Abstract

Scientific complexity and uncertainty is a key challenge for environmental risk governance and to understand how risks are framed and communicated is of utmost importance. The Baltic Sea ecosystem is stressed and exposed to different risks like eutrophication, overfishing, and hazardous chemicals. Based on an analysis of the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, this study discusses media representations of these risks. The results show that the reporting on the Baltic Sea has been fairly stable since the beginning of the 1990s. Many articles acknowledge several risks, but eutrophication receives the most attention and is also considered the biggest threat. Authorities, experts, organizations, and politicians are the dominating actors, while citizens and industry representatives are more or less invisible. Eutrophication is not framed in terms of uncertainty concerning the risk and consequences, but rather in terms of main causes.

Keywords: Baltic Sea, Complexity, Framing, News media, Risk, Uncertainty

Introduction

Environmental risks transcend traditional boundaries (e.g., nation boarders) and are often said to raise a need for new governing and communication strategies. It also challenges the role of knowledge since risk governance often is about un-known futures. This is not least true for the governance of regional seas like the Baltic Sea. How to cope with complexity and uncertainty in (scientific) knowledge is a key challenge for environmental risk governance and to understand how risks and uncertainties are framed, assessed and communicated is of utmost importance for researchers, policy-makers, or any other actor wishing to take part in or understand processes of risk governance. Media also has a decisive role in defining risks and influencing what issues are to be put on the political agenda (Allan et al. 2000; Hansen 2010).

In Sweden, the environmental risks of the Baltic Sea have been on the agenda (politics, science and the media) for several years and lately much discussed in the context of the Swedish EU presidency during the autumn 2009 and with the political initiative the “Baltic Sea co-operation” that was launched in spring 2009. Despite substantial efforts over several decades by multiple actors on local, national, and international levels, to counteract human induced environmental impacts on the Baltic Sea ecosystem, major disturbances to key ecosystem structures and functions still exist (cf. HELCOM 2010).

So, the Baltic Sea ecosystem is stressed and exposed to many different problems and risks like eutrophication, overfishing, hazardous chemicals, climate change, oil pollution, and introduction of invasive species (cf. HELCOM 2010). But to what extent and in what way are these issues acknowledged in public discourse (here represented by the news media), and have there been any changes over time? Based on an analysis of the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter (1992–2009), this study discusses media representations and framings of risks in relation to the Baltic Sea, a regional sea that has been identified as a special area of protection (PSSA) by the IMO.

The study evolves around two main sets of questions: (1) How is the Baltic Sea and the different environmental risks represented in news media? Which risks receive the most attention and have there been any changes over time? (2) How are environmental risks framed in the news media? What is identified as problems, causes and solutions? Which are the main actors? How do media frame environmental risks in terms of uncertain or certain knowledge? For the framing analysis, the study focuses on eutrophication.

Theoretical Perspectives and State of the Art

It is a starting-point for this article that (news) media matters for risk governance, policy-making and communication in the political sphere. The concepts of the public sphere, mediatization, agenda-setting, and framing will be used as theoretical points of departure in order to present and discuss the relationship between media and society, and how the media influences public discourse and what is defined as risks.

Media and Public Discourse

It has been pointed out that models of the relationship between science and policy-making always should include the idea of the public sphere (Bäckstrand 2003) and a public sphere can be defined as a communicative space for discourse on public matters (cf. Habermas 1989). Today, it is undisputed that media has a decisive role for (risk) governance, policy-making, and communication. News media shape public discourse in terms of participation and representation in that they influence who has access to the arena, who can participate in the discourse, and the subjects that can be discussed (Dahlgren 1995; Cox 2006). The news media also plays a crucial role in defining problems and framing environmental issues as risks.

To further discuss the role of media in contemporary politics (and risk governance), the concept of mediatization has proven useful. Mediatization refers to a situation where media not only has become a central part of the public sphere, but even the main frame of reference in society. Media influences how politics is framed and perceived and set the terms of action for politicians, stakeholders, and other participants in public discourse (Asp and Esaiasson 1996; Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999; Schulz 2004; Strömbäck 2008). “Mediatized politics is politics that has lost its autonomy, has become dependent in its central functions on mass media, and is continuously shaped by interactions with mass media.” (Mazzoleni and Schulz 1999, p. 250). The “media logic” (Altheide and Snow 1979) becomes the logic of public discourse and also limits certain actors with a different kind of logic (for example when scientists are supposed to talk in “sound-bites” in television). In an analysis of the process of mediatization, Strömbäck (2008) concludes that even if mediation of politics is an old phenomenon, politics definitely has become more mediatized.

Schulz (2004) operationalizes mediatization as a process of extension, substitution, amalgamation, and accommodation, where accommodation is the form most similar to the general use of mediatization. In this perspective, mediatization includes other spheres than politics and Schulz claims that the adaption to media logic applies not only to political actors but also to actors in entertainment, sports or other social domains. Schulz also points to the importance of visibility in mediatized politics (see also Thompson 1995). According to Schulz, one of the functions of mediation is the bridging of spatial, cultural and social distances and the way media can offer a forum or a space for communication. Thus, seen in this way the concept of mediatization is closely related to the idea of the (mediatized) public sphere (cf. Dahlgren 1995).

Another concept with relevance for understanding the relationship between media and society and to analyze the role of media in public discourse and political communication is agenda-setting. The concept was coined by McCombs and Shaw (1972) and serves to illustrate the role of the (news) media in political discourse. Their basic idea is that there is a relationship between the amount of attention a certain issue receives in news media, and the extent to which the public considers this issue to be of special importance—what is considered important by the news media is considered important by the public. McCombs (2005) distinguishes between aspects and central themes, and in his perspective, attributes defining a central theme are frames. While agenda-setting theory mainly focuses on which issues are reported, framing is about how issues are reported (Weaver 2007). A frame is the dominant perspective on the object/issue at stake.

The concept of framing has roots in both psychology and sociology and is said to originate from the sociologist Ervin Goffman who discusses framing as an interpretive framework that helps individuals to process information (Goffman 1974; Pan and Kosicki 1993). In the area of policy-making theory and political sociology, the concept of framing is often used for analyzing how actors are actively involved in debating, defining, and setting a particular agenda and furthering its implementation (Rein and Schön 1993). As used in contemporary media studies, framing generally contains two main dimensions; on the one hand, it refers to the way certain aspects in a text are made more salient, and on the other hand it is about how these frames affect the way people perceive and construct reality. According to Robert Entman: to frame is to “select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communication text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, casual interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” for the item described (Entman 1993).

In studies of the role of media and journalism in public discourse, framing is generally used as a way to describe how different issues are represented in the news media. Framing analysis can be used to analyze media texts (e.g., news articles), and how selection, focus of certain words, phrases, or ideas may contribute to shape public perception (Entman 1993; Reis 2008).

Ulrich Beck has in his widely cited work Risk Society from 1986 claimed that risks produced in a late stage of modernity (like, e.g., environmental risks) to a large extent are invisible and only exists through our knowledge about them. This underlines the importance of actors producing and spreading knowledge, like science, and not least, the media. Beck (1992) also claims that we in today’s society have to make decisions on an un-known future without an adequate foundation of knowledge. Knowledge (science) concerning ecological processes and risks are often characterized as especially complex and uncertain (see for example, Renn 2008).

News Media, Risks and Issues of Uncertainty

In Europe and North America, a public discourse on “the environment” seem to have emerged in the end of the 1960s, and, for example, the Time magazine introduced an “Environment” section in 1969. It was not until the 1980s though that an environmental discourse really began to permeate newsrooms in the Western world (Allan et al. 2000). This is also the case for Swedish news media. There are a couple of studies analyzing how the environmental issue has been represented in Swedish news media, and although their focus has been on television, some of the main findings may be relevant for understanding the broader environmental discourse in Sweden.

Djerf-Pierre’s (1996) analysis of environmental news in Swedish television 1961–1994, for example, shows that the discourse has changed over time, both in terms of amount of attention that has been directed toward environmental issues, and when it comes to the characteristics in the reporting. She identifies three epochs and the last period in her study (1991–1994) is defined as the period of popularized environmental reporting. Hermansson’s study (2002) analyzes how environmental politics is covered in the news 1987–1998. A main finding in her analysis is that television news together with formal politics co-created a sense of a “green people’s home” and provided the public with moral guidelines for how to approach the environmental issue as individuals. Hermansson also concludes that television has contributed to an ideological change in society and that there has been an individualization of ecological considerations.

Today environmental issues and risks are considered as hot news items and this in particular goes for environmental crises and natural disasters (Allan et al. 2000). Risks are a common theme in news media, and there has been a lot of research during the years concerning how different risks are represented and framed in journalism and other media genres. Most studies are national and generally focus on one risk or risk area (for overviews, see e.g., Dunwoody and Peters 1992; Allan et al. 2000). There seems to be a high degree of consonance between different countries in how the media portray risks. There are, however, not many studies comparing different risk areas or analyzing environmental risk representation in relation to a certain geographical area (like the Baltic Sea).

Environmental risk issues are often very complex in nature and thus related to a high degree of uncertainty. Confronted by scientific uncertainty, the citizens tend to turn to the media for a greater understanding, but at the same time media and journalists are part of the process of framing science as certain or uncertain knowledge (Allan et al. 2000). As Allan and co-authors also so rightly points out, the process of mediation is in itself characterized by uncertainty, ambiguity and contradiction.

How journalists deal with and construct uncertainty has received some attention from scholars in the areas of, for example, journalism, media, and communication, and science communication studies. In the anthology Communicating Uncertainty from 1999, Friedman et al. address issues like the role of scientific uncertainty and how journalists deal with this challenge. During the last decades, news on science has generally dealt with complex and controversial issues like for example climate change and biotechnology. To communicate uncertain scientific knowledge in this context is considered as a major task for the journalists (Hornmoen 2009). It has also been stated that the media does not necessarily report on the risks identified as most important by scientists. Therefore, there could be a discrepancy between scientists and the media in problem framing. The cultural gap between journalists and scientists seems to be especially evident in communication on risk and uncertainty (Peters 1995).

In order to describe how journalists communicate science to the media audience(s), the concept of popularization is frequently used. For some this equals a critical view where to popularize means to distort scientific knowledge. For others, popularization simply refers to the process of adjusting the message—in this case, the content of the news article—to the audience. The general pattern seems to be that popularization tends to include a reduction of complexities, and thus also a tendency to make scientific knowledge appear more certain than it is (Stocking 1999; Hornmoen 2009). Media tend to simplify and popularize and one common consequence of this is that they often provide simple casual explanations of risks, thus reducing complexity (Boholm 2008).

Previous research has shown that media framing of uncertainty (and certainty) comes in different shapes; journalists sometimes, for example, communicate explicit reservations when referring to expert knowledge; they challenge scientific knowledge with other kinds of knowledge (e.g., common sense), and they quote several different experts and sources with different views. To communicate scientific uncertainty by framing it as an expert controversy is overall a common journalistic strategy (Stocking 1999; Hornmoen, 2009). Since conflict and debate are important news values (cf. Nord and Strömbäck 2005), media tend to frame knowledge as uncertain, complex, and up to debate.

An important part of the uncertainty rhetoric used by scientists as well as journalists is the time perspective and the idea that scientific certainty can be reached in the future. This can be a device for scientists in their argument for the need for more research and knowledge (Hornmoen 2009) and is especially interesting in the context of risks, since the concept of risk in itself also relate to some kind of future.

In the field of environmental and science journalism, the concept of framing is thus closely related to the concepts of uncertainty and risk. What is perceived as an important problem and what is to be defined as a risk, is largely influenced by images and representations in the news media. This study addresses the issue of how news media represent and frame complex risk issues, using the case of environmental risks in relation to a regional sea.

Empirical Data

This article analyzes the extent and in what way, Baltic Sea risk issues are acknowledged in Swedish news media. The daily national newspaper Dagens Nyheter was selected to serve as a case. Dagens Nyheter is one of the most influential newspapers in Sweden both in terms of number of readers and the role it plays for public discourse (other media often use Dagens Nyheter as a source). It is liberal and the largest broadsheet in Sweden (Hadenius et al. 2008). Being situated in Stockholm, it is also in the direct vicinity of the Baltic Sea.

The method used is a combination of a quantitative and a qualitative text analysis. The material consists of news articles collected from the Internet press archive Presstext (www.presstext.se). To find relevant articles on environmental risks (eutrophication, fisheries, biodiversity impacts, chemical pollution, and maritime transportations) and the Baltic Sea, different combinations of keywords were used. For the first set of research questions “How are these environmental risks represented in news media?” and “Which risks receives the most attention and have there been any changes over time?” the search was based on the following keywords (although in Swedish): “Baltic Sea*,” “Baltic Sea* + environment,” “Baltic Sea* + environment*,” “Baltic Sea* + environment* + risk” (Östersjö*, Östersjö + miljö, Östersjö* + miljö*, Östersjö* + miljö* + risk). To get a closer look at how different environmental risks are represented articles from the year of 2009 as the most recent year (for which data for the whole year is available) has been analyzed separately. In order to answer the question if there have been any changes over time, the sample consists of articles from the period 1992–2009. The aim was to cover the period from a few years before Sweden became a member of the European Union and up until today, since it is interesting to see if and how this change in political context with a higher focus on the regional scale affects the discourse on the Baltic Sea. For a comparison, a similar broad analysis was conducted also of newspapers in Gotland (an island situated in the Baltic Sea) and the Swedish west coast.

As for the second research question, on how environmental risks are framed in the news media in terms of what is identified as problems, solutions, main actors, etc., the analysis will focus on the case of eutrophication. This is due to the fact that eutrophication is considered as one of the main risks and also since the case is relatively non-problematic in terms of how well the keywords represent the issue area. Eutrophication is furthermore a case where scientific uncertainty has been acknowledged in public discourse and since one sub-question in this study is to analyze how new media construct uncertain knowledge, this is a suitable case. The sample here consists of articles from the years 1993, 1998, 2003, and 2008. The 5-years interval was selected as a means to get a broad overview. All relevant articles (i.e., those addressing the issue of eutrophication in the Baltic Sea) on the topic resulting from the search with the keywords “Baltic Sea* + eutrophication” have been considered in this analysis.

The main methodological challenge in this study has been to find keywords that really identify the relevant articles. In the case of news on the Baltic Sea in general, and also the Baltic Sea in relation to environmental issues, relevant combinations of keywords were quite easy to find, but the problem arises in the analysis of different risks. Journalists do not necessarily use one or two concepts in the articles to describe a risk or environmental problem and do not always use the concept of risk. While for example “overfishing” has been identified as a risk area, this is a concept rarely used in news media and to find all the articles relevant for this risk topic, it is necessary to go through all articles on the topic of fishing. For the sake of simplicity, this study uses combinations of keywords that actually include a risk-related concept (like “overfishing,” “eutrophication,” etc.) even if this means that some relevant articles will not be included in the sample. This also means that the method for selection of material in some senses in itself can be said to be part of a framing process.

The Baltic Sea in News Media

During the period 1992–2009 Dagens Nyheter published 6,033 articles that in some way concerned the Baltic Sea (Figs. 1, 2). The results show that the Baltic Sea in news media generally is represented as either a political space (e.g., “Baltic Sea cooperation”/“Östersjösamarbetet”) or a geographical place (e.g., weather news “a storm coming in from the Baltic Sea”), and in several cases there are overlaps, like in the many news articles on the Baltic Sea in the context of military safety issues. Especially in 2008, the company Nord Stream’s planned gas pipeline between Russia and Germany got quite a lot of attention and this issue was generally framed as either a military safety issue or an environmental issue (or sometimes both). Thus, the environmental risk discourse overlaps with other discourses.

Fig. 1.

The Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter. Photo: Mats Eriksson

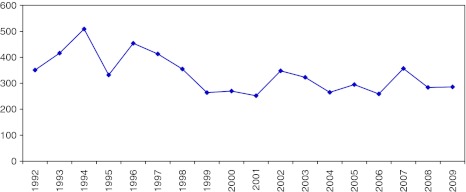

Fig. 2.

Number of news articles dealing with the Baltic Sea in Dagens Nyheter 1992–2009

Another finding is that even if there are variations between different years, the general pattern is that the Baltic Sea was more visible in the news in the 1990s than in the 2000s. One possible explanation for this is that the beginning of the 1990s was characterized by the discussion on a possible Swedish membership in European Union (Sweden had a referendum in 1994 and joined in 1995), and the Baltic Sea area was one of the issues with clear relevance for this regional context. During these years, there were also a number of political initiatives concerning Baltic Sea Environment, like for example the establishment 1992 of the Council of Baltic Sea States (CBSS), and a new (also from 1992) HELCOM convention, as well as the declaration in 1996 on a Baltic 21 initiative (cf. Kjellén 2007).

Dagens Nyheter is a national newspaper but at the same time (being situated in Stockholm) it may be influenced by its closeness to the Baltic Sea, and not surprisingly the Baltic Sea as a news topic is more common in Dagens Nyheter than in for example Göteborgs-Posten (the biggest newspaper on the Swedish west coast). Following the same pattern, the local newspapers (Gotlands Tidningar and Gotlands Allehanda) on the island Gotland, situated in the middle of the Baltic Sea, have the most extensive reporting on the Baltic Sea.

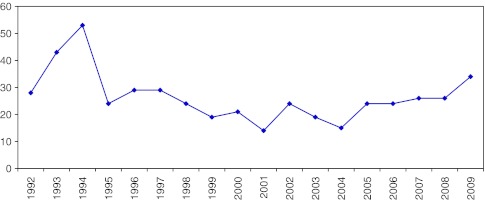

In many articles, the Baltic Sea is presented as an environmental problem area. Generally between 25 and 35% of the news articles in Dagens Nyheter concerning the Baltic Sea address environmental issues in some way, and the results of the analysis show that this reporting (as the reporting on the Baltic Sea in general) has been fairly stable since the beginning of the 1990s (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Number of news articles dealing with the Baltic Sea and Environment in Dagens Nyheter 1992–2009

In the context of theories on mediatization and agenda-setting, it is relevant to ask what these results really mean. It is of course difficult to say if the amount of attention the Baltic Sea and especially the different environmental risks receive in Dagens Nyheter is high or low since there is not a real good comparison available. As a point of reference though, it can be noted that while there in 2009 were 286 articles on the Baltic Sea in any form, there were 443 articles addressing the Swineflue, 2,702 articles on football, and 45 articles with some reference to the North Sea.

As noted above, the Baltic Sea ecosystem is exposed to many different problems and risks like eutrophication, overfishing, hazardous chemicals, climate change, oil pollution, and introduction of invasive species. But to what extent and in what way are these issues acknowledged in the news? Many articles acknowledge several different risks, but if we take a look at the risks separately (in the cases when they are framed as environmental issues), it can be stated that eutrophication is the environmental risk that receives the most media attention (in terms of number of articles). Eutrophication in terms of algal blooming is also one of the most “visible” of the environmental risks, something that could render it a higher news value (cf. Anderson 1997; Fig. 4). So is the possibility for consumer identification (cf. Shoemaker and Reese 1996), another area where eutrophication (or algal blooming) scores high, since it can be related to vacation times, negative health effects, the possibility to swim in the sea, etc. Thus, eutrophication seems like a risk that is relatively easy for the journalists to popularize.

Fig. 4.

Cyanobacterial blooming in Bödabukten north of Öland in July 2005 (Photo: Elinor Andrén)

It is obvious from the media discourse that the different risks and problems are intertwined in complex ways in terms of causes, effects, etc. Overfishing and eutrophication are for example often linked, like in the example below (my translation):

The last cod

/…/The cod in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea is now in trouble./…/The situation for the cod in the Baltic Sea is only partially better than in the North Sea, and here we also must add the serious environmental problems. The thought of a one-sided Swedish stop for cod fishing, thus is not a fuzzy whim from the Green Party, but instead a necessary measure in the eleventh hour. A lot of other things also have to be done: more resources for science, selective and lenient tools, reduced eutrophication of the sea, labeling of fish that gives the consumers a possibility to affect the methods for fishing. (Dagens Nyheter, November 3, 2002, my italics)

Overfishing, marine transportation, and eutrophication are also often related to issues of biological diversity, and then mainly framed as causes for loss of biological diversity.

In order to look more closely at the question of how different environmental risks are portrayed and the amount of attention that is directed toward certain problem areas, the year of 2009 has been analyzed separately. In 2009, there were a total of 286 articles that in any way contained the keyword “the Baltic Sea”. A little over one third of the articles addressed environmental issues; about 10% were about general political issues (like the Baltic Sea cooperation), and almost 10% of the articles reported on issues related to economy and the financial sphere (e.g., the Euro). About 40% of these articles were about issues with no relevance for this study (the categories “other” and “Arctic sea”) and contained news on things like cultural events in the Baltic Sea region, cruising information, accidents (e.g., “Two people injured in fire on ferry,” Dagens Nyheter August 19, 2009), etc.

The articles were analyzed and categorized for their main content in broad themes. This means that if one article, for example, was about eutrophication, fishing, and economy, it was categorized based on the main frame or theme. This was decided with reference to headline and the amount of the article addressing the different risk areas. As an example, we can take an article from February 28, 2009 with the headline “Phosphates will be forbidden in machine detergents” (“Fosfater förbjuds i maskindiskmedel”). This article is about a political decision with the aim to in 2 years time forbid the use of phosphates, and one of the reasons behind this decision is that the discharge of phosphates is said to be “the most important cause for eutrophication”. In this case, the article addresses both the issue of chemical pollution and eutrophication, but since the headline is about chemical pollution and so also the main event (the political decision) in the article, it has been placed in the chemicals-category.

Analyzed in this way, it is overfishing that receives the most attention of the different environmental risks (e.g., “Fishermen at Österlen hope for abolished red listing of cod,” Dagens Nyheter April 29, 2009). This means that while eutrophication is the risk most often mentioned in the Baltic Sea news, it rarely, unlike, e.g., overfishing, is represented as a main theme. It is also interesting to note that marine transportation (e.g., oil shipping) is more or less invisible as an environmental risk issue in 2009, while it in the spring 2010, in the context of the BP oil catastrophe in the Mexican Gulf, has become a major area of interest for news media. This is an example of a phenomenon that in theory of news production and news values is sometimes presented as “threshold-passing” and related to issues of relevance and public discourse. When an event or a certain issue area has passed the news threshold and considered an important part of the agenda, news media work with follow-ups and contextualizing future events in the light of this issue area, thus increasing the amount of attention for that particular issue (cf. Galtung and Ruge 1965).

As for the representation of different risks, it can be concluded that they are closely related and that an issue being identified as a risk area in one article can be framed a cause of another risk in another article. How environmental risks are framed in news media is one of the main questions for this article, and next the case of eutrophication will be used for a deeper analysis on this matter.

Framing Eutrophication

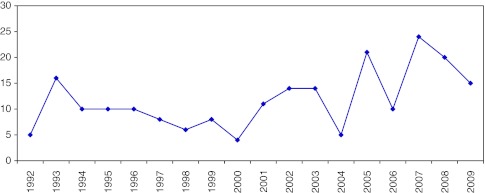

As can be seen in Fig. 5 below, there are many fluctuations in how the issue of eutrophication has been reported in Dagens Nyheter during 1992–2009, but at the same time there is a pattern pointing to an increase during the last 10 years.

Fig. 5.

Number of news articles dealing with eutrophication in Dagens Nyheter 1992–2009

An important part of the framing process concerns which actors that participate in the news. Media audiences are invited to different interpretations and to view the issue area through the eyes of certain actors, thus promoting certain interpretive frames (Hornmoen 2009). The main actors in the mediated discourse on eutrophication are authorities (e.g., The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and The Swedish Board of Agriculture), and different scientific experts (mainly natural scientists). Politicians and representatives from organizations and NGOs like The Swedish Society for Nature Conservation and The Federation of Swedish Farmers are also highly visible actors in the media discourse on eutrophication.

In Hornmoens’ analysis of science journalism (2009), the public and other non-experts are only present in news texts as an implied audience, and the same pattern can be found in this study. The public as citizens’ voices is more or less invisible in news on the Baltic Sea and eutrophication (and in fact in news on all environmental risks in the Baltic Sea). In one case, a fisherman gets a saying and in another article it is a farmer, but apart from that there are no individual citizens in the news on eutrophication. On some occasion the citizens, like in the following quote, are referred to as a collective: “there is evidently a strong opinion…”. It is also worth noting that representatives from the industry and business sector (with the exception of farmers) are just as invisible as the citizens. Based on these results, it can be concluded that the power to define problems and solutions mainly lies in the hands of experts, authorities, and policy-makers. To communicate and in some ways promote the findings and research of a narrow group of sources is seen as a traditional journalistic practice in the quest for constructing certainty (Nelkin 1995; Hornmoen 2009).

Eutrophication is generally framed as a problem and an environmental risk. It is often presented as the most important problem and most dangerous risk for the Baltic Sea. There are, however, also several examples when eutrophication is framed as a cause of other risks, and then mainly loss of biodiversity. In terms of what is framed as problems and solutions for eutrophication, the general pattern is that agriculture and its use of phosphor and nitrogen is presented as the main problem, and political restrictions on agriculture (e.g., discharge taxes) are often presented as the solution. Other causes that are discussed quite frequently are the traffic and the fishing sectors, while issues like forestry and shipping are more or less neglected. In the framing of eutrophication, various obstacles for risk governance are also presented as part of the problem frame. The transboundary character of the risk and the problem of coordinating several different countries and the costs for the agricultural sector in implementing tools for reduction of nitrogen and phosphor, are two of the obstacles most often mentioned. It is also obvious that there is a kind of “us against them” dimension in the Swedish discourse; Poland, Russia, and the Baltic States are identified as the villains and therefore framed as part of the problem. The European Union on the other hand is presented as a possible solution to the problem of cooperation and coordination.

Especially in the end of the period, there is a tendency to frame eutrophication as part of a wider context and to discuss the Baltic Sea as a problem area in terms of environmental risks. There is, however, very few references to an ecosystem-based approach—an approach that has been adopted by for example HELCOM and is a part of the Baltic Sea Action Plan (BSAP) (HELCOM 2007). In the news on eutrophication in Dagens Nyheter, there are only a couple of references to HELCOM and the BSAP. In the cases when readers get contextualization and a presentation of a more complex picture, it is often not in regular news articles, but instead in editorials and news in the science section. It is, for example, only in a couple of editorials (and not in any news articles) that the concept “ecosystem” is actually mentioned. This means that only a small part (middle-aged, highly educated) of the readers actually take part of that fuller and more complex picture of the eutrophication problem.

In the case of eutrophication, there seems to be no uncertainty concerning the risk and consequences but rather in terms of main causes (and therefore solutions). Discharges of phosphor and nitrogen are the problem, but there is no certain knowledge concerning which one of these that are the biggest threat and what are the most effective measures and tools. The uncertainty concerning nitrogen and phosphor is sometimes framed as an explicit uncertainty and lack of knowledge, here expressed by Rune Hallgren from LRF (The Federation of Swedish Farmers): “Is it phosphor or nitrogen we should focus on? If we are forced to do things we at least need to know that those are the right things” (Dagens Nyheter August 7, 2008). In other cases, uncertainty is an implicit feature in the news and is expressed in the way that one article focus on one aspect, another article (sometimes next to it, sometimes in another part of the newspaper or in another day) on another. In some cases, new findings are presented as new facts without contextualization. There are only few examples of journalists framing issues as uncertain by presenting opposing views, and in the cases there are, it is not so much scientific controversies, but rather differences of opinions between different sources like The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and The Swedish Board of Agriculture, where the former more strongly advocates measures directed toward the agricultural sector.

It can sometimes be hard to distinguish between uncertainty and dissonance, and one example is the uncertainty concerning the role of the agricultural sector. This is by far the most problematic sector according to the news reports (“The most prominent cause behind the dying seabeds is discharges of phosphor and nitrogen from the agricultural fertilization.” Dagens Nyheter 24 June, 2008), but there are also voices raised against this picture. As mentioned above, there are uncertainties expressed in relation to different solutions, and for example how effective political restrictions and legislation can be. An editorial discussing among other things fish stocks and eutrophication in relation to dying sea beds, expresses the uncertainty of knowledge in the following manner: “How close in time is hard to say. Not least since humans actually do not know that much about the sea.” (Dagens Nyheter August 16, 2008). This is a direct claim of uncertainty and also an example of how uncertainty is framed in relation to time.

Compared to what has been shown in previous research (Stocking 1999; Hornmoen 2009), the tools used by journalists to frame an issue as uncertain, mainly seem to be to quote several different experts and sources with different views. The general pattern though is that eutrophication as an environmental risk in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter is not framed in terms of uncertain scientific knowledge, but rather as a certain threat that needs to be taken care of immediately, and the uncertainty instead is about the measures and what are the best, most effective and cheapest solutions. News articles on eutrophication also tend to reduce complexity, and in that sense perhaps present issues as less uncertain than they are (although this is less true for editorials and articles in the science section).

Discussion

Case Study Approach

The results show that the Baltic Sea in news media generally is represented as a political space or a geographical place, and that the Baltic Sea received more attention in the news media in the 1990s than in the 2000s. News on environmental risks and the Baltic Sea obviously, when it comes to news values, is guided by the same principles as news in general. Issues and events regarding politics and economy, sensations like crisis, accidents, etc., are generally considered highly interesting, and the main actors in the news are elite sources related to different power spheres in society.

The reporting on the Baltic Sea in relation to environmental issues has been fairly stable since the beginning of the 1990s. It is also obvious from the media discourse that the different risks and problems are intertwined in complex ways in terms of causes, effects, etc. Many articles acknowledge several different risks, but eutrophication is the environmental risk that receives the most media attention and is also considered to be the biggest threat. Some of the main actors in the mediated discourse on Baltic Sea risks are authorities, scientific experts, organizations, and politicians. The public as citizens’ voices is more or less invisible. In the analysis of complexity and uncertainty, the conclusion for the case of eutrophication is that there seems to be no uncertainty concerning the risk and consequences but rather in terms of main causes (and therefore solutions). Discharges of phosphor and nitrogen are the problem, but there is no certain knowledge concerning which one of these that are the biggest threat.

Before moving on to possible implications and consequences of these results, it seems fair to address the question of what the results really represent. Does the case Dagens Nyheter represent other news media than itself? It is certainly difficult to say if a case study like this of national (Swedish) media reporting on regional environmental risk issues also can say something about media representations in other countries. For one thing there is a lack of previous research concerning how environmental risks in relation to the Baltic Sea are portrayed in the news media to compare with. One reason for this is possibly that it is also a relatively new political area, and that the Baltic Sea as a regional sea is not part of a particular nation, but rather part of several nations. There are, however, no real regional media operating in the same area (like there are no news media at a European level). The studies that can be found are generally case studies on specific risks in certain countries, like the study by Lyytimäki (2007) on eutrophication in Finish press with the focus on temporal variations, driving forces, etc. Based on the results of his study, it can be stated that long-term driving forces and pressures causing eutrophication tend to receive little attention and that eutrophication in the news media often is connected with algal blooming. These conclusions can also be confirmed by this study.

News on environmental risks in the Baltic Sea in Dagens Nyheter is mainly focusing on the Swedish context in the framing of causes, consequences and solutions to risks like eutrophication, but there is also a transnational or regional discourse (mainly related to EU) focusing on for example cooperation, the Baltic Sea Action Plan and the role of different countries. The main impression though, is still the nationalistic character of the mainstream mediated public sphere.

The result of this study then is probably best seen as an example of how environmental risk issues concerning the Baltic Sea area are framed in a national media context in one of the Baltic Sea countries. It is probably also fair to make the assumption that this media image is more similar to other Western European Baltic Sea countries than its Eastern counterparts. The same conclusion is made in a study of the chemical news discourse in Swedish and Polish press 2007/2008 (Egan Sjölander et al. 2010). As discussed above, the newspaper Dagens Nyheter is a leading media in Sweden and could be assumed to represent a mainstream national media discourse. In any case, it is interesting to analyze how one of the agenda-setting and most widely spread news media represent these issues. For the framing analysis, the case of eutrophication was chosen and this obviously affects the results. Other risks are framed in other ways in terms of main actors, degree, and form of complexity and uncertainty, etc., and the analysis of eutrophication must, therefore, be seen as a case of how media work to frame a risk issue.

Consequences of Media Discourse

A starting-point for this article was that (news) media matters for risk governance, policy-making, and communication in the political sphere. Framing of environmental risks influences what is put on the agenda and becomes part of public discourse and much of the public debate take place in the mediated arena. With the assumption that media can influence what people think about and how they think about things in the public sphere (agenda-setting and framing), a general conclusion based on this study is that the media discourse has put the Baltic Sea and the environmental risks related to it, on the public agenda, and that the main focus is on eutrophication, algal blooming, and overfishing. The different risks are mainly treated separately, and the situation for the Baltic Sea environment, therefore, appear as less complex than it is; something that does not go well in hand with the Ecosystem Approach to Management perspective. Another conclusion is that solutions and recommendations are framed as macro issues, while the role of the individual citizen is not addressed.

Although working with the assumption that media influences public discourse and public opinion, it must be noted that there really is no clear line from media content to the way media affects us. As expressed by Nilsson et al. (2000) media content does not equal media effects. People make sense of media texts through drawing upon their own local knowledge, everyday experiences and cultural values. There are significant individual differences in how people respond to the media agenda and those differences are for example explained by the need for orientation. The need for orientation, which is about how individuals want and seek information about society, is dependent on relevance and uncertainty. “Low relevance defines a low need for orientation; high relevance and low uncertainty, a moderate need for orientation; and high relevance and uncertainty, a high need for orientation” (McCombs 2005, p. 547). According to McCombs, a rising level of need for orientation goes together with an increase in media use on public affairs and also with an acceptance of the agenda in the news media.

Against this backdrop, a main argument in this discussion is that conclusions on the effects and consequences of media frames and representations must be problematized and contextualized. For example, we must take into consideration the fact that different media have different functions and that there are several forms of media “effects” (e.g., long and short term effects; effects on behavior or opinion; effects on society or individuals, etc.).

To put it a bit simplistic, two of the main roles for the media in contemporary society are from a normative perspective to inform and to function as an arena for communication and participation (Dahlgren 1995; Cox 2006). What is put forward by advocates for a deliberative democracy and an important part of the idea of “good governance” is that decisions should be preceded by discussions in the public arena, and that these discussions should involve those affected by the decisions (CEC 2001). The news media can be said to be both an actor in the public discourse as well as an arena within which it takes place. In this context, it is worth noting that, as is often the case in environmental news reporting, the public as an individual citizen is more or less invisible. Environmental risks are framed as problems on a societal level and a problem to be solved by public policies and decision-making procedures generally do not seem to include the citizens, at least not in the studied case.

However, this is the situation concerning the mainstream traditional news media. Digital technology and especially Internet have reshaped the conditions for communication. Online public spheres are often said to be more inclusive and with the capacity to create new spaces for deliberation. Internet and the new media are also presented as possible driving forces in the transnationalization of the public sphere (Sparks 2001; Bohman 2004). Since the area of risk governance to a large extent is characterized by a need for transnational discussions and decisions and an increased involvement of citizens, the issue of how environmental risks (e.g., in relation to the Baltic Sea area) are framed and discussed in online media is an important area for further research.

Acknowledgments

Financial support has been received from the Joint Baltic Sea Research Program BONUS+, and the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies. Great thanks also go to two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Biography

Anna Maria Jönsson is an associate professor in media and communication studies at the Departement of Culture and Communication, Södertörn University in Sweden. Her research interests include journalism and the public sphere, science and environmental communication.

References

- Allan, S., B. Adam, and C. Carter. 2000. Introduction: The media politics of environmental risks. In Environmental risks and the media. London: UCL.

- Altheide DL, Snow RT. Media logic. Beverly Hills: SAGE Publications; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A. Media culture and the environment. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Asp K, Esaiasson P. The modernization of Swedish campaigns: Individualization, professionalization, and medialization. In: Swanson DL, Mancini P, editors. Politics, media, and modern democracy: an international study of innovations in electoral campaigning and their consequences. Westport: Praeger; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckstrand K. Civic science for sustainability: Reframing the role of experts, policy-makers and citizens in environmental governance. Global Environmental Politics. 2003;3:24–41. doi: 10.1162/152638003322757916. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck U. Risk society. London: SAGE; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman J. Expanding dialogue: The Internet, the public sphere and prospects for transnational democracy. The Sociological Review. 2004;52:131–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00477.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boholm, M. 2008. Komplexa risker i Göta älvdalen. En innehållsanalys av medierapportering, 1994–2007. Cefos, Rapport 2008:1. Göteborgs Universitet (in Swedish).

- CEC (Commission of the European Communities). 2001. European Governance. A White Paper, 25.7.2001 COM (2001) 428 final, Brussels.

- Cox R. Environmental communication and the public sphere. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren P. Television and the public sphere. London: SAGE Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Djerf-Pierre, M. 1996. Gröna nyheter. Miljöjournalistiken i televisionens nyhetssändningar 1961–1994. Institutionen för journalistik och masskommunikation, Göteborgs Universitet (in Swedish, English summary).

- Dunwoody S, Peters HP. Mass media coverage of technological and environmental risks: A survey of research in the United States and Germany. Public Understanding of Science. 1992;1:199–230. doi: 10.1088/0963-6625/1/2/004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egan Sjölander, A., K. Wolanik-Boström, and K. Ögren. 2010. Framing Chemicals in Sweden and Poland. Journalists’ narratives and media texts. In Regulating Chemical Risks: European and Global Challenges, eds. J. Eriksson, M. Gilek, and C. Rudén. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication. 1993;43(4):51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SM, Dunwoody S, Rogers CL. Communicating uncertainty. Media Coverage of new and controversial science. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung J, Ruge MH. The structure of foreign news. Journal of Peace research. 1965;2:64–91. doi: 10.1177/002234336500200104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper & Row; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas J. The structural transformation of the public sphere. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hadenius, S., L. Weibull, and I. Wadbring. 2008. Massmedier. Press, radio och tv i den digitala tidsåldern. Stockholm: Ekerlids förslag (in Swedish).

- Hansen A. Environment, media and communication. London: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- HELCOM. 2007. HELCOM Baltic Sea Action Plan. HELCOM Ministarial Meeting, Krakow, Poland, 15 November 2007.

- HELCOM. 2010. Ecosystem Health of the Baltic Sea. HELCOM initial holistic assessment, BSEP No. 122.

- Hermansson, C. 2002. Det återvunna folkhemmet. TV-journalistik och Miljöpolitik i Sverige 1987–1998. Linköping Studies in Arts and Science 252 (in Swedish, English summary).

- Hornmoen, H. 2009. What researchers now can tell us—representing scientific uncertainty in journalism. Observatorio 3(4).

- Kjellén, B. 2007. Svensk politik för miljö och hållbar utveckling i ett internationellt perspektiv. En förhandlare reflekterar. Rapport till expertgruppen för miljöstudier 2007:3. Regeringskansliet, Finansdepartementet (in Swedish).

- Lyytimäki J. Temporalities and environmental reporting: Press news on eutrophication in Finland. Environmental Sciences. 2007;4(1):41–51. doi: 10.1080/15693430701295866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni G, Schulz W. Mediatization of politics: A challenge for democracy? Political Communication. 1999;16(3):247–261. doi: 10.1080/105846099198613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs M. A look at agenda-setting: Past, present and future. Journalism Studies. 2005;6(4):543–557. doi: 10.1080/14616700500250438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs M, Shaw D. The agenda setting function of the mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1972;36:176–187. doi: 10.1086/267990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelkin D. Selling science. How the press covers science and technology. New York: Freeman and Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, Å., J.B. Reitan, A. Tönnessen, and R. Waldahl. 2000. Reporting radiation and other risk issues in Norwegian and Swedish Newspapers. Nordicom-Review no 1/2000, NORDICOM, Göteborgs Universitet.

- Nord, L., and J. Strömbäck. 2005. Hot på agendan. En analys av nyhetsförmedlingen om risker och kriser. KBM:S Temaserie 2005:7 (in Swedish).

- Pan Z, Kosicki GM. Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication. 1993;10(1):55–75. doi: 10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters HP. The interaction of journalists and scientific experts: co-operation and conflict between two professional cultures. Media, Culture & Society. 1995;17:31–48. doi: 10.1177/016344395017001003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rein M, Schön DA. Reframing policy discourse. In: Fischer F, Forester J, editors. The argumentative turn in policy analysis, planning. London: Duke University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Reis R. How Brazilian and North American Newspapers frame the stem cell research debate. Science Communication. 2008;29:316–334. doi: 10.1177/1075547007312394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renn O. Risk governance coping with uncertainty in a complex world. London: Earthscan; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz W. Reconstructing mediatization as an analytical concept. European Journal of Communication. 2004;19(1):87–101. doi: 10.1177/0267323104040696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker P, Reese S. Mediating the message theories of influences on mass media content. White Plains: Longman; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks C. The Internet and the global public sphere. In: Bennett LW, Entman RM, editors. Mediated politics. Communication in the Future of democracy. Cambridge: University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stocking HS. How journalists deal with scientific uncertainty. In: Friedman SM, Dunwoody S, Rogers CL, editors. Communicating uncertainty. Media coverage of new, controversial science. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck J. Four phases of mediatization: An analysis of the mediatization of politics. The International Journal of Press/Politics. 2008;13(3):228–246. doi: 10.1177/1940161208319097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver DH. Thoughts on agenda setting, framing, and priming. Journal of Communication. 2007;57:142–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00333.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]