Abstract

Idiopathic primary hyperaldosteronism (IHA) and low-renin essential hypertension (LREH) are common forms of hypertension, characterized by an elevated aldosterone-renin ratio (ARR) and hypersensitivity to Angiotensin II (Ang II). They are suggested to be two states within a disease spectrum that progresses from LREH to IHA as the control of aldosterone production by the renin-angiotensin system is weakened. The mechanism(s) that drive this progression remain unknown. Deletion of Twik-related-acid-sensitive K+ channels (TASK) subunits, TASK-1 and TASK-3, in mice (T1T3KO) produces a model of human IHA. Here, we determine the effect of deleting only TASK-3 on the control of aldosterone production and blood pressure. We find that T3KO mice recapitulate key characteristics of human LREH: salt-sensitive hypertension, mild overproduction of aldosterone, decreased plasma renin concentration with elevated ARR, hypersensitivity to endogenous and exogenous Ang II, and failure to suppress aldosterone production with dietary sodium loading. The relative differences in levels of aldosterone output and ARR, and in autonomy of aldosterone production between T1T3KO and T3KO mice are reminiscent of differences in human hypertensive patients with LREH and IHA. Our studies establish a model of LREH and suggest that loss of TASK channel activity may be one mechanism that advances the syndrome of low renin hypertension.

Keywords: TASK channels, aldosterone, hyperaldosteronism, low renin essential hypertension

Aldosterone plays an important role in the regulation of blood pressure (BP). When overtly dysregulated it causes primary aldosteronism (PA), a syndrome characterized by hypertension, high plasma aldosterone concentration, decreased plasma renin activity, and varying degrees of hypokalemia, and metabolic alkalosis. In PA, aldosterone overproduction is relatively independent of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and, thus, not suppressed by sodium loading. PA is the result of both known (aldosterone-producing adenomas, glucocorticoid-remediable hyperaldosteronism) and unknown causes (idiopathic hyperaldostronism (IHA) with bilateral adrenal hyperplasia.1 A closely related form of hypertension, low renin essential hypertension (LREH), is a more subtle form of aldosterone dysregulation in which plasma aldosterone concentrations may be normal or near normal but are inappropriately high for the level of plasma renin. LREH accounts for a notable 25–30% of patients with essential hypertension.2,3 Using the aldosterone-renin ratio (ARR) as an indicator of the pathophysiology of hypertension,4,5 it has been suggested that LREH and IHA may not be separate disease processes, but rather stages of a disease continuum that progresses from normotension to LREH to IHA as the control of aldosterone production weakens and production becomes relatively autonomous.6–8 Indeed, among normotensive individuals, a high-normal plasma aldosterone concentration and ARR is predictive of future progression to hypertension.9,10 The mechanisms that drive this progression remain ill-defined.8

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of K+ channel activity in the control of aldosterone production.11 Sustained production of aldosterone from adrenal zona glomerulosa cells (ZG) requires extracellular Ca2+ entry via voltage-gated Ca2+ channels that are activated by membrane depolarization.12,13 By their hyperpolarizing activities, K+ channels restrain the production of aldosterone. Indeed, mutations in the human KCNJ5 gene that reduce ion selectivity and impair the ability of the inwardly rectifying K+ channel to maintain negative membrane voltages provide a molecular basis for the excessive overproduction of aldosterone in a subset of patients with tumorigenic PA.11 Mouse have also supported the importance of K channel activity in the control of aldosterone production.14–16 For example, deletion of two mouse genes that encode two-pore domain TASK channel subunits yields hyperaldosteronism. Ablation of Kcnk3 (TASK-1) causes an adrenal zonation defect and a novel form of glucocorticoid-remediable hyperaldosteronism,16 whereas deletion of both KcnK3 and Kcnk9 (TASK-3) produces a syndrome that closely resembles human IHA:15 hypertension, increased urinary excretion of aldosterone, decreased levels of plasma renin, exaggerated ARR, failure to suppress aldosterone production with Na+ loading or to normalize production with angiotensin ll (Ang ll) AT1-receptor (AT1R) blockade. Both TASK-1 and TASK-3 subunits are prominently expressed in adrenal ZG cells.15,17 By forming homo- or hetero-dimeric “leak” K+ channels,18 these subunits provide a background hyperpolarizing conductance that contributes to setting the negative membrane potential of ZG cells.12,17,19 ZG cells lacking both TASK-1 and TASK-3 are depolarized (by~20 mV) which permits autonomous overproduction of aldosterone characteristic of the IHA phenotype.15 Here, we show that deletion of only TASK-3 recapitulates key features of the milder LREH syndrome:8,20–23 salt-sensitive hypertension, mild overproduction of aldosterone, decreased levels of plasma renin, greater sensitivity to Ang II, and maintained resistance to Na+ suppression. We conclude that the progressive loss of TASK channel activity maybe a mechanism that advances the syndrome of low-renin hypertension.

METHODS

Mice

TASK KO mice were generated as previously described24 (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org). Male mice were employed to remove the potential confounds of hormonal surges associated with the estrus cycle. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee.

Metabolic Cage Experiments

Salt Diets

Metabolic cage experiments and blood analysis were conducted as previously described15,25 using one of four experimental protocols (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org, Figure S1 and expanded methods for details). Diets contained either: normal Na+ (NS: 0.3% Na+, 0.8%K+), low Na+ (LS: 0.05% Na+, 0.8%K+), high Na+ (HS, 4.0% Na+, 0.8%K+), or high K+ (HK+: 4.0% K+, 0.3% Na+).

Ang II Delivery

Following NS urine collection (day 4–7) ALZET osmotic minipumps (DURECT Corporation, Cupertino CA) containing Ang II (.040/0.4/0.8/1.2/or 4.0 μg Ang II/kg/min) or 0.9% saline vehicle were implanted subcutaneously. Mice were allowed 1 day of surgical recovery before collection of 24 hr. urine samples (day 10–13) (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Telemetric BP

BP was recorded from conscious, freely behaving mice. Pressure transmitters (Data Sciences International telemetry system; DSI, St. Paul MN) were threaded through the left carotid artery and implanted in the aortic arch (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org). Following 7 days of surgical recovery, BP and heart rate (HR) were recorded (NS, day 8–11) before challenge with HS (day 12–18), or with candesartan (10 mg/kg/day) delivered in the drinking water (day 12–15).

ZG Isolation, RT-PCR, and Western Blot Analysis

The ZG layer was isolated from mouse adrenal glands using laser capture microdissection (AS/LMD, Leica Microsystems, Inc). RNA was isolated for qRT-PCR analysis of TASK-1, Kcnj5, AT1AR, AT1BR, and Cyp11β2 expression. For western blot analysis of CYP11β2 protein, adrenal lysates from a single mouse (2 adrenals) were combined, equivalent total protein diluted with SDS sample buffer, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot using anti-Cyp11β2 antibody (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Electrophysiology

Thinly sectioned adrenal slices (80 μm) were prepared from 35–55 day old mice and ZG cells were identified by their location in subcapsular cell rosettes15. Electrophysiological recordings were obtained at room temperature using patch electrodes (3–5MΩ), an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pCLAMP 10.3 (Molecular Devices). Baseline membrane voltages were recorded in current clamp from ZG cells following 2–4 minutes of perfusion with standard external solution (please see http://hyper.ahajournals.org).

Data Analysis

For each experimental protocol, T1T3KO or T3KO mice were run in parallel with wild-type (WT) mice to control for potential environmental differences among cohorts. Individual animals were run on only one experimental protocol and data were collapsed by genotype across cohorts. Mean Urine aldosterone/creatinine and plasma renin concentration (PRC) were log transformed due to unequal variances and analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. Plasma K+ and Cyp11β2 were compared using a two-way ANOVA. BP and HR were analyzed using a one-way (NS) or repeated measures two-way ANOVA (before and after candesartan, HS). If the overall ANOVA reported a statistical significance (P<0.05), group means were compared using a Bonferroni post hoc test and significance determined if P < 0.05. Dose-response curves for Ang II sensitivity were generated and analyzed with Origin Pro software. An independent t-test compared TASK-1, and Kcnj5 mRNA expression and membrane potential, with significance if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

T3KO mice display mild hyperaldosteronism

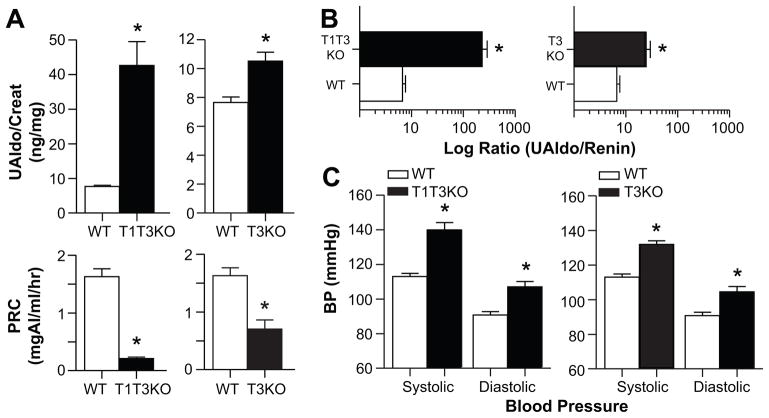

In previous work, we found that TASK-1−/−:TASK-3−/− double knockout mice on a mixed genetic background (SV129/C57BL/6) produced more aldosterone than age-matched control littermates despite lower levels of plasma renin.15 Here, we measured urinary aldosterone excretion (24-h, normalized to creatinine) and PRC in TASK-1−/−:TASK-3−/− mice on a congenic C57BL/6 background (T1T3KO) to determine if the reported phenotypic difference between genotypes was attributable to deletion of the TASK genetic locii. Consistent with our previous observations, T1T3KO mice on a NS-diet displayed overt hyperaldosteronism, producing greater than 4-fold more aldosterone than C57BL/6 WT mice (P<0.001) despite plasma renin levels that were only 20% of that of WT mice (P<0.001; Figure 1A, left). This dysregulation resulted in an ARR that was 30-fold greater than WT, consistent with the previously characterized mouse IHA phenotype (Figure 1B, left). Thus, the PA phenotype is associated with the deletion of TASK-1 and TASK-3 and is not dependent on a particular genetic background.

Figure 1.

Effect of TASK-3 deletion on urinary aldosterone, plasma renin concentration (PRC), and blood pressure in congenic mice. A, upper, 24-hr. urinary aldosterone excretion normalized to creatinine (ng/mg, UAldo/creatinine) in T1T3KO (black bars, left; n=12), T3KO (black bars, right; n=31) and WT mice (white bars, n=38) on NS diet (0.32% Na+, 0.8% K+; 7 days on diet). A, lower, PRC (mg Ang I/ml/hr) of same WT and KO mice. B, Ratio of UAldo to PRC calculated per mouse and averaged per genotype. C, 24-hr. SBPs and DBPs of conscious mice: T1T3KO (n=5), T3KO (n=11), WT (n=11) using radio-telemetry. Values represent mean ± SEM; *comparison to WT mice (P<0.05).

The expression of both TASK-1 and TASK-3 subunits in ZG cells allows the potential for homo- and hetero-dimeric TASK channel conformations.18 To determine whether TASK-3 deletion is sufficient to recapitulate the IHA phenotype of double knockout mice, we studied congenic T3KO mice in parallel. Urinary aldosterone excretion in T3KO mice was elevated modestly but significantly (37%, P=0.017) above that of WT mice (Figure 1A, upper right) and was accompanied by reduced levels (P<0.001) of plasma renin (Figure 1A, lower right). These opposing changes in aldosterone output and renin status in T3KO mice produced an elevated ARR that was 2.6-fold greater than that of WT mice but was nonetheless an order of magnitude less than that of T1T3KO mice (Figure 1B, right). These comparative differences in the level of aldosterone output and ARR are reminiscent of observations in human hypertensive patients with LREH and IHA.5,8 To determine if these mice were hypertensive, we placed pressure transmitters in the aortic arch to determine BP in conscious freely behaving mice by telemetry. We found that both T1T3KO and T3KO mice have significantly higher 24-hr ambulatory systolic (SBP, P<0.001) and diastolic (DBP, P<0.01) BPs than WT (Figure 1C). Thus, we conclude that both T1T3KO and T3KO mice are hypertensive, the former due to IHA and the latter to low renin primary hypertension.

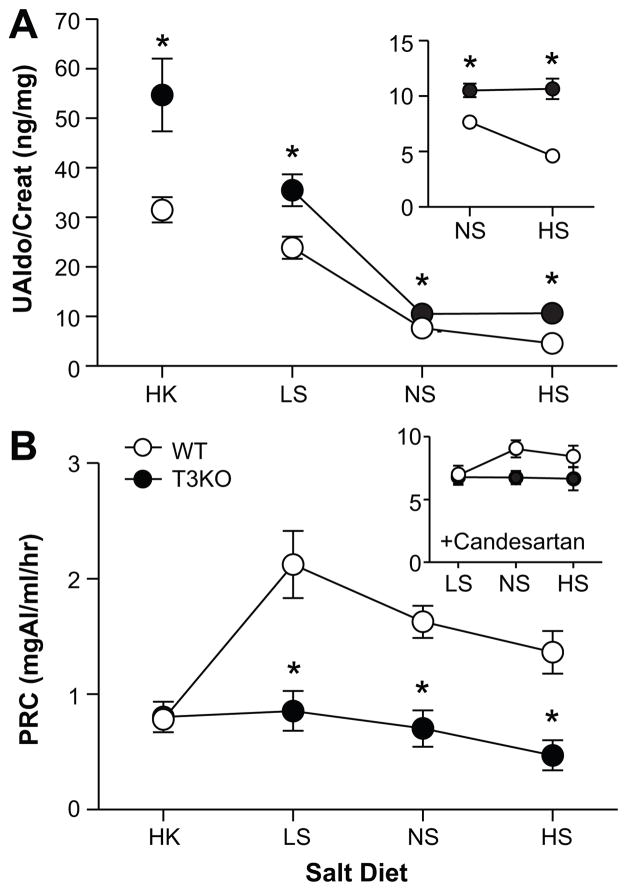

T3KO mice display hyperaldosteronism that is resistant to salt suppression

Ang II and extracellular K+ are the two major regulators of aldosterone production in vivo.15,22,26,27 Consistent with the stimulation of the RAS, limiting dietary Na+ (LS) increased urinary aldosterone excretion above that produced on a NS diet in both WT and T3KO mice (P=0.011). Nevertheless, urinary aldosterone excretion in T3KO mice remained 1.6-fold that of WT (Figure 2A). T3KO mice also displayed an augmented response to dietary K+ feeding (HK) that was 1.7-fold that of WT. However, the dysregulation of aldosterone production in T3KO mice was most striking in mice fed a HS diet, when the activity of RAS is decreased. Unlike WT, T3KO mice failed to suppress aldosterone output with HS but maintained excretion at NS feeding levels. This resistance to HS inhibition was shared by T1T3KO mice (data not shown). Thus, HS challenge revealed a component of aldosterone output in T3KO mice that is independent of the RAS.

Figure 2.

Effect of diet on UAldo and PRC. A, 24-hr. UAldo/creatinine (ng/mg) of WT (white circles) and T3KO mice (black circles) on each of four salt diets: HK (n=11 per group), LS (n=20-25), NS (n=31-38), HS (n=25-32). A, inset, Expanded scale to show increase in UAldo/creatinine in T3KO versus WT mice on NS or HS diet. B, PRC (mg AngI/ml/hr) of WT and T3KO mice on salt diets. B, inset PRC after candesartan treatment (10mg/kg/day) on LS, NS, or HS for WT and T3KO mice (LS: n=20-25; NS: n=11; HS: n=11). Values represent mean ± SEM; *comparison to WT mice (P<0.05).

T3KO mice maintained a low renin status on all Na+ diets compared to WT (P<0.002; Figure 2B)). However, HK feeding reduced renin concentration levels of WT mice to that of T3KO implying a direct role for TASK-3 in the regulation of renin secretion. Nevertheless, treatment with candesartan, an insurmountable AT1R receptor blocker, that removes Ang II AT1R-activated feedback inhibition of renin secretion, restored plasma levels of renin in T3KO mice to values that were indistinguishable from those of WT (P=0.63, Figure 2C). Thus, we conclude that the low renin status of T3KO mice on all Na+ diets is not likely the result of reduced renin stores or impaired vesicular secretion but rather an enhanced sensitivity of JG cells to Ang II inhibition, a consequence of TASK-3 subunit deletion.

Conventional determinants of autonomous aldosterone production are not changed in T3KO mice

The deletion of both TASK-1 and TASK-3 results in a ~20 mV membrane depolarization of ZG cells and provides a cellular explanation for the overt autonomous overproduction of aldosterone in the T1T3KO mouse strain.15 By using current clamp recordings, we found that baseline membrane potential in ZG cells from T3K0 mice was not different from WT (P=0.868), remaining at the hyperpolarized level characteristic of these cells (Figure 3A). Moreover, T3KO mice displayed a mild but significant hypokalemia (P<0.001, Figure 3B) that would be predicted to further hyperpolarize the ZG cell in vivo. Neither the mRNA expression of TASK-1 subunits (P=0.505, Figure 3C) nor that of the Kcnj5 inwardly-rectifying K+ channel (P=0.240, Figure 3D) was upregulated to compensate for the loss of the TASK-3 expression. Therefore, we conclude that a difference in baseline ZG membrane potential cannot account for the mild overproduction of aldosterone observed in T3KO mice.

Figure 3.

Membrane potential, K+ channels and Cyp11β2 expression in the adrenal ZG. T3KO hyperaldosteronism is not explained by differences in ZG baseline Vm, plasma K+, or TASK-1 expression. A, Baseline Vm (mV) of ZG cells in adrenal slices from WT (white bars, n=16) and T3KO mice (black bars, n=17) determined in current clamp. B, Plasma K+ (mmol/L) in WT (white circles) and T3KO mice (black circles) on salt diets (HK: n=11, NS, LS, HS: n=21-26). *Indicates main effect of genotype (P<0.001). C, D, Expression of mRNA (C,TASK-1, TASK-3) and (D, Kcnj5,) in ZG layer isolated by laser microdissection, from WT (n=6) and T3KO (n=6) adrenal slices, measured by RT-PCR and expressed as fold-initial mRNA (2−dCt) relative to actin mRNA. E, mRNA expression of Cyp11β2 in ZG layer, NS (n=6, *P<0.001) or HS (n=4, *P=0.038). F, Western blot analysis of lysates (20 ug total protein) prepared from mouse adrenals (2 adrenals/lane): NS(n=3); HS(n=5); LS(n=4), detected with anti-aldosterone synthase (Cyp11β2) antibody. Values represent mean ± SEM, *comparison to WT mice (P<0.05).

Aldosterone synthase (Cyp11β2) expression is restricted to the ZG of the adrenal gland28 and is the terminal cytochrome P450 enzyme catalyzing the three step conversion of 11-deoxycorticosterone to aldosterone. The mRNA for Cyp11β2 is present at low levels in normal adrenals and is increased in aldosterone secreting tumors.29 We found that the level of the transcript for Cyp11β2 was increased in T3KO mice fed a NS or HS diet (P<0.04, Figure 3E). However, this increase in transcript level was not accompanied by an increase in Cyp11β2 protein expression (Figure 3F); a similar dissociation of protein and mRNA levels was observed in mice genetically engineered to produce a more stable Cyp11β2 transcript.30 Thus, we conclude that previously identified causes for autonomous overproduction of aldosterone in humans and in mice, membrane depolarization and enhanced steroidogenic capacity, do not underlie the hyperaldosteronism of T3KO mice.

Altered adrenal responsiveness to Ang II and autonomous production in T3KO mice

Increased responsiveness to Ang II is well-documented in LREH.21–23 We used osmotic mini-pumps to deliver Ang II (0.04–4.0 μg/kg/min) interstitially and measured urinary aldosterone excretion in mice maintained on a NS diet. We found that aldosterone output was dose-dependently increased by Ang II in mice of both genotypes (Figure 4A) and was consistently greater in T3KO than WT (at baseline: WT mean: 8.3 ng-aldo/mg-cre, T3KO mean: 10.5 ng-aldo/mg-cre); therefore, we calculated the fold-increase from baseline for each animal. As shown in Figure 4A, the EC50 for stimulation by Ang II in T3KO mice was left-shifted from that of WT (WT: 2122 ± 235 ng/kg/min, T3KO: 982 ± 112 ng/kg/min; n=4–7 animals/dose; P=0.038). Thus, T3KO mice displayed a hypersensitivity to Ang II. To isolate the Ang II-sensitive component of aldosterone output, and corroborate and extend these findings across the diets, we measured urinary aldosterone excretion before and after candesartan was delivered in the drinking water (10 mg/kg/day). As expected during dietary Na+ restriction, stimulation of the RAS markedly increased the Ang II-evoked component of aldosterone output in mice of both genotypes (P<0.001, Figure 4B, left) but, in T3KO mice this component was nearly twice that seen in WT (P<0.001). In fact, there was a significant effect of genotype across diets; aldosterone production in T3KO mice was approximately double that of WT mice (P<0.001). Thus, we conclude that, as in humans with LREH,21,23 T3KO mice are uncommonly sensitive to the aldosterone-stimulating action of exogenous or endogenous Ang II.

Figure 4.

Changes in aldosterone production evoked by Ang II and candesartan. A, Fold increase in 24hr UAldo/creatinine in WT (white circles) and T3KO mice (black circles) induced by exogenous Ang II delivery (s.c. osmotic mini-pumps: 0 (saline vehicle), 0.04, 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, or 4.0 μg/kg/min; n=4-7 per dose). Changes in aldosterone production evoked by vehicle did not differ from that evoked by 0.04 μg Ang II/kg/min (data not included in the graph). *significant difference in dose-response curves between genotypes (P=0.038); EC50 in T3KO mice was ½ that of WT mice. B, Comparison of Ang II-dependent (left) and independent (right) aldosterone production in WT and T3KO mice on Na+ diets (see Figure 2 for n’s). B, upper left, the Ang II-dependent response defined as difference between the UAldo/creatinine before and during candesartan (C) administration (10mg/kg/day). *indicates main effect of genotype (P=0.002). B, upper right, UAldo/creatinine with candesartan defined as Ang II-independent aldosterone production. B, upper insets, expanded scale to highlight differences between genotypes. Values represent mean ± SEM, *comparison to WT mice (P<0.05).

Lack of aldosterone suppression following salt loading is used as a screening test for PA and is a hallmark of autonomous aldosterone production that is independent of the RAS3. A relative resistance to salt suppression has also been noted in some patients with LREH20,21 underscoring a possible continuum between the two disease states7,8. We used aldosterone output in the presence of candesartan, as a measure of an Ang II-independent component of aldosterone production. We found that candesartan normalized urinary aldosterone excretion between T3KO and WT on LS and NS diets, whereas there was an Ang II-independent component of aldosterone output on HS (P<0.001, Figure 4B, right). These results differ from those seen with T1T3KO mice in which, relative to WT, an enhanced Ang ll-independent component of aldosterone output was evident on all salt diets.15 Thus, we observe that T1T3KO and T3KO mice differ in the degree to which the RAS axis is imbalanced and aldosterone output is autonomous.

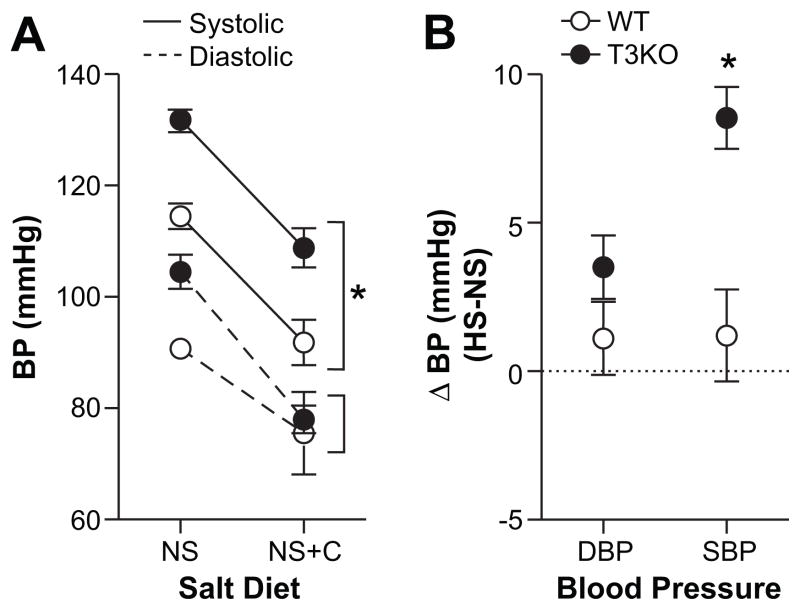

Ang II-dependent and salt-sensitive hypertension in T3KO mice

Relative aldosterone excess as indicated by an elevated ARR is the strongest predictor of DBP and the second-most important predictor of SBP.5 We used candesartan to normalized both aldosterone output and plasma renin concentration between genotypes on a NS diet to determine if the hypertension of T3KO mice could be corrected. In T3KO mice maintained on a NS diet, 24-hr. ambulatory DBP and SBP were elevated, ~13 mmHg (P=0.01) and 17 mmHg (P<0.001), respectively. Candesartan decreased DBP and SBP in mice of both genotypes, but normalized only DBP (Figure 5A). By contrast, SBP of T3KO mice, although corrected to normotensive values, remained elevated 17 mmHg above that of WT (P<0.001) indicating that in T3KO mice factors other than the RAS control SBP.

Figure 5.

The effects of AT1R blockade and high Na+ diet on ambulatory blood pressure. A, 24-hr. SBP (solid lines) and DBP (dashed lines) of WT (white circles) and T3KO (black circles) on NS (n=11) and NS with candesartan in drinking water (n=5–6). Candesartan (10mg/kg/day) normalized DBP between WT and T3KO mice, while SBP remained significantly elevated (*P<0.001). B, Increase in 24-hr. SBPs (solid lines) and DBPs (dashed lines) induced by HS (ΔHS-NS; n=4-6 per condition). SBP and DBP in WT mice failed to respond to HS challenge (n=6), whereas T3KO mice showed increase in SBP (*P<0.001, n=4), but not DBP (P=0.077, n=4). Values represent mean ± SEM, *comparison to WT mice (P<0.05).

Salt-sensitive hypertension is a frequent observation in LREH and a hallmark of volume-dependent hypertension.2 We found that normotensive WT mice were able to adjust to a salt load maintaining normal DBP and SBP during HS challenge (Figure 5B). In T3KO mice, DBP also remained stable during Na+ loading whereas SBP rose by 9 mmHg (P<0.001). This suggests that autonomy of aldosterone production imparts salt-sensitivity that weakens the control of SBP while DBP remains under RAS control.

DISCUSSION

Our studies show that the genetic deletion of TASK-3 subunits produces a phenotype that duplicates key features of human LREH. First, as in LREH, levels of aldosterone output in T3KO mice are mildy elevated but inappropriate for the low levels of plasma renin, resulting in an ARR that is greater than twice that of normotensive WT mice.2,3 Second, on LS and NS aldosterone production remains under the control of RAS with a demonstrated hypersensitivity to both endogenous and exogenous Ang II. An enhanced responsiveness to the steroidogenic actions of Ang II is a well-described characteristic of LREH.20–22 Third, on HS RAS control is weakened revealing a component of aldosterone output that is relatively autonomous, consistent with the relative resistance to salt suppression observed in some patients with LREH.20 Finally, SBP is salt-sensitive in T3KO mice, mimicking yet another established feature of LREH.2

Our mouse model of LREH displays enhanced responsiveness to the actions of Ang II. Candesartan normalized aldosterone production (LS, NS), restored suppressed levels of plasma renin (LS, NS, HS) and corrected the elevation in DBP (NS, HS) between genotypes. This subtle but uniform abnormality in the RAS was unexpected. The adrenal hypersensitivity to Ang ll is likely not the result of an increase in AT1R expression, as message levels for AT1A and AT1B receptors in ZG microdissected from T3KO mice and WT adrenals were equivalent (Figure S2), conclusions that are supported by observations in the Lyon hypertensive rat where neither changes in the affinity nor regulation of Ang Il receptor subtypes in the ZG accounted for enhanced adrenal sensitivity to Ang ll.31 The adrenal hypersensitivity to Ang ll is also not likely the result of an increase in sympathetic nervous system activity (e.g. driving adrenal hyperplasia and/or potentiating aldosterone release), as HR in T3KO mice were reduced significantly from those of WT (Figure S3). In addition, we found no evidence of ZG hyperplasia. Our data also show that neither an increase in the synthetic capacity of the ZG cell to produce aldosterone, as measured by protein levels of Cyp11β2, nor a significant reduction in baseline membrane potential can explain enhanced responsiveness to Ang II. In this respect our data suggest that either TASK-3 channels are not important in setting the baseline membrane potential of ZG cells (in disagreement with previous observations17) or that compensatory expression of other unidentified conductance(s) nmaintain membrane potential in TASK-3 deficient ZG cells.

At present, the precise cellular mechanism that underlies enhanced responsiveness to Ang II remains unanswered. Nevertheless, our mouse models of LREH and IHA suggest an evolution of aldosterone dysregulation, from normal to exaggerated to autonomous, that depends on the absence of TASK-3 (LREH) or both TASK-1 and TASK-3 (IHA). In this respect, it is noteworthy that extracellular K+ acts both alone26 and in concert with Ang II27 to regulate aldosterone production. K+ elevation depolarizes ZG cells permitting the opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and consequent increase in extracellular Ca2+ entry, a step that is critical for sustaining steroidogenesis.32,33 Thus, one could posit that in LREH, a small change in K+ conductance that does not appreciably affect baseline membrane potential may nevertheless render the ZG cell more susceptible to depolarizing influences (i.e. by Ang II), and thus exaggerate responses to submaximal concentrations of aldosterone secretagogues. On the other hand, a larger change in K+ conductance, as demonstrated in our mouse model of IHA, depolarizes the ZG cell and thus imparts autonomy to the production of aldosterone. We propose, therefore, that these mouse models of LREH and IHA stand as proof of principle that progressive loss of K+ channel activity can be a mechanism to advance the syndrome of low renin hypertension.

PERSPECTIVES

IHA and LREH present with a high frequency in hypertension, promoting the development of cardiovascular and renal disease. Here, we demonstrate that disruption of the TASK-3 or TASK-3/TASK-1 genes results in phenotypic characteristics of LREH and IHA in C57BL/6 mice: low renin hypertension with high ARR, hypersensitivity to Ang II and autonomous aldosterone production. These mouse models provide the opportunity to identify the cellular basis for these phenotypic characteristics and suggest that variants in human TASK channel genes may contribute to the development of LREH and IHA. The development of pharmacological agents that increase TASK channel activity may be of therapeutic benefit in the treatment of these hypertensive disorders.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

-

What is New?

First animal model of human low renin essential hypertension

Loss of TASK-3 subunits enhances responsiveness to Ang II

-

What is Relevant?

Progressive loss of TASK channel activity advances the syndrome of low renin hypertension: from IHA to LREH.

Results support the possibility that increased constitutive AT1R activation may play a role in LREH

Results underscore the importance of background K+ leak channels in hypertension.

-

Summary

This is the first study to provide evidence that the genetic deletion of TASK-3 subunits produces a phenotype that duplicates key features of human LREH.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants to P.Q.B. (HL-089717) and grants to D.A.B (NS-33583). We are grateful to Dr. Robert Chevalier and Bobbi Thornhill for sharing their expertise and use of radio-telemetry blood pressure setup.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Funder JW, Carey RM, Fardella C, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Mantero F, Stowasser M, Young WF, Jr, Montori VM. Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with primary aldosteronism: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3266–3281. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon RD, Laragh JH, Funder JW. Low renin hypertensive states: Perspectives, unsolved problems, future research. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulatero P, Verhovez A, Morello F, Veglio F. Diagnosis and treatment of low-renin hypertension. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:324–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stowasser M, Gordon RD. The aldosterone-renin ratio and primary aldosteronism. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:202–203. doi: 10.4065/77.2.202-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomaschitz A, Maerz W, Pilz S, Ritz E, Scharnagl H, Renner W, Boehm BO, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Weihrauch G, Dobnig H. Aldosterone/renin ratio determines peripheral and central blood pressure values over a broad range. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2171–2180. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padfield PL, Brown JJ, Lever AF, Schalekamp MA, Beevers DG, Davies DL, Robertson JI, Tree M. Is low-renin hypertension a stage in the development of essential hypertension or a diagnostic entity? Lancet. 1975;1:548–550. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kater CE, Biglieri EG. The syndromes of low-renin hypertension: “Separating the wheat from the chaff”. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;48:674–681. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302004000500013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim PO, Struthers AD, MacDonald TM. The neurohormonal natural history of essential hypertension: Towards primary or tertiary aldosteronism? J Hypertens. 2002;20:11–15. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200201000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasan RS, Evans JC, Larson MG, Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Rifai N, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Serum aldosterone and the incidence of hypertension in nonhypertensive persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:33–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meneton P, Galan P, Bertrais S, Heudes D, Hercberg S, Menard J. High plasma aldosterone and low renin predict blood pressure increase and hypertension in middle-aged caucasian populations. J Hum Hypertens. 2008;22:550–558. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, Bjorklund P, Zhao B, Nelson-Williams C, Ji W, Cho Y, Patel A, Men CJ, Lolis E, Wisgerhof MV, Geller DS, Mane S, Hellman P, Westin G, Akerstrom G, Wang W, Carling T, Lifton RP. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331:768–772. doi: 10.1126/science.1198785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotshaw DP. Role of membrane depolarization and t-type ca2+ channels in angiotensin ii and k+ stimulated aldosterone secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;175:157–171. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn SJ, Cornwall MC, Williams GH. Electrical properties of isolated rat adrenal glomerulosa and fasciculata cells. Endocrinology. 1987;120:903–914. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-3-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arrighi I, Bloch-Faure M, Grahammer F, Bleich M, Warth R, Mengual R, Drici MD, Barhanin J, Meneton P. Altered potassium balance and aldosterone secretion in a mouse model of human congenital long qt syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8792–8797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141233398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies LA, Hu C, Guagliardo NA, Sen N, Chen X, Talley EM, Carey RM, Bayliss DA, Barrett PQ. Task channel deletion in mice causes primary hyperaldosteronism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2203–2208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heitzmann D, Derand R, Jungbauer S, Bandulik S, Sterner C, Schweda F, El Wakil A, Lalli E, Guy N, Mengual R, Reichold M, Tegtmeier I, Bendahhou S, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Aller MI, Wisden W, Weber A, Lesage F, Warth R, Barhanin J. Invalidation of task1 potassium channels disrupts adrenal gland zonation and mineralocorticoid homeostasis. EMBO J. 2008;27:179–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czirjak G, Enyedi P. Task-3 dominates the background potassium conductance in rat adrenal glomerulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:621–629. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.3.0788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czirjak G, Enyedi P. Formation of functional heterodimers between the task-1 and task-3 two-pore domain potassium channel subunits. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5426–5432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lotshaw DP. Effects of k+ channel blockers on k+ channels, membrane potential, and aldosterone secretion in rat adrenal zona glomerulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4167–4175. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins RD, Weinberger MH, Dowdy AJ, Nokes GW, Gonzales CM, Luetscher JA. Abnormally sustained aldosterone secretion during salt loading in patients with various forms of benign hypertension; relation to plasma renin activity. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:1415–1426. doi: 10.1172/JCI106359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks AD, Marks DB, Kanefsky TM, Adlin VE, Channick BJ. Enhanced adrenal responsiveness to angiotensin ii in patients with low renin essential hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979;48:266–270. doi: 10.1210/jcem-48-2-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisgerhof M, Brown RD. Increased adrenal sensitivity to angiotensin ii in low- renin essential hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:1456–1462. doi: 10.1172/JCI109065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffing GT, Wilson TE, Melby JC. Alterations in aldosterone secretion and metabolism in low renin hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:1454–1460. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-6-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarenko RM, Willcox SC, Shu S, Berg AP, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Talley EM, Chen X, Bayliss DA. Motoneuronal task channels contribute to immobilizing effects of inhalational general anesthetics. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7691–7704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1655-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guagliardo NA, Yao J, Bayliss DA, Barrett PQ. Task channels are not required to mount an aldosterone secretory response to metabolic acidosis in mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;336:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dluhy RG, Axelrod L, Underwood RH, Williams GH. Studies of the control of plasma aldosterone concentration in normal man. Ii. Effect of dietary potassium and acute potassium infusion. J of Clin Invest. 1972;51:1950–1957. doi: 10.1172/JCI107001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pratt JH. Role of angiotensin ii in potassium-mediated stimulation of aldosterone secretion in the dog. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:667–672. doi: 10.1172/JCI110661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wotus C, Levay-Young BK, Rogers LM, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Engeland WC. Development of adrenal zonation in fetal rats defined by expression of aldosterone synthase and 11beta-hydroxylase. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4397–4403. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulkroun S, Samson-Couterie B, Dzib JF, Lefebvre H, Louiset E, Amar L, Plouin PF, Lalli E, Jeunemaitre X, Benecke A, Meatchi T, Zennaro MC. Adrenal cortex remodeling and functional zona glomerulosa hyperplasia in primary aldosteronism. Hypertension. 2010;56:885–892. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Makhanova N, Hagaman J, Kim HS, Smithies O. Salt-sensitive blood pressure in mice with increased expression of aldosterone synthase. Hypertension. 2008;51:134–140. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aguilar F, Lo M, Claustrat B, Saez JM, Sassard J, Li JY. Hypersensitivity of the adrenal cortex to trophic and secretory effects of angiotensin ii in lyon genetically-hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2004;43:87–93. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107194.44040.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aguilera G, Catt KJ. Participation of voltage-dependent calcium channels in the regulation of adrenal glomerulosa function by angiotensin ii and potassium. Endocrinology. 1986;118:112–118. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-1-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrett PQ, Bollag WB, Isales CM, McCarthy RT, Rasmussen H. Role of calcium in angiotensin ii-mediated aldosterone secretion. Endocr Rev. 1989;10:496–518. doi: 10.1210/edrv-10-4-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.