing the location of Wonderwerk Cave. (B–C) Handaxes characteristic of the Acheulean of stratum 10, excavation 1, Wonderwerk Cave. (D) Plan of Wonderwerk Cave generated by laser scanning shows the location of excavation areas discussed in this study (courtesy of H. Rüther, Zamani project).

Since 2004, our team has renewed fieldwork, performed chronometric dating. and reanalyzed the archaeological record of the site (24, 25). Details on the archaeological, lithological, and chronological stratigraphy of excavation 1 are given in SI Text and illustrated in Figs. S1–S4. The archaeological sequence begins with a small tool industry attributed to the Oldowan in basal stratum 12, which is overlain by an Acheulean sequence. This sequence shows developments from rare protobifaces (stratum 11) through bifaces with noninvasive retouch in stratum 10 (Fig. 1 B and C), to highly refined biface production beginning in stratum 9 (detailed in SI Text and Fig. S2). The evidence for fire presented in this study comes from stratum 10. Beaumont's excavation of this stratum covered 48 square yards (Fig. S1), and yielded a low density of lithic artifacts comprising only seven bifaces (Fig. 1 B and C and Fig. S3 A–D), 36 flakes, 15 cores, and 23 slabs of banded ironstone showing flake removals that were classified as “modified slabs.”

Results

Site Formation and in Situ Evidence of Fire in ESA at Wonderwerk Cave.

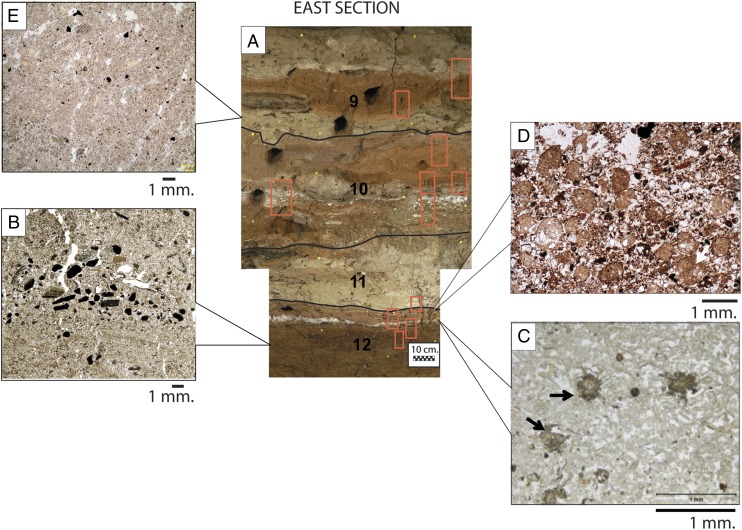

Microstratigraphic investigation combining the use of sediment micromorphology and mFTIR was conducted to investigate site formation processes and human activities in excavation 1 (Fig. 2). Micromorphological analysis indicates that the lithological sequence in excavation 1 began with an archaeologically sterile phreatic sediment. This is overlain by the earliest archaeological occupation (stratum 12) characterized by low-energy water deposition of sand and fine gravel, probably caused by sheet flow (Fig. 2B). From the top of stratum 12, the depositional processes involved the accumulation of aeolian material composed of rounded aggregates of silty clay (Fig. 2D) that formed in drying ponds outside the cave, as well as fine sand (Fig. 2E); in some of the strata, the aeolian aggregates appear reworked by gravity or trampling. The aeolian deposition is interspersed with episodes of cave roof/wall collapse and successive diagenesis of dolostone or flowstone that produced grayish-white phosphatized layers, rich in dark oxide nodules and degraded rock fragments (Fig. 2C). These white layers were at first erroneously interpreted as remains of combustion features (23).

Fig. 2.

(A) Photograph of the east section in excavation 1 with boundaries between archaeological strata 12 and 9. Numbered boxes indicate location of intact block sampled for microstratigraphic analysis. (Scale bar: 10 cm) (B) Representative micrograph of low-energy, water-bedded silt, sand, and 0.5-cm-thick gravel (lag) from stratum 12. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (C) Micrograph of microfacies from white layer close to top of stratum 12 composed of diagenetically altered dolostone and flowstone, with nodules of montgomeryite (arrows). (D) Micrograph of reddish-brown, wind-blown silty clay aggregates that comprise several lithological units starting from the top of stratum 12. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (E) Representative micrograph of wind-blown, fine sand mixed with millimeter-sized bone fragments from tan lithological units in strata 11, 10, and 9. (Scale bar: 1 mm.)

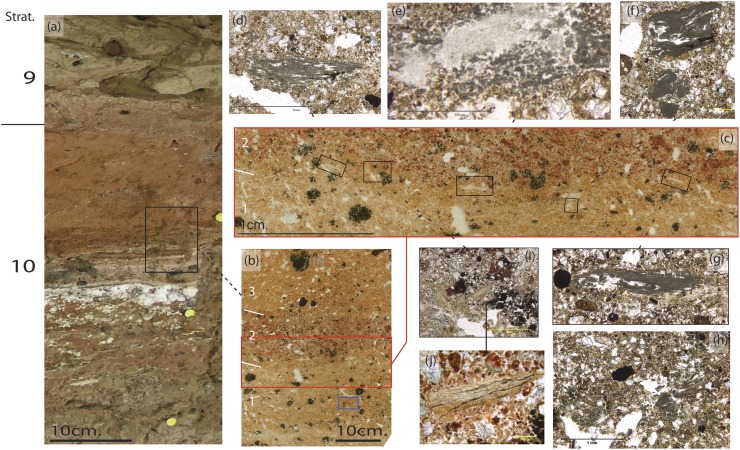

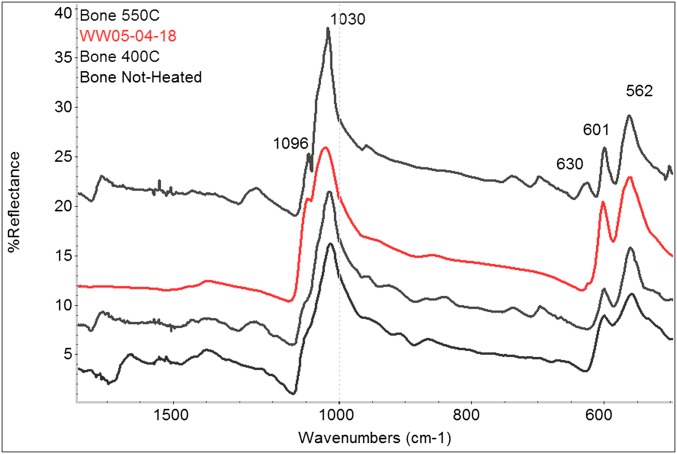

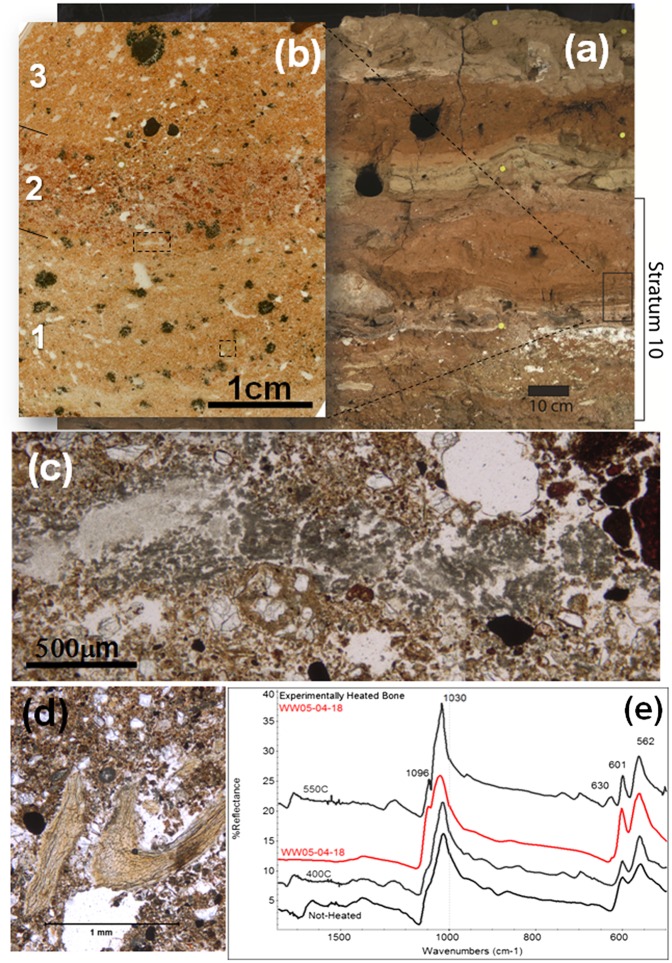

Field and microscopic observations of thin sections revealed that stratum 10 is composed of a complex sequence of lithological centimeter-scale microstratigraphic units (i.e., microfacies) (26). Three of these are illustrated in the thin-section scans shown in Fig. 3. Micromorphological analysis shows that the upper part of the basal microfacies 1 is a clearly defined surface that exhibits abundant remains of ashed plants and minute bone fragments (Fig. 3). As a number of intact blocks of sediment encompassed this part of the stratigraphic sequence, it was possible to document a few surfaces and the evidence for burning over 1 meter along the section (Fig. S5). FTIR microspectroscopy applied directly to thin sections made from these blocks shows that some of the bones lying on these surfaces had been heated to ca. 500 °C (Fig. 4 and Fig. S5). Significantly, the angularity of bone fragments and the exceptional state of preservation of the ashed plant material (Fig. 3 C and D and Fig. S5) indicate that both components were not transported from a distance into the cave by water or wind, but were combusted and accumulated locally. Moreover, micromorphology and mFTIR did not show evidence for remains of guano and/or high-temperature phosphate mineral phases (i.e., berlinite and hydroxylellestadite); these minerals characteristically form during spontaneous combustion of bat guano—a rare event but one documented inside caves (27).

Fig. 3.

(A) Photograph of east profile corresponding to squares R/Q28 showing a detailed view of stratum 10. Box indicates approximate location of thin section (B), exhibiting three microstratigraphic units (microfacies): (1) bottom sandy silt and clay mixed with ashed plant material, dispersed wood ash, and bone fragments; (2) clay aggregates and fragments; and (3) rounded aggregates of sandy silt. Large red rectangular box indicates the location of boundary between microfacies 1 and 2, which is enlarged immediately above in C. Small blue box indicates subsurface location with wood ash pieces dispersed in silty sediment (enlarged in H). (C) Magnification of contact area between microfacies 1 and 2 in thin section shown in B shows characteristic of erosion and successive stabilized surface, on top of which are ashed plant material and bone fragments shown in micrographs (D–J). Boxes mark the location of microphotographs shown in D–G, I, and J (PPL). (Scale bar: 1 cm.). (D) Micrograph of fragments of ashed plant material (PPL). (Scale bars: 1 mm.) (E) Micrographs of lump of calcitic wood ash with typical ash rhombs (oxalate pseudomorphs) and prisms at the contact between microfacies 1 and 2 (PPL). (Scale bar: 500 μm.). (F and G) Micrographs of fragments of ashed plant material (PPL) (Scale bars: 1 mm.) (H) Sediment from microfacies 1, with fragmented ashed plant material and dispersed wood ash rhombs and prisms (oxalate pseudomorphs; PPL). (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (I) Micrograph of contact area between microfacies showing clay aggregates in microfacies 2 and organometallic area (degraded charred material?) and bone fragments resting on the surface of microfacies 1. (Scale bar: 1 mm.). (J) Micrograph of bone fragment. (Scale bar: 100 μm.)

Fig. 4.

Representative mFTIR reflectance spectra (red line) of bone fragments shown in micrographs of Fig. 4 and Fig. S1, and of an unheated and experimentally heated bone processed in the thin section (black lines). Appearance of infrared bands at 1,096 cm−1 and 630 cm−1 are used as heating temperature indicators, showing that the archaeological fragment was heated to more than 400 °C but less than 550 °C.

The ashed plant remains are situated in the middle of archaeological stratum 10, which shows a normal magnetic orientation and is bracketed between two cosmogenic burial ages of 1.27 ± 0.19 Ma and 0.98 ± 0.19 Ma (Fig. S4 and Table S1) (25). The Normal event can therefore be assigned to the Jaramillo subchron (1.07–0.99 Ma), a time range that fits with current understanding of the chronological position of the early Acheulean within the ESA in Southern Africa (28).

Macroscopic Evidence of Fire in Stratum 10 at Wonderwerk Cave.

In a recent publication, based on his field observations during excavation, Beaumont (23) reported macroscopic evidence for burning in the excavation 1 ESA assemblage. Our investigation is based on the study of faunal, lithic, and macrobotanical assemblages from Beaumont's excavation in stratum 10, in concert with the analysis of their sedimentary contexts.

A sample of stratum 10 fauna (total number of identified specimens, 675; includes 80 teeth and/or tooth fragments and 595 complete bones and/or bone splinters) was studied in detail for macroscopic traces of burning, namely surface darkening and calcination. Much of the fauna from this stratum shows discoloration typical of burning as a result of charring and calcination (Fig. 5). Color changes, interpreted as the result of exposure to fire, were identified on 43.7% (total number of identified specimens, 295) of the bones and teeth in this sample (Table S2). Traces of burning were found on faunal samples from excavation spits (arbitrary 5- or 10-cm-deep levels within a stratum) across the entire excavation area and in all depths within stratum 10.

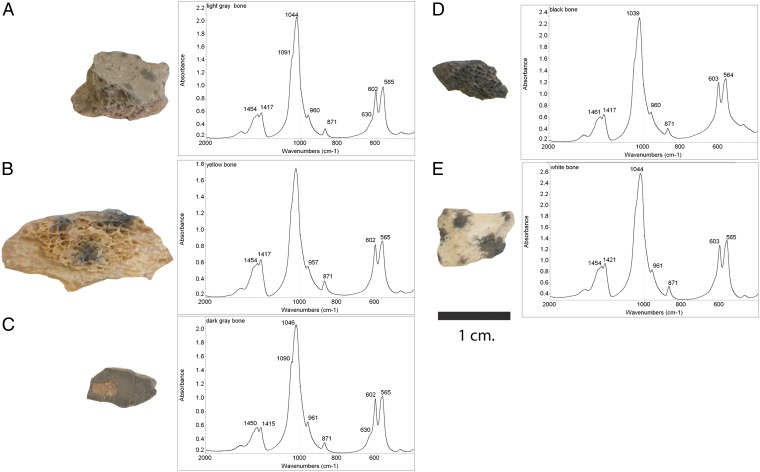

Fig. 5.

Selection of bone fragments recovered close to wood ash identified in thin section (excavation 1, stratum 10, square R28, elevation from top of stratum 10 of 15–20 cm) and their representative FTIR spectra. Gray and black bones (samples A, C, and D) show the presence of IR absorptions at 630 cm−1 and 1,090 cm−1 characteristic of bone mineral heated to more than 400 °C (32). Yellow (B) and white bone (E) fragments show IR spectral pattern characteristic of unheated bone or heated below 400 °C. The circular and irregular opaque nodules are composed of Fe and Mn oxides and a result of diagenetic impregnation.

In square R28, which directly abuts the location with ashed plant material and burned bones on a surface, the frequency of burned bone reached 80% of the sample. FTIR analysis performed on several bone fragments from this square shows that some of the discolored bone fragments (namely black, gray, and white fragments) display FTIR absorption characteristics of bone mineral heated to more than 400 °C (Fig. 5), thus supporting the microstratigraphic observation (Fig. 4 and Fig. S5).

None of the bones analyzed shows IR patterns characteristic of complete calcination, namely the complete removal of the carbonates within the bone carbonate-hydoxylapatite. Thus, none of the specimens analyzed reached temperatures of, or greater than, 700 °C. Sediment adhering to some of the gray bone fragments exhibit FTIR spectral characteristics of clay minerals heated between 400 °C and 700 °C (Fig. S6), again supporting the hypothesis of in situ burning of sediment during the Acheulean in this area of the cave.

Banded ironstone is the main raw material for artifacts found in the Acheulean of excavation 1. Banded ironstone is also found in the assemblage as decimeter-size unworked slabs. These could have entered the cave only as manuports, as the cave is situated in dolostone and there were no site formation processes that could have transported these slabs into the cave (Fig. 2 and Fig. S5). In stratum 10, banded ironstone artifacts and manuports show characteristic pot-lid fractures (Fig. S7A); of 633 spits (arbitrary units of 1 × 1 square yards and 5 cm depth) excavated in stratum 10, 61 produced unworked ironstone with pot-lid fractures. The distribution of the spits that produced ironstone with pot-lid fractures covers the entire excavation area and all depths within stratum 10. Several pot-lid flakes (some refittable to the original slabs; Fig. S8) were found, indicating that fracturing of the ironstone occurred inside the cave. The sizes of pot-lid fractures vary from approximately 1 mm to larger than 4 mm, and are consistent with features produced by us in experimental heating of ironstone at temperatures in excess of 500 °C (Fig. S7B). Although pot-lid fracture can form as a result of agents other than exposure to fire, we have no evidence to support an alternative interpretation for their abundance in the stratum 10 assemblage; pot-lids were rarely observed in surface samples outside the cave.

Discussion and Conclusions

Microstratigraphic investigations of the Acheulean stratum 10 at Wonderwerk Cave show the presence of well preserved ashed plant material and burned bone fragments deposited in situ on discrete surfaces and mixed within sediment in between these surfaces. The good preservation and angularity of the particles suggest that these materials were the products of local combustion episodes that occurred in the proximity of the find spot, which is 30 m in from the present-day entrance.

The significant amounts and extensive distribution of macroscopic burned bone fragments and ironstone manuports with pot-lid fractures, along with evidence of heated sediment, suggest widespread burning events inside the cave. The prevalence of burning throughout the entire thickness of stratum 10 minimizes the likelihood that repeated wildfires were the source of the burning in the cave. Similarly, the absence of guano remains and the lack of characteristic high-temperature phosphates suggest that the burning in stratum 10 was not a result of guano self-ignition episodes. Finally, the possibility of the material being combusted as a result of heat transfer from combustion events occurring in an overlying Holocene layer is highly unlikely because of the interposition of overlying Acheulean deposits.

Thus, our data, although they do not show evidence of constructed combustion features, as listed by Roebroek and Villa as a criterion of controlled burning (3), demonstrate a very close association between hominin occupation and the presence of fire deep inside Wonderwerk Cave during the Early Acheulean. This association strongly suggests that hominins at this site had knowledge of fire 1.0 Ma. This is the most compelling evidence to date offering some support for the cooking hypothesis of Wrangham (1).

Preliminary data suggest that the fuel used in Wonderwerk was composed mainly of “light” plant material such as grasses, brushes, and leaves. Only a small number of identifiable calcified macrobotanical specimens was recovered from stratum 10, including two small fragments of grass culms, two fragments of sedge culm (possibly Eleocharis spp.), and very small fragments of dicot stem or root with diameters that are too small to permit identification (Fig. S9). Interestingly, no large wood charcoal fragments were found in stratum 10. The absence of charred wood could be also a result of diagenetic processes leading to the selective preservation of charred organic materials. Nevertheless, the heating temperatures estimated by FTIR analysis of bones and sediments do not exceed 700 °C (32) and therefore are compatible with fires fueled with leaves and grasses.

Our approach demonstrates that the composition and fabric of combustion deposits are best documented at a microscopic scale, and it offers a partial explanation why traces of early fire have been so difficult to document. It is, in fact, striking that, as opposed to the easily visible combustion features found in Middle Stone Age and Middle Paleolithic cave occupations in Africa, Europe, and the Middle East, the most conclusive evidence for fire was visible only through the use of soil micromorphology. Moreover, the unambiguous identification of burning was possible only with the use of mFTIR directly on thin sections. Additionally, the macroscopic evidence from burned bones and lithic material supports the micromorphological evidence and highlights the need for further research in the investigation of early fire in the archaeological record. We believe microstratigraphic investigations at Wonderwerk cave and other early hominin sites in Asia and South and East Africa will have a significant impact in providing fundamental evidence for the appearance of use of fire and its role in hominin adaptation and evolution.

Materials and Methods

Micromorphology.

Samples were taken as intact blocks and loose samples, oven-dried for several days at 60 °C, and then impregnated with unpromoted polyester resin, diluted with styrene and catalyzed with methyl-ethyl-ketone peroxide. Hardened blocks were trimmed (50 × 75 mm by 10 mm thick) by using a rock saw and then sent to Spectrum Petrographics (Vancouver, WA) for processing into 30-μm-thick petrographic thin sections. The thin sections were examined with binocular and petrographic microscopes in plane-polarized (PPL) and cross-polarized light at magnifications ranging from 20× to 200×. Descriptive nomenclature follows that of Courty et al. (29) and Stoops (30).

FTIR Spectroscopy and Microspectroscopy.

FTIR spectroscopy is a molecular analytical technique well suited to identify heat-related transformation in materials of different nature such as clay minerals (ref. 31 and refs. therein) and bone (32). In particular, because of high temperature, the bone mineral—namely carbonate-hydroxylapatite—undergoes characteristic recrystallization. The recrystallization occurs at approximately 500 °C and above, and is appreciable by FTIR spectroscopy via the sharpening of the ν4PO4 (565–630 cm−1) and ν3PO4 (1,020–1,100 cm−1) bands. The sharpening caused by high temperature results in the appearance of two characteristic peaks at 630 cm−1 and 1,096 cm−1 that are absent in fresh, archaeological, and fossil bone (32). Samples processed in thin section were analyzed by FTIR microspectroscopy by using a Thermo Spectra-Tech Continuum IR microscope attached to a Thermo-Nicolet Nexus 470 IR spectrometer. Spectra of particles with diameter of approximately 150 μm were collected in transmission and total reflectance mode with a Reflectocromat 15× objective between 2,000 cm−1 and 450 cm−1 at 8 cm−1 resolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Fieldwork at Wonderwerk Cave is carried out under permit to M. Chazan from SAHRA and museum analysis under the terms of an agreement with the McGregor Museum. We are grateful to Colin Fortune, Director, and David Morris, Head of Archaeology, and other members of the staff of the McGregor Museum for their assistance. We acknowledge the earlier work carried out at Wonderwerk Cave by Peter Beaumont, which served as the touchstone for this research. We thank Anna Philips for her work on the ironstone heating experiments. This research was funded by grants from the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Wenner Gren Foundation, and National Science Foundation Grants 0917739 and 0551927.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Author Summary on page 7593 (volume 109, number 20).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1117620109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wrangham R. Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. New York: Basic Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organ C, Nunn CL, Machanda Z, Wrangham RW. Phylogenetic rate shifts in feeding time during the evolution of Homo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14555–14559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107806108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roebroeks W, Villa P. On the earliest evidence for habitual use of fire in Europe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5209–5214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018116108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karkanas P, et al. Evidence for habitual use of fire at the end of the Lower Paleolithic: site-formation processes at Qesem Cave, Israel. J Hum Evol. 2007;53:197–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alperson-Afil N, Goren-Inbar N. The Acheulian Site of Gesher Benot Ya'aqov: Ancient Flames and Controlled Use of Fire. Vol 2. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gowlett JAJ, Harris JWK, Walton D, Wood BA. Early archaeological sites, hominid remains, and traces of fire from Chesowanja, Kenya. Nature. 1981;294:125–129. doi: 10.1038/294125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbetti M. Traces of fire in the archaeological record before one million years ago. J Hum Evol. 1986;15:771–781. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellomo R. Methods of determining early hominid behavioral activities associated with the controlled use of fire at FxJj20 Main, Koobi Fora, Kenya. J Hum Evol. 1994;27:173–195. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowlett RM. Fire control by Homo erectus in East Africa and Asia. Acta Anthropologica Sinica Supplement to. 2000;19:198–208. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark JD, Harris JWK. Fire and its roles in early hominid lifeways. Afr Archaeol Rev. 1985;3:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brain CK. The occurrence of burnt bones at Swartkrans and their implications for the control of fire by Early Hominids. In: Brain CK, editor. Swartkrans: A Cave's Chronicle of Early Man. Pretoria, South Africa: Transvaal Museum; 1993. pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sillen A, Hoering T. Chemical characterization of burnt bones from Swartkrans. In: Brain CK, editor. Swartkrans: A Cave's Chronicle of Early Man. Pretoria, South Africa: Transvaal Museum; 1993. pp. 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brain CK, Sillen A. Evidence from the Swartkrans Cave for the earliest use of fire. Nature. 1988;336:464–466. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goren-Inbar N, et al. Evidence of hominin control of fire at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. Science. 2004;304:725–727. doi: 10.1126/science.1095443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richter D, Alperson-Afil N, Goren-Inbar N. Employing TL methods for the verification of macroscopically determined heat alteration of flint artefacts from Palaeolithic contexts. Archaeometry. 2011;53:842–857. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alperson-Afil N, et al. Spatial organization of hominin activities at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. Science. 2009;326:1677–1680. doi: 10.1126/science.1180695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg P, Weiner S, Bar-Yosef O, Xu Q, Liu J. Site formation processes at Zhoukoudian, China. J Hum Evol. 2001;41:483–530. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2001.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner S, Xu Q, Goldberg P, Liu J, Bar-Yosef O. Evidence for the use of fire at Zhoukoudian, China. Science. 1998;281:251–253. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berna F, Goldberg P. Assessing Paleolithic pyrotechnology and associated hominin behavior in Israel. Isr J Earth Sci. 2007;56:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg P, Berna F. Micromorphology and context. Quat Int. 2010;214:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandgathe DM, et al. On the Role of fire in Neandertal adaptations in Western Europe: Evidence from Pech de l'Azé and Roc de Marsal, France. PaleoAnthropology. 2011;2011:216–242. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaumont PB, Vogel JC. On a timescale for the past million years of human history in central South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 2006;102:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaumont PB. The edge: More on fire-making by about 1.7 million years ago at Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa. Curr. Ant. 2011;52:585–595. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chazan M, et al. Radiometric dating of the Earlier Stone Age sequence in excavation I at Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa: Preliminary results. J Hum Evol. 2008;55:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matmon A, Ron H, Chazan M, Porat N, Horwitz LK. Reconstructing the history of sediment deposition in caves: A case study from Wonderwerk Cave. GSA Bull. 2012;124(3-4):611–625. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flügel E. Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks: Analysis, Interpretation and Application. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onac BP, Effnberger HS, Breban RC. High-temperature and “exotic” minerals from the Cioclovina Cave, Romania: A review. Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai, Geologia. 2007;52:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuman K, Field AS, McNabb AJ. La Préhistoire ancienne de l'Afrique méridionale: contributions des sites à hominidés d'Afrique du Sud. In: Sahnouni M, Pigeaud R, editors. La Paléolithique en Afrique: L'Histoire la Plus Longue. Paris: Errance; 2005. pp. 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courty MA, Goldberg P, Macphail RI. Soils and Micromorphology in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoops G. Guidelines for Analysis and Description of Soil and Regolith Thin Sections. Madison, WI: Soil Science Society of America; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berna F, et al. Sediments exposed to high temperatures: Reconstructing pyrotechnological practices in Late Bronze and Iron Age strata at Tel Dor (Israel) J Archaeol Sci. 2007;34:358–373. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berna F. In: Scientific Methods and Cultural Heritage. An Introduction to the Application of Materials Science to Archaeometry and Conservation Science. Artioli G, editor. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2010. pp. 364–367. [Google Scholar]