Abstract

A critical need still remains for effective delivery of RNA interference (RNAi) therapeutics to target tissues and cells. Self-assembled lipid- and polymer-based systems have been most extensively explored for transfection with small interfering RNA (siRNA) in liver and cancer therapies. Safety and compatibility of materials implemented in delivery systems must be ensured to maximize therapeutic indices. Hydrogel nanoparticles of defined dimensions and compositions, prepared via a particle molding process that is a unique off-shoot of soft lithography known as PRINT (Particle Replication in Non-wetting Templates), were explored in these studies as delivery vectors. Initially, siRNA was encapsulated in particles through electrostatic association and physical entrapment. Dose-dependent gene silencing was elicited by PEGylated hydrogels at low siRNA doses without cytotoxicity. To prevent disassociation of cargo from particles after systemic administration or during post-fabrication processing for surface functionalization, a polymerizable siRNA pro-drug conjugate with a degradable, disulfide linkage was prepared. Triggered release of siRNA from the prodrug hydrogels was observed under a reducing environment while cargo retention and integrity were maintained under physiological conditions. Gene silencing efficiency and cytocompatibility were optimized by screening the amine content of the particles. When appropriate control siRNA cargos were loaded into hydrogels, gene knockdown was only encountered for hydrogels containing releasable, target-specific siRNAs, accompanied by minimal cell death. Further investigation into shape, size, and surface decoration of siRNA-conjugated hydrogels should enable efficacious targeted in vivo RNAi therapies.

Keywords: PRINT, soft lithography, siRNA, hydrogel, nanoparticle, gene silencing

Introduction

Gene silencing via RNA interference (RNAi)1,2 has demonstrated great potential for the treatment of diseases3,4 by halting the production of target proteins. The major challenge in realizing the potential of RNAi therapies resides in delivering small interfering RNA (siRNA) effectively to the cytoplasm of a target cell. With a highly negatively charged backbone and a molecular weight of ca. 13 kDa, siRNA is unable to effectively cross cell membranes without assistance. Additionally, siRNA is susceptible to degradation by ubiquitous RNases in serum. A suitable carrier is required to enhance stability and facilitate delivery to the cytoplasm of cells. Exemplar carriers include oligonucleotide conjugates5-14, polyplexes8,15-18, and lipoplexes19-22. After systemic administration, the siRNA carrier encounters several biological hurdles en route to the target tissue and cell such as clearance by the reticuloendothelium system, protein fouling, and size requirements to reach particular tissues. Designing delivery vehicles with surface decorations including stealthing (e.g. polyethylene glycol, PEG23) and targeting (e.g. peptide13) ligands may promote prolonged circulation and passive delivery to tissues of interest followed by actively targeting cell surface receptors for internalization by desired cells.

Hydrogels and nanogels have been explored as delivery vector candidates for transfection of cells with siRNA. Effective gene knockdown in kidney, epithelial, ovarian, and hepatoma cell lines has been achieved by siRNA-associated hydrogels and nanogels24-28. Due to their robust and tunable mechanical properties, hydrogel micro- or nano-particles may enable delivery of siRNA to a wide range of tissues in vivo including delivery to circulating cells. Bottom-up approaches for encapsulating siRNA in nanogels through electrostatic attraction post-fabrication may result in dynamic association of cargo, uncontrollable cargo release, and modification of particle surface properties. Particle Replication in Non-wetting Templates (PRINT®) technology allows for fabrication of hydrogels with control over size, shape, composition, surface chemistry, and modulus such that delivery properties may be tuned to particular applications29-36. Encapsulation of siRNA in hydrogels may be engineered with PRINT technology, which allows for direct physical entrapment or covalent incorporation of siRNA during particle fabrication.

Results and Discussion

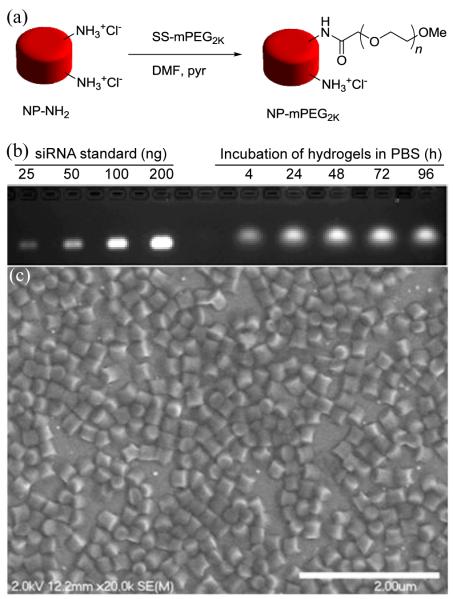

Transfection of cancer cells with siRNA electrostatically entrapped in hydrogels

Initially, a highly cationic, moderately crosslinked hydrogel composition (Table S1) was pursued to allow for physical entrapment and electrostatic association of siRNA within cylindrical (diameter [d] = 200 nm; height [h] = 200 nm) PRINT particles prepared by a film-split technique. To promote cytocompatibility and dispersibility of highly cationic hydrogel nanoparticles in aqueous media, amine handles on hydrogels were reacted with succinimidyl succinate monomethoxy PEG2K (Fig. 1a). After PEGylating the hydrogels, a concomitant decrease in the ζ-potential was observed (Table S2), resulting in a low surface charge that would be minimally toxic to cell membranes. Steady release of siRNA from the hydrogel particles in PBS at 37 °C was observed over time, reaching maximum concentration around 48 h (Fig. 1b). By gel electrophoresis, siRNA loading was determined to be about 1.4 wt%, and encapsulation efficiency of siRNA in hydrogels was determined to be ca. 28% (1.4 wt% final siRNA loading in particles relative to the 5 wt% siRNA charged into the composition of the pre-particle solution). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the hydrogel particles demonstrates their cylindrical shape and dimensions (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

(a) Reaction scheme for PEGylation of hydrogels with succinimidyl succinate monomethoxy PEG2K (SS-mPEG2K), (b) time-dependent release of siRNA from particles incubated at 2 mg/mL and 37 °C in PBS, and (c) Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of particles illustrating their 200×200 nm cylindrical dimensions (scale bar = 2 μm).

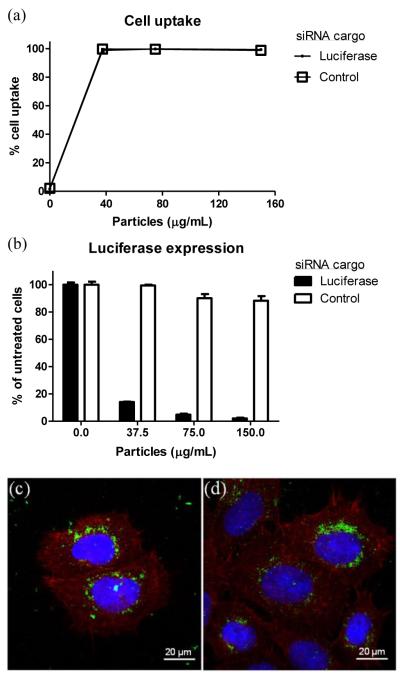

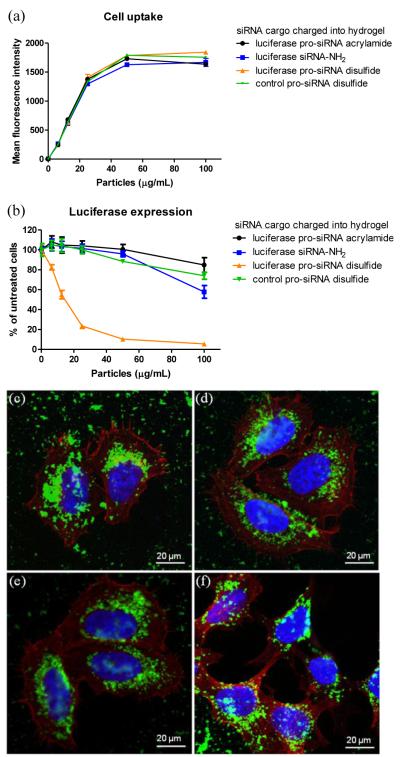

To evaluate the transfection potential of particles loaded with siRNA, a stably-transfected, luciferase-expressing human cervical cancer (HeLa/luc) cell line was utilized for in vitro studies. Particles were dosed on HeLa cells for 4 h followed by 72 h incubation. Due to the positive charge of the particles, the PRINT hydrogel particles were readily internalized into the HeLa cells (Fig. 2a) as determined by flow cytometry. Dose-dependent knockdown of luciferase expression (Fig. 2b) was observed for HeLa cells incubated with the anti-luciferase siRNA-charged particles with a half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of ca. 6 nM siRNA. Conversely, PRINT hydrogel particles charged with a control siRNA sequence did not elicit gene knockdown, implying that transfection was sequence-specific (Fig. 2b). Additionally, both particles were found to be cytocompatible with HeLa cells (Fig. S1). Confocal microscopy of HeLa cells dosed with PEGylated particles (Fig. 2c,d) shows the internalization of fluorescent particles and their distribution throughout the cellular cytoplasm as well as the perinuclear region. Even though the desired cell activity was achieved with these particles, subsequent efforts to modulate in vivo behavior by conjugation of targeting ligands to the particle surface resulted in extensive premature release of siRNA. For example, 50% loss of encapsulated cargo was observed during a sequence of reactions to add targeting moieties to the particle surface (Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

siRNA delivery with PEGylated cationic hydrogels to luciferase-expressing human cervical cancer (HeLa/luc) cells. (a) Cellular uptake. HeLa/luc cells were dosed with particles for 4 h followed by trypan blue treatment and flow cytometry analysis. (b) Luciferase expression. HeLa/luc cells were dosed with particles for 4 h followed by removal of particles and 72 h incubation in media. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. The error bars represent standard deviation from triplicate wells in one experiment. (c) and (d) Confocal micrographs. HeLa/luc cells were dosed with 50 μg/mL particles containing (c) luciferase or (d) control siRNA cargos for 4 h. Cellular actin cytoskeleton was stained with phalloidin (red) and nuclei with DAPI (blue), while particles (green) were labeled with the fluorescent monomer fluorescein O-acrylate during particle fabrication.

siRNA prodrug for triggered release from hydrogels

In order to combat the premature release issues with the PRINT hydrogel particles described above, an alternative prodrug strategy was employed which involved covalently conjugating the siRNA directly to the PRINT hydrogel particles. Acrydite DNA oligonucleotides have been incorporated into hydrogels for nucleic acid hybridization assays37,38 while a CpG oligonucleotide methacrylamide has been copolymerized into aciddegradable microparticles to invoke immune responses39,40. For the triggered release of therapeutic conjugates from particles or delivery vectors under biologically relevant conditions, acidlabile41-43, enzymatically degradable44,45, and redox-sensitive linkages46 have been examined. Glutathione and reducing enzymes are present at high concentrations inside cells relative to the extracellular space in normal and cancer cell lines47. Considering the serum stability of disulfide conjugates46,48, cleavage of disulfide linkages in therapeutic conjugates may selectively occur in the intracellular reducing environment. Disulfide-siRNA conjugates to polymers and lipids have been previously reported6,7,10-12 as reductively-labile systems.

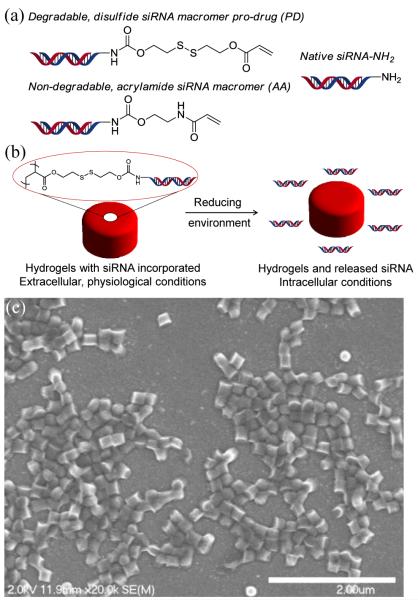

In this work, siRNA was derivatized with a photopolymerizable acrylate bearing a degradable disulfide linkage for reversible covalent incorporation into the PRINT hydrogel nanoparticles (Fig. 3a). In the designed ‘pro-siRNA hydrogels’, it was envisioned that the siRNA cargo would be retained in the particle until entry of the particle into the cytoplasm of a cell, where the disulfide linkage would be cleaved in the reducing environment, allowing for release and delivery of the siRNA (Fig. 3b). A water-based pre-particle composition containing the disulfide siRNA pro-drug and a higher content of hygroscopic, liquid monomers (Table S3) was applied to fabricate cylindrical (d = 200 nm; h = 200 nm) loosely-crosslinked cationic PRINT hydrogel particles using a film-split technique. SEM micrographs confirmed the dimensions and shape of cylindrical siRNAcontaining particles (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

(a) Structures of degradable and non-degradable siRNA macromers as well as native siRNA, (b) Illustration of pro-siRNA hydrogel behavior under physiological and intracellular conditions, and (c) SEM micrograph of pro-siRNA, 200 × 200 nm cylindrical nanoparticles (scale bar = 2 μm).

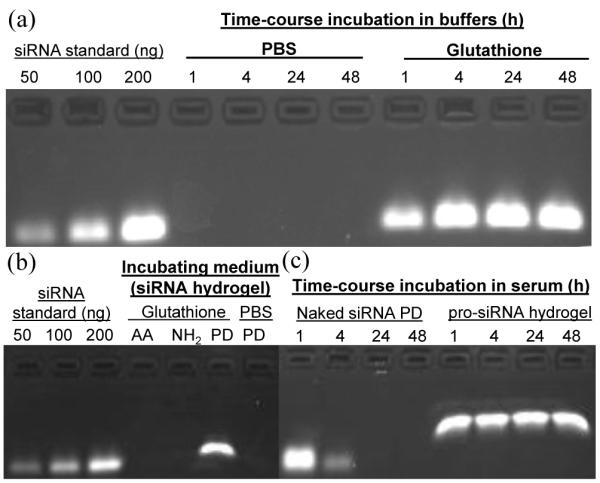

To study the response of pro-siRNA hydrogels to a reducing environment, non-disulfide acrylamide siRNA-based hydrogel particles and native siRNA-complexed particles were prepared as controls (Fig. 3a). Release of native siRNA-NH2 occurred rapidly from these porous, loosely-crosslinked hydrogels (Fig. S4). Fig. S5 showed that different siRNAs were loaded into hydrogel particles and remained associated with particles directly after harvesting. Unconjugated siRNA was found in hydrogels charged with native siRNA or siRNA macromers due to incomplete conversion; therefore, in the following experiments all particles were extensively washed with 10x PBS to remove the sol fraction containing free siRNA. The time-dependent release of the siRNA from the pro-drug PRINT hydrogel particles was evaluated under physiological and reducing conditions (Fig. 4a). The siRNA was retained in the hydrogel particles over 48 h at 37 °C in PBS while the siRNA was quickly released from hydrogels when incubated in a reducing environment (5 mM glutathione), reaching maximum concentration around 4 h (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Release profiles and stability of siRNA in 30% AEM-based hydrogels. All hydrogels were washed with 10x PBS buffer to remove the sol fraction containing unconjugated siRNA before release studies were performed. (a) Time-dependent incubation of pro-siRNA hydrogels (1 mg/mL) in PBS and under reducing conditions (glutathione, 5 mM) at 37 °C. (b) Selective release of the disulfide-coupled siRNA prodrug (PD) from hydrogels under reducing conditions compared to the acrylamide (AA) macromer and native siRNA (NH2). Hydrogels were incubated in 10x PBS with or without 5 mM glutathione for 4 h at 1 mg/mL and 37 °C. (c) Retention of siRNA integrity when conjugated to hydrogels after exposure to 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) over time. Naked siRNA PD macromer was incubated at 36 ug/mL in 10% FBS for given times, proceeded by storage of solution. pro-siRNA hydrogels were incubated at 1.2 mg/mL in 10% FBS at 37 °C for given times followed by incubation in 10x PBS (5 mM glutathione) for 4 h at 1.2 mg/mL and 37 °C to release siRNA. Differences in siRNA migration observed in gels among the standards and samples which were released from hydrogels incubated in PBS and 10x PBS may arise from the differences in salt concentrations of sample solutions.

Moreover, the siRNA conjugate did not even leak out of the hydrogel particles when they were exposed to high salt concentration buffer (10x PBS) at 37 °C for 4 h (Fig. 4b). Incubation of the non-disulfide, non-degradable acrylamide control siRNA hydrogel particles did not result in release of the siRNA under reducing conditions as expected. Stability of the siRNA covalently conjugated to the PRINT hydrogel particles was tested by incubation of the particles in serum (10% FBS) as a function of time. Over 48 h, the siRNA in the pro-drug PRINT hydrogel particles could be protected from degradation by RNases when incubated in serum while siRNA in the form of the simple macromonomer in the absence of the particle to protect it was rapidly degraded in serum under the same conditions (Fig. 4c).

pro-siRNA hydrogels for gene silencing

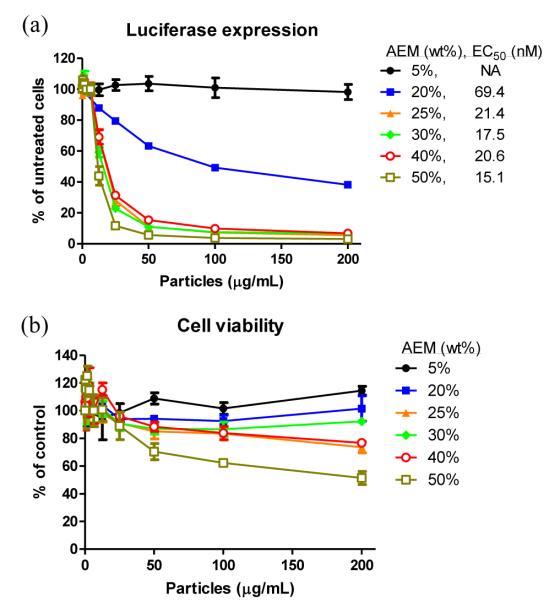

The PRINT particles were designed to have a positive zeta potential to facilitate cell internalization and endosomal escape by including an amine monomer (AEM, 2-aminoethylmethacrylate hydrochloride). It is known that excessive amine content in hydrogels may disrupt and destroy the plasma membrane, eliciting cell death. Conversely, an insufficient amine content may not enable efficient cell uptake and endosomal escape for transfection. To optimize cytocompatibility and gene silencing efficiency of pro-siRNA hydrogels, the AEM content was varied from 5 to 50 wt% (Table S3). Pro-siRNA hydrogels were not PEGylated as were siRNA-complexed hydrogels whereby the cytocompatibility of bare particles would be determined. For systemic delivery of particles in vivo, sheddable coatings that reveal bare particles are attractive to enable targeting and endosomal escape for effective gene delivery49,50.

ζ-potentials of cationic hydrogels increased with amine content and the Z-average diameters (Dz) of the resultant particles ranged from 250 to 350 nm (Table 1). Encapsulation of the siRNA in the hydrogel PRINT particles reached a roughly constant value once the amine content was greater than or equal to 20 wt% (Fig. S6). The encapsulation efficiency was determined to be ca. 35% for AEM contents ≥ 20 wt% while when only using 5% AEM, the encapsulation was lower (ca. 15%). When the pro-drug, disulfide-containing siRNA hydrogel PRINT particles were dosed onto luciferase-transfected HeLa cells (HeLa/luc) for 5 h followed by 48 h incubation at 37 °C, dosedependent knockdown of the luciferase expression was observed (Fig. 5a) for hydrogels with amine contents greater than 5 wt% AEM. Cytocompatibility was maintained at the lower amine contents and dosing concentrations (Fig. 5b). It appeared that the 30% AEM-containing PRINT hydrogel particles provided the ideal combination of gene silencing efficiency (EC50 ~ 20 nM siRNA) and cytocompatibility (even at high dosing concentrations).

Figure 5.

(a) Luciferase expression and (b) viability of HeLa/luc cells dosed with cationic pro-siRNA hydrogels fabricated with different amine (AEM) contents. Cells were dosed with particles for 5 h followed by removal of particles and 48 h incubation in media. Data are representative of two independent experiments. The error bars represent standard deviation from triplicate wells in the same experiment. Half maximal effective concentrations (EC50s) of siRNA (nM) for luciferase gene knockdown are listed in the legend. EC50 was not available (NA) for hydrogels prepared with 5 wt% AEM due to the absence of dose-dependent luciferase knockdown.

To further investigate the in vitro gene knockdown efficacy of the PRINT hydrogel particles, the 30% AEM-based hydrogel composition was utilized with four different cargos: (1) native luc siRNA, (2) degradable disulfide luc siRNA, (3) non-degradable, acrylamide luc siRNA, and (4) degradable disulfide control siRNA. Zetasizer analysis of the hydrogel PRINT particles indicated that their size and charge were similar (Table S4) and gel electrophoresis (Figs. S7) allowed for confirmation of the release of the various cargos. After dosing the particles on cells and incubating for 48 h, cell viability was maintained above 80% for all of the samples across all dosing concentrations, except for the particles charged with the free siRNA (Fig. S8). Uptake of all of the hydrogel particles approached saturation at around 50 μg/mL particle concentration (Fig. 6a). Dose-dependent silencing of luciferase expression was elicited notably for the pro-drug, disulfide-based siRNA-containing hydrogel particles while the control particles did not elicit significant gene knockdown (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

30% AEM-based hydrogel particles charged with different siRNA cargos for transfection of HeLa cells. (a) Cellular uptake. HeLa/luc cells were dosed with particles for 4 h followed by trypan blue treatment and flow cytometry analysis. (b) Luciferase expression. HeLa/luc cells were dosed with particles for 4 h followed by removal of particles and 48 h incubation in media. Data in (a) and (b) represent one of two independent experiments. The error bars represent standard deviation from triplicate wells in the same experiment. Note that all hydrogels were thoroughly washed after fabrication to remove non-conjugated siRNA in the sol fraction. (c)-(f) Confocal micrographs. HeLa/luc cells were dosed with 50 μg/mL hydrogels containing (c) luc PD (d) luc siRNA-NH2, (e) luc acrylamide, and (f) control PD siRNA cargos for 4 h. Cellular actin cytoskeleton was stained with phalloidin (red) and nuclei with DAPI (blue) while particles (green) were labeled with the fluorescent monomer, DyLight 488 maleimide.

The transfection efficiency between siRNA-complexed, PEGylated particles and pro-siRNA hydrogels is comparable, which can be explained by differences in release characteristics. PEGylated particles release siRNA slowly in PBS while pro-siRNA hydrogels rapidly release siRNA under intracellular conditions. Confocal microscopy images of HeLa cells dosed with particles (Figs. 6c-f) illustrates uptake of the particles, which accumulated largely in the cytoplasm and perinuclear region. Particles appear significantly brighter in Figs. 6c-f compared to Figs. 2c,d due to the higher fluorescence intensity emitted by DyLight 488 compared to fluorescein. Given the internalization of cationic particles by HeLa cells and distribution throughout the cytoplasm and perinuclear area, potential exists for the encapsulation of other therapeutic nucleic acids in hydrogel nanoparticles to transfect diseased cells.

Conclusions

siRNA may be physically or electrostatically entrapped within hydrogel nanoparticles to provide effective gene knockdown. Nevertheless, to retain cargo during particle functionalization and under physiological conditions, a covalent incorporation approach was deemed necessary. To our knowledge, this is the first work to polymerize siRNA in hydrogel particles for controlled intracellular delivery. The siRNA cargo was found to be adequately protected by the particles and only released upon reaching the reducing environment of the cytoplasm for effective gene knockdown. Physical dimensions and surface functionalization of pro-siRNA hydrogel nanoparticles with targeting and stealthing ligands are currently under investigation to enable in vivo systemic delivery of siRNAs for the treatment of diseases.

Experimental Section

Materials

2,2′-dithiodiethanol, acryloyl chloride, PEG700 diacrylate, disuccinimidyl carbonate (DSC), 2-aminoethyl methacrylate hydrochloride (AEM), 1-hydroxycyclohexyl phenyl ketone (HCPK), fluorescein O-acrylate, tetraethylene glycol, and Irgacure 2959 were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Poly(vinyl alcohol) 75% hydrolyzed MW ≈ 2 kDa was obtained from Acros Organics. SS-mPEG2K and PEG1K dimethacrylate were from Polysciences, Inc. mPEG5K acrylate and SCM-PEG2K-biotin were from Creative PEGWorks. Anti-human CD71 (Transferrin Receptor) biotinylated OKT9 monoclonal antibody was purchased from eBioscience. UltraAvidin was obtained from Leinco Technologies. Tetraethylene glycol monoacrylate (HP4A) was synthesized in-house and kindly provided by Dr. Matthew C. Parrott, Dr. Ashish Pandya, and Mathew Finniss. PRINT molds were graciously supplied by Liquidia Technologies. siRNAs were purchased as duplexes from Dharmacon, Inc. Sense sequence of amine-modified and native anti-luciferase siRNA: 5′-N6-GAUUAUGUCCGGUUAUGUAUU-3′; anti-sense: 5′- P-UACAUAACCGGACAUAAUCUU-3′. Sense sequence of amine-modified and native control siRNA: 5′-N6- AUGUAUUGGCCUGUAUUAGUU-3′; anti-sense: 5′-P- CUAAUACAGGCCAAUACAUU-3′. All other reagents were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. in molecular biology grade or RNase-free when available.

Synthesis of siRNA macromers

Degradable disulfide macromer precursor: 2,2′-dithiodiethanol (15 mL, 0.12 mol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF (250 mL) in a 500-mL round-bottomed flask containing NEt3 (20.5 mL, 1.2 eq) under a N2 blanket to which acryloyl chloride (11.0 mL, 1.1 eq) was added dropwise and allowed to react for 8 h. Crude product was extracted into dichloromethane against 5% LiCl and purified via silica gel chromatography (EtOAc:hexanes) to provide monoacrylate-substituted 2,2′-dithiodiethanol (63% yield). 2-((2hydroxyethyl)disulfanyl)ethyl acrylate (10 g, 48 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile (100 mL) in a N2-purged 250mL round-bottomed flask, followed by addition of disuccinimidyl carbonate (14.8 g, 1.2 eq). The reaction proceeded for 8 h and product was purified by silica gel chromatography (EtOAc:hexanes 4:1) to afford 2-N-hydroxysuccinimide, 2′acryloyl-dithiodiethanol as a clear, viscous liquid (82% yield). 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 6.46 (dd, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), δ = 6.2 (dd, J = 10.7 Hz, 6.8 Hz, 1H), δ = 5.90 (dd, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), δ = 4.59 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), δ = 4.45 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), δ = 3.05–3.00 (m, J = 6.8 Hz, 4H), δ = 2.87 (s, 4H).

Non-degradable siRNA conjugate precursor: N-hydroxyethyl acrylamide (15 mL, 0.14 mol) was dissolved with DSC (51.9 g, 1.4 eq) in ACN:DMF 4:1 (250 mL) and reacted for 16 h. Afterward, ACN was removed via rotary evaporation and product was extracted into EtOAc against 5% LiCl. Product was concentrated and purified by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc:hexanes 4:1) to provide 2-(succinimidyl carbonate)ethyl acrylamide (80% yield) as a fine white solid. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 6.50 (br, 1H, NH), δ = 6.34 (dd, J = 17.1 Hz, 1H), δ = 6.19 (dd, J = 10.3 Hz, 6.4 Hz, 1H), δ = 5.71 (dd, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), δ = 4.46 (t, J = 5.0, 2H), δ = 3.71 (m, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), δ = 2.87 (s, 4H).

siRNA macromers: siRNA-NH2 (2 mg, 148 nmol, anti-luciferase siRNA or control sequence) was dissolved in DEPC-treated PBS (200 μL) in a 1.5-mL RNase-free Eppendorf tube. Separately, 2N-hydroxysuccinimide, 2′-acryloyl-dithiodiethanol (5.2 mg, 100 eq) or 2-(succinimidyl carbonate)ethyl acrylamide (3.8 mg, 100 eq) was dissolved in RNase-free DMF (150 μL) and added to the solution of siRNA. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 36 h where additional 100 eq of the acrylate or acrylamide were added to the reaction mixture every 12 h. 5 M NH4OAc (50 μL) and EtOH (1.1 mL) were added to the reaction mixture, which was vortexed for 15 s. The sample was incubated in a -80 °C freezer for 4 h followed by centrifugation (14 krpm, 4 °C, 20 min) to pellet the siRNA. The supernatant was decanted and the pellet was washed twice with 70% EtOH (ice-cold) to provide siRNA prodrug (79% yield). HR-ESI-MS: m/z found for siRNA sense strand [M-H]− = 6832.366; m/z calc. for disulfide macromer [M-H]− = 7067.676; found [M-H]− = 7067.855; m/z calc. for siRNA acrylamide macromer [M-H]− = 6974.506; found [M-H]− = 6974.871. Characterization of siRNA prodrug precursors was carried out on a 600 MHz Bruker NMR Spectrometer equipped with a Cryoprobe and siRNA macromonomers were analyzed by an IonSpec Fourier Transform Mass Spectrometer FTMS (20503 Crescent Bay Drive, Lake Forest, CA 92630) with a nano electrospray ionization source in combination with a NanoMate (Advion 19 Brown Road, Ithaca, NY 14850) chip based electrospray sample introduction system and nozzle operated in the negative ion mode as well as reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Figs. S9).

Fabrication of hydrogels via PRINT process

Pre-particle solutions were prepared with listed compositions at 2.5 wt% in RNase-free DMF (for physically entrapped siRNA) or DEPC-treated water containing 0.01 % sodium dodecyl sulfate (for prodrug siRNA, where all remaining steps were conducted in a humidity room maintained at 70% relative humidity). Specifically, for each composition, solid and liquid monomers were dissolved in respective pre-particle solution solvent at a total weight percent of 2.5%. The film-split technique for preparing particles was performed as described in the following: using a #5 wire wound rod (R.D.S.), 150 μL of pre-particle solution was cast at 6 ft/min on a sheet of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET), followed by brief evaporation of solvent with heat gun to yield a transparent film (delivery sheet). 200 × 200 nm cylindrical Fluorocur-patterned PRINT molds (Liquidia Technologies) were laminated against the delivery sheet with moderate pressure (40 psi) and then gently delaminated. The filled mold was laminated against corona-treated PET and subsequently cured in a UV chamber (λmax = 365 nm, 90 mW/cm2) for 5 min. After photocuring, the mold was removed to reveal an array of particles on PET. Particles were harvested off PET with water mechanically using a cell scraper (1 mL/48 in2). Particles were washed via centrifugation (15 min, 14 krpm, 4 °C), removal of supernatant, and re-suspension in water. Particle yield was determined by thermogravimetric analysis (Q5000IR, TA instruments). Pro-siRNA hydrogels were washed repeatedly with 10x PBS containing 0.05% PVA 2 kDa to remove the sol fraction.

Hydrogels with electrostatically-entrapped siRNA were PEGylated by reacting particles with SS-mPEG2K (2 wt eq, weight equivalents relative to particle mass) using pyridine (2 wt eq) in DMF at 2 mg/mL particle concentration for 6 h at room temperature followed by washing particles with water. For post-functionalization of particles with ligands, SCM-PEG2K-biotin (2 wt eq) was reacted with particles in DMF at 2 mg/mL for 2 h along with pyridine (4 wt eq). NHS-mPEG12 (2 wt eq) was added to quench non-biotinylated amines with pyridine (4 wt eq) in DMF at 2 mg/mL for 30 min. Particles were centrifuged, isolated through removal of supernatant, and washed with PBS. UltraAvidin (0.25 wt eq) was conjugated to biotinylated particles in PBS at 2 mg/mL for 20 min, followed by centrifugation, washing with PBS, and adding biotinylated OKT9 antibody (20 wt meq) for another 20 min at 2 mg/mL, after which particles were washed with PBS to remove unconjugated antibody and re-suspended in PBS at 2 mg/mL.

Particle characterization

Scanning electron microscropy (SEM) enabled imaging of hydrogels that were dispersed on a glass slide and coated with 2 nm of Au/Pd (Hitachi S-4700). ζ-potential measurements were conducted on 20 μg/mL particle dispersions in 1 mM KCl using a Zetasizer Nano ZS Particle Analyzer (Malvern Instruments Inc.).

Analysis of siRNA by gel electrophoresis

2.5% agarose gel in TBE buffer was prepared with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. For studying release of siRNA from hydrogels, aliquots of particle dispersions were centrifuged (15 min, 14 krpm, 4 °C) for recovery of the supernatant at various time points and frozen. Similarly, aliquots of siRNA prodrug incubated in 10% FBS at 37 °C were taken at various time points and frozen for storage. 12 μL of sample (supernatants from particle dispersions, siRNA solutions, or particle dispersions) was mixed with 3 μL of 6x loading buffer (60% glycerol, 0.12 M EDTA in DEPC-treated water) and loaded into the gel. 70 V/cm was applied for 25 min and the gel was then imaged with ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE). Analysis of siRNA band intensity was conducted with Image J software for quantification. siRNA loading was calculated by comparing the maximum amount of siRNA released to the particle mass. Encapsulation efficiency of siRNA was calculated by comparing wt% of final siRNA loading to the siRNA charged into the pre-particle composition (5 wt% of particle).

Cell culture

Luciferase-expressing HeLa cell line (HeLa/luc) was from Xenogen. HeLa/luc cells were maintained in DMEM high glucose supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 units/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and non-essential amino acids. All media and supplements were from GIBCO except for FBS which was from Mediatech, Inc.

In vitro cell uptake analysis

HeLa/luc cells were plated in 96-well plates at 10,000/well and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were dosed with fluorescently-tagged particles in OPTI-MEM at 37 °C (5 % CO2) for 4 h or indicated time for cell uptake studies. Fluorescently-tagged particles were prepared by incorporation of fluorescent monomers (fluorescein O-acrylate for PEGylated particles and DyLight 488 maleimide for pro-siRNA particles) in the particle composition and copolymerization of these monomers into particles matrix. After incubation, cells were washed and detached by trypsinization. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in a 0.4 % trypan blue (TB) solution in Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffers Saline solution (DPBS) to quench the fluorescein fluorescence from particles associated to the cell surface. Cells were then washed and resuspended in DPBS or fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde/DPBS, and analyzed by CyAn ADP flowcytometer (Dako). Cell uptake was represented as percentage of cells that were positive in fluorescein fluorescence.

In vitro cytotoxicity and luciferase expression assays

HeLa/luc cells were plated in 96-well plate at 10,000/well and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were dosed with particles or Lipofec-tamine 2000/siRNA mix in OPTI-MEM at 37 °C (5 % CO2) for 4 or 5 h, then particles were removed, and complete grow medium was added for another 48 h incubation at 37°C. Cell viability was evaluated with Promega CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, and luciferase expression level was evaluated with Promega Bright-Glo™ Luciferase Assay according to manufacturer’s instructions. Light absorption or bioluminescence was measured by a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices). The viability or luciferase expression of the cells exposed to PRINT particles was expressed as a percentage of that of cells grown in the absence of particles. Half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of siRNA required to elicit gene knockdown was determined by applying the dose-dependent gene knockdown data to a log(inhibitor) vs. response variable slope non-linear function in GraphPad Prism software for given siRNA concentrations (calculated from particle concentration and siRNA loading).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

HeLa/luc cells were plated in 8-well chamber slides (BD) at 10,000/well and incubated overnight at 37°C. Cells were dosed with green fluorescent particles (fluorescein or DyLight 488 labeled) in OPTI-MEM at 37 °C (5 % CO2) for 4 h. Cells were then washed three times with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and permeabilized with 0.5% saponin for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were stained with 100 nM phalloidin-AlexaFluor 555 for actin for 1 h at room temperature, and then counterstained with 30 μM DAPI for 15 min. Images were collected with LSM710 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Zetasizer analysis of pro-siRNA hydrogels with variable amine content.

| Amine content (wt%) | ζ-potential (mV) | Dz (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| 5% AEM | +18.2 ± 0.5 | 350.2 ± 5.4 |

| 20% AEM | +22.6 ± 0.1 | 281.6 ± 1.9 |

| 25% AEM | +27.1 ± 0.3 | 307.4 ± 6.6 |

| 30% AEM | +27.9 ± 1.5 | 324.3 ± 5.6 |

| 40% AEM | +30.6 ± 1.0 | 281.3 ± 6.0 |

| 50% AEM | +34.1 ± 0.4 | 253.7 ± 3.4 |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Carolina Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence (NIH-U54-CA119343 and NIH-U54CA151652), National Institutes of Health Director’s Pioneer Award (1DP1OD006432) and R01 (R01EB009565), University of North Carolina Cancer Research Fund, the Chancellor’s Eminent Professorship of Chemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a sponsored research agreement with Liquidia Technologies. We thank Dr. J. Christopher Luft, Dr. Warefta Hasan, Jing Xu, and Luke Roode for helpful discussions throughout this work as well as Dr. Kevin P. Herlihy for particle illustrations in Figures 1 and 2.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT Supporting Information. Compositions of PRINT particles and additional Zetasizer measurements in Tables S1-S4. Viability of HeLa cells dosed with PEGylated hydrogels and pro-siRNA hydrogels containing different siRNA cargos, transfection of HeLa cells with different siRNAs using Lipofectamine, gel electrophoresis of siRNA loaded into and released from different hydrogels, and analysis of siRNAs by HPLC in Figures S1-S9. Completed author list for abbreviated references. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes The authors declare competing financial interest. Joseph DeSimone is a founder, member of the board of directors, and maintains a financial interest in Liquidia Technologies. Liquidia was founded in 2004 to commercialize PRINT technology and other discoveries of Professor Joseph DeSimone and colleagues at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

REFERENCES

- (1).Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Elbashir SM, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Genes Dev. 2001;15:188–200. doi: 10.1101/gad.862301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Leuschner F, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Itaka K, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1624–1625. doi: 10.1021/ja044941d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Musacchio T, Vaze O, D’Souza G, Torchilin VP. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:1530–1536. doi: 10.1021/bc100199c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kim SH, Jeong JH, Lee SH, Kim SW, Park TG. J. Controlled Release. 2006;116:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lee M-Y, Park S-J, Park K, Kim KS, Lee H, Hahn SK. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6138–6147. doi: 10.1021/nn2017793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cutler JI, Zhang K, Zheng D, Auyeung E, Prigodich AE, Mirkin CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9254–9257. doi: 10.1021/ja203375n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).York AW, Huang F, McCormick CL. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:505–514. doi: 10.1021/bm901249n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rozema DB, Lewis DL, Wakefield DH, Wong SC, Klein JJ, Roesch PL, Bertin SL, Reppen TW, Chu Q, Blokhin AV, Hagstrom JE, Wolff JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:12982–12987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Vázquez-Dorbatt V, Tolstyka ZP, Chang C-W, Maynard HD. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2207–2212. doi: 10.1021/bm900395h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nakagawa O, Ming X, Huang L, Juliano RL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8848–8849. doi: 10.1021/ja102635c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Jeong JH, Mok H, Oh Y-K, Park TG. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:5–14. doi: 10.1021/bc800278e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Allen MH, Green MD, Getaneh HK, Miller KM, Long TE. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:2243–2250. doi: 10.1021/bm2003303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Layman JM, Ramirez SM, Green MD, Long TE. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1244–1252. doi: 10.1021/bm9000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Heidel JD, Yu Z, Liu JY-C, Rele SM, Liang Y, Zeidan RK, Kornbrust DJ, Davis ME. P Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:5715–5721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701458104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Convertine AJ, Benoit DSW, Duvall CL, Hoffman AS, Stayton PS. J. Controlled Release. 2009;133:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Akinc A, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:561–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Love KT, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:1864–1869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910603106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Semple SC, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:172–176. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Li S-D, Huang L. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2006;3:579–588. doi: 10.1021/mp060039w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:235–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Krebs MD, Jeon O, Alsberg E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9204–9206. doi: 10.1021/ja9037615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Raemdonck K, Van Thienen TG, Vandenbroucke RE, Sanders NN, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008;18:993–1001. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hu Y, Atukorale PU, Lu JJ, Moon JJ, Um SH, Cho EC, Wang Y, Chen J, Irvine DJ. Biomacromolecules. 2012;10:756–765. doi: 10.1021/bm801199z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Naeye B, Raemdonck K, Remaut K, Sproat B, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;40:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Blackburn WH, Dickerson EB, Smith MH, McDonald JF, Lyon LA. Bioconjate Chem. 2009;20:960–968. doi: 10.1021/bc800547c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Rolland JP, Maynor BW, Euliss LE, Exner AE, Denison GM, DeSimone JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10096–10100. doi: 10.1021/ja051977c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Petros RA, Ropp PA, DeSimone JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5008–5009. doi: 10.1021/ja801436j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Canelas DA, Herlihy KP, DeSimone JM. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2009;1:391–404. doi: 10.1002/wnan.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Parrott MC, Luft JC, Byrne JD, Fain JH, Napier ME, DeSimone JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17928–17932. doi: 10.1021/ja108568g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gratton SEA, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC, Madden VJ, Napier ME, DeSimone JM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:11613–11618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801763105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Wang J, Tian S, Petros RA, Napier ME, Desimone JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11306–11313. doi: 10.1021/ja1043177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Enlow EM, Luft JC, Napier ME, DeSimone JM. Nano Lett. 2011;11:808–813. doi: 10.1021/nl104117p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Merkel TJ, Jones SW, Herlihy KP, Kersey FR, Shields AR, Napier ME, Luft JC, Wu H, Zamboni WC, Wang AZ, Bear JE, DeSimone JM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:586–591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010013108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Pregibon DC, Doyle PS. Anal. Chem. 2008;81:4873–4881. doi: 10.1021/ac9005292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lewis CL, Choi C-H, Lin Y, Lee C-S, Yi H. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:5851–5858. doi: 10.1021/ac101032r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Standley SM, Mende I, Goh SL, Kwon YJ, Beaudette TT, Engleman EG, Fréchet JMJ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:77–83. doi: 10.1021/bc060165i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Beaudette TT, Bachelder EM, Cohen JA, Obermeyer AC, Broaders KE, Fréchet JMJ. Mol. Pharm. 2009;6:1160–1169. doi: 10.1021/mp900038e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Gillies ER, Goodwin AP, Fréchet JMJ. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:1254–1263. doi: 10.1021/bc049853x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).MacKay JA, Chen M, McDaniel JR, Liu W, Simnick AJ, Chilkoti A. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:993–999. doi: 10.1038/nmat2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Oishi M, Sasaki S, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1426–1432. doi: 10.1021/bm034164u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Chau Y, Tan FE, Langer R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:931–941. doi: 10.1021/bc0499174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Satchi-Fainaro R, Puder M, Davies JW, Tran HT, Sampson DA, Greene AK, Corfas G, Folkman J. Nat. Med. 2004;10:255–261. doi: 10.1038/nm1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Meng F, Hennick WE, Zhong Z. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2180–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2001;30:1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Feener EP, Shen WC, Ryser H. J. Clin. Invest. 1986;77:977–984. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Romberg B, Hennink WE, Storm G. Pharm. Res. 2008;25:55–71. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Harris TJ, Green JJ, Fung PW, Langer R, Anderson DG, Bhatia SN. Biomaterials. 2010;31:998–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.