Abstract

Antihistamines are one of the most common drugs that are used extensively in various dermatological and nondermatological conditions. The use of H-1-antihistamines during pregnancy has been very controversial due to possible teratogenic effects of these drugs. None of the antihistamines available today have been categorized as safe during pregnancy. Control studies are available for certain first generation drugs regarding their safety in pregnancy, but the newer agents require further studies to be declared safer in pregnancy. A few drugs are comparatively safer to use in pregnancy than others. Every drug used in pregnancy carries a risk for teratogenicity and careful risk/benefit assessment should be done before prescribing them.

Keywords: Gestation, histamine antagonist, teratogenicity

INTRODUCTION

Pruritus is one of the most common dermatological symptoms in pregnancy.[1] Pruritus in pregnancy has always been challenging to the treating physician both in diagnosis and treatment. Pruritus occurs due to various causes, and it can occur any time during pregnancy. Causes for pruritus in pregnancy are numerous ranging from specific dermatoses of pregnancy to various dermatological conditions such as atopic dermatitis, urticarial, infections, and infestations or drug induced. In addition to these, various systemic diseases can also manifest with pruritus. Other than itching antihistamines are also used for various allergic diseases and also used for emesis during pregnancy. Allergies can occur in about 20–30% of women during pregnancy.[2]

Any drug taken during the pregnancy has a potential teratogenic effect on the fetus. If a drug is consumed during the first trimester, it can result in severe structural fetal malformations and in the later part of pregnancy it can result in various functional defects or growth disorders and can also lead to minor malformations. Drugs taken during the pregnancy can also lead to after effects in the neonatal and infancy period. All pharmacological interventions are generally avoided during pregnancy due to the alarming information present in the patient information leaflet and also on the drug envelopes. The physician has to weigh the benefits of the treatment against the potential teratogenic effects before using any drug during pregnancy.

Among the drugs prescribed during pregnancy, antihistamines are one of the commonest, either as an antipruritic agent or an antiemetic agent.[3] Many a times the patient procures these agents as an over the counter preparation and uses it. Various studies on the use of antihistamines (H1 blockers) during pregnancy, including a meta-analysis of more than 200,000 women shows no increase in the teratogenic risk of these drugs in the humans.[3–6] Certain animal studies with hydroxyzine, cyclizine, and promethazine have shown teratogenic effects, but no human teratogenicity reports have so far been reported. Drugs such as dexchlorpheniramine and alimemazine (trimeprazine) were not found to have any teratogenic effect even in animal studies. None of the antihistamines has been so far declared safe during the pregnancy by FDA on the basis of controlled animal or human studies.[7] Isolated reports of antihistamines causing congenital malformations have been reported, but they warrant further investigations and interpretation.[6,8,9]

Classification of antihistamines

h1-antihistamines are classified into the first generation sedating antihistamines and the second generation nonsedating antihistamines.

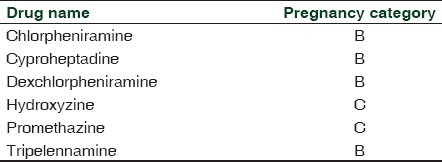

The first generation antihistamines include drugs such as diphenhydramine, cyproheptadine, promethazine, chlorpheniramine, and hydroxyzine. They have a very potent effect with high lipophilicity but are short acting. They are metabolized in the liver by the microsomal cytochrome P-450 system. The common side effects of this category of antihistamines include sedation and anticholinergic effects—dryness of the mouth, blurring of vision, constipation and urinary retention. FDA has categorized the first generation antihistamines according to the pregnancy complications [Table 1].[10] Promethazine and hydroxyzine have been categorized as pregnancy category C due to lack of well-controlled studies in human being. Michigan Medicaid Birth Defects study has linked hydroxyzine to cleft palate in new borns.[11]

Table 1.

FDA pregnancy category classification for the first-generation antihistamines

Pregnancy category B means the drug has failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in animal reproduction studies and there is a lack of well-controlled studies in pregnant women or animal studies have shown an adverse effect, but adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in any trimester. Pregnancy category C means that animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans, but potential benefits may warrant the use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks.

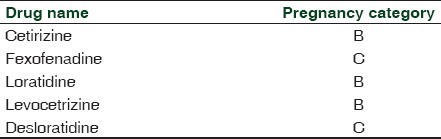

The second generation antihistamines include drugs such as loratadine, fexofenadine, cetirizine, and azelastine. They have a high therapeutic index, with highly selective actions and are nonsedating. They are long acting, but are poorly lipophilic and hence have no entry to the central nervous system. Side effects of the second generation antihistamines include photosensitivity, tachycardia, and prolongation of the Q–T interval. FDA has categorized the second generation antihistamines as shown in [Table 2]. Fexofendine and desloratidine have been classified as pregnancy category C. Reduction in pup weight and survival were observed with fexofenadine. There are no human data on fexofenadine and loratadine for them to be categorized as safe during pregnancy. Loratadine had previously been proposed as a possible factor for the increased incidence of hypospadiasis in infants born to mothers who had taken loratadine during pregnancy.[12] However, recent studies have ruled out this possibility and suggest that this agent does not represent a major teratogenic risk.[13,14] However, loratadine is still considered as a category B drug by FDA.

Table 2.

FDA pregnancy category classification for second-generation antihistamines[10]

Safety of antihistamines during pregnancy

Although pruritus is not a life-threatening medical condition, it can be extremely troublesome for pregnant women. Because of potential effects on the fetus, the treatment of pruritus in pregnancy requires prudent consideration. At one point, the physician will have to use the antihistamines and weigh the benefits against the teratogenic effects of the antihistamines. Physicians must decide whether to select an older, better-studied antihistamine, thought to be relatively safe during pregnancy, or a newer agent that has less adverse effect on quality of life but has a potential teratogenic effect.[9]

Various recommendations and studies favor the use of first generation antihistamines for use during pregnancy.[15] They point out that these antihistamines were in use for a longer period of time and were more widely used during pregnancy. More data are available about the various effects of the first generation antihistamines in pregnancy.[16,17] Moreover a few of the second generation agents have been reported to be associated with an increased incidence of certain congenital malformations.[13]

In 1993, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) Working Group on Asthma and Pregnancy recommended the first-generation agents chlorpheniramine and tripelennamine as the antihistamines of choice during pregnancy, based on duration of availability as well as reassuring animal and human data.[18]

The Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines, published in 2001, concluded that the older antihistamines have an overall unfavorable risk/benefit ratio, even in the nonpregnant population, because of their poor selectivity and their sedative and anticholinergic effects.[19] ARIA recommends that where possible, first-generation antihistamines should no longer be prescribed. In general, second-generation antihistamines are more potent, have a longer duration of action, and produce minimal sedation.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and The American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) have recommended chlorpheniramine and tripelennamine as the antihistamines of choice for pregnant women.[20] They also recommend cetirizine and loratadine after the first trimester in patients who cannot tolerate or do not respond to maximal doses of chlorpheniramine or tripelennamine.

Other studies suggest that there is insufficient evidence to support the first-line use of cetirizine and loratadine during pregnancy and recommend first considering chlorpheniramine, tripelennamine, or hydroxyzine if an antihistamine is needed during pregnancy.[21]

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In every pregnant case with pruritus the basic cause of pruritus should first be sought out before starting the antihistamines. Appropriate investigations should also be done. Before any medication is taken during pregnancy, the doctor and patient should have a risk/benefit discussion. The patient should be explained the fact that though no definite teratogenic effects have been reported to be associated with the intake of antihistamines in pregnancy, they are not licensed by the FDA as category A or the safe group. Also it is important to mention that in India no definitive guidelines have been given or followed by the government to prevent the use of H1-antihistamines as over the counter medicines. Even for prescription purposes, no definitive guidelines have been given by the government and practitioners generally follow the FDA criteria.

If possible the pruritus and other allergic manifestations in the first trimester of pregnancy should be managed using topical medications like bland emollients and systemic antihistamines should be avoided as none of the antihistamines are categorized as safe by the FDA and in India no specific guidelines exist regarding their use in pregnancy.[10] Preferably all drug usage including antihistamines should be deferred in the first trimester. If antihistamines have to be prescribed then first generation agents should be preferred and among them chlorpheniramine, dexchlorpheniramine and hydroxyzine should be the first choice of agents. The patient should also be advised to drink plenty of water when taking antihistamines during pregnancy to overcome the anticholinergic side effects. They should also be advised to take immediate gynecological consultation if they find any change in the frequency of baby's movement or increased contractions after taking the drugs.

If a second generation agent has to be used then loratadine or cetirizine should be preferred as they have been widely studied for possible teratogenic effects and have been found to be nonteratogenic till date. Both these agents are pregnancy category B agents. Second generation agents are preferably used after the first trimester if it has to be and preferably avoided in the early pregnancy when organogenesis takes place.

To conclude first generation antihistamines such as chlorpheniramine, hydroxyzine, and dexchlorpheniramine are the safest among antihistamines to be used in pregnancy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black MM, McKay M, Braude PR. Color atlas and text of obstetric and gynecologic dermatology. 2nd ed. London: Times Mirror International Publishers Limited; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keleş N. Treatment of allergic rhinitis during pregnancy. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18:23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephansson O, Granath F, Svensson T, Haglund B, Ekbom A, Kieler H. Drug use during pregnancy in Sweden - assessed by the Prescribed Drug Register and the Medical Birth Register. Clin Epidemiol. 2011;3:43–50. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S16305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seto A, Einarson T, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome following first trimester exposure to antihistamines: meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol. 1997;14:119–24. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber-Schoendorfer C, Schaefer C. The safety of cetirizine during pregnancy. A prospective observational cohort study. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;26:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85:137–50. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lis-Swiety AD, Brzezinska-Wcislo LA. [The safety of the antihistamines in dermatoses of pregnancy] Wiad Lek. 2006;59:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kallen B. Use of antihistamine drugs in early pregnancy and delivery outcome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:146–52. doi: 10.1080/jmf.11.3.146.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schatz M. H1-antihistamines in pregnancy and lactation. Clin Allergy Immunol. 2002;17:421–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meadows M. FDA Consumer Magazine. Washington, D.C: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2001. May-Jun. Pregnancy and the drug dilemma. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang Y, Ma CX, Cui W, Chang V, Ariet M, Morse SB, et al. The risk of birth defects in multiple births: a population-based study. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedersen L, Norgaard M, Skriver MV, Olsen J, Sorensen HT. Prenatal exposure to loratadine in children with hypospadias: a nested case-control study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Am J Ther. 2006;13:320–4. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200607000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Aharonovich A, Moerman L, Arnon J, Wajnberg R, et al. Pregnancy outcome after gestational exposure to loratadine or antihistamines: a prospective controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1239–43. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Evaluation of an association between loratadine and hypospadias United States, 1997-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:219–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.So M, Bozzo P, Inoue M, Einarson A. Safety of antihistamines during pregnancy and lactation. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:427–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buhimschi CS, Weiner CP. Medications in pregnancy and lactation: Part 2. Drugs with minimal or unknown human teratogenic effect. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:417–32. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818d686c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert C, Mazzotta P, Loebstein R, Koren G. Fetal safety of drugs used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis: a critical review. Drug Saf. 2005;28:707–19. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NAEPP Report of the Working Group on Asthma and Pregnancy: Management of Asthma During Pregnancy. NIH Publication No. 93-3279. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; National Institutes of Health; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1993. [Accessed May 11, 2011]. Asthma and Pregnancy Report. Available from URL: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/lung/ asthma/astpreg.txt . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N Aria Workshop Group. World Health Organization. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5 Suppl):S147–334. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The use of newer asthma and allergy medications during pregnancy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and The American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;84:475–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert C, Mazzotta P, Loebstein R, Koren G. Fetal safety of drugs used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis: a critical review. Drug Saf. 2005;28:707–19. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]