Abstract

BACKGROUND

Which serologic and clinical findings predict adverse pregnancy outcome (APO) in patients with antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) is controversial.

METHODS

PROMISSE is a multicenter, prospective observational study of risk factors for APO in patients with aPL (lupus anticoagulant [LAC], anticardiolipin antibody [aCL] and/or antibody to β2 glycoprotein I [anti-β2-GP-I]). We tested the hypothesis that a pattern of clinical and serological variables can identify women at highest risk for APO.

RESULTS

Between 2003 and 2011 we enrolled 144 pregnant patients, of whom 28 had APO. Thirty-nine percent of patients with LAC had APO, compared to 3% who did not have LAC (p < 0.0001). Only 8% of women with IgG aCL ≥40 u/mL but not LAC suffered APO, compared to 43% of those with LAC (p = 0.002). IgM aCL or IgG or IgM anti-β2-GP-I did not predict APO. In bivariate analysis, APO occurred in 52% of patients with and 13% of patients without prior thrombosis (p = 0.00005), and in 23% with SLE compared to 17% without SLE (not significant); SLE was a predictor in multivariate analysis. Prior pregnancy loss did not predict APO, nor did maternal race. Simultaneous aCL, anti-β2-GP-I, and LAC did not predict APO better than did LAC alone.

CONCLUSIONS

LAC is the primary predictor of APO after 12 weeks gestation in aPL-associated pregnancies. ACL and anti-β2-GP-I, if LAC is not also present, do not predict APO.

Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL, which include lupus anticoagulant [LAC], IgG and IgM antibodies to cardiolipin [aCL] and IgG and IgM antibodies to β2 glycoprotein I [anti-β2-GP-I]),1 are closely associated with pregnancy complications, but many women with aPL have normal pregnancies. Whether specific serological or clinical findings, such as associated SLE, can predict those patients with aPL who are most likely to suffer adverse pregnancy outcome (APO) is controversial. Retrospective studies have suggested that simultaneous presence of LAC, aCL, and anti-β2-GP-I, of anti-β2-GP-I alone, and of other antibody combinations, identify at risk patients; other studies suggest that clinical characteristics such as SLE or prior pregnancy losses are predictive, and no consensus exists.2–14 Many physicians test all pregnant patients for aPL and treat those who test positive regardless how positivity is defined. Identification of specific predictors of high risk for APO would allow targeting of therapy to those most likely to benefit.

METHODS

Definitions, patient selection and monitoring

The PROMISSE Study (Predictors of pRegnancy Outcome: bioMarkers In antiphospholipid antibody Syndrome and Systemic lupus Erythematosus) is an ongoing multicenter, National Institutes of Health-funded prospective observational study of pregnancies of women with aPL, SLE, or both, as well as healthy pregnant controls. Patients were followed monthly through their pregnancies and data and samples collected. This paper concerns the subset of participants who have aPL of any titer who delivered between September, 2003 and March, 2011.

Seven study sites recruited consecutive pregnant women referred because of a suspected diagnosis of aPL, SLE or both, as well as healthy controls. Gestations of eligible patients had to be 12 weeks or earlier (SLE and normal) or 18 weeks or earlier (aPL patients; 41 of 144 were enrolled between 12 and 18 weeks). Healthy pregnant controls, selected among women with no known illness, no prior fetal loss, no more than one embryonic loss, and at least one successful pregnancy, were tested parallel to the patient groups. One hundred and sixteen women declined to participate.

The choice to exclude patients whose pregnancies ended before 12 weeks was based on the difficulty of identifying and qualifying patients so shortly after diagnosis of pregnancy and the high frequency of early miscarriage due to chromosome errors or unidentifiable causes among normal women, which would markedly increase the resources needed to screen such candidates.8, 11 The choice to include aPL patients up to 18 weeks was made at the request of the NIH-appointed Observational Study Monitoring Board after the first interim analysis noted slow recruitment due in part to exclusion of pregnancies after 12 weeks and because very few APOs occurred in this interval.

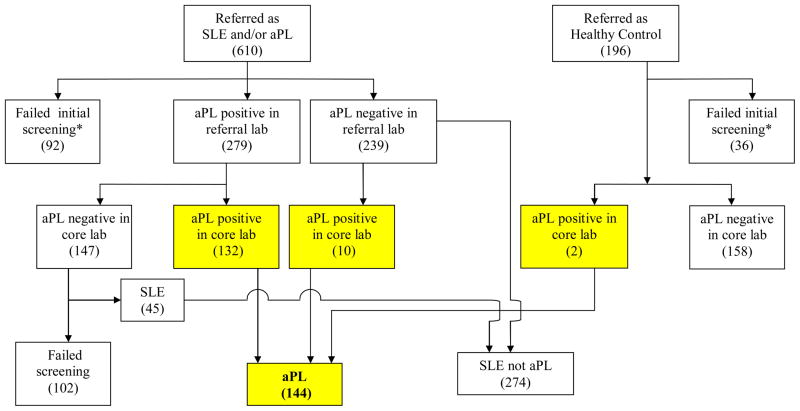

SLE was diagnosed if patients fulfilled four or more of the American College of Rheumatology criteria for classification of SLE.15 Figure 1 indicates derivation of the study groups.

Figure 1.

Selection of patients for this study. Numbers indicate patients in each box.

*Reasons for failed screening: blighted ovum, pregnancy not confirmed, pregnancy loss before 12 weeks, multiple gestations, declined consent, did not meet 4 ACR criteria for SLE, enrollment exclusion (prednisone >20 mg/day, blood pressure >140/90, protein/creatinine ratio >1000 mg protein/gram creatinine on 24 hour urine or spot urine, serum creatinine >1.2, screened too late in pregnancy, history of fetal death [healthy controls]).

Inclusion criteria were: confirmed positive aPL at two or more separate time points and at least one positive result in the core laboratories (see below) during pregnancy, live intrauterine pregnancy, confirmed by ultrasound, age 18–45 years, ability to give informed consent, and hematocrit >26%. Exclusion criteria, chosen so that other non-aPL causes of APO would not confound the findings were: treatment with prednisone >20 mg/day, urine protein ≥1000 mg in 24 hours or protein/creatinine ratio ≥1000 mg protein/gram creatinine on spot urine sample; erythrocyte casts in urinalysis; serum creatinine >1.2 mg/dL; type I or II diabetes mellitus antedating pregnancy, blood pressure ≥140/90 mm mercury at the screening visit, and multi-fetal pregnancy. Patients were evaluated monthly by an obstetrician and each trimester by a rheumatologist through three months postpartum with physician examination, questionnaires, obstetric ultrasounds and laboratory testing.

At the time this study was initiated the 1999 (Sapporo) Criteria16 for the classification of APS required positive tests to be replicable at intervals no less than 6 weeks and aCL and anti-β2-GP-I to be moderate to high titer (≥40 units). Because the study was ongoing, we retained the 1999 definitions. A 2006 revised consensus conference report changed the interval to 12 weeks and suggested that anti-β2-GP-I be reported as percentiles.1

The Institutional Review Board at each of the PROMISSE Study sites approved participation of patients. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

APO was defined as an otherwise unexplained fetal demise after 12 weeks, neonatal death prior to discharge, associated with complications of prematurity, preterm delivery prior to 34 weeks because of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia or placental insufficiency, and small for gestational age (birth weight <5th percentile using the Alexander, et al., table for Smoothed Percentiles of Birth Weight by Gestational Age).17–19 Obstetrical members of the PROMISSE team adjudicated causes of fetal demise in equivocal cases.

Antiphospholipid antibody tests

In this paper we report only core laboratory data obtained at screening visit; analyses for other time points did not change the conclusions.

Blood samples were immediately processed and shipped on dry ice and maintained frozen at −80° C until tested.

Lupus anticoagulant

The LAC core lab is directed by CAL in Toronto.21 LAC was detected using a panel of three tests including the dilute Russell’s viper venom time (dRVVT), a lupus anticoagulant-sensitive partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and the dilute prothrombin time (dPT), using previously published methods that fulfill criteria proposed by The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.22 Based on mixing studies and phospholipid dependence, LAC is determined to be present or absent.

LAC values measured throughout pregnancy and postpartum at the core lab did not change after initiation of either low molecular weight or unfractionated heparin therapy; addition of heparinase to plasma from patients on heparin confirmed lack of effect by heparin on LAC. Plasmas spiked with appropriate amounts of heparin indicated that heparin treatment did not cause false positive LAC tests. No patients developed LAC upon introduction of either low molecular weight or unfractionated heparin. The reagents used to screen and confirm LAC contain polybrene, which inactivates heparin at 1–2 U/ml, higher than the typical therapeutic range of 0.3–0.7 U/ml. No patient was taking warfarin when tested.

Anticardiolipin antibody was tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for cardiolipin in the laboratory of JES in New York, as published23 and validated in international standardization workshops.24 Normal levels for the individual tests are based on 3 standard deviations of a panel of normal controls and are: IgG aCL 0–20 u/mL, IgM aCL 0–10 u/mL.

Anti-β2-GP-I was tested in the laboratory of JM at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. A Nunc maxisorb microtitre plate is coated with beta 2 glycoprotein 1 antigen diluted in BBS(Borate buffered saline) pH 9.6, and incubated at 4oC overnight. A six-point standard curve is prepared using an in-house calibrator initially diluted 1:100 in BBT (0.5% BSA, BBS, 1.2% Tween80). The plate is then washed two times with BBS. Test samples at 1:100, quality control samples (known positives and negatives) are added at 1:100 and standard curve serial dilution sera samples are added (final volume for each sample, 200 μl/well). All samples are tested in duplicate. The plate is incubated 2 hours at room temperature. At end of incubation the plate is washed a further three times, after which, 100 μl of working strength detection antibody (goat anti-Human IgG or M alkaline phosphatase conjugate, Sigma) is added to each well, and incubated for a further one and half hours at room temperature. Three more washes are performed and the reaction is visualized by the addition of 75 μl/well of diethanolamine substrate buffer containing p-NPP (p-nitrophenylphosphate, Sigma). Absorbance is read at 405 nm on a BIO-TEK ELx808 automated microplate reader.25 Normal was two standard deviations from the mean of 60 normal controls. Normal levels for IgG anti-β2-GP-I are 0–25 u/mL and IgM anti-β2-GP-I 0–25 u/mL. Concordance between core laboratory determination of anti-β2-GP-I and simultaneously performed assays at the Hospital for Special Surgery and commercially performed assays by Quest Diagnostics was >80%.

In accordance with international criteria for both IgG or IgM aCL and anti-β2-GP-I aPL, ≥40 u/mL are considered high titer positive tests and <40 u/ml low titer.1

Treatment

The patients’ physicians made all treatment decisions without knowledge of core laboratory results. Fifty-six of the 75 patients using heparin at first study visit received low molecular weight heparin and 19 unfractionated heparin; 36 received therapeutic doses and 39 prophylactic doses. All but one of 97 patients who took aspirin took 81 mg per day; the other took 325 mg per day (Table 1).

Table 1.

Adverse pregnancy outcome in patients with aPL, displayed as a function of clinical, serological, and treatment characteristics at first study visit. LAC and prior thrombosis are strongly associated with higher incidence of APO. LMWH, low molecular weight. UFH, unfractionated heparin.

| CHARACTERISTIC | TOTAL n | APO n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| ALL | 144 | 28 (19) | ||

| Demographic | Race | |||

| White | 117 | 26 (22) | ||

| Non-white | 27 | 2(7) | 0.11 | |

| Age | ||||

| < 30 years | 48 | 14 (29) | ||

| ≥ 30 years | 96 | 14 (15) | 0.05 | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical | SLE | |||

| Absent | 87 | 15 (17) | ||

| Present | 57 | 13 (23) | 0.52 | |

| Prior thrombosis | ||||

| No | 119 | 15 (13) | ||

| Yes | 25 | 13 (52) | 0.00005 | |

| Prior pregnancies | ||||

| 0 | 31 | 7 (23) | ||

| 1 | 34 | 6 (18) | ||

| 2 | 37 | 8 (22) | ||

| 3+ | 42 | 7 (17) | 0.90 | |

| Prior pregnancy losses | ||||

| 0 | 56 | 10 (18) | ||

| 1 | 41 | 8 (20) | ||

| 2+ | 47 | 10 (21) | 0.96 | |

| Serology | LAC | |||

| Negative | 76 | 2 (3) | ||

| Positive | 64 | 25 (39) | <0.0001 | |

| aCL IgG | ||||

| <40 u/mL | 77 | 9 (12) | ||

| With LAC | 26 | 9 (35) | ||

| Without LAC | 50 | 0 (0) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥40 u/mL | 66 | 19 (29) | 0.01 | |

| With LAC | 37 | 16 (43) | ||

| Without LAC | 26 | 2 (8) | 0.002 | |

| aCL IgM | ||||

| <40 u/mL | 120 | 24 (20) | ||

| With LAC | 51 | 21 (41) | ||

| Without LAC | 66 | 2 (3) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥40 u/mL | 23 | 4 (17) | 1.00 | |

| With LAC | 12 | 4 (33) | ||

| Without LAC | 10 | 0 (0) | 0.10 | |

| aβ2-GP-1 IgG | ||||

| <40 u/mL | 106 | 16 (15) | ||

| With LAC | 36 | 13 (36) | ||

| Without LAC | 66 | 2 (3) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥40 u/mL | 37 | 11 (30) | 0.09 | |

| With LAC | 27 | 11 (41) | ||

| Without LAC | 10 | 0 (0) | 0.02 | |

| aβ2-GP-1 IgM | ||||

| <40 u/mL | 121 | 21 (17) | ||

| With LAC | 49 | 19 (39) | ||

| Without LAC | 68 | 1 (2) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥40 u/mL | 22 | 6 (27) | 0.37 | |

| With LAC | 14 | 5 (36) | ||

| Without LAC | 8 | 1 (13) | 0.35 | |

| Treatment | Heparin | |||

| No | 69 | 8 (12) | ||

| Yes | 75 | 20 (27) | 0.03 | |

| Aspirin | ||||

| No | 47 | 14 (30) | ||

| Yes | 97 | 14 (14) | 0.04 | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | ||||

| No | 110 | 23 (21) | ||

| Yes | 34 | 5 (15) | 0.62 | |

| Corticosteroid | ||||

| No | 121 | 26 (21) | ||

| Yes | 23 | 2 (9) | 0.25 | |

Statistical analyses

The Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate bivariate associations between categorical variables. Multivariable analyses were performed by fitting a Poisson regression model with a robust error variance to estimate the relative risk for an exposure variable adjusted for the effects of other covariates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.26 Variables which were predictive of APO in bivariate analyses (p < 0.20) as well those deemed to be associated with APO a priori based on clinical factors, were considered for inclusion in the model. The final model was determined using a backward selection approach and included only those covariates which remained significant at the p< 0.05 level. An internal validation of the predictive model was also performed using a 5-fold cross-validation procedure. The model was re-fit at each step of the validation using the training data, and evaluated on the corresponding test set. Results of the validation procedure are reported as the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the model averaged over all test sets.

RESULTS

Study population

PROMISSE recruited 806 consecutive women referred for pregnancies associated with aPL, SLE or both, or who were normal controls (Figure 1). APL was confirmed in the core laboratories in 144 patients, of whom 87 had aPL only and 57 had aPL and SLE (Figure 1 and Table 1). Six screened patients confirmed to have aPL and 3 suspected to have aPL but not confirmed in core laboratories lost their pregnancies before 12 weeks and were excluded from analysis. Two of the normal controls repeatedly had positive aCL tests and were added to the aPL group.

aPL tests

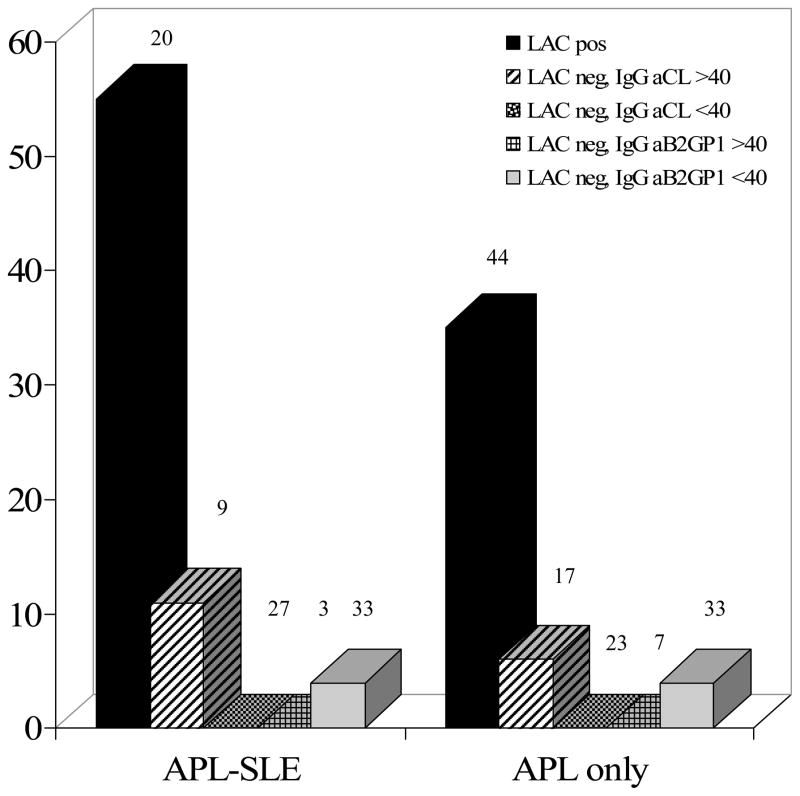

Twenty-eight (19%) of 144 patients with aPL at screening had APO, compared to 3 of 159 (2%) normal controls (p <0.0001). Sixty-four aPL patients had LAC, (Table 1), of whom 25 (39%) had APO, compared with 2 of 76 (3%) LAC-negative women (p < 0.0001, 1 patient with missing LAC data at screening). Of 66 women with IgG aCL antibody ≥40 u/mL 19 (29%) had APO, whereas only 9 of 77 (12%) with aCL <40 u/mL had APO (p=0.01, Table 1). All 9 APO cases with IgG aCL <40 u/mL were LAC positive; among those with IgG aCL ≥40 u/mL, the APO rate was 8% in the LAC negative group compared to 43% in the LAC positive group (p = 0.002). IgM aCL ≥40 u/ML and IgG or IgM anti-β2-GP-I did not predict APO, nor did a combination of tests have better predictive power than did LAC alone (data not shown). DPT, APTT, and dRVVT were similar in their abilities to predict APO (Table 2). DPT was the only test positive in 23 patients, of whom 6 had APO.

Table 2.

Association with APO of different screening tests for LAC. No single test identified all patients with APO.

| Assay | No. Positive | No. APO (%) | No. Negative | No. APO (%) | P | % of all APO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dPT | 54 | 21 (39) | 84 | 5 (6) | <0.0001 | 78% |

| dRVVT | 24 | 14 (58) | 112 | 11 (10) | <0.0001 | 52% |

| aPTT (sensitive) | 36 | 17 (47) | 102 | 10 (10) | <0.0001 | 63% |

Analysis for aPL tests at other times in the pregnancy, or for consistently versus transiently positive, did not alter the results. IgM aCL, IgG and IgM aβ2GP-1 each failed to identify patients at risk (Table 1). All other normal and SLE patients had negative tests for aPL.

Clinical and demographic variables

Twenty-five aPL patients had prior thromboses (4 arterial only, 14 venous only, 5 arterial and venous and 2 unknown). Thirteen of 25 (52%) patients with prior thrombosis had APO, compared to 15 of 119 (13%) without (p = 0.00005). In bivariate analyses prior fetal loss and non-white race did not distinguish among patients with or without APO (Table 1). All 5 patients who had LAC, SLE, and prior thrombosis had APO compared to 1 of 38 patients who lacked all three of these characteristics. SLE did not affect APO rate in bivariate analyses, nor did treatment with corticosteroid or hydroxychloroquine; patients receiving (at first study visit) aspirin had a lower and those receiving heparin a higher rate of APO (Table 1).

Of the 28 patients with APO, 14 had fetal death, 1 neonatal death, 16 delivery before 34 weeks, 12 preeclampsia or gestational hypertension leading to delivery before 34 weeks, 5 placental insufficiency, and 4 fetal growth restriction <5th percentile (events are double-counted), with no pattern evident between type of APO event and serology, but the numbers are small.

Multivariable analyses

Multivariable analyses were performed by fitting Poisson regression models. The final model included screening LAC status (RR = 12.15; 95% CI: 2.92–50.54; p = 0.0006), history of thrombosis (RR = 1.90; 95% CI: 1.14–3.17; p = 0.01), SLE (RR = 2.16; 95% CI: 1.27–3.68; p = 0.005), age (RR = 1.56 for every 5 years decrease in age; 95% CI: 1.18–2.08; p = 0.002), and race (RR=3.24 for white vs. non-white; 95% CI: 1.16–9.07;p=0.03). The area under the ROC curve for this model was 0.90, indicating a high ability to discriminate between patients with and without APO (Figure 2). The accuracy of the model averaged across the test sets in the 5-fold cross-validation procedure was 78% (sensitivity: 71%; specificity: 80%) using the cutpoint on the ROC curve closest to (0,1); i.e., perfect sensitivity and specificity, as the threshold for classification. Heparin (RR = 0.94; 95% CI: 0.42–2.13; p = 0.88) was not associated with risk of APO after adjusting for the same variables nor were IgG or IgM levels of aCL and anti-β2-GP-I. The protective effect of aspirin was also no longer significant after adjusting for the predictors in the final model (RR=0.64; 95% CI: 0.36–1.12; p=0.12).

Figure 2.

Percent adverse pregnancy outcome in SLE-APL and APL-only patients as a function of serologic status at screening. Numbers represent the number of patients fulfilling the serologic criterion for each bar. LAC was the strongest predictor of APO.

Similar multivariate results were obtained when APO included mild (delivery after 34 weeks because of preeclampsia and growth restriction) and severe (fetal or neonatal death or delivery before 34 weeks) events with RR for screening LAC = 2.76; 95% CI: 1.55–4.91; p = 0.0006.

DISCUSSION

In 1980 Soulier and Boffa described an association between LAC and recurrent pregnancy loss,27 confirmed initially by case reports and later by clinical series associating aPL with (generally second trimester) pregnancy loss, fetal growth restriction, and severe preeclampsia.28 No consensus exists concerning which if any autoantibody profiles predict outcome of aPL-associated pregnancies;4–14 a recent retrospective analysis of 38 patients tested for LAC, aCL and anti-β2GP-I argued that triple positivity is the best predictor,4,5 and a study from Saudi Arabia argued for broadly-defined LAC.14

Our prospective, rigorously defined study, with all laboratory studies performed in central core laboratories, finds that women who have LAC at screening are at highest risk for APO, that LAC-negative women, regardless of IgG or IgM aCL or anti-β2GP-I are not at high risk, and that LAC is the only component of triple positivity that has predictive power. Although some have suggested that anti-β2GP-I should be the most predictive antibody, 29, 30 our findings do not confirm this hypothesis.

Strengths of this study its prospective design, its size, its rigorous clinical definitions, its consideration of multiple clinical variables, and its use of core laboratories. A weakness is that our study is referral center-based and treatment was directed by the patients’ physicians. In these respects, however, our study does not differ from prior publications on this topic. Our use of multivariate analysis allowed us to stratify patients by serological and clinical features and by treatment, and our conclusions regarding LAC still hold. In order not to confound aPL-associated causes of APO with other causes, such as pre-existing hypertension, diabetes, renal failure or multigestational pregnancies, we excluded patients with such conditions, and we were unable to study patients with early pregnancy losses. Our conclusions therefore apply to relatively well women with aPL after the 12th week of pregnancy.

Unexpectedly, we did not see a beneficial effect of heparin treatment on APO. Our study was not designed nor powered as a treatment trial, patients were not randomly allocated to treatment arms, and numbers are small, so our findings with regard to heparin are at best hypothesis-generating. Possibly these results reflect physician choice to use heparin selectively in patients at higher risk for reasons not identified by our criteria, or that heparin is less effective than is currently assumed.

Our definition of LAC required positivity in one of three assays. Consensus recommendations regarding diagnosis of LAC are not widely used by commercial or by our university hospital laboratories31, 32 nor do they account well for reagent variation or for quantitative and qualitative differences among LACs diagnosed by different assays.33, 34 Collectively, our three screening tests identified 93% of patients who suffered APO. Individually, dRVVT identified 52%, aPTT 63%, and dPT 78%. Thus, in clinical use, a negative test performed by only one method is not fully reassuring. Since insurers often will not pay for more than a single test, and laboratories rarely offer an option to perform multiple tests, clinicians must retain a high level of concern; on the other hand, any positive test for lupus anticoagulant is clear evidence for pregnancy risk.

Measurement of aCL and aβ2 GP-I by commercial laboratories is also problematic, as shown by our finding that 40% of referred patients with other laboratory-identified aPL had negative tests in our core laboratory. We and others have previously commented on the inconsistencies of laboratories in measuring aPL.35, 36 Because we report our aPL only as confirmed in our core laboratories, and because we cross-checked core laboratory results with known reliable other laboratories, we believe the results we reported are as close to true determinations of aPL as possible.

Among aPL-bearing patients, with or without SLE, LAC, with or without other aPL antibodies, is the primary predictor of APO. Prior thrombosis, SLE, age and race are lesser contributors to risk. Future treatment trials should consider these risk factors, and clinicians should treat only those patients truly at high risk.37

Acknowledgments

Supported by: NIH/NIAMS RO1 AR49772 (PROMISSE Study, MDL, MK, DWB, JB, MG, CL, JM, MP, FP, LS, MDS, JES), Mary Kirkland Center for Lupus Research (JES, MDL), Rheuminations, Inc. (JES), Barbara Volcker Center for Women and Rheumatic Disease (MDL)

The authors wish to thank Christine Clark for performing and interpreting LAC assays, and Emily Reeves, Vamsy Bobba, Karen Spitzer for assistance in recruiting patients

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00198068

Contributor Information

Michael D. Lockshin, Hospital for Special Surgery and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

Mimi Kim, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

Carl A. Laskin, University of Toronto, Toronto

Marta Guerra, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York.

D. Ware Branch, University of Utah Health Sciences Center and Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City.

Joan Merrill, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation and the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City.

Michelle Petri, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Flint Porter, University of Utah Health Sciences Center and Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City.

Lisa Sammaritano, Hospital for Special Surgery and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

Mary D. Stephenson, University of Chicago, Chicago

Jill Buyon, New York University School of Medicine, New York.

Jane E. Salmon, Hospital for Special Surgery and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

References

- 1.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derksen RH, de Groot PG. The obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;77:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tincani A, Bazzani C, Zingarelli S, Lojacono A. Lupus and the antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy and obstetrics: clinical characteristics, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008;34:267–73. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1082270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruffatti A, Calligaro A, Hoxha A, Trevisanuto D, Ruffatti AT, Gervasi MT, et al. Laboratory and clinical features of pregnant women with antiphospholipid syndrome and neonatal outcome. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:302–307. doi: 10.1002/acr.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruffatti A, Tonello M, Visentin MS, Bontadi A, Hoxha A, De Carolis S, et al. Risk factors for pregnancy failure in patients with anti-phospholipd syndrome treated with conventional therapies: a multicentre, case-control study. Rheumatology. 2011;50:1684–1689. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branch DW. Antiphospholipid antibodies and fetal compromise. Thromb Res. 2004;114:415–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meroni PL, di Simone N, Testoni C, D’Asta M, Acaia B, Caruso A. Antiphospholipid antibodies as cause of pregnancy loss. Lupus. 2004;13:649–52. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu2001oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephenson MD. Frequency of factors associated with habitual abortion in 197 couples. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:24–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rai R, Cohen H, Dave M, Regan L. Randomised controlled trial of aspirin and aspirin plus heparin in pregnant women with recurrent miscarriage associated with phospholipid antibodies (or antiphospholipid antibodies) BMJ. 1997;314:253–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7076.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kutteh WH. Antiphospholipid antibody-associated recurrent pregnancy loss: treatment with heparin and low-dose aspirin is superior to low-dose aspirin alone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1584–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70610-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oshiro BT, Silver RM, Scott, Yu H, Branch DW. Antiphospholipid antibodies and fetal death. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:489–93. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruffatti A, Tonello M, Del Ross T, et al. Antibody profile and clinical course in primary antiphospholipid syndrome with pregnancy morbidity. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:337–41. doi: 10.1160/TH06-05-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Do Prado AD, Piovesan DM, Staub HL, Horta BL. Association of anticardiolipin antibodies with preeclampsia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1433–43. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fe02ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Mishari AA, Gader AG, Al-Jabbari AW, et al. The prevalence of lupus anticoagulant in normal pregnancy and in women with recurrent fetal loss--recommendations for laboratory testing for lupus anticoagulant. Ann Saudi Med. 2004;24:429–33. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2004.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson WA, Gharavi AE, Koike T, et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1309–11. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1309::AID-ANR1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACOG practice bulletin. Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Number 33, January 2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:163–8. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Intrauterine Growth Restriction. ACOG Practice Bulletin. 2000;12 [Google Scholar]

- 20.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 58. Ultrasonography in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1449–58. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200412000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark-Soloninka C, Spitzer K, Nadler J, Laskin C. Evaluation of screening 590 plasma samples for the lupus anticoagulant using a panel of four tests. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1998;41(Supplement):S168. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pengo V, Tripodi A, Reber G, Rand JH, Ortel TL, Galli M, De Groot PG Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibody of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection. Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/ Antiphospholipid Antibody of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2009 Oct;7(10):1737–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03555.x. Epub 2009 Jul 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qamar T, Levy RA, Sammaritano L, Gharavi AE, Lockshin MD. Characteristics of high-titer IgG antiphospholipid antibody in systemic lupus erythematosus patients with and without fetal death. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:501–4. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris EN. The Second International Anti-Cardiolipin Standardization Workshop/The Kingston Anti-Phospholipid Antibody Study (KAPS) Group. Amer J Clin Pathol. 1990;94:476–484. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/94.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erkan D, Zhang HW, Shriky RC, Merrill JT. Dual antibody reactivity to beta2-glycoprotein I and protein S: increased association with thrombotic events in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2002;11:215–20. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu178oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soulier J, Boffa M. Avortements à repetition, thromboses et anticoagulant circulant antithromboplastine. Nouv Presse Med. 1980;9:859–864. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganzevoort W, Rep A, De Vries JI, Bonsel GJ, Wolf H. Relationship between thrombophilic disorders and type of severe early-onset hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Hypertens. doi: 10.1080/10641950701521601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alijotas-Reig J, Ferrer-Oliveras R, Rodrigo-Anoro MJ, Farran-Codina I, Cabero-Roura L, Vilardell-Tarres M. Anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein-I and anti-phosphatidylserine antibodies in women with spontaneous pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2330–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agostinis C, Biffi S, Garrova C, Durigutto P, Lorenzon A, Bek A, et al. In vivo distribution of (beta)2 glycoprotein I under various pathophysiologic conditions. Blood. 2011;118:4231–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-333617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dembitzer FR, Ledford Kraemer MR, Meijer P, Peeerschke EI. Lupus anticoagulant testing: performance and practices by North American clinical laboratories. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:764–73. doi: 10.1309/AJCP4SPPLG5XVIXF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moffat KA, Ledford-Kraemer MR, Plumhoff EA, McKay H, Nichols WL, Meijer P, Hayward CP. Are laboratories following published recommendations for lupus anticoagulant testing? An international evaluation of practices. Thromb Haemost. 2009 Jan;101(1):178–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Triplett DA. Use of the dilute Russell viper venom time (dRVVT): its importance and pitfalls. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:173–8. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripodi A. Laboratory testing for lupus anticoagulants: a review of issues affecting results. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1629–35. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.089524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erkan D, Derksen WJM, Kaplan V, Sammaritano L, Pierangeli SS, Roubey R, Lockshin MD. Real world experience with antiphospholipid antibody tests: how stable are results over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.031856. e-pub 31856 June 28 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erkan D, Barbhaiya M, George D, Sammaritano L, Lockshin M. Moderate versus high-titer persistently anticardiolipin antibody positive patients: are they clinically different and does high-titer anti-beta 2-glycoprotein-I antibody positivity offer additional predictive information? Lupus. 2010;19:613–9. doi: 10.1177/0961203309355300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lassere M, Empson M. Treatment of antiphospholipid syndrome in pregnancy--a systematic review of randomized therapeutic trials. Thromb Res. 2004;114:419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]