Abstract

Global trends of increasing rural–urban migration and population urbanization could provide opportunities for nature conservation, particularly in regions where deforestation is driven by subsistence agriculture. We analyzed the role of rural population as a driver of deforestation and its contribution to urban population growth from 1970 to the present in the Atlantic Forest of Argentina, a global conservation priority. We created future land-use-cover scenarios based on human demographic parameters and the relationship between rural population and land-cover change between 1970 and 2006. In 2006, native forest covered 50% of the province, but by 2030 all scenarios predicted a decrease that ranged from 18 to 39% forest cover. Between 1970 and 2001, rural migrants represented 20% of urban population growth and are expected to represent less than 10% by 2030. This modeling approach shows how rural–urban migration and land-use planning can favor nature conservation with little impact on urban areas.

Keywords: Globalization, Human demography, Deforestation, Landscape planning, Subtropical Argentina, STELLA

Introduction

Land-use dynamics and deforestation result from complex socio-economic processes (Walker 1987; Mather and Needle 1998; Angelsen and Kaimowitz 1999; Grau and Aide 2008). In many regions, recent deforestation is mostly driven by the expansion of modern agriculture associated with an increasing global population and consumption. However, traditional shifting agriculture, which includes subsistence agriculture or production for local markets, continues to be an important driver of deforestation in many tropical areas (Grau and Aide 2008; Achard et al. 2002); and it is closely linked with local rural population dynamics (Geist and Lambin 2002).

Rural population dynamics can result in two contrasting scenarios of land-use change, deforestation or “Forest Transition”. Forest Transition theory predicts that as societies undergo economic development, industrialization, and urbanization, forest recover will increase (Mather and Needle 1998). Case studies in the Amazon (Laurance et al. 2002), Central American lowlands (Hecht 1993), and South American dry forests (Jepson 2005) show that tropical deforestation has frequently been associated with increasing rural population due to immigration and high natality rate. In contrast, in other tropical and subtropical regions, the trend towards increasing urbanization can favor land abandonment and forest recovery (e.g., Grau et al. 2003; Klooster 2003). Since rural–urban migration and population urbanization has become the dominant global trend (UNFPA 2007), some authors have argued that this will facilitate ecosystem recovery (Aide and Grau 2004) and reduce net deforestation rates and biodiversity losses (Wright and Muller-Landau 2006). However, others authors argue that the increasing demand for resources by the urban population will lead to more deforestation even if the rural population declines (Brook et al. 2006; Sloan 2007). Additionally, migration into cities could promote urban environmental and social problems by increasing the demand for energy, food, and services (Meyerson et al. 2007).

This debate has strong implications for the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services provided by natural ecosystems. The lack of agreement partly arises from the scarcity of detailed local studies that specifically investigate the relationship between rural population dynamics, deforestation, and land-use change in the context of changing demographic and socioeconomic trends associated with globalization. In particular, there is a need to quantify the relative contribution of rural–urban migration to changes in forest cover, and to conduct integrated assessments of the effects of rural demography on both rural and urban environments.

In this study, we explored the relationships among rural population dynamics, environmental policies, and land-use change using a dynamic modeling approach in the Upper Parana Atlantic Forest ecoregion in northeastern Argentina in the province of Misiones. The study region is of interest because it has a high conservation value and it is experiencing rapid land-use and socioeconomic change (e.g., increase in tourism and commodity exports). The model was parameterized to describe the changes in the land-use patterns associated with rural–urban migration between 1970 and 2001. With this model, we created future scenarios to the year 2030 by varying demographic parameters and landscape planning. In addition to assessing the implication of rural emigration for land-cover change, we used the model to quantify the contribution of rural–urban migration to urban population growth.

Study Area

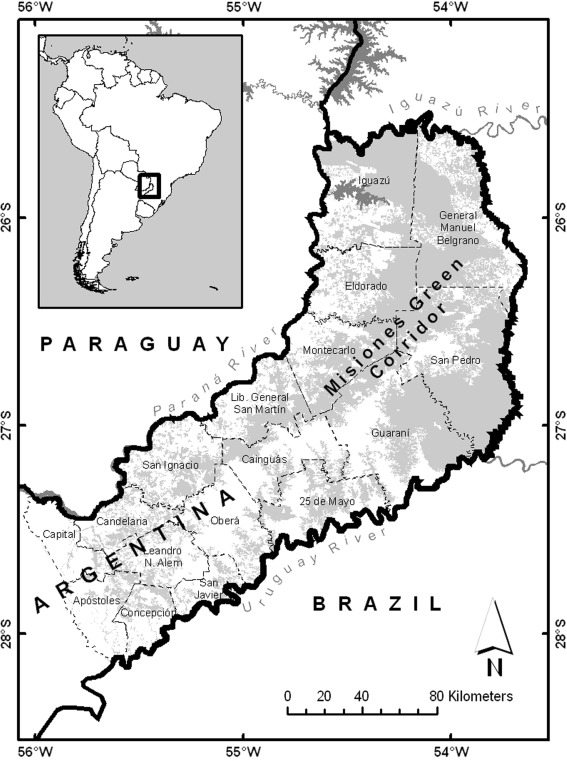

This study was conducted in the province of Misiones (29,801 km2) in northeast Argentina (Fig. 1). Misiones is divided into 17 departments, the smallest administrative unit for which reliable demographic data are available. Misiones includes the largest remaining area of continuous Atlantic Forest (~10,000 km2). The Atlantic Forest extends into southern Brazil and eastern Paraguay, but in contrast to Argentina, in these countries it is highly fragmented and occupies less than 6% of the original cover mainly due to conversion to agricultural (Galindo-Leal and Gusmão-Câmara 2003). The Atlantic Forest ecoregion is of global importance for conservation due to its high level of biodiversity and endemism. It was classified as “endangered” based on the levels of habitat loss and protection (Hoekstra et al. 2005), it is one of Conservation International’s Hotspots (Myers et al. 2000; Mittermeier et al. 2004), and one of WWF’s “Global 200” conservation priority ecoregions (Olson and Dinerstein 2002).

Fig. 1.

The study area showing the location of Misiones in South America (inset), and the location of the departments within Misiones

Land-Use and Cover Trends

In addition to native forests, Misiones includes four major land-use classes: modern agriculture, forest plantations, mixed use (i.e., subsistence agriculture), and pastures (Izquierdo et al. 2008). Modern agriculture is mainly dominated by perennial crops, particularly yerba mate and tea (Manzi 2000). Argentina is the main producer and consumer of yerba mate, the most important perennial crop in Misiones. Forest plantations are mainly Pinus and Eucalyptus. Between 1973 and 2006, the area in forest plantations increased from 1 to 11% of the province, replacing native forests, agriculture, and pastures (Izquierdo et al. 2008), partly due to government subsidies (Placci and Di Bitetti 2006). Cattle grazing occurs in native grasslands in the southwestern departments and in pastures created in previously forested areas in the central and northern departments (Izquierdo et al. 2008). In addition, cattle grazing occurs within forests, which involves the clearing of the understory to enhance grass productivity and forage access for livestock. Mixed use (i.e., subsistence agriculture mainly dominated by annual crops like tobacco and maize) is carried out by small producers in small agriculture units. It is an economically unstable activity because these producers do not have easy access to markets, credit, or other economic incentives that are available to larger producers, and consequently small producers often sell their properties to large producers or companies, which then use these lands for intensive agriculture or plantations (Laclau 1994; Colcombet and Noseda 2000). Economic development in Misiones has lagged behind most of the other provinces of Argentina (Gasparri and Grau 2006), and this has resulted in a relatively large proportion of the area still covered by forests. Misiones is the Argentine province with the highest proportion of protected area (5,100 km2; ~17% of the province). Presently, the government is in the process of developing a landscape planning program that will likely exclude extractive activities from an additional ~10,000 km2 of forest. This legislation (Proyecto de Ley de Ordenamiento Territorial de la Provincia de Misiones), which is presently under discussion in the province Senate, categorizes the territory in three classes: category I—areas where no productive activities are permitted; category II—areas where sustainable activities are allowed if no forest cover is lost; and category III—areas of low conservation value, which can be converted to other uses. Even though the project is still under discussion, in the preliminary maps ~15% of current forest cover is classified as category I, ~60% in category II, and ~25% in category III.

The two largest patches of native forest are included in one area known as the “Corredor Verde” (Green Corridor), mainly located in the six departments in northern Misiones (Fig. 1). Iguazú National Park (~670 km2) and Urugua-I Provincial Park (~880 km2) in the departments of Iguazu and Belgrano make up the northern patch, which is adjacent to the Iguaçu National Park in Brazil (with an additional ~1,850 km2 of forest). The southernmost patch, Yaboti Biosphere Reserve (~2,300 km2), is located in the department of San Pedro. Due to the high conservation value of these patches, there are ongoing initiatives to maintain biological corridors between them (Giraudo et al. 2003). The main productive activities in the six northern departments are forest plantations in Iguazu and Eldorado, and modern and subsistence agriculture in Belgrano, San Pedro, and Guarani. Montecarlo is the principal cattle zone of Misiones and it also has large forest plantations.

Demography and its Relationship with Land-Use Change

The population of Misiones increased by >500,000 people between 1971 and 2001 and virtually all growth was in the urban areas (Table 1). Between 1971 and 1991 the rural population increased by 8,426 people (3%), but between 1991 and 2001 it decreased by 10,024 people (3.4%) (Table 1). Although urbanization has accelerated since 1970, Misiones continues to have a large rural population in comparison to the rest of Argentina (Table 1), and the rural population has continued to increase in four of the six northern departments. The department of Iguazú is the main exception to this pattern: Puerto Iguazu, the department capital, is the city with highest growth rate in the province (10.25%) in the last decade (INDEC 1947, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1991, 2001) as a consequence of being the center of tourism for the neighboring Iguazu Falls, and a major commercial center associated with international shopping in Brazil and Paraguay. Urban growth in Iguazu accelerated rapidly following the Argentina economic crisis (2001–2002) after which the monetary exchange rate has favored international tourism.

Table 1.

Demographic variables for Argentina, Misiones, and the six northern departments in 2001 (last population census); and rural population change between 1970 and 2001

| Argentina | Misiones | Six north departments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population change (1970–2001) | |||

| Total | 12,895,699 | 522,502 | 185,272 |

| Urban | 14,136,519 | 574,076 | 154,801 |

| Rural | −1,240,820 | 8,426 | 30,471 |

| % Rural population 2001 | 10.5 | 29.5 | 37.5 |

| Growth ratea (×1,000) | 10.1 | 19.4 | 20.4 |

| Natality ratea (×1,000) | 17.5 | 22.7 | 29.2c (21.3–32.3) |

| Mortality ratea (×1,000) | 7.8 | 5.6 | 3.4c (2.7–5.5) |

| Rural migratory balancea (×1,000) | −23.2b (21.3/−72.9) | −24c (3.75/−73.14) | −13.24c (1.93/73.14) |

aIndividuals per 1,000 inhabitants/year

bProvincial median values (range quartiles)

cDepartmental median values (range quartiles)

The proportion of the rural population of Misiones is much larger than in the rest of the country. Misiones also lags behinds the Argentina average in terms of demographic transition, which is reflected by a higher natality rate in comparison to the national average (Table 1). However, contrary to the predictions of demographic transition theory, the mortality rate of Misiones was lower than the national average (Table 1). Both rates vary greatly among the departments of Misiones with extreme cases such as San Pedro with a high average natality rate of 36.5‰ and a low average mortality rate of 3.4‰.

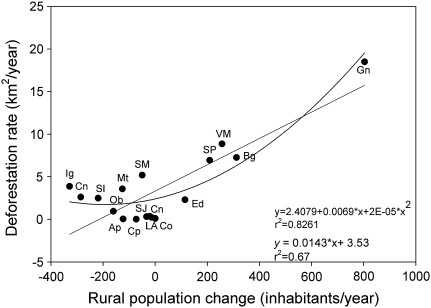

Rural Population and Deforestation

We analyzed the relationship between rural population change and deforestation rate between 1970 and 2006 at departmental scale by using both linear and polynomial regressions. Rural population change was based on the National Population Censuses of 1970, 1980, 1991, and 2001 (INDEC 1970, 1980, 1991, 2001) and the deforestation rates were calculated based on classified images of Landsat from 1973 and 2006 (Izquierdo et al. 2008). Between 1970 and 2001 there was a strong positive relationship between the annual change in rural population and the deforestation rate for the 17 departments (r2 = 0.67/r2 = 0.82; p < 0.005, linear and polynomial regression, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Relation between annual change in rural population and annual deforestation rate from forest to mixed in the 17 departments (Ap Apostoles, Cn Candelaria, Cp Capital, Co Concepcion, El Eldorado, Bg Belgrano, Gn Guarani, Ig Iguazu, LA L. N. Alem, SM San Martin, Mt Montecarlo, Ob Obera, SI San Ignacio, SJ San Javier, SP San Pedro, VM Veinticinco de Mayo)

Model Design and Parameterization

Model Structure

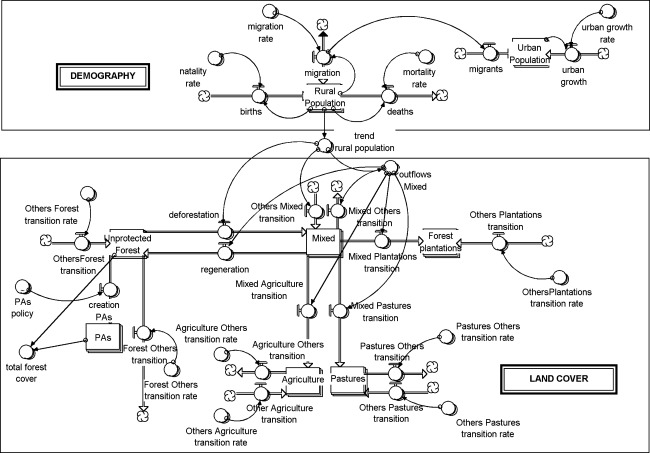

We developed a model (Fig. 3) based on the strong correlation between deforestation and rural population (Fig. 2) using the STELLA graphic programming system (High Performance Systems, Inc.) version 8.03-Research. The model is built as an “Array” with one dimension of 17 elements (i.e., departments) for which the model is replicated, but independently parameterized. The model computes rural population dynamics and land-cover class transitions at the departmental level. The model runs from 1970 (first date of population and land-cover data) to 2030, with time steps and temporal resolution of 1 year. Default options of STELLA are used in the different procedures unless otherwise indicated. The model is divided into two components: Demography and Land cover.

Fig. 3.

Diagram of the array model in STELLA graphic design. Each layer represents a department. Squares represent ‘stocks’ of population or area of different land-cover types. Fluxes of people or land-cover types are represented by thick arrows with a circle in the center of the arrow. Circles are auxiliary variables (‘converters’). Thin arrows represent information flows

The Demography component represents changes in rural population. Rural Population is represented as a reservoir with an inflow given by births; an outflow given by deaths; and a biflow given by migration. Births are the product of the Rural Population multiplied by the natality rate; deaths, the product of Rural Population and mortality rate; and migration is defined by the Rural Population multiplied by the migration rate. Since there are no specific data on migration, migration rate was calculated as the residual difference given (natality − mortality) + migratory balance = population growth from the data on known natality, mortality, and growth rates between 1970 and 2001. The variable trend of rural population is the annual change of rural inhabitants. Urban population is represented as a “stock” with an inflow given by urban growth (which represents the endogenous changes due to natality and mortality) and another inflow given by the net rural–urban migration.

The Land cover component represents the changes in area of the six main “stocks” representing the land-use classes: Mixed (subsistence peasant agriculture), Agriculture (market-oriented), Plantations, Pastures, Unprotected Forest, and Protected Areas (PAs). The “Mixed” stock is a reservoir with two inflows and five outflows. The inflows come from UnprotectedForest (representing the deforestation for subsistence agriculture); and from Others, representing the transition from any cover not represented as a stock (i.e., urban, bare soil, natural grasslands, water, unclassified). The model assumes that there are no transitions to Mixed coming from Plantations or Protected Areas because these covers are rarely converted to other uses. The outflows from Mixed represent transitions to UnprotectedForest, Forest Plantations, Agriculture, Pastures, and Others. The UnprotectedForest is a “stock” of native non-protected forest that is “available” for deforestation; and includes two inflows (from Mixed and from “Others”) and two outflows: “deforestation” to Mixed, and the creation of protected areas. The stocks of Agriculture, Forest Plantations, and Pastures have inflows from Mixed and Others; while Agriculture and Pastures have outflows to Others. The Protected Areas “stock” receives an inflow from UnprotectedForests determined by policies that legislate the creation of protected areas (policy PAs). This relation is represented as a graphical function for each department, which includes the transition of areas from Unprotected Forest to PAs through time. The model assumes that there are no outflows from Forest Plantations and PAs.

All inflows and outflows are regulated by “converters”, control variables that represent the transition rates between different stocks. The variable total forest cover is the sum of km2 in the stocks Forest and PAs. The inflows and outflows to and from Mixed are determined by mathematical functions: the deforestation flow is the best fit relation between the change in rural population (trends of the rural population) and the deforestation rate, while the outflows from Mixed are determined by the relation between the change in rural population and the reduction in Mixed.

Model Parameterization and Calibration

The initial values of Rural Population and Urban Population were obtained from the National Population Census 1970 (32). The natality and mortality rates from 1970 to 2001 were obtained from data published by the Secretary of Statistic of the province of Misiones. The annual growth rates of the rural and urban population were calculated based on data from the National Population Censuses of 1970, 1980, 1991, and 2001 (INDEC 1970, 1980, 1991, 2001). The migration rate was calculated from the natality and mortality rates and rural population. We calculated the annual average growth rate (r) from the census estimates of each department’s rural population as: r = [(t√Pt/Po) − 1] * 1,000, when Po = initial population; Pt = population in t; and t = time. Then we calculated migratory balance (mb) given r = b−d±mb; where r is the growth rate, b is natality rate, d is mortality rate, and mb is migratory balance. Population data are expressed in number of inhabitants and rates are annual.

All the initial values of land cover were calculated for each department from a supervised classification of Landsat MSS satellite images from 1973 (Izquierdo et al. 2008). The rates of transition between the different land-cover categories were calculated from the changes in area between covers from a temporal series of classified mosaics from 1973 to 2006 (Izquierdo et al. 2008). The flow of deforestation was defined by the relation between the changes in rural population (y) and the rate of deforestation from Forest to Mixed (x) (y = 2E−05x2 + 0.0069x + 2.4079; r2 = 0.8262). The cover of PAs includes all the areas with some category of protection, but excludes areas within the Urugua-I Lake Protected Landscape that are covered by an artificial lake or that legally allow some land use other than conservation. All measures of area in the model are in square kilometers (km2) and rates are km2/year.

To assess the accuracy of the parameterization of the model, we ran the model between 1970 and 2006 and compared the predicted areas of the different covers for 2006 with data from the classified mosaics of Landsat images from 2006. The regressions between the classification and the model showed that the dynamic of land-use change is well represented by the model. The regressions for Forest (y = 1.02x + 58.78, r2 = 0.98), Forest plantations (y = 1.046x − 40.19, r2 = 0.83), Pastures (y = 1.11x + 10.17, r2 = 0.95) and Agriculture (y = 0.76x + 52.77, r2 = 0.79) showed that there was a high correspondence between the model and the dynamics calculated from the classified images between 1973 and 2006 (Izquierdo et al. 2008). The regression between the predicted cover of Mixed Use and cover of “Mixed” from the classification was the lowest (y = 0.68x + 52.98, r2 = 0.387), suggesting that there is high variation in the relationship between rural population and deforestation among departments. Nevertheless, we used the same function for all the departments because rural population continues to be a good predictor of deforestation at the provincial level (Fig. 2).

Model Experiments and Scenarios

To quantitatively explore the relative importance of the different variables for the changes in land-use patterns we created different future scenarios for the period 2002–2030 (Table 2). As a reference scenario, we assumed that all the recent past trends would continue. For this in 1.1 reference scenario, we ran the model without modifications (i.e., showing the effects of current trends) until 2030, with one exception: we changed the migration rate of Candelaria and San Pedro to the provincial average because the population growth rates of the last decade of these departments were unusually high (26 and 29‰, respectively) and thus unlikely to continue in the future.

Table 2.

Descriptions of the future scenarios (2006–2030), which vary in terms of the rural–urban migration rate, policy for the creation of protected areas, and transition rates between the different land-use classes

| Variable | Scenarios |

|---|---|

| 1. Prediction 2030 | 1.1 Project present trends |

| 2. Rural population | |

| Natality and mortality rates | 2.1 Natality and mortality rates of Argentina |

| Migration rate | 2.2 Emigration (rates of Misiones) |

| 2.3 High emigration (rates of Iguazu) | |

| 2.4 No migration (1970–2006) | |

| 2.5 No migration (2006–2030) | |

| 3. Policies | |

| Landscape planning | 3.1 Proposed landscape planning |

| Recovery | 3.2 100% Outflows mixed to unprotectedforest |

To analyze the potential effects of different demographic scenarios on land-cover changes, we created the 2.1 scenario that included the projected natality and mortality rates for Argentina for the period 2001 to 2030. To test the importance of migration rates, we ran the 2.2 scenario modeled with the average rural–urban migration rate for the last 30 years in Misiones (−23.2‰) (Table 1); which represents an “emigration scenario”. The 2.3, more extreme scenario (rural depopulation), was created using the Iguazu migration rate, which was the department with highest rural emigration between 1991 and 2001 (−73‰); this scenario can be considered representative of a rapid change towards an economy based on international tourism instead of local agriculture production. Two scenarios of no migration were created to serve as a comparison to quantify the role of rural emigration on forest conservation. To assess the past and future role of rural migration on deforestation, we ran the 2.4 scenario suppressing the rural migration flow between 1970 and 2006, and the 2.5 scenario in which we suppressed the rural migration flow between 2006 and 2030.

To test the implications of landscape-planning policies, we created two scenarios; the 3.1 scenario simulates the proposed provincial landscape planning law for Misiones by including in each department the area proposed to be protected after 2010 (i.e., moving them to the protected areas stock). The 3.2 scenario assumed that all outflows from Mixed recover to Unprotected Forest simulating the transition forest process observed in other regions. In these two last scenarios, all demographic variables were held constant using values from the current trends scenario (scenario 1.1 in Table 2).

In addition, we tested the implications of rural emigration for the urban population by quantifying the percent of urban population growth due to rural emigrants, assuming all rural emigrants move to cities within Misiones.

Results of Modeling Experiments

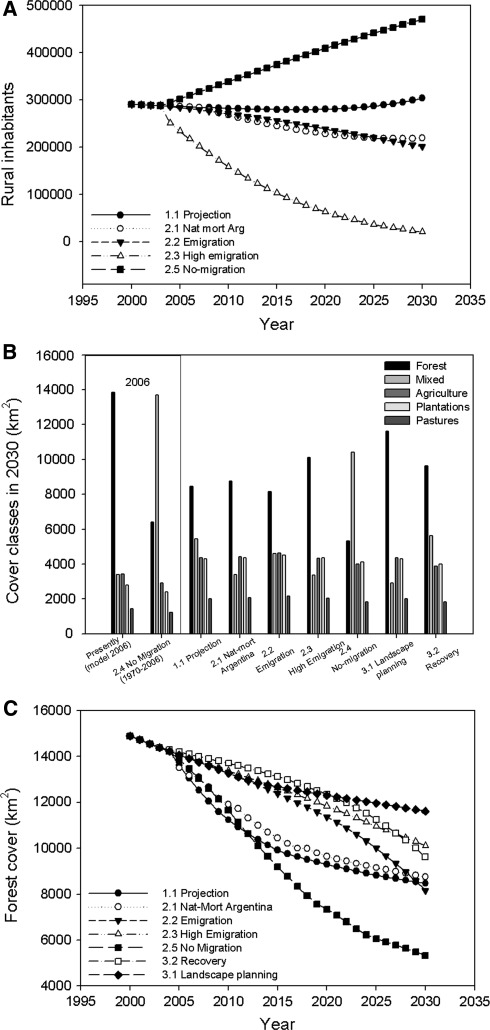

The two rural emigration scenarios (scenarios 2.2 and 2.3 in Table 2) indicate that the rural population of Misiones will stabilize or decline over the next 25 years. In contrast, the no-migration scenario (scenario 2.5 in Table 2) predicts a rural population of approximately 470,000 by 2030 (Fig. 4A), 185,000 more than the current 285,000 rural inhabitants. These scenarios suggest that during the following 30 years, the change in rural inhabitants could range from close to zero to approximately 66% more than in the present, indicating the large effects that migration can have on rural population size.

Fig. 4.

Changes in rural population (A), land cover (B), and forest cover (C), for the different scenarios. Note: in B that the presently and presently without migration scenarios (1.1 and 2.4 scenarios in Table 2) show cover classes in 2006, while the rest show cover classes in 2030 (future scenarios). In C note that the y axis starts at 4,000

The different scenarios show the impact of rural population on forest cover (Fig. 4B). The no-migration scenario between 1970–2006 (scenario 2.4) would have resulted in the conversion of 7,454 km2 of forest to mixed uses, which would have reduced forest cover to less than 50% of the area in 2006 (Fig. 4B, C). In all future scenarios, native forest cover is expected to decrease substantially by 2030, but the amount varies substantially among the scenarios. In 2006, approximately 50% of the total province area was forest area, but by 2030, forest cover will be reduced by 18 to 39%, depending on the scenario (Fig. 4B, C). The 3.1, landscape planning, scenario predicted the highest forest cover by the end of the study period (11,612 km2, 39%). The 2.3, high-emigration scenario (based on Iguazú rates) yielded the second highest forest cover (10,115 km2, 33%) by 2030. The 3.3, regeneration scenario resulted in the third greatest forest area (9,627 km2, 30%) followed by the 2.1 Argentina natality and mortality rates scenario (8,762 km2, 29%) (Fig. 4B, C). These four scenarios predict a gain of forest between 1,460 and 3,450 km2 relative to the 1.1, current trends scenario, and between 1,160 and 3,146 km2 more forest with respect to the 2.2, Misiones emigration rate scenario (Fig. 4B, C). The 2.5, no-migration scenario, which dramatically increases the rural population, had a major negative impact on forest cover (i.e., 5,333 km2 remnants in 2030, 18%) (Fig. 4B, C).

In the 3.1, landscape-planning scenario, forest cover would be 11,612 km2 (37% of provincial area) by 2030, 2,477 km2 as Unprotected Forest and 9,135 km2 in Protected Areas (Fig. 4B, C). In the 3.2, regeneration scenario, forest cover was 9,627 km2 (32% of provincial area). These results show that by 2030, forest cover is slightly greater in the policies scenarios compared to the most probable demographic scenarios (the 2.1, low natality and mortality rates and 2.3 high emigration rate).

The other land-cover classes were less affected by rural demographic dynamics (Fig. 4B), because of the weaker relationship between rural population change and the outflow from “Mixed” (r2 = 0.25). If the model follows the land-use class transition trends between 1970 and 2006, plantations could increase from the current 2,800 to 4,000–4,500 km2 in 2030 in all scenarios (Fig. 4B). This means a total forest cover (native forest + forest plantations) of 32% (9,460 km2) to 53% (15,923 km2) of province in 2,030 in the no-migration and landscape planning scenarios (2.5 and 3.1, respectively).

In 2006, approximately 80% (10,000 km2) of Misiones forest, including the least fragmented sectors, occurred in the six northern departments (Fig. 1). In the four most likely scenarios (Misiones emigration rates, Iguazu emigration rates, no-migration, and landscape planning; 2.2, 2.3, 2.5, and 3.1, respectively), native forest cover in this region will decline (Fig. 5A). The 3.1 landscape planning scenario was the most favorable for native forests, and resulted in an additional loss (2006–2030) of 1,160 km2 (Fig. 5A). Given that the northernmost departments have the fastest rural population growth, the highest deforestation rates, and the largest areas under protection, under some scenarios, the amount of forest available for deforestation disappears in a few years and forest cover becomes stable (Fig. 5B, G). The 2.2, Misiones emigration rate scenario resulted in a loss of 2,343 km2 of forest and 2.3, Iguazú emigration rate scenario predicted a loss of 1,978 km2 for the region by 2030. The 2.5, no-migration scenario is the most negative scenario, and it predicts a loss of 3,182 km2 of forest by 2030 for the northern region. In this scenario, all departments would rapidly lose unprotected forest, and Eldorado would lose all forest because it presently does not have any protected areas.

Fig. 5.

Changes in total forest cover for the six northern departments (A) and for each department separately (B–G). Note that the y axis has different scales for better visualization in each case

Between 1970 and 2001, approximately 20% of urban population growth was due to rural–urban migration, assuming that all rural migrants moved to cities in Misiones. As the proportion of rural population becomes smaller in the future, the relative contribution of rural migration to urban population growth between 2002 and 2030 will also become smaller: 5.45% in the 1.1, current trend scenario, 6.05% in the 2.2 Misiones emigration rate scenario, 6.53% in the 2.1 Argentina natality and mortality rates scenario, and 10.21% in the 2.3 Iguazu emigration rate scenario.

Discussion

The global population has increased from 3 billion in 1960 to 6 billion in 2000, and is expected to reach 9 billion by 2050. After this rapid period of growth, the population is expected to become more stable, and largely settled in urban areas (UNFPA 2007). This continuing increase in the human population and per-capita consumption, and the changes in diet are increasing the global demand for food and driving agricultural expansion. However, on the other hand, the concentration of modern agriculture on the most productive soils (Mather and Needle 1998) has favored the population shift from rural areas to urban centers. Understanding the effects of rural population on land-use change during this period is essential for predicting the future extent and configuration of natural ecosystems and their ecosystem services. Future deforestation in the Neotropics is likely to follow the ongoing trend of expanding industrial agriculture oriented to global markets, largely independently from local rural demography and concentrated in seasonal and flat regions such as the Chaco and Cerrado ecoregions (Fearnside 2001; Grau et al. 2005a, b). However, large areas, including the most humid and mountainous regions, often characterized by higher biodiversity, are likely to continue experiencing the effects of small-scale agriculture strongly associated with local rural population. This case study, in the Argentine Atlantic Forest may reflect how these systems could respond to socioeconomic globalization. Between 1970 and 2001 there was a strong positive relationship between the annual change in rural population and the deforestation rate in Misiones (Fig. 2), but rural emigration “reduced” deforestation by 24% in comparison with the “no-migration” scenario. If future emigration rates increase (e.g., emigration rate or high emigration rate scenarios), by 2030 deforestation will be reduced by 26% compared to the current trend scenario (scenario 1.1). In the extensive areas of the neotropics that are not suitable for modern agriculture due to steep slopes or poor soils (e.g., western Amazon, humid Andean slopes), the effects of rural population on forest change may be similar to Misiones. Our results indicate that in these areas, rural–urban migration can play a key role in conservation. Urbanization drivers such as international tourism and associated commerce activities, as in Iguazu, can greatly stimulate migration by providing jobs for rural migrants.

The Misiones example also shows the positive impact of land-use planning for forest conservation (i.e., 3.1. scenario) (Fig. 4). This scenario reflects new legislation that will encourage the creation of protected areas and promote forest restoration in priority areas. However, the implementation of this policy, as well as its financial and social costs, will depend on reducing conflicts with other land uses and the rural population. If protected areas are created with no reduction in rural population and no land-use intensification, this would inevitably lead to conflicts and the need for expensive protective measures. To ensure the success of this landscape planning legislation, it needs to be accompanied by agricultural extension efforts to help small landowners intensify their production. For example, the recovery scenario (3.2) represents a way to conserve a large forest proportion. Although it was not the trend in Misiones in the last decades (Izquierdo et al. 2008), it was documented in other tropical and subtropical regions (e.g., Grau et al. 2003; Klooster 2003) where there has been an opportunity to combine social and environmental improvements (UNFPA 2007; Aide and Grau 2004). Our results show that, in the case of Misiones, the only transition of all abandonment lands by projected emigration would result in forest recovery of ~1,500 km2 in 2030 without any further action.

In all our future scenarios, the forest cover is expected to decrease by 2030 (Fig. 4B, C), which is a major conservation concern (Wilcox and Murphy 1985). Our model is not spatially explicit, thus, we cannot evaluate the effects of forest spatial configuration on biodiversity conservation. However, Andrén (1994) showed that in landscapes with a high proportion of suitable habitat (more than 30%), the total area is more important than its spatial arrangement. Our results predict the loss of forest below this threshold only for scenarios 2.1, 2.2, and 2.5 (Argentine natality and mortality rates, 29%; emigration Misiones rates; and no migration, 18%); while the high emigration (2.3) and landscape planning scenario (3.1) predict 33 and 39% of forest cover, respectively). This strongly suggests that demographic and landscape planning could have important implication for biodiversity conservation.

Although our scenarios show that there are clear benefits of rural–urban migration for the conservation of natural ecosystems, migrants could increase social and environmental problems in urban areas. Despite that migrants often increase their living standards in comparison to the remaining rural population (Polèse 1998; Andersen 2002; UNFPA 2009), some authors have emphasized the negative aspects of rural–urban migration, including marginalization and poverty (e.g., Meyerson et al. 2007); therefore, an important challenge is to ensure that the conservation gains in the countryside are not undone by environmental and social costs in the urban environments. Our model did not directly assess the effects of rural migrants on urban environments in Misiones because there is no empirical information, but we indirectly assessed the potential impacts by quantifying the relative contribution of rural migrants to urban population growth. Since 1970, rural migration has contributed approximately 20% to urban growth, but in the future it would contribute only 5–10%. The declining impact of rural emigrants on the urban environment in Misiones is likely to be representative of many other regions in the Neotropics as the relative proportion of rural population (the source of rural migrants) decrease. These relatively low numbers imply that providing social programs to assist rural migrants in the cities and urban planning to reduce the social and environmental impacts of the migrants should not represent comparatively high costs.

Conclusions

This study shows that rural emigration in Misiones has contributed significantly to the conservation of native forests largely without any specific policy. Recent land-planning legislation could further help to protect forest resources by limiting future deforestation and directing agricultural and urban expansion to areas that have already been deforested (e.g., pasture lands, mixed use). In addition, the conservation and development balance can be enhanced by legislation for social programs that assist rural migrants in the cities (e.g., improve access to jobs, health service, education, and housing), and improving urban planning to reduce the social and environmental impacts of the migrants. These measures could help to conserve most of the remnant Atlantic Forest in Misiones, and might also serve as a model for regions with similar demography and land-use patterns.

Biographies

Andrea E. Izquierdo

is a postdoctoral associate in the CONICET and the Instituto de Ecologia Regional (IER) at the Universidad Nacional de Tucuman. She is an ecologist who has used satellite images, demographic analyses, and dynamics models to understand land-use change in the Atlantic Forest of Argentina and its socioeconomic causes. Her current research focuses on the implications of land use on ecosystem services in the subtropical forests of Argentina.

H. Ricardo Grau

is a researcher in the CONICET and the Instituto de Ecologia Regional (IER) at the Universidad Nacional de Tucuman. He is a geographer and an agronomist specialized in the ecology of disturbances and vegetation dynamics. His current research focuses on the effects of land use and climate change on neotropical ecosystems.

T. Mitchell Aide

is a professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Puerto Rico. He is a tropical ecologist who has worked mainly in Latin America. Most recently, his research has focused on how human and natural systems interact and affect the distribution of biodiversity in Latin America.

Contributor Information

Andrea E. Izquierdo, Phone: +54-0381-4255471, Email: aeizquierdo@gmail.com

Héctor R. Grau, Email: chilograu@gmail.com

T. Mitchell Aide, Email: tmaide@yahoo.com.

References

- Achard F, Eva HD, Stibig H, Mayaux P, Gallego J, Richards T, Malingreud J. Determination of deforestation rates of the world’s humid tropical forests. Science. 2002;297:999–1002. doi: 10.1126/science.1070656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aide TM, Grau HR. Globalization, migration, and Latin American ecosystems. Science. 2004;305:1915–1916. doi: 10.1126/science.1103179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen LE. Rural–urban migration in Bolivia: Advantages and disadvantages. La Paz, Bolivia: Instituto de Investigaciones Socio-económicas, Universidad Católica Boliviana; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Andrén H. Effects of habitat fragmentation on birds and mammals in landscapes with different proportions of suitable habitat: A review. Oikos. 1994;71:355–366. doi: 10.2307/3545823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen A, Kaimowitz D. Rethinking the causes of deforestation: Lessons from economic models. The World Bank. 1999;14:73–98. doi: 10.1093/wbro/14.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook BW, Bradshaw CJA, Koh LP, Sodhi NS. Momentum drives the crash: Mass extinction in the tropics. Biotropica. 2006;38(3):302–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00141.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet, L., and C. Noseda. 2000. Destination of the lands occupied by properties of the Province of Misiones. Unpublished Report. Montecarlo, Area de Extensión: INTA, EEA (in Spanish).

- Fearnside PM. Soybean cultivation as a threat to the environment in Brazil. Environmental Conservation. 2001;28:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Leal C, Gusmão-Câmara I. The Atlantic Forest of South America: Biodiversity status, threats and outlook. Washington, DC, USA: Center for Applied Biodiversity Science at Conservation International, Island Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparri NI, Grau HR. Regional patterns of deforestation in subtropical Argentina and its ecological context and socio-economic. In: Brown AD, Martinez Ortiz U, Acerbi M, Corcuera J, editors. Argentina environmental situation 2005. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Fundación Vida Silvestre; 2006. pp. 442–446. [Google Scholar]

- Geist HJ, Lambin EF. Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation. BioScience. 2002;52:143–150. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2002)052[0143:PCAUDF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo AR, Krauczuk ER, Arzamendia V, Povedano H. Critical analysis of protected areas in the Atlantic Forest of Argentina. In: Galindo-Leal C, Gusmão Câmara I, editors. The Atlantic Forest of South America: Biodiversity status, threats and outlook. Washington, DC, USA: Island Press; 2003. pp. 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Grau, H.R., and M. Aide. 2008. Globalization and land-use transitions in Latin America. Ecology and Society 13(2): 16. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss2/art16/.

- Grau HR, Aide TM, Zimmerman JK, Thomlinson JR, Helmer E, Zou X. The ecological consequences of socioeconomic and land-use changes in postagriculture Puerto Rico. BioScience. 2003;53(12):1159–1168. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[1159:TECOSA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grau HR, Aide TM, Gasparri NI. Globalization and soy-bean expansion into semiarid ecosystems of Argentina. Ambio. 2005;34:265–266. doi: 10.1639/0044-7447(2005)034[0265:gaseis]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau HR, Gasparri NI, Aide TM. Agriculture expansion and deforestation in seasonally dry forests of north-west Argentina. Environmental Conservation. 2005;32:140–148. doi: 10.1017/S0376892905002092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SB. The logic of livestock and deforestation in Amazonia. BioScience. 1993;43(10):687–695. doi: 10.2307/1312340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra JM, Boucher TM, Ricketts TM, Roberts C. Confronting a biome crisis: Global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecology Letters. 2005;8:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00686.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Census of Population and Housing 1947. Argentina: Buenos Aires; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- National Census of Population and Housing 1960. Argentina: Buenos Aires; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- National Census of Population and Housing 1970. Argentina: Buenos Aires; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- National Census of Population and Housing 1980. Serie D: Población. Argentina: Buenos Aires; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- National Census of Population and Housing 1991. Argentina: Buenos Aires; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- National Census of Population and Housing 2001. Argentina: Buenos Aires; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, A.E., C.D. De Angelo, and T.M. Aide. 2008. Thirty years of human demography and land-use change in the Atlantic Forest of Misiones, Argentina: An evaluation of the forest transition model. Ecology and Society 13(2): 3. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss2/art3/.

- Jepson WA. A disappearing biome? Reconsidering land cover change in the Brazilian savanna. Geographical Journal. 2005;171:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4959.2005.00153.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klooster D. Forest transitions in Mexico: Institutions and forests in a globalized countryside. Professional Geographer. 2003;55:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, P. 1994. The conservation of natural resources and man in the Selva Paranaense. Technical Bulletin No 2. Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina, Buenos Aires, Argentina (in Spanish).

- Laurance WF, Albernaz AKM, Fearnside PM, Venticinque EM, Hadley S. Predictors of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Science. 2002;297:737–748. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5582.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzi GA. Industrial development missions. A critical perspective to the discussion with a view to territorial integration. Posadas, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Misiones; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mather AS, Needle CL. The forest transition: A theoretical basis. Area. 1998;30:117–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.1998.tb00055.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson FA, Merino L, Durand J. Migration and environment in the context of globalization. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2007;5:182–190. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[182:MAEITC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier, R.A., P. Robles-Gil, M. Hoffmann, J.D. Pilgrim, T.M. Brooks, C.G. Mittermeier, J.L. Lamoreux, and G. Fonseca. 2004. Hotspots revisited: Earth’s biologically richest and most endangered terrestrial ecoregions. Mexico City: CEMEX.

- Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DM, Dinerstein E. The Global 200: Priority ecoregions for global conservation. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2002;89:125–126. doi: 10.2307/3298564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Placci G, Di Bitetti M. Environmental situation on the Upper Parana Atlantic Forest ecoregion. In: Brown A, Martínez Ortiz U, Acerbi M, Corcuera J, editors. Argentina environmental situation. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Fundación Vida Silvestre Argentina; 2005. pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Polèse M. Urban and regional economy. Introduction to the relationship between territory and development. Cartago, Costa Rica: Libro Universitario Regional; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan S. Fewer people may not mean more forest in Latin American forest frontiers. Biotropica. 2007;39(4):443–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00288.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). 2007. State of the world population. Unleashing the potential of urban growth. http://www.unfpa.org/swp/swpmain.htm.

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). 2009. State of the world population. Facing a changing world: women, population and climate. http://www.unfpa.org/swp/2009/en/.

- Walker R. Land use transition and deforestation in developing countries. Geographical Analysis. 1987;19(1):18–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-4632.1987.tb00111.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox BA, Murphy DD. Conservation strategy: The effects of fragmentation on extinction. American Naturalist. 1985;125:879–887. doi: 10.1086/284386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SJ, Muller-Landau HC. The future of tropical forest species. Biotropica. 2006;38:287–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00154.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]