Abstract

Background:

Chronic periodontitis is the inflammation within the supporting tissues of the teeth resulting in attachment loss and bone loss. There are certain environmental factors such as smoking that can modify the host response to plaque organisms; hence can account for the aggressive progression of the disease. Smokers show a decreased expression of clinical inflammation even in the presence of abundant plaque accumulation. Neutrophils are the predominant host defense cells which protect the periodontal tissues from plaque organisms, deficiencies of neutrophil function, such as chemotaxis and phagocytosis, often result in increased susceptibility to periodontitis. Smoking can induce alteration in the neutrophil function; therefore, it is of importance to know the changes caused by smoking on neutrophil chemotaxis. This study will provide an essential basis for evaluating the role of nicotine in pathogenesis of periodontal disease by assessing the neutrophil activity.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 60 smokers and 60 non smokers were examined for this study. Both the groups included 20 subjects with gingivitis, periodontitis, and healthy periodontium. The periodontal status of the study subjects were assessed by gingival index, Russels periodontal index, sulcus bleeding index, and clinical attachment level. The blood sample was taken from each individual for the chemotactic analysis using agarose method.

Results:

In this study, there was a significant decrease in the neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers with gingivitis, periodontitis, and healthy periodontium, compared to non smokers with similar findings.

Conclusion:

Delayed neutrophil chemotaxis was found in smokers compared to non smokers with same periodontal status.

Keywords: Chemotaxis, nicotine, polymorphonuclear cells, smoking

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is the most common cause of tooth mortality. The disease is caused by bacterial colonization of the surfaces of the teeth in the region of the gingival sulcus and extension of microbial plaque apically. Bacteria insinuate themselves between the gingival tissues and the root surface to cause the extensive inflammation, pocket formation, and destruction of the soft tissue and bone housing the root surfaces of the teeth.[1] Chronic periodontitis results from a complex interplay of bacterial infection and host response often modified by behavioral factors.[2] Smoking has been found to be a major environmental risk factor associated with generalized forms of severe periodontitis. It causes reduction in clinical signs of gingivitis suggesting that nicotine mediates local vasoactive effects and delays inflammatory response against the plaque organisms.[3] Even though the primary etiology of periodontal disease is bacteria, the host response determines susceptibility to disease.[4] Nicotine metabolites concentrate in the periodontium and causes promotion of vasoconstriction and impairment in functional activity of polymorphs and macrophages. Accumulation of neutrophils in gingival connective tissue, junctional epithelium and their migration into the gingival crevice through gingival crevicular fluid is an important feature of periodontal disease.[3] The presence of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) in the crevicular fluid serves to protect the periodontal ligament tissues against microbial attack and counteract the effects of microbes by phagocytosis and ultimately killing them.

The role of PMN in innate immunity is underscored by congenital defects such as chronic granulomatous disease, Chediak-Higashi syndrome, and leukocyte adhesion deficiency syndrome. These illnesses are characterized by genetic abnormalities that alter PMN functional responses, leading to recurrent bacterial infection and severe periodontal disease.[2] PMN cells accumulate at the site of inflammed periodontal tissues. In subjects with suppressed immunity, they fail to migrate through the gingival crevice, they release enzymes such as elastase into the surrounding connective tissue; hence contributing directly to more aggressive form of tissue destruction.[3] In the light of above facts, this study is designed to investigate neutrophil chemotaxis in peripheral blood of smoking and non smoking patients with gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, healthy periodontium, and to compare it between each other.

Aim of this study was to compare the peripheral blood neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers and non smokers with healthy periodontium, gingivitis, and chronic periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

This randomized control study was carried out on peripheral blood samples, collected from 120 patients, 68 male and 52 female in the age group range of 35-55 years with a mean age of 40 years reporting to Department of Periodontics, Coorg institute of dental sciences. Ethical committee approval from the college ethical committee was taken, and written consent was obtained from all the patients.

The patients were grouped as follows: 1) group I - non smokers: - group I was sub grouped into three sub groups: Group Ia - Healthy periodontium subjects, group Ib - gingivitis subjects, and group Ic - chronic periodontitis subjects with pocket depth of more than 5 mm; and 2) group II - current smokers: - group II was sub grouped into three sub groups: Group IIa - healthy periodontium subjects, group IIb - gingivitis subjects, and group II c - chronic periodontitis subjects with pocket depth of more than 5 mm.

Following criteria were used to exclude subjects from entering the study 1) patients with systemic diseases, which affects the neutrophil functions, such as leukocyte disorders, neutropenia, stress, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, Struge – Weber syndrome, Wegener's granulomatosis, cyclic neutropenia, Chediak Higashi syndrome, and Lazy leukocyte syndrome; 2) patients on medication, which affects the neutrophil functions, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, amphotericin-B, anticancer drugs, and patients undergoing radiation therapy; and 3) Aggressive periodontitis patients. Inclusion criteria for the study were 1) patients with age group; 35 to 55 years, 2) smokers and non smokers with healthy periodontium, gingivitis, and chronic periodontitis.

All the patients received a full mouth periodontal examination consisting of the following indices, gingival index, sulcus bleeding index, clinical attachment level, periodontal index (Rusell AL, 1956). All teeth present were probed using a William's Graduated Periodontal probe. Each tooth was probed at six sites from gingival margin to base of the pocket (buccal, mesiobuccal, distobuccal, lingual, mesiolingual, and distolingual). Readings were taken from the nearest mm with 0.5 mm, being the nearest, was rounded off to the lower whole number. The CAL was recorded as the distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the base of the pocket. Total score of all teeth divided by the number of teeth examined gave the average clinical attachment loss for the patient per tooth.

Sample collection

Three milliliters of venous blood was collected by venipuncture and stored in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid until analyzed for neutrophil chemotaxis. The neutrophil chemotaxis assay was carried out using under agarose method and casein was used as chemoattractant.

Preparation of agarose gel

Reagents used are 0.024 g/ml agarose (high media) , supplemented minimum eagle media (MEM) , casein (Chemoattractant), and phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Staining reagents used were methanol, formalin, and Leishmans stain.

Two hundred and forty milligrams of agarose is dissolved in double distilled water by heating in boiling water for 10-15 minutes and then cooled to 40°C. A total of 1.2 g MEM in 10 ml of sterilized water is taken and heated to 500°C. One milliliter of MEM is mixed in 1 ml of heat inactivated pooled human serum, 0.1 ml of 7.5% sodium bicarbonate, and add 2.9 ml sterile distilled water to make the volume to 5 ml.

Five milliliters of pre-warmed supplemented with MEM mixture is added to 5 ml of 0.024 g/ml of agarose. Add 3 ml mixture to the slides and allow it to solidify. Cut series of three wells in 3 mm diameter. After preparation of agarose coated slides, blood samples taken from the patients were subjected to centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 15-20 min. Supernatant was discarded and buffy coat rich in neutrophils were carefully pipetted out and diluted with PBS which was charged into the four outer wells prepared on the agarose gel slides. Casein, a chemo attractant, is charged in the central well.

These slides were incubated at 37°C in incubator for 2 h, after incubation, the slides were fixed and stained [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Agarose coated slide kept for incubation

Staining procedure

Slides were flooded with 3-5 ml of methanol until all the wells were completely immersed in it for 30 min and removed, it was flooded again with 3-5 ml formalin for 30 min and then agarose was removed carefully.

These slides were then washed carefully in flowing water and stained with Leishmans stains for 10-15 min; after staining, these slides were observed under microscope for chemotaxis [Figure 2]. Ocular micrometer was used to measure the distance traveled by the neutrophils towards the chemoattractant. Ocular micrometer was placed in the focal plane of the microscope [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Interpretation of migrated neutrophil

Figure 3.

Measurement of neutrophil chemotaxis in microns

RESULTS

The results of our study indicated that neutrophil chemotaxis in blood was significantly decreased (P<0.05) in smokers when compared to non smokers. It was also found that peripheral blood neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers with gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, and healthy periodontium was decreased compared to non smokers with gingivitis, chronic periodontitis and healthy periodontium.

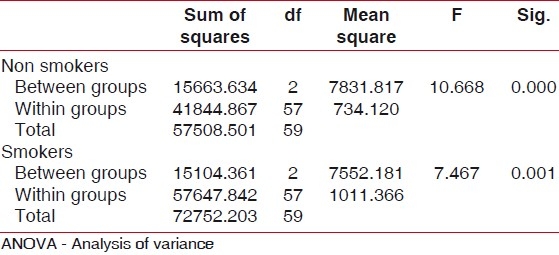

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for overall comparison of neutrophil chemotaxis among the two groups and six sub groups [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Mean pattern of neutrophil chemotaxis between two groups assessed by ANOVA, it was observed that neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers signifi cantly decreased compared to non smokers

Table 2.

Mean pattern of neutrophil chemotaxis between six sub groups assessed by ANOVA - it was observed that neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers with gingivitis, periodontitis, healthy periodontium significantly decreased compared to non smokers with gingivitis, periodontitis, and healthy periodontium

Neutrophil chemotaxis in blood has significantly decreased (P=0.000) in smokers (group I) compared to non smokers (group II) and the difference is statistically significant.

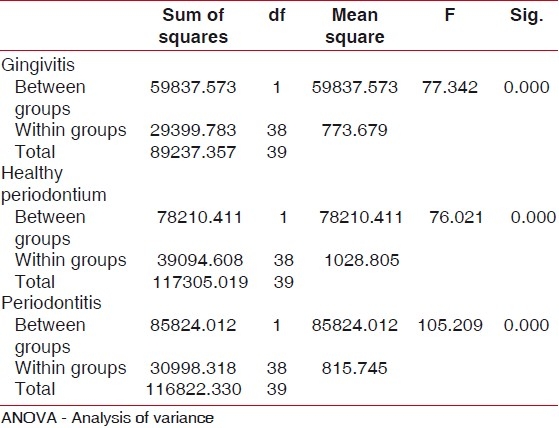

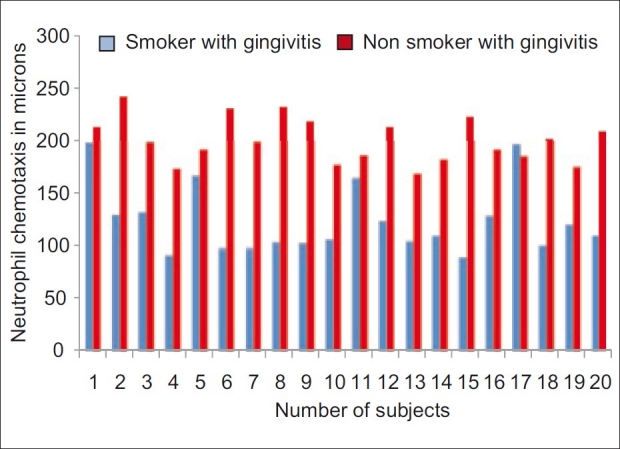

Difference in mean neutrophil chemotaxis between smokers and non smokers with gingivitis was analyzed by student's t test as shown in Table 3. Analysis showed there is significant difference between the neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers and non smokers in gingivitis group [Figure 4].

Table 3.

One-sample t-test analysis showing difference in neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers and non smokers compared with healthy gingival, gingivitis, and periodontitis group

Figure 4.

Comparison of neutrophil chemotaxis between smokers and non smokers with gingivitis

The above table shows the difference in neutrophil chemotaxis by one sample t test analysis in smokers and non smokers when compared in healthy gingival, gingivitis, and periodontitis group. The t value in healthy gingiva (smokers, it is 20.2500, and in non smokers, it is 33.2577). The t value in gingivitis patients (smokers=16.7934 and non smokers=42.1405). The t value in periodontitis patients (smokers, it is 16.2679, and in non smokers, it is 33.9929). In all the three groups, t values are highly significant suggesting considerable difference in neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers and non smokers.

DISCUSSION

Periodontitis is a multi-factorial disease affected by bacterial challenge, host systemic factor, genetic factor, and environmental risk factors. There exists a balance between the bacterial challenge and host immune response, alteration in this can lead to severe periodontal destruction.

The neutrophil is an important component of the host response to bacterial infection. Increased susceptibility to recurrent bacterial infections is observed in patients with defective formation and function of PMNs.[5] Among the leukocytes, PMNs are the most abundant phagocytes found at the site of acute inflammation and has an important role in the defense of the marginal periodontal tissues against bacterial invasion.[6]

Smoking exerts a major effect on the protective elements of the immune response, resulting in an increase in the extent and severity of periodontal destruction. It down regulates the immune response to bacterial challenge.[7] Smoking affects the subgingival ecology, gingival tissue vasculature, the host inflammatory response, immune response, inhibits respiratory burst of PMNs, and the healing potential of the periodontal connective tissues.[8] The negative effects of smoking on PMNs were first described by Eichel and Shahrik. It was reported that there is reduced function and mobility of PMNs even after smoking one cigarette, suggesting dose dependent effect.[9]

Casein was used as chemoattractant and chemotaxis was measured using ocular micrometer. The results of our study showed a statistically significant decrease in neutrophil chemotaxis in peripheral blood of gingivitis, chronic periodontitis patients, and patients with healthy periodontium in smokers group compared to neutrophil chemotaxis of the chronic periodontitis, gingivitis, and healthy periodontium subjects in the non smokers group.

Neutrophil chemotaxis in blood was significantly decreased in smokers when compared to non smokers. It was also found that peripheral blood neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers with gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, and healthy periodontium was decreased compared to non smokers with gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, and healthy periodontium. This was in accordance with a study by Sighush et al.[10]

Further it was seen that there is delayed neutrophil chemotactic activity manifested by smokers with gingivitis compared to non smokers with gingivitis, which is in correlation with the study conducted by Preber et al.[11] The results of which stated smoking alters peripheral vasoconstriction and decreases neutrophil migration.

The results of our study also showed decreased neutrophil chemotaxis in smokers with periodontitis compared to non smokers with periodontitis, which is in accordance with the study by Fredriksson M et al.[11] which stated that smoking brings about changes in acute phase proteins and haptoglobin affecting the neutrophil functional activity.

Smokers showed reduced neutrophil chemotaxis as compared to non smokers in subjects with healthy periodontium. This is in accordance with a study by Van Dyke et al.[9] which showed that smoking brings about changes in the morphology and adhesion property of neutrophils leading to reduced function ability.

Impaired PMN function seen in smokers contributes to an increased risk for periodontal diseases in later life. These data further support the importance of smoking as a risk factor for periodontitis. Future longitudinal studies are required to investigate PMN function in smokers and non-smokers with periodontal disease.

CONCLUSION

Based on the results of this study, a significantly reduced chemotaxis in peripheral blood neutrophils in smoker subjects was observed. Hence, we can conclude that smokers show a neutrophil chemotactic defect in all the three groups; gingivitis, periodontitis, and healthy periodontium.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Page RC, Sims TJ, Geissler F, Altman LC, Baab DA. Defective neutrophil and monocyte motility in patients with early onset periodontitis. Infect Immun. 1985;47:169–75. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.1.169-175.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergstrom J, Preber H. Tobacco use as a risk factor. J Periodontal. 1994;65:545–50. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.5s.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryder MI, Fujitaki R, Johnson G, Hyun W. Alterations of neutrophil oxidative burst by in vitro smoke exposure: Implication for oral and systemic diseases. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:76–87. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genco RJ. Host responses in periodontal diseases: Current concepts. J Periodontol. 1992;63:521–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.4s.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredriksson MI, Figueredo CM, Gustafsson A. Effect of periodontitis and smoking on blood leukocytes and acute-phase proteins. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1355–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.11.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews JB, Wright HJ, Roberts A. Hyperactivity and reactivity of peripheral blood neutrophils in chronic periodontitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:255–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genco RJ, Slots J. Host responses in periodontal diseases. J Dent Res. 1984;63:441–51. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630031601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genco RJ. Current view of risk factors for periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1041–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Dyke TE, Wilson-Burrows C, Offenbacher S, Henson P. Association of an abnormality of neutrophil chemotaxis in human periodontal disease with a cell surface protein: Infect Immun. 1987;55:2262–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2262-2267.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigusch B, Eick S. Altered chemotactic behavior of crevicular PMNs in different forms of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:162–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028002162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredriksson M, Carlos MS. Effect of periodontitis and smoking on blood leucocytes and accute phase proteins. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1355–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.11.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]