Abstract

Objective:

Recent reports indicate an increase in rates of hospitalizations for drug overdoses in the United States. The role of alcohol in hospitalizations for drug overdoses remains unclear. Excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs is prevalent in young adults ages 18–24. The present study explores rates and costs of inpatient hospital stays for alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their co-occurrence in young adults ages 18–24 and changes in these rates between 1999 and 2008.

Method:

Data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample were used to estimate numbers, rates, and costs of inpatient hospital stays stemming from alcohol overdoses (and their subcategories, alcohol poisonings and excessive consumption of alcohol), drug overdoses (and their subcategories, drug poisonings and nondependent abuse of drugs), and their co-occurrence in 18- to 24-year-olds.

Results:

Hospitalization rates for alcohol overdoses alone increased 25% from 1999 to 2008, reaching 29,412 cases in 2008 at a cost of $266 million. Hospitalization rates for drug overdoses alone increased 55%, totaling 113,907 cases in 2008 at a cost of $737 million. Hospitalization rates for combined alcohol and drug overdoses increased 76%, with 29,202 cases in 2008 at a cost of $198 million.

Conclusions:

Rates of hospitalizations for alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their combination all increased from 1999 to 2008 among 18- to 24-year-olds. The cost of such hospitalizations now exceeds $1.2 billion annually. The steepest increase occurred among cases of combined alcohol and drug overdoses. Stronger efforts are needed to educate medical practitioners and the public about the risk of overdoses, particularly when alcohol is combined with other drugs.

In the united states, approximately 61% of the population ages 18 and older consumes alcohol at least once per year (Schoenborn and Adams, 2010). The vast majority of drinkers (92%) consume alcohol at or below moderate levels (1 drink per day and no more than 7 drinks per week for women or 2 drinks per day and no more than 14 drinks per week for men; Schoenborn and Adams, 2010). Light and moderate drinking can be part of a healthy lifestyle for adults and is associated with cardiovascular benefits and longevity in general (Dawson, 2000; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2005). In contrast, consuming alcohol beyond moderate levels increases the risk of negative outcomes and is a causal factor in more than 60 types of diseases and injuries (World Health Organization [WHO], 2011). The WHO estimates that alcohol causes 2.5 million premature deaths worldwide each year, accounting for 4% of all deaths (6% of all deaths for males and 1% for females) (WHO, 2011). In the United States, excessive consumption of alcohol is estimated to cause approximately 79,000 deaths and 2.3 million years of potential life lost annually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010b).

When consumed in large quantities during a single occasion, alcohol can cause death directly by suppressing brain stem nuclei that control vital reflexes, such as breathing and gagging to clear the airway (Miller and Gold, 1991). Even a single session of heavy episodic drinking, commonly defined as five or more drinks per occasion, causes inflammation and transient damage to the heart (Zagrosek et al., 2010). The acute toxic effects of alcohol in the body can manifest in symptoms of alcohol poisoning, which include vomiting, slow and irregular breathing, hypothermia, mental confusion, stupor, and death (NIAAA, 2007; Oster-Aaland et al., 2009). Using data from the global burden of disease study, the WHO estimated that alcohol poisoning caused 65,700 deaths worldwide in 2002, with 2,700 poisoning deaths occurring in the United States (WHO, 2009).

Excessive consumption of alcohol is particularly common among those 18–24 years of age, a time of transition from late adolescence into young adulthood (National Center for Health Statistics, 2009). Compared with older adults, those ages 18–24 are more likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking and to participate in a range of risky behaviors involving alcohol, including driving while intoxicated (Dayan et al., 2010; Hingson et al., 2009). Approximately 25% of young people in this age group consume five or more drinks in a day at least once per month (National Center for Health Statistics, 2009), and rates are higher (44%) among those attending college (Wechsler and Nelson, 2008). Relative to people in older age groups, young adults ages 18–24 consume the most drinks (M = 9.5) per episode of heavy drinking (Naimi et al., 2010). White et al (2006) reported that, among college freshmen, nearly 1 in 5 (19%) male heavy episodic drinkers consumed 15 or more drinks in a night, a potentially lethal level, at least once in a 2-week period. Hingson et al. (2009) estimated that 609 young adults ages 18–24 died from alcohol poisoning in the United States in 2005 as a result of heavy drinking.

Use of substances other than alcohol also peaks in the late teenage years and early 20s. In 2009, 21% of 18- to 25-year-olds used one or more illicit drugs each month, and 6% used a prescription drug nonmedically (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2010d). Overdose deaths from illicit and prescription drugs have increased steeply in the United States in recent years. In 2007, an estimated 27,658 people ages 15 and older died from drug poisonings, making deaths from drug overdoses second only to deaths from motor vehicle crashes as the leading cause of unintentional injury deaths that year (CDC, 2010a). Rates of deaths from drug overdose more than doubled for males and tripled for females between 1999 and 2007 (CDC, 2010a). Overdoses from prescription opioid pain medications increased the most and outnumbered deaths from heroin and cocaine overdoses combined in 2007 (CDC, 2010a). Based on data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), which contains data pertaining to roughly 8 million inpatient discharges each year from a 20% stratified sample of community hospitals across the country, Coben and colleagues (2010) observed a 65% increase between 1999 and 2006 in hospital stays for poisoning by prescription opioids,sedatives, and tranquilizers.

Alcohol interacts with a wide variety of illicit and prescription drugs, including opioids and related narcotic analgesics, sedatives, and tranquilizers (NIAAA, 1995; Tanaka, 2002). In 2007, data from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) suggested that 26% of all emergency department visits for drug misuse also involved the use of alcohol. Alcohol was involved in 17% of emergency department visits resulting from use of benzodiazepine sedatives and tranquilizers and 14% of visits stemming from use of opioids and related narcotic pain medications (SAMHSA, 2010c). Blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) required for fatal overdoses are lower when alcohol is combined with prescription drugs (Jones et al., 2011). An analysis of 1,006 fatal poisonings because of alcohol alone or in combination with other drugs revealed that the median postmortem BAC in those who overdosed on alcohol alone was 0.33%, compared with 0.13%–0.17% among those who overdosed on a combination of alcohol and prescription drugs (Koski et al., 2003, 2005).

Data from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions indicate that the combined use of alcohol and other drugs peaks in the 18- to 24-year-old age range (McCabe et al., 2006). Given the high levels of alcohol consumption during these years and the combined use of alcohol and other drugs, it is important to examine the overlap in incidences of alcohol overdoses and drug overdoses in 18- to 24-year-olds. It is possible that the increasing rates of hospitalizations and deaths because of drug overdoses reported in previous studies are related to an increase in the excessive use of alcohol along with these other drugs.

The current study examined rates of inpatient hospitalizations for alcohol overdoses, other drug overdoses, and their co-occurrence in 18- to 24-year-olds during the years 1999–2008 using data from the NIS. Overdoses were defined as inpatient discharges indicating alcohol or other drug poisoning, or excessive consumption of alcohol or other drugs. Based on recent reports indicating an increase in drug poisonings in the general population and the high levels of alcohol and other drug use among those ages 18–24, we anticipated that rates of inpatient hospitalizations for alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, their subcategories (poisoning and excessive consumption), and their co-occurrence increased among 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States during the decade spanning 1999–2008. Based on reports that overdoses on opioid pain medications and related narcotic analgesics have increased, we also examined changes in rates of prescription opioid pain medication and related narcotic analgesic overdoses and their co-occurrence with alcohol overdoses.

Method

Data

The current study examined hospitalization data from the NIS, years 1999–2008. The NIS is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It was designed to approximate a 20% sample of U.S. community hospitals as defined by the American Hospital Association. The sampling strata were five hospital characteristics: U.S. region, urban or rural location, teaching status, ownership and control, and bed size. All-payer inpatient stays in the sampled hospitals were included in the NIS, yielding the largest inpatient data set in the United States, containing data on approximately 8 million discharges each year. The number of participating states in the HCUP was 24 in 1999 and increased to 42 in 2008, which covered 65% and 95% of the U.S. population, respectively. With sampling weights, the NIS can be used to estimate national statistics on hospitalizations. Because "state" is not one of the sampling strata, the NIS cannot be used to generate state-level estimates. The unit of the NIS was an individual discharge record.

Case selection

Data of interest pertained to hospitalizations associated with poisoning and nondependent abuse of alcohol and drugs in patients ages 18–24. The NIS uses the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), to code primary and secondary diagnoses of hospitalizations. The database provides up to 15 diagnosis codes and up to 4 external causes of injury and poisoning (E-codes) per record. Cases included in the study were selected by searching all listed diagnosis codes and E-codes. Hospitalizations related to alcohol overdose and drug overdose were sorted into categories operationally defined as follows:

Alcohol overdose

Alcohol poisoning: 980 (toxic effect of alcohol), and/or E860 (accidental poisoning by alcohol, not elsewhereclassified)

Excessive consumption of alcohol: 303.0 (acute alcoholic intoxication), 305.0 (nondependent alcohol abuse), and/or 790.3 (excessive blood alcohol level)

Drug overdose

Drug poisoning: 960–979 (poisoning by drugs, medicinals, and biological substances), E850–E858 (accidental poisoning by drugs, medicinals, and biological substances), E950.0–E950.5 (suicide and self-inflicted poisoning by drugs and medicinals), E962.0 (homicidal poisoning by drugs and medicinal substances), and/or E980.0–E980.5 (poisoning by drugs and medicinals, undetermined whether accidentally or purposely inflicted)

Excessive consumption of drugs: 305.2–305.9 (nondependent abuse of drugs)

Inclusion of a case in the alcohol overdose category and the subgroups alcohol poisoning and excessive consumption of alcohol required the absence of codes for drug poisoning and excessive consumption of drugs. The reverse applied to cases categorized as drug overdoses and the subgroups. As such, estimated rates of alcohol overdoses were mutually exclusive from estimated rates of drug overdoses, except where analyses specifically looked for the co-occurrence of alcohol overdose and drug overdose and their subgroups. Within the alcohol overdose category, if a discharge record contained codes for both alcohol poisoning and excessive consumption of alcohol, it was assigned to alcohol poisoning. If excessive consumption of drugs co-occurred with drug poisoning, it was assigned to drug poisoning.

Hospitalizations for opioids and related narcotics were defined as discharges with any listed diagnosis codes of 305.5 (nondependent abuse of opioid), 965.02 (poisoning by methadone), and 965.09 (poisoning by other opiates and related narcotics) as well as any listed E-codes of E850.1 (accidental poisoning by methadone) and E850.2 (accidental poisoning by other opiates and related narcotics). Codes for opium (965.00) and heroin (965.01) were not included because these narcotics are purely illicit and not prescribed for pain.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SAS-callable SUDAAN 10.0. Weights were provided in the NIS for calculating national estimates and the 95% confidence intervals. The overall and gender-specific rates of hospitalizations were calculated as a weighted number of discharges per 100,000 population ages 18–24 years. The denominators of these rates were annual population estimates for adults ages 18–24 years in the United States from 1999 to 2008 obtained from the data released by the U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division (2001, 2010).

Linear trends in rates of alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, combined alcohol and drug overdoses, and prescription opioid and related narcotics overdoses from 1999 to 2008 were tested using weighted least squares linear regression, in which year was an independent variable and the inverse of the square of standard errors of the rates in each year was used as the weight (Cox et al., 2007; Gillum et al., 1996). Gender and an interaction term between gender and year were added as covariates in a separate model of gender-specific rates to test whether there were differences between genders in terms of averaged hospitalization rates and in terms of linear trend of the rates over the period. Two-sided trend tests were conducted at an a priori α level of .05.

Although the primary focus of this project was young adults ages 18–24, analyses were performed to compare estimated rates of alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their combination in young adults ages 18–24 with adults ages 25 and older. The annual rates for adults ages 25 and older were adjusted to the U.S. 2000 standard population using four age groups (25–34, 35–44, 45–64, and 65 years and older) to control for changes in the population's age distribution over time (Klein and Schoenborn, 2001). The comparison of estimated rates was conducted using weighted least squares linear regression.

The cost of alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their combination was estimated based on hospital charges indicated in discharge records and the cost-to-charge ratios developed by the HCUP. As per HCUP recommendations (HCUP, 2010), modified weights and the following method were used to calculate the national total cost: TOTCHG (amount the hospital charged for the entire hospital stay) × GAPICC (group average all-payer inpatient cost/charge ratio). Estimated costs are reported to the nearest millions.

Results

Alcohol overdoses

The total number of inpatient discharges with diagnostic codes indicating an alcohol overdose with or without other drug involvement increased from 34,745 in 1999 to 58,615 in 2008. Among these, 59% of discharges in 1999 and 50% in 2008 did not have drug overdoses indicated. Results in this section focused on those cases that did not overlap with drug overdoses.

The hospitalization rate for alcohol overdoses increased approximately 25% from 78.42 per 100,000 young adults ages 18–24 in 1999 to 97.75 per 100,000 in 2008 (trend p < .0001; see Figure 1a). Rates of hospitalizations for excessive consumption of alcohol increased significantly from 1999 to 2008 (p = .0001; see Figure 1b), whereas rates of hospitalizations specifically for alcohol poisonings did not increase significantly (p = .12; see Figure 1c). Alcohol poisonings accounted for only 2% of alcohol overdoses in 2008.

Figure 1.

Alcohol overdoses. (a) All alcohol overdoses. Rates of hospitalizations increased among 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States between 1999 and 2008 (25%, trend p < .0001) and were higher in men than in women (p < .001). (b) Subcategory: excessive consumption of alcohol. Rates increased over time (25%, trend p = .001) and were higher in men than in women (p < .001). (c) Subcategory: alcohol poisoning. Rates did not increase significantly overtime (31%, trend p = .12) and were higher for men than for women (p < .001). Alcohol poisonings comprised 2% and excessive consumption of alcohol comprised 98% of alcohol overdoses in 2008.

Overall, men had higher rates of hospitalizations than women for alcohol overdoses and the subgroups alcohol poisoning and excessive consumption of alcohol (p < .001). No interactions between gender and year were observed (p > .05).

In 2008, the cost of hospital stays stemming from alcohol overdoses without other drug involvement was estimated to be $266 million. (All dollar amounts in this article are expressed in U.S. dollars.)

Other drug overdoses

The total number of inpatient discharges with diagnostic codes indicating a drug overdose with or without alcohol involvement increased from 77,676 in 1999 to 143,109 in 2008. Among these, 82% of discharges in 1999 and 80% in 2008 did not have alcohol overdoses indicated. Results in this section focused on those drug overdoses that did not overlap with alcohol overdoses.

The hospitalization rate for drug overdoses increased approximately 55% from 243.47 per 100,000 young adults ages 18–24 years in 1999 to 378.55 per 100,000 in 2008 (trend p < .0001; see Figure 2a). Women had higher rates than men for hospitalization because of drug overdoses (p < .0001), and the rates among women increased over time faster than the rates among men (p < .01).

Figure 2.

Drug overdoses. (a) All drug overdoses. Rates increased among 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States between 1999 and 2008 (55%, trend p < .0001). Rates were higher (p < .0001) and increased faster over time (p < .01) for women than for men. (b) Subcategory: excessive consumption of drugs. Rates increased over time (79%, trend p < .0001). Rates were similar for women and for men (p > .05) but increased faster over time for women (p < .01). (c) Subcategory: drug poisoning. Rates increased over time (19%, trend p < .05) and were higher for women than for men (p < .0001). Drug poisonings comprised 30% and excessive consumption of drugs comprised 70% of all drug overdoses in 2008.

Hospitalizations for the subcategory excessive consumption of drugs increased significantly over time (p < .0001; see Figure 2b). There was no difference between men and women for rates of hospitalizations for excessive consumption of drugs, but an interaction between gender and year indicated a steeper increase in rates of hospitalizations for excessive consumption of drugs for women than for men (p < .01).

Drug poisonings accounted for 30% of drug overdoses, and the rate of drug poisonings increased significantly over time (p < .05; see Figure 2c). Women had higher rates than men for hospitalizations because of drug poisonings (p < .0001).

In 2008, the cost of hospital stays stemming from drug overdoses without alcohol involvement was estimated to be $737 million.

Combined alcohol overdoses and drug overdoses

In 2008, an estimated 29,202 discharges among young adults ages 18–24 indicated combined diagnoses of alcohol overdose and drug overdose (rate of 97.05 per 100,000), representing an increase of 76% in the age-specific rate of combined overdoses from 1999 (55.16 per 100,000; trend p < .0001; see Figure 3a). Analyses revealed higher rates of hospitalizations for combined alcohol and drug overdoses among men than among women (p < .0001) and an interaction between gender and year indicating a steeper increase in rates of combined overdoses for men than for women (p < .05).

Figure 3.

Combined alcohol and drug overdoses. (a) Rates of hospitalizations for combined alcohol and drug overdoses increased among 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States between 1999 and 2008 (76%, trend p < .0001). Overall rates were higher (p < .0001) and increased faster over time (p < .05) for men than for women. (b) Rates of hospitalizations for excessive consumption of both alcohol and drugs increased (80%, trend p < .0001). Overall rates were higher (p < .0001) and increased faster over time (p < .01) for men than for women. (c) Rates of hospitalizations for combined alcohol poisoning and drug poisoning increased (45%, trend p < .05). No gender differences were observed for combined alcohol poisoning and drug poisoning (p > .05).

Analyses revealed that 20.4% of all hospitalizations for drug overdoses in 2008 also involved an alcohol overdose. This reflects a small but significant increase in the overlap between alcohol and drug overdoses since 1999 (18.5%; trend p < .05). In 2008, drug overdose cases were more likely to involve alcohol overdoses for men (25.8%) than for women (15.3%; p < .0001).

With regard to the co-occurrence of specific subgroups of alcohol overdoses and drug overdoses, rates of hospitalizations reflecting excessive consumption of both alcohol and other drugs increased from 38.09 per 100,000 in 1999 to 68.45 per 100,000 in 2008 (trend p < .0001; see Figure 3b). Rates among men were higher (p < .0001) and increased faster (p < .01) than those among women. The estimated number of inpatient discharges with combined diagnoses of alcohol poisoning and drug poisoning increased from 6.30 per 100,000 in 1999 to 9.11 per 100,000 in 2008 (trend p < .05; see Figure 3c). No gender difference and no Year × Gender interaction were observed (p > .05).

In 2008, the cost of hospital stays stemming from combined alcohol overdoses and drug overdoses was estimated to be $198 million, bringing the total estimated annual cost of alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their combination among 18- to 24-year-olds to $1.2 billion.

Role of alcohol overdose in overdoses on prescription opioid pain medications and related narcotic analgesics

For young people ages 18–24, rates of hospitalization because of drug overdoses on prescription opioid pain medications (e.g., oxycodone/acetaminophen [Percocet], hydrocodone/acetaminophen [Vicodin], and oxycodone [Oxycontin]) and related prescription narcotic analgesics (e.g., codeine, meperidine [Demerol], and morphine) increased 122% between 1999 (rate = 21.44 per 100,000) and 2008 (rate = 47.68 per 100,000; p < .0001). No differences between genders or Year × Gender interaction were observed (p > .05; see Figure 4a).

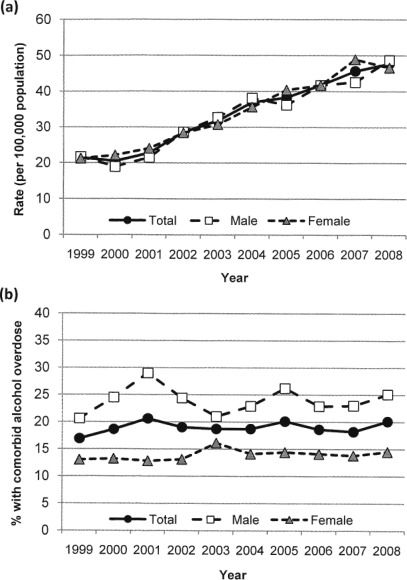

Figure 4.

Role of alcohol in overdoses on opioid pain medications. (a) Rates of hospitalizations for overdoses (poisonings and excessive consumption) on opioid pain medications and related narcotics increased 122% between 1999 and 2008 (trend p < .0001). No gender differences were noted (p > .05). (b) Alcohol overdoses were involved in approximately 20% of overdoses on opioids and related narcotics. Men were more likely than women to be hospitalized for the co-occurrence of an overdose on opioids and alcohol (p < .0001). Overall, the percentage of overdoses on opioids and related narcotics in which an alcohol overdose co-occurred did not change over the years (trend p > .05).

Alcohol overdose was present in 20% of overdoses on opioids and related narcotics (25% for men and 15% for women) in 2008, and this percentage did not increase significantly from 1999 (17%; trend p > .05). Men were more likely than women to be hospitalized for the co-occurrence of an overdose on opioids and related prescription narcotics and an overdose on alcohol (p < .0001; see Figure 4b).

Alcohol and drug overdoses in 18- to 24-year-olds compared with adults ages 25 and older

As with overdoses in those ages 18–24, overdoses on alcohol, other drugs, and the combination of alcohol and other drugs increased among adults ages 25 and older between 1999 and 2008. Overdoses on alcohol among those ages 25 and older increased 23% (from 221.49 to 272.98 per 100,000), overdoses on other drugs increased 57% (from 230.02 to 360.50 per 100,000), and combined overdoses on alcohol and other drugs increased 57% (from 62.30 to 97.72 per 100,000; trend p < .001) (Figure 5a–5c).

Figure 5.

Overdoses in 18- to 24-year-olds compared with adults ages 25 and older. (a) Overall rates of alcohol overdoses were higher (p < .0001) and increased more steeply over time (p < .001) among subjects ages 25 and older than those 18–24 from 1999 to 2008. (b) Overall rates of drug overdoses were higher in those 18–24 than in those 25 or older (p < .025). (c) Overall rates of combined alcohol and drug overdoses were higher in those ages 25 and older than in those ages 18–24 (p < .05).

Overall, rates of alcohol overdoses were higher among adults ages 25 and older than among those ages 18–24 (p < .0001), and an Age Group × Year interaction indicated a faster increase in rates of alcohol overdoses among those 25 and older than those 18–24 (p < .001; Figure 5a). Rates of drug overdoses were higher among young adults ages 18–24 than adults 25 and older (p < .025), whereas rates of combined alcohol overdoses and drug overdoses were higher among those 25 and older (p < .05; Figures 5b and 5c).

Discussion

Results from the NIS revealed an increase in alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their combination in young adults ages 18–24 from 1999 to 2008 in the United States. For alcohol, the increase was primarily because of an increase in cases involving excessive consumption, which comprises the vast majority (98%) of all alcohol overdoses. No significant rise in alcohol poisonings, which comprises only 2% of all alcohol overdoses, was observed. When no other drugs were involved, men were more likely than women to be hospitalized for alcohol overdoses and the two subcategories, alcohol poisoning and excessive consumption of alcohol. This is in line with previous research indicating that college-age men drink more heavily than college-age women (Wechsler and Nelson, 2008; White et al., 2006) and data from DAWN indicating that 59% of alcohol-related emergency department visits for patients ages 12–20 in 2008 involved males (SAMHSA, 2010a). Additional studies report higher rates of mortality from alcohol poisoning in men than women (Yoon et al., 2003). Indeed, the WHO estimates that of the 67,000 deaths resulting from alcohol poisoning worldwide in 2004, deaths among men outnumbered deaths among women by a ratio of 4 to 1 (WHO, 2011).

Increasing rates of hospitalization for alcohol overdoses occurred against the backdrop of decreasing rates of alcohol use by high school students and relatively stable levels of heavy episodic drinking and drinking to drunkenness by those 1–4 years beyond high school, including those in college (Johnston et al., 2010; SAMHSA, 2010d). Research suggests that the risk of alcohol-related injuries is best predicted by drinking levels preceding the injury rather than drinking patterns per se (Cherpitel and Ye, 2009). As such, it is possible that the increased rate of hospitalizations for alcohol overdoses is tied to an increase in punctuated events of overconsumption despite stable or declining drinking levels in the population ages 18–24 as a whole. For instance, it is known that hospitalizations for alcohol overdoses and alcohol-related injuries increase on and around holidays such as New Year's Day. Data from DAWN indicate that an estimated 1,980 underage drinkers were treated at emergency departments for overconsumption and alcohol-related injuries on New Year's Day in 2009, compared with an average of 546 visits on nonholidays throughout the year (SAMHSA, 2010b).

It is possible that young people have become increasingly likely to call for help in cases of alcohol overdose, thereby increasing the number of cases of alcohol overdoses treated at hospitals. In a study of 306 college students surveyed the week before they turned 21, Oster-Aaland et al. (2009) reported that students are able to recognize the symptoms of alcohol poisoning. However, of those who helped a friend suffering from alcohol poisoning, 58% did not seek outside assistance and only 7.5% sought help from a hospital, clinic, or emergency department. In an effort to increase the likelihood that students suffering from alcohol poisoning receive proper care, many colleges and universities have implemented amnesty policies that eliminate or reduce consequences for students who seek medical attention for an intoxicated peer. After Cornell University implemented an amnesty policy and a judicially mandated alcohol poisoning education program for those who required medical treatment following an alcohol overdose, they witnessed an increase in calls to residence assistants and 911 for help dealing with an intoxicated friend (Lewis and Marchell, 2006). As such, the increase in rates of hospitalization for alcohol overdoses could be explained in part by an increase in the likelihood that a young adult will receive treatment for the overdose, rather than simply an increase in the rate of such overdoses per se.

Rates of hospitalizations for drug overdoses, including both poisonings and excessive consumption of drugs, increased from 1999 to 2008. The increase in hospitalizations for drug overdoses occurred against the backdrop of small increases in levels of drug use, particularly the illicit use of prescription pain medications, by young adults 1–4 years beyond high school, including those in college (Johnston et al., 2010; SAMHSA, 2010d). Whereas men were more likely than women to be hospitalized for alcohol overdoses, women were more likely than men to be treated for overdoses on other drugs. Similar findings have been reported in the literature with regard to the adult population as a whole, not just those ages 18–24. For instance, Coben et al. (2010), using data from the NIS, reported that women are more likely than men to be hospitalized for drug poisonings. Further, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health suggest that young adult women ages 18–25 are less likely than men to use psychotherapeutic drugs (including benzodiazepines and opioid pain medications) recreationally but more likely to use them heavily (Cotto et al., 2010), thereby putting them at greater risk for acute overdose.

Alcohol overdoses were present in one of five drug overdoses, indicating that excessive consumption of alcohol plays a prominent role in many cases of drug overdoses requiring hospitalization. Indeed, the largest increase in rates of overdoses from 1999 to 2008 was not for alcohol alone (25%) or for other drugs alone (55%) but for the combination of alcohol and other drugs (76%). Importantly, the percentage of drug overdose cases in which an alcohol overdose co-occurred increased slightly but significantly from 1999 to 2008. As such, the steep rise in combined alcohol and drug overdoses is partially because of an increase in the likelihood that any given drug overdose case will also include an alcohol overdose. These findings highlight the significant risk, and growing threat to public health, of combining alcohol with other substances. As was the case with alcohol overdose alone, men were more likely than women to be hospitalized for a combined alcohol and drug overdose. Higher rates of combined alcohol and drug overdoses in men could stem from the heavier drinking levels in young men than young women, leading them to be more likely to require hospitalization for alcohol overdoses with or without the presence of other drugs.

Data from the current project and previous studies indicate that overdoses involving prescription opioid pain medications and related narcotic analgesics are on the rise. In the present study, we observed an increase of 122% in the rate of poisonings stemming from prescription opioid pain medications and related narcotics in 18- to 24-year-olds from 1999 to 2008. The CDC reported that more than half of the 27,658 documented drug-poisoning deaths in the United States in 2007 were caused by overdoses on opioid pain medications (CDC, 2010a). The number of deaths caused by opioid pain medications was 1.9 times higher than the number of overdose deaths caused by cocaine and 5.4 times higher than the number of deaths caused by heroin (CDC, 2010a). Data from DAWN revealed 397,160 emergency department visits because of adverse effects of opioids and other prescription narcotic pain medications in 2009, a 154% increase from 2004 (SAMHSA, 2010b). Findings from the present study are in line with data demonstrating a national trend toward increasing rates of misuse of prescription opioid analgesics among young people and highlight the dangers of such misuse (SAMHSA, 2010d).

As with drug overdoses in general, alcohol overdoses were involved in approximately one of five cases of overdoses on opioids and related narcotic analgesics. The level of alcohol involvement in these overdoses did not change over the years. The combination of alcohol with opioids and related narcotics is particularly dangerous because they both suppress activity in brain stem nuclei, including the dorsal and ventral respiratory groups, which regulate breathing. Suppression of these nuclei leads to hypoxia and then death (Miller and Gold, 1991; White and Irvine, 1999). Indeed, a warning about combining alcohol with prescription opioid pain medications is included in the prescribing information provided by drug manufacturers. For instance, the prescribing information for the opioid analgesic Percocet warns, "Oxycodone may be expected to have additive effects when used in conjunction with alcohol, other opioids, or illicit drugs that cause central nervous system depression" (Endo Pharmaceuticals, 2006).

Increases in rates of medication-related overdose deaths contributed to a recent initiative, called the Safe Use Initiative, by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2009). The aim of the initiative is to reduce medication-related adverse events, including unintentional and intentional overdoses. Findings from the current study underscore the fact that alcohol often is present in overdoses involving other drugs, including prescription opioid pain medications. Given the risk of deleterious interactions between alcohol and a wide range of prescription medications, it is imperative that doctors and patients are educated about the risks of consuming alcohol or illicit drugs when taking prescription medications (Paulozzi et al., 2011). Many professional organizations, including the American Medical Association (2010) and the NIAAA (2007) recommend that clinicians ask patients routinely about alcohol use and intervene when such use is unhealthy. D'Amico and colleagues (2005) reported that approximately 29% of all patients, and 36% of patients ages 18–29, who visited their general practitioner in the previous year were asked about their alcohol use. An increase in screening for alcohol misuse would help clinicians identify patients at particularly high risk for excessive drinking and for alcohol and medication interactions. Further, given evidence that early use of alcohol and other drugs is predictive of substance use disorders later in life (Grant and Dawson, 1998; Hingson et al., 2006), clinicians should consider the use of brief intervention techniques to help young adults evaluate their relationship with alcohol and other drugs and make wise choices regarding future use (Bernstein et al., 2010; Monti et al., 2007).

This study focused on alcohol and drug overdoses in young adults ages 18–24. It is beyond the scope of this article to explore overdoses in other age groups in great detail. However, given the sharp increase in overdoses among patients 18–24, analyses were performed to assess how these rates compared with rates of overdoses among patients 25 and older. The outcomes suggest that rates of overdoses increased among all adults in the sample, not just those 18–24. Young adults 18–24 were at greater risk of drug overdoses than adults 25 and older, which is in line with research indicating that drug use peaks during the young adult years (SAMHSA, 2010d). However, alcohol overdoses were less common in those 18–24 than in adults ages 25 and older, as were combined alcohol and drug overdoses. These findings are surprising given that those ages 18–24 are more likely to drink heavily than older adults, to reach criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence than those in other age groups (SAMHSA, 2010d), and to use alcohol and other drugs concomitantly than older subjects (McCabe et al., 2006). Additional research is needed to examine the pattern of alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their combination in finer age ranges among patients 25 and older (25–34, 35–44, etc.) and to explore the factors driving overdoses in patients during various stages of life.

In summary, rates of inpatient hospitalizations for alcohol overdoses, drug overdoses, and their combination increased among 18- to 24-year-olds from 1999 to 2008. Hospitalizations for alcohol overdoses with no other drugs involved increased 25%. Hospitalizations for drug overdoses with no alcohol involved increased 56%. Hospitalizations for combined alcohol and drug overdoses increased the most at 76%. Approximately one in five drug overdose cases involved a concomitant alcohol overdose, indicating that excessive consumption of alcohol plays a prominent role in many cases of drug overdose. The cost of hospital stays stemming from alcohol and drug overdoses exceeded $1.2 billion in 2008. Stronger efforts to educate medical practitioners and the public about the risks of combining alcohol and other drugs could help reduce the number of such hospitalizations.

References

- American Medical Association (AMA) AMA policies on alcohol. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/public-health/promoting-healthy-lifestyles/alcohol-other-drug-abuse/ama-policies-on-alcohol.page.

- Bernstein J, Heeren T, Edward E, Dorfman D, Bliss C, Winter M, Bernstein E. A brief motivational interview in a pediatric emergency department, plus 10-day telephone follow-up, increases attempts to quit drinking among youth and young adults who screen positive for problematic drinking. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17:890–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Unintentional drug poisoning in the United States. 2010a. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/pdf/poison-issue-brief.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: Binge drinking among high school students and adults—United States, 2009. MMWR. 2010b;59(39):1274–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y. Alcohol and injury in the United States general population: A risk function analysis from the 2005 National Alcohol Survey. American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:29–35. doi: 10.1080/10550490802544045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coben JH, Davis SM, Furbee PM, Sikora RD, Tillotson RD, Bossarte RM. Hospitalizations for poisoning by prescription opioids, sedatives, and tranquilizers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:517–524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotto JH, Davis E, Dowling GJ, Elcano JC, Staton AB, Weiss SRB. Gender effects on drug use, abuse, and dependence: A special analysis of results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Gender Medicine. 2010;7:402–413. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S, Johnson CH, Meikle S, Jamieson DJ, Posner SF. Trends in rates of hospitalization with a diagnosis of substance abuse among reproductive-age women, 1998 to 2003. Women's Health Issues. 2007;17:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Paddock SM, Burnam A, Kung F-Y. Identification of and guidance for problem drinking by general medical providers: Results from a national survey. Medical Care. 2005;43:229–236. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and all-cause mortality. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:72–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan J, Bernard A, Olliac B, Mailhes A-S, Kermarrec S. Adolescent brain development, risk-taking and vulnerability to addiction. Journal of Physiology–Paris. 2010;104:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Pharmaceuticals. Percocet. 2006. Retrieved from http://www.endo.com/pdf/products/Percocet_pack_insert_2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gillum BS, Graves EJ, Kozak LJ. Vital and Health Statistics. 124. Vol. 13. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1996. Trends in hospital utilization: United States 1988–92 (DHHS Publication No. PHS 96–1785) pp. 1–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1998;10:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Cost-to-Charge Ratio Files. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age of alcohol-dependence onset: associations with severity of dependence and seeking treatment. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e755–e763. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18– 24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2009: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–50 (NIH Publication No. 10–7585) Retrieved from http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html. [Google Scholar]

- Jones AW, Kugelberg FC, Holmgren A, Ahlner J. Drug poisoning deaths in Sweden show a predominance of ethanol in mono-intoxications, adverse drug-alcohol interactions and poly-drug use. Forensic Science International. 2011;206:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Healthy People Statistical Notes, no. 20. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski A, Ojanperä I, Vuori E. Interaction of alcohol and drugs in fatal poisonings. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2003;22:281–287. doi: 10.1191/0960327103ht324oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski A, Vuori E, Ojanperä I. Relation of postmortem blood alcohol and drug concentrations in fatal poisonings involving amitripty-line, propoxyphene and promazine. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2005;24:389–396. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht542oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DK, Marchell TC. Safety first: A medical amnesty approach to alcohol poisoning at a U.S. university. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:329–338. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ. The relationship between past-year drinking behaviors and nonmedical use of prescription drugs: Prevalence of co-occurrence in a national sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NS, Gold MS. Alcohol. New York, NY: Plenum; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Woolard R. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Nelson DE, Brewer RD. The intensity of binge alcohol consumption among U.S. adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2008.With Chartbook. Hyattsville, MD: 2009. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcohol Alert, 27. Bethesda, MD: Author; 1995. Alcohol-medication interactions. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician s guide, 2005 edition, NIHPublication No. 07-3769. Bethesda, MD: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Parents—Spring break is another important time to discuss college drinking, NIH Publication No. 05-5642. Bethesda, MD: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oster-Aaland L, Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Vangsness J, Larimer ME. Alcohol poisoning among college students turning 21: Do they recognize the symptoms and how do they help? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:122–130. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ, Weisler RH, Patkar AA. A national epidemic of unintentional prescription opioid overdose deaths: How physicians can help control it. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72:589–592. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10com06560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF. Vital and Health Statistics, 10(245). DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 2010–1573. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. Health behaviors of adults: United States, 2005–2007. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_245.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) The DAWN Report: Emergency Department Visits Involving Underage Alcohol Use: 2008. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010a. Retrieved from http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k10/DAWN005/UnderageDrinking.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2009 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2010b. Retrieved from http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k10/DAWN034/ED-Highlights.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2007: National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010c. Retrieved from https://dawninfo.samhsa.gov/files/ED2007/DAWN2k7ED.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010d. (NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586 Findings) Retrieved from http://oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k9nsduh/2k9resultsp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka E. Toxicological interactions between alcohol and benzodi-azepines. Clinical Toxicology. 2002;40:69–75. doi: 10.1081/clt-120002887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Resident Population Estimates of the United States by Age and Sex: April 1, 1990 to July 1, 1999, with Short-Term Projection to November 1, 2000. Release Date: January 2, 2001. 2001. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1990s/nat-agesex.txt.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex and Selected Age Groups for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009. 2010. Table 2. (NC-EST2009–02) Release Date: June 2010. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/NC-EST2009-sa.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA's safe use initiative: Collaborating to reduce preventable harm from medications. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM1 88961.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Kraus CL, Swartzwelder HS. Many college freshmen drink at levels far beyond the binge threshold. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1006–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Irvine RJ. Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose. Addiction. 1999;94:961–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y-H, Stinson FS, Yi H-Y, Dufour MC. Accidental alcohol poisoning mortality in the United States, 1996–1998. Alcohol Research & Health. 2003;27:110–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagrosek A, Messroghli D, Schulz O, Dietz R, Schulz-Menger J. Effect of binge drinking on the heart as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:1328–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]