Abstract

Applied behavior analysts encounter situations in which private events hinder client progress, and additional techniques to address these issues are needed. By conceptualizing private events as verbal rules, we provide a behavior-analytic framework for understanding and addressing these events. Relational frame theory (RFT) is the basis for this conceptual foundation; the empirically based principles of RFT are presented along with direct implications for understanding private events. Defusion, an RFT-based technique for addressing private events, is then described and empirical studies that evaluate the effects of defusion are reviewed. Finally, potential clinical applications for practicing behavior analysts are offered.

Keywords: defusion, emotions, fusion, private events, thoughts

A behavior analyst is consulting with a parent of a child diagnosed with autism who tantrums at the grocery store. The behavior analyst suggests a treatment package consisting of escape extinction, in which the parent is asked to refrain from leaving the grocery store during a tantrum. While attempting to implement this intervention, the parent thinks to himself, “If I just stand here and let him tantrum, everyone will think I am a horrible parent and that would be humiliating.” It is very likely that this private event affects whether the parent continues to implement the intervention, and therefore may be of interest to behavior analysts.

Contingency-Shaped and Rule-Governed Behavior

In a thorough conceptual paper, Allen and Warzak (2000) described a functional-analytic approach to identifying the variables that influence parental adherence to recommended treatments. The authors identify and describe four categories of variables that can impact parental adherence, including establishing operations, stimulus generalization, response acquisition, and consequent events. Absent from this analysis, however, was the potential impact of difficult private events highlighted by the previous scenario. The role that private events, such as thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations, should play in an analysis of behavior has been a contentious issue (e.g., Anderson, Hawkins, Freeman, & Scotti, 2000; Flora & Kestner, 1995; Friman, Hayes, & Wilson, 1998; Lamal, 1998; Palmer, 2004; Stemmer, 1995). Although we cannot access or directly analyze private events, behavior analysis may be at a point in which a discussion about the importance of acknowledging, talking about, and demonstrating an understanding of private events with our clients, from an informed and scientifically validated standpoint, can be extended to the scrutiny of empirical data. In so doing, we may begin to “apply” our science (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968) to socially significant behavior change in all domains, including inferred private ones, while staying true to our scientific ideals.

Rule-governed behavior is an area of behavior analysis that informs the issue of private events. Although a theoretical analysis of rule-governed behavior is beyond the scope of the present paper, interested readers are directed to discussions by Hayes, Zettle, and Rosenfarb (1989), Schlinger and Blakely (1987), and Barnes-Holmes, O'Hara, Roche, Hayes, Bissett, & Lyddy (2001). What is critical to the present paper is the distinction between contingency-shaped and rule-governed behavior. Contingency-shaped behavior is controlled by direct exposure to nonverbal contingencies, such as when a young child touches a hot stove, experiences a painful burn, and does not touch the stove again. In contrast, when a young child hears the rule, “If you touch a hot stove, you will get burned” and does not touch the hot stove, this behavior is said to be rule-governed. The child's behavior is not under the control of the consequences that follow touching a hot stove (i.e., getting burned); instead, it is under the control of a verbal rule specifying the contingency between the behavior and its consequence. It is suggested that rules are followed as a result of two separate learning histories: (a) a history of the correspondence between the contingencies described by rules and the rules themselves, and (b) a history of social reinforcement for rule-following in general (Allen & Warzak, 2000; Hayes & Wilson, 1993). As described later in this paper, it has been suggested that novel rules derive their function through other verbal means (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001).

Rules are useful for a variety of reasons: they can change behavior more quickly than direct contingencies; they allow individuals to behave effectively with regard to contingencies with delayed consequences; and they help individuals avoid contingencies that, if contacted even once, could be destructive or lethal. However, despite their utility, rules can also be detrimental. Research has demonstrated that there are circumstances in which rule-governed behavior is less sensitive to contingency changes than contingency-shaped behavior (Vaughan, 1989). In one study, researchers trained all participants to complete the same task: half were trained with a shaping procedure, the other half were trained with a set of verbal rules, and task completion was reinforced for both groups (Hayes, Brownstein, Haas, & Greenway, 1986). When the reinforcement contingencies were later modified, the behavior of only one half the participants that had been trained by rules changed to match the new contingencies. Overall, the participants in this group engaged in rates of behavior that were inconsistent with the schedule of reinforcement. In contrast, the behavior of the entire shaping group changed to match the altered contingencies. The fact that rule-governed behavior is relatively less sensitive to environmental contingencies than contingency-shaped behavior has important clinical implications for behavior analysts because it means that client behavior is sometimes more heavily influenced by verbal rules than external contingencies.

Rules do not have to be imposed upon humans by others: rules that are self-generated function in similar ways.

Rules do not have to be imposed upon humans by others: rules that are self-generated function in similar ways. A self-rule may be a repetition of a rule stated directly by the verbal community, such as when a child who has never touched a hot stove repeats a previously stated rule to herself (e.g., “Don't touch the stove or you'll get burned”). A self-rule can also be derived from an individual's direct history of environmental contingencies: a child who has touched a hot stove may generate the previous rule by tacting the contacted contingency (Poppen, 1989). In an empirical evaluation of self-generated rules, Rosenfarb, Newland, Brannon, and Howey (1992) found that participants who were asked to generate their own rules about reinforcement contingencies came under the control of the actual schedules of reinforcement quicker, but were relatively less sensitive to subsequent extinction, than participants who were not asked to generate rules. The study also included a group of participants who were given external rules about the reinforcement contingencies. Patterns of responding for this group were very similar to the self-generated rule group, suggesting that external rules and self-generated rules may have similar effects on behavior.

Consider again the example of the parent in the grocery store. The thought, “If I just stand here and let him tantrum, everyone will think I am a horrible parent, and that would be humiliating” is a self-generated rule describing a contingency involving social disapproval as a consequence. If social disapproval functions as a punisher for this parent, it is unlikely that he will implement the extinction procedure. If extinction is never implemented, the parent's behavior will never be influenced by the actual consequences of extinction (i.e., eventual decreases in the child's tantrums). By following this self-generated rule, the parent's behavior (i.e., not implementing extinction) is negatively reinforced because he is avoiding the aversive event (i.e., social disapproval) described by the rule. However, this occurs in the absence of direct contact with environmental contingencies. This illustrates how rules, which specify contingencies of reinforcement and punishment (e.g., “If I avoid implementing extinction, I will avoid embarrassment”), may serve as stimuli that influence overt behavior.

While discussing the intervention with the behavior analyst, the parent may state that the rule is a barrier to implementing the extinction procedure. Behavior analysts might respond to this type of situation by reiterating the effectiveness of the intervention (e.g., “If you keep working on it, it will get better”), by selecting an alternative intervention (e.g., providing noncontingent reinforcement during trips to the grocery store), or clarifying the significance of the selected target behavior (e.g., “Is taking trips to the grocery store a primary goal right now? Is there another behavior you'd rather target at this point in time?”). However, it is not clear that the parent's behavior will be more sensitive to the behavior analyst's rule (regarding the eventual effectiveness of extinction) than their own self-generated rule regarding social disapproval. Further, alternative interventions might not be available or as effective as the original procedure, or may have other undesirable side effects. Additionally, it is likely that the parent will continue to contact similar private events in different contexts. Defusion, which is based on relational frame theory, offers an alternative approach to the treatment of these types of maladaptive self-generated rules. Defusion and its use in applied situations will be covered in the remainder of the paper.

Relational Frame Theory

Relational frame theory (RFT; Hayes et al., 2001) is a behavior-analytic account of language and cognition that is intended to account for the generativity of complex human behavior. The basic tenet is that relations are derived among stimuli, and stimuli are responded to based on those relations: the term for this is derived relational responding. Derived relational responding refers to the process of relating stimuli according to an arbitrary contextual cue that is not based on the physical characteristics of the stimuli. For example, if an individual is taught that the written word c-a-r goes with the spoken word, “car,” and that the spoken word “car” goes with an actual car, then it will be derived that the written word c-a-r goes with the actual car. The relation between the written word and the actual car is considered derived because the relation has not been directly trained. Behavior analysts recognize this type of stimulus-stimulus relation as stimulus equivalence (Sidman, 1971); however, research has shown that many other types of relations, such as opposition, more/less, and first/then—which do not fit neatly with the stimulus equivalence paradigm—can also be learned (Dymond & Barnes, 1995; Steele & Hayes, 1991).

Relational framing is the term for patterns of derived relational responding that share the properties of mutual entailment, combinatorial entailment, and the transformation of stimulus functions. To illustrate these properties, consider an example of the relation between two stimuli (e.g., a grocery store and a convenience store), when a child engages in self-injurious behavior. Given the relation, “it is less embarrassing to be in the convenience store than the grocery store,” the relation will be derived in the reverse direction as “it is more embarrassing to be in the grocery store than the convenience store.” This property is called mutual entailment. Combinatorial entailment occurs when relations emerge among stimuli that have never been paired. Given the previous relation along with, “it is less embarrassing to be in the grocery store than the mall,” the relation between the convenience store and the mall will be derived based on the relation of each of these stimuli to the grocery store. Mutual entailment and combinatorial entailment are under the control of contextual cues. In this example, the phrase “more than/less than” may function as a contextual cue specifying the relation between the stimuli. The word, “embarrassing,” may serve as another contextual cue specifying the consequential functions of the stimuli. The overall context in which framing occurs is also an important component of this analysis: in a different situation (e.g., purchasing a new shirt), the relations among these stimuli would be different.

The third component of relational framing, transformation of stimulus function, is most relevant to the topic of interfering private events. A transformation of stimulus function has occurred when the function of one stimulus is transformed because of its relation with other stimuli. In basic laboratory studies, researchers have demonstrated that novel stimuli can acquire reinforcing and punishing (Hayes, Kohlenberg, & Hayes, 1991; Whelan & Barnes-Holmes, 2004; Whelan, Barnes-Holmes, & Dymond, 2006), discriminative (Dymond & Barnes, 1995), respondent eliciting (Dougher, Hamilton, Fink, & Harrington, 2007), and avoidance-evoking (Auguston & Dougher, 1997; Dymond, Roche, Forsyth, Whelan, & Rhoden, 2007) functions through relational frames. As with the other features of relational framing, researchers have determined that this process is influenced by contextual cues (Dougher, Perkins, Greenway, Koons, & Chiasson, 2002; Roche, Barnes-Holmes, Smeets, Barnes-Holmes, & McGeady, 2000; Steele & Hayes, 1991). The transformation of stimulus functions helps to explain why language and rule-governed behavior are so advantageous for verbal humans, but also why they can be problematic. The functions of stimuli transform based on verbally specified relations to other stimuli without the individual ever directly contacting contingencies of reinforcement or punishment.

To illustrate the transformation of stimulus functions in an applied situation, recall the previous example regarding a child's self-injurious behavior. Given the caregiver's history, going to the grocery store is aversive when she is accompanied by her child who engages in self-injurious behavior. Now suppose that an important family event, such as a wedding, is more formal than the grocery store, and for this caregiver, in the context of the child's self-injurious behavior, more formal than is related to more embarrassing than. The caregiver has never directly experienced the child's behavior at a wedding, but it has acquired a highly aversive function based on its relation to the grocery store in this context. The wedding functions as an aversive stimulus in terms of self-injury based solely on its relation to the grocery store. As a result, the caregiver may avoid taking the child to the wedding and miss an important family event. However, the only way for the caregiver to know which setting is more aversive is to directly experience both. In terms of direct contingencies, the wedding may actually be less aversive because, given that the wedding will be attended by close friends and loved ones who are familiar with the child's disability, social disapproval may be less embarrassing there than at the grocery store. However, as a result of relational framing, the self-generated rule “the wedding is more embarrassing than the grocery store in terms of self-injurious behavior,” may result in a choice not to attend the wedding.

Fused responses are under the control of the derived properties of stimuli (e.g., verbal rules) rather than a history of direct contact with them (e.g., direct contingencies). Fused responses are advantageous in many contexts but detrimental in others. For example, suppose that the caregiver from the previous example has stated that she wants to take her child to family events. If the caregiver's actions are controlled by the rule, “it is more embarrassing to be at a wedding than at a grocery store when my child engages in self-injurious behavior,” she will likely avoid the wedding, despite this being contrary to her stated goal. If this thought occurs in a highly fused verbal context it will have a strong effect on behavior, whereas, if it occurs in a defused verbal context it can be experienced as “just a thought” and not affect behavior. Based on RFT and the accompanying empirical research, the variables that influence relational framing and its properties (most importantly, the transformation of stimulus function) can be manipulated to disrupt rule-governance in a process termed defusion.

Defusion: Targeting the Function of Private Events

Defusion exercises are designed to interrupt fusion by decreasing the control of rules and increasing contact with direct contingencies. As an RFT interpretation suggests, defusion targets the function of interfering private events in order to reduce their impact. Given research that has demonstrated that the transformation of stimulus functions is under contextual control, defusion exercises involve manipulating the context in which the stimulus is experienced and providing the individual with opportunities to contact the stimulus in unconventional ways that separate the physical stimulus functions from derived stimulus functions (Blackledge, 2007; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). Like reinforcement, defusion is functionally defined and can only be confirmed based on subsequent changes in behavior.

In addition to having behavior-analytic theoretical underpinnings and notable basic research supporting its conceptualization, there is a considerable amount of evidence suggesting that defusion is a useful strategy for reducing the impact of problematic private events. In the following section, we describe two specific defusion exercises in terms of how they can disrupt fusion by changing contextual cues, briefly review two studies investigating the effectiveness of these exercises, and provide a short summary of the current state of defusion literature.

The Milk, Milk, Milk Exercise

One defusion exercise that researchers have evaluated in isolation is the Milk, Milk, Milk exercise (word repetition; Titchener, 1916). The point of this exercise is to bring the client into contact with the direct properties of a stimulus; properties that can initially be less salient than the derived functions. This exercise begins with reporting what comes to mind when the word “milk” is said. Usually the derived functions of the word are reported (e.g., “it's cold and white, you drink it”). It is noted that many functions of the stimulus are present even though actual milk is not, illustrating the extent to which the verbal stimulus has acquired the functions of the tangible stimulus. The client is then asked to repeat the word, “milk,” aloud for 1–2 min. Clients often report that, following word repetition, the direct stimulus functions of the word, such as auditory properties or muscle movements, are now more prominent than the derived functions. This brief exercise allows clients to experience how changing the context (i.e., repeating the word aloud) can alter the function of the verbal stimulus. The derived functions of the stimulus are not eliminated, but as a result of the exercise, multiple different functions have been contacted (Hayes et al., 1999). In addition to being something one drinks, “milk” is also a sound. Following this experiential exercise with “milk,” the client repeats the above steps with a problematic private event. For example, consider a teacher who has the thought, “This is too hard,” in response to being asked to follow through on a demand. He might be asked to repeat the phrase (“It is too hard to follow through on a demand”) aloud several times, and to notice that in addition to being a thought that is contacted as a rule (e.g., derived verbal functions), it is also just a stimulus that has specific auditory properties (e.g., direct stimulus functions).

Masuda et al. (2010) compared the effects of the Milk, Milk, Milk Exercise (i.e., word repetition), thought distraction (training in procedures to think about other thoughts), and a distraction control (reading an unrelated article) on the reported believability and discomfort of negative private events in a group design. Thought distraction was chosen as a control condition because it represented a technique that is commonly used by lay people and the distraction control condition functioned as a control for the effects of participating in the study. The target private event was chosen by the participant and included thoughts such as “I am ugly” and “I am stupid.” Believability (i.e., how believable the private event was) and discomfort (i.e., how uncomfortable the private event was) were measured via self-report on Likert-type scales ranging from 0 to 100. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions, and a subset of participants with elevated depressive symptoms were analyzed to evaluate the effects on a clinical population. Participants in the word repetition condition reported statistically greater reductions in believability and discomfort than participants in the other two conditions. Further, these effects were evident in participants with and without depressive symptoms. This study suggests that word repetition is an effective strategy for reducing the influence of problematic thoughts.

The Cards Game and Swamp Metaphor

Another defusion exercise, the Cards Game (Hayes et al., 1999), emphasizes that private events are separable from overt behavior. In this exercise, the individual is asked to write a few uncomfortable thoughts on index cards. The individual is then given a folded piece of paper and asked to walk around the room. After walking around the room, the individual opens the piece of paper and finds the words “I can't stand” written on it. The individual is asked to imagine if, when presented with one of his or her uncomfortable thoughts, he or she could continue with a given task despite the content of those uncomfortable thoughts. Through this exercise, the individual contacts the fact that private events and actions are related only temporally and not causally. In other words, a particular private event can occur without it governing behavior as a rule. In RFT terms, the function of the private event has transformed from a rule that controls behavior to a stimulus that the individual can respond to in a number of different ways, including not at all. The individual would then be encouraged to recall this exercise, specifically the experience of having a private event that does not control subsequent overt behavior, when a difficult or painful private event occurs.

Some defusion exercises have been empirically evaluated in combination with acceptance-based exercises. Acceptance-based exercises, which promote a willingness to experience uncomfortable private events, are contrasted with control-based strategies, which attempt to alter the content or frequency of private events. Acceptance and defusion work together, in that both seek to decrease the impact of nonfunctional rule-governance to allow individuals to reach desired goals. A common acceptance metaphor is the Swamp Metaphor (Hayes et al., 1999), in which the individual is asked to identify an important goal. In order to reach the goal, the individual must cross a muddy swamp, which is analogous to the behaviors the individual has to engage in to reach the goal and the difficult private events that will occur along the way. After noting the uncomfortable thoughts and feelings about crossing the swamp, the individual is instructed that the best way to cross the swamp and reach their goal is to observe the uncomfortable private events without attempting to change them—just like one cannot change the make-up of the swamp.

Gutierrez, Luciano, Rodriguez, and Fink (2004) evaluated a combined acceptance and defusion protocol, including the Swamp Metaphor and the Cards Game. Participants were randomly assigned to the acceptance-defusion protocol or a control-based protocol (training in techniques to manage or regulate pain-related thoughts). Both groups were asked to engage in a task, once before and once after receiving the assigned protocol, in which correct responses produced tokens and electric shocks. Following each shock presentation, participants were given the option to either continue or stop the task. The dependent measures included pain tolerance, or the number of shocks administered before the participant chose to quit the task, as well as pain believability, or the degree to which self-reported pain level corresponded with task-continuation. In this study, fusion is characterized by choosing to stop the task immediately after reporting “very much pain,” (i.e., high pain literality) and defusion by continuing to engage in the task despite reporting “very much pain” (i.e., low pain literality). Thus, this study allowed for the evaluation (using direct observation) of the effects of the fusion protocol on overt nonverbal behavior (rather than indirect measurement of private verbal behavior). For participants who self-administered larger shock magnitudes (a subset of the entire group), the pain tolerance of 70% of the acceptance-defusion group increased following the protocol; the pain tolerance of about 10% of the control-based group increased. The acceptance-defusion group also reported lower overall pain believability (how literally they experienced pain-related thoughts).

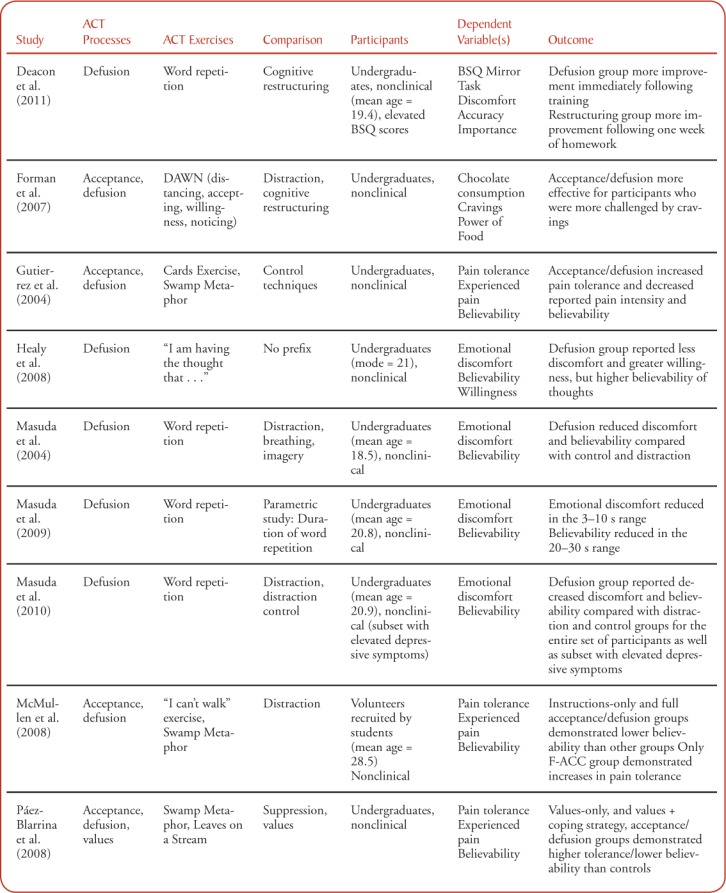

These studies highlighted how two different defusion exercises impact the extent to which private events (a) are reported as literal events, (b) produce discomfort, and (c) correlate with overt behavior. Similar findings have resulted from additional studies in which researchers evaluated the efficacy of defusion alone (Deacon, Fawzy, Lickel, & Wolitzky-Taylor, 2011; Healy et al., 2008; Masuda, Hayes, Sackett, & Twohig, 2004; Masuda et al., 2009; Masuda et al., 2010) or in combination with acceptance metaphors (Forman et al., 2007; Gutierrez et al., 2004; McMullen et al., 2008; Páez-Blarrina et al., 2008). Reviewing the complete defusion literature is outside the purview of this paper; however, the table provides an overview of each of these studies, including the defusion exercise, population, dependent variables, and outcomes. Notably, four of the nine studies reviewed in the table include an objective measure (i.e., number of self-administered shocks or duration of time spent in presence of desired food without consuming it) as a dependent variable. However, the remaining five studies rely solely on more traditional clinical methodology, including self-report and group design. From a behavior-analytic standpoint, the reliance on self-report may be viewed as a limitation of the current research, and future researchers should attempt to include more objective measures of the effects of defusion. Nevertheless, we suggest that these findings might be of interest to behavior analysts with clients who respond to private events in dysfunctional ways (e.g., by emitting maladaptive behavior that is governed by self-generated verbal rules).

Although the preceding studies are somewhat translational in that the researchers studied nonclinical populations in tightly controlled settings, the effects of defusion have been documented as a component of a larger treatment package called acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 1999). ACT is a functional, experiential approach to changing behavior that is based on an RFT interpretation of language and rule-governance. A discussion of ACT can be found elsewhere (Hayes et al., 1999; Luoma, Hayes, & Walser, 2007); for the purposes of the present paper, we wish to emphasize that ACT has a large research base (for a review, see Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006) with a variety of populations across settings. Additionally, one study (Blackledge & Hayes, 2006) evaluated the impact of an ACT workshop on reported stress levels of parents with autism. Blackledge and Hayes reported statistically significant improvements on measures of distress, depression, and general psychiatric health from preintervention to postintervention and at a 3-month follow-up. The studies reviewed here that have isolated the effects of defusion in basic laboratory settings, combined with applied research on the entire ACT treatment package, suggest that these exercises can effectively reduce the extent to which dysfunctional self-rules control behavior.

Table.

Summary of Defusion Studies

Suggestions for Using Defusion With Clients

As the preceding examples illustrate, behavior analysts sometimes encounter scenarios in which clients report that private events are hindering their progress or implementation of prescribed programs. For example, the parent attempting to carry out extinction in the grocery store may report to the behavior analyst that thoughts about social disapproval interfere with his implementation of the intervention. In these cases, a defusion exercise may assist the client in noting that the private event is just that: a self-generated rule that may or may not align with direct contingencies. It is always important that professionals practice within their areas of competency and professional restrictions, and therefore these procedures are probably most applicable to typical, run-of-the-mill thoughts such as those described herein. Situations where the private events are outside one's area of competency should be referred to the appropriate professional. This line will vary depending on one's competency and license, but can include private events that do not pertain to the target behaviors for which the behavior analyst was hired (e.g., marital problems, suicidal thoughts) or some diagnosable disorders (e.g., panic disorder). Nevertheless, it is likely that most or all verbally competent clients will at some point present with private events that interfere with treatment. In those cases, behavior analysts are frequently left no choice but to use commonsense strategies, such as reiterating the effectiveness of the intervention, selecting an alternative intervention, or clarifying the significance of the target behavior. In contrast, defusion is behaviorally based and has a considerable amount of evidence suggesting that it can reduce the influence of interfering private events.

General Guidelines

It is probably more important that behavior analysts understand the aim of defusion exercises rather than being familiar with any one technique. This is parallel to the importance of understanding why extinction works versus only knowing how to withhold a specific reinforcer for a particular target behavior. The goal of defusion exercises is to reduce the influence of target private events. There is very little concern for the effects of defusion exercises on the form or frequency of a particular private event. Rather, the focus is on how the individual responds to the private event. For example, defusion exercises are designed to help individuals come into contact with the direct properties of self-generated rules rather than immediately responding to the derived properties. For example, a defusion exercise may be useful for a parent who experiences the private event “this intervention is too hard” and responds to the private event by engaging in alternative responses, other than implementing the intervention protocol. Instead of attempting to help the parent stop having the thought, be more motivated to engage in the intervention, or distract himself from the thought, defusion exercises seek to change the way the parent responds to the private event. For example, if a parent says, “This intervention is too hard,” the behavior analyst might be better off encouraging the parent to consider different ways of responding to the rule (i.e., engaging in a defusion exercise) rather than challenging the accuracy of the rule itself (e.g., “It will get easier the more you work on it”). Essentially, the behavior analyst is communicating that the difficult private event can be experienced in a number of ways, and does not have to function as a rule that governs behavior.

Defusion is perhaps best conceptualized as a way that individuals respond to private events. Because the types of thoughts referred to in this paper are nonclinical (e.g., not based on a diagnosable psychological disorder or thoughts commonly seen by a clinical psychologist), the use of a simple defusion self-statement or the reminder of a simple exercise might be sufficient to keep the individual from responding to the target thought as a rule. Depending on the private event and the situation in which it occurs, it may be necessary for the client to engage in the defusion exercise in context when the problematic private event occurs. For others, practicing defusion exercises out of context will prepare the client to respond to difficult private events differently when they do arise.

The behavior analyst has a wide array of defusion exercises to choose from; recall that defusion is defined functionally, not topographically, and that any process that serves to undermine rule-governance by altering the function of a verbal stimulus may be termed defusion. A large number of defusion exercises have been developed and made available to clinicians in books (Hayes et al., 1999; Luoma et al., 2007) and online (contex-tualpsychology.org); in the previous section, two empirically-validated exercises were described with clinical examples detailing how they might specifically apply to the work of behavior analysts. In this section, we offer some general guidelines for implementing defusion, describe two additional defusion exercises, and provide considerations for practical application by behavior analysts.

“I Am Having the Thought That . . .”

At the beginning of the paper, a scenario was described wherein a parent had the thought, “If I just stand here and let him tantrum, everyone will think I am a horrible parent,” when attempting to implement extinction of escape-maintained tantrum behavior at the grocery store. If the parent reports that this private event impeded her implementation of the intervention, a brief defusion exercise may assist the client in noting that the private event is just that: a self-generated rule that may or may not align with direct contingencies. One exercise that emphasizes this distinction involves placing the prefix, “I am having the thought that,” (Healy et al., 2008) before the problematic private event. Like other defusion exercises, the prefix transforms the function of the thought from a rule that is responded to literally to a stimulus that may or may not impact future behavior. The behavior analyst may encourage the parent to say this prefix, either covertly or overtly, prior to saying the thought. In describing the purpose to the parent, the behavior analyst may say something like, “Sometimes we respond to our thoughts as if they describe the real-world. This exercise helps you to remember that a thought is just a thought, and that it doesn't necessarily line up with what is actually going to happen.” Across all of the defusion exercises, it is important to encourage clients to practice the strategy and observe whether or not it has an impact on behavior. Following up, the behavior analyst should check in to evaluate if the addition of the prefix has loosened the control of the self-generated rule and allowed the parent to engage in desirable behaviors that contact direct contingencies.

Passengers on the Bus

Another common defusion exercise is the Passengers on the Bus Metaphor (Hayes et al., 1999), which encourages clients to conceptualize aversive and unwanted thoughts as obnoxious passengers on a bus. Although these passengers act menacing, make frequent demands to stop the bus or change its direction, threaten to physically harm the client, and masquerade as the entities in charge, the only person on the bus who actually has the power to control the bus is the driver (i.e., the client). As the “driver,” the client gets to choose the route the bus takes, but they do not get to choose who gets on or what they say. Time spent attempting to get rid of the passengers is time lost progressing toward desired goals.

A direct care staff may experience private events about the complexity and intensity of functional communication training with an adult client. The individual may have thoughts like, “There are too many steps, I can't remember all of them,” “If I don't do it perfectly, the client's behavior won't improve at all,” and “I'm no good at this job anyway.” With all of these negative private events occurring, the Passengers on the Bus metaphor might be an appropriate exercise for this situation. In using the metaphor, the behavior analyst first describes how the staff member is similar to the driver of a bus, moving toward his goal of helping the client. The difficult private events are akin to noisy passengers who try to get the driver to stop or change directions, but only the driver controls where the bus goes. Only the client gets to decide if he stays on the path toward his goals. The “passengers” (i.e., private events) do not control the bus. In more technical terms, the function of the private events can be transformed via this metaphor from stimuli that control behavior (i.e., rules) to stimuli that, while present, do not necessarily evoke or elicit behavior. Again, the behavior analyst should encourage the staff to practice conceptualizing private events in this manner and to note if the exercise has effectively reduced the control of these private events.

Summary

RFT provides a behavior-analytic framework for understanding the nature of language and private events. From this perspective, it is possible to account for the ways in which language benefits and burdens humans. Although language allows us to engage in functional rule-governed behavior, thereby solving complex problems and avoiding contingencies with dangerous consequences, it can also interfere when our behavior is controlled to a greater extent by faulty rules than by direct contingencies.

Behavior analysts may encounter scenarios in which rule-governed responses to private events impede client progress or affect a client's quality of life. Defusion, an intervention that is based on an RFT interpretation of complex language and has growing empirical support, offers behavior analysts a conceptually-systematic way to alter the function of these private events. Although researchers should continue to expand the scope of defusion research, with an emphasis on the development of objective measurement strategies, current results suggest that it effectively decreases the control and aversiveness of dysfunctional rules. From our perspective, this research, combined with clinical ACT research, makes a strong case that defusion can be effective for a wide variety of populations struggling with private events. It is our hope that behavior analysts will consider implementing and systematically evaluating the defusion techniques described previously when clients report that difficult or painful private events are impacting their implementation of treatments and interventions.

Footnotes

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Tim Slocum's contribution to the conceptualization of this manuscript.

Action Editor: Michael Himle

References

- Allen K. D, Warzak W. J. The problem of parental nonadherence in clinical behavior analysis: Effective treatment is not enough. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:373–391. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Hawkins R, Freeman K, Scotti J. Private events: Do they belong in a science of human behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF03391995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustson E. M, Dougher M. J. The transfer of avoidance evoking functions through stimulus equivalence classes. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1997;28:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(97)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer D. M, Wolf M. M, Risley T. R. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, O'Hara D, Roche B, Hayes S.C, Bissett R.T, Lyddy F. Understanding and verbal regulation. In: Hayes S. C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational Frame Theory. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge J. T. Disrupting verbal processes: Cognitive defusion in acceptance and commitment therapy and other mindfulness-based psychotherapies. The Psychological Record. 2007;57:555–576. [Google Scholar]

- Blackledge J. T, Hayes S. C. Using acceptance and commitment training in the support of parents of children diagnosed with autism. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2006;28:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon B. J, Fawzy T. I, Lickel J. J, Wolitzky-Taylor K. B. Cognitive defusion versus cognitive restructuring in the treatment of negative self-referential thoughts: An investigation of process and outcome. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2011;25:218–232. [Google Scholar]

- Dougher M. J, Hamilton D. A, Fink B. C, Harrington J. Transformation of the discriminative and eliciting functions of generalized relational stimuli. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;88:179–197. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.45-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougher M, Perkins D. R, Greenway D, Koons A, Chiasson C. Contextual control of equivalence-based transformation of functions. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:63–94. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Barnes D. A transformation of self-discrimination response functions in accordance with the arbitrarily applicable relations of sameness, more than, and less than. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1995;64:163–184. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Roche B, Forsyth J. P, Whelan R, Rhoden J. Transformation of avoidance response functions in accordance with same and opposite relational frames. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;88:249–262. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.22-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora S, Kestner J. Cognitions, thoughts, private events, etc. are never initiating causes of behavior: Reply to Overskied. The Psychological Record. 1995;45:577–589. [Google Scholar]

- Forman E. M, Hoffman K. L, McGrath K. B, Herbert J. D, Brandsma L. L, Lowe M. R. A comparison of acceptance- and control-based strategies for coping with food cravings: An analog study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2372–2386. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friman P. C, Hayes S. C, Wilson K. G. Why behavior analysts should study emotion: the example of anxiety. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:137–156. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez O, Luciano C, Rodr'guez M, Fink B. C. Comparison between an acceptance-based and a cognitive-control-based protocol for coping with pain. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:767–784. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Brownstein A. J, Haas J. R, Greenway D. E. Instructions, multiple schedules, and extinction: Distinguishing rule-governed from schedule-controlled behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1986;46:137–147. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1986.46-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Kohlenberg B. K, Hayes L. J. The transfer of specific and general consequential functions through simple and conditional equivalence classes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991;56:119–137. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.56-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Luoma J. B, Bond F. W, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Strosahl K. D, Wilson K. G. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Wilson K. G. Some applied implications of a contemporary behavior-analytic account of verbal events. The Behavior Analyst. 1993;16:283–301. doi: 10.1007/BF03392637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Zettle R. D, Rosenfarb I. Rule-following. In: Hayes S. C, editor. Rule-governed behavior: Cognition contingencies, and instructional control. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Healy H, Barnes-Holmes Y, Barnes-Holmes D, Keogh C, Luciano C, Wilson K. An experimental test of a cognitive defusion exercise: Coping with negative and positive self-statements. The Psychological Record. 2008;58:623–640. [Google Scholar]

- Lamal P. A. Advancing backwards. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:705–706. [Google Scholar]

- Luoma J. B, Hayes S. C, Walser R. D. Learning ACT: An acceptance & commitment therapy skills-training manual for therapists. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger : Context Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, Hayes S. C, Sackett C. F, Twohig M. P. Cognitive defusion and self-relevant negative thoughts: Examining the impact of a ninety year old technique. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, Hayes S. C, Twohig M. P, Drossel C, Lillis J, Washio Y. A parametric study of cognitive defusion and the believability and discomfort of negative self-relevant thoughts. Behavior Modification. 2009;33:250–262. doi: 10.1177/0145445508326259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, Twohig M. P, Stormo A. R, Feinstein A. B, Chou Y, Wendell J. W. The effects of cognitive defusion and thought distraction on emotional discomfort and believability of negative self-referential thoughts. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2010;41:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen J, Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Stewart I, Luciano C, Cochrane A. Acceptance versus distraction: Brief instructions, metaphors, and exercises in increasing tolerance for self-delivered electric shocks. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Páez-Blarrina M, Luciano C, Gutierrez-Martinez O, Valdivia S, Ortega J, Valverde M. The role of values with personal examples in altering the functions of pain: Comparison between acceptance-based and cognitive-control-based protocols. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer D. C. Dialogue on private events. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2004;20:111–128. doi: 10.1007/BF03392998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppen R. L. Some clinical implications of rule-governed behavior. In: Hayes S. C, editor. Rule-governed behavior: Cognition contingencies, and instructional control. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 325–357. [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Barnes-Holmes D, Smeets P. M, Barnes-Holmes Y, McGeady S. Contextual control over the derived transformation of discriminative and sexual arousal functions. The Psychological Record. 2000;50:267–292. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfarb I. S, Newland M, Brannon S. E, Howey D. S. Effects of self-generated rules on the development of schedule-controlled behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1992;58:107–121. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1992.58-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger H, Blakely E. Function-altering effects of contingency-specifying stimuli. The Behavior Analyst. 1987;10:41–45. doi: 10.1007/BF03392405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Reading and auditory-visual equivalences. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1971;14:5–13. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1401.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele D, Hayes S. C. Stimulus equivalence and arbitrarily applicable relational responding. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991;56:519–555. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.56-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer N. Explanatory and predictive roles of inner causes: A reply to Overskied. The Psychological Record. 1995;45:349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Titchener E. B. A text-book of psychology. New York, NY: MacMillan; 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan M. Rule-governed behavior in behavior analysis: A theoretical and experimental history. In: Hayes S. C, editor. Rule-governed behavior: Cognition contingencies, and instructional control. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan R, Barnes-Holmes D. The transformation of consequential functions in accordance with the relational frames of same and opposite. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2004;82:177–195. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2004.82-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan R, Barnes-Holmes D, Dymond S. The transformation of consequential functions in accordance with the relational frames of more-than and less-than. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2006;86:317–335. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.113-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]