Abstract

Objective:

Although the medical home is promoted by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Affordable Care Act, its impact on children without special health care needs is unknown. We examined whether the medical home is associated with beneficial health care utilization and health-promoting behaviors in this population.

Methods:

This study was a secondary data analysis of the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. Data were available for 70 007 children without special health care needs. We operationalized the medical home according to the National Survey of Children’s Health design. Logistic regression for complex sample surveys was used to model each outcome with the medical home, controlling for sociodemographic characteristics.

Results:

Overall, 58.1% of children without special health care needs had a medical home. The medical home was significantly associated with increased preventive care visits (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 1.32 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.22–1.43]), decreased outpatient sick visits (aOR: 0.71 [95% CI: 0.66–0.76), and decreased emergency department sick visits (aOR: 0.70 [95% CI: 0.65–0.76]). It was associated with increased odds of “excellent/very good” child health according to parental assessment (aOR: 1.29 [95% CI: 1.15–1.45) and health-promoting behaviors such as being read to daily (aOR: 1.46 [95% CI: 1.13–1.89]), reported helmet use (aOR: 1.18 [95% CI: 1.03–1.34]), and decreased screen time (aOR: 1.12 [95% CI: 1.02–1.22]).

Conclusions:

For children without special health care needs, the medical home is associated with improved health care utilization patterns, better parental assessment of child health, and increased adherence with health-promoting behaviors. These findings support the recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Affordable Care Act to extend the medical home to all children.

KEY WORDS: patient-centered care, pediatrics, health policy, Outcome Assessment (Health Care), medical home

What’s Known On This Subject:

The medical home is associated with beneficial outcomes in children with special health care needs and in the entire pediatric population. It is unknown if it benefits the majority of the pediatric population (ie, children without special health care needs).

What This Study Adds:

This study is the first to demonstrate an association between the medical home and beneficial health care utilization, child health, and health-promoting behavior outcomes in children without special health care needs.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) defines the medical home as a model of care that is “accessible, family-centered, continuous, comprehensive, coordinated, compassionate and culturally effective” and promotes it as the source of primary care for all children.1 Although it was conceived for all children, the medical home was initially promoted nationally by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s Division of Services for Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN)1–4 and has been studied primarily in that population. Among CSHCN, it is associated with numerous positive health outcomes, such as decreased emergency department (ED) utilization5–7 and hospitalization rates.8–10 However, it remains unknown whether the medical home is beneficial for the majority of the pediatric population (ie, children without special health care needs). The need to address this question is emphasized by the recent enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordability Act, which promotes the “patient-centered medical home” for all patients.11

A recent study found an association between the medical home and both increased preventive care visits and decreased unmet needs in a nationally representative sample of the entire pediatric population.12 However, this study included children with and without special health care needs. To our knowledge, no studies to date have investigated children without special health care needs as the sole group. In addition, studies have focused primarily on health care utilization outcomes. However, those short-term outcomes, such as ED utilization and hospitalization, are infrequent in healthy children. Measurement of the more common healthy behaviors included in the AAP’s Bright Futures health supervision guidelines would also match the intent of the medical home model to promote all aspects of a child’s health and well-being.1

We studied the association between having a medical home and health care utilization, child health, and health-promoting behavior outcomes using a nationally representative dataset. We hypothesized that having a medical home would be associated with better outcomes for children without special health care needs.

Methods

Data Set

This study was a secondary data analysis of the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). The NSCH was designed by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics. The NSCH was conducted over 2 years in English and Spanish via random-digit dialing using the State and Local Area Integrated Telephone Survey mechanism, and collected information on 102 353 children aged <18 years nationally.13 An adult respondent in each participating household was asked 295 questions grouped into 11 sections regarding a single randomly selected child in the household. Sections included questions regarding the following domains: demographic information, health and functional status, health insurance coverage, health care access and utilization, the medical home, family functioning, parental health, and neighborhood characteristics. The survey was clustered at the household level and stratified at the state level. Weighting based on gender and telephone-ownership distribution was derived from national census data.13

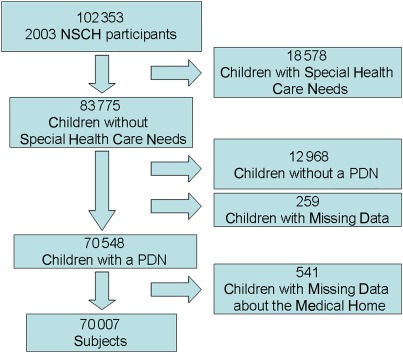

Study Population

The 2003 NSCH collected data on 102 353 children. Because the study’s focus was on children without special health care needs, we excluded CSHCN. This status was determined by the response to questions comprising the externally validated Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative’s CSHCN Screener.14 Approximately 18% of the original sample were CSHCN (n = 18 578). To focus exclusively on the impact of a medical home among children with a regular provider of care, we only analyzed data from children with a personal doctor or nurse (PDN). More than 15% of children without special health care needs did not have a PDN (n = 12 968) and were excluded from all analyses. Data regarding the presence of a medical home were not available for 541 of the remaining children, leaving a study sample of 70 007 (68.4% of the original sample; Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Subject selection.

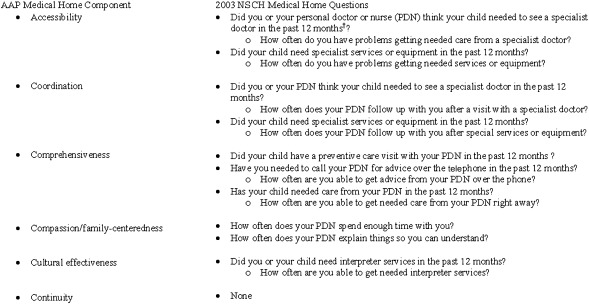

Medical Home

The presence of a medical home was established through a series of questions in the survey designed to measure 6 of the 7 key components of the medical home as defined by the AAP (Fig 2).1 Our definition was consistent with the dataset’s protocol; previous investigators have used this same definition.15–17

FIGURE 2.

Operationalization of the medical home.

Questions for each component of the medical home were coded on an ordinal scale assessing frequency of access (never, sometimes, usually, or always). These ordinal responses were re-coded as numerical values representing percentages (“never” = 0, “sometimes” = 25, “usually” = 75, and “always” = 100) and were averaged across the questions. The component was considered present if the average was ≥67 (ie, usually or more frequently).

The accessible, coordinated, and comprehensive care components were first assessed via a dichotomous screening question to establish whether further questioning was needed. Affirmative answers to a screening question triggered additional ordinal-scaled questions. A given component was considered present if the response to the screening question was “no” or the average of the ordinal-scaled questions was usually or more frequently.

Assessment of the comprehensive care component also included a single dichotomous question on preventive care visits in the previous 12 months. For children aged ≥24 months, the question was adjusted to inquire about the previous 24 months. Of note, this single question was excluded from the definition of the medical home when we examined the presence of a preventive care visit as a health care utilization outcome.

Compassion and family-centeredness were grouped together and assessed through 2 questions coded on an ordinal scale. Cultural effectiveness was assessed through a single ordinal-scaled question. The continuous care component of the medical home was not measured in this survey.

The medical home was only considered to exist if all 6 components were present.

Health Care Utilization, Child Health, and Health-Promoting Behavior Outcomes

Health care utilization outcomes previously demonstrated to be associated with the medical home in other study populations were included (preventive visits,12 outpatient sick visits, and ED sick visits7), along with child health outcomes (parental assessment of global health18,19 and missed days of school due to illness or injury) and health-promoting behaviors endorsed by Bright Futures20 and considered evidence based (frequency of being read to daily,21 frequency of obtaining sufficient sleep nightly,22 helmet usage,23 average school day screen time,24–26 and history of ever being breastfed27,28).

We used variables as defined and reported by the designers of the 2003 NSCH (see Appendix 1). We constructed the variables ED sick visits and average school day screen time from the reported variables. To derive the number of ED sick visits, we subtracted the number of ED visits due to an accident, injury, or poisoning from the total number of visits. To derive average school day screen time, we added the average number of hours spent using the computer for purposes other than school work to the average number of hours spent watching television and videos or playing video games. We compressed reported categorical variables into dichotomous variables.13 To ensure clinical relevance, we used the AAP-recommended <2 hours of screen time per day as the cutoff for average school day screen time20 and the national average of 3 missed days of school per year due to acute illness as the cutoff for missed days of school.29

Data Analysis

Bivariate analyses between the presence of a medical home and sociodemographic characteristics were performed. For continuous variables, the 2-sided t test was used to evaluate the equivalence of the mean between those subjects with and without a medical home. Means and SEs, as well as P values, were calculated. For categorical variables, the χ2 test of independence was used to evaluate the association between the medical home and covariates. Frequencies and percentages, as well as P values, were calculated. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Survey-specific SAS procedures were used to account for weighting, clustering, and stratification in the survey design (PROC SURVEYMEANS and PROC SURVEYFREQ).

Logistic regression models were used to assess the association between each health care utilization, child health, and health-promoting behavior outcome and the medical home, controlling for covariates. Each model was initially constructed with all sociodemographic covariates shown in bivariate analysis to be associated with the presence of a medical home, as well as those selected a priori due to demonstrated or theoretical clinical significance. For the health-promoting behavior outcomes, the presence of a preventive care visit in the previous 12 months was also entered into the regression model. Evaluation of the change in the crude effect estimate with and without each covariate was then used to determine which covariates to include in the final main-effects model. Interaction terms selected in a priori fashion were then individually introduced into the model and assessed in the same fashion (Appendix 2). A survey-specific SAS procedure was used to account for weighting, clustering and stratification in the survey design (PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC). A survey-specific procedure was also used to perform age-group analyses (0–1, 2–5, 6–11, and 12–17 years of age) of each outcome (the “domain” statement for PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as well as P values, were calculated for each model.

Statistical significance was defined as a P value <.05.

Institutional Review Board

The Boston University School of Medicine/Boston Medical Center Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt from human studies review.

Results

Of the 70 007 children without special health care needs included in the analysis, the majority had a medical home (58.1%; n = 40 678).

All of the sociodemographic characteristics with the exception of the subject’s gender were unevenly distributed between children with and without medical homes (Table 1). Children who received care within a medical home were more likely to be younger and non-Hispanic white. They were also more likely to speak English at home and to live in a 2-parent (biological/adoptive) family. Children living in households with income ≥400% federal poverty level (FPL) had twice the odds of having a medical home than children living below the FPL. Similarly, children with a parent who was educated beyond high school were more than twice as likely to have a medical home than those whose parents did not complete high school. Having a medical home was positively associated with having current health insurance coverage and a preventive care visit in the previous 12 months.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Sociodemographic Characteristics and Preventive Visits Among Children With and Without Medical Homes

| Characteristic | All Children | Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 70 007) | (n = 40 678) | (n = 29 329) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 49.3 (0.3) | 49.1 (0.4) | 49.6 (0.5) | Reference |

| Female | 50.7 (0.3) | 50.9 (0.4) | 50.4 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| Age, mean ± SE, y | 8.2 ± 0 | 7.5 ± 0 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | — |

| Age, y | ||||

| 0–1 | 12.6 (0.2) | 16.5 (0.3) | 7.5 (0.3) | Reference |

| 2–5 | 23.7 (0.3) | 26.6 (0.4) | 19.8 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)a |

| 6–11 | 32.3 (0.3) | 29.0 (0.4) | 36.5 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.3–0.4)a |

| 12–17 | 31.5 (0.3) | 27.9 (0.4) | 36.2 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.3–0.4)a |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 15.1 (0.3) | 11.9 (0.3) | 19.2 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6)a |

| Non-Hispanic white | 64.6 (0.3) | 69.3 (0.4) | 58.3 (0.5) | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 13.0 (0.3) | 11.8 (0.3) | 14.6 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8)a |

| Non-Hispanic, multiracial | 2.9 (0.1) | 2.9 (0.1) | 2.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 4.4 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.6–0.9)a |

| Household income as % of the FPL | ||||

| 0%–99% | 13.9 (0.3) | 11.1 (0.3) | 17.7 (0.5) | Reference |

| 100%–199% | 21.5 (0.3) | 19.0 (0.4) | 24.7 (0.5) | 1.2 (1.1–1.4)a |

| 200%–399% | 34.8 (0.3) | 36.0 (0.4) | 33.2 (0.5) | 1.6 (1.5–1.8)a |

| ≥400% | 29.8 (0.3) | 33.9 (0.4) | 24.4 (0.4) | 2.0 (1.8–2.2)a |

| Highest attained parental education | ||||

| <High school | 5.9 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.2) | 8.1 (0.4) | Reference |

| High school | 24.4 (0.3) | 21.3 (0.4) | 28.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7)a |

| >High school | 69.8 (0.3) | 74.5 (0.4) | 63.5 (0.5) | 2.1 (1.8–2.5)a |

| Primary language spoken in the home | ||||

| English | 89.5 (0.3) | 92.8 (0.3) | 85.1 (0.5) | Reference |

| Any other language | 10.5 (0.3) | 7.2 (0.3) | 14.9 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.4–0.6)a |

| Current health insurance coverage | ||||

| No | 6.4 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.2) | 8.8 (0.3) | Reference |

| Yes | 93.6 (0.2) | 95.5 (0.2) | 91.2 (0.3) | 1.7 (1.5–2.0)a |

| Family structure | ||||

| 2-parent (biological/adoptive) | 67.8 (0.3) | 71.8 (0.4) | 62.5 (0.5) | Reference |

| 2-parent (step) | 7.7 (0.2) | 7.0 (0.2) | 8.6 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.7–0.8)a |

| Single mother | 20.5 (0.3) | 18.0 (0.4) | 23.9 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.6–0.7)a |

| Other | 4.0 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7)a |

| No. of preventive visits in the past 12 mo | ||||

| 0 | 20.5 (0.3) | 18.3 (0.3) | 25.5 (0.6) | Reference |

| ≥1 | 79.5 (0.3) | 81.7 (0.3) | 74.5 (0.6) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6)a |

Data are presented as % (SE), unless otherwise indicated.

Significant at P < .05.

The majority of the health care utilization outcomes were beneficially associated with the presence of a medical home (Table 2). These results were largely unchanged after controlling for covariates. Children with medical homes had increased odds of having had a preventive care visit in the previous 12 months (adjusted [aOR]: 1.32 [95% CI: 1.22–1.43]). They also had decreased odds of having had an outpatient sick visit (aOR: 0.71 [95% CI: 0.66–0.76]) and decreased odds of having had an ED sick visit (aOR: 0.70 [95% CI: 0.65–0.76]).

TABLE 2.

Association of a Medical Home With Health Care Utilization Outcomes Among Children Without Special Health Care Needs

| Health Care Utilization Outcomes | Children Without Special Health Care Needs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)a | ||

| Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | |||

| Preventive visitsb | ||||

| ≥1 | 81.7 (0.3) | 74.5 (0.6) | 1.53 (1.43–1.64)* | 1.32 (1.22–1.43)* |

| 0 | 18.3 (0.3) | 25.5 (0.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Outpatient sick visits | ||||

| ≥1 | 67.7 (0.4) | 71.5 (0.6) | 0.83 (0.78–0.89)* | 0.71 (0.66–0.76)* |

| 0 | 32.3 (0.4) | 28.5 (0.6) | Reference | Reference |

| ED sick visits | ||||

| ≥1 | 16.0 (0.3) | 21.0 (0.5) | 0.71 (0.66–0.77)* | 0.70 (0.65–0.76)* |

| 0 | 84.0 (0.3) | 79.0 (0.5) | Reference | Reference |

Adjusted for gender, age, race and ethnicity, household income as % of the FPL, highest attained parental education, primary language spoken in the home, current insurance coverage, and family structure.

Medical home status defined without number of preventive visits with the PDN in the past 12 months.

Significant at P < .05.

Children with medical homes had greater odds of receiving a parental assessment of “excellent/very good” compared with “good/fair/poor” global health (aOR: 1.29 [95% CI: 1.15–1.45]). There was no difference between the groups for missed days of school (aOR: 1.03 [95% CI: 0.95–1.11]) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Association of a Medical Home With Child Health Outcomes Among Children Without Special Health Care Needs

| Child Health Outcomes | Children Without Special Health Care Needs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)a | ||

| Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | |||

| Parental assessment of global health | ||||

| Excellent/very good | 93.0 (0.2) | 87.1 (0.4) | 1.93 (1.73–2.15)* | 1.29 (1.15–1.45)* |

| Good/fair/poor | 7.0 (02) | 12.9 (0.4) | Reference | Reference |

| Missed days of school in the past 12 mo | ||||

| >3 | 32.1 (0.5) | 31.0 (0.6) | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 1.03 (0.95–1.11) |

| ≤3 | 67.9 (0.5) | 69.0 (0.6) | Reference | Reference |

Adjusted for gender, age, race and ethnicity, household income as % of the FPL, highest attained parental education, primary language spoken in the home, current insurance coverage, and family structure.

Significant at P < .05.

Table 4 shows the association, both unadjusted and adjusted, between having a medical home and health-promoting behaviors. Children with medical homes had significantly greater odds of being read to daily (aOR: 1.46 [95% CI: 1.13–1.89]), getting sufficient sleep daily (aOR: 1.56 [95% CI 1.20–2.04]), always using a helmet (aOR: 1.18 [95% CI: 1.03–1.34]), and watching <2 hours of screen time daily (aOR: 1.12 [95% CI: 1.02–1.22]). Although they were more likely to have ever been breastfed in unadjusted analysis, this was not significant after controlling for covariates (aOR: 1.00 [95% CI: 0.88–1.14]).

TABLE 4.

Association of a Medical Home With Health-Promoting Behavior Outcomes Among Children Without Special Health Care Needs

| Health-Promoting Behavior Outcomes | Children Without Special Health Care Needs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)a | ||

| Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | |||

| Read to | ||||

| Daily | 51.9 (0.7) | 42.1 (1.0) | 1.68 (1.38–2.04)* | 1.46 (1.13–1.89)* |

| Sometimes | 41.8 (0.6) | 49.4 (1.0) | 1.15 (0.94–1.41) | 1.16 (0.90–1.50) |

| Never | 6.3 (0.4) | 8.5 (0.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Sufficient sleep | ||||

| Daily | 68.9 (0.5) | 69.6 (0.5) | 1.50 (1.19–1.87)* | 1.56 (1.20–2.04)* |

| Sometimes | 29.1 (0.5) | 27.4 (0.5) | 1.60 (1.28–2.02)* | 1.43 (1.10–1.88)* |

| Never | 2.0 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.2) | Reference | Reference |

| Helmet usage | ||||

| Always | 43.8 (0.6) | 35.8 (0.7) | 1.61 (1.47–1.77)* | 1.18 (1.03–1.34)* |

| Usually | 16.2 (0.5) | 14.2 (0.5) | 1.50 (1.34–1.68)* | 1.11 (0.94–1.30) |

| Sometimes | 17.7 (0.5) | 20.5 (0.5) | 1.13 (1.02–1.26)* | 1.10 (0.95–1.27) |

| Never | 22.3 (0.5) | 29.4 (0.6) | Reference | Reference |

| Average school day screen time, h | ||||

| <2 | 68.4 (0.4) | 55.8 (0.5) | 1.72 (1.63–1.82)* | 1.12 (1.02–1.22)* |

| ≥2 | 31.6 (0.4) | 44.2 (0.5) | Reference | Reference |

| Breastfed ever | ||||

| Yes | 75.2 (0.5) | 70.9 (0.9) | 1.25 (1.13–1.38)* | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) |

| No | 24.8 (0.5) | 29.1 (0.9) | Reference | Reference |

Adjusted for gender, age, race and ethnicity, household income as % of the FPL, highest attained parental education, primary language spoken in the home, current insurance coverage and family structure, and number of preventive visits in the previous 12 months.

Significant at P < .05.

In subgroup analysis stratifying according to age, children aged 0 to 1 year had the strongest association between a medical home and both increased preventive care visits (aOR: 1.67 [95% CI: 1.08–2.57]) and global health being excellent/very good (aOR: 1.44 [95% CI: 1.02–2.04]). The medical home was no longer significantly associated with increased parental global health rating for children aged 2 to 5 years. School-aged children (6–11 years) had the strongest association between a medical home and fewer ED sick visits (aOR: 0.64 [95% CI: 0.55–0.74]) (Table 5). Adolescents (12–17 years of age) had the strongest association between a medical home and fewer outpatient sick visits (aOR: 0.67 [95% CI: 0.59–0.75]). There remained no association with missed days of school stratified by age. Differences across groups also existed among health behavior outcomes, but no pattern emerged.

TABLE 5.

Association of a Medical Home With Health Care Utilization, Child Health, and Health-Promoting Behavior Outcomes Among Children Without Special Health Care Needs by Age Group

| Variable | Children Without Special Health Care Needs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children Aged 0–1 y | Children Aged 2–5 y | Children Aged 6–11 y | Children Aged 12–17 y | |||||||||

| % (SE) | aOR (95% CI)a | % (SE) | aOR (95% CI)a | % (SE) | aOR (95% CI)a | % (SE) | aOR (95% CI)a | |||||

| Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | Children With a Medical Home | Children Without a Medical Home | |||||

| Health care utilization outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Preventive visitsb | ||||||||||||

| ≥1 | 96.7 (0.4) | 91.6 (1.1) | 1.67 (1.08–2.57)* | 88.5 (0.5) | 82.8 (1.0) | 1.35 (1.12–1.63)* | 74.0 (0.7) | 68.7 (1.1) | 1.24 (1.10–1.41)* | 77.3 (06) | 70.3 (0.9) | 1.38 (1.23–1.55)* |

| 0 | 3.3 (0.4) | 8.4 (1.1) | Reference | 11.5 (0.5) | 17.2 (1.0) | Reference | 26.0 (0.7) | 31.3 (1.1) | Reference | 22.7 (0.6) | 29.7 (0.9) | Reference |

| Outpatient sick visits | ||||||||||||

| ≥1 | 69.2 (0.9) | 75.9 (1.7) | 0.73 (0.59–0.90)* | 76.5 (0.7) | 77.4 (1.3) | 0.84 (0.71–0.99)* | 68.8 (0.8) | 73.8 (1.0) | 0.73 (0.64–0.83)* | 57.1 (0.8) | 64.4 (1.0) | 0.67 (0.59–0.75)* |

| 0 | 30.8 (0.9) | 24.1 (1.7) | Reference | 23.5 (0.7) | 22.6 (1.3) | Reference | 31.2 (0.8) | 26.2 (1.0) | Reference | 42.9 (0.8) | 35.6 (1.0) | Reference |

| ED sick visits | ||||||||||||

| ≥1 | 22.5 (0.9) | 35.3 (1.8) | 0.69 (0.56–0.84)* | 19.3 (0.7) | 24.4 (1.2) | 0.76 (0.64–0.89)* | 12.8 (0.6) | 19.1 (0.8) | 0.64 (0.55–0.74)* | 12.2 (0.5) | 16.9 (0.7) | 0.70 (0.60–0.80)* |

| 0 | 77.5 (0.9) | 64.7 (1.8) | Reference | 80.7 (0.7) | 75.6 (1.2) | Reference | 87.2 (0.6) | 80.9 (0.8) | Reference | 87.8 (0.5) | 83.1 (0.7) | Reference |

| Child health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Parental assessment of global health | ||||||||||||

| Excellent/very good | 92.9 (0.7) | 85.0 (1.3) | 1.44 (1.02–2.04)* | 93.0 (0.5) | 87.4 (0.8) | 1.23 (0.96–1.58) | 93.2 (0.5) | 87.7 (0.7) | 1.33 (1.08–1.65)* | 92.8 (0.4) | 86.9 (0.7) | 1.33 (1.10–1.60)* |

| Good/fair/poor | 7.1 (0.7) | 15.0 (1.3) | Reference | 7.0 (0.5) | 12.6 (0.8) | Reference | 6.8 (0.5) | 12.3 (0.7) | Reference | 7.2 (0.4) | 13.1 (0.7) | Reference |

| Missed days of school in the past 12 mo | ||||||||||||

| >3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 32.8 (0.8) | 30.6 (0.8) | 1.07 (0.96–1.19) | 31.4 (0.8) | 31.4 (0.8) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.10) |

| ≤3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 67.2 (0.8) | 69.4 (0.8) | Reference | 69.6 (0.8) | 68.6 (0.8) | Reference |

| Health-promoting behavior outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Read to | ||||||||||||

| Daily | 44.1 (1.0) | 36.3 (1.7) | 1.38 (0.99–1.94) | 56.8 (0.8) | 44.3 (1.2) | 1.78 (1.13–2.79)* | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sometimes | 43.2 (1.0) | 46.3 (1.8) | 1.17 (0.85–1.63) | 40.9 (0.8) | 50.5 (1.2) | 1.35 (0.86–2.11) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Never | 12.7 (0.8) | 17.5 (1.4) | Reference | 2.3 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.6) | Reference | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sufficient sleep | ||||||||||||

| Daily | — | — | — | — | — | — | 75.9 (0.7) | 77.1 (0.7) | 1.00 (0.60–1.69) | 61.7 (0.8) | 62.1 (0.8) | 1.68 (1.23–2.29)* |

| Sometimes | — | — | — | — | — | — | 23.1 (0.7) | 21.7 (0.7) | 0.97 (0.57–1.64) | 35.3 (0.8) | 33.1 (0.8) | 1.49 (1.09–2.05)* |

| Never | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.2) | Reference | 3.0 (0.3) | 4.8 (0.5) | Reference |

| Helmet usage | ||||||||||||

| Always | — | — | — | — | — | — | 53.0 (0.8) | 43.3 (0.9) | 1.17 (0.96–1.44) | 31.8 (0.9) | 25.9 (0.9) | 1.19 (1.00–1.42)* |

| Usually | — | — | — | — | — | — | 17.9 (0.6) | 15.5 (0.6) | 1.16 (0.91–1.48) | 13.9 (0.7) | 12.5 (0.7) | 0.99 (0.79–1.23) |

| Sometimes | — | — | — | — | — | — | 16.1 (0.6) | 20.4 (0.7) | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) | 19.7 (0.8) | 20.7 (0.8) | 1.19 (0.98–1.44) |

| Never | — | — | — | — | — | — | 13.0 (0.6) | 20.8 (0.7) | Reference | 34.7 (0.8) | 40.9 (1.0) | Reference |

| Average school day screen time, h | ||||||||||||

| <2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 51.4 (0.8) | 46.0 (0.9) | 1.14 (1.00–1.30) | 37.4 (0.8) | 32.3 (0.8) | 1.124 (1.00–1.28) |

| ≥2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 48.6 (0.8) | 54.0 (0.9) | Reference | 62.6 (0.8) | 67.7 (0.8) | Reference |

| Breastfed ever | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 77.3 (0.8) | 74.9 (1.5) | 0.98 (0.79–1.22) | 73.9 (0.7) | 69.4 (1.1) | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| No | 22.7 (0.8) | 25.1 (1.5) | Reference | 26.1 (0.7) | 30.6 (1.1) | Reference | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Adjusted for gender, age, race and ethnicity, household income as % of the FPL, highest attained parental education, primary language spoken in the home, current insurance coverage, and family structure.

Medical home status without number of preventive visits in the past 12 months.

Significant at P < .05.

Discussion

Our study found a beneficial relationship between numerous health outcomes and the medical home in children without special health care needs. Although some of the effect sizes were modest, the health care utilization outcomes (preventive visits, outpatient sick visits, and ED sick visits) were robust (∼30%).

Children without special health care needs compose the majority of the pediatric population (>80% in this national dataset). The AAP has long promoted the medical home for all children,4 and the Affordable Care Act of 2009 promotes the patient-centered medical home; this study provides further evidence supporting these policies. Our findings are significant given that studies to date have focused primarily on CSHCN. Although some studies have included all children, it was unclear if the positive associations found were due solely to the effect of CSHCN in the study populations, or if they exist independent of CSHCN.12,30–41 Our findings suggest that the benefits of the medical home for children without special health care needs mirror those experienced by CSHCN.

Our study broadened the outcomes measures assessed. Previous studies have focused on clinical outcomes such as ED utilization5,6,32,34,37 and immunizations.30,31,33,35–37,39–41 The medical home concept, however, is explicitly designed to provide care for all aspects of a child’s health and well-being.1 We therefore selected health-promoting behavior outcomes previously demonstrated to be positively associated with child health.21,23–28 The presence of a medical home was associated with health-promoting behaviors such as family reading, sleep hygiene, helmet use, and decreased screen time. Although the effects are modest, the near-universal reach of health care for children suggests that there may be a significant public health impact. We believe that future studies examining the impact of the medical home should consider reporting similar health-promoting behaviors.

Our findings have several implications for public policy and the delivery of primary care. Our study supports previous findings which suggest that having a medical home may decrease unnecessary child health care utilization (eg, ED visits), leading to overall health care savings. Studies have estimated that care inappropriately received in the ED costs 2 to 3 times as much as the same care in the appropriate setting.42,43 A reduction in ED utilization for sick visits of close to 30% would therefore represent a significant cost savings. Furthermore, our data demonstrated that preadolescents, who are more likely to have inappropriate ED utilization than adolescents or adults,44 may benefit the most from having a medical home. Thus, although further studies are needed, promoting the medical home among children without special health care needs presents a promising avenue for additional cost savings and improved health.

Our findings are consistent with those among the CSHCN and entire pediatric populations that disparities exist in children’s access to medical homes. We found that non-white children without special health care needs were less likely to have a medical home than white children. In addition, we found gradients with respect to socioeconomic status measures such as household income and parental education. Given the associations demonstrated in our study between the medical home and beneficial health care utilization patterns, increasing access to the medical home for these families may yield downstream reductions in other health care disparities.

The study has a number of limitations. First, the operationalization of the definition of the medical home is not validated. Although the definition has been agreed upon,45 measurement of it has not, which has prevented establishment of a validated questionnaire and limits comparison between studies. As used in our study, the definition of the medical home did not capture the continuity component defined by the AAP.1 In addition, the presence of a medical home was measured from the family’s perspective; this operationalization is therefore different from the systems-centered approach as espoused by the National Committee for Quality Assurance.46 However, this operationalization has been used by previous investigators who have analyzed this national dataset.15 Second, the data may not reflect the promotion of the medical home that has occurred since 2003. We chose these data instead of the 2007 NSCH as the latter did not measure ED and outpatient sick visits. Our data are the most recent available for these key outcome measures, and we therefore believe that our findings remain relevant to current policy and practice. Additional studies using more recent data, such as the forthcoming 2011 NSCH, will be useful. Third, the data were collected by self-report and were not validated, with the exception of CSHCN status.14 Fourth, this was a cross-sectional study, and therefore we cannot determine causality. Finally, although results were adjusted to account for the racial and socioeconomic disparities discussed here, it is possible that there were other unmeasured differences between the populations that may account for some of the differences attributed to medical home status. Further prospective studies examining the causal relationships between the medical home and health outcomes in children without special health care needs are needed.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that the medical home is associated with beneficial health care utilization, child health, and health-promoting behavior outcomes in children without special health care needs. Our findings strengthen the evidence base for the AAP’s recommendation that all children have a medical home. With the advent of federal legislation promoting the medical home for all children, it is increasingly important that studies further investigate this subject to better understand and improve health care for all children.

Acknowledgments

Dr Long was supported by the National Research Service Award grant 6 T32 HP 10263-01 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Tracey Wilkinson, MD, Hema Magge, MD, Sabrina Noel, PhD, Caroline Kistin, MD, and Leslie Bradford, MD, for contributions and thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Glossary

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- CSHCN

children with special health care needs

- ED

emergency department

- FPL

federal poverty level

- NSCH

National Survey on Children’s Health

- PDN

personal doctor or nurse

APPENDIX 1 Study Variables and Their Associated 2003 NSCH Question(s)

| Study Variable | Associated 2003 NSCH Question(s) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| • Gender | • Is [CHILD] male or female? |

| • Age | • Many of my questions are for children of certain ages. So, I’ll know which questions to ask, please tell me the [age/ages] of the [child/children] less than 18 years old living in this household. |

| • Race and ethnicity | • Is [CHILD] of Hispanic or Latino origin? |

| • Now, I'm going to read a list of categories. Please choose one or more of the following categories to describe [CHILD]’s race. Is [CHILD] white, Black or African American, American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander? | |

| • Household income | • Now I am going to ask you a few questions about your income. Please think about your total combined FAMILY income during (CATI: FILL LAST CALENDAR YEAR) for all members of the family. Include money from jobs, social security, retirement income, unemployment payments, public assistance, and so forth. Also, include income from interest, dividends, net income from business, farm, or rent, and any other money income received. Can you tell me that amount before taxes? |

| • Highest attained parental education | • What is the highest level of education attained by anyone in your household? |

| • Primary language spoken in the home | • What is the primary language spoken in your home? |

| • Current health insurance coverage | • Does [CHILD] have any kind of health care coverage, including health insurance, prepaid plans such as HMOs, or government plans such as Medicaid? |

| • Family structure | • Earlier you told me you are [CHILD]’s [mother/father]. Are you [CHILD]’s biological, adoptive, step, or foster [mother/father]? |

| • Earlier you told me you are [CHILD]’s [ANSWER TO S1Q02)]. [Other than yourself does/Does] [S.C]. have any (other) parents, or people who act as [his/her] parents, living here? | |

| • Presence of PDN | • A personal doctor or nurse is a health professional who knows your child well and is familiar with your child’s health history. This can be a general doctor, a pediatrician, a specialist doctor, a nurse practitioner, or a physician assistant. Do you have one or more persons you think of as [CHILD]’s personal doctor or nurse? |

| • Child with special health care needs status | • Does [CHILD] currently need or use medicine prescribed by a doctor, other than vitamins? |

| • Is [his/her] need for prescription medicine because of ANY medical, behavioral, or other health condition? | |

| • Is this a condition that has lasted or is expected to last 12 mo or longer? | |

| • Does [CHILD] need or use more medical care, mental health, or educational services than is usual for most children of the same age? | |

| • Is [his/her] need for medical care, mental health or educational services because of ANY medical, behavioral, or other health condition? | |

| • Is this a condition that has lasted oris expected to last 12 months or longer? | |

| • Is [CHILD] limited or prevented in any way in [his/her] ability to do the things most children of the same age can do? | |

| • Is [his/her] limitation in abilities because of ANY medical, behavioral, or other health condition? | |

| • Is this a condition that has lasted or is expected to last 12 mo or longer? | |

| • Does [CHILD] need or get special therapy, such as physical, occupational, or speech therapy? [SPECIAL THERAPY INCLUDES PHYSICAL, OCCUPATIONAL, OR SPEECH THERAPY. DO NOT INCLUDE PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPY.] | |

| • Is [his/her] need for special therapy because of ANY medical, behavioral, or other health condition? | |

| • Is this a condition that has lasted or is expected to last 12 mo or longer? | |

| • Does [CHILD] have any kind of emotional, developmental, or behavioral problem for which [he/she] needs treatment or counseling? | |

| • Has [his/her] emotional, developmental or behavioral problem lasted or is it expected to last 12 mo or longer? | |

| Health care utilization outcomes | |

| • Preventive visits | • [During the past 12 mo/Since [his/her] birth], how many times did [CHILD] see a doctor, nurse, or other health care professional for preventive medical care such as a physical exam or well-child check-up? |

| • Outpatient sick visits | • Excluding emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and well-child care, how many times [during the past 12 mo/Since [his/her] birth], did [he/she] see a doctor, nurse, or other health care professional for sick-child care? |

| • ED sick visits | • [During the past 12 mo/Since [his/her] birth], how many times did [CHILD] go to a hospital emergency department about [his/her] health? This includes emergency department visits that resulted in a hospital admission. |

| • How many emergency department visits were because of an accident, injury, or poisoning? | |

| Child health outcomes | |

| • Parental assessment of global health | • In general, how would you describe [CHILD] ’s health? Would you say [his/her] health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor? |

| • Missed days of school | • During the past 12 mo that is, since [FILL: CURRENT MONTH, 1 YEAR AGO] about how many days did [CHILD] miss school because of illness or injury? |

| Health-promoting behaviors | |

| • Frequency of being read to daily | • During the past week, how many days did you or other family members read stories to [CHILD]? |

| • Frequency of obtaining sufficient sleep nightly | • During the past week, on how many nights did [CHILD] get enough sleep for a child [his/her] age? |

| • Helmet usage | • How often does [he/she] wear a helmet when riding a bike, scooter, skateboard, roller skates, or rollerblades? Would you say never, sometimes, usually or always? |

| • Screen time | • On an average school day, about how many hours does [CHILD] use a computer for purposes other than schoolwork? |

| • On an average school day, about how many hours does [CHILD] usually watch TV, watch videos, or play video games? | |

| • History of ever being breastfed | • Was [CHILD] ever breastfed or fed breast milk? |

APPENDIX 2 Study Outcome Models Including Covariates, Interaction Terms, and Associated C-Statistics

| Study Outcome | Covariates | Interaction Terms | C-Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health care utilization | |||

| • Preventive visits | • Age | • None | • 0.662 |

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Primary language spoken in the home | |||

| • Current health insurance coverage | |||

| • Outpatient sick visits | • Gender | • None | • 0.605 |

| • Age | |||

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Current health insurance coverage | |||

| • Family structure | |||

| • ED sick visits | • Gender | • Household income*age | • 0.606 |

| • Age | |||

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Current health insurance coverage | |||

| • Family structure | |||

| Child health | |||

| • Parental assessment of global health | • Age | • Household income*age | • 4734368* |

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Primary language spoken in the home | |||

| • Missed days of school | • Gender | • None | • 0.574 |

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Primary language spoken in the home | |||

| • Family structure | |||

| Health-promoting behaviors | |||

| • Frequency of being read to daily | • Gender | • Household income*age | • 2448333* |

| • Age | |||

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Primary language spoken in the home | |||

| • Preventive visits | |||

| • Frequency of obtaining sufficient sleep nightly | • Age | • Household income*race and ethnicity | • 3094272* |

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Primary language spoken in the home | |||

| • Current health insurance | |||

| • Family structure | |||

| • Preventive visits | |||

| • Helmet usage | • Gender | • Household income*age | • 4693080* |

| • Age | |||

| • Race and ethnicity | • Household income*race and ethnicity | ||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | • Household income*family structure | ||

| • Family structure | |||

| • Preventive visits | |||

| • Screen time | • Gender | • Household income*age | • 0.844 |

| • Age | |||

| • Race and ethnicity | • Race and ethnicity*family structure | ||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Family structure | |||

| • Preventive visits | |||

| • History of ever being breastfed | • Age | • Household income*race and ethnicity | • 0.657 |

| • Race and ethnicity | |||

| • Household income | |||

| • Highest attained parental education | |||

| • Primary language spoken in the home | |||

| • Family structure | |||

| • Preventive visits |

Akaike information criterion (AIC)

Footnotes

All authors have met the following criteria: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. American Academy of Pediatrics The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 pt 1):184–186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Pediatric Practice Standards of Child Care. Evanston, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics. History of medical home at the AAP. 2010. Available at: www.medicalhomeinfo.org/about/ Accessed September 30, 2010

- 4.Sia C, Tonniges TF, Osterhus E, Taba S. History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics. 2004;113(suppl 5):1473–1478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homer CJ, Forbes P, Horvitz L, Peterson LE, Wypij D, Heinrich P. Impact of a quality improvement program on care and outcomes for children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(5):464–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lafata JE, Xi H, Divine G. Risk factors for emergency department use among children with asthma using primary care in a managed care environment. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(4):268–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homer CJ, Klatka K, Romm D, et al. A review of the evidence for the medical home for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/4/e922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liptak GS, Burns CM, Davidson PW, McAnarney ER. Effects of providing comprehensive ambulatory services to children with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(10):1003–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooley WC, McAllister JW, Sherrieb K, Kuhlthau K. Improved outcomes associated with medical home implementation in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christakis DA, Mell L, Koepsell TD, Zimmerman FJ, Connell FA. Association of lower continuity of care with greater risk of emergency department use and hospitalization in children. Pediatrics. 2001;107(3):524–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.HR 3590, 111th Leg, Session 2 (Washington, DC, 2010).

- 12.Strickland BB, Jones JR, Ghandour RM, Kogan MD, Newacheck PW. The medical home: health care access and impact for children and youth in the United States. Pediatrics 2011;127(4):604–611 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Frankel MR, Osborn LM, Srinath KP, Giambo P. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children's Health, 2003. Vital Health Stat. 2005;1(43):1–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):38–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brachlow AE, Ness KK, McPheeters ML, Gurney JG. Comparison of indicators for a primary care medical home between children with autism or asthma and other special health care needs: National Survey of Children’s Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(4):399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oswald DP, Bodurtha JN, Willis JH, Moore MB. Underinsurance and key health outcomes for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/2/e341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raphael JL, Guadagnolo BA, Beal AC, Giardino AP. Racial and ethnic disparities in indicators of a primary care medical home for children. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunny KA, Perri M., III Single-item vs multiple-item measures of health-related quality of life. Psychol Rep. 1991;69(1):127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eiser C, Morse R. Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(4):347–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. Bright Futures: Guidelines of Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duursma E, Augustyn M, Zuckerman B. Reading aloud to children: the evidence. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(7):554–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahl RE. The impact of inadequate sleep on children’s daytime cognitive function. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996;3(1):44–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkin PC, Howard AW. Advances in the prevention of children’s injuries: an examination of four common outdoor activities. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(6):719–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall SJ, Biddle SJ, Gorely T, Cameron N, Murdey I. Relationships between media use, body fatness and physical activity in children and youth: a meta-analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(10):1238–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharif I, Sargent JD. Association between television, movie, and video game exposure and school performance. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/4/e1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmerman FJ, Christakis DA. Children’s television viewing and cognitive outcomes: a longitudinal analysis of national data. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(7):619–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Remley DT. Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(4):525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monasta L, Batty GD, Cattaneo A, et al. Early-life determinants of overweight and obesity: a review of systematic reviews. Obes Rev. 2010;11(10):695–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benson V, Marano MA. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey. Vital Health Stat 1998;10:199 [PubMed]

- 30.Allred NJ, Wooten KG, Kong Y. The association of health insurance and continuous primary care in the medical home on vaccination coverage for 19- to 35-month-old children. Pediatrics. 2007;119(suppl 1):S4–S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berman S, Armon C, Todd J. Impact of a decline in Colorado Medicaid managed care enrollment on access and quality of preventive primary care services. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1474–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brousseau DC, Dansereau LM, Linakis JG, Leddy T, Vivier PM. Pediatric emergency department utilization within a statewide Medicaid managed care system. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(4):296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coyle AJ. Effect of Health Determinants on Immunization Rates of Two-Year-Old Children in Denton County [doctoral thesis] Denton, TX: Texas Woman's University; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill JM, Fagan HB, Townsend B, Mainous AG., III Impact of providing a medical home to the uninsured: evaluation of a statewide program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(3):515–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bobo JK, Gale JL, Thapa PB, Wassilak SG. Risk factors for delayed immunization in a random sample of 1163 children from Oregon and Washington. Pediatrics. 1993;91(2):308–314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Irigoyen M, Findley SE, Chen S, et al. Early continuity of care and immunization coverage. Ambul Pediatr. 2004;4(3):199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kempe A, Beaty B, Englund BP, Roark RJ, Hester N, Steiner JF. Quality of care and use of the medical home in a state-funded capitated primary care plan for low-income children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(5):1020–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson CS, Higman SM, Sia C, McFarlane E, Fuddy L, Duggan AK. Medical homes for at-risk children: parental reports of clinician-parent relationships, anticipatory guidance, and behavior changes. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ortega AN, Stewart DC, Dowshen SA, Katz SH. The impact of a pediatric medical home on immunization coverage. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(2):89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenthal J, Rodewald L, McCauley M, et al. Immunization coverage levels among 19- to 35-month-old children in 4 diverse, medically underserved areas of the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/113/4/e296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith PJ, Santoli JM, Chu SY, Ochoa DQ, Rodewald LE. The association between having a medical home and vaccination coverage among children eligible for the vaccines for children program. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):130–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker LC, Baker LS. Excess cost of emergency department visits for nonurgent care. Health Aff (Millwood). 1994;13(5):162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cunningham PJ, Clancy CM, Cohen JW, Wilets M. The use of hospital emergency departments for nonurgent health problems: a national perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 1995;52(4):453–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carret ML, Fassa AC, Domingues MR. Inappropriate use of emergency services: a systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25(1):7–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. 2007. Available at: http://practice.aap.org/content.aspx?aid=2063 Accessed July 10, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA Program to Evaluate Patient-Centered Medical Homes. NCQA News Release 2008. Available at: Available at: www.ncqa.org/tabid/641/Default.aspx Accessed September 30, 2010 [Google Scholar]