Abstract

In Alzheimer disease (AD) patient brains, the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides is associated with activated microglia. Aβ is derived from the amyloid precursor protein; two major forms of Aβ, that is, Aβ1-40 (Aβ40) and Aβ1-42 (Aβ42), exist. We previously reported that rat microglia phagocytose Aβ42, and high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1), a chromosomal protein, inhibits phagocytosis. In the present study, we investigated the effects of exogenous HMGB1 on rat microglial Aβ40 phagocytosis. In the presence of exogenous HMGB1, Aβ40 markedly increased in microglial cytoplasm, and the reduction of extracellular Aβ40 was inhibited. During this period, HMGB1 was colocalized with Aβ40 in the cytoplasm. Furthermore, exogenous HMGB1 inhibited the degradation of Aβ40 induced by the rat microglial cytosolic fraction. Thus, extracellular HMGB1 may internalize with Aβ40 in the microglial cytoplasm and inhibit Aβ40 degradation by microglia. This may subsequently delay Aβ40 clearance. We further confirmed that in AD brains, the parts of senile plaques surrounded by activated microglia are composed of Aβ40, and extracellular HMGB1 is deposited on these plaques. Taken together, microglial Aβ phagocytosis dysfunction may be caused by HMGB1 that accumulates extracellularly on Aβ plaques, and it may be critically involved in the pathological progression of AD.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and loss of synapses and neurons in particular brain areas [1]. Experimental studies using transgenic AD mouse models have demonstrated that Aβ accelerates NFT formation [2, 3] and is closely associated with synaptic damage [4]. In contrast, Aβ reduction in the brain by Aβ immunization restores cognitive functions in transgenic AD mouse models [5–9] and also appears to slow cognitive decline in human AD patients [10]. Thus, the accumulation of Aβ may play a key role in the pathogenesis of AD [11].

Aβ is derived from the sequential proteolysis of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases and is composed of 37–43 amino acid residues because γ-secretase, which is a protein complex including presenilin (PS), generates the C-terminal of Aβ with different lengths [12]. Among the variations in Aβ, Aβ1-40 (Aβ40) and Aβ1-42 (Aβ42) are the major species found in AD brains. The most predominant species deposited in Aβ plaques is Aβ42 [13], which is prone to aggregation [14] and indicates increased neurotoxicity [15]. On the other hand, Aβ40 is the major soluble species; its secretion is 10-fold more than that of Aβ42 in normal brains. A previous study demonstrated that the deposition of Aβ40 in AD brains is particularly correlated with synaptic and neuronal loss [16]. Thus, lowering the concentration of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the brain may serve as a disease-modifying therapy for AD patients.

Activated microglia accumulate on Aβ plaques in AD brains. Although microglial accumulation was initially believed to be involved in the formation of Aβ plaques [17], experimental studies later demonstrated the ability of microglia to phagocytose Aβ peptides [18, 19]. In addition, we demonstrated microglial contribution in Aβ42 clearance using primary cultured rat microglia [20–25]. However, it has been reported that microglial dystrophy occurs in aging human brains [26], and the age-related disability of microglial Aβ phagocytosis has been demonstrated experimentally [27]. Thus, the dysfunction of microglial Aβ phagocytosis appears to be closely involved in the progression of AD pathology.

High-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) is an abundant nonhistone chromosomal protein that is released from cells undergoing necrosis [28, 29]. The released HMGB1 behaves like an inflammatory mediator by acting on receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 2 and 4 [30, 31]. We have previously reported that HMGB1 is extracellularly associated with Aβ plaques in AD brain and is involved in the pathogenesis of AD as an inhibitory factor against microglial Aβ42 phagocytosis by interfering with uptake [32, 33]. However, the effect of extracellular HMGB1 on the microglial phagocytosis of Aβ40, but not Aβ42, has not been elucidated. Therefore, in the present study, we analyzed rat microglial Aβ40 phagocytosis in the presence and absence of exogenous HMGB1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primary Culture of Rat Microglia and Drug Treatment

The primary culture experimental procedure was reviewed and approved by the Committee for Animal Research at Kyoto Pharmaceutical University. Primary cultured microglia (over 97% pure) were prepared, as described previously [32]. Briefly, brain tissues were isolated from newborn Wistar rats, minced, and gently dissociated by trituration in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM). The tissue suspension was filtered through a 50 μm diameter nylon mesh into 50 mL tubes, and cells were collected by centrifugation at 200 ×g for 10 min. Cells were resuspended in DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin; they were then plated onto 100 mm diameter dishes at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2/95% air. We then harvested the floating microglia from mixed glial cultures. Microglia were transferred to 24-well plates (3.0 × 105 cells/well) and were allowed to adhere at 37°C overnight; they were then treated with sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as the vehicle or synthetic human Aβs (Aβ40 or Aβ42; Anaspec, San Jose, CA) in the presence or absence of calf thymus-purified HMGB1 (WAKO Chemicals, Osaka, Japan). We previously demonstrated that 1 μM Aβ42 for 12 h markedly phagocytosed by rat microglia [20], and 0.3 μM HMGB1 inhibits the phagocytosis [32, 33]. When Aβ40 at 1–3 μM were added into the culture, we could detect Aβ40 phagocytosed by rat microglia by Western blot analysis [25]. Therefore, in the present study, we adopted the concentrations at 1 μM and 0.3 μM for the treatments with Aβs and HMGB1, respectively. To make the experimental conditions more accurate, we dissolved the lyophilized human Aβ peptides in distilled and sterilized water at a high concentration, and small aliquots were kept at −80°C until use. Subsequently, Aβ stock solutions were diluted using sterilized PBS, and once Aβ was thawed, no Aβ was refrozen to eliminate variance due to repeated freezing and thawing.

2.2. Immunocytochemistry

Twelve hours after Aβ treatment, microglia were gently rinsed three times with PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM phosphate buffer (PB) for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against Aβ (clone 6E10, 1 : 1000; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against HMGB1 (1 : 1000; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). The primary antibodies were followed by application of a rhodamine-labeled anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody (each diluted 1 : 500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Furthermore, cells were incubated with Hoechst 33258 (1 : 5000; Molecular Probes) to visualize microglial nuclei. Labeled fluorescence was detected using a laser scanning confocal microscope LSM 510 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

2.3. Aβ Phagocytosis and Clearance Assay by Western Blot Analysis

Twelve hours after Aβ treatment, microglia and culture media were collected and lysed with Laemmli's sample buffer and then analyzed by Western blot analysis. Briefly, samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 20% polyacrylamide gels in Tricine buffer). Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA) by electroelution and then incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against Aβ (clone 6E10, 1 : 2000; Chemicon), followed by a horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody against mouse IgG (1 : 1,000; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). Subsequently, protein bands were detected on radiographic films (Kodak, Rochester, NY) using a chemiluminescence kit (ECL kit; Amersham). For semiquantitative analysis, radiographic films were scanned with a CCD color scanner (DuoScan, AGFA, Mortsel, Belgium) and then analyzed densitometrically using the public domain US National Institutes of Health image 1.56 program.

2.4. Aβ Degradation Assay

Microglia were harvested and resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT and then homogenized. After centrifugation (50,000 ×g) for 20 min at 4°C, the protein concentration of the supernatant was measured and used as the microglial cytosolic fraction. The Aβ peptide (3 μM Aβ40 or Aβ42) was incubated with the microglial cytosolic fraction (final concentration of 1 mg/mL) in the presence or absence of 0.3 μM HMGB1. At the time points of 0, 6, and 12 h after incubation, Laemmli's sample buffer was added, and samples were boiled at 100°C for 5 min to stop Aβ degradation. Subsequently, samples were analyzed using the antibody against Aβ (clone 6E10, 1 : 2000; Chemicon) by Western blot analysis, as described previously.

2.5. Immunoprecipitation

HMGB1 (1.5 μg, 2.6 μM) was mixed with 3 μg of synthetic Aβ40 (37.5 μM) in PBS. Twenty-four hours after incubation, the antibody (10 μg of IgG) against HMGB1 (BD Pharmingen) or Aβ (clone 6E10; Chemicon) was added to the mixture and further incubated for 2 h at 4°C. Protein A-Sepharose (50 μL of a 50% slurry) was then added, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation, immunoprecipitates were resuspended in Laemmli's sample buffer. Subsequently, samples were analyzed using the antibody against HMGB1 (1 : 1000; BD Pharmingen) or Aβ (clone 6E10, 1 : 2000; Chemicon) by Western blot analysis, as described previously.

2.6. Immunohistochemical Study Using Human AD Brain Sections

All experiments using human samples were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the ethical committees of Kyoto Pharmaceutical University. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. For histological examination, frontal cortex tissue from a patient who was clinically and histopathologically diagnosed as human AD (age, 67 years) was used. Neuropathological assessment of AD was conducted in accordance with the criteria of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Dissected tissue blocks were fixed in 10% formalin and transferred to a 15% sucrose solution in 100 mM PB containing 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C. The cryoprotected brain blocks were cut into 20 μm sections on a cryostat, and the collected sections were stored in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBS-T) and 0.1% sodium azide at 4°C until use.

Immunohistochemical study was essentially performed as described previously [34]. Free-floating human brain sections were treated with 0.1% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min to quench endogenous peroxidase activity; they were then incubated with 1% goat serum to block nonspecific binding in PBS. Sections were then incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against Aβ40 (1 : 1000; nanoTools, Teningen, Germany) and rabbit polyclonal antibody against Aβ42 (1 : 1000; IBL, Gunma, Japan), a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Aβ40 (1 : 1000; IBL) and mouse monoclonal antibody against human leukemia antigen (HLA)-DR (1 : 50; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), or a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Aβ42 (1 : 1000; IBL) and mouse monoclonal antibody against HLA-DR (1 : 50; Dako) in PBS-T with 0.1% sodium azide for 4 days at 4°C. After washing with PBS-T, the sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1 : 2000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with avidin peroxidase (1 : 4000; ABC Elite Kit; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, labeling was visualized by incubation with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 0.02% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and 0.0045% hydrogen peroxide with nickel enhancement using 0.6% nickel ammonium sulfate, which yielded a dark blue color. In the second cycle, sections were incubated with a biotinylated anti-mouse IgG antibody (1 : 2000; Vector Laboratories) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with avidin peroxidase (1 : 4000; ABC Elite Kit; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the DAB reaction was performed without nickel ammonium sulfate, which yielded a brown color.

In laser confocal microscopic analysis, human AD brain sections were treated with 1% goat serum to block nonspecific binding in PBS. Sections were then coincubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Aβ40 (1 : 1000; IBL) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against HLA-DR (1 : 50; Dako) or a mouse monoclonal antibody against Aβ40 (1 : 1000; nanoTools) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against HMGB1 (1 : 1000; BD Pharmingen) in PBS-T with 0.1% sodium azide for 4 days at 4°C. The primary antibodies were probed with Alexa Fluor 546-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody and Alexia Fluor 488-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody or Alexa Fluor 546-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody and Alexia Fluor 488-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody (each diluted 1 : 500; Molecular Probes). Subsequently, fluorescence was observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope LSM 510 (Carl Zeiss).

2.7. Statistical Evaluation

Results of the densitometric analysis are given as the mean ± standard error of mean. The statistical significance of differences was determined by analysis of variance. Further statistical analysis for post hoc comparisons was conducted using the Bonferroni/Dunn test (StatView, Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).

3. Results

3.1. Binding of HMGB1 with Aβ40

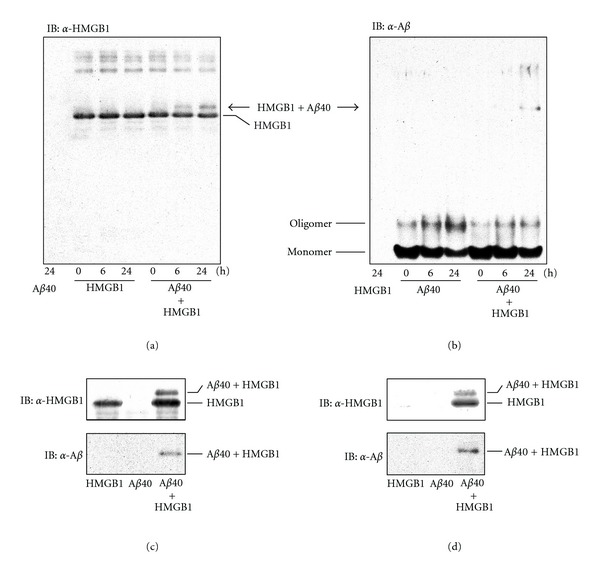

In our previous study, we found that HMGB1 is extracellularly accumulated on Aβ plaques in AD brains and further demonstrated that HMGB1 binds to Aβ42 in in vitro cell-free study [33]. In the present cell-free study, we first examined the binding affinity of HMGB1 for Aβ40. Following incubation of the HMGB1 peptide alone, a 29 kDa band of HMGB1 and its high-molecular-weight aggregates was detected, while an approximately 33 kDa band (arrow in Figure 1(a)), which is believed to be a complex of HMGB1 and Aβ40, appeared as an upper band 6 h after incubation of HMGB1 and Aβ40 peptides (Figure 1(a)). Following incubation with Aβ40 (Figure 1(b)), monomers and oligomers of Aβ40 were the major components present in the absence of HMGB1 at each time point. Predictably, the 33 kDa band, which seemed to be a complex of HMGB1 and Aβ40, was detected by the addition of the HMGB1 peptide (arrow in Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Binding affinity of HMGB1 for Aβ40. (a, b) After incubation of HMGB1, Aβ40, and the mixture of HMGB1 with Aβ40 for 0, 6, and 24 h, samples were analyzed by Western blot analysis using the anti-HMGB1 antibody (a) or anti-Aβ antibody (b). (c, d) After incubation of HMGB1, Aβ40, and the mixture of HMGB with Aβ40 for 24 h, samples were immunoprecipitated using the anti-HMGB1 antibody (c) or anti-Aβ antibody (d). The precipitates were then analyzed by Western blot analysis using the anti-HMGB1 antibody and anti-Aβ antibody.

To confirm the binding affinity between HMGB1 and Aβ40, we further examined immunoprecipitation using the anti-HMGB1 antibody (Figure 1(c)) or anti-Aβ antibody (Figure 1(d)). As a result, in the mixture of HMGB1 and Aβ, the complex of HMGB1 and Aβ40 (approximately 33 kDa) was immunoprecipitated with A-Sepharose-linked antibodies against HMGB1 (Figure 1(c)) or Aβ (Figure 1(d)). These results demonstrated that HMGB1 had a binding affinity for Aβ40.

3.2. Microglial Aβ Phagocytosis and Effect of Exogenous HMGB1

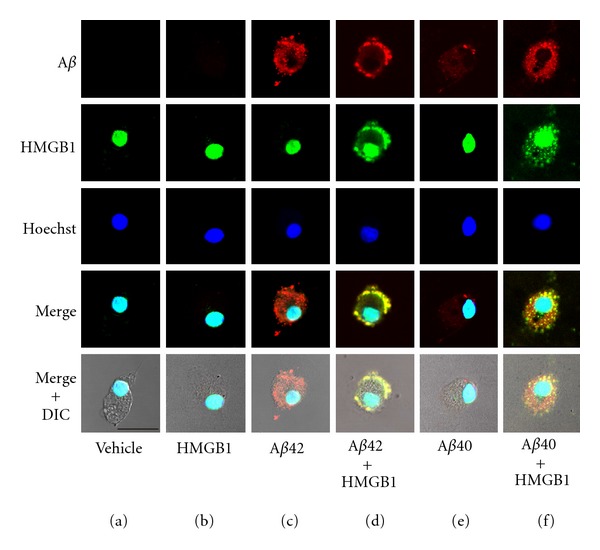

We previously demonstrated that microglia markedly phagocytose Aβ42 [25], and extracellular HMGB1 inhibits phagocytosis on the cell surface [32, 33]. In the present study, we analyzed the microglial Aβ40 phagocytosis and the effects of extracellular HMGB1 on phagocytosis using laser confocal microscopy (Figure 2). Endogenous HMGB1 was detected in the nuclei of primary cultured rat microglia (Figures 2(a)–2(f), cyan). When treated with the vehicle (Figure 2(a)) or HMGB1 alone (Figure 2(b)), no Aβ immunoreactivity was detected. Consistent with previous studies, in the presence of Aβ42, microglia phagocytosed Aβ42 (Figure 2(c), red), exogenous HMGB1 was colocalized with Aβ42 on the microglial cell surface, and Aβ internalization was inhibited (Figure 2(d), yellow). When treated with Aβ40, the immunoreactivity of Aβ40 was barely detected in the microglial cytoplasm (Figure 2(e), red). Interestingly, in the presence of exogenous HMGB1, small vesicle-like immunoreactivities of Aβ40 (Figure 2(f), red) and HMGB1 (Figure 2(f), green) were markedly increased in the microglial cytoplasm, and parts of them were colocalized with each other (Figure 2(f), yellow).

Figure 2.

Effect of exogenous HMGB1 on microglial Aβ phagocytosis analyzed by laser confocal microscopy. Rat microglia were incubated with the vehicle (a), HMGB1 (b), Aβ42 (c), Aβ42 and HMGB1 (d), Aβ40 (e), or Aβ40 and HMGB1 (f) for 12 h. Fixed cells were further incubated with the anti-Aβ antibody (red), anti-HMGB1 antibody (green), and Hoechst 33258 (dye for nuclei; blue); they were analyzed using a laser scanning confocal microscope. DIC: differential interference contrast. Scale bar = 20 μm for all panels.

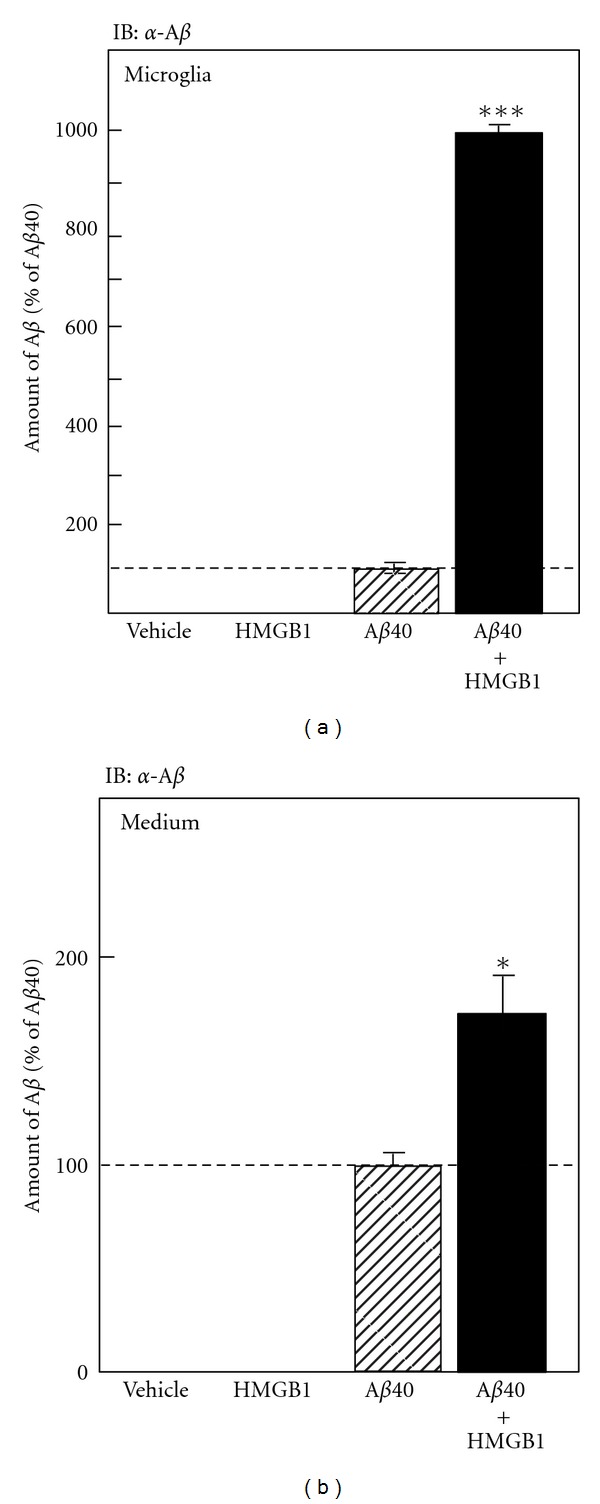

3.3. Amounts of Aβ40 inside and outside Microglia and Effect of Exogenous HMGB1

Twelve hours after Aβ40 treatment, microglial cell lysate and conditioned medium were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis; semiquantitative analysis was then examined to measure the concentration of Aβ40 inside (Figure 3(a)) and outside microglia (Figure 3(b)). When microglia were treated with the vehicle or exogenous HMGB1 alone, no Aβ40 immunoreactivity was detected inside them (Figure 3(a)). After treatment with Aβ40, a small amount of Aβ40 was detected inside microglia (Aβ40 phagocytosed by microglia), and this amount increased dramatically by simultaneous treatment with exogenous HMGB1 (Figure 3(a)). This result raises two possibilities: (i) extracellular HMGB1 increases microglial Aβ40 uptake, and (ii) HMGB1 inhibits the degradation of Aβ40 in the microglial cytoplasm after uptake. To address these possibilities, we measured the amount of Aβ40 in the culture medium (Aβ40 remaining outside microglia) (Figure 3(b)). After treatment with the vehicle or exogenous HMGB1 alone, no Aβ was detected in the culture medium. Twelve hours after Aβ40 treatment, the amount of Aβ40 in the culture medium significantly increased by simultaneous treatment with exogenous HMGB1. Thus, in the presence of exogenous HMGB1, the amount of Aβ40 both inside and outside microglia was much higher than that when treated with Aβ40 alone. These results suggest that exogenous HMGB1 phagocytosed by microglia inhibits the degradation of Aβ40 in the microglial cytoplasm and subsequently delays Aβ clearance by microglia.

Figure 3.

Effect of exogenous HMGB1 on microglial Aβ phagocytosis analyzed by Western blot. Rat microglia were incubated with the vehicle, HMGB1, Aβ40, or Aβ40 and HMGB1 for 12 h. Microglial cell lysate (a) and conditioned medium (b) were then subjected to Western blot analysis using the anti-Aβ antibody, and then the amounts of Aβ40 inside (a) and outside microglia (b) were semiquantitatively measured. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 versus treatment with Aβ40 alone.

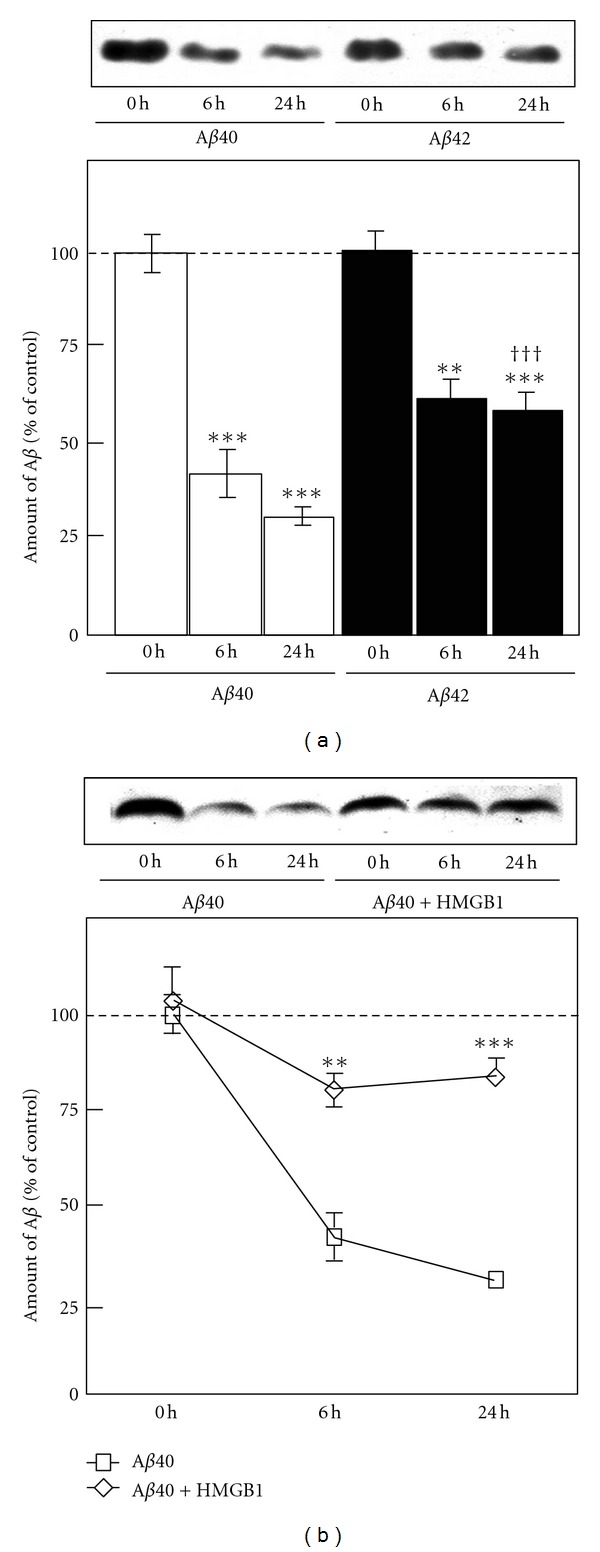

3.4. Aβ Degradation with the Microglial Cytosol Fraction and Effect of Exogenous HMGB1

To confirm whether exogenous HMGB1 inhibits Aβ40 degradation in microglial cytoplasm, we prepared cytosolic fractions from rat microglia and mixed them with Aβ. Degradation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 by microglial cytosol fractions was compared (Figure 4(a)). Aβ40 and Aβ42 were gradually degraded by the addition of the microglial cytosolic fraction in a time-dependent manner. Aβ40 was degraded earlier than Aβ42 (Figure 4(a)). We next examined the effect of exogenous HMGB1 on the Aβ40 degradation induced by the microglial cytosolic fraction (Figure 4(b)). At 6 and 24 h after incubation, the degradation of Aβ40 was significantly delayed by the addition of exogenous HMGB1. Thus, this result suggests that exogenous HMGB1 phagocytosed by microglia inhibits the degradation of Aβ40 in the microglial cytoplasm.

Figure 4.

Aβ degradation with the microglial cytosolic fraction. (a) Aβ40 and Aβ42 were incubated with the rat microglial cytosolic fraction for 0, 6, and 24 h. After incubation, samples were subjected to Western blot analysis using the anti-Aβ antibody, and the amount of Aβ was semiquantitatively measured. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus time point 0 h. ††† P < 0.001 versus Aβ40 at time point 24 h. (b) Aβ40 and Aβ40 with HMGB1 were incubated with rat microglial cytosolic fractions for 0, 6, and 24 h. After incubation, the samples were subjected to Western blot analysis using the anti-Aβ antibody, and the amount of Aβ was semiquantitatively measured. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus Aβ40 alone at each time point.

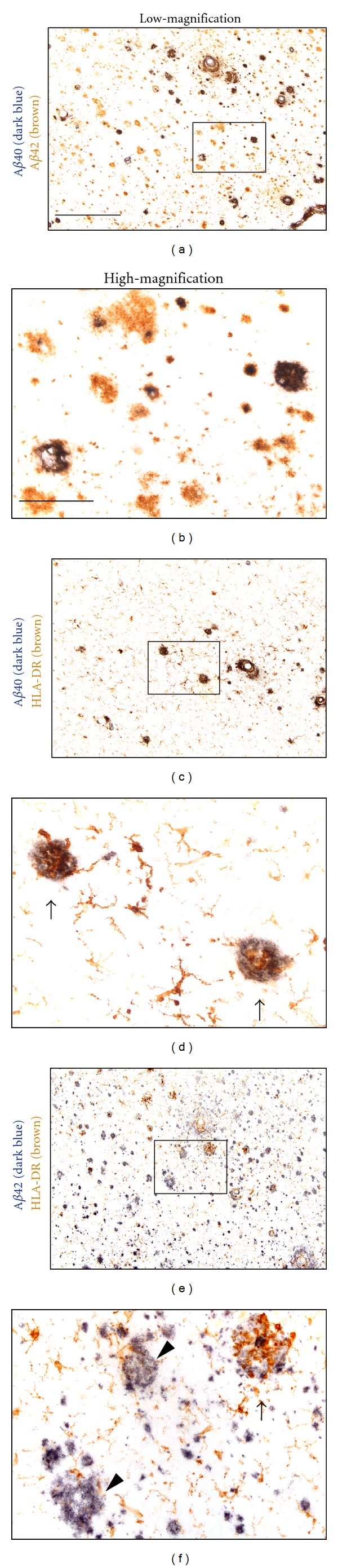

3.5. Accumulation of Aβ40, Aβ42, and Microglia in AD Brains

We further investigated the localization of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in AD brains using specific antibodies (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)) and microglial accumulation on the plaques composed of Aβ40 (Figures 5(c) and 5(d)) and Aβ42 (Figures 5(e) and 5(f)). The number of Aβ40 plaques (dark blue deposits in Figure 5(a)) was lesser than that of Aβ42 plaques (brown deposits in Figure 5(a)). High-magnification photographs revealed that Aβ40 accumulated on Aβ42 plaques (Figure 5(b)). Regarding microglial accumulations (Figures 5(c)–5(f)), almost all Aβ40 plaques were markedly surrounded by activated microglia (Figure 5(c) and arrows in Figure 5(d)). Although some Aβ42 plaques were markedly accumulated by microglia (Figure 5(e) and arrow in Figure 5(f)), others were moderately or poorly surrounded by microglia (arrowheads in Figure 5(f)).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical study of microglial accumulation on Aβ plaques in human AD brains. Free-floating human AD brain sections were incubated with the anti-Aβ40 specific antibody (dark blue) and anti-Aβ42 specific antibody (brown) (a, b), anti-Aβ40 specific antibody (dark blue) and anti-HLA-DR antibody (for microglial staining; brown) (c, d), and anti-Aβ42 specific antibody (dark blue) and anti-HLA-DR antibody (for microglial staining; brown). Arrows and arrow heads show marked and poor microglial accumulations, respectively. (b), (d), and (f) show high-magnification views of squared area in (a), (c), and (e), respectively. Scale bar in (a) equals 400 μm for (a), (c), and (e). Scale bar in (b) equals 100 μm for (b), (d), and (f).

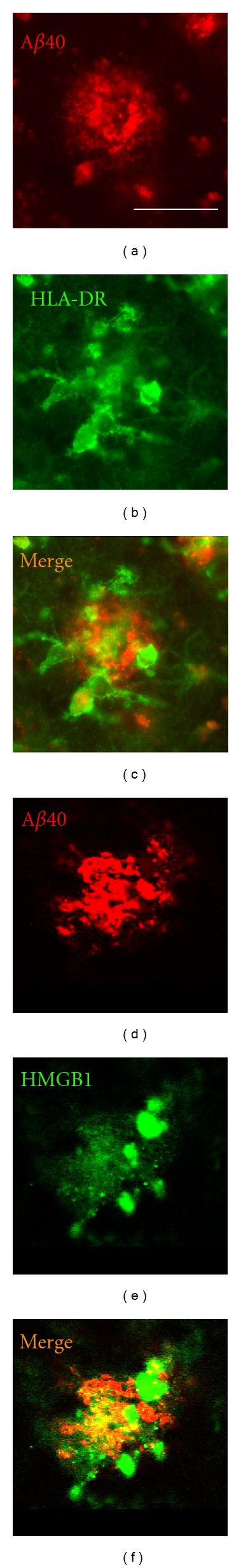

3.6. Accumulation of HMGB1 and Microglia on Aβ40 Plaques in AD Brains

We previously demonstrated that extracellular HMGB1 accumulates on Aβ plaques, as detected using an anti-Aβ antibody that reacts with a broad spectrum of Aβ species [33]. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the colocalization of extracellular HMGB1 on Aβ40 plaques in AD brains using a specific anti-Aβ40 antibody. Consistent with the immunohistochemical study (Figures 5(c) and 5(d)), microglia (Figure 6(b)) markedly accumulated on Aβ40 plaques (Figure 6(a)) in AD brains (Figure 6(c)). We further demonstrated that extracellular HMGB1 (Figure 6(e)) colocalized with Aβ40 plaques (Figure 6(d)) in AD brains (Figure 6(f)).

Figure 6.

Laser confocal microscopic study on the accumulation of HMGB1 and microglia on Aβ40 plaques in human AD brains. (a–c) Free-floating human AD brain sections were incubated with the anti-Aβ40 specific antibody ((a) red) and anti-HLA-DR antibody ((b) for microglial staining, green). The merged image is indicated in (c). (d–f) Free-floating human AD brain sections were incubated with the anti-Aβ40 specific antibody ((a); red) and anti-HMGB1 antibody ((b); green). The merged image is indicated in (f). Scale bar in (a) equals 50 μm for all panels.

4. Discussion

In studies on familial AD, mutations in the APP, PS1, and PS2 genes have been detected, and transgenic mice models carrying these familial AD-linked mutations show enhanced Aβ production in their brains. In particular, transgenic mice carrying the APP mutation display characteristics that closely resemble AD, such as Aβ deposition and memory dysfunction [35, 36], and introduction of the double mutations of PS/APP exhibits the early onset of these pathologies [37]. Thus, all mutations are involved in Aβ generation, and the accumulation of Aβ in the brain has been strongly suggested to be the primary event driving the pathogenesis of AD. However, familial AD accounts for less than 1% of all AD cases [38]; most cases develop sporadically. Although the etiology of sporadic AD remains much more elusive than that of familial cases, neurological and pathological events in sporadic AD are essentially indistinguishable from those in familial cases. In sporadic AD, a decreased Aβ clearance rate has been reported [39].

One proposed mechanism of Aβ clearance is microglial Aβ phagocytosis [40, 41]. Reports on AD patients treated with Aβ immunization also indicate microglial contribution to Aβ clearance in human AD brains [42, 43]. However, it has been suggested that the ability of microglia to clear Aβ decreases with age and progression of AD pathology [26, 27], and it may, at least in part, account for the dysregulation of Aβ clearance in sporadic AD.

HMGB1 inhibits microglial Aβ42 phagocytosis by interfering with Aβ42 internalization [32, 33]. In the present study, we further showed that exogenous HMGB1 inhibits the degradation of Aβ40 in rat microglial cytoplasm and subsequently delays Aβ40 clearance. We demonstrated the binding affinities of HMGB1 for Aβ40 and Aβ42 [33]. Aβ contains an amino acid sequence (18VFFA21) that has been identified to be essential for aggregation and fibril formation [44]. Interestingly, HMGB1 contains a homologous motif (16AFFV19), and this sequence is thought to be critically involved in the interactions of Aβ with HMGB1 [33, 45]. Among the many peptidases that have been proposed as Aβ-degrading enzymes [46], insulin-degrading enzyme, cathepsin D, and neprilysin are the principle enzymes involved in microglia-mediated Aβ degradation [25, 47, 48]. Many cleavage sites that are the targets of microglial Aβ-degrading enzymes are located on and in the vicinity of the amino acid sequence (18VFFA21) of Aβ [46]. Therefore, we speculate that the cleavage sites of Aβ are masked by the binding of HMGB1; subsequently, the degradation of Aβ40 may be inhibited in the microglial cytoplasm. In case of Aβ42, Aβ42 itself forms high-molecular-weight fibrils during incubation [33]. Therefore, the binding of HMGB1 may stabilize Aβ42 fibril formation, and high-molecular-weight complex of HMGB1 and Aβ42 fibril may interrupt the uptake of Aβ42 by microglia. Thus, extracellular HMGB1 may serve as a chaperone protein for Aβ and inhibit microglial Aβ clearance by interrupting Aβ40 degradation and Aβ42 internalization by microglia. On the other hand, RAGE, TLR2, and TLR4 are receptors for HMGB1 [30, 31]; they are also involved in microglial Aβ phagocytosis [49, 50]. Therefore, there is a possibility that the interactions of HMGB1 with these receptors on microglia may be related to the inhibitory events on Aβ.

Consistent with a previous study [13], plaques containing Aβ42 predominantly existed in AD brains, and Aβ40 accumulated on parts of Aβ42 plaques. Despite the restricted distribution of Aβ40, almost all plaques containing Aβ40 were markedly surrounded by activated microglia. We previously reported that small oligomers formed by Aβ40 strongly induce rat microglial reactions such as cytokine production [51]. Thus, Aβ40 may play an important role in microglial activation and/or recruitment on Aβ plaques. However, we have found that the level of HMGB1 was significantly increased in AD brains [33], and extracellular HMGB1 accumulated on Aβ plaques. Therefore, in AD brains, microglial degradation of Aβ40 and uptake of Aβ42 may be inhibited by extracellular HMGB1 despite the marked accumulation of reactive microglia on Aβ plaques. Moreover, in the present study, we demonstrated that Aβ40 is more readily degraded by the microglial cytosolic fraction than Aβ42. However, in the presence of exogenous HMGB1, the degradation of Aβ40 by microglia is inhibited, and a lot of Aβ40 granules are existed in the cytoplasm of rat microglia as shown in Figure 2(f). Interestingly, numerous microglia containing Aβ40 granules, but not Aβ42, have also been detected in AD brains [52]. Thus, this event in AD brain is well replicated by the treatment with Aβ40 in the presence of extracellular HMGB1 in primary-cultured rat microglia. Results suggest that our findings in the effect of HMGB1 on rat microglia may reflect on the pathological event induced in AD brain and are expected the critical implication of extracellular HMGB1 in the progression of AD pathologies. In addition, we have postulated that the origin of extracellular HMGB1 is leakage from dead neurons during the progression of AD [32], like ischemic neurodegeneration [53]. Extracellular HMGB1 leaked from dead neurons may then accumulate on Aβ plaques through its binding affinity for Aβ in AD brains.

It has been reported that the released HMGB1 is involved in the pathologies of various inflammatory-related disease [54]. In ischemic stroke [55] and intracerebral hemorrhage especially [56], extracellular HMGB1 is suggested to exacerbate brain insult through the disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), overfacilitation of microglia, and intense production of proinflammatory molecules. These studies also demonstrated that a neutralizing anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody and glycyrrhizin which bind to and inhibit cytokine-like activity of HMGB1 attenuate the brain insult induced by transient ischemia and intracerebral hemorrhage in rat, respectively. Therefore, there is a possibility that the neutralizing anti-HMGB1 monoclonal antibody and glycyrrhizin may bind to the extracellular HMGB1 accumulated on the Aβ plaques in the AD brain, cancel the inhibitory effects of HMGB1 on microglial Aβ phagocytosis, and then may provide novel therapeutic options for the AD treatment.

In conclusion, in the present study, we found that HMGB1 extracellularly accumulates on Aβ plaques containing Aβ40 in AD brains. We further demonstrated that HMGB1 has a binding affinity for Aβ40, and exogenous HMGB1 is internalized into rat microglial cytoplasm with Aβ40 and inhibits Aβ40 degradation. Subsequently, exogenous HMGB1 delays Aβ40 clearance in the culture medium. Thus, these results suggest that extracellular HMGB1 attenuates microglial Aβ clearance and is possibly involved in the progression of AD pathology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Toshiyuki Kawasaki for his technical assistance. This study was supported by the Frontier Research Programs of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; Grants-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; and Kyoto Pharmaceutical University Fund for the Promotion of Scientific Research.

References

- 1.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298(5594):789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Götz J, Chen F, Van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301L tau transgenic mice induced by Aβ42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293(5534):1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin WL, et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293(5534):1487–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Nakata Y, et al. Involvement of WAVE accumulation in Aβ/APP pathology-dependent tangle modification in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Pathology. 2009;175(1):17–24. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid β-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nature Medicine. 2000;6(8):916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodart JC, Bales KR, Gannon KS, et al. Immunization reverses memory deficits without reducing brain Aβ burden in Alzheimer’s disease model. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5(5):452–457. doi: 10.1038/nn842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janus C, Pearson J, McLaurin J, et al. Aβ peptide immunization reduces behavioural impairment and plaques in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):979–982. doi: 10.1038/35050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan D, Diamond DM, Gottschall PE, et al. A β peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408(6815):982–985. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, et al. Immunization with amyloid-β attenuates Alzheimer disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400(6740):173–177. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hock C, Konietzko U, Streffer JR, et al. Antibodies against β-amyloid slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2003;38(4):547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, Bibl M, et al. Highly conserved and disease-specific patterns of carboxyterminally truncated Aβ peptides 1-37/38/39 in addition to 1-40/42 in Alzheimer’s disease and in patients with chronic neuroinflammation. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;81(3):481–496. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwatsubo T, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Mizusawa H, Nukina N, Ihara Y. Visualization of Aβ42(43) and Aβ40 in senile plaques with end-specific Aβ monoclonals: evidence that an initially deposited species is Aβ42(43) Neuron. 1994;13(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT., Jr. The carboxy terminus of the β amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32(18):4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlgren KN, Manelli AM, Blaine Stine W, Baker LK, Krafft GA, Ladu MJ. Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(35):32046–32053. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, et al. Soluble amyloid β peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Pathology. 1999;155(3):853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perlmutter LS, Barron E, Chui HC. Morphologic association between microGlia and senile plaque amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience Letters. 1990;119(1):32–36. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90748-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paresce DM, Ghosh RN, Maxfield FR. MicroGlial cells internalize aggregates of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid β-protein via a scavenger receptor. Neuron. 1996;17(3):553–565. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paresce DM, Chung H, Maxfield FR. Slow degradation of aggregates of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid β- protein by microGlial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(46):29390–29397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Saeki M, et al. Galantamine-induced amyloid-β clearance mediated via stimulation of microGlial nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(51):40180–40191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takata K, Hirata-Fukae C, Becker AG, et al. Deglycosylated anti-amyloid beta antibodies reduce microGlial phagocytosis and cytokine production while retaining the capacity to induce amyloid beta sequestration. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;26(9):2458–2468. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Yanagisawa D, et al. MicroGlial transplantation increases amyloid-β clearance in Alzheimer model rats. FEBS Letters. 2007;581(3):475–478. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitamura Y, Shibagaki K, Takata K, et al. Involvement of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein family verprolin-homologous protein (WAVE) and Rac1 in the phagocytosis of amyloid-β(1-42) in rat microGlia. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2003;92(2):115–123. doi: 10.1254/jphs.92.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Tsuchiya D, Kawasaki T, Taniguchi T, Shimohama S. Heat shock protein-90-induced microGlial clearance of exogenous amyloid-β1-42 in rat hippocampus in vivo. Neuroscience Letters. 2003;344(2):87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00447-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kakimura JI, Kitamura Y, Takata K, et al. MicroGlial activation and amyloid-β clearance induced by exogenous heat-shock proteins. FASEB Journal. 2002;16(6):601–603. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0530fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streit WJ, Sammons NW, Kuhns AJ, Sparks DL. Dystrophic MicroGlia in the Aging Human Brain. Glia. 2004;45(2):208–212. doi: 10.1002/glia.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. MicroGlial dysfunction and defective β-amyloid clearance pathways in aging alzheimer’s disease mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(33):8354–8360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller S, Scaffidi P, Degryse B, et al. The double life of HMGB1 chromatin protein: architectural factor and extracellular signal. EMBO Journal. 2001;20(16):4337–4340. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418(6894):191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JS, Svetkauskaite D, He Q, et al. Involvement of toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(9):7370–7377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kokkola R, Andersson A, Mullins G, et al. RAGE is the major receptor for the proinflammatory activity of HMGB1 in rodent macrophages. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2005;61(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2005.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Tsuchiya D, Kawasaki T, Taniguchi T, Shimohama S. High mobility group box protein-1 inhibits microGlial Aβ clearance and enhances Aβ neurotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2004;78(6):880–891. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Kakimura JI, et al. Role of high mobility group protein-1 (HMG1) in amyloid-β homeostasis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;301(3):699–703. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura Y, Shimohama S, Kamoshima W, et al. Alteration of proteins regulating apoptosis, Bcl-2, Bcl-x, Bax, Bak, Bad, ICH-1 and CPP32, in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Research. 1998;780(2):260–269. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Games D, Adams D, Alessandrini R, et al. Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. Nature. 1995;373(6514):523–527. doi: 10.1038/373523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274(5284):99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holcomb L, Gordon MN, Mcgowan E, et al. Accelerated Alzheimer-type phenotype in transgenic mice carrying both mutant amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 transgenes. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(1):97–100. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campion D, Dumanchin C, Hannequin D, et al. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1999;65(3):664–670. doi: 10.1086/302553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, et al. Decreased clearance of CNS β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2010;330(6012):p. 1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simard AR, Soulet D, Gowing G, Julien JP, Rivest S. Bone marrow-derived microGlia play a critical role in restricting senile plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2006;49(4):489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El Khoury J, Toft M, Hickman SE, et al. Ccr2 deficiency impairs microGlial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(4):432–438. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boche D, Denham N, Holmes C, Nicoll JAR. Neuropathology after active Aβ42 immunotherapy: implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;120(3):369–384. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicolll JAR, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, Weller RO. Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-β peptide: a case report. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(4):448–452. doi: 10.1038/nm840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tjernberg LO, Callaway DJE, Tjernberg A, et al. A molecular model of Alzheimer amyloid β-peptide fibril formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(18):12619–12625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kallijärvi J, Haltia M, Baumann MH. Amphoterin includes a sequence motif which is homologous to the Alzheimer’s β-amyloid peptide (Aβ), forms amyloid fibrils in vitro, and binds avidly to Aβ . Biochemistry. 2001;40(34):10032–10037. doi: 10.1021/bi002095n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iwata N, Higuchi M, Saido TC. Metabolism of amyloid-β peptide and Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2005;108(2):129–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiu WQ, Walsh DM, Ye Z, et al. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates extracellular levels of amyloid β- protein by degradation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(49):32730–32738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimizu E, Kawahara K, Kajizono M, Sawada M, Nakayama H. IL-4-induced selective clearance of oligomeric β-amyloid peptide 1-42 by rat primary type 2 microGlia. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(9):6503–6513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lue LF, Walker DG, Brachova L, et al. Involvement of microGlial receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE)in Alzheimer’s disease: identification of a cellular activation mechanism. Experimental Neurology. 2001;171(1):29–45. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tahara K, Kim HD, Jin JJ, Maxwell JA, Li L, Fukuchi KI. Role of toll-like receptor signalling in Aβ uptake and clearance. Brain. 2006;129(11):3006–3019. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takata K, Kitamura Y, Umeki M, et al. Possible involvement of small oligomers of amyloid-β peptides in 15-deoxy-Δ12,14 prostaglandin J2-sensitive microGlial activation. Journal Pharmacological Sciences. 2003;91(4):330–333. doi: 10.1254/jphs.91.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Akiyama H, Mori H, Saido T, Kondo H, Ikeda K, McGeer PL. Occurrence of the diffuse amyloid β-protein (Aβ) deposits with numerous Aβ-containing Glial cells in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Glia. 1999;25(4):324–331. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(19990215)25:4<324::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faraco G, Fossati S, Bianchi ME, et al. High mobility group box 1 protein is released by neural cells upon different stresses and worsens ischemic neurodegeneration in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;103(2):590–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2005;5(4):331–342. doi: 10.1038/nri1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu K, Mori S, Takahashi HK, et al. Anti-high mobility group box 1 monoclonal antibody ameliorates brain infarction induced by transient ischemia in rats. FASEB Journal. 2007;21(14):3904–3916. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8770com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohnishi M, Katsuki H, Fukutomi C, et al. HMGB1 inhibitor glycyrrhizin attenuates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced injury in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(5-6):975–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]