Abstract

The emergency room (ER) represents the main system entry for crises-based health care visits. It is estimated that 2% to 10% of children visiting the ER are victims of child abuse and neglect (CAN). Therefore, ER personnel may be the first hospital contact and opportunity for CAN victims to be recognised. Early diagnosis of CAN is important, as without early identification and intervention, about one in three children will suffer subsequent abuse. This educational paper provides the reader with an up-to-date and in-depth overview of the current screening methods for CAN at the ER. Conclusion: We believe that a combined approach, using a checklist with risk factors for CAN, a structured clinical assessment and inspection of the undressed patient (called ‘top–toe’ inspection) and a system of standard referral of all children from parents who attend the ER because of alcohol or drugs intoxication, severe psychiatric disorders or with injuries due to intimate partner violence, is the most promising procedure for the early diagnosis of CAN in the ER setting.

Keywords: Child abuse and neglect, Emergency room, Risk factors, Partner violence, Checklist, Screening methods

Introduction

Child abuse and neglect (CAN) is a highly prevalent important medical and social problem [13, 19, 28, 50, 58]. Studies based on reporting by professionals or on administrative data performed in the US, Canada and the Netherlands show a national incidence rate of 1.6–3% [13, 18, 91–95, 97]. Community-based studies using self-reports of parents or children show tenfold or even higher rates than studies based on reporting by professionals or on administrative data, even though many incidences are never omitted or reported by parents or children [19, 28, 58].

Assessing the incidence of CAN in Europe is difficult as many different definitions are used and, in many countries, national registries are lacking. In a systematic review on physical abuse, Woodman et al. state in their review on screening methods for CAN in injured children presenting at the ER that the most effective protocol is to report all injured infants and children who have had previous contact with social services or mental health services or were registered in the Child Protection Register (CPR), so-called social work active children, to social services for further investigation [102].

Woodman et al. concluded that there is consistent evidence that physical abuse affects about 1 in 11 children in the UK each year [102]. However, the true extent of CAN remains unknown and many published studies have been criticised for under-representation [49, 51, 56, 64, 91–93, 95].

The emergency room (ER) represents the main system entry for crises-based health care visits. Therefore, ER personnel may be the first hospital contact and opportunity for CAN victims to be recognised. It is estimated that 2% to 10% of children visiting the ER are victims of CAN [4, 5, 32, 35, 38, 42, 70, 72]. Other studies, one from New York and two from the Netherlands, show significantly lower figures (respectively, 0.14% and 0.1% of confirmed cases and 0.2% of suspected CAN) [6, 43, 54]. Reasons for the low incidence in these three studies are not clear. One possible explanation is a low number of completed CAN checklists [54]. Knowledge, training, attitude and experience of health care personnel, socioeconomic status of the family, familiarity, injury characteristics and concerns about lost patients revenue and available resources for referral are factors that have shown to play a role in identification and reporting of CAN [20–22, 25, 41, 75, 89].

Recognising CAN victims in the everyday routine of an ER is a major challenge for ER health care personnel. There is evidence that potential CAN is under-detected by clinical as well as nursing staff [27, 40, 67, 68, 71, 74, 81, 84]. Early diagnosis is very important because, without early identification and intervention, approximately one in three children will suffer subsequent CAN [12, 76, 82]. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that 20–30% of children and youth who die from CAN have previously been seen by health care providers for abusive sequelae before CAN was formally identified [8, 40, 45].

Another important reason for early detection is the possible prevention of serious long-term adverse physical and psychological health outcomes as well as behaviours that increase the risks for such outcomes and criminality. Important retrospective and ongoing prospective studies with adults show graded relationship between the number of categories of childhood exposure (the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) score) and adult health risk behaviours and diseases [1, 2, 14, 15]. The number of categories of ACE showed a graded relationship to the presence of adult diseases including ischaemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures and liver disease, the leading causes of death in adults. The effect of ACE seems not to be influenced by social changes over time [16]. Studies on behaviour have shown that victims of CAN are at risk for young adult tobacco smoking, preteen alcohol use and unsafe sexual behaviour [31, 36, 77, 78, 90]. Other studies have shown a relation between CAN and an increased risk for hospital-based treatment prior to 18 years for physical and mental health symptoms, ranging from asthma to depressive disorders [9–11, 37, 39, 46, 62, 66, 87, 96]. On a more fundamental level, studies on neurobiological effects of CAN point to structural and functional abnormalities in brain development [59, 85, 86]. The effect of CAN has been observed in several neurobiological systems: atypical development of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; reduced hippocampus volume, a structure implicated in memory formation and retrieval (learning); structural and functional abnormalities have been observed in the prefrontal cortex, a region implicated in emotion regulation, planning and perspective taking, and in the amygdala, a structure involved in fear responses [2, 55].

In light of the above, it is clear that early recognition of CAN is paramount. However, health care professionals often fail to recognise victims of child maltreatment and, therefore, there is an urgent need for reliable screening methods for CAN in ERs [8, 52, 67, 68, 74, 84, 88, 99]. In this review, we will present an overview of published screening methods and present the methods that, in our view, are the most likely to enhance CAN detection at ERs.

Overview of screening methods for child abuse and neglect at ERs

The aim of a screening method at the ER should be to detect CAN with a high sensitivity and specificity. Missing CAN may have detrimental effects on the physical and mental health of the child, both in the short term as well as in the long term. In the most severe CAN cases, it can even result in the death of a child. On the other hand, a false-positive test in suspected CAN in nearly all cases will have a severe social impact. Such an outcome will put both parents/caretakers and the child under strain; it might lead to formal complaints and disciplinary cases. It can also lead to a lower compliance by ER personnel, thus decreasing the effect of the screening method.

For this educational paper, screening methods for the detection of CAN are divided into six categories.

Checklists with risk factors

Throughout the world, ERs use checklists with risk factors for CAN [5, 53, 54, 81, 101, 102]. In the Netherlands, many ERs use a checklist with nine risk factors (the so-called SPUTOVAMO list, Table 1), or a variant of this list, based on personal/local experience or literature on risk factors for child maltreatment. Sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of the SPUTOVAMO list are unknown. In a combined paper on three systematic reviews, Woodman et al. [101] presented risk factors such as age, repeated ER attendance and type of injury as markers for CAN in injured children attending ERs. Their study showed that, although all included studies were of poor scientific quality, age can be an important factor. Infancy increased the risk of physical abuse or neglect in severely injured or admitted children (likelihood ratios (LRs), 7.7–13.0; two studies) but was not strongly associated in all injured children attending the ER (LR, 1.5; 95% CI, 0.9, 2.8; one study). Repeat attendance did not substantially increase the risk of abuse or neglect and may be confounded by chronic disease and socioeconomic status (LRs, 0.8–3.9; three studies). However, to date, none of these widely used risk factors have a scientifically proven sensitivity, specificity and predictive value.

Table 1.

Dutch SPUTOVAMO checklist

| The 9 questions on the Dutch SPUTOVAMO checklist | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Which type of injury? (contusion, stab wound, burn, cut, etcetera) | |||

| Which place? (construct drawing) | Is this a normal place for this kind of injury? | ||

| □ yes | □ no* | ||

| What are the external characteristics of the injury? (color, form, border, etcetera) | Does the injury look usual? | ||

| □ yes | □ no* | ||

| When did the accident happen? How much time ago? | Does the appearance of the injury fit with the stated age? | ||

| □ yes | □ no* | ||

| What was the cause of the accident? What explanation is given? | Does the explanation fit with sort, place and appearance of the injury? | ||

| □ yes | □ no* | □ doubtful* | |

| Who caused the accident? | Is this person present in the ER? | ||

| □ yes | □ no* | □ not applicable | |

| Were witnesses present? Who? | Are the witnesses present in the ER? | ||

| □ yes | □ no* | □ not applicable | |

| What measures were taken by parents, carers or others? | Were the undertaken measures appropriate? | ||

| □ yes | □ no* | Why not? | |

| Which old injuries can be seen? | Did somebody perform an inspection for old injuries? | ||

| □ yes | □ no | ||

| Were old injuries found? | |||

| □ yes* | □ no | ||

| Do you have a suspicion of child abuse or neglect? | |||

| □ yes* | □ no | ||

This is a translation of the Dutch SPUTOVAMO checklist for child maltreatment at the ER. SPUTOVAMO is an acronym in which each letter represents one question on the form

*Direct referral for further assessment by specialised paediatrician

Another systematic review of Woodman et al. was performed to determine the clinical effectiveness of screening tests for physical abuse, amongst others checklists with risk factors, in children attending ERs in the UK [102]. A total of 66 studies (11 unpublished), carried out between 2004 and 2006, were included. Again, the overall quality of the studies was poor. The included studies only showed indirect evidence that checklists with risk factors may improve the sensitivity of the standard care clinical screening assessment. This evidence was derived from evaluating the changes in the referral rate for suspected abuse after the introduction of a checklist. All studies showed an increase in referrals, but whether this is due to true-positive or false-positive cases is unknown, as none of the studies reported confirmation or exclusion of CAN. The included studies did not analyse which component of a checklist was most predictive of abuse. The performance of the clinical screening assessment was poorly quantified and there was no evidence that any screening instrument was specifically sensitive for physical abuse.

A second systematic review on the value of screening tests in the ER was published by Louwers et al. [53]. Only four studies in which the intervention consisted of a checklist for indicators of risk for child abuse were included and assessed for quality. After implementation, there was a 180% increase in the rate of suspicion for CAN, but the number of confirmed cases of child abuse, reported in only two out of the four studies, showed no significant increase. A study from the same author performed in seven Dutch hospitals states a somewhat higher detection rate of suspected CAN in hospitals which have a higher completion rate of the checklist (checklist completed in 36% (16–56%) vs. in hospitals with a low completion of 0.4%) [54]. The rate of suspected CAN in these hospitals was 0.3% vs. 0.1%.

As mentioned before, a screening method yielding many false positives is highly unwanted because of the severe social consequences and the risk of downgrading the confidence in the screening method. This could lead to a decreased compliance of the ER personnel, leading to an even worse performance of the screening method.

Routine review of all ER records by a trained professional

The systematic review of Woodman et al. showed weak evidence that a community liaison nurse (CLN) improved the performance of the screening assessment in the ER by thorough review of all ER records of children [102]. Records of children with possible child protection concerns were presented by the CLN at a weekly child protection safety net meeting attended by the CLN, a consultant paediatrician, a hospital social worker and other staff. In this study, CLN review resulted in referral of nine additional children to social services (36% increase), compared to referral by clinical assessment alone. Using a clinical effectiveness model, Woodman et al. concluded that a combination of standard screening with dedicated CLN screening increased sensitivity from 43.5% to 59.0% and that the false-positive rate increased from 5% to 8.9%. However, given the poor quality of the data, these estimates are highly uncertain.

Referring all children known to have had previous contact with social services, mental health services or child protection services

Woodman et al. state in their review on screening methods for CAN in injured children presenting at the ER that the most effective protocol is to report all injured infants and children who have had previous contact with social services or mental health services or were registered in the CPR, so-called social work active children, to social services for further investigation [102]. Their statement is based on more than one assumption and several unpublished studies. Government guidelines in the UK specify that ER staff should be familiar with local procedures for checking children against the relevant CPR [3, 29, 73]. There is no uniformity of the way in which UK ERs access the CPR and there is also substantial variation in the criteria used to check the register. The most common form of access (via the duty social worker) often fails to meet the needs of ERs, principally because it is too time consuming [73]. One study reported that only 30% of 190 UK ERs routinely checked if children were registered in the CPR [73]. The risk of prejudices against parents based on CPR information is also mentioned, especially in presentations with inconsolable infant crying [24]. Sensitivity and specificity of assessing CPR status related to ER presentation is unknown, neither is the positive or negative predictive value. False negative results because the child has no CPR record while the injury is a result from non-accidental trauma are well recognised [65].

An increasing number of countries, including the UK and the Netherlands, are developing parallel data systems operating as a bridge between key professionals and agencies that offer assessments and services to children [13]. This should make it easier to determine whether a child had previous contact with social services or child protection services (CPS). To date, strict European laws on privacy protection prohibit large-scale implementation of these parallel data systems.

Various studies reporting on the prevalence of previous social work involvement among abused children have been published. Two Canadian studies address this subject. The first study, based on self-reported physical abuse in young adults, found that only 5% recalled any previous contact with social services, and only 9% of those reporting severe physical abuse [56]. The other study, based on children investigated for any type of CAN by social services, found that 42% had had previous investigations by social services [92]. Although these very different results may reflect recall bias in the first study, they raise the possibility that detection is focused on a particular subpopulation of abused children, while a large majority remains undetected. One Italian study, based on data from19 ERs that classified any type of suspected abuse based on a risk score, showed that children at high risk of abuse were four times more likely to have had previous contact with social services or mental health services than low-risk children [70]. From 1994 to 2000, in Northern Ireland, 191 children registered in the CPR were followed, 41% visited the ER on several occasions. Most ER visits were the result of accidental trauma. At the time of presentation, only six children (3%) were identified as being on the CPR [23].

Performing a complete physical inspection of every child presenting at the ER

Only one study on the performance of a checklist combined with a physical inspection of the undressed child has been published [72]. This study, conducted in 1976, dealt with children less than 6 years of age seen with an injury or poisoning in the Montreal Children’s Hospital ER. This ER, at the time of the study, dealt with 6,000 injured children under the age of 6 annually. The clinical assessment comprised full physical examination by specially trained nurses who examined undressed children for bruises, burns and cuts. They also completed a ten-point checklist and discussed their findings with the attending physician. Additional assessment was performed if necessary. Children with suspected abuse were referred to the hospital child protection team (test positive). To ascertain false negatives (abused children not referred), all ER records were reviewed by the investigators and every suspicious case was interviewed by a public health nurse at a special home or hospital visit and, if concerns persisted, referred to the child protection team. The reference standard was confirmation or exclusion of abuse by the child protection team or non-referral to the team. This combined approach of a checklist with a full physical inspection showed a promising sensitivity of 89%, with a false-positive rate of only 1% in this specific group of patients. We will illustrate this approach with a clinical case (Case A).

Referring all children from parents who attend the ER because of alcohol or drugs intoxication, severe psychiatric disorders or with injuries due to intimate partner violence

It is a well-known fact that parental alcohol and/or drug dependence, psychiatric illnesses and intimate partner (domestic) violence are risk factors for CAN [17, 26, 30, 33, 34, 38, 44, 47, 48, 57, 69, 79, 80, 91, 92, 95, 97, 98, 100, 103].

In the Hague, the Netherlands, a new policy has been introduced in which an attendance of a parent at the ER with injuries related to intimate partner violence, alcohol or drugs intoxication or with a severe psychiatric disorder is automatically followed by a mandatory report to the Advisory and Reporting Centre Child Abuse (Advies- en Meldpunt Kindermishandeling, AMK) of all children in this household. These mandatory reports are made irrespective of the fact whether or not the children were in the company of the parent at the time of presentation. The hospitals and child advocacy centres involved in this protocol claim that 98% of reported cases of possible CAN proved to be cases of CAN indeed. This figure is not surprising since being a witness of domestic violence is contained within the definition of CAN. In how many cases an intervention initiated by the AMK was necessary is not known.

A slightly different approach is used in Amsterdam; here, ERs of all hospitals refer children, from the same categories of parents attending the ER, within 1 week after initial presentation to a paediatrician specialised in social paediatrics [63]. The paediatrician carries out a full protocol for possible CAN and, if deemed necessary, refers the family for further help and intervention.

Scientific data for both approaches is currently lacking, but those involved ardently defend their approach as a potential efficient tool for the ER. We will illustrate this approach with a clinical case (Case B).

Identifying and referring all pregnant women presenting at the ER with specific well-defined psychosocial risk criteria related to drug addiction, mental insufficiency and particular social circumstances of possible relevance to problems of pregnancy and early child development

A pregnant woman’s psychological health is a significant predictor of postpartum family violence [7]. In a study performed in Sweden from 1983 to 1999, amongst 1,575 pregnant women, an index group of 78 women was identified with specific psychosocial risk criteria related to drug addiction, mental insufficiency and particular social circumstances of possible relevance to problems of pregnancy and early child development [83]. A further 78 pregnant women who did not meet the inclusion criteria were used as a reference group. During a follow-up period of 16 years, 43 (57%) of the original index children and 63 (82%) of the original reference children were examined on indices of mental health and the presence of CAN. The index children, especially the boys, displayed significantly poorer mental health. Index children had an increased odd ratio of 16–27 for different social welfare interventions, and CAN had been investigated in 27% of index children compared to 1% of reference children. Early home visitation and parent education programmes are examples of evidence-based prevention programmes which, when introduced early, can prevent CAN [60]. Prenatal referral allows for early intervention, treatment and, when necessary, introduction of a guardian already before birth and early out of home placement [61]. Routine screening for psychosocial concerns of all pregnant women presenting at the ER could be a promising tool for early recognition and prevention of CAN. We will illustrate this approach with a clinical case (Case C).

Conclusion

In this educational paper, six different strategies aimed at a timely detection of CAN at the ER have been presented. For all approaches, it can be concluded that, at this time, there is no superior screening method for the detection of CAN at the ER.

In spite of the lack of evidence, the authors of this educational paper have a strong preference towards a combination of both a complete physical inspection of every child (called ‘top–toe’ inspection) presenting at the ER, in which case the age range has to be explored, and a system of standard referral of all (born and unborn) children from parents who attend the ER because of alcohol or drugs intoxication, severe psychiatric disorders or with injuries due to intimate partner violence. Although this will significantly increase the workload of all physicians involved, it seems to be the most valid approach. Indeed, we did find more cases of CAN after the combined introduction of these two approaches.

Cases

Case A

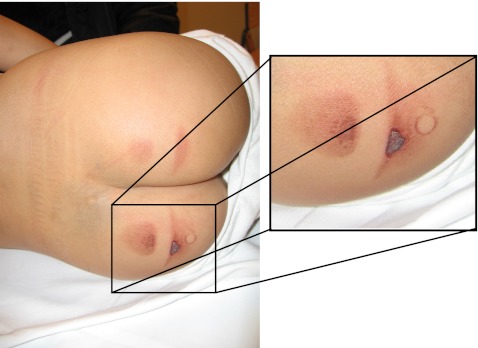

A 4-year-old boy presented at the ER 24 h after a staircase fall in his new home. The fall was not witnessed; he had direct complaints of shoulder pain and was sent to bed with an analgesic. As the pain lasted, his mother brought him to our ER. After initial inspection, he was send to radiology where an upper arm fracture was documented. This fracture is consistent with the clinical history and appropriate treatment could be given. However, the top–toe examination revealed bilateral skin burns of the buttocks with clear margins consistent with the imprint of an object, possibly an iron (Fig. 1). This finding led to an in-depth investigation, resulting in a diagnosis of child abuse. As a consequence of this diagnosis, child support measures could be taken and the security of the boy could be guaranteed.

Fig. 1.

Patient A showing Mongolian spots and bilateral sharply demarcated skin burns on the buttocks

Case B

Four days after an ER presentation of a female patient with injuries caused by domestic violence, her twins aged 3 years (brother and sister) were, in keeping with our protocol, presented at the outpatient paediatric clinic. At this time, a paediatrician performed a full clinical history and a physical exam. A physical exam was performed; during this top–toe examination, the girl asked the paediatrician to look at her ‘poeni’ (vagina). The paediatrician asked her why she thought special attention was necessary. The answer revealed a story of sexual abuse by her stepfather. This was independently confirmed by her twin brother. These findings were directly reported to the CPS, the mother filed charges and both the mother and the children were placed in a safe house.

Case C

A homeless patient was presented at the ER with psychiatric disorders and cocaine intoxication at 23 weeks pregnancy. Up to that time, obstetric controls were not performed, which is seen as a risk factor to the unborn child. The unborn child was reported to the CPS; this currently is a viable option in the Netherlands and has led to numerous successful interventions during pregnancies. Based on the investigation by the CPS, a guardian for the unborn child was appointed and the mother was placed in a rehabilitation clinic. She managed to stay clean and delivered a healthy baby at full term. With support from social services and youth services, she is now able to raise her child in her own home. The child is developing well, although CPS is still involved.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Mrs. T. Sieswerda and Mrs. S. Brilleslijper-Kater for their comments.

Funding

This study was funded by Stichting Kinderpostzegels Nederland, a children’s charity with the slogan ‘for children, by children’. The authors were completely independent from funders in writing this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- ER

Emergency room

- CAN

Child abuse and neglect

References

- 1.Anda RF, Butchart A, Felitti VJ, Brown DW. Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audit Commission . By accident or design: improving A&E services in England and Wales. London: Audit Commission; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benger JR, McCabe SE. Burns and scalds in pre-school children attending accident and emergency: accident or abuse? Emerg Med J. 2001;18:172–174. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.3.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benger JR, Pearce V. Simple intervention to improve detection of child abuse in emergency departments. BMJ. 2002;324:780. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7340.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleeker G, Vet NJ, Haumann TJ, van Wijk IJ, Gemke RJ. Increase in the number of reported cases of child abuse following adoption of a structured approach in the VU Medical Centre, Amsterdam, in the period 2001–2004. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005;149:1620–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll JC, Reid AJ, Biringer A, Midmer D, Glazier RH, Wilson L, Permaul JA, Pugh P, Chalmers B, Seddon F, Stewart DE. Effectiveness of the Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) form in detecting psychosocial concerns: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2005;173:253–259. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carty H, Pierce A. Non-accidental injury: a retrospective analysis of a large cohort. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2919–2925. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark C, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld SA. Does the influence of childhood adversity on psychopathology persist across the lifecourse? A 45-year prospective epidemiologic study. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark DB, De Bellis MD, Lynch KG, Cornelius JR, Martin CS. Physical and sexual abuse, depression and alcohol use disorders in adolescents: onsets and outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cutajar MC, Mullen PE, Ogloff JR, Thomas SD, Wells DL, Spataro J. Psychopathology in a large cohort of sexually abused children followed up to 43 years. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:813–822. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darok M, Reischle S. Burn injuries caused by a hair-dryer—an unusual case of child abuse. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;115:143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(00)00324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department for Children, Schools and Families (2008) DCSF: referrals, assessments off children and young people who are the subject of a child protection plan or are on child protection registers: year ending 31 March 2007

- 14.Dong M, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Giles WH, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and self-reported liver disease: new insights into the causal pathway. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1949–1956. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.16.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williams JE, Chapman DP, Anda RF. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: adverse childhood experiences study. Circulation. 2004;110:1761–1766. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH, Anda RF. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900. Prev Med. 2003;37:268–277. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubowitz H, Bennett S. Physical abuse and neglect of children. Lancet. 2007;369:1891–1899. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60856-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Euser EM, van Ijzendoorn MH, Prinzie P, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Prevalence of child maltreatment in The Netherlands. Child Maltreat. 2010;15:5–17. doi: 10.1177/1077559509345904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fallon B, Trocme N, Fluke J, MacLaurin B, Tonmyr L, Yuan YY. Methodological challenges in measuring child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flaherty EG, Sege R. Barriers to physician identification and reporting of child abuse. Pediatr Ann. 2005;34:349–356. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20050501-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaherty EG, Sege RD, Griffith J, Price LL, Wasserman R, Slora E, Dhepyasuwan N, Harris D, Norton D, Angelilli ML, Abney D, Binns HJ. From suspicion of physical child abuse to reporting: primary care clinician decision-making. Pediatrics. 2008;122:611–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flaherty EG, Sege R, Price LL, Christoffel KK, Norton DP, O’Connor KG. Pediatrician characteristics associated with child abuse identification and reporting: results from a national survey of pediatricians. Child Maltreat. 2006;11:361–369. doi: 10.1177/1077559506292287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flanagan NM, Macleod C, Jenkins MG, Wylie R. The Child Protection Register: a tool in the accident and emergency department? Emerg Med J. 2002;19:229–230. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.3.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fletcher AK, Burke DP. Presentation to accident and emergency with crying or screaming and likelihood of child protection registration. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:17–18. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser JA, Mathews B, Walsh K, Chen L, Dunne M. Factors influencing child abuse and neglect recognition and reporting by nurses: a multivariate analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freisthler B, Merritt DH, LaScala EA. Understanding the ecology of child maltreatment: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Child Maltreat. 2006;11:263–280. doi: 10.1177/1077559506289524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert R, Kemp A, Thoburn J, Sidebotham P, Radford L, Glaser D, MacMillan HL. Recognising and responding to child maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373:167–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HM Government (2010) Working Together to Safeguard Children: a guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. Department for Children, Schools and Families. Available at http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/everychildmatters/

- 30.Grietens H, Geeraert L, Hellinckx W. A scale for home visiting nurses to identify risks of physical abuse and neglect among mothers with newborn infants. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamburger ME, Leeb RT, Swahn MH. Childhood maltreatment and early alcohol use among high-risk adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:291–295. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hampton RL, Newberger EH. Child abuse incidence and reporting by hospitals: significance of severity, class, and race. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:56–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hindley N, Ramchandani PG, Jones DP. Risk factors for recurrence of maltreatment: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:744–752. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.085639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holt S, Buckley H, Whelan S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: a review of the literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holter JC, Friedman SB. Child abuse: early case finding in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 1968;42:128–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houck CD, Nugent NR, Lescano CM, Peters A, Brown LK. Sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior: beyond the impact of psychiatric problems. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:473–483. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hovens JG, Wiersma JE, Giltay EJ, van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Zitman FG. Childhood life events and childhood trauma in adult patients with depressive, anxiety and comorbid disorders vs. controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118:933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irish L, Kobayashi I, Delahanty DL. Long-term physical health consequences of childhood sexual abuse: a meta-analytic review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:450–461. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, Reinert SE, Hay TC. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1999;281:621–626. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones R, Flaherty EG, Binns HJ, Price LL, Slora E, Abney D, Harris DL, Christoffel KK, Sege RD. Clinicians’ description of factors influencing their reporting of suspected child abuse: report of the Child Abuse Reporting Experience Study Research Group. Pediatrics. 2008;122:259–266. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Droegenmueller W, Silver HK. The battered-child syndrome. JAMA. 1962;181(17–24):17–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keshavarz R, Kawashima R, Low C. Child abuse and neglect presentations to a pediatric emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2002;23:341–345. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kindler H. Screening for risk of child abuse and neglect. A practicable method? Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53:1073–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00103-010-1132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.King WK, Kiesel EL, Simon HK. Child abuse fatalities: are we missing opportunities for intervention? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:211–214. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000208180.94166.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lanier P, Jonson-Reid M, Stahlschmidt MJ, Drake B, Constantino J. Child maltreatment and pediatric health outcomes: a longitudinal study of low-income children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:511–522. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee LC, Kotch JB, Cox CE. Child maltreatment in families experiencing domestic violence. Violence Vict. 2004;19:573–591. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.573.63682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leventhal JM, Forsyth BW, Qi K, Johnson L, Schroeder D, Votto N. Maltreatment of children born to women who used cocaine during pregnancy: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 1997;100:E7. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.2.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levi BH, Brown G, Erb C. Reasonable suspicion: a pilot study of pediatric residents. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levin AV. Ophthalmic presentations. In: Meadow R, editor. ABC of child abuse. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1997. pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindberg DM, Lindsell CJ, Shapiro RA. Variability in expert assessments of child physical abuse likelihood. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e945–e953. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loiselle JM, Westle RE. Inpatient reports of suspected child abuse or neglect (SCAN): a question of missed opportunities in the acute care setting. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15:90–94. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199904000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Louwers EC, Affourtit MJ, Moll HA, De Koning HJ, Korfage IJ. Screening for child abuse at emergency departments: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:214–218. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.151654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Louwers EC, Korfage IJ, Affourtit MJ, Scheewe DJ, van de Merwe MH, Vooijs-Moulaert FA, Woltering CM, Jongejan MH, Ruige M, Moll HA, De Koning HJ. Detection of child abuse in emergency departments: a multi-centre study. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:422–425. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.202358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacMillan HL, Jamieson E, Walsh CA. Reported contact with child protection services among those reporting child physical and sexual abuse: results from a community survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1397–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mattejat F, Remschmidt H. The children of mentally ill parents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105:413–418. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.May-Chahal C, Cawson P. Measuring child maltreatment in the United Kingdom: a study of the prevalence of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:969–984. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCrory E, Viding E. The neurobiology of maltreatment and adolescent violence. Lancet. 2010;375:1856–1857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60842-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mikton C, Butchart A. Child maltreatment prevention: a systematic review of reviews. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:353–361. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.057075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Milligan K, Niccols A, Sword W, Thabane L, Henderson J, Smith A, Liu J. Maternal substance use and integrated treatment programs for women with substance abuse issues and their children: a meta-analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murali R, Chen E. Exposure to violence and cardiovascular and neuroendocrine measures in adolescents. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:155–163. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nederlands Jeugd Instituut (2010) Nederlands Jeugd Insituut. Available at http://www.nji.nl/eCache/DEF/1/21/544.html

- 64.Newton AS, Zou B, Hamm MP, Curran J, Gupta S, Dumonceaux C, Lewis M. Improving child protection in the emergency department: a systematic review of professional interventions for health care providers. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17:117–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nicol MF, Harris A. Child protection register—time for change. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:77–78. doi: 10.1136/emj.16.1.77-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e61–e67. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oral R, Blum KL, Johnson C. Fractures in young children: are physicians in the emergency department and orthopedic clinics adequately screening for possible abuse? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:148–153. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000081234.20228.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oral R, Yagmur F, Nashelsky M, Turkmen M, Kirby P. Fatal abusive head trauma cases: consequence of medical staff missing milder forms of physical abuse. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:816–821. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818e9f5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Osofsky JD. Prevalence of children’s exposure to domestic violence and child maltreatment: implications for prevention and intervention. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6:161–170. doi: 10.1023/a:1024958332093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palazzi S, de Girolamo G, Liverani T. Observational study of suspected maltreatment in Italian paediatric emergency departments. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:406–410. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.040790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pandya NK, Baldwin K, Wolfgruber H, Christian CW, Drummond DS, Hosalkar HS. Child abuse and orthopaedic injury patterns: analysis at a level I pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:618–625. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181b2b3ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pless IB, Sibald AD, Smith MA, Russell MD. A reappraisal of the frequency of child abuse seen in pediatric emergency rooms. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(87)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quin G, Evans R. Accident and emergency department access to the child protection register: a questionnaire survey. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:136–137. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ravichandiran N, Schuh S, Bejuk M, Al-Harthy N, Shouldice M, Au H, Boutis K. Delayed identification of pediatric abuse-related fractures. Pediatrics. 2010;125:60–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reijneveld SA, de Gea M, Wiefferink CH, Crone MR. Detection of child abuse by Dutch preventive child-healthcare doctors and nurses: has it changed? Child Abuse Negl. 2008;32:831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Seifert D, Krohn J, Larson M, Lambe A, Puschel K, Kurth H. Violence against children: further evidence suggesting a relationship between burns, scalds, and the additional injuries. Int J Legal Med. 2010;124:49–54. doi: 10.1007/s00414-009-0347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shin SH, Edwards EM, Heeren T. Child abuse and neglect: relations to adolescent binge drinking in the national longitudinal study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) Study. Addict Behav. 2009;34:277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shin SH, Edwards E, Heeren T, Amodeo M. Relationship between multiple forms of maltreatment by a parent or guardian and adolescent alcohol use. Am J Addict. 2009;18:226–234. doi: 10.1080/10550490902786959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sidebotham P, Heron J. Child maltreatment in the “children of the nineties”: a cohort study of risk factors. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:497–522. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sidebotham P, Heron J, Golding J. Child maltreatment in the “Children of the Nineties:” deprivation, class, and social networks in a UK sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:1243–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sidebotham PD, Pearce AV. Audit of child protection procedures in accident and emergency department to identify children at risk of abuse. BMJ. 1997;315:855–856. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7112.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Skellern CY, Wood DO, Murphy A, Crawford M. Non-accidental fractures in infants: risk of further abuse. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:590–592. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2000.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Svedin CG, Wadsby M, Sydsjo G. Mental health, behaviour problems and incidence of child abuse at the age of 16 years. A prospective longitudinal study of children born at psychosocial risk. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;14:386–396. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0487-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taitz J, Moran K, O’Meara M. Long bone fractures in children under 3 years of age: is abuse being missed in Emergency Department presentations? J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40:170–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Teicher MH. Commentary: childhood abuse: new insights into its association with posttraumatic stress, suicidal ideation, and aggression. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:578–580. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Teicher MH, Tomoda A, Andersen SL. Neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment: are results from human and animal studies comparable? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:313–323. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomas C, Hypponen E, Power C. Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: the role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1240–e1249. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tingberg B, Falk AC, Flodmark O, Ygge BM. Evaluation of documentation in potential abusive head injury of infants in a Paediatric Emergency Department. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:777–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tirosh E, Offer SS, Cohen A, Jaffe M. Attitudes towards corporal punishment and reporting of abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:929–937. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Topitzes J, Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and adult cigarette smoking: a long-term developmental model. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:484–498. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Trocme N, MacMillan H, Fallon B, De MR. Nature and severity of physical harm caused by child abuse and neglect: results from the Canadian Incidence Study. CMAJ. 2003;169:911–915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trocme NM, Tourigny M, MacLaurin B, Fallon B. Major findings from the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1427–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (2010) Statistics & research. Available at http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/

- 94.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families (2010) Child maltreatment 2007. Available at http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm07/cm07.pdf

- 95.U.S. Department of Health and Social Services, Administration for Children & Families (2010) Abuse, neglect, adoption & foster care research. National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4), 2004–2009. Available at http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/abuse_neglect/natl_incid/index.html

- 96.Vamosi M, Heitmann BL, Kyvik KO. The relation between an adverse psychological and social environment in childhood and the development of adult obesity: a systematic literature review. Obes Rev. 2010;11:177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.van IJzendoorn MH, Prinzie P, Euser EM, Groeneveld MG, Brilleslijper-Kater SN, van Noort-van der Linden AMT, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F, Mesman J, Klein Verlderman M, San Martin Beuk M, Ohlsen-Koole PC (2007) Kindermishandeling in Nederland Anno 2005: De Nationale Prevalentiestudie Mishandeling van Kinderen en Jeugdigen (NPM-2005)

- 98.Walsh C, MacMillan HL, Jamieson E. The relationship between parental substance abuse and child maltreatment: findings from the Ontario Health Supplement. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:1409–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weber MA, Risdon RA, Offiah AC, Malone M, Sebire NJ. Rib fractures identified at post-mortem examination in sudden unexpected deaths in infancy (SUDI) Forensic Sci Int. 2009;189:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wells K. Substance abuse and child maltreatment. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:345–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Woodman J, Lecky F, Hodes D, Pitt M, Taylor B, Gilbert R. Screening injured children for physical abuse or neglect in emergency departments: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:153–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Woodman J, Pitt M, Wentz R, Taylor B, Hodes D, Gilbert RE (2008) Performance of screening tests for child physical abuse in accident and emergency departments. Health Technol Assess 12(33):iii, xi–xiii, 1–95 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Wu SS, Ma CX, Carter RL, Ariet M, Feaver EA, Resnick MB, Roth J. Risk factors for infant maltreatment: a population-based study. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:1253–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]