Abstract

The prevalence of epidermal conditions in a small population of coastal bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Monterey Bay was evaluated between 2006 and 2008. Five different skin condition categories were considered, including Pox-Like Lesions, Discoloration, Orange Film, Polygon Lesions, and Miscellaneous Markings. Of 147 adults and 42 calves photographically examined, at least 90 and 71%, respectively, were affected by at least one or multiple conditions. Pox-Like Lesions were the most prevalent, affecting 80% of the population, including adults and calves. This condition warrants the most urgent investigation being possibly indicative of the widespread presence of poxvirus or a similar pathogen in the population. In view of the high number of individuals affected, standard monitoring of the health status of Monterey Bay bottlenose dolphins is considered imperative. Discoloration was strongly associated with Pox-Like lesions. Orange Films were likely an epifaunal infestation caused by diatoms, which have been documented in other cetacean species. Polygon Lesions, a newly described category, could be the result of infestation by barnacles of the genus Cryptolepas. Miscellaneous Markings were variable in appearance and may not have the same causative factor. Although none of the proposed etiologies can be confirmed without appropriate clinical tests, recognizing common visible characteristics of the conditions could aid in preliminary comparisons across populations and individuals.

Keywords: Epidermal conditions, Bottlenose dolphin, Tursiops truncatus, California, Health, Lesions

Introduction

Epidermal diseases are well documented in many cetacean species (Simpson et al. 1958; Greenwood et al. 1974; Smith et al. 1983; Van Bressem et al. 1993; Dierauf and Gulland 2001; Pettis et al. 2004; Brownell et al. 2007). The pathogens involved are varied and generally include viruses, bacteria, fungi and, occasionally, ciliated protozoans, many naturally occurring in the marine environment (Van Bressem et al. 2007). Infections are caused by a breakdown of the host’s defense mechanisms such as the shear-resistant gel at the surface of dolphin skin (Meyer et al. 2008), or the enzymes and peptide groups found in cetacean epidermis (Meyer and Seegers 2004). Pre-existing lesions or infections may provide routes of entry for a variety of pathogens (Schulman and Lipscomb 1999; Van Bressem et al. 2007).

The wide variety of skin conditions which affect bottlenose dolphin populations worldwide has been linked to environmental factors such as water salinity and temperature, and to anthropogenic factors such as pollution and contaminants (Wilson et al. 1999). Contaminants in particular, through the process of bio-magnification, can accumulate at levels highly toxic to cetaceans and depress the immune system, exacerbating the severity of clinical signs (DeGuise et al. 1995; Levin et al. 2007).

California coastal bottlenose dolphins are part of a single stock that inhabits the near-shore strip just beyond the surf zone between San Quentin, Mexico, and San Francisco, California (Feinholz 1996; Defran and Weller 1999). Individual animals may reside in a geographically small coastal area for a period of months to years and then move either north or south, shifting their distribution several hundred kilometers (Wells et al. 1990; Feinholz 1996; Defran and Weller 1999). These movements expose them to a variety of water temperatures and oceanographic conditions. The population is small (300–500 individuals) according to recent estimates (Dudzik et al. 2006). The Optimal Sustainable Population (OSP) is not known, and there is no indication of a trend in abundance (NMFS 2008).

By occupying a habitat so close to the land–sea interface, California coastal bottlenose dolphins feed in areas heavily impacted by anthropogenic input; they are also a top predator in the coastal zone, with the potential for bio-accumulating contaminants (Kannan et al. 1989, Ross et al. 1996). The long-term monitoring of bottlenose dolphin skin conditions along the California coast is a potentially important indicator of ecosystem health.

We summarize the types of skin conditions found in the bottlenose dolphins using the waters of Monterey Bay, which is an important core area for the California coastal stock (Feinholz 1996; D. Maldini unpublished data) and where over 300 animals have been documented since 1990 (D. Maldini unpublished data). Monterey Bay is also part of the larger Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and an assessment of coastal dolphins’ health parameters is important in the context of managing the sanctuary’s ecosystem.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

Monterey Bay is located along the central California coastline between Santa Cruz to the north and Point Piños to the south (latitude: 36°37′N to 36°56′N). The bay is within the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and is California’s second largest bay. Its distinguishing feature is the presence of the deepest and largest submarine canyon along the west coast of North America, which bisects the bay and brings nutrient-rich deep waters within a mile from shore, supporting extensive fish, invertebrate, seabird, and marine mammal populations. The bay is approximately 37 km long, north to south, and 16 km wide, east to west (Breaker and Broenkow 1994).

The study area included waters between the shoreline and 1 km offshore with depths ≤20 m, which is the limit of coastal bottlenose dolphin distribution in Monterey Bay (Feinholz 1996; Defran and Weller 1999). Surveys of the entire coastal strip were conducted between Monterey and Santa Cruz. This area is strongly influenced by surf conditions and rip currents, and its waters are generally turbid.

Data Collection

Boat-based photo-identification surveys for California coastal bottlenose dolphins were conducted in Monterey Bay by traveling at an average speed of 18 km h−1 parallel to the shoreline just outside the surf zone (≤500 m). Surveys covered 52 km of coastline from Monterey to Santa Cruz and were only conducted in ideal conditions (Beaufort ≤2). Dolphins were photographed using digital technology (Canon 30D and 40D and Canon 100–400 mm Image Stabilized zoom lens), and pictures of the side of the dorsal fin and body were taken. Each dolphin school encountered was followed until all dolphins were photographed at least once, unless weather conditions or evasion by dolphins ended observations. All images were compiled into a photo-identification catalog with individual dolphins identified from distinctive markings and scars (Feinholz 1996). Images were cataloged using ACDSee© software and by using techniques modified from Mazzoil et al. (2004).

Evaluation of Photographs

All images in our photo-identification catalog were analyzed for clarity, focus, exposure, and parallax. An image was classified as excellent for the purpose of detecting the presence of a skin condition if: (1) the image was in focus; (2) at least the entire dorsal fin and the area of the body immediately below were visible; (3) the animal occupied at least ¾ of the frame. All images that met these criteria were selected for each known dolphin in the catalog.

The visible areas of the body were visually inspected for the presence or absence of skin conditions classified based on their appearance. For each photo, the types of condition found and their locations were recorded. Body scars that clearly suggested injury or trauma (i.e., nicks, bleeding wounds, rake-marks, and clearly discernable bite marks) were not included in the classification. Scars and marks potentially acquired as a result of aggressive interactions can often be inferred from matching them to the dentition of predators or conspecifics (McCann 1974; Heithaus 2001), and injuries from boat strikes or nets are also identifiable (George et al. 1994). To ensure consistency, each photo was evaluated by two independent observers.

Skin Condition Categories

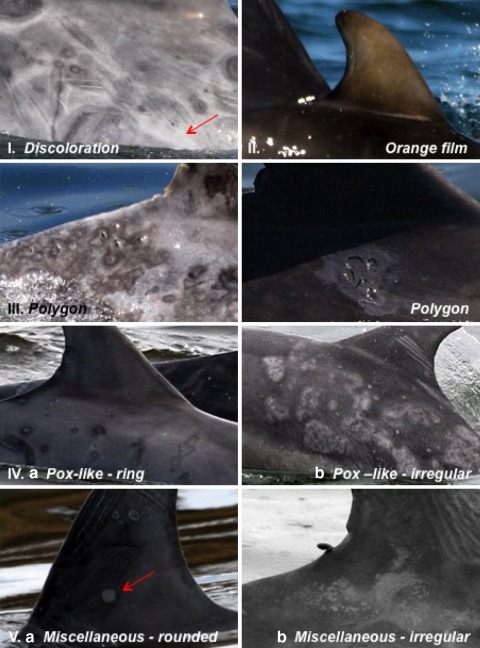

Skin conditions were assigned to five categories (Fig. 1):

Discoloration: This category presented as a whitish patina generally resulting in lighter than average coloration of the skin. It could be either found in patches (as large or larger than a human hand) or evenly widespread over large areas of the body. This type of lesion, as described, is new to the literature. However, Wilson et al. (1997) and Bearzi et al. (2009) included similar lesions in the category ‘pale lesions’. The category appeared to us distinct enough to warrant a new classification.

Orange Film: This category combined ‘orange hue’ and ‘orange patches’ described by Wilson et al. (1997) and included both orange or rusty-colored films over the skin either uniformly covering the body or found in dense but small patches on dorsal fin and/or body.

Polygons: These lesions presented as shallow depressions of the skin, generally with a hexagonal or polygonal shape and ≤1 cm in diameter. They were characterized by the presence of a dark pinhole in the middle of the depression and occurred either in clusters or isolated on the body and/or dorsal fin. Bearzi et al. (2009) classified these lesions as the ‘lunar lesions’ described in Wilson et al. (1997), but we found them to be different enough to warrant a new category. This type of lesion is new to the literature.

‘Pox-Like’ Lesions: This category comprised both ring and irregular-shaped lesions (tattoo lesions) similar to those described by other authors in cetaceans affected by poxvirus (family Poxviridae) (Geraci et al. 1979; Van Bressem et al. 1999). The size and the coloration of these lesions were found to be variable, ranging from completely hyperpigmented, to pale and dark-fringed, and vice versa. Lesions were either completely raised, had a raised rim, or were almost flush. In some cases, ringed lesions were hyperpigmented in the middle. They were found either isolated or evenly distributed on dorsal fin, body, or both. Despite the definition ‘Pox-Like’, we do not imply a known etiology for these lesions, but simply emphasize their similarity in appearance to lesions described as such by other authors.

Miscellaneous Markings: Included in this category were well-defined but variably shaped markings, flush with the skin and of contrasting color. They could be round or of irregular shape. They were present on body and/or dorsal fin, mostly isolated and, occasionally, in clusters.

Fig. 1.

Examples of skin condition categories found in the Monterey Bay bottlenose dolphin population. From top right: I Discoloration, II Orange Film, III Polygons, IV Pox-Like Lesions including (a) ring and (b) irregular lesions; and V Miscellaneous Markings including (a) rounded and (b) irregular-shaped markings. (Photos: M.P. Cotter)

Prevalence of each condition was expressed as a proportion and either z-statistics or Chi Square were used to compare either two or multiple categories with α = 0.005. To establish strength of association or co-occurrence of different conditions, the association coefficient (AC) was calculated as:

|

where J is the number of times two conditions were found together on the same animal, and A and B are the number of times each of the two conditions was recorded for all animals. AC < 0.3 was considered a weak association for the purpose of this study.

Results

Field Effort

Between August and October 2006–2008, 88 coastal surveys were conducted in Monterey Bay: 34 in 2006, 31 in 2007, and 31 in 2008. All surveys were conducted in ideal conditions (Beaufort ≤2). Total effort was 364.4 h and 2,206.94 km2 for the 3 years combined. Coastal dolphins were encountered in all of the surveys and the effort resulted in the photo-identification of 212 adult bottlenose dolphins and of 42 calves associated with a single adult female.

Skin Conditions

We found at least one photo that matched optimal quality criteria for 147 adults (52 females, 46 males, and 43 of unknown sex) and all the calves. One hundred and thirty-three adults (90%) and 30 calves (71%) were affected by one or multiple (81%) skin conditions. The five types of lesions (Table 1; Fig. 1) in the population were in the following overall proportions, listed by prevalence: Pox-Like Lesions (80%), Discoloration (48%), Orange Film (42%), Miscellaneous Markings (25%), and Polygons (5%). The prevalence of different conditions was not significantly related to sex (Yates corrected z test for each condition); therefore, adults were pooled for comparison with calves. The difference in proportion of animals affected overall between adults and calves was significant (Yates corrected z = 2.670; p = 0.008). Prevalence of Pox-Like Lesions was significantly higher (Yates corrected z = 3.669; p ≤ 0.001) in adults (84%) than in calves (43%). Orange Film was significantly more prevalent in calves (62%) than in adults (22%). Discoloration and Polygons were not found in calves.

Table 1.

Prevalence, by age/sex group, of different types of skin conditions in Monterey Bay coastal bottlenose dolphins

| Age/sex | Disc | Orange film | Polygon | Pox-like | Misc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of individuals | 61 | 58 | 6 | 142 | 31 |

| Males | 0.66 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.87 | 0.19 |

| Females | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.30 |

| Calves | 0.00 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.12 |

Disc discoloration, misc miscellaneous

One percent of adults presented all five conditions simultaneously, but the majority had either two (41%), one (28%), three (25%) or four (5%). Calves had mostly one (60%) or two (33%) simultaneous conditions. Both males and females were similar in the number of condition-types found simultaneously on the body (χ2 = 1.071; df = 2; p = 0.585) and the pooled adult population differed significantly from calves (χ2 = 25.641; df = 2; p < 0.001). All affected calves started showing skin conditions during their second or third year.

Round and irregularly shaped Pox-Like Lesions occurred together in all but two individuals. Pox-Like Lesions had strong association with Polygons (AC = 1.00), Discoloration (AC = 0.66), and with Orange Film (AC = 0.45). Discoloration was strongly associated with Orange Film (AC = 0.41). All other associations were weak.

Discussion

The prevalence of visible skin conditions in California coastal bottlenose dolphins is high. Whether this is significant in terms of population health cannot be established with certainty until a proper diagnostic study, using samples from live skin tissues, is performed. Nonetheless, the general appearance of some skin conditions can be used to assess the likelihood that they are indicative of a particular etiology.

Although Wilson et al. (1999) used different categorizations to evaluate skin conditions, their results indicated a similarly high incidence within geographically separated bottlenose dolphin populations, incidence ranging between 67% in Florida and 100% in England. Our study population falls within the higher values (90%) found by Wilson and colleagues, supporting the hypothesis that skin conditions are a geographically widespread phenomenon in bottlenose dolphins. The variability in prevalence and appearance of these conditions may depend on local environmental variables such as water temperature and salinity, and/or the presence of other ‘stressors’ such as water contamination (Wilson et al. 1999).

California coastal bottlenose dolphins in Monterey Bay had equally prevalent Pox-Like Lesions in both sexes, but more adults than calves were affected. True pox lesions may be indicative of environmental stress and/or generally poor health (Geraci et al. 1979), but may not affect overall survival (Sweeney and Ridgway 1975; Geraci et al. 1979; Van Bressem et al. 1993; Van Bressem and Van Waerebeek 1996). Van Bressem et al. (1993) suggested calves may be protected from poxvirus through maternal immunity. However, at least 43% of calves in our study presented the condition and started showing signs during their second or third year. It is unclear how this age-transition plays a role, but changes in passive transfer of immunity from dam to calf associated with weaning should be considered.

Poxvirus has been well documented in seals and sea lions (Wilson et al. 1969; Wilson et al. 1972; Becher et al. 2002; Muller et al. 2003), which occupy the same coastal areas as bottlenose dolphins in California, and is known to occur in cetaceans (Flom and Hoek 1979; Geraci et al. 1979; Van Bressem et al. 1993, 1999; Brownell et al. 2007). The coastal environment in California, and in Monterey Bay in particular, is of concern because of high contaminant loads and general levels of pollutants (Hartwell 2008). Environmental contaminants have been linked to marine mammal diseases (Aguilar and Borrell 1994; Ross et al. 1996), and high contaminant levels have been associated with higher prevalence of tattoo lesions (Pox-Like Lesions) in dolphins in some studies (Van Bressem et al. 2003). However, no direct link between contaminants (cause) and skin lesions (effect) has been verified.

Discoloration of the body either uniformly or in patches was the second most prevalent skin condition and it was limited to adults with no difference between sexes. This supports the hypothesis that discoloration may be acquired over time. One possibility is that this condition is the result of repeated scarring from trauma of a type not easily identifiable at first inspection (obvious scarring was excluded from analysis in our methodology), rather than disease. In this case, the amount of scarring may indicate social rank and the intensity of aggressive interactions an animal has been exposed to over its lifetime (Scott et al. 2005). We are further investigating this possibility through long-term monitoring of the evolution of traumatic injuries of known individuals. At this point, our data is not sufficient to substantiate this hypothesis. However, given the association of Discoloration to Pox-Like Lesions, we cannot either exclude it being the result of healing from repeated exposure to a skin condition or some manifestation of a related condition.

Orange Films and patches were the third most prevalent condition. Diatoms or other epifauna embedded in the skin are the most likely cause of such coloration pattern. A variety of diatom taxa have been identified on cetacean skin (Hart 1935; Usachev 1940; Okuno 1954; Nemoto 1956; Holmes et al. 1993). Two in particular, Bennettella (previously Cocconeis) ceticola and Epipellis oiketis are non-planktonic forms found exclusively on the skin of cetaceans (Holmes and Nagasawa 1995). At least 15 different species of diatoms have been observed on cetaceans in Monterey Bay (Morejohn 1980), including E. oiketis (Holmes 1985). Some of these diatoms thrive in waters 13°C or colder (Nemoto et al. 1980), and infestations tend to disappear in warmer waters. A comparison with data from Bearzi et al. (2009) for the same population of bottlenose dolphins while in Santa Monica Bay, California (approximately 400 km south of Monterey Bay) indicates a much lower prevalence of orange films and patches in the warmer waters of southern California than in our study area. Temperatures in Santa Monica Bay range from 13.8°C in January to 20°C in August, while Monterey Bay ranges from 11.7 to 15.6°C.

Blood flow to the skin may be reduced in colder temperatures slowing down regeneration within the epidermis (Feltz and Fay 1996). Although Holmes et al. (1993) suggest that bodily contact is the most likely form of transfer for epifauna, calves appear to be particularly susceptible, suggesting the barrier provided by adult skin might not be completely developed in calves. It is possible that epifaunal infestations are a vector for pathogens or parasites and that calves with widespread epifaunal infestations may be more prone to be affected by other skin conditions.

Miscellaneous Markings, the fourth type of skin condition documented, are difficult to evaluate as a group, probably because they are from various origins. Some may represent the remnants of healed injuries (but not easily recognizable as such upon visual inspection), or difficult to classify forms of the already described conditions. They were poorly associated with other lesions suggesting they may not be related. These types of markings need further examination.

Polygon Lesions are an interesting case study affecting only six adults in the population. The hole in the middle of the hexagonal crater suggests it may be the attachment site for a barnacle. Ridgway (pers. comm.) reported captive bottlenose dolphins in San Diego Bay becoming infested with the barnacle Cryptolepas rhachianecti, previously considered an obligate commensal of the gray whale, Eschrichtius robustus. The same barnacle was documented infesting captive belugas, Delphinapterus leucas in San Diego Bay (Ridgway et al. 1997), and was reported on a killer whale, Orcinus orca, stranded along the southern California coast (Samaras 1989). In all cases the infestation seemed to be related to the presence of gray whales in the area.

Pox-Like Lesions are the most significant condition in this population and the large proportion of animals affected warrants further investigation. Similar conditions in other populations have been linked to bioaccumulation of contaminants to toxic levels in fatty tissues (Reif et al. 2009). Males, who continually accumulate these compounds with age, and calves from first time mothers, who consume their mothers’ life-long contaminant load through milk, are generally found to have higher contaminant loads than females (Addison and Brodie 1987; Borrell et al. 1995; Ross et al. 2000). As adult males and females were found to be equally prone to skin conditions and because some of the calves affected were confirmed to be from veteran mothers (D. Maldini, unpublished data), the potential link to contaminants in our study is weakened. In addition, preliminary information on contaminant loads for this population (T. Jefferson, unpublished data) indicates that, at least for Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), levels in this population are below toxicity. The prevalence of Pox-Like Lesions within the coastal population should be assessed because it could be indicative of other environmental stressors. The long-term health of this population should not be overlooked, especially because the overall coastal California bottlenose dolphin stock is currently estimated at less than 500 animals (Dudzik et al. 2006).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Cyndi Browning, Alessandro Ponzo, and Gary Haskins to the completion of this manuscript. We also would like to thank all Earthwatch volunteers who participated in our project for their help with data entry. We are grateful to Dave Casper, Frances Gulland, and Hendrik Nollens for their suggestions and veterinary expertise. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their pertinent and helpful comments. Partial funding for this study was provided by Earthwatch Institute and by an anonymous donor. Jessica Riggin was supported by the National Science Foundation under the CSU-LSANP Senior Alliance Project (NSF Grant #HRD-0802628).

Biographies

Daniela Maldini

is the President and Chief Scientist of Okeanis, a central California-based non-profit organization dedicated to the study of marine mammals and their role in the marine environment. She is also Adjunct Faculty at Gavilan College in Gilroy California. She has worked around the world focusing her research on social structure, behavior, and conservation biology of cetaceans and other large vertebrates.

Jessica Riggin

is an intern with Okeanis and an undergraduate student at California State University Monterey Bay, Division of Science and Environmental Policy. Her research interests include cetacean behavior, ecology, habitat use, health, and conservation.

Arianna Cecchetti

is an intern with Okeanis and holds an MS in Marine Mammal Science from the University of Wales, Bangor, UK. Her research interests include cetacean ecology, habitat use, pathology, and conservation.

Mark Cotter

is a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth, Department of Biology, and is the Field Director for the California Coastal Dolphin Project. He also manages the photo-identification catalog. His research interests include behavioral ecology and population biology of cetaceans.

Footnotes

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Data were collected under NOAA LOA 877-1831.

Contributor Information

Daniela Maldini, Phone: +1-831-7315002, Email: dmaldini@okeanis.org.

Jessica Riggin, Email: jessica.riggin@gmail.com.

Arianna Cecchetti, Email: ariannacecchetti@gmail.com.

Mark P. Cotter, Email: markpcotter@hotmail.com

References

- Addison RF, Brodie PF. Transfer of organochlorine residues from blubber through the circulatory system in milk in the lactating grey seal, Halichoerus grypus. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 1987;44:782–786. doi: 10.1139/f87-095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar A, Borrell A. Abnormally high polychlorinated biphenyl levels in striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) affected by the 1990–1992 Mediterranean epizootic. Science of the Total Environment. 1994;154:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearzi M, Rapoport S, Chau J, Saylan C. Skin lesions and physical deformities of coastal and offshore common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Santa Monica Bay and adjacent areas, California. Ambio. 2009;38(2):66–71. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-38.2.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher P, Konig M, Muller G, Siebert U, Thiel HJ. Characterization of sealpox virus, a separate member of the parapoxviruses. Archives of Virology. 2002;147:1133–1140. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell A, Block D, Desportes G. Age trends and reproductive transfer of organochlorine compounds in long-finned pilot whales from the Faroe Islands. Environmental Pollution. 1995;88:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(95)93441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaker LC, Broenkow WW. The circulation of Monterey Bay and related processes. Oceanography and Marine Biology. 1994;32:1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, Jr., R.L., C.A. Carlson, B.G. Vernazzani, and E. Cabrera. 2007. Skin lesions on blue whales off southern Chile: possible conservation implications? International Whaling Commission Report SC/59/SH21.

- Defran RH, Weller DW. Occurrence, distribution, site fidelity and school size of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) off San Diego, California. Marine Mammal Science. 1999;15:366–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00807.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dierauf LA, Gulland FMD. CRC handbook of marine mammal medicine. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DeGuise S, Martineau D, Beiand P, Fourniere M. Possible mechanisms of action of environmental contaminants on St. Lawrence beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) Environmental Health Perspectives. 1995;103(4):73–77. doi: 10.2307/3432415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudzik, K.J., K.M. Baker, and D.W. Weller. 2006. Mark-recapture abundance estimate of California coastal stock bottlenose dolphins: February 2004 to April 2005. SWFSC Administrative Report LJ-06-02C, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, 8604 La Jolla Shores Drive, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA, 15 pp.

- Feinholz, D.M. 1996. Pacific coastal bottlenose dolphins in Monterey Bay, California. M.S. Thesis, Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, San Jose State University.

- Feltz TE, Fay FH. Thermal requirements in vitro of epidermal cells from seals. Cryobiology. 1996;3:261–264. doi: 10.1016/S0011-2240(66)80020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flom JO, Hoek EJ. Morphologic evidence of poxvirus in tattoo lesions from captive bottlenosed dolphins. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 1979;15:593–596. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-15.4.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George JC, Philo LM, Hazard K, Withrow D, Carroll GM, Suydam R. Frequency of killer-whale (Orcinus orca) attack and ship collisions based on scarring on bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) off the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Sea stock. Arctic. 1994;47:247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Geraci JR, Hicks BD, St.Aubin DJ. Dolphin pox: A skin disease of cetaceans. Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine. 1979;43:399–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood AG, Harrison RJ, Whitting HW. Functional and pathological aspects of the skin of marine mammals. In: Harrison RJ, editor. Functional anatomy of marine mammals. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 73–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hart TJ. On the diatoms of the skin film of whales and their possible bearing on problems of whale movement. Discovery Reports. 1935;10:247–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell SI. Distribution of DDT and other persistent organic contaminants in canyons and on the continental shelf off the central California coast. Marine Environmental Research. 2008;65:199–217. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heithaus MR. Shark attacks on bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) in Shark Bay, Western Australia: Attack rate, bite scar frequencies, and attack seasonality. Marine Mammal Science. 2001;17:526–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01002.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes RW. The morphology of diatoms epizoic on cetaceans and their transfer from Cocconeis to two genera, Bennettella and Epipellis. British Phycological Journal. 1985;20:43–57. doi: 10.1080/00071618500650061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes RW, Nagasawa S. Bennettella constricta (Nemoto-Holmes) and Bennettella berardii sp. nov. (Bacillariophyceae: Chrysophyta) as observed on the skin of several cetacean species. Bulletin of the National Science Museum Series B. 1995;21:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes RW, Nagasawa S, Takano H. The morphology and geographic distribution of epidermal diatoms of the Dall’s porpoise (Phocoenoides dalli) in the northern Pacific ocean. Bulletin of the National Science Museum, Tokyo, Series B. 1993;19(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan N, Tanabe S, Ono M, Tatsukawa R. Critical evaluation of polychlorinated biphenyls toxicity in terrestrial and marine mammals: Increasing impact of non-ortho and mono-ortho coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls from land to ocean. Archives of Environmental and Contamination Toxicology. 1989;18:850–857. doi: 10.1007/BF01160300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M, Morsey B, Guise S. Non-coplanar PCBs induce calcium mobilization in bottlenose dolphin and beluga whale, but not in mouse leukocytes. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health A. 2007;70:1220–1231. doi: 10.1080/15287390701380898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoil M, McCulloch SD, Defran RH, Murdoch ME. Use of digital photography and analysis of dorsal fins for photo-identification of bottlenose dolphins. Aquatic Mammals. 2004;30:209–219. doi: 10.1578/AM.30.2.2004.209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCann C. Body scarring on cetacean-odontocetes. Scientific Report Whales Research Institute. 1974;26:145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer W, Seegers U. A preliminary approach to epidermal antimicrobial defense in the Delphinidae. Marine Biology. 2004;144:841–844. doi: 10.1007/s00227-003-1256-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, W., J.E. Kloepper, and L.G. Fleisher. 2008. Demonstration of B-glucan receptors in the skin of aquatic mammals—A preliminary report. European Journal of Wildlife Research. doi:10.1007/s10344-008-0173.

- Morejohn GV. The natural history of the Dall’s porpoise in the North Pacific Ocean. In: Winn HE, Olla BL, editors. Behaviour of marine animals. New York: Plenum Press; 1980. pp. 45–83. [Google Scholar]

- Muller G, Groters S, Siebert U, Rosenberger T, Driver J, Konig M, Becher P, Hetzel U, Baumgartner W. Parapox infection in harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) from the German North Sea. Veterinary Pathology. 2003;40:445–454. doi: 10.1354/vp.40-4-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T. On the diatoms of the skin film of whales in the northern Pacific. Scientific Report of the Whales Research institute. 1956;11:97–132. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Best PB, Ishimaru K, Takano H. Diatom films on whales in South African waters. Scientific Report of the Whales Research institute. 1980;32:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). 2008. California coastal bottlenose dolphin stock assessment report. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/sars/po2008dobn-caco.pdf. Accessed 24 March 2010.

- Okuno H. Electron-microscopical study on Antarctic diatoms (6). Observations on Cocconeis ceticola forming ‘diatom film’ on whale skin. Journal of Japanese Botany. 1954;29:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Pettis HM, Rolland RM, Hamilton PK, Brault S, Knowlton AR, Kraus SD. Visual health assessment of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalena glacialis) using photographs. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 2004;82:8–19. doi: 10.1139/z03-207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reif J, Peden-Adams MM, Romano TA, Rice CD, Fair PA, Bossart GD. Immune dysfunction in Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tusiops truncatus) with lobomycosis. Medical Mycology. 2009;47(2):125–135. doi: 10.1080/13693780802178493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway SH, Lindner E, Mahoney KA, Newman WA. Gray whale barnacles Cryptolepas rhachianecti infest white whales, Delphinapterus leucas, housed in San Diego Bay. Bulletin of Marine Science. 1997;61(2):377–385. [Google Scholar]

- Ross P, Swart R, Addison R, Loveren H, Vos J, Osterhaus A. Contaminant-induced immunotoxicity in harbour seals: Wildlife at risk? Toxicology. 1996;112(2):157–169. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(96)03396-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PS, Ellisa GM, Ikonomou MG, Barrett-Lennard lG, Addison RF. High PCB concentrations in free-ranging pacific killer whales, Orcinus orca: Effects of age, sex and dietary preference. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2000;40(6):504–515. doi: 10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00233-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samaras WF. New host record for the barnacle Cryptolepas rhachianecti Dall 1872 (Balanomorpha: Coronulidae) Marine Mammal Science. 1989;5(1):84–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1989.tb00216.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman FY, Lipscomb TP. Dermatitis with invasive ciliated protozoa in dolphins that died during the 1987–1988 Atlantic bottlenose dolphin morbilliviral epizootic. Veterinary Pathology. 1999;36:71–174. doi: 10.1354/vp.36-2-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott EM, Mann J, Watson-Capps JJ, Sargeant BL, Connor RC. Aggression in bottlenose dolphins: Evidence for sexual coercion, male-male competition, and female tolerance through analysis of tooth-rake marks and behaviour. Behaviour. 2005;142:21–44. doi: 10.1163/1568539053627712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CF, Wood FG, Young F. Cutaneous lesions on a porpoise with Erysipelas. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association. 1958;133:558–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AW, Skilling DE, Ridgway S. Calicivirus-induced vesicular disease in cetaceans and probable interspecies transmission. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association. 1983;183:1223–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney JC, Ridgway SH. Common diseases of small cetaceans. JAVMA. 1975;167:533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev PI. The overgrowing of whales with diatoms. Zoologikal Zhurnal. 1940;19:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Bressem MF, Waerebeek K. Epidemiology of poxvirus in small cetaceans from the Eastern South Pacific. Marine Mammal Science. 1996;12:371–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1996.tb00590.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bressem MF, Waerebeek K, Reyes JK, Dekegel D, Pastoret PP. Evidence of Poxvirus in dusky dolphin (Lagenorhynchus obscurus) and Burmeister’s porpoise (Phocoena spinipinnis) from coastal Peru. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 1993;29(1):109–113. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-29.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressem MF, Waerebeek K, Raga JA. A review of virus infections of cetaceans and the potential impact of morbilliviruses, poxviruses and papillomaviruses on host population dynamics. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 1999;38(1):53–65. doi: 10.3354/dao038053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressem MF, Gaspar R, Aznar FJ. Epidemiology of tattoo skin disease in bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus from the Sado estuary, Portugal. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2003;56:171–179. doi: 10.3354/dao056171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bressem, M.-F., K. Van Waerebeek, J. Reyes, F. Félix, M. Echegaray, S. Siciliano, A.P. Di Beneditto, L. Flach, F. Viddi, I.C. Avila, J. Bolaños, E. Castineira, D. Montes, E. Crespo, P.A.C. Flores, B. Haase, S.M.F. Mendonça de Souza, M. Laeta, and A.B. Fragoso. 2007. A preliminary overview of skin and skeletal diseases and traumata in small cetaceans from South American waters. Document SC/59/DW4, May 2007. International Whaling Commission, Berlin, Germany, 26 pp.

- Wells RS, Hansen LJ, Baldridge A, Dohl TP, Kelly DL, Defran RH. Northward extension of the range of bottlenose dolphins along the California coast. In: Leatherwood S, Reeves RR, editors. The bottlenose dolphin. San Diego: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B, Thompson PM, Hammond PS. Skin lesions and physical deformities in bottlenose dolphins in the Moray Firth: Population prevalence and age-sex differences. Ambio. 1997;26(4):243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B, Arnold H, Bearzi G, Fortuna CM, Gaspar R, Ingram S, Liret C, Pribanić S, et al. Epidermal diseases in bottlenose dolphins: Impacts of natural and anthropogenic factors. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1999;266:1077–1083. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TM, Cheville NF, Karstad I. Seal pox. Bulletin of Wildlife Disease Association. 1969;5:412–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TM, Cheville NF, Boothe AD. Sealpox: Questionnaire survey. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 1972;8:155–157. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-8.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]