Abstract

Background:

There is abundant literature delving into whether periodontal infection contributes to atherosclerosis. However, whether periodontitis is a definite risk factor for atherosclerosis still remains empirical, with no systematic reviews or longitudinal studies to confirm this hypothesis. The prevalence of periodontitis and coronary artery disease also varies among racial and ethnic groups based on various factors such as diet, lifestyle, and genetic predisposition. This study was designed in a south Indian population with the aim of assessing and correlating the lipid levels (a surrogate biomarker for coronary heart disease) in patients with periodontitis and health.

Aims:

(1) To assess the levels of total cholesterol, low density lipoproteins (LDL), high density lipoproteins (HDL), and triglycerides in periodontal disease, and health in a south Indian population. (2) To assess associations between elevated lipid profiles and periodontal disease.

Materials and Methods:

This case control study included 60 individuals. Blood sampling for lipid levels and periodontal examination were performed for each study group.

Statistical Analysis:

Appropriate statistical tools like Chi-square (P<0.05) and student's “t” test were used. The lipid levels were separately regressed using logistic regression to determine any association with periodontitis cases.

Results:

The differences between the mean lipid levels of cases and controls were not statistically significant (P>0.05) after eliminating confounding factors. Odds Ratio=(Total cholesterol (1.005), HDL (0.971), LDL (1.006), VLDL (0.997), CHO-HDL (1.358), TGL (1.007), LDL-HDL (1.180)). The odds ratio stated that there is no significant relation between the lipid levels and periodontal condition. The above findings confirm that there is still no concrete evidence which determines if periodontitis is an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Future periodontal interventional studies and assessment of genetic markers can ascertain the validity of this hypothesis.

Conclusion:

There is no association among periodontal disease and the levels of total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides.

Keywords: Coronary heart disease, periodontal disease, periomedicine, serum lipid levels, surrogate biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

It is more than a century since a connection between the mouth and the rest of the body first appeared in the medical literature. The notion of oral sepsis then termed as the “Focus of infection” was extensively debated among the dentist and the physician.[1] Numerous diseases of unknown etiology were thought to be causally linked to the common oral infection such as dental caries and the pyorrhea.[2] The focal infection theory fell into disrepute when it was found that extraction failed to eliminate or reduce the systemic disease to which the infected teeth were linked.[3] However, recent evidence-based literature again strongly suggests that oral health is indicative of systemic health supporting the association between periodontal disease and systemic conditions.[4] This has led to the evolution of a new branch in periodontology, namely Periomedicine. Significant associations between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, preterm low birth weight, and osteoporosis have been discovered, bridging the once wide gap between medicine and dentistry.[5]

Cardiovascular diseases, which globally still rank first in the list of morbidity and mortality, are common in many adult populations,[6] as is chronic periodontitis. Elevated levels of blood cholesterol leading to obesity, hypertension and diabetes mellitus are well-recognized risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. These surrogate measures, however, can only partly account for the occurrence of future cardiovascular diseases.[7] Chronic bacterial infections, including periodontitis have been associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease.[8] Systemic exposure to infectious challenges such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide, as in periodontitis, can result in the release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF -α) that alter fat metabolism and promote hyperlipidemia[9] and atherosclerosis. Bacterial translocation from periodontal pockets causes release of inflammatory mediators systemically, leading to monocyte activation and alteration in the lipoproteins towards a more atherogenic profile.

Obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI)≥30.0 kg/m2, (National Institute of Health), is a risk factor for several chronic diseases, most notably hypertension, type II diabetes, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease.[10] Recent studies have suggested that obesity is also related to oral diseases, particularly periodontitis.[11–13] Cutler et al.,[14] in their article, stated that there existed a close relationship between damage to the periodontium, increased concentration of lipids in blood, and the presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis antibodies. Hyperlipidemia causes hyperactivity of white blood corpuscles (increased production of oxygen radicals) which may be associated with the development of periodontitis in adults.[15] Obesity is second to smoking as a strong risk factor for inflammatory periodontal tissue destruction.[16]

The chances of periodontal disease increasing the risk of coronary heart disease, however, have to be explored further. Also, there is still uncertainty regarding ethnic differences in the prevalence, progression, and risk of coronary artery disease.[17] The present study was done to assess the levels of total cholesterol, low density lipoproteins (LDL), high density lipoproteins (HDL), and triglycerides in periodontally diseased and healthy individuals of South Indian population. Further, associations between elevated lipid profiles and periodontal disease were also assessed to enable preventive measures to be taken against cardiovascular disease (CVD) by periodontal management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty six male and twenty four female, in the age group of 30-50 years, attending the out-patient Department of Periodontology between June 2009 and June 2010, constituted the study population. They were divided into case and control groups, comprising 30 patients each, based on a convenience sample. The case group comprised of generalized chronic periodontitis patients. The patients were included under the case group if they had probing depths ≥5 mm. The controls were periodontally healthy individuals. The periodontal examination was done by a single examiner. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the relevant regional committee. The participants in the study were selected based on a questionnaire and their socio-demographic details were extracted before conducting the physical and periodontal examination. All the participants were informed in detail of the procedure and signed a consent form in advance of their participation in this study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with >20 teeth

Age: 30-50 years old

BMI: In the range of 18.50-24.99 (World Health Organization 2004)

Fasting blood sugar: <100 mg/dl

Non-smokers

Patients who are willing to give an informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Previous periodontal treatment over the past six months

Known history of hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension or any previous medications for the same

Antibiotics taken for the past three months.

Sample size

Using the sample size determination formula for single proportion, [ ] assuming proportion of elevated totalcholesterol in periodontitis case is 20% (i.e., P=20%) and allowing for the absolute difference of 15% (i.e., P ranges from 5% to 35%, L=15%) with the level of significance being 5% (α=0.05), Zα=1.96, the estimated sample size was 28. Thus, a sample of 30 cases and controls were taken.

] assuming proportion of elevated totalcholesterol in periodontitis case is 20% (i.e., P=20%) and allowing for the absolute difference of 15% (i.e., P ranges from 5% to 35%, L=15%) with the level of significance being 5% (α=0.05), Zα=1.96, the estimated sample size was 28. Thus, a sample of 30 cases and controls were taken.

For statistical analysis*, appropriate estimates like mean and standard deviation (SD), proportions, percentages, and correlation co-efficient along with 95% confidence interval were calculated. Appropriate statistical tools like, Chi-square (χ2) test were used for testing equality of proportion, discordant proportion in matched pairs, trends and association between categorical variables. Student's ‘t’ test was used to compare difference between the means.

Study protocol

This study included

Blood sampling

Periodontal examination

Radiographic evaluation.

Blood sampling

The individuals had their blood samples collected at the clinical laboratory, after minimum of 12 hrs fasting for the biochemistry analysis of lipid levels. Collection of 5 ml of blood was done in a red top vacutainer or a dry plain test tube, and centrifuged after 45 min. The separated serum was collected in a clean storage vial. The levels of lipids were analyzed by homogenous enzymatic calorimetry using COBAS6000 instrument test codes.

Clinical periodontal examination

This was performed with a plane mouth mirror, explorer, Naber's and William's periodontal probes.

The clinical parameters evaluated were

Oral hygiene index simplified (Greene and Vermillion 1964)

Probing pocket depth

Clinical attachment level

Tooth mobility based on Miller's mobility index [Table 2, Figure 2].

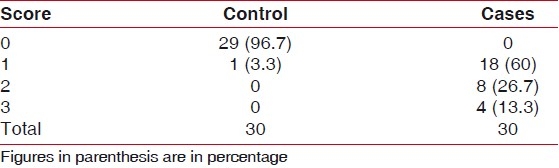

Table 1.

Distribution of furcation score by groups

Figure 1.

Furcation grade by group

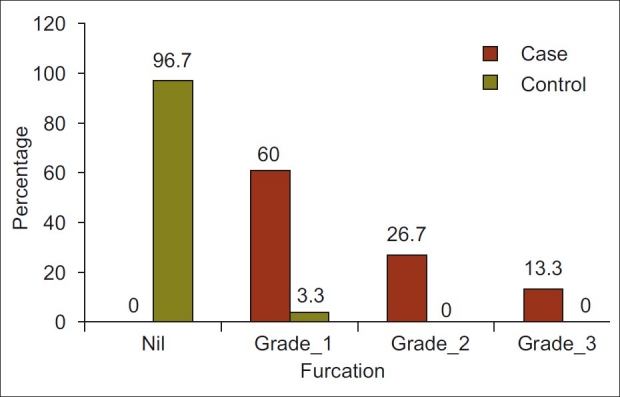

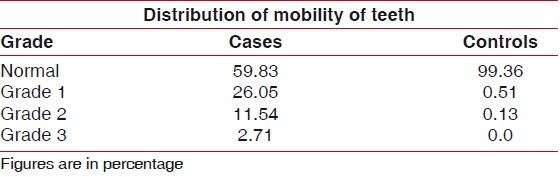

Table 2.

Mobility of teeth

Figure 2.

Distribution of mobility of teeth

Radiographic evaluation

An Orthopantomograph was done for radiographic interpretation of bone levels.

*The EPI INFO software (Centre for disease control and prevention, Atlanta, USA) was used to analyze the data).

RESULTS

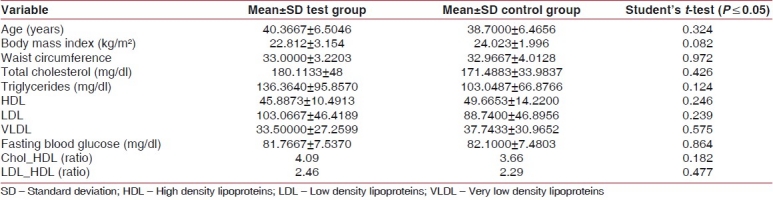

Sixty individuals of both genders, aged 30-50 years, attending the out-patient department constituted the study group, the mean age for controls and cases being 38.7000±6.4656 and 40.3667±6.5046, respectively. Mean values, SD, and respective P values of the variables according to the groups, namely test and control groups are shown in Table 3. The P values did not show any statistical significance. The P values of total cholesterol, high and low density lipoproteins, and triglycerides did not show any statistical significance. The HDL-LDL ratio was also not statistically significant as seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variables considered with P values

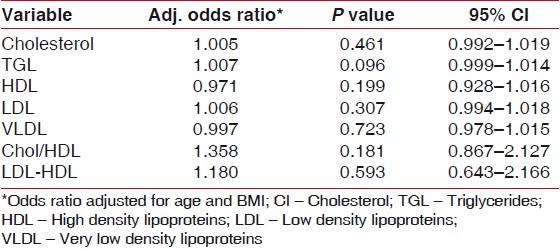

Logistic regression

To determine whether lipids are actually associated with the periodontitis, each one of the lipid levels were separately regressed using logistic regression. We controlled the influences of the age and the BMI. The results [Table 4] of the regression analysis indicate that the lipid levels are not associated with diseased periodontal conditions. Based on the logistic regression analysis in this study, the lipid profile values were not significantly higher both in cases and controls in spite of eliminating confounding factors. When compared, the periodontal parameters were also not associated with the lipid values. The lipid-level values were total cholesterol (1.005), HDL (0.971), LDL (1.006), VLDL (0.997), CHO-HDL (1.358), TGL (1.007), and LDL-HDL (1.180) [Table 4]. The odds ratio stated that there is no significant relation between the lipid levels and periodontal condition.

Table 4.

Results of Logistic regression analysis

DISCUSSION

This case-control study, which was conducted with 60 individuals, was aimed at assessing the lipid levels of patients in periodontal disease and health. The serum lipid levels were within limits for both case and control groups with statistically insignificant P values [Table 3]. There was also no statistical evidence to prove that patients with periodontitis have higher lipid levels compared to healthy patients [Table 3]. Literature contains contradictory results about the relationship between serum lipid levels and periodontal status. This study, done in south Indian population, adds a racial perspective to the results obtained [Table 3]. Sridhar et al.[18] have also conducted a study measuring serum lipid levels in four groups of patients, namely, healthy, chronic periodontitis, coronary heart disease with and without periodontitis, and concluded that periodontitis did not cause an increase in lipid levels in patients with or without coronary heart disease (CHD). The results of this study are also in concordance with that of Katz et al.[19] Hujoel et al.[20] assessed the impact of periodontitis on patients with pre-existing/self-reported cardiovascular disease, and concluded that periodontitis/gingivitis did not elevate CHD risk among them. Loesche, et al.,[21] however, determined a significant association between periodontal conditions and the concentration of triglycerides in the blood. Morrison, et al.,[22] in their cohort study, found a statistically significant association between periodontitis and fatal CVD. Katz et al.[19] indicate that total blood cholesterol and LDL levels were significantly higher in male patients with periodontitis, compared to patients with healthy periodontium and gingivitis. However, we did not find any gender predilection in this study.

The disagreement observed in the various studies that relate periodontal disease with hyperlipidemia maybe in part due to

the great number of confounding variables involved such as diet and physical activity habits, socio-economical conditions, obesity, age, stress, and geographical location, which are factors subjected to the environment in which the individual lives, interfering with the study results

-

the methods of assessing periodontitis, namely, based only on

Another question which needs to be addressed is whether periodontitis should be aggressively treated as a preventive measure for CVD. Beck et al., in 2008,[25] however, demonstrated that non-surgical routine periodontal therapy did not reduce the risk of serious cardiovascular events. Shruthi et al.[26] when comparing the impact of periodontal therapy on lipid levels, found all lipid levels except HDL to be improved after phase I therapy. The proposed randomized control trial by Ramirez et al.,[27] is expected to provide more evidence on the effects of different treatment modalities on levels of surrogate biomarkers for CVD. Even though so many studies with conflicting results are presented in the literature, there is still no concrete evidence which determines if periodontitis is an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic CVD.

However, there are certain clinical recommendations to keep in mind.

Patient education

A close collaboration between the cardiologist and periodontist to optimize risk reduction

Periodic evaluation of periodontal and cardiac status.

Periodontal intervention therapy to reduce possible risk of coronary heart disease.

CONCLUSION

The above findings demonstrated that there is no association among periodontal disease and the levels of total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides.

Future directions

Newer diagnostic and monitoring methods using valid surrogate markers such as lipid profile levels after periodontal treatment[27] and genetic markers to assess the relationship between cardiovascular diseases and periodontal health[28] promise a better understanding on the bidirectional effects of this relationship.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunter W. Oral sepsis as a cause of disease. Br Med J. 1900;1:215–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.2065.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller WD. The human mouth as a focus of infection. Dent Cosmos. 1981;33:689–789. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Focal infection. J Am Med Assoc. 1952;150:490–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.1952.03680050056016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck JD, Garcia RG, Heiss G, Volconos P, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67(suppl):1123–37. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scannapieco FA. Position paper. Periodontal disease as a potential risk factor for systemic diseases. J Periodontol. 1998;69:841–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics -2007 update. A report from the. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EUROASPIRE study group (anonymous) A European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: Principal results. European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1569–82. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meurman JH, Sanz M, Janket SJ. Oral health, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2004;15:403–13. doi: 10.1177/154411130401500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacopino AM, Cutler CW. Patho-physiological relationship between Periodontitis and systemic disease: Recent concepts involving serum lipids. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1375–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.8.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, et al. Prevalence of Obesity, Diabetes and Obesity-Related Risk Factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Kubo M, Lida M, et al. Relationship between obesity, glucose tolerance, and periodontal disease in Japanese women: The Hiasyama Study. J Periodontol Res. 2005;40:346–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Zahrani MS, Bissada NF, Borawskit EA. Obesity and periodontal disease in young, middle aged and older adults. J Periodontol. 2003;74:610–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Ho A, Nishimura F, Murayama Y. A proposed model linking inflammation to obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections. J Periodontol. 2005;76(11 suppl):2075–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cutler CW, Shinedling EA, Nunn M, Jotwani R, Kim BO, Nares S, et al. Association between periodontitis and hyperlipidemia: Cause or Effect. J Periodontol. 1999;12:1429–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.12.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause S, Pohl A, Pohl C, Liebrenz A, Ruhling K, Loesche W. Increased generation of reactive oxygen species in mononuclear blood cells from hypercholesterolemia patients. Thromb Res. 1993;71:237–40. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishida N, Tanaka M, Hayashi N, Nagata H, Takeshita T, Nakayama K, et al. Determination of smoking and obesity as periodontitis risks using the classification and regression tree method. J Periodontol. 2005;76:923–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orakzai SH, Orakzai RH, Nasir K, Santos RD, Edmundowicz D, Budoff MJ, et al. Subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: Racial profiling is necessary! Am Heart J. 2006;152:819–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sridhar R, Byakod G, Pudakalkatti P, Patil R. A study to evaluate the relationship between periodontitis, cardiovascular disease and serum lipid levels. Int J Dent Hygiene. 2009;7:114–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz J, Flugelman MY, Goldberg A, Heft M. Association between periodontal pocket and elevated cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. J Periodontol. 2002;73:494–500. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hujoel PP, Drangsholt M, Spiekerman C, DeRouen TA. Pre-exisiting cardiovascular disease and periodontitis: A Follow up study. J Dent Res. 2002;81:186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loesche W, Karapetow F, Pohl A, Pohl C, Kocher T. Plasma lipid and blood glucose levels in patients with destructive periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:537–41. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027008537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison HJ, Ellison LF, Taylor GW. Periodontal disease and risk of fatal coronary heart and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovascular Risk. 1999;6:7–11. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck JD, Eke P, Heiss G, Madianos P, Couper D, Lin D, et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease: A reappraisal of the exposure. Circulation. 2005;112:19–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.511998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell TH, Ridker PM, Ajani UA, Hennekens CH, Christen WG. Periodontal disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease in US male physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:445–50. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck JD, Couper DJ, Falkner KL, Graham SP, Grossi SG, Gunsolley JC, et al. The periodontitis and vascular events (PAVE) pilot study: Adverse events. Journal of Periodontology. 2008;79:90–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tandon S, Dhingra MS, Lamba AK, Verma M, Munjal A, Faraz F. Effect of periodontal therapy on serum lipid levels. Indian J Med Spec. 2010;1:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramirez JH, Arce RM, Contreras A. Periodontal treatment effects on endothelial function and cardiovascular disease biomarkers in subjects with chronic periodontitis: protocol for a randomized control trial. Trials. 2001;12:46. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornman KS, Duff GW. Candidate genes as potential links between periodontal and cardiovascular diseases. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:48–57. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]