Abstract

A detailed understanding of the mechanisms that underlie antibiotic killing is important for the derivation of new classes of antibiotics and clinically useful adjuvants for current antimicrobial therapies. Our efforts to understand why DinB (DNA Polymerase IV) overproduction is cytotoxic to Escherichia coli led to the unexpected insight that oxidation of guanine to 8-oxo-guanine in the nucleotide pool underlies much of the cell death caused by both DinB overproduction and bactericidal antibiotics. We propose a model in which the cytotoxicity of beta-lactams and quinolones predominantly results from lethal double-stranded DNA breaks caused by incomplete repair of closely spaced 8-oxo-deoxyguanine lesions, while the cytotoxicity of aminoglycosides might additionally result from mistranslation due to the incorporation of 8-oxo-guanine into newly synthesized RNAs.

Elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals (OH•), within prokaryotic cells potentiate cell death. For example, three different classes of bactericidal antibiotics (β-lactams, quinolones, and aminoglycosides), regardless of macromolecular target, ultimately result in cell death in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria via a common mechanism that produces OH• (1). Since elevated intracellular levels of OH• can damage DNA, lipids, and proteins, generalized oxidation catastrophe could result in cell death; however, our current work suggests that cell death is predominately elicited by specific oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool and its subsequent use in nucleic acid transactions.

DinB Overproduction Lethality Due to 8-oxo-dG Incorporation

The ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor hydroxyurea, although best known for stalling DNA replication forks and eliciting double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs), also causes bacterial cell death through the production of OH• (2). This stimulated us to test whether the cytotoxicity associated with overproduction of the E. coli translesion DNA polymerase DinB (DNA Pol IV) might result from an OH•-dependent process, because, like hydroxyurea, it slows the speed of replication forks and results in bacterial cell death presumably because of DSBs (3, 4). To test if OH• radicals underlie cell death resulting from DinB overproduction, we measured cell survival in the presence of thiourea (OH• scavenger) and 2,2′-dipyridyl (an iron chelator which prevents the Fenton reaction required for OH• production) (5–8). Thiourea and 2,2′-dipyridyl, which do not strongly effect cell growth (1), completely prevent cell death caused by DinB overproduction (Fig. 1A). In addition, DinB overproduction is not toxic in an anaerobic environment (Fig. 1B), consistent with OH• mediating DinB-induced cell death. However, in contrast to hydroxyurea, which significantly increases intracellular OH• levels (ca. 10 fold) (2), DinB overproduction has a more modest effect (ca. 1.6 fold) (Fig. 1D). Thus it seemed most likely that the elevated levels of DinB were lethal because of the increased use of oxidized deoxynucleotides, rather than because of the induction of high levels of OH•.

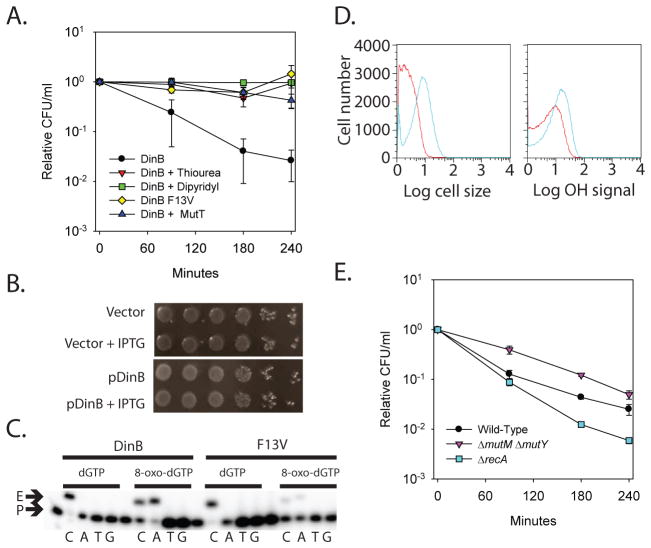

Fig. 1.

Evidence indicating that overproduction of DinB results in DSBs due to closely spaced 8-oxo-dG lesions. A. Lethality of DinB overproduction (black), measured by colony forming units (CFU) per milliliter (ml) relative to time zero, is reduced by thiourea (red), 2,2′-dipyridyl (green), and co-overproduction of MutT (blue). Overproduction of DinB F13V (yellow), which is incapable of incorporating 8-oxo-dG, is not lethal. B. Under anaerobic conditions, DinB overproduction is not cytotoxic; cell viability was assayed by ten-fold serial dilutions of cells overproducing DinB (pDinB + IPTG) and compared to non-induced (pDinB) and vector controls (Vector and Vector + IPTG). C. DinB and DinB F13V (F13V) primer extension analysis using dGTP and 8-oxo-dGTP as the incoming nucleotide and the four different templating bases. The starting primer (P) and extended product (E) are indicated. Lanes 1, 6, 11, and, 16 are unextended primer controls. D. Overproduction of DinB for 3 hours (blue) results in cell filamentation, but does not result in a substantial increase in intracellular OH• levels when compared to an uninduced control (red). The forward-scatter histogram (Cell Size arbitrary units; left) of a DinB overproducing strain suggests cell elongatation. Conversely, a modest increase in the HPF fluorescence signal (1.6 fold) compared to the control is observed in a DinB overproducing strain suggesting that intracellular OH• levels do not substantially increase (OH Signal arbitrary units; right). E. The lethality of DinB overproduction (black) is minimized in a ΔmutM ΔmutY background (purple), but enhanced in a ΔrecA background (blue).

The nucleotide pool is a significant target of ROS and guanine is particularly susceptible to oxidation due to its low redox potential (9, 10). One of the most intensively studied major products of guanine oxidation is 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxo-guanine) (10). 8-oxo-dG is potentially mutagenic because of its ability to base-pair with both cytosine and adenine (Fig. S1). DinB, like its human ortholog DNA Pol κ (11), is a translesion DNA polymerase that can utilize 8-oxo-dGTP as the incoming nucleotide, pairing it with either dC or dA, with a preference for dA (Fig. 1C). Mutation of DinB’s steric gate (F13V) severely reduces its ability to utilize 8-oxo-dGTP as an incoming nucleotide (Fig. 1C), as does mutation of the corresponding steric gate of Pol κ (Y112A) (11). Therefore, to test the hypothesis that DinB overproduction causes cell death by incorporating more 8-oxo-dG than the cell can tolerate, we overproduced DinB F13V, and as predicted, observed that this variant is not cytotoxic (Fig. 1A).

Although the observation that DinB F13V is not cytotoxic is consistent with our hypothesis that DinB overproduction is incorporating more 8-oxo-dG than the cell can handle, it does not exclude the possibility that the ability of DinB to copy over N2-dG adducts (12) is contributing to cell death. Therefore, we co-overproduced MutT, a nucleotide sanitizer of the GO system that, together with MutM and MutY, minimizes the deleterious effects of oxidized guanine (13). MutT, which hydrolyzes 8-oxo-dGTP to 8-oxo-dGMP (13), eliminates the cytotoxicity of DinB when co-overproduced (Fig. 1A). DinB overproduction in a ΔmutT strain is as cytotoxic as wild-type (Fig. S2), suggesting that DinB levels are rate limiting for death despite the fact that levels of 8-oxo-dGTP are extremely low even in a ΔmutT mutant (14), a conclusion which is consistent, with trace amounts of 8-oxo-dGTP usage during replication potentially having significant biological consequences (15).

Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that DinB is incorporating more 8-oxo-dG than the cell can tolerate, but two potential mechanisms of intolerance are possible: the accumulation of lethal mutations or the formation of lethal DSBs. It is unlikely that ca. 50% of the cells have obtained a lethal mutation within 90 minutes (Fig. 1A), as DinB moves as slow as 1 bp/second and thus has only copied ca. 5400 bp/replication fork (4). Instead, it seems more likely that cells are dying from DSBs as previously suggested (3), a possibility consistent with our observation that DinB overproduction results in the up-regulation of the SOS response as measured by microarray analysis (Table S1 and S2) and cell filamentation as measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 1D; 4.76 fold increase).

Although the absolute levels of 8-oxo-dG present in DNA in an unstressed ΔmutT strain are too low to cause chromosomal fragmentation (16), a change in the levels of 8-oxo-dGTP and/or a change in the ratios of the particular DNA polymerases operating in a cell (i.e., DinB overproduction in this case) could result in closely spaced 8-oxo-dG nucleotides. Closely spaced DNA lesions are potentially problematic since the proximity of individual DNA lesions can alter the ability of damage to be repaired (17) and subsequently result in DSBs (18). A single DSB in an E. coli cell has been known for decades to be potentially lethal (19). Thus, in principle, incomplete base excision repair by MutM and MutY glycosylases acting at closely spaced dC:8-oxo-dG and dA:8-oxo-dG pairs, respectively, could result in the generation of a lethal DSB (Fig. S3). A DNA polymerase prone to utilizing 8-oxo-dGTP as a substrate, such as DinB, would increase the likelihood of two 8-oxo-dG lesions being incorporated in close proximity, and thus the potential for a DSB. Direct incorporation of an 8-oxo-dG by a DNA polymerase close to an existing 8-oxo-dG could also lead to a lethal DSB event via the action of GO system glycosylases (Fig. S3). DSB formation by either of these mechanisms could be suppressed by MutT overproduction. In principle, the occurrence of a closely spaced dC:8-oxo-dG and 8-oxo-dG:C pair as a consequence of direct oxidation of DNA could also result in DSBs (Fig. S3), but these would not be suppressible by overproduction of MutT.

The processivity of DinB interacting with the β-clamp is 300–400 nucleotides (20) and thus, in principle, it could continue to replicate long enough to introduce multiple 8-oxo-dGs into DNA, setting up the potential for a MutM/MutY-mediated DSB. Consistent with this model, a ΔmutM ΔmutY mutant is less sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of DinB overproduction (Fig. 1E). The protective effect of ΔmutM ΔmutY may be less than that of MutT overproduction because other base excision repair enzymes that recognize 8-oxo-dG may additionally contribute to DSB formation (13). In addition, it is possible that MutT is also able to sanitize another oxidized dNTP, as can the human MutT homolog (21), and that its incorporation into DNA contributes to DSB formation through a MutM/MutY-independent process. Since cells repair DSBs by homologous recombination, the increased sensitivity of a ΔrecA strain to DinB overproduction (Fig. 1E) is consistent with this model of 8-oxo-dG-mediated DSB formation. Collectively, the above data suggest that incorporation of 8-oxo-dG into DNA during replication is cytotoxic due to DSBs generated by the incomplete action of base-excision repair systems designed to protect cells from the mutagenic effects of oxidized nucleotides, i.e., the cellular protector has become the executioner.

Bactericidal antibiotic lethality due, in part, to the oxidation of guanine nucleotides

We then wondered if the principle revealed by these experiments – an increase in closely spaced 8-oxo-dG lesions leading to DSBs – might also underlie cell death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Antibiotics can generally be classified as being bacteriostatic (preventing cell growth) or bactericidal (killing cells) (22). Bactericidal antibiotics had long been thought to kill via class-specific drug interactions, which usually fall into three categories: inhibitors of cell wall biosynthesis, DNA replication, and protein synthesis (23). However, it was recently shown that a common pathway that produces OH• contributes significantly to killing induced in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria by major classes of bactericidal antibiotics (1). Despite having different macromolecular targets, β-lactams (cell wall synthesis inhibitors), quinolones (DNA gyrase inhibitors), and aminoglycosides (protein synthesis inhibitors) generate OH• through the tricarboxylic acid cycle, a transient depletion of NADH, destabilization of iron sulfur clusters, and a stimulation of the Fenton reaction (1). Since OH• are the most powerful oxidizing agent in living cells and have a half-life of nanoseconds (24), cell death could result from the cumulative effect of oxidizing various classes of cellular molecules and macromolecules. However, based on the insights we gained into the mechanistic basis of DinB overproduction cytotoxicity, we hypothesized that, instead, the oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool is specifically responsible for much of the death caused by bactericidal antibiotics.

To test this hypothesis, we overproduced MutT in E. coli and treated with representatives of the three different classes of antibiotics that increase OH•: ampicillin (β-lactam), norfloxacin (quinolone), and kanamycin (aminoglycoside). Strikingly, simply overproducing MutT was sufficient to reduce the sensitivity of E. coli cells to killing by all three drugs, consistent with the hypothesis that oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool underlies much of the cytotoxicity of bactericidal antibiotics (Fig. 2A and S4A). Similarly, over-production of RibA, an alternative 8-oxo-dGTP sanitizer (25), was also sufficient to reduce sensitivity to killing by ampicillin and norfloxacin (Fig. 2B). The inability for RibA to reduce the sensitivity of cells to kanamycin (Fig. 2B) is probably the consequence of the block to protein synthesis caused by kanamycin coupled with the inherent instability of the RibA protein, which results in a substantial reduction of RibA protein levels after addition of the drug (Fig. S5). In contrast, overproduction of NudB, a nucleotide sanitizer that preferentially hydrolyzes 8-OH-dATP in vitro and has only a two-fold effect on mutation rate when over-expressed in a ΔmutT mutant (26, 27), did not affect antibiotic sensitivity (Fig. 2C).

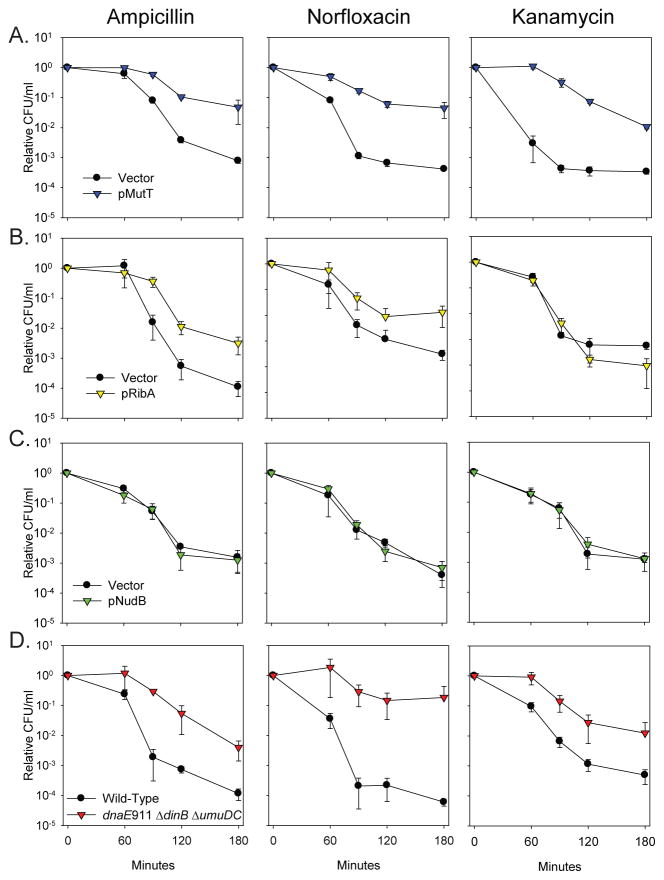

Fig. 2.

The sensitivity of wild-type E. coli cells to killing by ampicillin, norfloxacin, and kanamycin is reduced when incorporation of 8-oxo-dG is minimized. A. Overproduction of the 8-oxo-dGTP sanitizer MutT (blue) in wild-type MG1655 cells was sufficient to significantly reduce the sensitivity of cells to the bactericidal effects of all three classes of drugs compared to the vector control (black). B. Overproduction of the alternative 8-oxo-dGTP sanitizer RibA (yellow) in MG1655 cells is also sufficient to reduce the sensitivity of cells to ampicillin and norfloxacin, but not kanamycin, probably due to its instability (Fig. S5). C. Overproduction of the 8-OH-dATP sanitizer NudB (green) does not reduce the antibiotic sensitivity. D. A mutant strain which lacks the two Y-family DNA polymerases, and expresses an anti-mutator replicative polymerase (dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC) strain (red) is more resistant to killing by bactericidal antibiotics than wild-type cells (black).

The amount of 8-oxo-dG incorporated into DNA is influenced by a combination of the levels of 8-oxo-dGTP in the conditions being examined and the levels and characteristics of the individual polymerases that are present. To gain insights into which of the E. coli polymerases might be contributing to cell death from bactericidal antibiotics by incorporating 8-oxo-dG into DNA, we tested the effect of mutating each polymerase on ampicillin cytotoxicity (Fig. S6). Deletion of ΔdinB (DNA Pol IV) and ΔumuDC (DNA Pol V) reduced killing by ampicillin suggesting that these two polymerases both contribute to ampicillin sensitivity, whereas mutations of polA (DNA Pol I) or polB (DNA Pol II) had no effect. The essential replication DNA polymerase Pol III is also involved in 8-oxo-dG incorporation since an anti-mutator allele of the catalytic subunit (dnaE911), which decreases the mutation frequency of a ΔmutT strain (28), also reduced ampicillin cytotoxicity (Fig. S6). We then generated and tested a dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC triple mutant, and observed a striking reduction in sensitivity to all three classes of antibiotics (Fig. 2D and S4B), consistent with Pol III, Pol IV, and Pol V incorporating more 8-oxo-dG than the cell can handle.

We hypothesized that the action of these polymerases under the conditions of elevated OH• caused by the antibiotics could lead to increased 8-oxo-dG incorporation and hence a lethal MutM/MutY-dependent DSB, as with DinB overproduction. We therefore treated a ΔmutM ΔmutY strain with the three different classes of antibiotics and, as anticipated, observed a significant decrease in killing consistent with the action of these base excision repair enzymes resulting in DSBs (Fig. 3A and S4C).

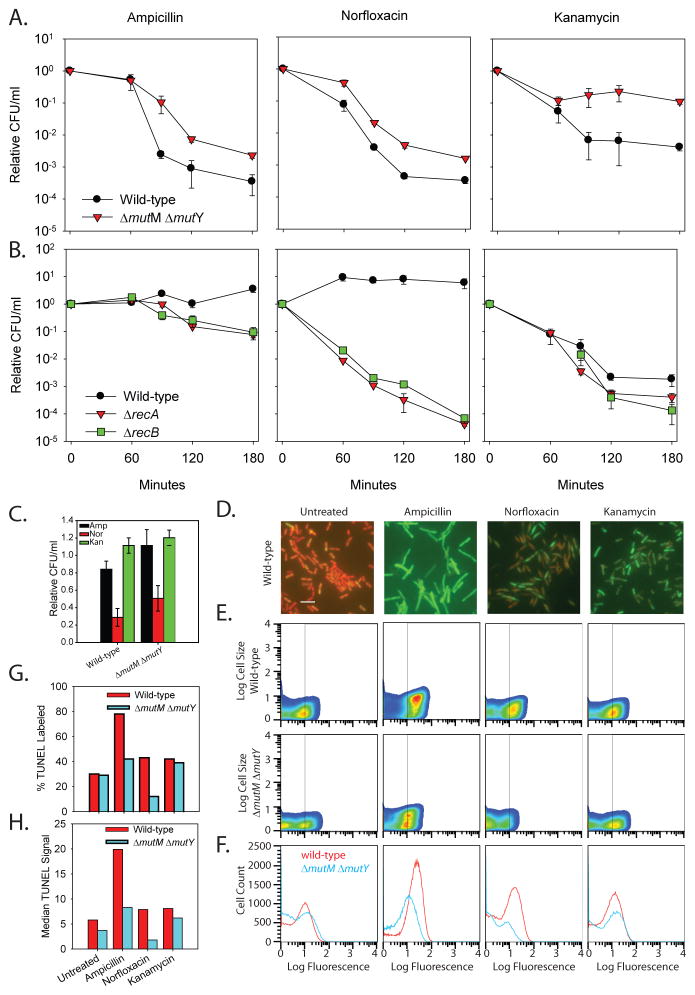

Fig. 3.

Evidence that bactericidal antibiotics cause lethal DSBs. A. A ΔmutM ΔmutY strain is less sensitive than wild-type cells to bactericidal antibiotic killing. B. Deletion of ΔrecA and ΔrecB sensitizes cells to killing by bactericidal antibiotics. Relative CFU/ml of wild-type (black), ΔrecA (red), and ΔrecB (green) cells treated with 2 μg/ml ampicillin, 25 ng/ml norfloxacin, and 3 μg/ml kanamycin. C. Neither ampicillin nor kanamycin treatments for 30 minutes significantly reduce the number of viable wild-type or ΔmutM ΔmutY cells. Norfloxacin treatment for 30 minutes results in a reduction in viable cell number for both wild-type (29% survival) and ΔmutM ΔmutY cells (51% survival). D. Representative fields of wild-type cells after 30 minutes of treatment. Cells containing a DSB (TUNEL positive; green) were overlaid on the propidium iodine staining of all cells (red). Bar = 5 μM. E. Pseudocolor plot of cell size versus TUNEL fluorescence for untreated and treated wild-type and ΔmutM ΔmutY cells at 30 minutes. The vertical line at 10 fluorescence units is the cutoff of TUNEL positive cells which results in 30% of untreated wild-type cells being TUNEL positive consistent with our microscopy results (ca. 25% TUNEL positive: 81 green/292 cells). The number of TUNEL positive wild-type cells increases after antibiotic treatment (top), and ΔmutM ΔmutY cells (bottom) have fewer TUNEL positive cells compared to wild-type. Both cell size (forward scatter) and fluorescence signal (TUNEL signal) are in arbitrary units (A.U.). F. Cell histograms of wild-type (red) and ΔmutM ΔmutY (blue) TUNEL stained cells suggest that ΔmutM ΔmutY cells have fewer dsDNA breaks. G. The percent positive TUNEL labeled cells (≥10 A.U.) determined in panel E is plotted for both wild-type (red) and ΔmutM ΔmutY (blue). H. Plot of the median TUNEL signal for the wild-type and ΔmutM ΔmutY populations shown in panel F.

Deletion of ΔrecA, which prevents DSB repair, has previously been shown to sensitize cells to antibiotics (1). To test if the DSBs generated are repaired by the major RecA-dependent RecBCD pathway, we introduced a ΔrecB mutant allele into cells and tested its effect on antibiotic cytotoxicity. The ΔrecB mutant displayed approximately the same sensitivity as a ΔrecA deletion, consistent with the hypothesis that the RecBCD pathway is utilized to repair the DSBs that are generated as a consequence of 8-oxo-dG incorporation (Fig. 3B).

To further support our hypothesis that DSBs, many of which are MutM/MutY dependent, are responsible for bactericidal cell death rather than being the result of DNA degradation in dead cells, we utilized the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP end labeling (TUNEL) assay. The TUNEL assay covalently attaches a fluorescent molecule to the 3′ terminus of a DNA molecule and, thus, can be used to directly measure DSBs. Thirty minutes after antibiotic treatment of wild-type cells, a time at which little cell death has occurred (Fig. 3C), we observe a qualitative increase in TUNEL positive cells when analyzed by microscopy (Fig. 3D and Fig. S7). We then quantified the number of TUNEL positive cells in wild-type and ΔmutM ΔmutY populations after antibiotic treatment via flow cytometry (Fig 3E and G) and observed MutM/MutY-dependent DSBs. Moreover, the median TUNEL signal for the ΔmutM ΔmutY strain is less than that of wild-type cells after treatment with antibiotics (Fig. 3F and 3H). Collectively, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that bactericidal antibiotics lead to cell death largely by increasing the number of DSBs, a significant fraction of which are MutM/MutY-dependent.

Extension of Common Mechanism Model

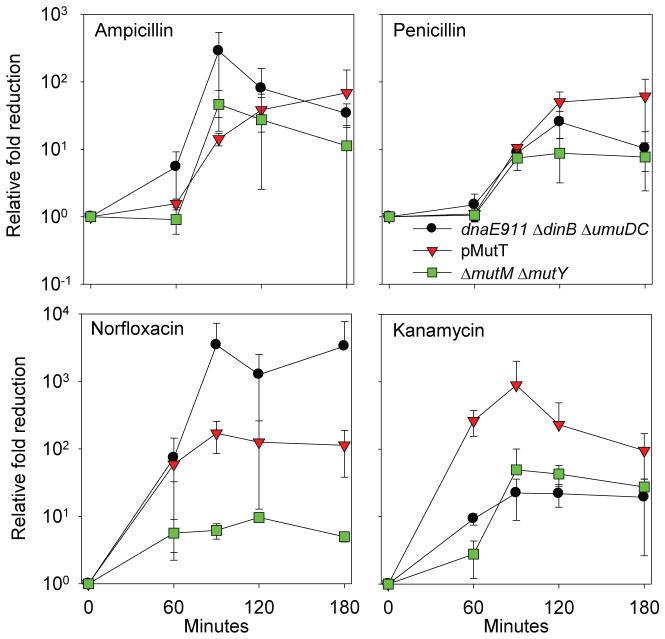

Based on the data described above, we are able to extend the model for a common mechanism of cell death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Instead of generalized oxidative damage resulting in cell death, oxidation of the guanine nucleotide pool to 8-oxo-guanine results in several lethal outcomes. The approximately equal degree of protection from killing by β-lactams due to MutT overproduction, dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC, and ΔmutM ΔmutY (Fig. 4) suggests that a significant portion of the bactericidal effect of β-lactams is due to MutM/MutY-mediated DSBs that are a consequence of Pol III, Pol IV and Pol V incorporating 8-oxo-dG lesions into the daughter strand during replication (Fig. S8). Penicillin, a β-lactam bactericidal antibiotic, was the first antibiotic described and was thought to kill cells primarily and specifically via inhibition of cell wall synthesis (23). It is noteworthy, that our results suggest oxidation of guanine nucleotides also contributes to cell death by penicillin (Fig. 4), thus providing a new insight into the mechanism of action of the oldest known antibiotic. The approximately similar degrees of protection from killing by norfloxacin due to MutT overproduction and dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC indicate that an analogous mechanism is responsible for its bactericidal effects. However, the lesser degree of protection afforded by ΔmutM ΔmutY (Fig. 4) suggests that DNA gyrase inhibition additionally contributes to the DSBs caused by 8-oxo-dG incorporation (Fig. S8).

Fig. 4.

Relative protective effect against killing due to MutT overproduction, mutation of three DNA polymerases (dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC), and ΔmutM ΔmutY for β-lactams, norfloxacin, and kanamycin suggests oxidation of guanine mediates bactericidal antibiotic-induced cell death. For β-lactams (ampicillin and penicillin), a similar fold rescue is observed for all three conditions. For norfloxacin, a similar degree of protection is afforded by MutT overproduction and mutation of the DNA polymerases, but a lesser degree of protection is observed for ΔmutM ΔmutY. For kanamycin, the greater fold rescue associated with MutT overproduction compared to dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC and ΔmutM ΔmutY suggests oxidation of the guanine to 8-oxo-rGTP is additionally contributing to cell death.

This 8-oxo-dG-dependent DSB mechanism accounts for some of the bactericidal effects of kanamycin, as there is protection from killing by dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC and ΔmutM ΔmutY. However, our observation that the degree of protection caused by MutT overproduction is larger (Fig. 4) than that conferred by dnaE911 ΔdinB ΔumuDC or ΔmutM ΔmutY, together with the relatively modest increases in sensitivity conferred by the ΔrecA and ΔrecB mutants, suggests that an additional mechanism of cell killing is involved in the case of kanamycin. The reduced involvement of the 8-oxo-dG-dependent DSB mode of killing may, in part, be due to its translational inhibitory effects preventing the synthesis of SOS-regulated proteins, including the dinB- and umuDC-encoded DNA polymerases, other proteins required for stress responses, and antitoxins thereby leading to activation of their cognate toxins. Nevertheless, the strong suppression of kanamycin cytotoxicity by MutT overproduction suggests that, in addition to their known direct effect on the ribosome (29), a substantial amount of the cytotoxicity caused by aminoglycosides in vivo is due to oxidation of guanine nucleotides.

An intriguing hypothesis is that the protective effect of MutT overproduction is due to MutT’s ability to sanitize the guanine ribonucleotide pool (8-oxo-rGTP and 8-oxo-rGDP) (30, 31) as well as the guanine deoxynucleotide pool (Fig S8). RNA polymerase is proficient at using 8-oxo-rGTP as a substrate, incorporating 8-oxo-rG into transcripts at one tenth the rate it incorporates rG (30). These potentially altered transcripts could lead to mistranslated proteins, which is consistent with the previous observation that ΔmutT strains exhibit higher levels of protein carbonylation (32), a consequence of protein mistranslation. Moreover, the effect of 8-oxo-rGTP on protein mistranslation would be exacerbated by its misincorporation into rRNA and tRNA, which would be expected to further reduce the fidelity of protein synthesis. This potential for kanamycin-induced 8-oxo-rGTP-dependent mistranslation of cell envelope proteins could, in turn, cause more membrane alterations leading to increased drug up-take and further stimulation of the OH• radical pathway through membrane stress two-component systems (Cpx) and changes in metabolic function (Arc) (29). Thus, kanamycin treatment could potentially result in a catastrophic cycle of mistranslation driven by 8-oxo-rGTP.

It is also possible that 8-oxo-rGTP and 8-oxo-rGDP contribute to cell killing by interfering with the functioning of GTPases, thirteen of which are conserved in 75% of bacteria and most of which have critical functions in translation (33). For example, the reduced ability of the essential E. coli GTPase, Era, to hydrolyze 8-oxo-rGTP, compared to GTP (Fig. S9), could alter the ratio between its GTP- and GDP-bound forms. In addition, oxidation of (p)ppGpp could potentially interfere with the proper operation of the bacterial stringent response (34). Such bactericidal effects stemming from oxidation of the guanine ribonucleotide pool likely contribute to bactericidal effects of ampicillin and norfloxacin as well, but they appear to be less important than those mediated by the oxidation of the guanine deoxyribonucleotide pool.

Broad Implications

Our model has two broad implications for the effectiveness of bactericidal antibiotics. First, in addition to a bacterial cell’s intrinsic permeability to a drug and its ability to excrete it through drug pumps, our results suggest that its complement of DNA polymerases, DNA repair enzymes, and nucleotide sanitizers such as MutT could also play a role in a bacterium’s intrinsic susceptibility to antibiotics. It is known that E. coli cells maintain a constant level of MutT after antibiotic stress (1) suggesting that a fitness cost maybe associated with up-regulation of nucleotide sanitizers, perhaps decreasing mutagenesis that could lead to multidrug resistance (35). Second, the enhanced utilization of 8-oxo-guanine in nucleic acid transactions resulting in bacterial cell death could provide an avenue for identifying druggable targets for use as antimicrobial adjuvants. In the last few decades only a handful of new classes of antibiotics have been introduced, leading many to lament that the antibiotic pipeline is broken (36, 37). Although, new antimicrobial therapies are needed, adjuvants have the potential of extending the usefulness of current therapies. Our results suggest, for example, that bactericidal antibiotics could be potentiated by targeting proteins involved in repairing double-stranded DNA breaks, e.g., inhibiting RecA or RecBCD or by influencing the incorporation of 8-oxo-guanine into the DNA and RNA or the consequences of this incorporation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stephen Bell and Dr. Dennis Kim for use of equipment and Dr. Susan Lovett for strains. This work was supported by NIH Grants RO1 CA021615 (to G.C.W.), F32 GM079885 (to J.J.F.), DP1 OD003644 (to J.C.C.), P30 ES002019 (to the MIT Center for Environmental Sciences) as well as the HHMI. G.C.W. is an American Cancer Society Professor.

References and Notes

- 1.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B, Lawrence CA, Collins JJ. Cell. 2007;130:797. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies BW, et al. Molecular cell. 2009;36:845. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchida K, et al. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Indiani C, Langston LD, Yurieva O, Goodman MF, O’Donnell M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901403106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imlay JA, Chin SM, Linn S. Science. 1988;240:640. doi: 10.1126/science.2834821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novogrodsky A, Ravid A, Rubin AL, Stenzel KH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:1171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.4.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Repine JE, Fox RB, Berger EM. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Touati D, Jacques M, Tardat B, Bouchard L, Despied S. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2305. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2305-2314.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haghdoost S, Sjolander L, Czene S, Harms-Ringdahl M. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:620. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neeley WL, Essigmann JM. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:491. doi: 10.1021/tx0600043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katafuchi A, et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:859. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarosz DF, Godoy VG, Delaney JC, Essigmann JM, Walker GC. Nature. 2006;439:225. doi: 10.1038/nature04318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedberg EC, et al. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. 2. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tassotto ML, Mathews CK. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pursell ZF, McDonald JT, Mathews CK, Kunkel TA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2174. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rotman E, Kuzminov A. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6976. doi: 10.1128/JB.00776-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward JF, Evans JW, Limoli CL, Calabro-Jones PM. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1987;8:105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner DJ, Ward JF. Int J Radiat Biol. 1992;61:737. doi: 10.1080/09553009214551591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonura T, Town CD, Smith KC, Kaplan HS. Radiat Res. 1975;63:567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner J, Fujii S, Gruz P, Nohmi T, Fuchs RP. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:484. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujikawa K, et al. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pankey GA, Sabath LD. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:864. doi: 10.1086/381972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh C. Nature. 2000;406:775. doi: 10.1038/35021219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodell B, et al. J Biotechnol. 1997;53:133. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi M, et al. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hori M, Fujikawa K, Kasai H, Harashima H, Kamiya H. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:33. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hori M, et al. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1087. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fijalkowska IJ, Dunn RL, Schaaper RM. Genetics. 1993;134:1023. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Wierzbowski J, Cottarel G, Collins JJ. Cell. 2008;135:679. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taddei F, et al. Science. 1997;278:128. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito R, Hayakawa H, Sekiguchi M, Ishibashi T. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6670. doi: 10.1021/bi047550k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dukan S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100422497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caldon CE, Yoong P, March PE. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J, Xie J. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:297. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohanski MA, DePristo MA, Collins JJ. Molecular cell. 2010;37:311. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper MA, Shlaes D. Nature. 2011;472:32. doi: 10.1038/472032a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morel CM, Mossialos E. BMJ. 2010;340:1115. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.