Abstract

Bisphosphonates-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (BRONJ) has been reported with increasing frequency in literature over last years, but its therapy is still a dilemma. One hundred ninety patients affected by BRONJ were observed between January 2004 and November 2011 and 166 treated sites were subdivided in five groups on the basis of the therapeutical approach (medical or surgical, traditional or laser-assisted approach, with or without Low Level Laser Therapy (LLLT)). Clinical success has been defined for each treatment performed as clinical improvement or complete mucosal healing. Combination of antibiotic therapy, conservative surgery performed with Er:YAG laser and LLLT applications showed best results for cancer and noncancer patients. Nonsurgical approach performed on 69 sites induced an improvement in 35 sites (50.7%) and the complete healing in 19 sites (27.5%), while surgical approach on 97 sites induced an improvement in 84 sites (86.6%) and the complete healing in 78 sites (80.41%). Improvement and healing were recorded in 31 (81.5%) and 27 (71.5%) out of the 38 BRONJ sites treated in noncancer patients and in 88 (68.75%) and in 69 (53.9%) out of the 128 in cancer patients.

1. Introduction

Bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) management is controversial: there are no evidence-based guidelines in the literature associated with good results for a long-term follow-up, in particular regarding surgical procedures [1]. The main purposes of each treatment are to reduce pain and to control infection and slow the progression of the disease, taking into account as main target the eradication of BRONJ promoting the complete healing. Most of the authors privilege a noninvasive approach especially for asymptomatic stages of BRONJ (Stage I in Ruggiero's staging) [2] but also different surgical approaches have been proposed, with variable types of surgical techniques and with or without discontinuation of bisphosphonates protocols [3–12].

Migliorati and colleagues reported percentages of healing variable from 17.3–17.6% for medical therapy or surgical debridement to 46.3% for free flap or surgical resection procedures [13].

Clinicians should always carefully consider the possibility of extensive surgery in oncological patients because of general status and life expectancy. One of the exclusion criteria was contraindications for surgery under general anaesthesia: this element appears to be an important limit to surgical procedure and confirms the choice for early minimal invasive surgical therapy in stages I and II of BRONJ.

The widespread variant of BRONJ (stage III), in particular those with mandibular fractures, requires bone resection with extension to apparently healthy margins such as bleeding points and normal colour of bone surfaces. On the basis of BRONJ pathogenesis, many authors recommend a large resection because an insufficient elimination of necrotic material may result in a recurrence of bone exposure.

The aim of this retrospective study is to present our experience in a wide number of patients treated with different kinds of surgical and nonsurgical approaches based or not on the use of laser-assisted techniques: the rationale to use laser with low dosages is the biostimulating effect reported in literature on both bone and soft tissues.

2. Material and Methods

One hundred and ninety patients (52 males, 138 females; 62 with multiple myeloma (MM), 85 with bone metastasis (BM), and 43 with osteoporosis (OP), mean age 67.3 ± 10 years) affected by BRONJ were evaluated at the Unit of Oral Pathology and Medicine and Laser-Assisted Surgery of the University of Parma, Italy, between January 2004 and November 2011 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline data of patients: BRONJ stage according to Ruggero's classification, gender distribution, age, and primary disease; BM: bone metastasis, MM: multiple myeloma, OP: osteoporosis and/or rheumatoid arthritis.

| BRONJ Stage | Patients number | Gender | Mean age ± SD | Primary disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | MM | OP | |||||

| Stage I | 34 | Female | 26 | 66.3 ± 11.4 | 15 | 9 | 10 |

| Male | 8 | ||||||

| Stage II | 126 | Female | 92 | 67.9 ± 9.1 | 57 | 43 | 26 |

| Male | 34 | ||||||

| Stage III | 30 | Female | 20 | 65.5 ± 12.2 | 13 | 10 | 7 |

| Male | 10 | ||||||

At the time of BRONJ diagnosis, mean duration of BPT was 26 ± 20 months (ranging between 3 and 72 months) for cancer patients and 90 ± 40 months (ranging between 24 and 144 months) for noncancer patients. Thirty-nine patients (20.5%) were smokers, 22 (11.5%) had diabetes, and 125 patients (65.7%) received long-term corticosteroid treatments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk factors: smoking habits, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease comprehending coagulation disorders, liver disease, and corticosteroids administration; BM: bone metastasis, MM: multiple myeloma, OP: osteoporosis and/or rheumatoid arthritis.

| Primary disease | Patients number | Smoking habits | Diabetes | Hypertension | Heart disease | Liver disease | Corticosteroids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 85 | 25 | 10 | 24 | 21 | 2 | 69 |

| MM | 7 | 6 | 17 | 10 | 2 | 38 | 38 |

| OP | 43 | 7 | 6 | 18 | 6 | 1 | 18 |

Among the 43 “osteoporotic patients,” 2 were treated for rheumatoid arthritis, 39 for osteoporosis, and 2 for both rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporotic, disease; corticosteroids were used in both the patients with rheumatoid arthritis, in 15 out of 39 osteoporotic patients and in 1 out of 2 patients with osteoporosis an rheumatoid arthritis.

One hundred twenty out of 190 patients (63.2%) had mandibular involvement, 53 out of 190 (27.9%) had BRONJ in the maxilla, and 17 out of 190 patients (8.9%) had the involvement of both the jawbones. All these patients were subclassified according to the staging system proposed by the AAOMS in the following groups: Stage I (34/190), Stage II (126/190), and Stage III (30/190) (Table 1).

Treated sites were 166, 38 in noncancer patients and 128 in cancer patients.

Inclusion criteria for treatment were presence of exposed or unexposed symptomatic BRONJ.

Incisional biopsy was performed independently from surgical procedure for BRONJ for lesions suspected to be manifestations of primary disease: specimen of every BRONJ lesions were extracted for histological evaluation.

Patients satisfying inclusion criteria but presenting a very poor health condition or mandibular fracture or diffused Stage III BRONJ not treatable under local anaesthesia were not included in the present evaluation; lack of consent to surgery was also an exclusion criteria for these patients.

An orthopantomography (OPT) and a CT scan of the lesion were obtained in all cases.

In each case the first therapeutic approach was chosen on the basis of the most updated guidelines available at the time of treatment. Surgical approach was taken into account after three consecutive antibiotic cycles not leading to a stable improvement of BRONJ. Each surgical intervention was performed under local anaesthesia and planned according to the extension of the lesion: limited or extensive treatments have been performed with the same kind of approach for both laser-assisted and nonlaser-assisted protocols. In all surgical cases, mucoperiosteal flaps were elevated to visualize and remove the necrotic bone. Surgical instruments included conventional bone burs or Er:YAG laser. A complete closure of the surgical wound was performed through conventional sutures.

In addition to antibiotic or surgical treatment in two separate groups we performed LLLT applications using Nd:YAG laser. According to the ethical standards of the Academic Hospital of Parma, we obtained a specific informed consensus for each patient.

Each patient was treated according a specific protocol (Table 3) as follows.

Table 3.

Protocols used for different therapeutical approaches.

| Treatment | Protocols | |

|---|---|---|

| G1 | Medical therapy | Antibiotic therapy (oral amoxicillin 1 gr 2 times/day with oral metronidazole 250 mg 2 times/day) for two weeks. Mouthwashes with chlorhexidine (0.20%) and hydrogen peroxide (3%) two/three times a day. |

| G2 | Medical therapy + LLLT | G1 protocol + LLLT applications once a week for two months with Nd:YAG Laser (1.25 W, 15 Hz, VSP, 320 μm) of fibre diameter, nonfocused way with scanning method, 2 mm from tissue, for 1 minute and repeated 5 times. |

| G3 | Traditional surgery | Antibiotic treatment prescribed beginning three days prior to the operation and ending 10 days after it. Conservative surgical treatments using traditional surgical instruments consisted in sequestrectomy of necrotic bone or superficial debridement/curettage or corticotomy/surgical removal of alveolar and/or cortical bone. |

| G4 | Traditional surgery + LLLT | G3 protocol + LLLT applications once a week for two months with Nd:YAG Laser (1.25 W, 15 Hz, VSP, 320 μm) of fibre diameter, nonfocused way with scanning method, 2 mm from tissue, for 1 minute and repeated 5 times. |

| G5 | Er:YAG laser surgery | Antibiotic treatment prescribed beginning three days prior to the operation and ending 10 days after it. Bone resection or vaporization of the necrotic areas was obtained with Er:YAG laser with variable parameters, from 250 mJ 20 Hz (VSP) with a fluence of 50 J/cm² up to 300 mJ, 30 Hz and fluence of 60 J/cm2. |

G1: BRONJ sites treated only with antibiotic therapy (oral amoxicillin 1 gr 2 times/day with oral metronidazole 250 mg 2 times/day) for two weeks. Mouthwashes with chlorhexidine (0.20%) and hydrogen peroxide (3%) were also prescribed two/three times a day, sometimes with antimycotic rinses.

G2: BRONJ sites treated with antibiotic therapy (as described in G1) and LLLT. In particular, each lesion received LLLT applications once a week for two months. Each LLLT application was performed with Nd:YAG Laser (1064 nm, Fidelis Plus, Fotona, Slovenia) used at 1.25 W power, 15 Hz frequency, very short pulse mode (VSP) and 320 μm of fibre diameter. The laser light was used in a nonfocused way with a scanning method, 2 mm from tissue, for 1 minute (power density: 268.81 W/cm2, fluence: 14.37 J/cm2) and repeated 5 times [14]: this kind of protocol has been tested for thermal changes on bone and soft tissues without funding any damage depending by thermal elevation [15].

G3: BRONJ sites treated with antibiotic and traditional surgical therapy. In this group antibiotic treatment was usually prescribed beginning three days prior to the operation and ending 10 days after it. Conservative (and, when possible, early) surgical treatments were reserved for these lesions consisting in (a) sequestrectomy of necrotic bone, (b) superficial debridement/curettage and (c) corticotomy/surgical removal of alveolar and/or cortical bone. Operations were performed using traditional surgical instruments: cold blade scalpel to incise mucosal tissues and rotary cutting instruments to remove necrotic bone.

G4: BRONJ sites treated with antibiotic, traditional surgical therapy, and LLLT. Sites were treated with medical and surgical therapy in association with LLLT (Nd:YAG laser) applications. Surgical operations were performed as described in G3 in association with laser Nd:YAG biostimulation (1.25 W power, 15 Hz frequency, fibre of 320 μm). The laser light was used as described in G2. The first application of LLLT was performed during the surgical intervention. The operated site was then treated every week with LLLT applications (same protocol described for G2) for 2 months.

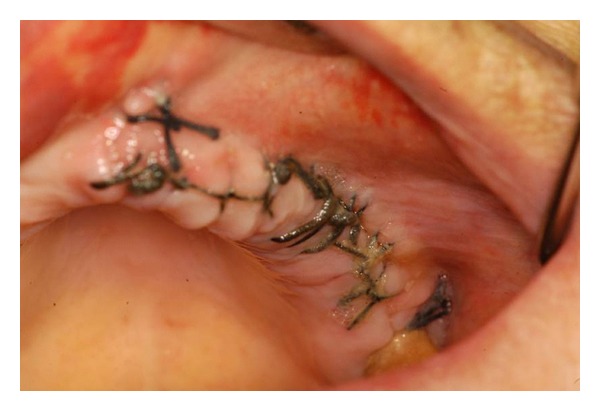

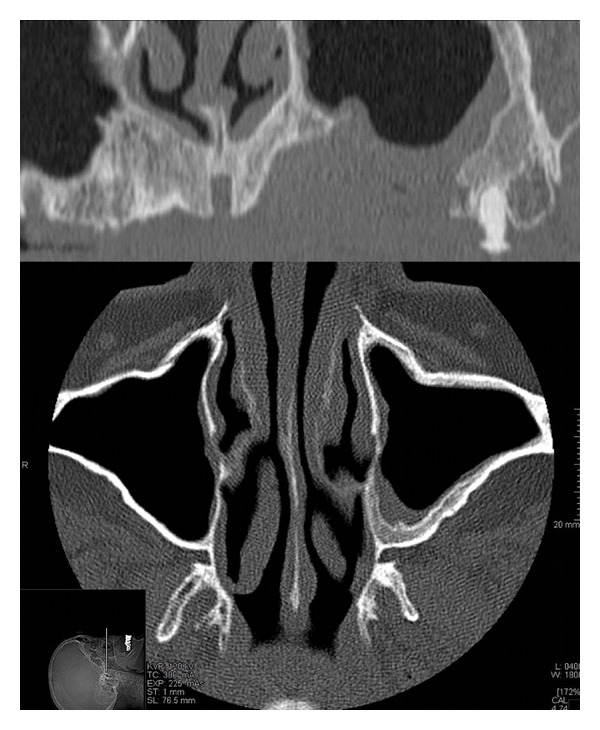

G5: BRONJ sites treated with antibiotic, Er:YAG laser surgical therapy, and LLLT. Surgical removal of necrotic and peripherical bone was achieved with Er:YAG laser. Bone resection or vaporization of the necrotic areas was obtained with variable parameters, from 250 mJ 20 Hz (VSP) with a fluence of 50 J/cm² up to 300 mJ, 30 Hz and fluence of 60 J/cm2. During the surgical intervention we used as irrigation a iodopovidone solution; Er:YAG laser device has been used with a distilled water irrigation system (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) [16].

Figure 1.

Stage III BRONJ in a female patient treated with alendronate for osteoporosis.

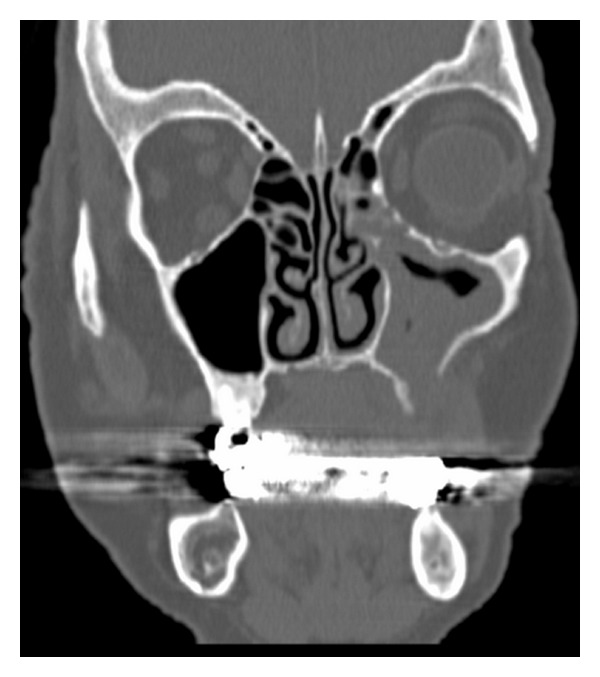

Figure 2.

CT image of patient's maxilla showing sinusitis for maxillary sinus involvement by BRONJ disease.

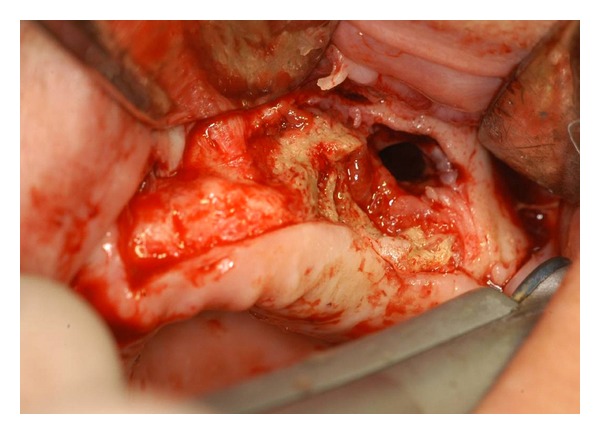

Figure 3.

Bone resection and corticotomy with Er:YAG laser (Step 1): necrotic aspect of the bone is visible.

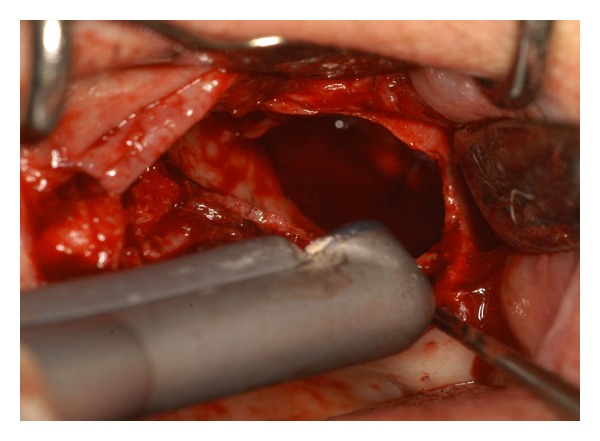

Figure 4.

Bone resection and corticotomy with Er:YAG laser (Step 2): Er:YAG laser vaporization of bone with mirror handpiece (R02) used at distance; visible is the sinus involvement.

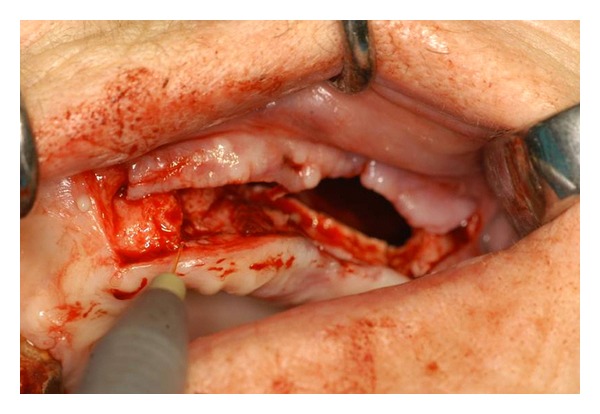

Figure 5.

Intraoperatory biostimulation (Step 3): before suturing, Nd:YAG laser biostimulation was performed with a 320 micrometers fiber for 5 applications of 1 minute each.

Figure 6.

Clinical image of the treated site 1 week after surgery with maintenance of suture.

Figure 7.

Clinical image with persistence of complete healing 1 year after surgery.

Figure 8.

CT images showing the improvement and the healing of the maxillary sinus after the BRONJ treatment.

Results were evaluated by comparing the performed treatments in cancer and non cancer groups; statistical analysis was performed using Fisher test, and results were considered statistically significant for P < 0.05.

3. Results

Nonsurgical approach adopted on 69 sites induced an improvement in 35 sites (50.7%) and complete healing in 19 sites (27.5%), while surgical approach performed on 97 sites induced an improvement in 84 sites (86.6%), of which, 78 completely healed (80.41% of the total).

Improvement was recorded in 31 out of the 38 (81.5%) BRONJ sites treated in non cancer patients and in 88 out of 128 (68.75%) sites in cancer patients. Complete healing was recorded in 27 out of 38 (71.5%) BRONJ sites treated in non cancer patients and in 69 out of 128 (53.9%) sites in cancer patients.

Results in terms of clinical improvement and complete healing are reported in Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7 for both groups of patients. The mean follow-up was 16.44 ± 10.95 months (ranging from 6 to 54).

Table 4.

Clinical results and statistical analysis in noncancer patients in terms of clinical improvement and complete healing. Statistical analysis in cancer patients: comparison between nonsurgical nonlaser-assisted approach (G1) and nonsurgical laser-assisted approach (G2) and comparison between nonsurgical approach (G1 + G2) and surgical approach (G3 + G4 + G5).

| Treatment | Sites | Improvement | % | Healing | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Medical therapy | 10 | 3 | 30 | 2 | 20 |

| G2 | Medical therapy + LLLT | 9 | 9 | 100 | 5 | 55.5 |

| G3 | Traditional surgery | 4 | 4 | 100 | 4 | 100 |

| G4 | Traditional surgery + LLLT | 5 | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 |

| G5 | Er:YAG laser surgery | 10 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 100 |

| G1 versus G2 | P = 0.0031 | P = 0.1698 | ||||

| G1 + G2 versus G3 + G4 + G5 | P = 0.0080 | P < 0.0001 | ||||

Table 5.

Clinical results and statistical analysis in cancer patients in terms of clinical improvement and complete healing. Statistical analysis in cancer patients: comparison between nonsurgical nonlaser-assisted approach (G1) and nonsurgical laser-assisted approach (G2) and comparison between nonsurgical approach (G1 + G2) and surgical approach (G3 + G4 + G5).

| Treatment | Sites | Improvement | % | Healing | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Medical therapy | 22 | 5 | 22.7 | 4 | 18.2 |

| G2 | Medical therapy + LLLT | 28 | 18 | 64.3 | 6 | 21.4 |

| G3 | Traditional surgery | 13 | 7 | 53.8 | 7 | 53.8 |

| G4 | Traditional surgery + LLLT | 34 | 28 | 82.3 | 24 | 70.6 |

| G5 | Er:YAG laser surgery | 31 | 30 | 96.8 | 28 | 90.3 |

| G1 versus G2 | P = 0.0046 | P = 1 | ||||

| G1 + G2 versus G3 + G4 + G5 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 | ||||

| G3 versus G4 + G5 | P = 0.0061 | P = 0.0726 | ||||

Table 6.

Improvement and healing in relation with primary disease and BRONJ stage independently by the therapy (BM: bone metastasis, MM: multiple myeloma, OP: osteoporosis and/or rheumatoid arthritis).

| Primary disease | Stage | Number of sites | Improvement (%) | Healing (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | I | 18 | 14 (77%) | 14 (77%) |

| II | 48 | 37 (77%) | 25 (52%) | |

| III | 3 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| MM | I | 12 | 9 (75%) | 8 (66.6%) |

| II | 44 | 28 (63.6%) | 22 (50%) | |

| III | 3 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| OP | I | 6 | 5 (83.3%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| II | 26 | 22 (84.6%) | 17 (65.4%) | |

| III | 6 | 4 (66.6%) | 4 (66.6%) | |

Table 7.

Improvement and healing in relation with BRONJ stage independently by the primary disease.

| BRONJ stage | Treatment | Sites | Improvement (%) | Healing (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | G1 | 4 | 1 (25%) | 28 (77.7%) | 1 (25%) | 27 (75%) |

| G2 | 6 | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | |||

| G3 | 3 | 3 (100%) | 3 (100%) | |||

| G4 | 7 | 5 (71.4%) | 4 (57.2%) | |||

| G5 | 16 | 16 (100%) | 16 (100%) | |||

| Stage II | G1 | 22 | 7 (31.8%) | 87 (73.7%) | 5 (22.7%) | 64 (54.2%) |

| G2 | 30 | 24 (80%) | 8 (26.6%) | |||

| G3 | 13 | 8 (61.5%) | 8 (61.5%) | |||

| G4 | 32 | 28 (87.5%) | 25 (78.12%) | |||

| G5 | 21 | 20 (95.2%) | 18 (85.7%) | |||

| Stage III | G1 | 6 | 0 (0%) | 4 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (33.3%) |

| G2 | 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| G3 | 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| G4 | — | — | — | |||

| G5 | 4 | 4 (100%) | 4 (100%) | |||

For non cancer patients, a statistically significant result in terms of improvement was recorded from the comparison between BRONJ sites treated with antibiotic therapy alone (G1) and sites treated with local LLLT applications (G2) (P = 0.0031). Moreover, in this group of patients, the comparison between non surgical (G1 + G2) and surgical (G3 + G4 + G5) approach confirmed a statistically significant result in terms of both clinical improvement (P = 0.0080) and healing (P < 0.0001) (Table 4).

For cancer patients a statistically significant difference in terms of improvement was recorded when the BRONJ sites treated with antibiotic therapy alone (G1) were compared to those treated with local LLLT applications (G2) (P = 0.0046). Moreover, in this group of patients, the comparison between non surgical (G1 + G2) and surgical (G3 + G4 + G5) approach reported a statistically significant difference in terms of both clinical improvement (P < 0.0001) and healing (P < 0.0001). The comparison between surgical group without LLLT (G3) and surgical groups with LLLT (G4 + G5) highlighted a statistically significant results in terms of clinical improvement (P = 0.0061) (Table 5).

The comparison between the performed treatment in cancer and non cancer patients showed a significant difference in terms of complete healing for surgical approach (G3 + G4 + G5) (P = 0.200).

4. Discussion

Minimally invasive surgical approach with Er:YAG laser and the use of LLLT represent a good choice for BRONJ treatment especially for antibacterial and biostimulant properties. Surgery performed with Er:YAG and followed by laser biostimulation (LLLT) may determine complete mucosal healing and reduce the microbial component, thus decreasing patient symptoms and providing a higher level of quality of life.

Moreover, Er:YAG laser surgery allows partial or total resection of the jaw without using conventional rotary cutting tools. Preservative surgery can also be performed by gradual vaporization of necrotic bone at increasing depths. Surgical ablation of bone tissue is performed reducing the thermal damage to the adjacent tissue with a quicker healing. The Er:YAG wavelength does not cause coagulation or carbonization. It is therefore possible to clearly distinguish avascular portions of the bone from those that are still vascularised. The Er:YAG laser has great potential for hard tissue treatment due to its high absorption by both water and hydroxyapatite. Such a device provides a clean and precise cut with minimal injury to the adjacent hard and soft tissues while producing an ablated surface favorable for cell attachment.

Conservative surgery, maintaining the overall integrity of the jawbone, is chosen on the basis of specific features in individual cases, ranging from simple curettage to debridement of the necrotic area, from sequestrectomy to resection of larger bone portions. The mini-invasive technique of ablation of the necrotic bone usually induces resurface and causes bleeding from healthy bone which could help in the future revascularization.

As already reported in literature [17, 18], medical therapy alone induces only little improvement of BRONJ lesions in both cancer and non cancer patients.

In nonsurgical-treated patients in both evaluated groups, LLLT applications induced a higher improvement of BRONJ suggesting that the application of LLLT can be useful, especially for patients that cannot be treated surgically.

A statistically significant difference was observed for surgical approach, both for a complete mucosal healing and for a clinical improvement.

The evaluation of the percentage of the sites, with clinical healing achieved with the different treatments, clearly showed how the combination of antibiotic therapy, conservative surgery, and LLLT applications gives better results in both groups of patients.

From our experience, medical approach alone (antibiotic therapy) does not provide permanent clinical outcomes. Symptoms improvement and complete mucosal healing were obtained in 22.7% and 18.2% in cancer patients and in 30% and 20% in osteoporotic patients. Surgical approach performed in early stages of BRONJ induces better results between 53.8% and 100%.

Osteoporotic patients obtained higher levels of improvement with every approach; surgical therapy with or without laser induced complete mucosal healing in all cases (100%).

For cancer patients Er:YAG laser surgery induced complete remission of BRONJ in a statistically significant number of cases (90.3% versus 53.8% obtained with traditional surgery) (Tables 4 and 5); as reported in literature [19–21], this technique allows a mininvasive surgery probably related to the good results of this approach in BRONJ treatment.

Angiero et al. [19], Scoletta et al. [22], and Romeo et al. [23] reported the usefulness of laser biostimulation in BRONJ. Our experience confirms that LLLT in both categories cancer and osteoporotic patients can offer great results in terms of reduction of inflammation and pain control as we already reported [24, 25].

Independently by the performed therapy, the percentage of complete BRONJ healing was related to the stage of disease (Table 7): 75% Stage I, 54.24% Stage II, and 33.3% Stage III.

In conclusion an early conservative surgical approach with Er:YAG laser combined with LLLT, for BRONJ, could be considered as more efficient in comparison to medical therapy alone for the management and quality of life of these patients.

References

- 1.Bagan J, Scully C, Sabater V, Jimenez Y. Osteonecrosis of the jaws in patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates (BRONJ): a concise update. Oral Oncology. 2009;45(7):551–554. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, Landesberg R, Marx RE, Mehrotra B. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws-2009 update. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2009;67(5):2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wutzl A, Biedermann E, Wanschitz F, et al. Treatment results of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Head and Neck. 2008;30(9):1224–1230. doi: 10.1002/hed.20864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wutzl A, Biedermann E, Wanschitz F, et al. Treatment results of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Head and Neck. 2008;30(9):1224–1230. doi: 10.1002/hed.20864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleisher KE, Welch G, Kottal S, Craig RG, Saxena D, Glickman RS. Predicting risk for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: CTX versus radiographic markers. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology and Endodontology. 2010;110(4):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van den Wyngaert T, Claeys T, Huizing MT, Vermorken JB, Fossion E. Initial experience with conservative treatment in cancer patients with osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and predictors of outcome. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20(2):331–336. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stockmann P, Vairaktaris E, Wehrhan F, et al. Osteotomy and primary wound closure in bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a prospective clinical study with 12 months follow-up. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2010;18(4):449–460. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adornato MC, Morcos I, Rozanski J. The treatment of bisphosphonateassociated osteonecrosis of the jaws with bone resection and autologous platelet-derived growth factors. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2007;138(7):971–977. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engroff SL, Kim DD. Treating bisphosphonate osteonecrosis of the jaws: is there a role for resection and vascularized reconstruction? Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2007;65(11):2374–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrari S, Bianchi B, Savi A, et al. Fibula free flap with endosseous implants for reconstructing a resected mandible in bisphosphonate osteonecrosis. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2008;66(5):999–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.06.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marx RE. Reconstruction of defects caused by bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2009;67(5):107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marx RE, Smith BR. An improved technique for development of the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1990;48(11):1168–1180. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migliorati CA, Epstein JB, Abt E, Berenson JR. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and bisphosphonates in cancer: a narrative review. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2011;7(1):34–42. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vescovi P, Merigo E, Meleti M, Fornaini C, Nammour S, Manfredi M. Nd:YAG laser biostimulation of bisphosphonate-associated necrosis of the jawbone with and without surgical treatment. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2007;45(8):628–632. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vescovi P, Merigo E, Fornaini C, et al. Thermal increase in the oral mucosa and in the jawbone during Nd:YAG laser applications. Ex vivo study. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17726. Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vescovi P, Manfredi M, Merigo E, et al. Surgical approach with Er: YAG laser on osteonecrosis of the jaws (ONJ) in patients under bisphosphonate therapy (BPT) Lasers in Medical Science. 2010;25(1):101–113. doi: 10.1007/s10103-009-0687-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vescovi P, Manfredi M, Merigo E, et al. Early surgical laser-assisted management of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ): a retrospective analysis of 101 treated sites with long-term follow-up. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery. 2012;30(1):5–13. doi: 10.1089/pho.2010.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vescovi P, Merigo E, Meleti M, et al. Bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a concise review of the literature and a report of a single-centre experience with 151 patients. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2012;41(3):214–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angiero F, Sannino C, Borloni R, Crippa R, Benedicenti S, Romanos GE. Osteonecrosis of the jaws caused by bisphosphonates: evaluation of a new therapeutic approach using the Er:YAG laser. Lasers in Medical Science. 2009;24(6):849–856. doi: 10.1007/s10103-009-0654-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atalay B, Yalcin S, Emes Y, et al. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis: laser-assisted surgical treatment or conventional surgery? Lasers in Medical Science. 2011;26(6):815–823. doi: 10.1007/s10103-011-0974-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stübinger S, Dissmann JP, Pinho NC, Saldamli B, Seitz O, Sader R. A preliminary report about treatment of bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaw with Er:YAG laser ablation. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2009;41(1):26–30. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scoletta M, Arduino PG, Reggio L, Dalmasso P, Mozzati M. Effect of low-level laser irradiation on bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws: preliminary results of a prospective study. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery. 2010;28(2):179–184. doi: 10.1089/pho.2009.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romeo U, Galanakis A, Marias C, et al. Observation of pain control in patients with bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis using low level laser therapy: preliminary results. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery. 2011;29(7):447–452. doi: 10.1089/pho.2010.2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vescovi P, Merigo E, Manfredi M, et al. Nd:YAG laser biostimulation in the treatment of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: clinical experience in 28 cases. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery. 2008;26(1):37–46. doi: 10.1089/pho.2007.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merigo E, Manfredi M, Meleti M, et al. Bone necrosis of the jaws associated with bisphosphonate treatment: a report of twenty-nine cases. Acta Biomedica de l’Ateneo Parmense. 2006;77(2):109–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]