Abstract

Background:

The aim of the study was to clinically evaluate the effect of miswak as an adjunct to tooth brushing on plaque levels and gingival health in subjects diagnosed with mild to moderate chronic generalized marginal gingivitis in comparison with those of toothbrush users.

Materials and Methods:

The study comprised of 30 systemically healthy subjects, aged 18-35 years diagnosed with mild to moderate gingivitis. The study was designed as a randomized, single-blind, parallel-armed study. Subjects were randomly divided into three groups. Group A (toothbrush users), group B (toothbrush and miswak users), and group C (miswak users). Subjects were advised to use toothbrush, miswak, or both, three times daily depending on their respective allocations. Gingival index according to Loe and Silness, Plaque index, according to Turesky modified Quigley-Hein plaque index, and the digital photographs of the total labial surfaces of the teeth were taken for image analysis. Recording of data were done at baseline, 2nd, 4th, 6th, and 8th week time intervals. Obtained data were analyzed using repeated measure ANOVA and student t test (independent samples).

Results:

Group B showed statistically significant (P<0.0001) decrease in plaque score and gingival score compared to group A and group C, respectively, from 2nd to 8th week, whereas no statistical significant difference was found in plaque score, when group A was compared with group C (P>0.05) from 2nd to 4th week. Further at the 6th and 8th week, there was significant difference (P<0.05) in plaque score between group A and group C. The difference in gingival score was not significant (P<0.05), when group A was compared with group C on all the indicated time intervals.

Conclusion:

Results showed significant improvement in plaque score and gingival health when miswak was used as an adjunct to tooth brushing.

Keywords: Gingivitis, image analysis, miswak, plaque score, toothbrush

INTRODUCTION

Dental plaque is a well-known etiologic factor for gingival diseases. Dental plaque is solely responsible for the initiation and progression of gingival diseases.[1] The methods available for the maintenance of oral health are mainly mechanical and chemical. Tooth brushing is the most common mechanical method used to control plaque.[2,3] However, toothbrushes are rare in many third-world countries, where locally available chewing sticks are commonly used.[4]

The most common type of chewing stick, miswak, is derived from Salvadora persica, a small tree or shrub with a spongy stem and root, which is easy to crush between the teeth. Pieces of the root usually swell and become soft when soaked in water.[5] Miswak is a chewing stick used in many developing countries as a traditional toothbrush for oral hygiene.[4]

Reports on the oral health of miswak users are contradictory; several studies have claimed that chewing sticks are effective in reducing plaque and gingival inflammation.[5–8] When used properly, the miswak is reported to be as effective as a toothbrush.[5,6] It was found that the chewing stick removed plaque from interproximal sites to virtually the same extent as from other more accessible sites.[6] The conventional tooth brushing has been reported to be relatively ineffective for the removal of interproximal plaque.[6] The value of chewing sticks is believed to be in their mechanical cleansing action. The use of miswak has also been reported to inhibit the formation of dental plaque chemically and exert antimicrobial effect against many oral bacteria.[9]

However, some studies[10,11] have reported more plaque formation and gingival bleeding in individuals who used chewing sticks in comparison with toothbrush users. In few studies,[11] it has been found that the toothbrush was more efficient as an oral hygiene aid than the miswak.

Surprisingly, despite the widespread use of miswak since ancient times, relatively little scientific attention has been paid to its oral health beneficial effects. In 1987, World Health Organization encouraged the developing nations to use miswak for oral hygiene because of tradition, availability, and low cost.[12] Recently, various authors have concluded that chewing sticks or its extract has therapeutic effect on gingival diseases.[4,13]

Thus, a study was designed to clinically evaluate the effect of miswak stick as an adjunct to tooth brushing on plaque levels and gingival health in subjects diagnosed with mild to moderate chronic generalized marginal gingivitis in comparison with those of toothbrush users.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thirty subjects diagnosed with mild to moderate chronic generalized marginal gingivitis were selected randomly from the out patient department (OPD) presenting to JSS Dental College and Hospital, Mysore. A prior written informed consent was taken from all included subjects. The study was approved by ethical committee JSS University Mysore.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria included subjects to be within the age group of 18-35 years; subjects who were having full set of teeth; subjects who were diagnosed with mild to moderate chronic generalized marginal gingivitis; subject having a probing pocket depth less than or equal to 3 mm; and subjects showing gingival index[14] (Loe and Silness) more than 1, and plaque index[15,16] (Turesky modified Quigley-Hein plaque index) more than 1.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were the subjects who were systemically compromised; pregnant and lactating mothers; subjects having orthodontic appliance; subjects who have grossly decayed teeth, mal-positioned teeth or crowded teeth, overhanging restorations, crowns, and fixed partial dentures; patients who used antibiotics in the previous three months; and patients with xerostomia and on antihistamines were also excluded.

Design

The study was performed according to a randomized, single-blind (clinical investigator), parallel-armed design. Before the start of the study, during the first visit, intraoral examination was performed. Oral hygiene habits were recorded by a structured interview based on a prepared questionnaire. The questionnaire included education level, smoking habit, dental visit, usage of chewing stick and/or toothbrush and its frequency.

The subjects were randomly assigned to one of the three groups consisting of 10 subjects in each group.

Group A- Subjects were asked to brush with the provided toothbrush without toothpaste during morning, mid day, and evening.

Group B- Subjects were asked to brush with the provided toothbrush without toothpaste thrice daily, and in addition, miswak sticks were given to use during morning, mid day, and evening.

Group C- Subjects were asked to use miswak sticks during morning, mid day, and evening.

Subjects were trained and instructed on a model to use miswak or toothbrush (without toothpaste) or both, depending on the respective assigned group.

Sufficient numbers of commercially available standard sized (20 cm in length and 1 cm in diameter) miswak branch-lets/twigs (Miswak Haleemi®, Haleemi Natural Products, Karachi, Pakistan, 75700) [Figure 1] were purchased from local market of Mysore, India, and were stored in the refrigerator until implemented into the study.

Figure 1.

Demonstrating a miswak stick and a toothbrush used in the study

Subjects falling under group C were given fresh sticks of standard sized miswak sticks. Subjects falling under group A were given a new straight handled, medium soft toothbrush without toothpaste (Ajay Quest® Toothbrush, Raghav Lifestyle Products, New Delhi, India) [Figure 1]. Subjects falling under group B were given both miswak sticks and tooth brushes without toothpaste. Subjects using miswak (group B and C) were advised to use freshly prepared miswak stick at each indicated time interval and store in refrigerator packed in provided paper when not in use.

Clinical examination and image analysis

Recording of clinical indices and photographs were taken at baseline, 2nd 4th, 6th, and 8th week time intervals. The clinical parameters measured were: a) gingival index, according to Loe and Silness[14] and b) plaque index, according to Turesky modified Quigley-Hein plaque index.[15,16] Both gingival inflammation and plaque were registered at four sites per tooth (buccal, mesial, distal, and lingual) for all teeth, except the third molar, and were analyzed according to respective indexing system. Plaque was stained with erythrosine before scoring.

Photograph of stained plaque on anterior dentition was taken by using a digital camera (Kodak C713, Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY 14650), keeping the camera approximately perpendicular (90°) and at a distance of 25 cm from the labial surface of upper central incisor. Photographic images were analyzed by computer software (UTH SCSA Image Tool [IT version 2]) for the percentage of plaque coverage. The total labial teeth surfaces and the area covered by plaque were directly counted in pixels. The plaque area was then calculated in percentage of the total labial teeth surfaces. All images were coded and the analysis of the images was done in a blinded way. Ten images of each interval were analyzed and average was considered for each subject. The analysis of the images was done at baseline, 2nd 4th, 6th, and 8th week time intervals.

Statistical analysis

Recorded data were analyzed using software program (Statistical package version 17, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Chicago, IL). All parametric variables were analyzed using repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) for examining the mean differences from baseline to 8th week and Student's t test (independent samples) for comparison of mean differences between groups at specific time intervals. Differences were considered significant if P<0.05.

RESULTS

None of the participants complained of discomfort or showed any signs of adverse reactions with use of prescribed chewing sticks.

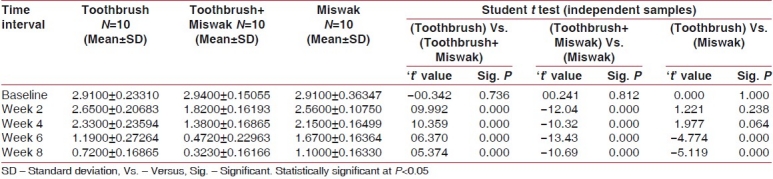

Comparison of plaque scores

Data analyzed by repeated measure of ANOVA for time and cleaning method interactions showed a significant reduction in plaque score (F=20.612; P<0.0001) from baseline to 8th week in all the groups. Student's t test done for detecting a difference at specific time intervals showed statistically significant (P<0.0001) decrease in plaque score in group B compared to group A and group C, respectively, from 2nd to 8th week. Whereas, there was no statistical significant difference found when group A was compared with group C (P>0.05) from 2nd to 4th week. At the 6th and 8th weeks, there was significant difference (P<0.05) between group A and group C [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of plaque scores between the groups at various times intervals

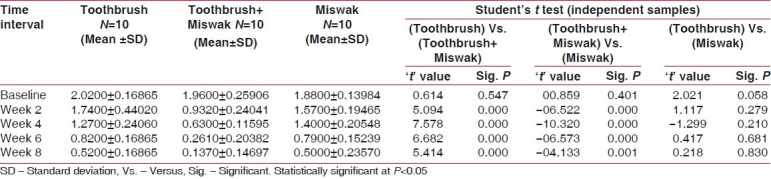

Comparison of gingival scores

Result obtained from repeated measure of ANOVA showed a highly significant decrease (F=11.981; P<0.0001) in mean gingival score from baseline to 8th week in all the groups. Student's t test showed statistically significant difference (P<0.05), when group B was compared with groups, A and C respectively. The difference was not significant when group A was compared with group C (P>0.05) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of gingival scores between the groups at various times intervals

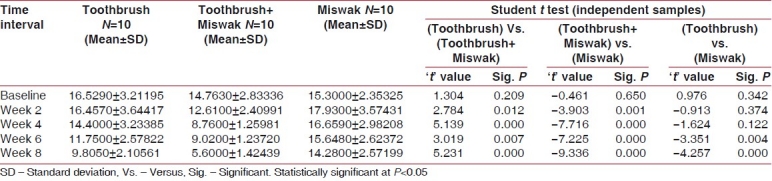

Comparison of percentage of area covered by stained plaque

Analysis done by results repeated measure of ANOVA showed that there was highly significant reduction (F=4.942; P<0.0001) in stained plaque area from baseline to 8th week in all the groups. Student's t test showed statistically significant (P<0.05) reduction of gingival score in group B, when compared with group A and group C, respectively. The difference was not significant, when group A was compared with group C (P>0.05) until 4th week. Further at the 6th and 8th week, the difference between the groups, A and C, was significant (P<0.05) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of percentage of area covered by stained plaque groups at various time intervals

DISCUSSION

Current study was designed to investigate the clinical therapeutic effect of miswak as an adjunct to tooth brushing method in the treatment of chronic gingivitis. The selection of miswak from the Salvadora persica tree for the present study was based on number of factors. The use of miswak is most common in the Middle East region and in the Indian subcontinent, its taste is acceptable,[5] it is inexpensive, and has been reported to have anti-plaque and many therapeutic pharmacological properties.[5–8]

There are studies[4–8] on the comparison of toothbrushes and miswak for plaque removal. Reports on the oral health of miswak users are contradictory and published literatures suggest that its therapeutic role in oral health needs to be verified before implementing into general practice of dentistry.

Current dental literature[14–16] describes several clinical indices and methods for measuring plaque and gingival inflammation, both quantitatively and qualitatively. The indices used to measure the accumulation of dental plaque and gingival inflammation are usually based on subjective estimations of the plaque-covered areas of the tooth surface and inflammatory changes of gingiva.[16] However, these indices on an ordinal scale are visual determinations resulting in data of less sensitivity. Photogrammetric techniques giving measurements in an interval scale have therefore been used to obtain more accurate measurements of the plaque area.[17]

The results of the present study showed that there was a significant reduction in plaque score and improvement in gingival health after the use of miswak as an adjunct to tooth brushing method. The miswak stick when not used as adjunct to tooth brush was not effective as the conventional toothbrush in reducing plaque until 4th week. Later at the 6th and 8th week, there was significant difference in plaque score in toothbrush user compared to miswak user. This initial reduction in the plaque score among the miswak users could be due to Hawthorne effect.[18] The Hawthorne effect is a form of reactivity, whereby subjects improve or modify an aspect of their behavior being experimentally measured simply in response to the fact that they are being studied, but not in response to any particular experimental manipulation.[18] The effect might have resulted from subject's initial excitement of using a new product (miswak) and trying to get a good result out of their use. After some time, as the weeks progressed, there could be a probability that the subjects lost their interest in using the miswak effectively. On the other hand, toothbrush is a part of routine oral hygiene procedure and is being practiced by individuals since the eruption of first dentition in the oral cavity. The subjects under toothbrush group used it effectively until the completion of the study.

Various controversial reports on the mechanical cleansing efficacy of the miswak have been published. Previous studies have revealed that higher plaque and gingival bleeding in chewing stick users as compared with toothbrush users.[10] Studies have also revealed that poor oral hygiene with those using chewing sticks may be a reflection of poor techniques.[10,11] Furthermore, the difference in topographic design of handles and bristles of miswak stick might be other reason of poor plaque control in miswak users. Studies have revealed that miswak bristles are not similar to the toothbrush bristles that are used to remove plaque from the tooth surfaces mechanically.[19] Unlike a conventional toothbrush, the bristles of the miswak lie in the same long axis as its handle.[10,11,19] The angulations in the toothbrush enable it to adapt more easily to the distal tooth surfaces, particularly on the posterior teeth. However, the techniques employed for removing plaque mechanically from outer surface and interproximal sites are similar with the toothbrush and the chewing stick, e.g., vertical and horizontal brushing.[20,21] These techniques primarily depend upon the people's attitudes, knowledge, and manual dexterity.[20] These mechanical differences were evident in our result also, and miswak bristles were not as effective as tooth brush bristles on outer surface area as well as interproximal area. These findings suggest that mechanically, miswak when not used in conjunctions to tooth brushes is not as effective as toothbrushes in cleaning the tooth surfaces.

In the present study, a standardized design was developed to minimize the effects of other variables, which could affect plaque control, including type of toothbrush and/or chewing stick (miswak), frequency of tooth brushing and/or miswak, and the technique of tooth brushing and/or miswak. The study condition was standardized by instructing all subjects on how to use the identical conventional toothbrushes and chewing sticks under direct supervision of investigator. Furthermore, all participants were issued with identical conventional toothbrushes and fresh chewing sticks of fairly uniform length.

Digital image analysis of plaque coverage was done for anterior region of dentition. Studies have revealed that in anterior region, the strokes and bristle angulations remain the same in both toothbrush and miswak stick and differ to great extent in posterior dentition.[20] Thus, an attempt was made to measure the covered plaque area from matched mechanical cleansing procedure in anterior dentition, which was not possible in posterior dentition.

Our result showed a beneficial effect of miswak on gingival health when used as an adjunct to tooth brushing method. This change could be attributed to the effect of different therapeutic components reported in the extract of miswak. Mentioned therapeutic components have been shown to beneficially influence the gingival health and plaque inhibition in various in vitro and in vivo studies.[7,22–28]

Silica in miswak acts as an abrasive material to remove plaques and stains.[7] Tannins (tannic acid) exert an astringent effect on the mucous membrane, thus reducing the clinically detectable gingivitis.[7,21,22] Alkaloids exert a bactericidal effect and stimulatory action on the gingiva.[23] Essential (volatile) oils possess characteristic aroma and exert carminative, antiseptic action.[7,21,24] The sulphur compounds have a bactericidal effect.[7,25,26] Vitamin C helps in the healing and repair of tissues.[7] Sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), NaHCO3, has mild abrasive properties and has a mild germicidal action.[25–27] High concentrations of chloride inhibit calculus formation.[28] These therapeutic findings of previous studies could be the reason for improved gingival health in the present study.

In the present study, subjects were advised to use freshly prepared miswak stick at indicated time interval. Previous studies have revealed that freshly prepared miswak sticks have no cytotoxic effect on periodontal tissue.[29] However, the same plant used even after 24 hours does contain harmful cytotoxic components and has potential to damage periodontal cells.[29] Based on these findings, we recommended cutting the used portion of the miswak after it has been used for one day and preparing a fresh part for the next use.

In the present study, miswak stick was used instead of miswak extract in mouthwash or toothpaste form assuming that miswak stick will provide both the mechanical and chemical effect supported by previous published literatures.[19–28] Our results showed beneficial chemical therapeutic action of miswak stick juice on gingival health, which was extracted on chewing miswak stick. No mechanical beneficial effect was observed when compared with toothbrush. Our results are in agreement with a controlled study,[30] where it was reported that powdered miswak if used with a mechanically proper device i.e. toothbrush, will give better results than miswak sticks alone or commercial toothpowder on gingival health. Presently, many commercial preparations are available in market as toothpaste, but no preparation presently exists in the form of mouthwash or in-office therapeutic medicament in the market. Thus, in future, well-controlled studies are required to evaluate miswak based therapeutic medicament, which can be used in treatment of mild to moderate gingival diseases.

CONCLUSION

Our results showed significant improvement in plaque score and gingival health when miswak was used as an adjunct to tooth brushing. Our findings clearly indicate that miswak cannot replace the toothbrush, but can be used an adjunct to toothbrush, utilizing the mechanical efficacy of toothbrush and chemical effects of miswak. Henceforth, in future, a well-designed study is required to ascertain the efficacy of miswak or miswak extract in the treatment of gingival diseases.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Page RC, Kornman KS. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis.An introduction. Periodontol. 2000;1997(14):9–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischman S. The history of oral hygiene products: How far have we come in 6000 years? Periodontol. 2000;1997(15):7–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu CD, Darout IA, Skaug N. Chewing sticks: Timeless natural toothbrushes for oral cleansing. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36:275–84. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.360502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almas K. Miswak (chewing stick) and its role in oral health. Postgraduate Dentist. 1993;3:214–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoory T. The use of chewing sticks in preventive oral hygiene. Clin Prev Dent. 1983;5:11–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhtar M, Ajmal M. Significance of chewing sticks (Miswak) in oral hygiene from a pharmacological viewpoint. J Pak Med Assoc. 1981;4:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farooqi MIH, Srivastava JG. The toothbrush tree (Salvadora persica) Quart J Crude Drug Res. 1968;8:1297–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Mostehy MR, Al-Jassem AA, Al-Yassin IA, El-Gindy AR, Shoukry E. Miswak as an oral health device. Preliminary chemical and clinical evaluation. Hamdard. 1983;26:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman S, Mosha HJ. Relationship between habits and dental health among rural Tanzanian children. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:317–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gazi M, Saini T, Ashri N, Lambourne A. Meswak chewing stick versus conventional tooth- brush as an oral hygiene aid. Clin Prev Dent. 1990;12:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oral health surveys. Basic methods. Geneva: WHO; 1997. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Obaida MI, Al-Essa MA, Asiri AA, Al-Rahla AA. Effectiveness of a 20% Miswak extract against a mixture of Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:640–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1907;38:610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quigiey G, Hein J. Comparative cleansing efficiency of manual and power brushing. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:26–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turesky S, Giimore ND, Glickman L. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of vitamin C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gazi M. Photographic plaque assessment of the antiplaque properties of Sanguinarine and chlor-hexidine. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:106–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wickstrom G, Bendix T. The “Hawthorne effect”–what did the original Hawthorne studies actually show.? Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:363–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton MR, Addy M. Chewing sticks versus toothbrushes in west Africa.A pilot study. Clin Prev Dent. 1989;11:11–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almas K, Al-Lafi T. The natural toothbrush. World Health Forum. 1995;16:206–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorner WG. Active substances from African and Asian natural toothbrushes. Chemische Rundschau. 1981;34:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almas K, Al-Bagieh N, Akpata ES. In vitro antibacterial effect of freshly cut and 1-month-old Miswak extracts. Biomedical Lett. 1997;56:145–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raed I, Al Sadhan, Khalid Alma. Miswak (chewing Stick): A cultural and scientific heritage. Saudi Dental J. 1999;11:80–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gazi Ml, Davies TJ, Al-Bagieh N, Cox SW. The immediate and medium-term effects of Meswak on the composition of mixed saliva. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:113–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant J. Miswak-toothbrushes that grow on trees. Todays FDA. 1990;2:6D. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abo Al-Samh D, Al-Bagieh N. A study of antibacterial activity of the miswak extract in vitro. Biomedical Lett. 1996;53:225–38. [Google Scholar]

- 27.AI-Lafi T, Ababneh H. The effect of the extract of the Miswak (chewing sticks) used in Jordan and the Middle East on oral bacteria. Int Dent J. 1995;45:218–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mustafa MH, Abd-el Al MM, Abo-el Fadl-KM. Reduced plaque formation by Miswak -based mouthwash. Egypt Dent J. 1987;33:375–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abo Al-Samh D, Al-Nazhan S. In vitro study of the cytotoxicity of the miswak ethanolic extract. Saudi Dental J. 1997;9:125–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attar ZA. The miswak - natures toothbrush. Bull Hist Dent. 1979;27:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]