Abstract

Individual variation in sensitivity to acute ethanol (EtOH) challenge is associated with alcohol drinking and is a predictor of alcohol abuse. Previous studies have shown that the C57BL/6J (B6) and 129S1/SvImJ (S1) inbred mouse strains differ in responses on certain measures of acute EtOH intoxication. To gain insight into genetic factors contributing to these differences, we performed quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis of measures of EtOH-induced ataxia (accelerating rotarod), hypothermia, and loss of righting reflex (LORR) duration in a B6 × S1 F2 population. We confirmed that S1 showed greater EtOH-induced hypothermia (specifically at a high dose) and longer LORR compared to B6. QTL analysis revealed several additive and interacting loci for various phenotypes, as well as examples of genotype interactions with sex. QTLs for different EtOH phenotypes were largely non-overlapping, suggesting separable genetic influences on these behaviors. The most compelling main-effect QTLs were for hypothermia on chromosome 16 and for LORR on chromosomes 4 and 6. Several QTLs overlapped with loci repeatedly linked to EtOH drinking in previous mouse studies. The architecture of the traits we examined was complex but clearly amenable to dissection in future studies. Using integrative genomics strategies, plausible functional and positional candidates may be found. Uncovering candidate genes associated with variation in these phenotypes in this population could ultimately shed light on genetic factors underlying sensitivity to EtOH intoxication and risk for alcoholism in humans.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00335-012-9394-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Multiple factors influence the propensity to consume alcohol and the risk for developing an alcohol use disorder. Of these, decreased sensitivity to acute alcohol challenge has been found to be a predictor of risk for alcohol abuse (Newlin and Thomson 1990; Schuckit 1994). Increased sensitivity to the unpleasant subjective effects of intoxication, such as ataxia and sedation, has been posited to serve as a protective influence by discouraging drinking (Krystal et al. 2003). However, the relationship between sensitivity and drinking holds in some, but not all, cases of altered ethanol (EtOH)-related behaviors in various rodent stocks (reviewed in Crabbe et al. 2006). Nonetheless, understanding the neurobiological basis of sensitivity could provide insight into the etiology and pathophysiology of alcohol abuse.

Since the observation that inbred mouse strains exhibit marked differences in voluntary EtOH consumption (e.g., Belknap et al. 1993; McClearn and Rodgers 1959), inbred mice have been utilized as a tool to study the genetics of multiple alcohol-related phenotypes, including sensitivity to intoxication (e.g., Bachmanov et al. 2002; Crabbe 1983; Crabbe et al. 2005; Kakihana et al. 1966; Milner and Buck 2010; Tabakoff et al. 2008). However, the underlying genetics of these traits is still not well understood despite the increasing availability of techniques for studying gene–phenotype relationships.

In this context, we previously reported that two inbred mouse strains, C57BL/6J (hereafter abbreviated B6) and 129S1/SvImJ (hereafter abbreviated S1), differ markedly in sensitivity to acute EtOH intoxication (Chen and Holmes 2009; Palachick et al. 2008). In these studies, this difference in sensitivity was evidenced by increased loss of righting reflex (LORR) responses in S1, relative to B6, in response to a moderate–high dose (3 g/kg) of EtOH. By contrast, B6 and S1 did not vary in hypothermic responses to the same (3 g/kg) dose or in ataxia responses to a 1.75 g/kg dose, consistent with a specific pharmacodynamic, rather than general pharmacokinetic, difference between the two strains. These data are generally consistent with the findings of Crabbe and colleagues obtained from a larger inbred strain comparison in which the authors also observed relatively greater responses in S1 than in B6 on various EtOH behaviors (Crabbe et al. 2003a, b, 2005; Metten et al. 2004; Rustay et al. 2003).

Quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis has been employed as a useful approach to leveraging strain differences to uncover genetic influences underlying variation in alcohol-related phenotypes (Plomin and McClearn 1993). The discovery of QTLs associated with such traits provides a foundation for the identification of specific candidate genes (Shirley et al. 2004). These candidates are likely of relevance to genes underlying variation in alcohol-related behaviors and risk for alcoholism in human populations (Ehlers et al. 2010). Because verification and refinement of such QTLs is facilitated by comparison across different intercrossed populations, the aim of the current study was to employ this approach in order to identify QTLs associated with variation in sensitivity to acute EtOH challenge in a novel F2 population of B6 × S1 mice. We examined the population on multiple phenotypes (ataxia, hypothermia, and LORR) given evidence that different behavioral end-point measures of sensitivity are genetically dissociable (Crabbe et al. 1996, 2005).

Materials and methods

General procedures

A battery of three assays for intoxication was employed: EtOH-induced ataxia, hypothermia, and LORR. All mice were tested on each assay with the assay involving the lowest dose (i.e., ataxia) first, followed by hypothermia and then LORR, with an interval of at least 1 week between tests. Long-term tolerance to EtOH’s effects was not expected to occur with this test and treatment regimen (Crabbe 2007). For all assays, EtOH (200 proof, prepared in 0.9% saline to produce 20% v/v solutions) was administered via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with dose determined by manipulating the volume of injection.

These and all experimental procedures were approved by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Animal Care and Use Committee and strictly followed the NIH guidelines “Using Animals in Intramural Research.”

EtOH-induced ataxia

The accelerating rotarod was used to test for EtOH-induced ataxia, using procedures described previously (Hefner and Holmes 2007). The apparatus used was a Med Associates rotarod typically used for testing rats (model ENV-577, Med Associates, St. Albans, VT), with a 7-cm-diameter dowel covered with 320-grit sandpaper providing a uniform surface that prevented gripping the dowel, as recommended to improve the validity of the assay (Rustay et al. 2003). Mice were placed onto the rotarod dowel which was then accelerated at a constant rate of 8 rpm/min up to 40 rpm. Latency to fall to the floor 10.5 cm below was automatically recorded by photocell beams, with a maximum cutoff latency of 5 min. Mice first received ten consecutive training trials separated by a 30 s intertrial interval. The average latency to fall over the ten training trials was calculated. In addition, the change in latency to fall from the first to the last trial (called the training index) was taken as a measure of motor learning.

Twenty-four hours after training, mice were given an acclimation trial followed by two more pre-EtOH trials that were averaged to establish pre-EtOH performance, and then they were injected with 2.0 g/kg EtOH. Thirty minutes later there was an acclimation trial followed by two test trials that were averaged to get the post-EtOH performance. The dependent measure was the difference between the pre- and post-EtOH performance averages, called the ataxia index.

EtOH-induced hypothermia

EtOH-induced hypothermia was tested as previously described (Boyce-Rustay et al. 2008b) in a room with an ambient temperature of 23°C. Basal core body temperature was taken by inserting a Thermalert TH-5 thermometer (Physitemp, Clifton, NJ) 2 cm into the rectum until a stable reading was obtained. Mice were then injected with 3.5 g/kg EtOH and temperature was measured 30, 60, 90, and 120 min later. The difference (delta temperature) between pre-EtOH temperature and the average temperature over the 4 post-EtOH time points was taken as the dependent measure.

EtOH-induced LORR

EtOH-induced LORR was assessed using methods described previously (Daws et al. 2006). Mice were injected with 3.5 g/kg EtOH and immediately placed into the supine position in a V-shaped chamber. LORR duration was measured as the time from injection to recovery of the righting reflex (i.e., turning onto all four paws twice in 30 s after initial self-righting), with a maximum latency of 180 min before the experiment was terminated.

At LORR recovery mice were killed via cervical dislocation and rapid decapitation. Trunk blood was taken for analysis of blood EtOH concentrations (BECs) using the Analox AM1 Alcohol Analyzer (Analox Instruments USA Inc., Lunenburg, MA).

Parental strain dose-response comparison

As noted in the Introduction, we previously reported that B6 and S1 differ in the LORR response to 3 mg/kg EtOH, but not in either the hypothermia response to 3 mg/kg EtOH or the ataxic response to 1.75 g/kg EtOH (Chen and Holmes 2009; Palachick et al. 2008). To confirm these differences and extend the strain comparison to higher doses, we compared male B6 and S1, obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), for responses in each assay to two different EtOH doses: ataxia (1.75 or 2.0 mg/kg), hypothermia (3.0 or 3.5 mg/kg), and LORR (3.0 or 3.5 mg/kg) (n = 8 per strain, per dose). Other than dose, procedures were as described above.

In addition, to exclude potential EtOH pharmacokinetic differences between S1 and B6, EtOH metabolism was assessed in a separate cohort of EtOH-naïve mice by measuring BECs at various time points following injection with 3.5 g/kg EtOH. Specifically, BECs were measured 5, 30, 60, and 240 min following injection of 3.5 g/kg EtOH, as described previously (Boyce-Rustay and Holmes 2006). To avoid trauma to any single region and conform to local ACUC regulations, blood samples were taken from the submandibular vein at 5 and 30 min, from the tail at 60 min, and from the trunk (after rapid cervical dislocation and rapid decapitation) at 240 min. BECs were measured using the Analox AM1 Alcohol Analyzer.

F2 phenotype

F1 mice were bred in-house from B6 and S1 mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. F2 mice were bred in-house from 16 F1 × F1 breeding pairs. We generated and analyzed 346 F2 mice (183 males, 160 females) derived from 39 separate litters. For comparison with the F2, 11 B6, 8 S1 (obtained from The Jackson Laboratory), and 8 F1 (bred in-house) male mice were tested concomitantly with the F2 mice.

Mice were group-housed by sex and litter in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on 0600 h) with ad libitum access to food and water. Testing began when mice were at least 2 months of age, with a test range of 2–8 months necessitated by the practicalities of testing a large number of mice. Potential age (or litter) effects were not systemically tested for. Note that all F1 and F2 mice had been previously tested (data unpublished) for Pavlovian fear extinction (procedure as in Camp et al. 2009). Our goal was to fully utilize the generation of this large F2 population by examining two phenotypic domains (fear and EtOH sensitivity) in which B6 and S1 differ markedly (Palachick et al. 2008; Whittle et al. 2010).

Statistical analysis of phenotype data

The effect of the training trial on rotarod latency to fall was analyzed using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The effect of strain on EtOH-induced ataxia, hypothermia, LORR, and BECs at recovery was analyzed using ANOVA followed by Fisher’s Least-Significant Difference post-hoc tests. The effect of strain and time-point effects on BECs was analyzed using ANOVA, with repeated measures for time point.

Genotyping analysis

Tail samples were obtained from F2 mice and shipped to the Cancer Animal Models Core Facility at Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta, GA) for processing and analysis. Tail samples were lysed overnight in standard proteinase K buffer and then purified by bead extraction using the Biorobot M48 system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA samples were resuspended and DNA concentration determined by picogreen analysis (SpectraMax XPS, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Purified DNA samples were analyzed utilizing the Murine Medium Density Linkage Panel (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) using the manufacturer’s standard protocol. Briefly, 250 ng of purified DNA was subjugated to analysis and then loaded onto 32 sample beadchips. Beadchips were assayed on the Illumina Beadarray reader and then analyzed using the manufacturer’s software. Resultant data were imported into Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) for manual correction of implausible recombinations, poor clustering of alleles, and other evidence of bad marker performance. The file was then formatted for input to R/QTL. Of the 1,449 SNPs on the LD panel, 880 (61%) differed between the parental strains and were thus informative. Of these, 878 (99.7%) gave the expected call with parental control DNA. In addition, two samples (Nos. 23 and 141) were repeated in independent experiments and were shown to demonstrate >99% identity of allele calls between the two separate analytical runs.

QTL mapping

QTL mapping was performed using the R/QTL package (Broman et al. 2003; Manichaikul et al. 2009). Six phenotypic measures were subject to QTL analysis: rotarod baseline, rotarod learning, rotarod ataxia, hypothermia, LORR, and BECs at LORR recovery. In each case, a main-effects (single-locus) scan was first applied to find suggestive and significant main effects. Additive and interacting sex co-factors were then analyzed to search for sex-specific loci. Each single-locus scan of autosomes was subject to 1,000 permutations, with a separate permutation for the X chromosome to determine significance thresholds. Finally, a pairwise QTL scan, which included additive and interacting cofactors, was performed with 250 permutations. Suggestive main-effects loci (P < 0.63) and suggestive pairwise loci (full model P < 0.63) were included in a multiple-QTL model, which included an additive and fully interacting effect of sex. The models were reduced by backward elimination using the stay criterion of P < 0.05 for each term.

The 1.5-LOD confidence interval was identified using R/QTLs lodint function. QTLs for other alcohol-related measures were found by querying the Mouse Genome Database (MGD) for any QTLs within this confidence interval. All positional candidates for loci mapped in the present study and those found in the MGD were imported into the GeneWeaver software system (Baker et al. 2011), which enables discovery of hierarchical intersections among gene set-centered data. We compared positional candidates with other functional genomics data sets, including 39 sets of genes from differential expression and coexpression studies, using GeneWeaver’s “PhenomeMap” function. This enabled us to identify high-order intersections among gene sets, including the set of QTL positional candidates at a given locus.

Results

Parental strain dose-response comparison

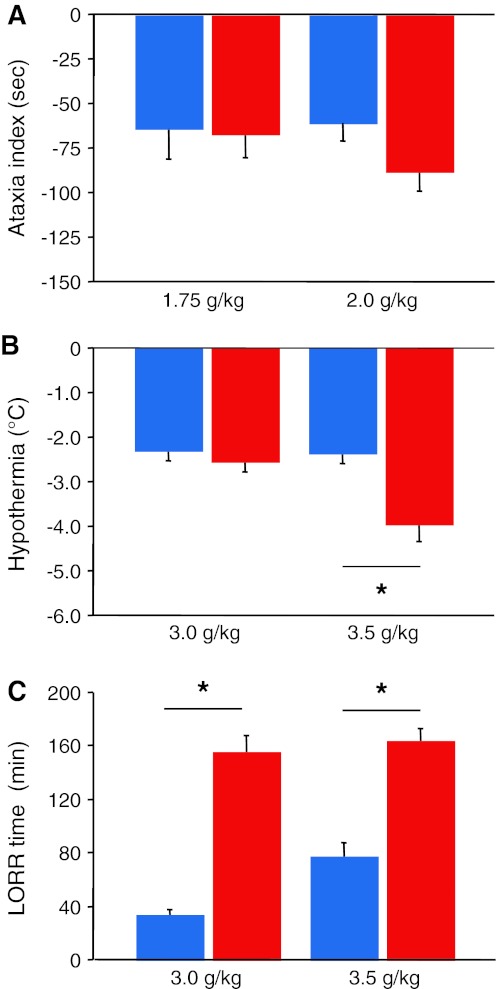

B6 and S1 did not significantly differ in the average rotarod training latency or changes in latency across training trials (data not shown). Strain comparison also found no significant effect of strain or EtOH dose (or interaction between the two) for ataxia responses to 1.75 or 2.0 g/kg EtOH (Fig. 1a). For hypothermia responses, there was a significant interaction between strain and EtOH dose (F 1,28 = 5.46, P < 0.05, n = 8/strain/dose). Fisher’s post-hoc tests showed that S1 had a significantly greater hypothermia response than B6 to the 3.5-g/kg but not to the 3.0-g/kg dose (Fig 1b). For LORR, there was also a significant main effect of strain (F 1,28 = 123.49, P < 0.01, n = 8/strain/dose) and EtOH dose (F 1,28 = 7.57, P < 0.01) and near significant interaction between the two (F 1,28 = 3.77, P = 0.062). Fisher’s post-hoc tests showed that S1 had significantly longer LORR than B6 to the 3.0- and 3.5-g/kg doses (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Trait differences between parental strains. a S1 (red bars) and B6 (blue bars) mice did not differ in ataxia responses to either 1.75 or 2.0 g/kg EtOH. b S1 had a significantly greater hypothermia response than B6 to a 3.5- but not a 3.0-g/kg EtOH dose. c S1 had significantly longer LORR responses than B6 to either a 3.0- or a 3.5-g/kg EtOH dose. *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM (colour figure online)

In a separate cohort tested for EtOH clearance, there was a significant main effect of time point on BECs (F 3,33 = 21.51, P < 0.01), but not strain or strain × time interaction, indicating an absence of strain differences and a reduction in BEC values across time points (5 min: S1 = 389 ± 16, B6 = 339 ± 38; 30 min: S1 = 372 ± 18, B6 = 336 ± 18; 60 min: S1 = 306 ± 19, B6 = 299 ± 19; 240 min: S1 = 243 ± 16, B6 = 239 ± 21; n = 6–7 per strain).

F2 phenotype and QTL analysis

Significant or suggestive QTLs were detected and multi-locus models identified for each trait (Table 1). The 1.5 LOD confidence interval was determined for each locus (Table 2).

Table 1.

Multiple QTL models

| Trait | Effect | Peak marker | LOD | %Variance | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothermia | ||||||

| 3@80.2 | rs3710548 | 3.607 | 4.272 | 4.131 | 0.002788 | |

| 7@18.4 | rs13479153 | 2.561 | 3.011 | 5.824 | 0.003261 | |

| 16@30.9 | rs4182243 | 2.708 | 3.188 | 6.166 | 0.002345 | |

| Sex | 4.167 | 4.953 | 6.387 | 0.000321 | ||

| 3@80.2:sex | 3.039 | 3.586 | 6.935 | 0.001119 | ||

| LORR | ||||||

| Sex | 24.293 | 25.7219 | 8.0809 | 2.55E − 15 | ||

| 2@21.4 | rs13476399 | 6.785 | 6.3172 | 2.4808 | 0.00417 | |

| 4@93.4 | rs3695715 | 3.255 | 2.9549 | 3.4812 | 0.00849 | |

| 8@22.5 | rs3666140 | 3.595 | 3.2715 | 3.8542 | 0.00454 | |

| 12@31.0 | rs6344105 | 8.0043 | 7.5183 | 2.9525 | 0.00067 | |

| 19@33.8 | rs6194426 | 2.6302 | 2.3771 | 2.8005 | 0.02621 | |

| sex:2@21.4 | 5.2937 | 4.8763 | 3.8299 | 0.00108 | ||

| sex:4@93.4 | 0.4142 | 0.3685 | 0.8682 | 0.42076 | ||

| sex:8@22.5 | 3.3885 | 3.079 | 7.2548 | 0.00084 | ||

| sex:12@31.0 | 4.6929 | 4.3043 | 3.3806 | 0.00307 | ||

| sex:19@33.8 | 2.432 | 2.1948 | 5.1715 | 0.0062 | ||

| 2@21.4:12@31.0 | 5.2204 | 4.8062 | 2.8311 | 0.00484 | ||

| sex:2@21.4:12@31.0 | 4.3595 | 3.9889 | 4.6994 | 0.00109 | ||

| BECs | ||||||

| Sex | 2.39 | 2.889 | 3.571 | 0.014446 | ||

| 7@6.3 | rs13479145 | 4.899 | 6.029 | 3.726 | 0.001361 | |

| 9@11.6 | rs13480854 | 4.002 | 4.893 | 4.535 | 0.001422 | |

| 11@2.6 | rs3697686 | 5.317 | 6.563 | 4.056 | 0.000626 | |

| sex:9@11.6 | 1.515 | 1.819 | 3.373 | 0.035568 | ||

| 7@6.3:11@2.6 | 2.58 | 3.122 | 2.894 | 0.022406 | ||

| Rotarod averagea | ||||||

| Sex | 3.336 | 3.379 | 4.965 | 0.002203 | ||

| 1@92.7 | rs3700831 | 2.241 | 2.253 | 4.966 | 0.007503 | |

| 4@9.0 | rs13477617 | 3.774 | 3.834 | 8.45 | 0.000264 | |

| 5@2.8 | rs13478110 | 3.398 | 3.443 | 3.794 | 0.004952 | |

| 6@48.2 | rs6239023 | 3.74 | 3.798 | 8.37 | 0.000285 | |

| 7@48.4 | mCV23423763 | 2.633 | 2.655 | 5.85 | 0.003187 | |

| 12@64.5 | rs13481614 | 2.238 | 2.25 | 4.959 | 0.007556 | |

| 18@56.2 | rs4137441 | 1.879 | 1.884 | 4.153 | 0.016549 | |

| sex:5@2.8 | 3.335 | 3.378 | 7.445 | 0.000688 | ||

| Training index | ||||||

| 11@42.4 | rs13481076 | 3.417 | 4.434 | 0.000409 | ||

| Ataxia | ||||||

| sex | 0.9151 | 0.9477 | 3.898 | 0.049212 | ||

| 8@39.7 | rs3699406 | 9.6403 | 10.586 | 2.419 | 0.001172 | |

| 9@44.0 | rs3655717 | 10.2343 | 11.2837 | 2.578 | 0.000506 | |

| 17@20.2 | rs3672987 | 11.406 | 12.676 | 2.896 | 9.05E-05 | |

| 8@39.7:9@44.0 | 4.4048 | 4.6692 | 1.6 | 0.090041 | ||

| 8@39.7:17@20.2 | 6.0238 | 6.4552 | 2.212 | 0.011097 | ||

| 9@44.0:17@20.2 | 6.7097 | 7.2235 | 2.476 | 0.004152 | ||

| 8@39.7:9@44.0:17@20.2 | 3.9876 | 4.2152 | 2.167 | 0.029703 | ||

Effect sizes for the peak marker(s), LOD scores, F statistic, and degrees of freedom are given for dropping each term from the model

aDue to the large number of loci in the model, multilocus interactions were not tested extensively

Table 2.

Proportional hazards mapping for censored trait data

| Trait | Marker | Chr | Position (Mb) | LOD | LOD P | LOD Pμ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotarod averagea | rs6239023 | 6 | 94.005991 | 4.03334 | 0.266541 | 3.766629 |

| rs4226783 | 7 | 100.081465 | 3.820091 | 0.691785 | 3.129 | |

| rs3719581 | 11 | 86.772383 | 4.824871 | 0.251099 | 4.573533 | |

| rs3702256 | X | 131.483758 | 3.133643 | 0.336518 | 2.796845 | |

| LORR | rs6268364 | 4 | 151.390225 | 5.74 | 4.853 | 0.884 |

| rs3718735 | 6 | 101072507 | 3.95 | 1.287 | 2.665 |

aDue to the censored data distribution, multilocus interactions were not tested extensively

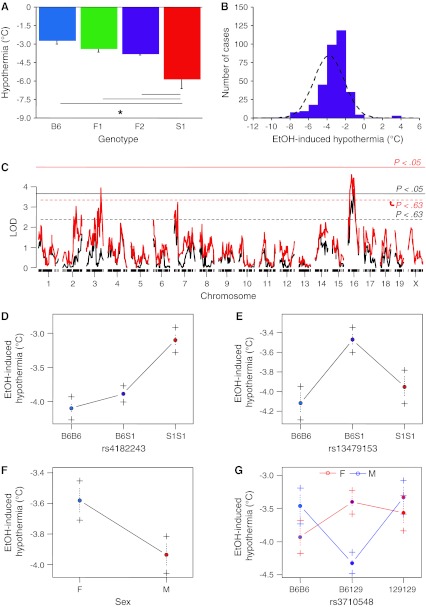

EtOH-induced hypothermia

Comparison of the B6, S1, F1, and F2 population means revealed differences in hypothermia (F 3,368 = 62.42, P < 0.01, n = 8–345). Fisher’s post-hoc tests revealed that hypothermia in S1 was greater than that in the three other genotypes (which did not differ from each other) (Fig. 2a). F2 hypothermia scores were quite narrowly distributed around approximately –3°C (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

EtOH-induced hypothermia. a S1 had a greater EtOH-induced hypothermia response than B6, F1, and F2. b Frequency histogram showing approximately normal distribution (dashed line is normal distribution) in the F2 population. c A scan for single-locus main effects found a significant locus on Chr 16 (not shown), which was also detected using additive (black LOD trace) and interacting (red LOD trace) sex covariates, though the effect was merely suggestive with a covariate in the model. Additional loci were found on Chr 7 with an additive sex covariate and on Chr 3 with an interacting sex covariate. The empirical significance threshold P < 0.05 for the scan with an additive sex covariate is indicated by a solid black line. Suggestive thresholds are indicated by dashed lines for the additive sex covariate (black) and interacting sex covariate (red). d Allelic effects for the loci are consistent with a negative dominance deviation of the Chr 16 locus (rs4182243), whereas the Chr 7 locus (rs13479153) is overdominant, and the effects of Chr 3 (rs3710548) are sex dependent such that male heterozygotes have greater hypothermia than homozygotes of either sex and female heterozygotes have less hypothermia. Overall, in the F2 population males had greater EtOH-induced hypothermia scores than females (note that data obtained in the parental lines were from males only, precluding direct comparison with this QTL effect); *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM (colour figure online)

QTL analysis and multilocus modeling (Table 1) revealed two significant main-effect loci (P < 0.05), as well as a significant sex effect and a third main-effect locus that interacted with sex (Fig. 2c). The first locus was on Chromosome (Chr) 16 at 30.9 cM (LOD = 3.9, P < 0.05), with a peak marker at rs4182243 and a 1.5-LOD drop confidence interval from rs4165065 (8.13 cM) to rs4200124 (40.0 cM) that was independent of sex (Fig. 2d). A second locus was detectable with an additive sex effect in the model on Chr 7 at 18.4 cM, with a peak marker at rs13479153 (LOD = 2.8, P < 0.01) (Fig. 2e). The third locus, detectable with additive and interacting effects of sex, was found on Chr 3 at 80.2 cM, with a peak marker at rs3710548 (LOD = 3.9, P < 0.6) (Fig. 2f, g). Multilocus modeling revealed that together the loci and their interactions accounted for 13.1% of the variance in EtOH-induced hypothermia (Table 1).

EtOH-induced LORR and BECs at recovery

Comparison of the B6, S1, F1, and F2 population trait means found differences in loss of righting reflex (LORR) time (F 3,350 = 9.44, P < 0.01, n = 8–327). Fisher’s post-hoc tests revealed that LORR time in S1 was greater than that in the three other genotypes and greater in F2 than in B6 (Fig. 3a). F2 LORR scores were somewhat bimodally distributed, with many values around approximately 60 min and another cluster around the cutoff of 180 min (Fig. 3b). Forty-five F2 mice, representing 12% of the cases, reached the cutoff LORR duration of 180 min.

Fig. 3.

EtOH-induced LORR. a EtOH-induced LORR in S1 was greater than that in B6, F1, or F2, and greater in F2 than that in B6. b F2 LORR scores were somewhat bimodally distributed (dashed line is normal distribution), with many values around 60 min and another cluster around the cutoff of 180 min. c A scan for single-locus main effects using the two-part model found a significant main-effect locus on Chr 4 and a suggestive locus on Chr 6. d The locus has an S1 dominant effect. e Regression revealed a sex difference in the allelic effect of this locus such that males with the S1 alleles had the highest LORR duration; *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM

QTL analysis of LORR required R/QTL’s two-part (proportional hazards) model to account for right-censored phenotypic data (Table 3). This analysis revealed a significant main-effect locus on Chr 4 at 93.4 cM (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3c). The Chr 4 locus had a dominant S1 effect (Fig. 3d). The combined LOD for this locus was 5.74 (P < 0.05), with a LOD for the proportion censored of 4.853 (P < 0.05) and a LOD for the mean difference between genotypes of 0.884 (nonsignificant). A suggestive locus was also detected on Chr 6 at 52.6 cM. The combined LOD for this locus was 3.95 (P < 0.63), with a LOD for the mean difference between genotype classes at 2.665 (P < 0.63) and a LOD for the difference between proportion censored of 1.287 (nonsignificant). Sex effects and multilocus modeling could be evaluated using only conventional parametric methods in the R/QTL environment, and these results must be interpreted cautiously. The effect of the QTL, which would be downwardly biased in parametric analysis, accounted for 4.8% of the variance in LORR duration. Many suggestive loci and interactions were detected using parametric methods, including a sex interaction with the Chr 4 locus such that males with the S1 alleles had a higher LORR time (Fig. 3e).

Table 3.

Locations of QTL 1.5 LOD confidence intervals

| Peak | Right of peak | Left of peak | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | Marker | Position (Mb) | Flanking | Position (cM) | Position (Mb) | Flanking | Position (cM) | Position (Mb) |

| Hypothermia | ||||||||

| 3 | rs3710548 | 145932289 | rs3719390 | 43.56103 | 85222358 | rs30801216 | 92.92514 | 156802752 |

| 7 | rs13479153 | 25722935 | rs3700068 | 0 | 4187548 | rs3716088 | 103.14114 | 140189839 |

| 16 | rs4182243 | 46052770 | rs4165065 | 8.129282 | 17412172 | rs4200124 | 40.029943 | 70695141 |

| LORR (normal model) | ||||||||

| 2 | rs13476399 | 28144658 | rs3713997 | 0 | 3151175 | rs3679483 | 104.33488 | 179861211 |

| 4 | rs3695715 | 3649824 | rs3663950 | 71.81746 | 135285447 | rs6279100 | 103.79191 | 155557887 |

| 8 | rs3666140 | 44049661 | rs3661760 | 8.001332 | 24557766 | rs13479995 | 64.990121 | 116236688 |

| 12 | rs6344105 | 68860209 | rs3706319 | 26.52421 | 59053677 | rs13481604 | 61.30464 | 99317323 |

| 19 | rs6194426 | 50203520 | rs13483643 | 27.73783 | 45386221 | rs13483682 | 38.33064 | 55236132 |

| LORR (2-part model) | ||||||||

| 4 | rs6268364 | 151390225 | rs3663950 | 71.81746 | 135285447 | rs13478068 | 100.53031 | 154592281 |

| 6 | rs3718735 | 101072507 | rs13478783 | 33.2687 | 60541373 | rs6200835 | 68.78922 | 125667502 |

| BECs | ||||||||

| 7 | rs13479145 | 19988355 | rs6384973 | 1.031631 | 5036805 | rs3663313 | 49.842558 | 63388111 |

| 9 | rs13480854 | 7524005 | mCV23893269 | 0 | 4062079 | rs6304156 | 85.96028 | 123063108 |

| 11 | rs3697686 | 58381052 | rs13480836 | 0 | 3454200 | rs3697686 | 35.406444 | 58381052 |

| Rotarod average | ||||||||

| 1 | rs3700831 | 177945647 | rs6312657 | 39.70795 | 69048455 | rs13476300 | 109.1582 | 192122502 |

| 4 | rs13477617 | 26886337 | rs3660863 | 2.380086 | 7127435 | rs3684104 | 23.498602 | 38269953 |

| 5 | rs13478110 | 9741228 | rs13478092 | 0 | 3595407 | rs3718776 | 98.87341 | 150393227 |

| 6 | rs6239023 | 94005991 | rs3672029 | 38.74415 | 75345665 | rs30316697 | 71.27386 | 130188177 |

| 7 | mCV23423763 | 68111945 | rs3700068 | 0 | 4187548 | rs3663988 | 114.24183 | 146505067 |

| 12 | rs13481614 | 102385663 | rs33846822 | 9.596159 | 30605487 | rs29187760 | 78.763939 | 115166913 |

| 18 | rs4137441 | 88803388 | rs13483426 | 38.08931 | 70283358 | rs4137441 | 56.24318 | 88803388 |

| Training index | ||||||||

| 11 | rs13481076 | 66532354 | rs3697686 | 35.40644 | 58381052 | rs3688955 | 60.98294 | 90397849 |

| Ataxia | ||||||||

| 8 | rs3699406 | 72486070 | rs6386110 | 26.80781 | 45897379 | rs13479995 | 64.99012 | 116236688 |

| 9 | rs3655717 | 65312971 | rs13480112 | 12.57837 | 26413932 | rs13480421 | 71.20274 | 111761261 |

| 17 | rs3672987 | 33247165 | rs4136382 | 0 | 3388912 | rs3715723 | 32.7513 | 58810428 |

Physical and genetic locations of the peak marker and flanking markers around the QTL confidence interval, determined by analysis of the one-way scan. For multiple-locus effects, locations are influenced by the other terms in the model and in some cases cannot be readily determined. A large interval should be considered for follow-up studies

There was no significant difference in population means for BECs at LORR recovery (n = 6–305). Planned post-hoc tests revealed that BECs were higher in B6 than in F2 (Fig. 4a). BECs in the F2 population were normally distributed around approximately 350 mg/dl (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

BECs at LORR recovery. a BECs at LORR recovery were higher in B6 than in F2. b Frequency histogram showing largely normal distribution (dashed line is normal distribution) in the F2 population. c A scan for single-locus main effects found two suggestive loci (P < 0.63, dashed black line), and a scan for single-locus sex interactions found another suggestive locus on Chr 9. d–g Allelic effects of the main-effect loci reveal under dominance on Chr 7 and a slightly positive dominance deviation on Chr 11. The sex difference is such that males had a lower LORR BEC than females, with male S1 homozygotes having the lowest LORR BEC; *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM

A one-way scan revealed two suggestive main-effect loci for this trait (Fig. 4c). The first locus was on Chr 7 (Fig. 4d) and the second on Chr 11 (Fig. 4e). These loci interacted statistically with each other but not with sex (Fig. 4f). A third locus on Chr 9 was found to interact with sex (Fig. 4c, g). Multilocus modeling estimated that together the loci account for 16.9% of the total phenotypic variance.

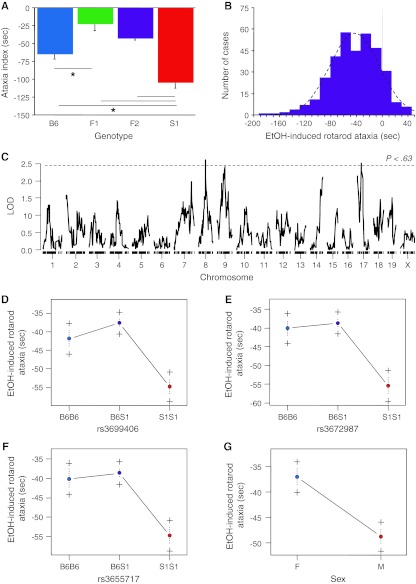

Motor coordination, learning, and EtOH-induced ataxia

Comparison of the B6, S1, F1, and F2 population means found differences in the average latency to fall across ten trials of rotarod training (F 3,351 = 2.52, P < 0.01, n = 8–328). Fisher’s post-hoc tests revealed that scores were higher in B6 than in the three other genotypes, while S1 scores were higher than those in F2 (Supplementary Fig. 1A). A frequency histogram of the F2 population indicated a largely normal distribution (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Multiple significant and suggestive main-effect loci were found using a main-effect scan (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1C–I), one of which (peak marker rs13478110) interacted with sex (Supplementary Fig. 1J, K). There was also a sex-specific locus on Chr 5 (Supplementary Fig. 1L). These loci were all retained in multiple-locus modeling, together accounting for 25% of phenotypic variance. No higher-order interactions were tested to avoid overfitting the model.

For the rotarod training index there was a trend toward a significant difference in B6, S1, F1, and F2 population means (F 3,369 = 2.36, P = 0.072, n = 8–346). Planned comparisons post-hoc revealed that S1 showed a greater improvement with training than F1 and F2 (Supplementary Fig. 2A). A frequency histogram of the F2 population indicated a normal distribution, with the majority of scores around 50 s (Supplementary Fig. 2B). A single suggestive main-effect QTL was found (Supplementary Fig. 2C) on Chr 11 at 42 cM (peak marker rs13481076), which accounted for 4.4% of the phenotypic variance.

Finally, comparison of the B6, S1, F1, and F2 population means found a significant difference in the EtOH-induced rotarod ataxia index (F 3,369 = 8.96, P < 0.01, n = 8–346). Fisher’s post-hoc tests revealed that ataxia was greater in S1 than in the other three genotypes and greater in B6 than in F1 (Fig. 5a). F2 ataxia scores were normally distributed around approximately −40 s (Fig. 5B). QTL analysis found three suggestive loci on Chrs 8, 9, and 17 from the main-effect scan (Table 1; Fig. 5c–e). Additional scans and multilocus modeling revealed a main effect of sex (Fig. 5f) and several interactions among the loci, including a three-way interaction (not shown). The main effects of the three loci together accounted for 12.4% of the variance in this phenotype and have allelic effects that mimic the parental differences. Taken together, the sex effects, main effects, and interactions among loci accounted for 22.4% of the phenotypic variance.

Fig. 5.

EtOH-induced rotarod ataxia. a S1 had a higher-magnitude ataxia index (change in latency to fall from pre-EtOH to post-EtOH trials) than B6, F2, and F1, and B6 had a higher index than F1. b Frequency histogram illustrates normal distribution (dashed line is normal distribution) of training index scores in the F2 population. c A scan for single-locus main effects found three suggestive loci at genome-wide P < 0.63. d–g Main effects of the loci and sex difference, each of which revealed a dominant effect of the B6 allele; *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM

Trait correlations in the F2 population

Table 4 summarizes correlations between phenotypic measures in the F2 population. There were significant, Bonferroni-corrected, negative correlations between average baseline rotarod training latency and EtOH-induced ataxia, between EtOH-induced ataxia and LORR duration, and between LORR duration and BECs at LORR recovery.

Table 4.

Phenotypic correlations in F2 mice

| Training index | Ataxia | Hypothermia | LORR | BECs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotarod average | +0.13 | −0.20* | +0.02 | −0.16 | +0.07 |

| Training index | – | −0.15 | +0.05 | −0.01 | −0.06 |

| Ataxia | – | – | +0.04 | −0.33* | −0.06 |

| Hypothermia | – | – | – | −0.12 | +0.09 |

| LORR | – | – | – | – | −0.24* |

There were significant negative correlations between average baseline rotarod latency and rotarod ataxia, between EtOH-induced rotarod ataxia and LORR duration, and between LORR duration and blood EtOH concentrations (BECs) at LORR recovery

* Bonferroni corrected (P < 0.001) significance

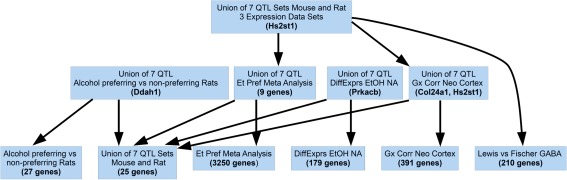

Integrative functional genomics

Several overlapping QTLs were identified among loci in our study and those previously reported in the Mouse Genome Database (Supplementary Table 1). The Chr 3 QTL for EtOH-induced hypothermia overlaps four previously observed QTLs for alcohol preference and consumption. GeneWeaver analysis of these overlapping loci and related data from several functional genomics experiments (Fig. 6) reveals Hs2st1 as the most highly connected candidate.

Fig. 6.

Candidate genes for Chr 3 hypothermia from integrative functional genomics. Hierarchical intersections of functional genomic data with positional candidate genes at six loci that overlap the Chr 3 EtOH hypothermia locus, including four mouse loci and two syntenic loci mapped in rat, were generated using the GeneWeaver Phenome Graph function. Terminal nodes represent individual sets of positional candidate genes and published differential expression or coexpression gene sets. Higher-order nodes represent two-way, three-way, and higher-order intersections of these sets, respectively. Genes in the highest nodes are connected to the largest number of gene sets and are thus considered more highly supported candidates by empirical evidence. The six QTLs that overlap with the Chr 3 hypothermia QTL are Alcp3 (Peirce et al. 1998), Ap6q (Tarantino et al. 1998), Letohc1 (Belknap and Atkins 2001), Lore10 (Bennett et al. 2006) from mouse and Alcrsp17 (Radcliffe et al. 2006) and Alcrsp28 (Radcliffe et al. 2009) from rat. The gene expression sets that intersect with positional candidates from the QTL interval are ‘GS128167: Lewis vs. Fischer GABA’ (Sharp et al. 2011) with differential expression in the nucleus accumbens (NA) shell GABA neurons projecting to ventral pallidum in these two strains, ‘GS31783: Gx Corr Neo Cortex’ (Phillips et al. 1994) where the gene expression in BXD Neocortex ILM6v1.1 (Feb08) RankInv microarray data from GeneNetwork.org was correlated with preference for 10% ethanol (g/kg) in a two-bottle choice, ‘GS3647: Et Pref Meta Analysis’ (Mulligan et al. 2006) consisting of genes from the meta-analysis of differential expression in six isogenic and three selected lines with elevated voluntary ethanol consumption, ‘GS87303: Alcohol preferring vs. non-preferring Rats’ (Edenberg et al. 2005) consisting of differential expression in the hippocampus of inbred alcohol-preferring (iP) and -nonpreferring (iNP) rats, and ‘GS128167: DiffExprs EtOH NA’ (Rodd et al. 2008) consisting of differential expression in the NA of inbred alcohol-preferring mice

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to identify QTLs underlying variation in sensitivity to alcohol intoxication in a F2 B6 × S1 population. We detected a number of loci influencing a set of complex, polygenic phenotypic measures, which in several cases interacted with sex.

The current study was based upon previous observations that the S1 parental strain was significantly more sensitive to the sedative/hypnotic, but not the ataxic or hypothermic, effects of a 3-g/kg dose of EtOH than the B6 parental strain (Chen and Holmes 2009; Palachick et al. 2008; L. DeBrouse et al. (unpublished)). Here, we replicated this difference and further found that a higher EtOH dose (3.5 g/kg) produced not only a greater sedative/hypnotic response but also a greater hypothermic response in S1 compared to B6 mice. We also found that while the strains showed an equivalent ataxic response to a 1.75-g/kg EtOH dose, S1 mice showed modestly greater ataxia to a 2.0-g/kg EtOH dose than B6 that was statistically significant in only one of two experiments. Previous studies using variations on these methods have generally found similar results, including some inconsistency in ataxia measures, in the context of larger inbred strain panels (Crabbe et al. 2003a, b, 2005; Metten et al. 2004; Rustay et al. 2003). Thus, these data confirm our earlier observations that S1 mice are more sensitive to acute EtOH challenge than B6 mice, and extend them by demonstrating that the strains differ across a broader range of measures at increasing EtOH doses.

It is important to note that the current study was conducted in mice that had previously been assessed for Pavlovian fear conditioning and extinction (results to be presented in a future article). To minimize potential carry-over effects, an interval of at least 1 week was interposed between the completion of fear testing and the start of EtOH testing. However, the possibility remains that by virtue of its stressful nature, prior fear testing impacted measures of sensitivity. Discounting, but not fully excluding this possibility, we have previously shown that while sensitivity to EtOH-induced hypothermia and LORR duration was increased in B6 mice by exposure to chronic (14 days) swim stress that ended the day prior to testing, neither acute (1 day) nor subchronic (3 days) stress was sufficient to alter these measures (Boyce-Rustay et al. 2007, 2008a).

The measures of EtOH sensitivity used in the current study cannot dissociate between the initial response to EtOH challenge and acute functional tolerance (AFT) to that response. AFT has a strong genetic component (for review, see Tabakoff et al. 2008). Prior work has shown that S1 mice have a similar AFT as that of B6 to LORR duration (Ponomarev and Crabbe 2004), but have a greater AFT to EtOH-induced ataxia in the rotarod (Rustay and Crabbe 2004) and dowel test (Hu et al. 2008). Greater AFT would be expected to be associated with a decreased, not increased, sensitivity which is opposite to that shown by S1; these data suggest that AFT is unlikely to explain the strain differences. However, more direct examination of AFT in our assays would be necessary to fully exclude a contribution of this process.

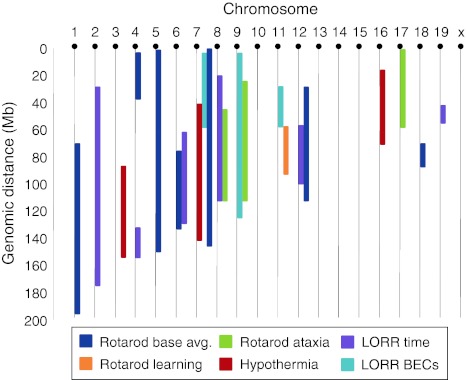

QTL analysis was conducted on all three measures of behavioral intoxication as well as pre-EtOH baseline rotarod and motor learning (summarized in Fig. 7). We have the greatest confidence in the QTLs for hypothermia and LORR, which were apparent in a simple main-effect scan. These were found on Chr 16 for hypothermia and on Chrs 4 and 6 for LORR. These QTLs were of generally small effect. While this is typical for QTLs for behavioral traits, it does suggest a significant nongenetic source of variance and/or a degree of insensitivity of our mapping analysis. Nonetheless, the hypothermia and LORR QTLs may be amenable to refinement (e.g., with introgressed-congenic strategies) and experimental validation (e.g., via building convergent evidence across studies), although this will be complicated by our finding that these phenotypes also showed main effects (hypothermia) or interactions (LORR) with sex.

Fig. 7.

Summary schematic of QTL identified in the current study. QTLs in multilocus models for each phenotype are shown (see key). The bar length corresponds to the 1.5-LOD confidence interval for each phenotype

Our analysis revealed a number of other QTLs that overlap with those previously linked to EtOH-related phenotypes in various mouse populations. For example, a query of the MGD revealed that the hypothermia QTL we found on Chr 7 overlaps Ethm3 (Crawshaw et al. 2001) and our Chr 2 locus for LORR overlaps with Alcrsp2 (Erwin et al. 1997). In addition, the Chr 16 hypothermia QTL we found overlaps with that previously linked to similar phenotypes in other mouse populations. This QTL is in the same region as a LORR QTL (Browman and Crabbe 2000) and EtOH drinking phenotype QTL (Gehle and Erwin 1998) previously found in B6 × DBA/2J recombinant inbreds (BXD RI). Interestingly, this same locus has been recently linked to a measure of EtOH AFT in long-sleep/short-sleep mice (Bennett et al. 2007) and EtOH drinking in a B6 × C3H/HeJ F2 population (Drews et al. 2010).

Of the other QTLs we found, loci for BEC at LORR recovery on Chrs 9 and 11 overlap with a number of preference-related loci (Bachmanov et al. 2002; Bice et al. 2006; Erwin et al. 1997; Malmanger et al. 2006; Melo et al. 1996; Phillips et al. 1994; Tarantino et al. 1998), and the Chr 9 locus also overlaps with loci for acute alcohol locomotor activation (Erwin et al. 1997; Malmanger et al. 2006) and conditioned taste aversion (Risinger et al. 1998) and our locus for ataxia. The other locus we found for ataxia on Chr 8 does not overlap any previously discovered alcohol-related loci, but interestingly, it does overlap Cbm2, a QTL for cerebellum weight (Airey et al. 2001). Likewise, our QTLs for LORR overlap with alcohol-drinking loci on Chrs 2, 4, 8, and 12 (Bachmanov et al. 2002; Belknap et al. 1997; Bice et al. 2006; Fernandez et al. 1999; Gill and Boyle 2005; Melo et al. 1996; Phillips et al. 1994; Tarantino et al. 1998). Also of particular note is the large number of traits that we found to map to Chr 2, given previous reports that a locus in this region has been linked to various EtOH-related traits in various mouse lines (Crabbe et al. 1994; Gill and Boyle 2005; Malmanger et al. 2006). Candidate gene studies implicate Stxbp1 as a candidate for consumption-related traits at this locus (Fehr et al. 2005). More broadly, the finding that our LORR QTL overlapped with regions consistently linked to EtOH drinking suggests a common genetic influence on these behaviors. This provides important, albeit indirect, evidence supporting the hypothesis that variation in sensitivity to high-dose (aversive) EtOH intoxication is a factor driving the propensity to drink and, by extension, relative risk for alcohol abuse (Krystal et al. 2003).

The convergent loci across studies could facilitate the reduction of positional candidates using a multiple-cross mapping strategy or other comparison of strain haplotypes, or through the integration of other functional studies. For this reason, we have deposited all QTL positional candidates into the GeneWeaver database (Baker et al. 2011). Using this system, we have identified priority candidates for the Chr 3 EtOH-induced hypothermia locus that may influence multiple EtOH-related responses. The most highly connected candidate is Hs2st1, a heparin sulfate sulfotransferase. A search of the Allen Brain Atlas reveals that this gene is highly expressed in the hippocampus. A GeneNetwork query reveals that it is coexpressed with alcohol preference in BXD RI strains. Another compelling candidate is Prkacb, interesting because of the already known role of the protein kinase A pathway in both LORR and hypothermia (Yang et al. 2003).

There are several instances where our data do not correspond to prior studies. For example, with the exception of QTLs on Chr 6 previously found for ethanol consumption in a B6.BALB/cJ-introgressed line (Vadasz et al. 2007) and for ethanol-induced locomotor activity (Downing et al. 2003), the LORR QTLs we report are largely distinct from those reported for LORR duration in BXD RI (Browman and Crabbe 2000), LXS (Haughey et al. 2005), and long-sleep/short-sleep mice (Bennett et al. 2002, 2008) populations, EtOH drinking in BXDs (Phillips et al. 1998), as well as EtOH drinking (Belknap et al. 1997; McClearn et al. 1997) and EtOH-induced locomotor stimulation in a B6 × D2 intercross (Hitzemann et al. 1998).

QTL mapping studies rarely have sufficient power to reveal all causative loci underlying complex phenotypes, and in our study we also failed to reproduce the QTL on a Chr 1 “hotspot” previously linked to multiple EtOH phenotypes in other mouse crosses (Ehlers et al. 2010; Mozhui et al. 2008). These situations could be the result of differences in segregating alleles in each of these populations and heterozygosity in our B6 × S1 F2 population, methodological differences in the measurement of EtOH-related phenotypes between studies, or simply genuine false negatives. Although we performed genome-wide searches, it is computationally prohibitive to search the entire multiple-locus model space. Future studies using alternative statistical QTL models may have better fidelity. It will also be important to take some of our provisional findings further by testing for convergent evidence from other crosses.

A consistent finding in the QTL–EtOH literature that was also a major pattern in our data is the largely nonoverlapping QTLs across phenotypes (e.g., see Browman and Crabbe 2000; Drews et al. 2010; Gehle and Erwin 1998; Phillips et al. 1998). This was echoed by our phenotypic correlational analysis, which found few significant correlations between phenotypes. One exception was a significant negative correlation between ataxia and LORR, indicating that high sensitivity to EtOH’s ataxic effects predicted high sensitivity to LORR. Longer LORR time was also associated with lower BECs on awakening. This is a general relationship and is not unexpected if LORR duration is a function of EtOH clearance as opposed to being modulated independently of LORR time by, for example, pharmacokinetic factors. Nonetheless, both measures can provide useful measures of EtOH sensitivity and are best considered together. The more general conclusion from these correlational analyses across the various end-point measures we made is that the pattern of largely noncorrelations is consistent with largely independent genetic influences.

In conclusion, the current study found a number of genomic locations associated with three different behavioral measures of EtOH intoxication. The most compelling QTLs were identified for hypothermia and LORR, with provisional QTLs found for ataxia. The hypothermia and LORR QTLs were found at separate genomic regions, suggesting predominantly distinct genetic contributions to these measures of intoxication. Current data provide a basis for further studies, which by utilizing sequence data, gene expression repositories, QTL archives, and integrative functional genomic tools could identify specific polymorphisms within these QTLs. In the longer term, uncovering the candidate genes associated with variation in these phenotypes in this mouse population could provide novel insight into genetic factors that might also underlie sensitivity to the negative feelings of EtOH intoxication in humans.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. 1 Average rotarod training latency. A S1 and F2 had a lower latency to fall than B6. B Frequency histogram illustrates normal distribution (dashed line is normal distribution) of training index scores in the F2 population. C A scan for single-locus main effects found several suggestive and significant loci (black) and a scan for sex-interacting loci found a locus on Chr 5. An additional locus on distal 7 may also interact with sex. D Effect plots for each of the main effects and a sex-interacting locus; *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM (EPS 1228 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2 Rotarod training index. A S1 had a higher training index (increase in latency to fall from training trial 1 to trial 10) than F2 or F1. B Frequency histogram illustrates normal distribution (dashed line is normal distribution) of training index scores in the F2 population. C A scan for single-locus main effects found a suggestive locus on Chr 11. D Effect plot for the peak locus on Chr 11; *p < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM (EPS 1111 kb)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Intramural Research Program (Z01 AA000411). EJC was supported by The Jackson Laboratory and R01 AA18776.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- Airey DC, Lu L, Williams RW. Genetic control of the mouse cerebellum: identification of quantitative trait loci modulating size and architecture. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5099–5109. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05099.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmanov AA, Reed DR, Li X, Li S, Beauchamp GK, Tordoff MG. Voluntary ethanol consumption by mice: genome-wide analysis of quantitative trait loci and their interactions in a C57BL/6ByJ × 129P3/J F2 intercross. Genome Res. 2002;12:1257–1268. doi: 10.1101/gr.129702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EJ, Jay JJ, Bubier JA, Langston MA, Chesler EJ. GeneWeaver: a web-based system for integrative functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:D1067–D1076. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Atkins AL. The replicability of QTLs for murine alcohol preference drinking behavior across eight independent studies. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:893–899. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-2074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Crabbe JC, Young ER. Voluntary consumption of ethanol in 15 inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112:503–510. doi: 10.1007/BF02244901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Richards SP, O’Toole LA, Helms ML, Phillips TJ. Short-term selective breeding as a tool for QTL mapping: ethanol preference drinking in mice. Behav Genet. 1997;27:55–66. doi: 10.1023/A:1025615409383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B, Beeson M, Gordon L, Johnson TE. Reciprocal congenics defining individual quantitative trait loci for sedative/hypnotic sensitivity to ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B, Carosone-Link P, Zahniser NR, Johnson TE. Confirmation and fine mapping of ethanol sensitivity quantitative trait loci, and candidate gene testing in the LXS recombinant inbred mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:299–307. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B, Downing C, Carosone-Link P, Ponicsan H, Ruf C, Johnson TE. Quantitative trait locus mapping for acute functional tolerance to ethanol in the L × S recombinant inbred panel. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:200–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B, Carosone-Link P, Beeson M, Gordon L, Phares-Zook N, Johnson TE. Genetic dissection of quantitative trait locus for ethanol sensitivity in long- and short-sleep mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:659–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bice PJ, Foroud T, Carr LG, Zhang L, Liu L, Grahame NJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Belknap JK. Identification of QTLs influencing alcohol preference in the high alcohol preferring (HAP) and low alcohol preferring (LAP) mouse lines. Behav Genet. 2006;36:248–260. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-9019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Rustay JM, Holmes A. Ethanol-related behaviors in mice lacking the NMDA receptor NR2A subunit. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:455–466. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Rustay JM, Cameron HA, Holmes A. Chronic swim stress alters sensitivity to acute behavioral effects of ethanol in mice. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Rustay JM, Janos AL, Holmes A. Effects of chronic swim stress on EtOH-related behaviors in C57BL/6J, DBA/2J and BALB/cByJ mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;186:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Rustay JM, Palachick B, Hefner K, Chen YC, Karlsson RM, Millstein RA, Harvey-White J, Holmes A. Desipramine potentiation of the acute depressant effects of ethanol: modulation by alpha2-adrenoreceptors and stress. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:889–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browman KE, Crabbe JC. Quantitative trait loci affecting ethanol sensitivity in BXD recombinant inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp M, Norcross M, Whittle N, Feyder M, D’Hanis W, Yilmazer-Hanke D, Singewald N, Holmes A. Impaired Pavlovian fear extinction is a common phenotype across genetic lineages of the 129 inbred mouse strain. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:744–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00519.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Holmes A. Effects of topiramate and other anti-glutamatergic drugs on the acute intoxicating actions of ethanol in mice: modulation by genetic strain and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1454–1466. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC. Sensitivity to ethanol in inbred mice: genotypic correlations among several behavioral responses. Behav Neurosci. 1983;97:280–289. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.97.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC (2007) Overview of Mouse Assays of Ethanol Intoxication. Current protocols in neuroscience. Wiley, New York [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crabbe JC, Belknap JK, Mitchell SR, Crawshaw LI. Quantitative trait loci mapping of genes that influence the sensitivity and tolerance to ethanol-induced hypothermia in BXD recombinant inbred mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:184–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Gallaher EJ, Crawshaw LI, Mitchell SR. Common genetic determinants of the ataxic and hypothermic effects of ethanol in BXD/Ty recombinant inbred mice: genetic correlations and quantitative trait loci. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:624–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Cotnam CJ, Cameron AJ, Schlumbohm JP, Rhodes JS, Metten P, Wahlsten D. Strain differences in three measures of ethanol intoxication in mice: the screen, dowel and grip strength tests. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:201–213. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183X.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Metten P, Yu CH, Schlumbohm JP, Cameron AJ, Wahlsten D. Genotypic differences in ethanol sensitivity in two tests of motor incoordination. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1338–1351. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00132.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Metten P, Cameron AJ, Wahlsten D. An analysis of the genetics of alcohol intoxication in inbred mice. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;28:785–802. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Harris RA, Arends MA, Koob GF. Alcohol-related genes: contributions from studies with genetically engineered mice. Addict Biol. 2006;11:195–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawshaw LI, Wallace HL, Christensen R, Crabbe JC. Influence of ethanol on thermoregulation: mapping quantitative trait loci. Physiol Genomics. 2001;7(2):159–169. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00041.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daws LC, Montanez S, Munn JL, Owens AM, Baganz NL, Boyce-Rustay J, Millstein RA, Wiedholz L, Murphy DL, Holmes A. Ethanol inhibits clearance of brain serotonin by a serotonin transporter-independent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6431–6438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4050-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing C, Rodd-Henricks KK, Flaherty L, Dudek BC. Genetic analysis of the psychomotor stimulant effect of ethanol. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:140–151. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183X.2003.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews E, Racz I, Lacava AD, Barth A, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Wienker TF, Zimmer A. Quantitative trait loci contributing to physiological and behavioural ethanol responses after acute and chronic treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:155–169. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenberg HJ, Strother WN, McClintick JN, Tian H, Stephens M, Jerome RE, Lumeng L, Li TK, McBride WJ. Gene expression in the hippocampus of inbred alcohol-preferring and -nonpreferring rats. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4:20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Walter NA, Dick DM, Buck KJ, Crabbe JC. A comparison of selected quantitative trait loci associated with alcohol use phenotypes in humans and mouse models. Addict Biol. 2010;15:185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin VG, Markel PD, Johnson TE, Gehle VM, Jones BC. Common quantitative trait loci for alcohol-related behaviors and central nervous system neurotensin measures: hypnotic and hypothermic effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:911–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr C, Shirley RL, Crabbe JC, Belknap JK, Buck KJ, Phillips TJ. The syntaxin binding protein 1 gene (Stxbp1) is a candidate for an ethanol preference drinking locus on mouse chromosome 2. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:708–720. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000164366.18376.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez JR, Vogler GP, Tarantino LM, Vignetti S, Plomin R, McClearn GE. Sex-exclusive quantitative trait loci influences in alcohol-related phenotypes. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:647–652. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19991215)88:6<647::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehle VM, Erwin VG. Common quantitative trait loci for alcohol-related behaviors and CNS neurotensin measures: voluntary ethanol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:401–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill K, Boyle AE. Genetic analysis of alcohol intake in recombinant inbred and congenic strains derived from A/J and C57BL/6J progenitors. Mamm Genome. 2005;16:319–331. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey HM, Kaiser AL, Johnson TE, Bennett B, Sikela JM, Zahniser NR. Norepinephrine transporter: a candidate gene for initial ethanol sensitivity in inbred long-sleep and short-sleep mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1759–1768. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183009.57805.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefner K, Holmes A. An investigation of the behavioral actions of ethanol across adolescence in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:311–322. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0646-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitzemann R, Cipp L, Demarest K, Mahjubi E, McCaughran J., Jr Genetics of ethanol-induced locomotor activation: detection of QTLs in a C57BL/6J × DBA/2J F2 intercross. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:956–962. doi: 10.1007/s003359900906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Saba L, Kechris K, Bhave SV, Hoffman PL, Tabakoff B. Genomic insights into acute alcohol tolerance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:792–800. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakihana R, Brown DR, McClearn GE, Tabershaw IR. Brain sensitivity to alcohol in inbred mouse strains. Science. 1966;154:1574–1575. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3756.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Mason G, Trevisan L, D’Souza DC. N-methyl-d-aspartate glutamate receptors and alcoholism: reward, dependence, treatment, and vulnerability. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;99:79–94. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(03)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmanger B, Lawler M, Coulombe S, Murray R, Cooper S, Polyakov Y, Belknap J, Hitzemann R. Further studies on using multiple-cross mapping (MCM) to map quantitative trait loci. Mamm Genome. 2006;17:1193–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manichaikul A, Moon JY, Sen S, Yandell BS, Broman KW. A model selection approach for the identification of quantitative trait loci in experimental crosses, allowing epistasis. Genetics. 2009;181:1077–1086. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.094565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClearn G, Rodgers DA. Differences in alcohol preference among inbred strains of mice. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1959;20:691–695. [Google Scholar]

- McClearn GE, Tarantino LM, Rodriguez LA, Jones BC, Blizard DA, Plomin R. Genotypic selection provides experimental confirmation for an alcohol consumption quantitative trait locus in mouse. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2:486–489. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo JA, Shendure J, Pociask K, Silver LM. Identification of sex-specific quantitative trait loci controlling alcohol preference in C57BL/6 mice. Nat Genet. 1996;13:147–153. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metten P, Best KL, Cameron AJ, Saultz AB, Zuraw JM, Yu CH, Wahlsten D, Crabbe JC. Observer-rated ataxia: rating scales for assessment of genetic differences in ethanol-induced intoxication in mice. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:360–368. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00086.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner LC, Buck KJ. Identifying quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and genes (QTGs) for alcohol-related phenotypes in mice. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2010;91:173–204. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozhui K, Ciobanu DC, Schikorski T, Wang X, Lu L, Williams RW. Dissection of a QTL hotspot on mouse distal chromosome 1 that modulates neurobehavioral phenotypes and gene expression. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan MK, Ponomarev I, Hitzemann RJ, Belknap JK, Tabakoff B, Harris RA, Crabbe JC, Blednov YA, Grahame NJ, Phillips TJ, Finn DA, Hoffman PL, Iyer VR, Koob GF, Bergeson SE. Toward understanding the genetics of alcohol drinking through transcriptome meta-analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6368–6373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510188103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newlin DB, Thomson JB. Alcohol challenge with sons of alcoholics: a critical review and analysis. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:383–402. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palachick B, Chen YC, Enoch AJ, Karlsson RM, Mishina M, Holmes A. Role of major NMDA or AMPA receptor subunits in MK-801 potentiation of ethanol intoxication. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1479–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce JL, Derr R, Shendure J, Kolata T, Silver LM. A major influence of sex-specific loci on alcohol preference in C57Bl/6 and DBA/2 inbred mice. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:942–948. doi: 10.1007/s003359900904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Crabbe JC, Metten P, Belknap JK. Localization of genes affecting alcohol drinking in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:931–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Belknap JK, Buck KJ, Cunningham CL. Genes on mouse chromosomes 2 and 9 determine variation in ethanol consumption. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:936–941. doi: 10.1007/s003359900903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, McClearn GE. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) analyses and alcohol-related behaviors. Behav Genet. 1993;23:197–211. doi: 10.1007/BF01067425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarev I, Crabbe JC. Characterization of acute functional tolerance to the hypnotic effects of ethanol in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:991–997. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000131978.79857.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe RA, Bludeau P, Asperi W, Fay T, Deng XS, Erwin VG, Deitrich RA. Confirmation of quantitative trait loci for ethanol sensitivity and neurotensin receptor density in crosses derived from the inbred high and low alcohol sensitive selectively bred rat lines. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:343–354. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe RA, Erwin VG, Bludeau P, Deng X, Fay T, Floyd KL, Deitrich RA. A major QTL for acute ethanol sensitivity in the alcohol tolerant and non-tolerant selected rat lines. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:611–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger FO, Cunningham CL. Ethanol induced conditioned taste aversion in BXD recombinant inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1234–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Kimpel MW, Edenberg HJ, Bell RL, Strother WN, McClintick JN, Carr LG, Liang T, McBride WJ. Differential gene expression in the nucleus accumbens with ethanol self-administration in inbred alcohol-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:481–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustay NR, Crabbe JC. Genetic analysis of rapid tolerance to ethanol’s incoordinating effects in mice: inbred strains and artificial selection. Behav Genet. 2004;34:441–451. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000023649.60539.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustay NR, Wahlsten D, Crabbe JC. Assessment of genetic susceptibility to ethanol intoxication in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2917–2922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437273100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Low level of response to alcohol as a predictor of future alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:184–189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp BM, Chen H, Gong S, Wu X, Liu Z, Hiler K, Taylor WL, Matta SG. Gene expression in accumbens GABA neurons from inbred rats with different drug-taking behavior. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:778–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00716.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley RL, Walter NA, Reilly MT, Fehr C, Buck KJ. Mpdz is a quantitative trait gene for drug withdrawal seizures. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:699–700. doi: 10.1038/nn1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabakoff B, Saba L, Kechris K, Hu W, Bhave SV, Finn DA, Grahame NJ, Hoffman PL. The genomic determinants of alcohol preference in mice. Mamm Genome. 2008;19:352–365. doi: 10.1007/s00335-008-9115-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino LM, McClearn GE, Rodriguez LA, Plomin R. Confirmation of quantitative trait loci for alcohol preference in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1099–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadasz C, Saito M, Gyetvai BM, Oros M, Szakall I, Kovacs KM, Prasad VV, Morahan G, Toth R. Mapping of QTLs for oral alcohol self-administration in B6.C and B6.I quasi-congenic RQI strains. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1099–1112. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle N, Hauschild M, Lubec G, Holmes A, Singewald N. Rescue of impaired fear extinction and normalization of cortico-amygdala circuit dysfunction in a genetic mouse model by dietary zinc restriction. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13586–13596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0849-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Oswald L, Wand G. The cyclic AMP/protein kinase A signal transduction pathway modulates tolerance to sedative and hypothermic effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1220–1225. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000081626.02910.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1 Average rotarod training latency. A S1 and F2 had a lower latency to fall than B6. B Frequency histogram illustrates normal distribution (dashed line is normal distribution) of training index scores in the F2 population. C A scan for single-locus main effects found several suggestive and significant loci (black) and a scan for sex-interacting loci found a locus on Chr 5. An additional locus on distal 7 may also interact with sex. D Effect plots for each of the main effects and a sex-interacting locus; *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM (EPS 1228 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2 Rotarod training index. A S1 had a higher training index (increase in latency to fall from training trial 1 to trial 10) than F2 or F1. B Frequency histogram illustrates normal distribution (dashed line is normal distribution) of training index scores in the F2 population. C A scan for single-locus main effects found a suggestive locus on Chr 11. D Effect plot for the peak locus on Chr 11; *p < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM (EPS 1111 kb)