Abstract

The authors summarize evidence from a multiyear study with secondary students with reading difficulties on (a) the potential efficacy of primary-level (Tier 1), secondary-level (Tier 2), and tertiary-level (Tier 3) interventions in remediating reading difficulties with middle school students, (b) the likelihood of resolving reading disabilities with older students with intractable reading disabilities, (c) the reliability, validity, and use of screening and progress monitoring measures with middle school students, and (d) the implications of implementing response to intervention (RTI) practices at the middle school level. The authors provide guidance about prevailing questions about remediating reading difficulties with secondary students and discuss future directions for research using RTI frameworks for students at the secondary level.

Keywords: intensive intervention, reading difficulties, middle school

Models of Response to Intervention

Historical Influences

Response to intervention (RTI) has been conceptualized as a prevention and remediation framework designed to provide universal screening, ongoing progress monitoring and/or curriculum-based measurements with research-based classroom instruction (Tier 1), and increasingly layering of more intensive interventions to meet students’ instructional or behavioral needs (VanDerHeyden & Burns, 2010; Vaughn & Fuchs, 2003). There are two primary ways RTI has been implemented. The first involves schoolwide efforts to prevent and treat behavior problems (Donovan & Cross, 2002; Walker et al., 1998). Typically, these approaches use universal screening to identify students with behavior problems after schoolwide approaches to managing behavior effectively are implemented. These models are associated with problem-solving processes in which a decision-making team identifies the behavior problem and proposes research-based practices for addressing the problem, implements selected practices, evaluates their outcome, and then reconvenes to consider whether the problem has been resolved, leading to improvements in behavior (Reschly, Tilly, & Grimes, 1999).

The second way RTI has been implemented derives from research on preventing reading and math difficulties in children (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009; VanDerHeyden & Burns, 2010). Universal screening is used to identify students with learning needs in reading and/or math after research-based classroom practices have been implemented. Students with learning needs in reading and math are then provided increasingly intensive interventions often using standardized protocols to deliver interventions and monitor students’ responses. Data generated from both of these approaches are used to determine further interventions or to assist in referral and identification for special education.

These models have been influenced by public health approaches to disease prevention that consider primary health needs through a prevention model (e.g., regular checkups, exercise, appropriate monitoring of blood pressure) and then secondary and tertiary levels of health support that increase in cost and intensity depending on the patient’s initial needs or response to treatment (Vaughn, Wanzek, & Fletcher, 2007). There are many iterations on these models; although a few have been implemented at the secondary level, the vast majority are elementary focused.

RTI in Elementary Schools

RTI is typically associated with the early elementary grades for three reasons: (a) much of the research on screening, assessment and interventions has been conducted in kindergarten through third grade (for a review, see Fletcher, Lyon, Fuchs, & Barnes, 2007), (b) Reading First provided about $1 billion in funding for screening, progress monitoring, and multitiered intervention practices in high-poverty, underperforming schools nationally, providing a jump start to the implementation of RTI-type models in kindergarten through third grade, and (c) the emphasis on prevention established a priority at the early grades with little consideration for what RTI might mean in the older grades. Fletcher, Coulter, Reschly, and Vaughn (2004) identified the most important element of RTI at the secondary level as treatment because screening and identification are largely addressed through the accountability system. They stated, “Why isn’t the first thing done with older students (or adults) struggling with reading, math, and/or writing to provide him or her with intervention?” (p. 325).

Reading Interventions for Secondary Students

The key to implementation of RTI at the elementary level was the availability of evidence-based approaches to reading instruction and the classroom and remedial levels. These interventions are emerging at the secondary level. Empirical syntheses of interventions conducted with secondary students with reading disabilities have revealed that interventions with older readers with reading disabilities are associated with gains in comprehension and that secondary students with reading difficulties can continue to profit from explicit reading instruction (Edmonds et al., 2009; Scammacca et al., 2007), although it is noteworthy that interventions focused specifically on secondary students demonstrating low response to typically effective reading interventions have not been conducted. However, although evidence from researcher-generated measures indicated that vocabulary instruction for older readers was beneficial, gains on standardized measures have not been documented. Also, although interventions represented in previous studies were associated with gains in word study and comprehension, findings from multitiered interventions like those typically provided within an RTI model were not available.

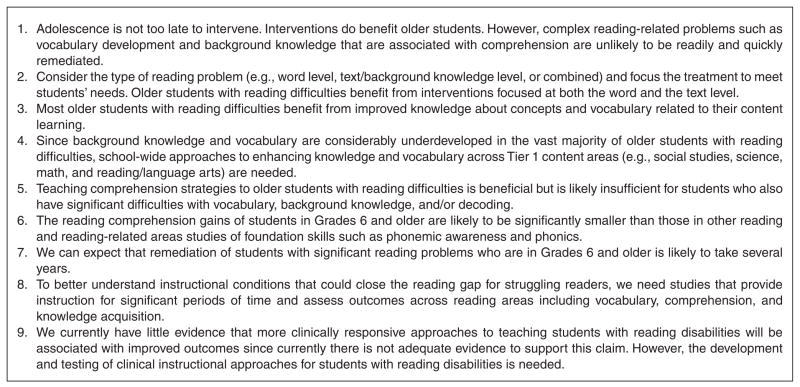

Scammacca et al. (2007) summarized research on reading interventions for students with reading and LD. Based on findings from their meta-analysis and our own research, we provide in Figure 1 guidelines for practice for students with reading disabilities. We recognize that this summary of our research on RTI for older students with reading disabilities provides just one of many frameworks for effectively meeting the instructional needs of students with persistent reading disabilities (Torgesen et al., 2007). We also recognize that as additional research is forthcoming, a revised view of implementation of RTI practices for older students with reading disabilities will be required.

Figure 1.

Implications for RTI practice for secondary students with reading difficulties

Source: Scammacca et al. (2007), Vaughn et al. (2011), Vaughn and Fletcher (2010).

A Conceptual Model for RTI With Secondary Students

For the past 5 years, our research team, with funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Vaughn et al., 2008), has been addressing research questions related to the implementation of RTI with sixth, seventh, and eighth graders who are in middle school settings. Our intention has been to address several fundamental questions related to the development and use of screening and progress monitoring tools as well as secondary (Tier 2) and tertiary (Tier 3) interventions. The goal has been to contribute to improved research knowledge about how RTI might be effectively conceptualized and implemented in secondary settings. For an improved empirical basis for implementing RTI at the secondary level, we identified each of the critical elements of RTI (e.g., screening and progress monitoring, research-based classroom instruction [Tier 1] and interventions [Tiers 2 and 3]) as requiring systematic study. We summarize our research findings from each of these elements and also present what we consider to be critical directions for future research with secondary students.

Progress Monitoring

A major issue for screening and progress monitoring in middle schools is the reliability and validity of the measures. Although there was substantial literature on the reliability, validity, and utility of screening and progress monitoring measures for reading in elementary schools (Stecker, Fuchs, & Fuchs, 2005; Wayman, Wallace, Wiley, Tichá, & Espin, 2007), there was little research on middle school readers when we began our multiyear study with secondary students. More recent studies of relatively smaller samples (e.g., Espin, Wallace, Lembke, Campbell, & Long, 2010), however, have found that oral reading fluency and maze assessments are reliable and valid, which is consistent with our large-sample results. For our study, we administered several individual and group-based assessments using passage reading fluency and a maze procedure to a large sample of struggling and typical readers in Grades 6–8. We also developed and implemented a set of oral reading fluency passages to evaluate the effects of form, difficulty level, growth, and repeated exposure to same and different passages. Finally, norm-referenced assessments of decoding, fluency, and comprehension were administered to evaluate the validity of the measures.

Sample

A total of 1,867 students in Grades 6–8 participated in this middle school study. The sample represented all struggling readers (n = 1,083) in seven urban, rural, and suburban middle schools. Students who were struggling readers did not reliably pass the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS), the state’s criterion-referenced reading comprehension assessment or did not take it because of exemptions for special education status. Thus, students in special education classes were not excluded from the identification procedure, with the only exception being those in special education classes for more pervasive difficulties who did not receive the majority of their programming in general education. Typical readers (n = 784) were randomly selected from these schools since most students passed the TAKS as we did not have the resources to follow all students.

Screening

The first question we asked was whether the state accountability reading measure (TAKS) could be used as a screening assessment. In contrast to early elementary grades, where students are often not routinely assessed, all states administer high-stakes assessments for accountability purposes beginning in Grade 3. Because the burden of assessment is significant for many schools and teachers, we did not want to add to the assessment demands and asked whether the TAKS could be used as a screening assessment. The TAKS is administered each year in the spring beginning in Grade 3. It has good reliability; for example, the internal consistency (coefficient alpha) of the Grade 7 test used in 2005 is .89 (Texas Education Agency, 2006). However, there are limited validity studies. We found clear evidence that the TAKS was a valid assessment of reading comprehension skills as it loaded with other reading comprehension assessments in a latent variable analysis (Cirino et al., 2010). In addition, we found strong overlap of identification rates for struggling readers from the TAKS versus other norm-referenced assessments where “struggling” was indicated by performance below the 20th percentile, with the differences reflecting cut points and measurement error of the tests. However, the TAKS is untimed and does not differentiate students according to the nature of their reading problem (decoding, fluency, comprehension). About a third of the sample was impaired in decoding, fluency, and comprehension, and another third in fluency and comprehension. Less than a fifth had problems only in reading comprehension. These findings indicated that following the TAKS with a fluency screen would help increase the sensitivity of the TAKS and also provide information about the nature of the student’s reading problem.

Oral reading fluency

To assess fluency, we administered several norm-referenced and criterion-referenced measures and also constructed word reading and passage reading fluency measures. Since most of our work focused on the fluency assessments, we present some of these results.

For the Passage Reading Fluency measure, a total of 100 passages were developed in both narrative and expository text structure. All passages averaged approximately 500 words each. Passages ranged in difficulty from a Lexile® text measure of 350 to 1,400 lexiles (Lexile Framework for Reading, 2007). A Lexile® text measure is based on word frequency and sentence length, two strong indicators of text difficulty. Passages were organized into “lexile bands.” Thus, the 100 passages were subdivided into groups of 10 passages. Each subgroup contained 10 passages, 5 expository and 5 narrative texts. All passages within a lexile band were within 110 lexiles of each other.

We then equated the passages to control for form effects using procedures from Francis et al. (2008) and compared equated and unequated passages. We also administered the passages in roughly 2-month intervals five times during the year to assess growth, with students assigned to randomly ordered sequences of stories to evaluate difficulty level. In addition, we had some students read the same passage and others different passages to assess the effects of repeated exposure to the passages. Last, we compared fluency estimates from 1-min samples versus full passages. Basic reliability and validity analyses were conducted.

The results will appear as a series of studies currently under review. In terms of the effects of passage and growth, passage accounted for 55% of the variance in within-student fluency rates (Barth et al., 2011). In accounting for passage effects, difficulty level decreased four words correct per minute (WCPM) per each 100 lexile increase in difficulty, but the effect on student growth was variable and not a major factor in explaining passage variability at the student level. Most of any effect of difficulty level was seen in Grade 6, with little effects of lexile text level on passage reading fluency in Grades 7–8. Although there were complex interactions with reader group (struggling vs. typical), these effects were small, and the amount of within-student growth during the year was relatively small across grades, difficulty level, and group. For grade effects, Grades 7 and 8 students read 5 and 15 WCPM faster than Grade 6 students, respectively. Typical readers read about 7 WCPM faster than struggling readers. Within-student growth was about 12 WCPM from fall to spring. Thus, unlike results of elementary school progress monitoring, the difficulty level of the passages had a small impact on fluency rates in Grade 6 but not Grades 7–8. Rates of growth in WCPM were also relatively small.

In other studies, Barth, Stuebing, et al. (2010) found good evidence for reliability and validity for the mean and median scores, suggesting that in middle schools, either of these scores can be used to summarize performance. The reliability did not vary significantly by virtue of whether a student was a struggling or typical reader. However, although the validity of the measure with other reading comprehension measures was strong for all students, it was lower for the struggling readers, possibly because of range restriction. Barth, Romain, et al. (2010) found little difference in the reliability and validity of 1-min versus full-passage reading. Altogether, these results show that oral reading fluency measures are reliable and valid, that equating is needed to deal with form effects, and that difficulty level and growth have less impact in middle school than elementary grades. These findings suggest that progress monitoring with external measures of oral reading fluency may need to be more widely spaced to demonstrate meaningful growth because the rates of change are relatively small over the course of the year (also see Espin et al., 2010). This does not apply to the use of progress monitoring assessments based on the curriculum that represent mastery assessments, which may be more useful at the secondary level. Both repeated and different passages may be useful.

We also examined whether adding a 1-min passage reading assessment to the equated passages added to the information provided by TAKS. For this analysis, we divided participants according to whether the student presented with decoding, fluency, and comprehension difficulties; fluency and comprehension difficulties; or only comprehension difficulties. TAKS scores were much lower for students with problems in all three domains, but not different for students with fluency and comprehension versus only comprehension difficulties. By adding the 1-min oral reading fluency probe to the information provided by TAKS (routinely collected on all students), we showed that students could be accurately subdivided based on instructional needs in decoding, fluency, and comprehension. In general, we do not see a need for more extensive assessment.

Instructional Approaches and Results at Tiers 1–3

Tier 1 classroom instruction

Tier 1 research-based classroom instruction at the elementary level for reading is often referred to as the core reading program. The expectation is that, through ongoing professional development for teachers and the selection and use of research-based reading programs, students will be provided with the most scientifically based reading instruction. In elementary school, the goal is that approximately 80% of students will make substantial progress in reading leaving about 20% who would require supplemental interventions (Tier 2 or 3) with the vast majority of these students with reading problems having their problems remedied through secondary or Tier 2 intervention. This leaves only students with the most challenging reading problems for Tier 3—many of these students would be identified as having learning disabilities in the area of reading (Fletcher & Vaughn, 2009). We do not think that there is adequate evidence to support these same assumptions about remediation for secondary students.

Tier 1 instruction at the secondary level is conceptually similar but practically more complicated. Although the focus is on the implementation of research-based practices, the challenge is providing these practices in the area of reading across the content areas (e.g., math, social studies, science). For this reason, we conceptualized the Tier 1 intervention at the secondary level as focusing primarily on building vocabulary (e.g., both academic vocabulary and core vocabulary), improving background knowledge (i.e., students who demonstrate adequate background knowledge are more likely to understand what they read), and improving comprehension strategies across content areas (e.g., students practicing summarizing what they read using the same strategies in social studies and science). Although there is a cogent argument for providing discipline specific comprehension strategies (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008), the current evidence on improving reading comprehension with adolescents demonstrates medium to high effects from the comprehension strategies we selected and taught to teachers (What Works Clearing House, 2010). All classroom content teachers (e.g., social studies, science, math, English or language arts) participated in a professional development designed to enhance their knowledge of teaching vocabulary and comprehension within their content area (Denton, Bryan, Wexler, Reed, & Vaughn, 2007; Reed & Vaughn, 2010). Teachers attended a 6-hr professional development session followed by monthly meetings with their study teams and the researcher assigned to the school. The researchers also provided in-class coaching as requested. Thus, vocabulary and comprehension practices were integrated into typical classroom instruction in science, social studies, English or language arts, and math for all students (treatment and comparison) with the goal of enhancing reading comprehension. There was no additional instructional time provided for Tier 1.

There are several significant difference between Tier 1 instruction at the elementary and secondary level: (a) elementary teachers are confident that teaching reading is their responsibility and for many in the early elementary grades their most important responsibility, (b) secondary content area teachers perceive their students need vocabulary and comprehension instruction but consider the coverage of content their primary responsibility, (c) elementary teachers provide reading instruction as a subject with dedicated time whereas secondary teachers are integrating vocabulary and comprehension routines into their content area instruction, and (d) there are many materials designed for elementary reading instruction whereas there are few materials designed to enhance vocabulary and comprehension instruction within the lesson and unit routines of secondary teachers. In addition, secondary schools will already have identified most students with reading difficulties.

An integral element of effective implementation of RTI is enhanced classroom instruction (Tier 1). As discussed earlier, this is more easily conceptualized at the elementary level with designated time for reading than it is at the secondary level where reading instruction is unlikely to have a designated period. However, our experience with the seven middle schools in the three school districts making up the sample was that many (but not all) content teachers craved instructional practices to enhance vocabulary and comprehension as they recognized that many of their students could not understand or access content area texts through reading—other than “reading the texts aloud to them.” Prior to our implementation of the Tier 1 professional development, teachers reported that they were at a loss as to how instruct low readers in their classrooms. For a complete description of the professional development provided, see the Adolescent Literacy Sourcebook (http://www.meadowscenter.org/library/middle_school_instruction.asp). Since all students in all conditions received Tier 1 instruction as a means of enhancing their overall classroom instruction, we could not disaggregate findings separately for Tier 1 intervention. However, teacher reports and observations from coaches suggest beneficial results from integrating a comprehensive approach to enhancing vocabulary and comprehension outcomes in middle schools (Vaughn, Cirino, et al., 2010).

Interventions and Outcomes at Tiers 2 and 3

We conducted two separate studies with the middle school sample described for assessment (Grades 6–8) that included Tier 1 within the study design (Vaughn, Cirino, et al., 2010); however, the effects of Tier 1 were not systematically manipulated as Tier 1 was provided to all students including those in Tier 2 treatment as well as those in Tier 2 comparison. In both studies, three groups of students were identified and included the following: (a) typical readers—these students were meeting grade-level expectations in reading and were provided Tier 1 during their classroom instruction (i.e., enhanced classroom instruction as a result of content area teachers in math, social studies, and science participating in professional development on integrating vocabulary and reading comprehension into their content instruction); (b) struggling readers assigned to researcher treatment—these students were provided Tier 1 during their classroom instruction, but they were also provided an additional class each day in reading (50 min per day) taught by a researcher-hired and -trained teacher who provided an intervention designed to accelerate their performance in word reading, word understanding, and comprehension; and (c) struggling reader comparisons who were not randomly assigned to researcher treatment but many of whom received additional support such as tutorials and after-school reading groups to prepare them to pass the state-level reading tests.

Tier 2: Secondary intervention

At the elementary level, Tier 2 is conceptualized as a prevention approach. However, by the time students are in fourth grade and certainly by secondary school, the intention of prevention is no longer really feasible. For this reason, the secondary intervention (Tier 2) that we provided to students was rather significant. We provided 50 min of additional reading intervention (replacing electives) to treatment students identified as “at risk” on the state-level reading test (scoring below expected levels). All of these students were randomized to either treatment or comparison groups. Students in the treatment condition in sixth grade were provided a daily intervention by trained reading specialists who were monitored and hired by the research team (Vaughn, Cirino, et al., 2010). Students in seventh and eighth grade assigned to treatment were provided either small-group instruction (about five students) or large-group instruction (about 10 students; Vaughn, Wanzek, et al., 2010). The Tier 2 treatment that we provided to students for one class period per day (50 min) for the entire school year was organized into three phases of instruction that varied in emphasis. The Phase I intervention emphasized word study and fluency with supplemental instruction in vocabulary and comprehension. Phase I consisted of approximately 25 lessons taught over 7 to 8 weeks depending on student mastery. The daily lessons included Word Study to teach advanced decoding of multisyllabic words using REWARDS Intermediate (Archer, Gleason, & Vachon, 2003). Progression through lessons was dependent on students’ mastery of sounds and word reading. Students received daily instruction and practice with individual letter sounds, letter combinations, and affixes. In addition, students received instruction and practice in applying a strategy to decode multisyllabic words by breaking them into known parts. Students also practiced breaking words into parts to spell. Word reading strategies were applied to reading in context in the form of sentences and passage reading daily. During Phase I, high levels of teacher support and scaffolding were provided to students in applying the multisyllabic word reading strategy to reading words and connected text, and spelling words. Fluency instruction was promoted by using oral reading fluency data and pairing higher and lower readers for partner reading. Students engaged in repeated reading daily with their partner with the goal of increased fluency (accuracy and rate). Partners took turns reading orally while their partner read along and marked errors. The higher reader always read first. After reading, partners were given time to go over errors and ask questions about unknown words. Partners read the passage three times each and graphed the number of words read correctly. The teacher was actively involved in modeling and providing feedback to students. Vocabulary was taught daily by teaching the meaning of the words through basic definitions and providing examples and non-examples of how to use the word. New vocabulary words were reviewed daily with students matching words to appropriate definitions or examples of word usage. Comprehension was taught during and after reading by asking students to address relevant comprehension questions of varying levels of difficulty (literal and inferential). Teachers assisted students in locating information in text and rereading to identify answers.

In Phase II of the intervention, the emphasis of instruction was on vocabulary and comprehension with additional instruction and practice provided for applying the word study and fluency skills and strategies learned in Phase I. Lessons occurred over a period of 17–18 weeks depending on students’ progress. Word study and vocabulary were taught through daily review of the word study strategies learned in Phase I by applying the sounds and strategy to reading new words. Focus on word meaning was also part of word reading practice. Students were also taught word relatives and parts of speech (e.g., politics, politician, politically). Finally, students reviewed application of word study to spelling words. Vocabulary words for instruction were chosen from the text read in the fluency and comprehension component. Three days a week teachers used REWARDS Plus Social Studies lessons and materials. Two days a week teachers used novels with lessons developed by the research team. Fluency and comprehension were taught with an emphasis on reading and understanding text through discourse or writing. Students spent 3 days a week reading and comprehending expository social studies text (REWARDS Plus; Archer, Gleason, & Vachon, 2005) and 2 days a week reading and comprehending narrative text in novels. Content and vocabulary needed to understand the text were taught prior to reading. Students then read the text at least twice with an emphasis on reading for understanding. During and after the second reading, comprehension questions of varying levels of complexity and abstraction were discussed with students. Students also received explicit instruction in generating questions of varying levels of complexity and abstraction while reading (e.g., literal questions, questions requiring students to synthesize information from text, and questions requiring students to apply background knowledge to information in text), identifying the main idea, summarizing, and strategies for addressing multiple-choice, short-answer, and essay questions.

Phase III continued the instructional emphasis on vocabulary and comprehension with more time spent on independent student application of skills and strategies. Phase III occurred over approximately 8–10 weeks.

Tier 2: Evaluation results

This multitiered, multiyear design of our studies allowed us to answer two primary questions: (a) Overall, how effective was the treatment in enhancing students’ outcomes in reading? and (b) Do students who are assigned to small-group instruction outperform students in large-group instruction? A brief answer to the first question is that for students with reading difficulties, the secondary (Tier 2) treatment in addition to the enhanced classroom instruction (Tier 1) was associated with gains in decoding, reading fluency and comprehension (d = 0.16) over students with reading difficulties who received from the research team only the enhanced classroom instruction (Tier 1)—although many of the Tier-1-only students also received interventions from their schools (Vaughn, Cirino, et al., 2010). These gains compare favorably with large-scale studies of secondary students in which interventions have repeatedly demonstrated no effects or very small effects (Corrin, Somers, Kemple, Nelson, & Sepanik, 2008; James-Burdumy et al., 2009; Kemple et al., 2008). Research consistently reports small impact with adolescents with reading difficulties, but we would expect that our impact on the treatment compared with control would be influenced by the fact that both groups received Tier 1 instruction. With respect to the second question, we did not discern statistically significant differences for secondary students with reading difficulties who were taught in a small group (n = 5 students per group) versus students who were taught in a larger group (n = 10–14 students per group; Vaughn et al., 2009). Since students in both grouping formats received the same intervention (described previously) and it was fairly standardized, we interpreted the findings that group size may matter less when a standardized intervention is provided. As a follow-up to these studies, we examined separately the findings for the students with disabilities (largely students with learning disabilities—LD; Wanzek, Vaughn, Roberts, & Fletcher, in press). Effects are reported as eta-squared and were moderate for sight word (.054) and small for phonemic decoding and passage comprehension (.018 and .017) but in favor of students with LD who were provided the treatment. It is important to note that all students (treatment and comparison) continued with their special education treatment.

Fidelity of implementation is an issue of high importance, as is the extent to which the time we allocated to treatment corresponded with the actual time students received treatment. As we report in more detail in other papers (Vaughn, Cirino, et al., 2010; Vaughn, Wanzek, et al., 2010; Vaughn et al., 2011), fidelity of treatment was high largely because the research team hired and supervised all of the treatment teachers and actual treatment time was documented as corresponding with expected treatment time.

Tier 3: Tertiary intervention

As part of our RTI model, middle school students who were identified as “at risk” and provided a yearlong treatment (see description above of Tier 2) were assessed at the end of the year and based on their performance were either exited from interventions (i.e., performance suggested they no longer needed reading intervention) or retained in the intervention (i.e., performance suggested they required additional intervention). Aligned with a RTI model, we were interested in making the intervention more intensive. Since these students received a year of intervention, we hypothesized that these students who were “inadequate responders” to the previous yearlong intervention and would benefit from an “individualized treatment” designed to meet their needs. To test this hypothesis, we randomly assigned “inadequate responders” to one of two conditions: individualized treatment or standardized treatment. Comparison students who were also “inadequate responders” remained in the comparison condition (Vaughn et al., 2011).

We were interested in the relative effects of individualized interventions in contrast with standardized interventions for students who were minimal responders to the Tier 2, yearlong intervention because an underlying premise within instructional models for teaching students with LD (i.e., reading disabilities) is that interventions need to be tailored to meet their individual needs. Aligning instruction with students’ instructional needs yields beneficial outcomes. In contrast with standardized interventions, whereby all students in the condition are provided the same treatment protocol, the effectiveness of individualized interventions that respond to the differentiated needs of students has been understudied. For example, in their synthesis of Tier 3 interventions with early elementary grade students, Wanzek and Vaughn (2007) identified no quasi-experimental or experimental studies that provided individualized interventions. All of the studies that met criteria utilized more or less standardized interventions. Similarly, in their synthesis of interventions with older students with reading difficulties, Scammacca et al. (2007) reported that all of the studies used some variation on a standardized intervention approach.

Understanding the relative effects of individualized interventions may be particularly important with older students since a more clinical approach to responding to students’ learning needs may be necessary to address the range of reading problems represented in older readers including the gap between their reading performance and grade-level expectations. However, there may be advantages to standardized interventions, including that they require less ongoing clinical judgment by teachers, offering a structure that reduces planning and decision making. It is conceivable that these more standardized approaches allow teachers to be attentive to individual students while teaching since the format and organization of instruction are already predetermined. For these reasons, we investigated the relative effects of a standardized intervention compared with an individualized intervention for older students whose response to a 1-year standardized intervention the previous year was low. As part of our current study with older students with persistent reading difficulties, we have defined individualized intervention as implementing instruction that may change frequently throughout the intervention period to match changes in individual student needs. Although individualized approaches have been used in practice (e.g., Ikeda, Tilly, Stumme, Volmer, & Allison, 1996; Marston, Muyskens, Lau, & Canter, 2003) and are considered best clinical practice in LD, there is little research evidence to support this approach. More specifically, outcome data from experimental designs employing comparison or control groups have not been reported, leaving questions as to the direct effects of these individualized implementations (Burns, Appleton, & Stehouwer, 2005; D. Fuchs, Mock, Morgan, & Young, 2003).

As is typically the case when individualized instruction is provided to students with LD, students in the individualized treatment were taught in very small groups, as were students in the standardized treatment. In the individualized intervention within our study, teachers were taught to instruct students on the same research-based components of reading instruction (i.e., word study, fluency, comprehension, vocabulary) as teachers in the standardized intervention protocol. Considering that time in instruction was controlled, there were several significant differences between the two treatments: (a) the individualized intervention had an increased emphasis on flexibility in lesson planning and overall instructional decision making, with a clinical model using diagnostic assessment, individually tailored instruction, ongoing progress monitoring, and adjustment in instruction based on students’ response; (b) the individualized treatment also provided flexibility in text selection, and teachers were able to spend more time conferencing with students on an individual basis to set goals and increase motivation (for further description of the individualized and standardized approach, see Vaughn et al., 2011).

Tier 3: Results

We interpret the findings from this study as providing guidance for instruction of middle school students with LD since the students in the study were low responders to a yearlong intervention provided the previous year. Did students who were provided the individualized intervention outperform students who were provided the standardized intervention? Findings did not confirm our hypothesis that students in the individualized condition would outperform those in the standardized condition (Vaughn et al., 2011). We expected that students whose instruction mirrored their needs (e.g., more word study instruction for students with low word reading, more comprehension instruction for students with greater needs in that area) would outperform similar students who were provided a standardized treatment. Though these findings are not aligned with clinical teaching (D. Fuchs, Fuchs, & Steckler, 2010), they are similar to previous research on beginning readers with reading difficulties in which a more standardized treatment was compared with a more responsive or individualized treatment and yielded no statistically significant difference between the two treatments (Mathes et al., 2005).

We do not think that this single study provides convincing data that more individualized or clinically responsive instruction might not be more effective than standardized approaches for students with intensive reading difficulties, but we do think it provides compelling data to consider when designing interventions for older students with reading disabilities. The findings should also be considered in light of the personnel providing the treatments and their training. The level of training, supervision, and feedback provided to the teachers in this study was extensive and might not represent the level or quality of training typically provided to teachers. When considering the findings for the treatments combined (standardized and individualized combined), statistically significant differences were found for reading comprehension, but not for tasks involving word reading, word attack, or fluency.

We hypothesized that students with identified disabilities might perform significantly better in the individualized rather than standardized condition (Vaughn et al., 2011). Our hypothesis was not confirmed. Students identified with disabilities (special education status) were at more of a disadvantage (poorer outcomes) in the individualized condition than in the standardized condition. This finding was upheld for word attack and for reading comprehension. In addition, the word attack and reading comprehension outcomes for students with disabilities were significantly lower than those of their peers who did not have identified disabilities. This occurred for all three conditions (standardized, individualized, and comparison). We appreciate that there are many possible interpretations of this finding and that individualized approaches that are provided by one specialist to one student might yield more effective outcomes than a standardized approach delivered by one specialist to one student, and we would encourage the testing of this hypothesis in future studies.

Implications for Research and Practice

Research on secondary students with significant reading difficulties yields the following implications for the critical elements of RTI including screening and assessment and tiers of intervention.

Screening and Assessment

Reliable, valid, and efficient screening of secondary students with reading difficulties can be obtained from the state-level reading assessment provided as part of the No Child Left Behind accountability system. An explicit goal of any RTI model is to minimize assessment and maximize instructional opportunities, so taking advantage of existing assessments is intuitively appealing. Although we found that the TAKS and a supplemental fluency assessment were effective, the results might not generalize to other states without evaluation of the validity and utility of the state assessment. Whether the cut point used by the state is adequate also needs careful evaluation.

In terms of progress monitoring, we found that oral reading fluency assessments were reliable and valid but were associated with much less change over time and with small effects of difficulty level when equated. As such, whether to monitor progress at intervals as frequent as in elementary school needs careful consideration. We also wonder if progress assessments based directly on curriculum mastery assessments might be more useful to teachers given the small amount of growth in oral reading fluency. Espin et al. (2010) found that maze assessments were reliable and valid and yielded estimates of slope that related to reading achievement, so this approach to progress monitoring may also be useful. Finally, we found that the addition of an oral reading fluency assessment to a reading comprehension assessment provided significant diagnostic information with minimal teacher time.

Tiers of Intervention for Older Students With Reading Difficulties

Fundamental to the successful implementation of RTI with younger students is the implementation of successively more intensive tiers of intervention to respond to students’ instructional needs based on their lack of response to previously implemented research-based interventions. Our empirical and clinical evidence suggests that the application of this multitiered approach to instruction and intervention is different for older students. Secondary students do not need to “pass through” successively more intensive interventions as in early elementary grades; rather, they can be assigned to less or more intensive interventions based on their current reading achievement scores (L. S. Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2010). Thus, it is technically current performance and instructional need rather than “responsive to intervention” that places them in a secondary or tertiary intervention.

The reasoning is twofold: (a) either these students have already been exposed to research-based interventions in earlier grades that were inadequate and/or (b) students’ needs were not adequately addressed. Empirically, we can identify more and less impaired learners, group them based on diagnostic profiles (e.g., word reading and comprehension), and then assign them based on need to more or less intensive interventions. The best predictor of low RTI in Year 3 of treatment is very low reading achievement at the beginning of Year 1 (Vaughn, 2010). Thus, secondary students with the lowest reading scores can be placed in the most intensive interventions early without having to successively pass through less intensive interventions to document what we already know—they have significant reading problems and require intensive remediation.

Implementing Effective Interventions With Older Readers With Reading Disabilities

Much of the research documenting the efficacy of interventions for younger and older students with reading difficulties could be classified as secondary interventions (for reviews, see Fletcher et al., 2007) in that students are identified as having a reading difficulty, they are provided an intervention for a specified period of time, and the typically “overall” results are reported. Although this approach makes sense for determining the efficacy of interventions with the vast majority of students, it provides inadequate information about the efficacy of interventions for students with reading disabilities or dyslexia. These students may be notably different from poor readers in that they are less responsive to treatment, require more intensive and long-lasting intervention, and may require interventions that are customized to meet their individual learning needs. Furthermore, many of these students have other impairments that interfere with learning to read, including attention problems, low language development, or memory processing problems (Cutting & Scarborough, 2006; Hock et al., 2009). Findings from studies documenting their response to intensive interventions are more limited (for a review at the elementary level, see Wanzek & Vaughn, 2007; for the secondary level, see Reed & Vaughn, 2010).

More difficult to establish have been effective interventions for students who are minimal responders to previously effective interventions (e.g., Denton, Fletcher, Anthony, & Francis, 2006; Vaughn et al., 2009). In Denton et al. (2006), intensive intervention focusing on decoding skills was provided for 2 hr per day over 8 weeks in Grades 2–3 for students who did not respond to Tier 2 intervention as reported in a previous study by Mathes et al. (2005). This 8–week intervention was followed by another 8–week intervention providing fluency and comprehension intervention for 1 hr per day. Although the average amount of improvement (from baseline to posttest, not in relation to a “control” group) was about 0.50 standard deviations, only about half of the students showed a significant response to this intervention, with some showing no gains. We recently conducted an intervention for secondary students with reading disabilities who had been provided a 50-min reading intervention for 2 years. These students, after 2 years of intervention, continued to demonstrate significantly low performance in reading. We then provided a customized, small-group intervention (two to four students with one teacher) for 50 min per day for a 3rd year of intervention. Students gains based on standard scores were minimal, and they did not significantly outperform students in the comparison condition (Vaughn, 2010).

So what types of interventions or instructional practices make sense for older students with intractable reading impairments? There are several issues to consider, most of which are difficult to address confidently given the limited research on older students with persistent reading disabilities; however, we identify what we think research would support as the essential issues.

When Should Compensatory Treatments Begin?

This question has plagued secondary teachers of students with LD for decades. The argument against continuing reading instruction is that there is some cost to continuing to provide reading interventions. Time spent continuing to learn to read takes away from time that could be spent on other content area learning or electives. This is particularly true when the reading intervention replaces the students’ elective, which is often the case at the secondary level. All of these issues require consideration of the views and goals of the student and family as well as the educational context. Our response is that for the vast majority of students, continued reading intervention conducted using texts that build background knowledge and understanding for content learning (e.g., science, social studies) should persist throughout secondary schooling. Our rationale is that older students who are exposed to continuous research-based interventions within content area texts will continue to build academic vocabulary that will benefit content learning broadly as well as acquire word reading and comprehension strategies necessary for future success in school and the work place. In addition, the comparison groups in all our studies typically received some form of reading intervention, and it is possible that growth rates would be even more reduced without this form of support.

What Is the Context for Enhancing Reading Performance for Students With Reading Disabilities?

A modified RTI model is the best context for supporting reading for students with reading disabilities and enhancing reading comprehension and vocabulary for all students. As described earlier, we suggest the first step is to provide a schoolwide effort (Tier 1) for improving vocabulary and comprehension instruction across content areas through ongoing professional development with coaching for content area teachers. We think the second step is to provide ongoing remediation classes to improve comprehension and vocabulary development for students with reading difficulties who are two or more grades below grade-level reading expectations but do not demonstrate very low reading or persistent reading disabilities. We recommend a Tier 3 intervention for students with persistent reading disabilities that includes very small-group instruction (e.g., two to four students) and is as intensive as the school schedule will allow (minimum 50 min per day). In addition, we think that most students with significant reading disabilities will require ongoing reading intervention during the summer.

What Is the Role of Technology?

Our research has not investigated the role of technology in improving reading outcomes for students with reading disabilities. Deshler (personal communication, September 15, 2010) suggests that technology may play an important tool in providing additional time for instruction and may provide the design for an instructional protocol that supports adequate instructional time targeted at the students’ needs with practice and feedback.

What Is the Treatment for Students With Persistent Reading Disabilities?

There is a need for studies to focus on interventions for students at any grade level who are identified as inadequate responders. These students, persistent low responders to treatment, require a special education, and we currently have few research studies specifically addressing their instructional needs. Examples of studies providing interventions to minimal responders to previously research-based interventions have been conducted with elementary students (e.g., Denton et al., 2006; Vaughn et al., 2009; Vellutino, Scanlon, Small, & Fanuele, 2006; Wanzek & Vaughn, 2009). We are aware of only three studies at the secondary level, both derived from the same sample and reviewed previously in this article (e.g., Vaughn, Cirino, et al., 2010; Vaughn et al., 2011; Vaughn, Wanzek, et al., 2010). These studies report moderate gains but limited effects (relative to a comparison group of students receiving some form of reading support) and likely reflect our need for better understanding the instructional demands of secondary students with persistent reading disabilities.

Considerably more focused research is needed to better understand instructional practices across content areas (e.g., math, social studies, science) as well as intensive remedial practices that are associated with improved outcomes for students with significant reading and LD. The role of technology has been underinvestigated, as has the role of clinical teaching approaches (Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., & Steckler 2010). One of many questions we cannot currently adequately answer is the extent to which subtypes of students with LD require markedly different treatments to improve their reading comprehension. Our clinical judgment is that matching treatments to students’ individualized learning needs is beneficial, and further research in this area is needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Grant P50 HD052117 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Archer AL, Gleason MM, Vachon VL. Decoding and fluency: Foundation skills for struggling older readers. Learning Disabilities Quarterly. 2003;26(2):89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Archer AL, Gleason MM, Vachon V. REWARDS intermediate: Multisyllabic word reading strategies. Longmont, CO: Sopris West; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barth AE, Romain M, Cirino PT, Denton CA, Vaughn S, Fletcher JM, Francis DJ. The reliability and validity of one minute vs. full passage fluency among middle school readers. 2010. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Barth AE, Stuebing KK, Fletcher JM, Cirino PT, Francis DJ, Vaughn S. Reliability and validity of the median score when assessing the oral reading fluency of middle grade readers. 2010. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AE, Tolar T, Cirino PT, Francis DJ, Fletcher JM, Vaughn S. Form effects on the oral reading fluency of middle school students. 2011. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Burns M, Appleton JJ, Stehouwer JD. Meta-analytic review of responsiveness-to-intervention research: Examining field-based and research-implemented models. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2005;23(4):381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Cirino PT, Tolar TD, Romain MA, Barth AE, Vaughn S, Denton CA, Francis DJ. Reading components and difficulties in middle school students. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2010;16(Suppl 1):5. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000226. Retrieved from http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayIssue?decade=2010&jid=INS&volumeId=16&issueId=S1&iid=7322548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corrin W, Somers MA, Kemple J, Nelson E, Sepanik S. The enhanced reading opportunities study: Findings from the second year of implementation (NCEE 2009–4036) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cutting LE, Scarborough HS. Prediction of reading comprehension: Relative contributions of word recognition, language proficiency, and other cognitive skills can depend on how comprehension is measured. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2006;10(3):277–299. [Google Scholar]

- Denton CA, Bryan D, Wexler J, Reed D, Vaughn S. Effective instruction for middle school students with reading difficulties: The reading teacher’s sourcebook. Austin: University of Texas System/Texas Education Agency; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ. An evaluation of intensive intervention for students with persistent reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2006;39(5):447–466. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan MS, Cross CT. Minority students in special and gifted education. National Research Council, Committee on Minority Representation in Special Education, Division for Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds MS, Vaughn S, Wexler J, Reutebuch C, Cable A, Tackett KK, Schnakenberg JW. A synthesis of reading interventions and effects on reading comprehension outcomes for older struggling readers. Review of Educational Research. 2009;79:262–300. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espin CA, Wallace T, Lembke E, Campbell H, Long JD. Creating a progress measurement system in reading for middle-school student: Monitoring progress towards meeting high stakes standards. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2010;25:60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Coulter WA, Reschly DJ, Vaughn S. Alternative approaches to the definition and identification of learning disabilities: Some questions and answers. Annals of Dyslexia. 2004;54(2):304–331. doi: 10.1007/s11881-004-0015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Fuchs LS, Barnes MA. Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. New York, NY: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JM, Vaughn S. Response to intervention: Preventing and remediating academic deficits. Child Development and Perspectives. 2009;3(1):30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1750–8606.2008.00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DJ, Santi KL, Barr C, Fletcher JM, Varisco A, Foorman BR. Form effects on the estimation of students’ oral reading fluency using DIBELS. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46(3):315–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Steckler PM. The “blurring” of special education in a new continuum of general education placements and services. Exceptional Children. 2010;76(3):301–323. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Mock D, Morgan PL, Young CL. Responsiveness-to-intervention: Definitions, evidence, and implications for the learning disabilities construct. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2003;18(3):157–171. doi: 10.1111/1540–5826.00072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Fuchs D, Compton DL. Rethinking response to intervention at middle and high school. School Psychology Review. 2010;39(1):22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hock MF, Brasseur IF, Deshler DD, Catts HW, Marquis JG, Mark CA, Stribling JW. What is the reading component skill profile of adolescent struggling readers in urban schools? Learning Disability Quarterly. 2009;32(1):21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda MJ, Tilly WDI, Stumme J, Volmer L, Allison R. Agency-wide implementation of problem solving consultation: Foundations, current implementation, and future directions. School Psychology Quarterly. 1996;11(3):228–243. [Google Scholar]

- James-Burdumy S, Mansfield W, Deke J, Carey N, Lugo-Gil J, Hershey A, Faddis B. Effectiveness of selected supplemental reading comprehension interventions: Impacts on a first cohort of fifth-grade students (NCEE 2009–4032) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kemple J, Corrin W, Nelson E, Salinger T, Herrmann S, Drummond K, Strasberg P. The enhanced reading opportunities study: Early impact and implementation findings (NCEE 2008-4015) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lexile Framework for Reading. Lexile Framework for Reading. Durham, NC: MetaMetrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marston D, Muyskens P, Lau M, Canter A. Problem-solving models for decision making with high-incidence disabilities: The Minneapolis experience. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2003;18(3):187–200. doi: 10.1111/1540–5826.00074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes PG, Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ, Schatschneider C. The effects of theoretically different instruction and student characteristics on the skills of struggling readers. Reading Research Quarterly. 2005;40(2):148–182. [Google Scholar]

- Reed D, Vaughn S. Reading interventions for older students. In: Glover TA, Vaughn S, editors. The promise of response to intervention: Evaluating current science and practice. New York, NY: Guilford; 2010. pp. 143–186. [Google Scholar]

- Reschly DJ, Tilly WD, III, Grimes JP. Special education in transition: Functional assessment and noncategorical programming. Longmont, CO: Sopris West; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Scammacca N, Roberts G, Vaughn S, Edmonds M, Wexler J, Reutebuch CK, Torgesen JK. Interventions for adolescent struggling readers: A meta-analysis with implications for practice. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan T, Shanahan C. Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review. 2008;78(1):40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stecker PM, Fuchs LS, Fuchs D. Using curriculum- based measurement to improve student achievement: Review of research. Psychology in Schools. 2005;42(8):795–819. 0.1002/pits.20113. [Google Scholar]

- Texas Education Agency. Report on the Texas Assessment Program: A report to the 80th Texas legislature. Austin: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Houston DD, Rissman LM, Decker SM, Roberts G, Vaughn S, Lesaux NK. Academic literacy instruction for adolescents: A guidance document from the Center on Instruction. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- VanDerHeyden AM, Burns MK. Essentials of response to intervention. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S. Intensity of intervention to achieve student growth: Perspectives from the NICHD LDRC research projects. Paper presented at the Pacific Coast Research Conference; Coronado, CA. 2010. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Cirino PT, Wanzek J, Wexler J, Fletcher JM, Denton CA, Francis DJ. Response to intervention for middle school students with reading difficulties: Effects of a primary and secondary intervention. School Psychology Review. 2010;39(1):3–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Fletcher JM. Thoughts on rethinking RTI with secondary students. School Psychology Review. 2010;39(2):296–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Fletcher JM, Francis DJ, Denton CA, Wanzek J, Wexler J, Romain MA. Response to intervention with older students with reading difficulties. Learning and Individual Differences. 2008;18(3):338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Fuchs LS. Redefining learning disabilities as inadequate response to instruction: The promise and potential problems. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2003;18(3):137–146. doi: 10.1111/1540–5826.00070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wanzek J, Fletcher JM. Multiple tiers of intervention: A framework for prevention and identification of students with reading/learning disabilities. In: Taylor BM, Ysseldyke JE, editors. Effective instruction for struggling readers. K-6. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2007. pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wanzek J, Wexler J, Barth A, Cirino PT, Fletcher JM, Francis DJ. The relative effects of group size on reading progress of older students with reading difficulties. Reading and Writing. 2010;23(8):931–956. doi: 10.1007/s11145–009–9183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wexler J, Roberts G, Barth AE, Cirino PT, Romain M, Denton CA. The Effects of individualized and standardized interventions on middle school students with reading disabilities. Exceptional Children. 2011;77(4):391–407. doi: 10.1177/001440291107700401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellutino FR, Scanlon DM, Small S, Fanuele DP. Response to intervention as a vehicle for distinguishing between children with and without reading disabilities: Evidence for the role of kindergarten and first-grade interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2006;39(2):157–169. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HM, Forness SR, Kauffman JM, Epstein MH, Gresham FM, Nelson CM, Strain PS. Macro-social validation: Referencing outcomes in behavioral disorders to societal issues and problems. Behavioral Disorders. 1998;24(1):7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S. Research-based implications from extensive early reading interventions. School Psychology Review. 2007;36(4):541–561. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S. Students demonstrating persistent low response to reading intervention: Three case studies. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2009;24(3):151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S, Roberts G, Fletcher JM. Efficacy of a reading intervention for middle school students identified with learning disabilities. Exceptional Children. doi: 10.1177/001440291107800105. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman MM, Wallace T, Wiley HI, Tichá R, Espin CA. Literature synthesis on curriculum-based measurement in reading. Journal of Special Education. 2007;41:85–120. [Google Scholar]

- What Works Clearing House. Adolescent literacy: Reading comprehension. 2010 Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/reports/topic.aspx?tid=15.