Abstract

Intensive gene targeting studies in mice have revealed that prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs) play important roles in murine embryonic development; however, the expression patterns and function of these genes during embryogenesis of other vertebrates remain largely unknown. Here we report the molecular cloning of phd1 and systematic analysis of phd1, phd2, and phd3 expression in embryos as well as adult tissues of Xenopus laevis. All three phds are maternally provided during Xenopus early development. The spatial expression patterns of phds genes in Xenopus embryos appear to define a distinct synexpression group. Frog phd2 and phd3 showed complementary expression in adult tissues with phd2 transcription levels being high in the eye, brain, and intestine, but low in the liver, pancreas, and kidney. On the contrary, expression levels of phd3 are high in the liver, pancreas, and kidney, but low in the eye, brain, and intestine. All three phds are highly expressed in testes, ovary, gall bladder, and spleen. Among three phds, phd3 showed strongest expression in heart.

1. Introduction

Aerobic organisms in response to inadequate oxygen availability evolved sophisticated systems to adapt the environment, in which hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) play pivotal roles [1–3]. HIF functions as a heterodimer consisting of an unstable alpha subunit, such as HIF1α or HIF2α, and a stable beta subunit, such as HIF1β, also called ARNT1. Under normoxic conditions, the constitutively expressed alpha subunits are hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylase domain containing proteins, such as PHDs and FIH, whose activity is absolutely dependent on oxygen. The hydroxylation generates binding sites for the von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL) tumor suppressor protein, a component of a ubiquitin ligase complex. Consequently, the alpha subunits are polyubiquitinated and subjected to proteasomal degradation [1, 3]. In contrast, under hypoxic conditions, the activity of PHD proteins is compromised due to low oxygen level and HIF alpha subunits are stabilized, which form active heterodimers with HIF1β to transcriptionally activate 100–200 genes, including genes involved in erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, autophagy, and energy metabolism [3].

The PHD proteins belong to an Fe(II) and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenase superfamily. There is only a single PHD family member called Egl9 in worm Caenorhabditis elegans and in the fly Drosophila melanogaster, while higher metazoans like the vertebrates contain three PHD genes [2, 3]. Although egl9-mutant worms are viable [4, 5], inactivation of egl9 in drosophila and Phd2 in mice, respectively, both resulted in embryonic lethality [6, 7]. It is intriguing to investigate if deletion of any phd genes could cause a lethal phenotype in other vertebrate organisms. Phd1−/− and Phd3−/− mice were normal [7]; however, sophisticated compound and conditional knockout of Phd1, 2, and 3 in mice has revealed an important oxygen sensing function of PHDs in angiogenesis [8, 9], erythropoiesis [10–12], and cardiogenesis [7, 13, 14]. The tissue- or cell-type-specific functions of Phds defined in mice are well correlated with their abundant expression in corresponding tissues and cells. Except for an early report on the characterization of the temporal mRNA expression profile of phd2 and phd3 in Xenopus [15], it appears that there are no systematic studies on phd genes in other vertebrate organisms. Here, we cloned the open reading frame of phd1 and examined the temporal and spatial expression profiles of three phd genes in developing Xenopus laevis embryos as well as in adult tissues. Our data provide a basis for further functional analysis of these genes in the frog system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cloning of Xenopus laevis phds

As the Xenopus laevis phd1 (BC159341) in GenBank database is only a partial cDNA lacking the 5′ terminal sequences, we designed the upstream primer (5′ ACTCTGATCTGCAGTAGGAGTTGAAT 3′) according to the sequence of phd1 locus in Xenopus tropicalis genome sequence and downstream primer (5′ ATCCCTGTTACACAGTACCAGGGCACGAG 3′) from the partial phd1 cDNA (BC159341) sequence and successfully amplified the whole open reading frame of Xenopus laevis phd1 by RT-PCR using Xenopus laevis tadpole cDNA as templates. The obtained PCR fragment was cloned into pGEMT-easy (Promega) vector, verified by sequencing, and deposited in GenBank database with accession number (GU108333.1). Xenopus laevis phd2 and phd3 cDNAs were also cloned into pGEMT-easy (Promega) by RT-PCR with the following primers designed according to their sequences in GenBank database. phd2: forward 5′ AATGGCTGGTGGAGGAAGCGAGGGTTCTAAC 3′ and reverse 5′ TTCTAGACTTCTTTAACAGCTGGATCAGATG 3′; phd3: forward 5′ TATGCCGCCAGGATCTCCCCCATTCGATTTC 3′ and reverse 5′ TCAGCTTTCTTTAGTGGGAGGCTCTTCTCTG 3′. These primers were chosen to clone less conserved regions among three phds and thus to reduce possible cross signals during whole mount in situ hybridization with antisense probes generated from these plasmids.

2.2. Embryo Manipulation

Wild-type Xenopus laevis eggs were obtained by injecting 1000 IU of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) into the dorsal lymph sacs of adult females 6–8 hours before egg collection. Eggs were fertilized in vitro with minced testes, dejellied with 2% cysteine hydrochloride (pH 7.8–8.0) 30 minutes after fertilization, and cultured in 0.1X MBS (1.76 mM NaCl, 48 μM NaHCO3, 20 μM KCl, 200 μM Hepes, 16 μM Mg2SO4, 8 μM CaCl2, 6 μM Ca(NO3)2, pH 7.4) buffer. Embryos were staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber [16].

2.3. RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

Freshly collected tissues were powdered with mortar in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA from embryos and powdered tissues was extracted by using Trizol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction and was digested with DNaseI (Roche). First strand of cDNA was synthesized using superscript I M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The annealing temperatures and PCR cycle numbers (in parentheses) and the sequences of primers used in the RT-PCR reactions are as follows: phd1: (55°C, 28) forward 5′ CAGTCAGAGGACCATACCATC 3′ and reverse 5′ CCTTTGCATCGAAATACCAG 3′; phd2: (55°C, 28) forward 5′ CACGGCATCTTTGTGCTTGA 3′ and reverse 5′ GAGTCTTTGCATCCCATTGTTTAT 3′; phd3: (55°C, 28) forward 5′ TGCTCTGTGGCAACCGACTT 3′ and reverse 5′ CATGAGGGTTACGCCTATCAG 3′; ornithine decarboxylase: (55°C, 23) forward 5′ TGAATTGATGAAAGTGGCAAGG 3′ and reverse 5′ CAGGGCTGGGTTTATCACAGAT 3′.

2.4. Whole Mount In Situ Hybridization

Embryos were fixed in MEMFA (0.1 M MOPS pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 3.7% Formaldehyde) for 1 hour at room temperature and stored in ethanol at −20°C. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed in principle as described by Harland [17], with modifications as reported in Hollemann et al. [18]. To generate digoxigenin-labeled antisense probes, the phd1/pGEMT-easy, phd2/pGEMT-easy, and phd3/pGEMT-easy plasmids were linearized with SalI and transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of Xenopus laevis phd1

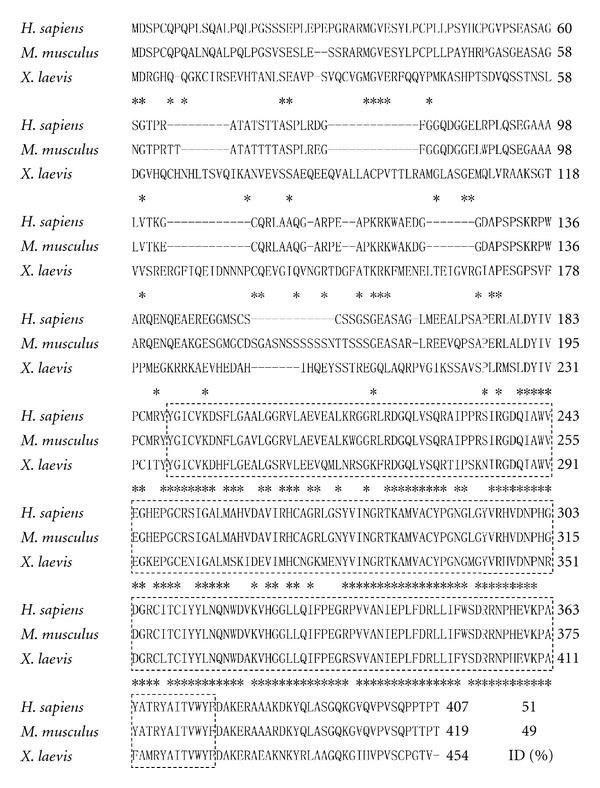

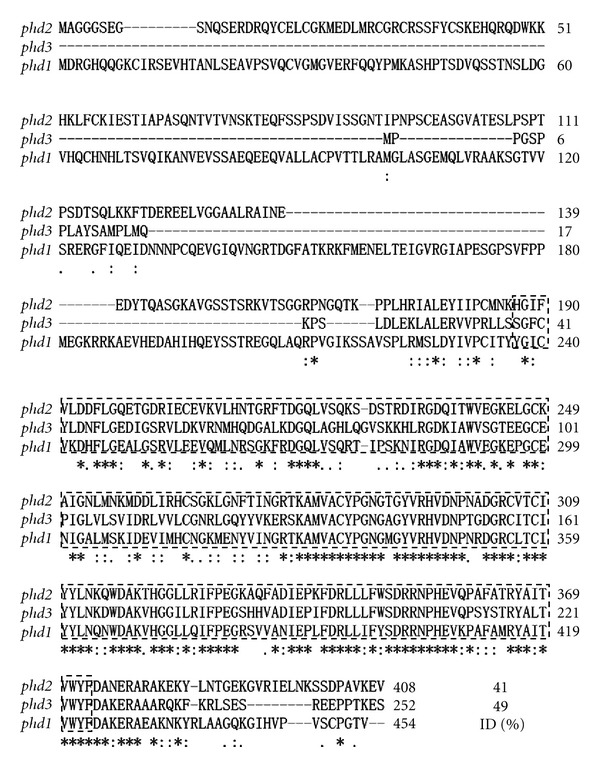

There are three mammalian PHD genes, namely PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 [3]. Isolation of Xenopus laevis homologues of PHD2 and PHD3 has been reported [15]. The amino acid sequence deduced from the whole open reading frame of Xenopus laevis phd1 shares 51.6% and 49.2% identity with human and mouse PHD1, respectively. Within the highly conserved prolyl 4 hydroxylase domain, the frog sequence shares 80.7% and 80.2% identity with human and mouse prolyl 4 hydroxylase domains, respectively (Figure 1). Among three Xenopus laevis phds, the primary amino acid sequence of phd1 shares 41% and 49% identity with those of phd2 and phd3, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Predicted primary sequence of Xenopus phd1 in comparison with human and mouse Phd1. Stars indicate identical amino acids in all three species. Hyphens represent gaps introduced for optimizing the alignment. Dashed rectangles demarcate the highly conserved prolyl 4 hydroxylase domain. ID stands for the percentage of amino acid identity of Xenopus laevis phd1 in comparison with human and mouse Phd1.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of three Xenopus phds. Stars indicate identical amino acids in all three phds. Hyphens represent gaps introduced for optimizing the alignment. Dashed rectangles demarcate the highly conserved prolyl 4 hydroxylase domain. ID stands for the percentage of amino acid identity of Xenopus laevis phd1 in comparison with Xenopus phd2 and phd3.

3.2. Spatial and Temporal Expression Profiles of phds

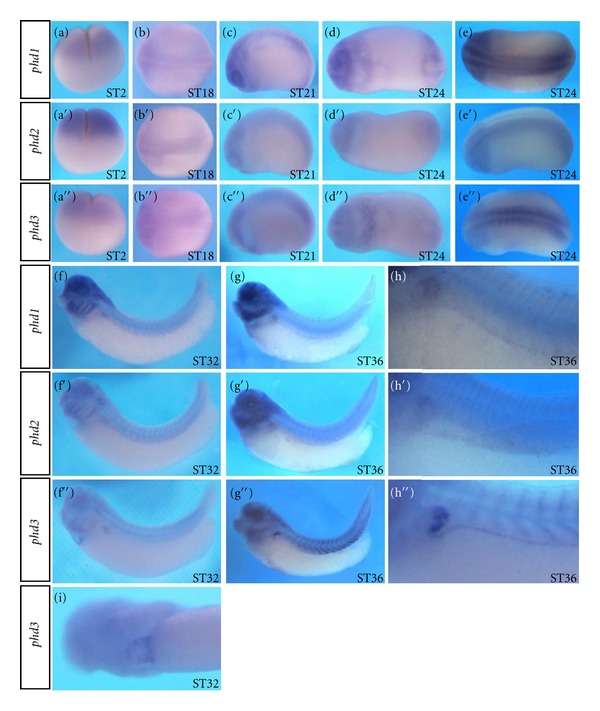

Whole-mount in situ hybridization analyses indicate that at cleavage stages of development, higher levels of maternal transcripts for all three phd genes were detected in the animal hemisphere with phd2 showing the strongest signal (Figure 3(a), 3(a′), and 3(a′′)). At neurula stages of development, all three phds showed weak and relatively broad expression on the dorsal side (Figure 3(b)–3(c′′)). At early tail bud stage of development, the dorsal signals became more restricted with phd1 and phd3 expression being stronger than phd2 expression (Figures 3(e), 3(e′), and 3(e′′)). In addition, a faint signal on the anterior-ventral side of stage 24 embryos was detected for phd1 and phd3 (Figures 3(d) and 3(d′′)). At tail bud stages of development, more differential expression of all three phds was detected in brain, eyes, branchial arches, otic vesicle, and pronephros (Figures 3(f)–3(h′′)). A clear signal was detected for phd3 expression in developing heart (Figure 3(i)).

Figure 3.

Spatial expression of phd1, 2, and 3 in Xenopus embryos revealed by whole-mount in situ hybridization. (a–a′′) Lateral views with animal pole up. (b–b′′) Dorsal views with head towards left. (c–c′′) Lateral views with head towards left. (d–d′′) Ventral views with head towards left. (e–e′′) Dorsal views with head towards left. (f–g′′) Lateral views with head towards left. (h–h′′). Higher magnification views of (g), (g′), and (g′′), respectively. (i) Ventral view of (f′′) with head towards left.

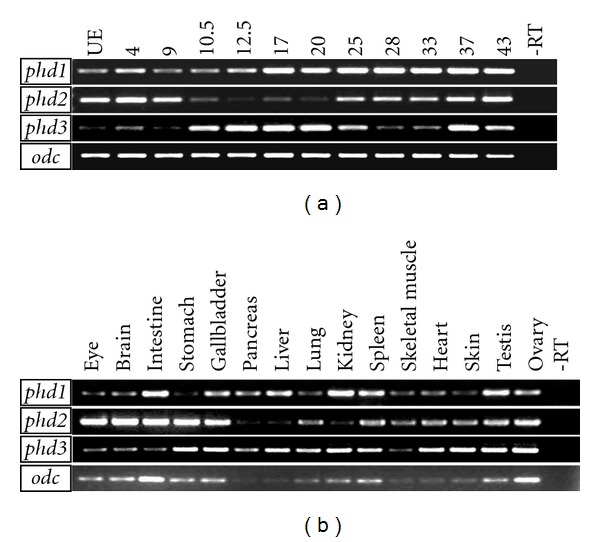

RT-PCR analysis revealed that, up to stage 33, expression levels of phd2 and phd3 just fluctuated in a complementary manner, which has been verified by at least three times of independent experiments (Figure 4(a)). Relatively low level of phd1 expression maintained till gastrulation and constantly higher expression was detected from neurula stages onwards for phd1 (Figure 4(a)).

Figure 4.

Temporal expression profile and adult tissue expression patterns of phd1, 2, and 3 revealed by RT-PCR analyses. (a) Temporal expression profile of phd1, 2, and 3 in Xenopus embryos. (b) Expression of phds in Xenopus adult tissues. odc was employed as a loading control. UE: unfertilized eggs.

3.3. The Expression of phds in Xenopus Adult Tissues

Overall, transcripts of all three phds are detectable in all the adult tissues analyzed (Figure 4(b)). It is of special interest to note that phd2 and phd3 showed complementary expression in several tissues. For instance, phd2 is highly expressed in the eye, brain, and intestine, but low in the liver, pancreas, and kidney. On the contrary, expression levels of phd3 are high in the liver, pancreas, and kidney, but low in the eye, brain, and intestine. All three phds are abundantly expressed in testes, ovary, gall bladder, and spleen. Among three phds, phd3 showed strongest expression in heart.

4. Discussion

In this study, we report the isolation of the whole open reading frame of Xenopus laevis phd1 and characterization of the expression profiles of all three phd3 in Xenopus embryos as well as in adult tissues. Consistent with the previous report [15], we detected a complementary fluctuating temporal expression profile of phd2 and phd3 during Xenopus early embryogenesis. Furthermore, we found complementary expression of phd2 and phd3 in several adult tissues. In mice, several lines of evidence have indicated that PHD2 functionally coordinates with PHD3 and Phd3 is induced upon Phd2 loss [13, 14]. The functional link between phd2 and phd3 in Xenopus remains to be investigated.

phd3 expression in early Xenopus embryos revealed by whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis is reminiscent of zebrafish phd3 expression [19]. Xenopus fih and hif1αshowed similar spatial expression patterns (data not shown). Thus, in Xenopus, it appears that the oxygen homeostasis-related genes, phd1, 2, 3, fih, and hif1α, may constitute a synexpression group. Consistent with the data in mice [20], Xenopus phd3 also showed highest levels of expression in adult heart. All three phds display expression in the pronephros. It has yet to be defined if Xenopus phds play specific roles in the heart and kidney development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from the National Basic Research Program of China (2009CB941202) and the Key Project of Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX2-YW-R-083).

References

- 1.Aragonés J, Fraisl P, Baes M, Carmeliet P. Oxygen sensors at the crossroad of metabolism. Cell Metabolism. 2009;9(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaelin WG. Proline hydroxylation and gene expression. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2005;74:115–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaelin WG, Jr., Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Molecular Cell. 2008;30(4):393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein ACR, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, et al. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107(1):43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao Z, Zhang Y, Powell-Coffman JA. Two distinct roles for EGL-9 in the regulation of HIF-1-mediated gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2009;183(3):821–829. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.107284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centanin L, Ratcliffe PJ, Wappner P. Reversion of lethality and growth defects in Fatiga oxygen-sensor mutant flies by loss of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-α/Sima. EMBO Reports. 2005;6(11):1070–1075. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeda K, Ho VC, Takeda H, Duan LJ, Nagy A, Fong GH. Placental but not heart defects are associated with elevated hypoxia-inducible factor α levels in mice lacking prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26(22):8336–8346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00425-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan L-J, Takeda K, Fong G-H. Prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 (PHD2) mediates oxygen-induced retinopathy in neonatal mice. American Journal of Pathology. 2011;178(4):1881–1890. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda K, Cowan A, Fong GH. Essential role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis of the adult vascular system. Circulation. 2007;116(7):774–781. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minamishima YA, Kaelin WG., Jr. Reactivation of hepatic EPO synthesis in mice after PHD loss. Science. 2010;329(5990):p. 407. doi: 10.1126/science.1192811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Bardeesy N, Cullen D, Bronson RT, Kaelin WG. Somatic inactivation of the PHD2 prolyl hydroxylase causes polycythemia and congestive heart failure. Blood. 2008;111(6):3236–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeda K, Aguila HL, Parikh NS, et al. Regulation of adult erythropoiesis by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Blood. 2008;111(6):3229–3235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-114561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minamishima YA, Moslehi J, Padera RF, Bronson RT, Liao R, Kaelin WG., Jr. A feedback loop involving the Phd3 prolyl hydroxylase tunes the mammalian hypoxic response in vivo. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(21):5729–5741. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00331-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moslehi J, Minamishima YA, Shi J, et al. Loss of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase activity in cardiomyocytes phenocopies ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;122:1004–1016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.922427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imaoka S, Muraguchi T, Kinoshita T. Isolation of Xenopus HIF-prolyl 4-hydroxylase and rescue of a small-eye phenotype caused by Siah2 over-expression. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;355(2):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis. 2 edition. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North-Holland Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harland RM. In situ hybridization: an improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods in Cell Biology. 1991;36:685–695. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollemann T, Panitz F, Pieler T. A Comparative Methods Approach to the Study of Oocytes and Embryos. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1999. In situ hybridization techeniques with Xenopus embryos; pp. 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Rooijen E, Voest EE, Logister I, et al. Zebrafish mutants in the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor display a hypoxic response and recapitulate key aspects of Chuvash polycythemia. Blood. 2009;113(25):6449–6460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-167890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieb ME, Menzies K, Moschella MC, Ni R, Taubman MB. Mammalian EGLN genes have distinct patterns of mRNA expression and regulation. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2002;80(4):421–426. doi: 10.1139/o02-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]