SUMMARY

Patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) often require assistance from family caregivers during the treatment and post-treatment period. This review article sought to summarize current findings regarding the psychological health of HNSCC caregivers, including factors that may be associated with poorer psychological health. Online databases (PUBMED, MEDLINE and PSYCINFO) were searched for papers published in English through September 2010 reporting on the psychological health of caregivers of HNSCC patients. Eleven papers were identified. Caregivers experience poorer psychological health, including higher levels of anxious symptoms, compared to patients and to the general population. Fear of patient cancer recurrence is evident among caregivers and is associated with poorer psychological health outcomes. The 6-month interval following diagnosis is a significant time of stress for caregivers. Greater perceived social support may yield positive benefits for the psychological health of caregivers. To date, there have been relatively few reports on the psychological health of caregivers of HNSCC patients. Well designed, prospective, longitudinal studies are needed to enhance our understanding of how caregiver psychological health may vary over the cancer trajectory and to identify strategies for improving caregiver outcomes.

Keywords: Caregiving, Psychological health, Emotional distress, Anxiety, Depression, Head and neck cancer

Introduction

Over the past year, approximately 52,140 new cases of cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx (which comprise most head and neck squamous cell carcinomas [HNSCCs]) will have been diagnosed in the United States.1 Due to the location of the tumor and subsequent treatment, many of these patients will experience significant functional impairment. Functional deficits might include increased pain, problems with eating and swallowing, dry mouth, and speech impairment, while psychosocial changes can include heightened levels of anxious and depressive symptoms, decreased quality of life (QOL), and fewer social interactions.2–5 Such deficits can occur regardless of treatment success and may persist over many years.3,6,7 As a result, relatives and friends, commonly known as informal or family caregivers, often become an indispensable part of a patient’s support team during the treatment and post-treatment period.8

The emotional challenges of caregiving have been extensively investigated in other medical contexts, such as that of the aged, demented, or those with advanced cancer. This literature indicates that caregivers often report experiencing deficits in psychological health and functioning, which has been defined as encompassing emotional distress and depressive and anxious symptoms.9–11 In addition, prior research suggests that a variety of factors may contribute to caregiver psychological health. Many of these factors are described within the conceptual framework developed by Sherwood and colleagues,12 which proposes that caregiver psychological health outcomes (defined as including emotional distress, depressive symptoms, and anxious symptoms) are affected by both patient disease characteristics (e.g., disease stage, time since diagnosis, patient functioning and needs) and caregiver personal characteristics and resources (e.g., sociodemographic factors, social support). Further, while patient disease characteristics may directly contribute to caregiver psychological health, caregiver characteristics may either directly impact psychological health or moderate the association between disease characteristics and caregiver psychological health.

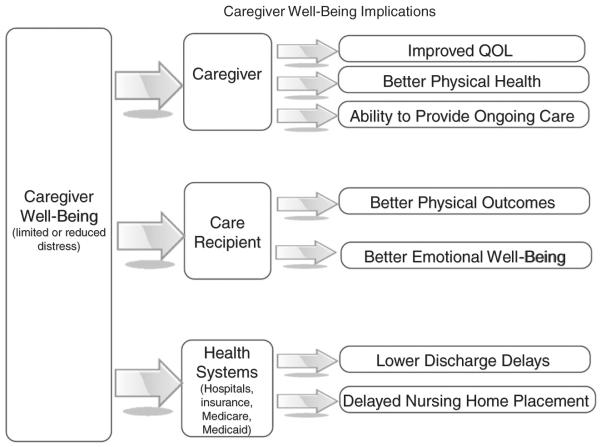

Understanding the psychological health of caregivers, and any contributing factors, is a critical undertaking given that caregiver psychological health has implications for the caregiver’s own quality of life (QOL), physical health, and ability to provide on-going care.13–16 The extant literature (primarily dementia-related) also illustrates that the psychological health of caregivers is associated with patient health outcomes, including patient utilization of health care services.17–21 Specifically, higher levels of caregiver perceived burden (i.e., how “burdened” or encumbered a caregiver feels when taking care of another person) and depressive symptoms have been shown to be directly and indirectly associated with a greater probability of placing a patient in a nursing home.22–26 In contrast, the provision of caregiver interventions, which included elements to address caregiver psychological health, was associated with delays in nursing home placement and reduced mortality among patients.20,27–29 Further, moderate and severe caregiver perceived burden and low quality of life (QOL) were reported to be early predictors of prolonged hospital stays among patients.19

Hence, a greater understanding of the factors that contribute to caregiver psychological health may have important implications not only for improving caregiver outcomes, but also for patient outcomes and the healthcare system (see Fig. 1). Yet, as new and targeted therapies are enabling more patients to live longer with their cancers, relatively little attention has been focused on caregiving within the cancer context, and specifically within the domain of HNSCC, despite the considerable challenges of assisting HNSCC patients. Therefore, the purpose of this review article was to assess prior empirical data regarding the psychological health of HNSCC caregivers. In addition, guided by the conceptual framework described by Sherwood and colleagues,12 we examined whether patient disease characteristics and caregiver personal characteristics and resources were associated with caregiver psychological health. The specific research questions to be addressed include:

What is the psychological health of HNSCC caregivers?

What factors are associated with deficits in psychological health among HNSCC caregivers?

Figure 1.

Implications of caregiver well-being on caregiver outcomes, patient outcomes and healthcare utilization.

Materials and methods

Published articles were identified through a literature search using online databases (PUBMED, MEDLINE and PSYCINFO) for papers published in English through September 2010, which included combinations of the following key words: head and neck cancer; oral cavity cancer; laryngeal cancer; pharynx cancer; caregiving, and caregiver. Reference lists from citations were also reviewed for relevant publications. The aim of the literature review was to identify studies that reported on the psychological health (i.e., emotional distress, depressive or anxious symptoms, and/or perceived burden) of caregivers of HNSCC patients and to identify potential factors associated with deficits in psychological health. Specific article inclusion criteria included: (1) studies of caregivers of patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer; and (2) studies with qualitative or quantitative assessments of caregiver psychological health (i.e., emotional distress, depressive or anxious symptoms, or burden). Papers were excluded if: (1) samples included caregivers of patients with several forms of cancer; or (2) patients were diagnosed with cancers other than HNSCC. The methodological quality of the selected studies was assessed using a 7-item checklist of predefined criteria, which are presented in Table 1. This checklist was adapted from previously published, standardized quality checklists.30–32

Table 1.

Criteria for assessing the methodological and statistical quality of the studies reviewed.

| (A) Sample characteristics: Well characterized patient population with defined inclusion and exclusion criteria |

| (B) Sample Size: The sample size is adequate to assess outcomes or is appropriately justified |

| (C) Data collection: The process of data collection is described (e.g., interviews or self-report) |

| (D) Response rates: Participation and response rates are described and are above 75% |

| (E) Outcome measurement: Standardized measurement of psychological health outcomes |

| (F) Comparison groups: Results are compared between two groups or more (e.g., patients or health populations) |

| (G) Statistical analyses: The statistical analyses are adequately described, including levels of significance and/or confidence intervals when appropriate. A general determination of the extent to which all analyses that should have been done were done |

Note: (Studies were assigned ‘1′ point for each criteria that they met, for a total possible score of 7).

Results

Using the designated search terms, eighteen papers relevant to HNSCC and caregiving were identified for further evaluation. An additional two papers were identified by reviewing citations and reference lists. Three papers were excluded because they focused on patients with esophageal cancer; three were excluded because they did not report HNSCC caregiver psychological health outcomes; one was excluded because the sample included caregivers of patients with other kinds of cancers as well; one was excluded because the primary purpose was to develop standards of care for patients; and one review paper was excluded because its primary focus was on psychosocial care for HNSCC patients (not caregivers). Hence, eleven published papers met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated in detail. Key study details, including measurement tools and the outcomes assessed, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies of HNSCC caregiver psychological well-being.

| First author (year) | Sample | Study design | Measurement tools (measurement outcome) |

Psychological health findings | Methodology and statistical quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ross et al.36 | 89 Caregivers |

Cross-sectional 6– 24 months post-treatment |

CQOLC (quality of life) | • 21.6% Reported moderate emotional distress | 4 |

| (Avg time since diagnosis = 19 months) |

• 15.9% Reported high emotional distress | ||||

| MHI (Global Mental Health; Psychological Distress and Psychological Well-being subscales) |

• 37.5% Reported moderate to high distress on the MHI |

||||

| • Psychological health was negatively associated with hours spent caregiving |

|||||

| FIN (Practical and Informational Needs) |

• Gender, time since family member’s cancer diagnosis, and percentage of unmet needs were not significantly correlated with caregiver psychological health |

||||

| • Greater hours per week were associated with less perceived disruptiveness of caregiving and greater positive adaption to caregiving |

|||||

| Chen et al.34 | 122 Patient- caregiver dyads |

Cross-sectional (immediately post-tumor excision surgery, still hospitalized) |

CRA (perceived caregiver burden) |

• Caregivers had moderate levels of perceived caregiving burden |

6 |

| • Burden was predicted by caregivers’ social support, patients’ physical and daily living needs, patients’ health system and information needs, and patients’ psychological needs |

|||||

| ISSB (Social Support) CNQ-SF (Patient Care Needs) |

|||||

| HNCNQ (Patient Head and Neck Specific Care Needs) |

|||||

| Hodges and Humphris39 |

101 Patient- caregiver dyads |

Longitudinal assessments at 3-and 6-months post patient diagnosis |

HADS (Global Psychological Distress; Depression and Anxiety subscales) |

• At 3-months, 30.7% of caregivers had anxiety symptoms suggestive of clinical anxiety (compared to 18.8% for patients) |

7 |

| • At 6-months, 36.6% of caregivers had anxiety symptoms suggestive of clinical anxiety (20.8% for patients) |

|||||

| WOC (Fear of Recurrence) |

• Caregivers had higher recurrence concerns than patients |

||||

| • Fear of recurrence was correlated with emotional distress at each time point |

|||||

| Roing et al.43 | 7 Spouses | Cross-sectional | Open-ended interview | • Themes identified included: (1) Transitioning from spouse to supportive caregiver; (2) Negligence of self and emotional strain; (3) Restricted living (i.e., holidays); and (4) Altered sense of time (e.g., time moving fast or slow) |

2 |

| Baghi et al.42 | 78 Caregivers |

Cross-sectional (median time since treatment = 24 months |

Study specific questionnaire on QOL and personal and support needs of caregiver |

• 43% of caregivers reported needing psychological care for themselves |

3 |

| • 43% also expressed a desire to be in contact with self-help groups |

|||||

| • Caregiver gender (female) was associated with need for psychological support |

|||||

| • Marital status (being married) was associated with use of self-help groups |

|||||

| • Higher education was associated with greater desire for greater psychosocial support |

|||||

| Verdonck-de Leeuw et al.35 |

41 Patient- spouse pairs |

Cross-sectional (mean time since treatment = 29 months) |

HADS (Global Psychological Distress; Depression and Anxiety subscales) |

• Clinical levels of emotional distress were identified in 20% of spouses |

6 |

| • Spouse distress was associated with disrupted schedule, vitality, passive coping style, and patient use of feeding tube |

|||||

| SF-36 (Health Status) | • Emotional distress was not associated with tumor site, time interval since treatment or treatment type |

||||

| • Emotional distress was significantly related to CRA Disrupted Schedule subscale |

|||||

| ACE-27 (Patient Health Status) |

|||||

| UCL (Coping Style) EORTC |

|||||

| QLQ-H&N35 (Patient Social and Functional Impairment) |

|||||

| CRA (Perceived Caregiver Burden) |

|||||

| Ostroff et al.38 | 80 Patient- caregiver dyads |

Cross-sectional (completed treatment within prior 6– 24 months) |

MHI (Global Mental Health; Psycholog |

• Caregivers reported poorer psychological health than population norms |

6 |

| Distress and Psychological Well-being subscales) |

|||||

| PAIS-SR (Psychological Adjustment to Illness) |

|||||

| FAD (Family Functioning) |

|||||

| FACT-HN (Cancer- specific QOL) |

|||||

| Vickery et al.37 | 44 Partners (and 51 patients) |

Cross-sectional assessment conducted post-treatment (mean time since treatment = 11 months) |

HADS (Global Mental Health; Psychological Distress and Psychological Well-being subscales) |

• Median anxiety scores for partners were suggestive of borderline clinical anxiety |

6 |

| PAIS-SR (Psychological Adjustment to Illness |

• 40% of partners had symptoms suggestive of clinical or borderline levels of anxiety |

||||

| DAS (Quality of Spousal Relationship) |

|||||

| Watt-Watson and Graydon5 |

18 Patients and their caregivers |

Longitudinal (immediately before patient discharge and 4-weeks postdischarge) |

Open-ended interview | • Patients and caregivers expressed fears of recurrence |

3 |

| Blood et al.33 | 75 Spouse caregivers |

Cross-sectional (time since surgery ranged from 2 to 48 months) |

CSI (Caregiver burden and strain) |

• Caregivers at 2–6 months post-diagnosis had higher mean caregiver stress than caregivers farther from diagnosis |

5 |

| BI (Perceived Burden) GARS (Current Stress Levels) |

|||||

| HS-MOS (Health Status) | |||||

| Mah and Johnston44 | 4 Families | Longitudinal (before treatment, during treatment, and during rehabilitation) over a period of 5-months |

Semi-structured interview and chart reviews |

• Five major types of concerns were revealed: cancer and its meaning; social relations; experience with hospitalization; treatment; and, future care placement |

2 |

| • At pretreatment, families focused on treatment implications |

|||||

| • During treatment, families focused on social relations |

|||||

| • During rehabilitation, older family caregivers focused on future care placement |

Note: Abbreviations used include: ACE-27: Adult Co-morbidity Evaluation 27; BI: Burden Interview; CNQ-SF: Cancer Needs Questionnaire Short Form; CQOLC: Caregiver Quality of Life Index; CRA: Caregiver Reaction Assessment; CSI: Caregiver Strain Index; DAS: Dyadic Adjustment Scale; EORTC QLQ-H&N35: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Head and Neck Module; FACT-HN: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head and Neck; FAD: Family Assessment Device; FIN: Family Inventory of Needs; GARS: Global Assessment of Recent Stress; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale; HNCNQ: Head and Neck Specific Cancer Needs Questionnaire; HS-MOS: Health Survey of the Medical Outcomes Study-short form; ISSB: Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors; MHI: Mental Health Inventory; PAIS-SR: Psychological Adjustment to Illness Scale-SR; UCL: Utrecht Coping List; WOC: Worry of Cancer.

Question #1: What is the psychological health of HNSCC caregivers?

The caregiver psychological health outcomes most commonly assessed were emotional distress, anxious or depressive symptoms, and caregiver perceived burden. In the literature reviewed, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Mental Health Inventory (MHI) were the most frequently used tools to assess overall levels of emotional distress and specific levels of anxious symptoms (e.g., high levels of physiological hyperarousal) and depressive symptoms (e.g., low levels of positive affect). Perceived burden was primarily assessed using either the Zarit Burden Interview (BI), which assesses how “burdened” or overwhelmed caregivers felt with respect to caregiver behaviors; or the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA), which explores how caregiving may have impacted financial issues, health problems, family relations, and disrupted schedules. Burden has been studied both as a psychological outcome of caregiving33,34 and also as a correlate of emotional distress.35 Similar to burden, some studies utilized a standardized assessment of caregiver “strain” (i.e., Caregiver Strain Index), which measures how caregiving has adversely impacted the life of a caregiver (e.g., disrupted sleep).

Studies suggest that a fairly large proportion of HNSCC caregivers experience emotional distress (20% based on the HADS total score or 38% using the MHI).35,36 Caregivers were also more likely to experience poorer psychological health (i.e., higher levels of emotional distress, more anxious symptoms) compared to population norms37,38 and compared to HNSCC patients themselves.37,39 For example, in a study of patients and their partners,37 partners of patients who received surgery along with radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or chemotherapy (S/R/B/C) and partners of patients who received radiotherapy/brachytherapy only (R/B) had more symptoms of anxiety than the general population (3–6%).40 In fact, 40% of the S/R/B/C group and 16% of the R/B group reported elevated levels of anxious symptoms that were above the reported cutoffs suggestive of clinical anxiety disorders. Indeed, median anxiety symptom scores for partners in both groups fell within the range of borderline clinical cases, whereas median scores for patients were within the normal range.37 Although partners had more symptoms of anxiety than patients, they did not report high levels of depressive symptoms, which were within the normal range37,39 and were fairly equivalent to rates observed in the general population (10–12%).41 Studies have also found that 43% of caregivers reported needing psychological care for themselves42 and expressed heightened levels of caregiving strain and burden.33–35

Question #2: What factors are associated with deficits in psychological health among HNSCC caregivers?

The following section summarizes key factors reported to be associated with poorer psychological health among HNSCC caregivers.

Caregiver sociodemographic factors

In the majority of studies identified in this review, caregivers were predominantly female and the spouse of the patient. Further, the mean age of caregivers was in the mid-to-late fifties. Several studies investigated whether key demographic variables were associated with psychological functioning. In an early study33 assessing caregiver strain and perceived burden among 75 spouses of patients who had undergone laryngectomy, male spouses reported less strain and burden compared with female spouses. However, the number of male spouses in the study was relatively small as most caregivers were female (80%).33 A significant relationship between gender and expressed need for psychological support was observed in one study, with more women than men considering support necessary.42 However, other studies35,36 have reported that caregiver gender is not significantly associated with psychological health.

Mixed results were also found with regard to education level. Baghi et al.42 reported that caregivers with higher education levels considered it necessary to have psychological support (for themselves and for the patient) and sought more contact with self-help groups, whereas Ross et al.36 found no significant association between caregiver education and quality of life or psychological health. In one study, marital status was significantly associated with use of self-help groups (i.e., married couples considered such support necessary).42 Caregiver age was not significantly associated with psychological health or quality of life.35,36

Time since patient diagnosis

Some studies have reported that the time frame following diagnosis and during treatment is an extremely stressful period, with caregivers at 2–6 months post-diagnosis reporting higher levels of perceived burden and strain compared to caregivers farther out from diagnosis. Perceived burden decreased as time from diagnosis increased.33 At 6–24 months post-treatment, time since diagnosis was no longer significantly associated with caregiver psychological health.36

Hours of care

Greater number of caregiving hours was associated with poorer caregiver psychological health during the 6–24-month post-treatment period. Although caregivers perceived that a greater number of hours spent in caregiving per week was associated with less disruptiveness of caregiving, such hours also had adverse effects on psychological health.36 Perhaps caregivers who spend more hours in the caregiving role are likely to have developed a regular schedule for tending to and incorporating their caregiving responsibilities into their daily routine, but this is done at the expense of their own psychological health.

Lifestyle modifications

Several qualitative studies revealed how aspects of HNSCC caregiving can lead to lifestyle changes. For example, interviews with seven spouses of oral cancer patients identified several themes that may play important roles in the caregiving experience.43 They include: (1) the transition from spouse to supportive caregiver; (2) self-neglect and managing emotional distress; (3) changes in lifestyle and restricted living (e.g., planning schedules around treatment); and (4) an altered sense of time (e.g., time passing quickly or slowly). An additional qualitative analysis5 echoed similar themes as caregivers expressed concerns about not being able “to look after myself and keep myself together” nor “to get time to myself”. Other themes identified in qualitative analyses highlight caregiver apprehension and concerns regarding disruptions in patient socializing (“encouraging patient not to hide”)5 and concerns about social interactions during treatment.44 During the patient’s rehabilitation, families (and particularly older caregivers) expressed concerns regarding the ability to provide ongoing care and the subsequent need for placement at a long-term care facility.44 How well caregivers manage or cope with these diverse issues likely contributes to their psychological health. Indeed, one study reported that caregivers who perceived greater disruptions to one’s lifestyle and schedule had higher levels of emotional distress.35

Patient needs and treatment-related factors

Patient needs were also associated with deficits in psychological health among HNSCC caregivers. In a study of Taiwanese caregivers, levels of perceived caregiving burden were positively associated with the level of patient physical and daily living needs during the time period following tumor resection.34 Caregiver burden was also heightened when patients had greater psychological and informational needs, although perceived support from friends, family members, and health care providers served to attenuate caregiver burden.34

Among 41 patient-spouse pairs, higher levels of spousal emotional distress were related to patient use of a feeding tube and to lower levels of patient energy.35 However, spouse emotional distress was not associated with tumor site, passage of time since treatment, or type of treatment itself.35 And no association was reported between spouse distress and patient self-rated functional impairment.35 Hence, these findings suggest that factors other than patient impairment may play key roles in contributing to caregiver psychological health outcomes.

Cancer recurrence

Although not extensively studied to date, a few studies have observed that caregivers report high levels of fear that the patient’s cancer will recur,5 sometimes at greater levels than the patients themselves.39 Fear of recurrence has been positively associated with emotional distress among caregivers at 3-and 6-months post-diagnosis.39

Discussion

To date, a relatively small number of studies have focused on the psychological health of caregivers of HNSCC patients. In general, these studies have observed that caregivers experience poor psychological health, including elevated levels of emotional distress and anxious symptoms, relative to patients and the general population. Caregivers also report considerable perceived burden and caregiving-related strain. Consistent with Sherwood’s conceptual framework, the literature suggests that various disease characteristics and caregiver personal characteristics are associated with caregiver psychological health outcomes. As noted in Table 2, the methodological and statistical strengths of the available studies varied. Below we discuss some key methodological and conceptual gaps within each domain, and how these considerations may be particularly relevant within the context of caring for patients with HNSCC.

Patient disease characteristics

With few exceptions, the published papers have assessed caregivers of patients with varied disease characteristics (e.g., cancer site, stage, treatment regimen and length of time since diagnosis). Only one study had a relatively homogeneous HNSCC caregiver sample in terms of diagnosis.33 Treatment regimen was often not described or it varied considerably among the patients in each study. Three studies specifically assessed treatment impact on caregiver outcomes,5,35,37 with two involving comparisons across treatment type.35,37 Since caregiving tasks and experiences may vary extensively by treatment modality,5,45 questions remain regarding whether specific treatment-related factors impact caregiver psychological health. Similarly, due to the lack of longitudinal studies, we currently have a limited understanding of caregiver psychological health across the cancer trajectory. However, it appears that the 6-month interval following diagnosis is a time of significant emotional distress among caregivers, coinciding with the greatest demands in managing treatment and treatment-related side effects.

Differences with regard to patient functional impairment could have also influenced caregiving tasks, and subsequently, caregiver psychological health. Consistent with research on women providing care to disabled spouses,10 a greater number of hours spent providing care was associated with poorer psychological health.35,36 However, caregiver psychological health was not reliably associated with patient-rated functional impairment.35 The correspondence between patient self-ratings of functional impairment and objective ratings (or caregiver-ratings) of impairment is unknown; it is possible that caregivers’ assessments would differ from patients’ own self-assessment, which could then differentially influence caregiver emotional distress.46

Future studies will also benefit from evaluating additional patient disease characteristics that are particularly relevant to this population. This might include an understanding of the presence of addictive behaviors among patients and how such factors affect caregiver psychological health during illness and treatment. Indeed, one study reported that nearly 27% of the caregivers indicated that they were “suffering” from the alcohol abuse of the patient.42 Moreover, compared with other cancer patients, HNSCC patients experience one of the highest rates of major depressive disorder.47 However, despite the prevalence of psychiatric issues and nicotine or alcohol dependence in this patient population, the impact of such factors on caregivers of HNSCC patients has not been widely reported. This may be due, in part, to the challenges associated with recruiting patients with addictive disorders into such studies.48 There is likely to be systematic under-reporting of emotional distress if the most distressed patient-caregiver pairs are also the least likely to enroll in these studies. Thus, levels of emotional distress among caregivers are likely higher than what is currently reported in the literature. Further, given differences in the etiology and biology of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related HNSCC, caregiver psychological health outcomes might differ depending upon disease pathology and prognosis.

Caregiver personal characteristics

Previous studies have suggested that female caregivers report poorer psychological health outcomes than male caregivers,49 but findings from the present review regarding gender and psychological health were mixed. This may be due to the limited number of male caregivers studied. Educational level was also not associated with emotional distress in this caregiving population,36 although it may be an important factor predicting who will seek services or resources for mental health concerns. More educated caregivers recognized the need for support and were more aware of psychological services that were available to them. Therefore, future programs might focus on increasing awareness of available services for those subgroups of caregivers who lack this information.

Importantly, we noted that the conceptualization of “caregiver” varied widely across studies, with some studies assessing only spouses/partners (assumed to be the primary caregivers),37 some including the term “primary caregiver” in recruitment,34 and others not assessing whether the survey respondent was the primary caregiver.36 The inclusion of caregivers with varied roles and responsibilities (e.g., primary vs. secondary caregiver) is likely to lead to considerable variations in outcomes. More lenient definitions may result in studies including individuals who do not provide substantial (or any) care; as a consequence, this could lead to significant variations in the level of emotional distress experienced. Thus, moving forward, there is a clear need to rigorously assess well-defined groups of caregivers.

As the demographic characteristics of the HNSCC patient are evolving in view of the increasing number of HNSCCs attributed to HPV, future research will also need to identify whether other caregiver characteristics are reliably associated with psychological health outcomes. Specifically, patients with HPV-related disease tend to be younger at diagnosis. These changing demographics may impact how caregiving is managed and by whom, particularly if the spouse (who has traditionally been the primary caregiver) has greater family responsibilities (e.g., young children residing in the home) and is more likely to be employed full-time rather than retired. As a result of this trend, perhaps the primary caregiving role may no longer be fulfilled predominantly by the spouse; indeed, caregiving responsibilities may need to be shared by a group of relatives (e.g., parents, siblings, and spouse). How family dynamics and other household factors may impact caregiving and affect psychological health outcomes remains understudied.

Qualitative studies have been useful in identifying additional caregiver-related variables, such as fear of recurrence and the impact or burden of caregiving on one’s life. Research findings from other caregiving contexts, such as care of the demented, show that greater perceived burden is associated with poorer psychological health10,11,50 Although spouses noted concern over caregiving-related lifestyle changes (e.g., disruptions in one’s daily schedule, changes in lifestyle, or transitioning in family role from spouse to caregiver), only one study evaluated aspects of burden and psychological health using standardized measures. In this lone study, greater perceived disruption in one’s schedule was associated with poorer psychological health among caregivers.33

Fear of cancer recurrence is a prominent concern for many cancer patients, including HNSCC patients, and results in heightened distress.51,52 It is important to note that HNSCC caregivers also fear a recurrence of cancer, and these levels of fear are sometimes greater than that experienced by the patients themselves. A caregiver’s fear of cancer recurrence was also associated with elevated emotional distress. This is a unique finding compared to other caregiving fields in which fear of recurrence has not been commonly studied (e.g., dementia care; chronic conditions) and suggests that a greater recognition of caregivers’ fears is needed to inform the development of appropriate programs and resources for addressing such fears and concerns among cancer caregivers.

Further, although reports are limited, it appears that perceived support from a network of family members, friends, and/or health care professionals can offer positive benefits for psychological health. Some caregivers reported that self-help groups provided useful services. Similarly, both patients and caregivers reported a desire for support groups to be incorporated within the standard of care for patients in the United Kingdom.53 As a result, enhancing access to support services appears to be a critical need in this understudied population. Ultimately, the development of evidence-based interventions to enhance family caregivers’ psychological health may benefit not only the caregiver, but also the patients who depend on them for care.

Conclusions

In sum, the literature on caregivers of HNSCC patients is relatively limited but is beginning to identify key factors that may be associated with caregiver emotional distress. These findings will be useful in guiding the future development of appropriate interventions designed to reduce distress, enhance psychological functioning, and improve quality of life among family caregivers. In light of research suggesting that caregiver psychological health may have broad implications not only for caregivers,13,15,54 but also for patients13–18,20,55 and the healthcare system,17,19,20 future research would benefit from including a comprehensive assessment of caregiver and patient outcomes and health care utilization.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant P30CA006927.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement None declared.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures 2011. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy BA, Ridner S, Wells N, Dietrich M. Quality of life research in head and neck cancer: a review of the current state of the science. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62(3):251–67. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronis DL, Duffy SA, Fowler KE, Khan MJ, Terrell JE. Changes in quality of life over 1 year in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(3):241–8. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Hammerlid E, et al. A prospective study of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Part II: Longitudinal data. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(8):1440–52. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watt-Watson J, Graydon J. Impact of surgery on head and neck cancer patients and their caregivers. Nurs Clin North Am. 1995;30(4):659–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oates JE, Clark JR, Read J, et al. Prospective evaluation of quality of life and nutrition before and after treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(6):533–40. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.6.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehanna HM, Morton RP. Deterioration in quality-of-life of late (10-year) survivors of head and neck cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31(3):204–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kagan SH, Clarke SP, Happ MB. Head and neck cancer patient and family member interest in and use of E-mail to communicate with clinicians. Head Neck. 2005;27(11):976–81. doi: 10.1002/hed.20263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanderwerker LC, Laff RE, Kadan-Lottick NS, McColl S, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use among caregivers of advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):6899–907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannuscio CC, Jones C, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Berkman L, Rimm E. Reverberations of family illness: a longitudinal assessment of informal caregiving and mental health status in the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1305–11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapari M, Addington-Hall J, Hotopf M. Risk factors for common mental disorder in caregiving and bereavement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(6):844–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherwood PR, Given BA, Donovan H, et al. Guiding research in family care: a new approach to oncology caregiving. Psychooncology. 2008;17(10):986–96. doi: 10.1002/pon.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, Burton L, Hirsch C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: the caregiver health effects study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(2):110–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas P, Lalloue F, Preux PM, et al. Dementia patients caregivers quality of life: the PIXEL study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(1):50–6. doi: 10.1002/gps.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitaliano PP, Scanlan JM, Zhang J, Savage MV, Hirsch IB, Siegler IC. A path model of chronic stress, the metabolic syndrome, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):418–35. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams VP, Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Lane JD, et al. Video-based coping skills to reduce health risk and improve psychological and physical well-being in Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(9):897–904. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181fc2d09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodaty H, Gresham M, Luscombe G. The Prince Henry Hospital dementia caregivers’ training programme. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12(2):183–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199702)12:2<183::aid-gps584>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brodaty H, Mittelman M, Gibson L, Seeher K, Burns A. The effects of counseling spouse caregivers of people with Alzheimer disease taking donepezil and of country of residence on rates of admission to nursing homes and mortality. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(9):734–43. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181a65187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang PO, Zekry D, Michel JP, et al. Early markers of prolonged hospital stay in demented inpatients: a multicentre and prospective study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(2):141–7. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0182-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, Levin B. A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276(21):1725–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, et al. Caregiver-assisted coping skills training for lung cancer: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;41(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruchno RA, Michaels JE, Potashnik SL. Predictors of institutionalization among Alzheimer disease victims with caregiving spouses. J Gerontol. 1990;45(6):S259–266. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.s259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hebert R, Dubois MF, Wolfson C, Chambers L, Cohen C. Factors associated with long-term institutionalization of older people with dementia: data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(11):M693–699. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.11.m693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coehlo DP, Hooker K, Bowman S. Institutional placement of persons with dementia: what predicts occurrence and timing? J Fam Nurs. 2007;13(2):253–77. doi: 10.1177/1074840707300947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kesselring A, Krulik T, Bichsel M, Minder C, Beck JC, Stuck AE. Emotional and physical demands on caregivers in home care to the elderly in Switzerland and their relationship to nursing home admission. Eur J Public Health. 2001;11(3):267–73. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brodaty H, McGilchrist C, Harris L, Peters KE. Time until institutionalization and death in patients with dementia. Role of caregiver training and risk factors. Arch Neurol. 1993;50(6):643–50. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540060073021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Steinberg G, et al. An intervention that delays institutionalization of Alzheimer’s disease patients: treatment of spouse-caregivers. Gerontologist. 1993;33(6):730–40. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, Roth DL. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242727.81172.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(17):2613–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ropka ME, Wenzel J, Phillips EK, Siadaty M, Philbrick JT. Uptake rates for breast cancer genetic testing: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(5):840–55. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West S, King V, Carey TS, et al. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2002;47:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blood GW, Simpson KC, Dineen M, Kauffman SM, Raimondi SC. Spouses of individuals with laryngeal cancer: caregiver strain and burden. J Commun Disord. 1994;27(1):19–35. doi: 10.1016/0021-9924(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen SC, Tsai MC, Liu CL, Yu WP, Liao CT, Chang JT. Support needs of patients with oral cancer and burden to their family caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(6):473–81. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b14e94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Eerenstein SE, Van der Linden MH, Kuik DJ, de Bree R, Leemans CR. Distress in spouses and patients after treatment for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):238–41. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000250169.10241.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross S, Mosher CE, Ronis-Tobin V, Hermele S, Ostroff JS. Psychosocial adjustment of family caregivers of head and neck cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(2):171–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0641-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vickery LE, Latchford G, Hewison J, Bellew M, Feber T. The impact of head and neck cancer and facial disfigurement on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Head Neck. 2003;25(4):289–96. doi: 10.1002/hed.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostroff J, Ross S, Steinglass P, Ronis-Tobin V, Singh B. Interest in and barriers to participation in multiple family groups among head and neck cancer survivors and their primary family caregivers. Fam Process. 2004;43(2):195–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04302005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hodges LJ, Humphris GM. Fear of recurrence and psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients and their carers. Psychooncology. 2009;18(8):841–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clarke DM. Anxiety states: panic and generalised anxiety. In: Hawton K, Salkoskis PM, Kirk J, Clarke DM, editors. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric problems: a practical guide. Oxford Medical Publications; 1995. pp. 52–96. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fennell M. Depression. In: Hawton K, Salkoskis PM, Kirk J, Clarke DM, editors. Cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric problems: a practical guide. Oxford Medical Publications; 1995. pp. 169–234. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baghi M, Wagenblast J, Hambek M, et al. Demands on caring relatives of head and neck cancer patients. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(4):712–6. doi: 10.1097/mlg.0b013e318031d0b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roing M, Hirsch JM, Holmstrom I. Living in a state of suspension – a phenomenological approach to the spouse’s experience of oral cancer. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(1):40–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mah MA, Johnston C. Concerns of families in which one member has head and neck cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1993;16(5):382–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Penner JL. Psychosocial care of patients with head and neck cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25(3):231–41. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clipp EC, George LK. Patients with cancer and their spouse caregivers. Perceptions of the illness experience. Cancer. 1992;69(4):1074–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920215)69:4<1074::aid-cncr2820690440>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lydiatt WM, Moran J, Burke WJ. A review of depression in the head and neck cancer patient. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009;7(6):397–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duffy SA, Scheumann AL, Fowler KE, Darling-Fisher C, Terrell JE. Perceived difficulty quitting predicts enrollment in a smoking-cessation program for patients with head and neck cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(3):349–56. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.349-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yee JL, Schulz R. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40(2):147–64. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. CMAJ. 2004;170(12):1795–801. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adams E, McCann L, Armes J, et al. The experiences, needs and concerns of younger women with breast cancer: a meta-ethnography. Psychooncology. 2011;20(8):851–61. doi: 10.1002/pon.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers SN, Scott B, Lowe D, Ozakinci G, Humphris GM. Fear of recurrence following head and neck cancer in the outpatient clinic. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267(12):1943–9. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1307-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richardson A, Lee L, Birchall M. Learning from patients with cancer and their spouses: a focus group study. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116(12):1028–35. doi: 10.1258/002221502761698784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vitaliano PP, Young HM, Zhang J. Is caregiving a risk factor for illness? Am Psychologic Soc. 2004;13(1):13–6. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang ST, Liu TW, Tsai CM, Wang CH, Chang GC, Liu LN. Patient awareness of prognosis, patient-family caregiver congruence on the preferred place of death, and caregiving burden of families contribute to the quality of life for terminally ill cancer patients in Taiwan. Psychooncology. 2008;17(12):1202–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]