Abstract

Leadership is an essential ingredient in reaching international agreements and overcoming the collective action problems associated with responding to climate change. In this study, we aim at answering two questions that are crucial for understanding the legitimacy of leadership in international climate change negotiations. Based on the responses of three consecutive surveys distributed at COPs 14–16, we seek first to chart which actors are actually recognized as leaders by climate change negotiation participants. Second, we aim to explain what motivates COP participants to support different actors as leaders. Both these questions are indeed crucial for understanding the role, importance, and legitimacy of leadership in the international climate change regime. Our results show that the leadership landscape in this issue area is fragmented, with no one clear-cut leader, and strongly suggest that it is imperative for any actor seeking recognition as climate change leader to be perceived as being devoted to promoting the common good.

Keywords: Climate change, Leadership, Legitimacy, Followers, Views on leadership, COP

Introduction

There is a widespread consensus among scientists that climate change poses an acute threat to humanity. Political leaders across the globe have responded to the alarm and negotiations aimed at finding effective measures to address the climate change challenge are currently taking place within the framework of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). However, progress thus far has been slow and the prospects of reaching a comprehensive agreement appear bleak.

Research has shown that leadership is an essential ingredient for reaching international agreements and overcoming the collective action problems associated with global environmental problems, such as biodiversity and climate change (Sjöstedt 1994; Tallberg 2006; Mitchell 2010; Nye 2010). Leadership makes a difference by establishing a “relationship of influence in which one actor guides or directs the behavior of others toward a certain goal” (Underdal 1994, p. 178). When confronting complex transnational problems in which the stakes are high and solutions can be blocked by collective action problems, leadership is essential. Leadership can be important by providing a model others may want to emulate, removing uncertainty about whether the leader is actually devoted to meaningful action, or creating incentives that may persuade others to follow.

Seen from a traditional leadership perspective, the limited success in mobilizing global action is somewhat puzzling given that there has been no shortage of self-proclaimed leaders in the field of climate change. Important actors like the US (AFP 2009) and the EU (Vogler 2009; Kilian and Elgström 2010; Parker and Karlsson 2010) have indeed pledged to exercise the leadership thought necessary in order for the UNFCCC efforts to bear fruit. When seeking to understand why so little progress has been made, focus has primarily been directed towards the words and deeds of the leaders. However, there can be no leaders without followers (Underdal 1994; Karlsson et al. 2011) and both parties to this equation are required for successful leadership to materialize. Rather than focusing solely on the flaws and failures of the self-proclaimed leaders, we should therefore pay more attention to the perceptions of the potential followers as we attempt to make sense of the developments that have taken place in the field of international climate change cooperation over the last several years.

Historically, leadership on climate change has primarily been exercised by the US and the EU. In the last 30 years both have attempted to exercise leadership on this issue. However, in recent years the landscape of international environmental cooperation has changed, with new actors and coalitions—e.g. China and the BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) coalition—now vying for leading roles (Carin and Mehlenbacher 2010; Christoff 2010; Karlsson et al. 2011). This means that the supply side of the leadership landscape is more fragmented than ever. The question is whether any of these leadership candidates are actually recognized as leaders by the potential followers, or if we simply have a number of self-proclaimed leaders with no real support?

In this article, we attempt to answer two questions that are crucial for understanding the legitimacy of leadership in international climate change negotiations. Based on unique survey data collected at three consecutive Conference of Parties (COP) meetings—in Poznań 2008, Copenhagen 2009 and Cancún 2010—we seek first to document whether there are in fact any actors that can claim to be seen as legitimate leaders in the field of climate change. Who among the leadership candidates are recognized as leaders, and to what extent? Second, we aim to shed light on the factors that influence whether or not a leadership candidate is supported as a leader.

By focusing on which actors are recognized as leaders by UNFCCC negotiation participants, and why, this study seeks to make an important contribution to leadership theory which hitherto has been focused nearly exclusively on the supply-side of leadership and the words and deeds of would-be leaders (Ringius 1999; Gupta and Ringius 2001; Vogler 2005; Groenleer and Van Schaik 2007; Schreurs and Tiberghien 2007). To fully understand the role played by leadership in international climate change negotiations it is, of course, valuable to have a firm understanding of what aspiring leaders actually say and do in their efforts to affect the behavior of other actors. However, it is not enough to simply focus on the goals, strategies, and leadership modes of self-declared leadership contenders. It is also important to investigate which actors are actually recognized and accepted as leaders. A mismatch between the supply and demand of leadership may mean that potential followers will be less willing to let their behavior be guided by specific leadership gambits or undermine leadership efforts to forge joint solutions to common problems. Therefore, to gain a more complete picture of leadership, we must also put a spotlight on follower perceptions, the factors associated with leadership recognition, and legitimacy.

There are indeed a few studies (Gupta and van der Grijp 1999; 2000; Elgström 2007; Schirm 2009; Kilian and Elgström 2010 that examined the demand side of leadership, but important empirical and theoretical gaps remain to be filled. In an earlier study (Karlsson et al. 2011), we were able to provide a snap-shot of the demand-side of leadership at the 2008 COP-14 conference. By drawing on data from the three consecutive surveys, we now have a much deeper evidentiary base from which to draw conclusions about the leadership landscape. To the best of our knowledge, this study is unique as it is able to not only report which actors are seen as leaders, but also charts how leadership perceptions evolve over time as well as shedding light on which factors motivate leadership recognition.

The data used in this study stem from surveys conducted at the three consecutive COP meetings, 2008–2010. The data set consists of a total of 1254 completed surveys. Surveys were distributed in person at the conference venue during the first week and during the high-level segment of week two. Respondents were asked to indicate which actor or actors they believed to be leaders in the field of climate change as well as pointing out which factors motivate them to support an actor as leader. The survey was primarily focused on collecting a representative sample of the two largest and most important categories of COP participants: on the one hand members of party delegations, such as negotiators and representatives of government agencies, and on the other NGO representatives and researchers. Members of the two smallest participant categories, media and representatives of UN, and other intergovernmental organizations, were not our primary focus but respondents from these groups of participants are also included in the data set.

The remainder of this article is organized into three main sections and a conclusion. In the first section, we discuss the importance of leadership and present our analytical framework. The second section is devoted to examining if there are any legitimately recognized climate change leaders and shows how leadership perceptions have evolved from COP-14 to COP-16. In the third section, we seek to chart what motivates the potential followers to support different actors as leaders. Finally, in the conclusion, we discuss what our findings imply for the ability to exert leadership in international climate change negotiations.

Examining Leadership

The role played by leadership in international negotiations can take three different forms. Structural leadership means that a leader deploys power-resources that create new incentives and changes the costs and benefits associated with different avenues for action in a particular issue area (Young 1991, p. 288–289; Underdal 1994, p. 186). This type of leadership flows from an actor’s aggregate power and can be pursued through coercion or constructive inducements. By engaging in directional leadership and making the first move, a leader provides a model that others may want to emulate. Demonstrating a commitment to act, also removes uncertainty about whether the leader is actually devoted to the undertaking rather than just engaging in cheap talk (Underdal 1994, p. 183–185). Idea-based leadership (also referred to as entrepreneurial, intellectual or instrumental), is concerned with problem naming and framing and the promotion of solutions to collective problems. This type of leadership is characterized by agenda setting efforts and includes discovering and proposing joint solutions to collective problems.

Providing good ideas or setting a good example which others may follow are important leadership tools according to the literature, but they are unlikely to be sufficient in guaranteeing a positive outcome. Idea-based and directional leadership usually need to be accompanied by the bargaining leverage that stems from structural power. On the other hand, relying solely on structural leadership is rarely a recipe for success, simply because it is difficult for any one actor to muster sufficient power-resources to make this a viable strategy. If the efforts of a leader are to be successful, it will often take the “contributions of different forms of leadership” (Young 1991, p. 303).

In this study, we will examine the legitimacy of leadership in the field of climate change. A number of actors, including the EU and the US, have in recent years declared their intention to act as leaders within the UNFCCC regime. The EU in particular has invested much time and effort to brand itself as a climate change leader. The EU’s goal, as it states in its own words, is nothing short of “leading global action” against climate change “to 2020 and beyond” (Council of the European Union 2007, p. 10–11). It is one thing, however, to declare yourself a leader and quite another to actually be recognized as such by potential followers. In our search for legitimate leaders in the field of climate change, we will focus on the under-researched demand side of the leadership relationship and the perceptions of the followers.

By legitimate leaders, we mean the degree to which actors asserting leadership positions are actually recognized as leaders by the prospective followers. It is important to make clear that, our aim is not to chart the levels of support for the different policies and leadership services offered by potential leaders. What we seek to establish is simply if there are any actors that are currently seen as leaders on climate change inside the climate change regime. We hereby seek to examine to what extent there are socially legitimate leaders, in terms of actual recognition, in this issue area.

In general, two main views of legitimacy can be identified (cf. Karlsson 2001, p. 107–108; Buchanan and Keohane 2006, p. 405). According to the first, the legitimacy of a regime, an institution, or a leader is determined by examining to what degree a certain standard or criterion is met, e.g., democracy, efficiency, or the rule of law. This view of legitimacy can be labeled normative or formal (Weiler 1991, p. 2469) legitimacy. The other main view of legitimacy may be labeled social or empirical, since it originates from the subjective attitudes and beliefs of individuals. Social legitimacy thus “connotes a broad empirically determined societal acceptance” (Weiler 1991, p. 2469) of a regime, an institution or a leader. This study draws from the second view of legitimacy by examining which actors, if any, are recognized as leaders on climate change and which factors determine leadership support. We acknowledge that simply being recognized as a leader is not a sufficient criterion for an actor to be deemed as a legitimate leader. It also matters whether or not potential followers accept an actor’s bid for leadership as justified (cf. Bodansky 1999, p. 601). Nonetheless, in our view, recognition is necessary for a leader to enjoy legitimacy in the sociological sense. Examining leadership recognition can thus be seen as an important first step towards establishing the existence or absence of legitimate climate change leaders.

Attempting to answer the article’s second question takes us even further into uncharted territory. Previous leadership research has not, as far as we know, gathered evidence on what motivates followers to recognize different actors as leaders. Past scholarship on the main form leadership takes in international negotiations does, however, provide a useful departure point for formulating rival hypotheses on what motivates potential followers to support particular leaders. As noted above, there are three main modes of leadership: structural, directional, and idea-based. In order to better understand the followers’ reasons for choosing to support specific leaders, we asked COP participants to indicate how important they believed different leadership characteristics to be. We provided respondents with a list of factors that could be seen as important when it comes to supporting a particular leader. Some of the factors were derived directly from the different modes of leadership. In order to tap into the significance of structural leadership in this context, we asked respondents to indicate to what extent a leader’s “ability to provide resources and inducements to address a problem” was important for their decision to support a particular leader. In a similar fashion, we examined the importance of directional (“The leader’s ability to demonstrate a credible domestic climate change policy”) and idea-based leadership (“The leader’s ability to provide new ideas and solutions for dealing with the climate change problem”).

In addition to features linked to an actor’s ability to act as a structural, directional or instrumental leader, we provided respondents with two additional factors. In order to distinguish the leadership from pure power politics, leadership theory often includes pursuit of some common good as a defining characteristic of leadership (Underdal 1994, p. 178–9; Malnes 1995, p. 92). Hence, we also asked respondents to indicate the importance of the “leader’s overall commitment to solving the climate change problem”. Finally, as we should not underestimate the extent to which self-interest comes into play as a factor determining whether or not prospective followers decide to support a particular leader, we asked COP participants to what extent a leader’s “promotion or defense of my country’s interests” was important for their decision to support a particular leader.

Having laid out our objectives and analytical concerns, in the following sections we present and analyze our findings. We start by looking for legitimate leaders in the field of climate change.

Looking for Legitimate Leaders

In order to establish which actors are recognized as playing a leading role in the climate negotiations, we posed the following open-ended question to respondents: “Which countries, party groupings, and/or organizations have, in your view, a leading role in climate negotiations”?

According to our results, the EU, the US, China, and G-77 were the actors most frequently mentioned as playing a leading role in the field of climate change. Other party groupings (e.g. the BASIC and the BRIC countries and the Alliance of Small Island States) as well as individual countries like India and Brazil were also recognized as leaders by more than 10% of the respondents, but no other actor came close to the same levels of recognition as the four actors included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Leadership recognition 2008–2010, general trend for main actors (percentages)

| Poznań 2008 | Copenhagen 2009 | Cancún 2010 | Diff. Cop 2008–2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU as leader | 62 | 46 | 45 | −17 |

| China as leader | 47 | 48 | 52 | +5 |

| G-77 as leader | 27 | 22 | 19 | −8 |

| US as leader | 27 | 53 | 50 | +23 |

| n | 163 | 454 | 634 |

The first conclusion to be drawn from Table 1 is that there is no single, undisputed leader on climate change. In Copenhagen and Cancún, we see a fragmented leadership landscape with three leadership candidates—the EU, the US and China—being recognized as leaders by roughly half of the respondents. If we look back at the situation in Poznań, we can register fairly dramatic changes as the recognition of the EU has declined from 62 to 45%, whereas the opposite trend is noticeable for the US with figures increasing from 27 to 50%. It is also worth noting that China is currently holding on to the number one position as 52% of respondents in Cancún reported that they saw China as a leading actor in the climate change negotiations. The recognition of G77 as leader has declined the last couple of years and only 19% of Cancún respondents saw this party grouping as leader on climate change.

The EU which has made its mission to brand itself as the leader on climate change was indeed the actor most commonly recognized as leader in Poznań, but has since lost the number one position and in Cancún slightly less than half of the respondents reported that they saw the EU as a leader in the field of climate change. The big decline in leadership recognition for the EU, from 62 to 46%, however, occurred between Poznań and Copenhagen. Since Copenhagen, the recognition for the EU seems to have stabilized or even be on the rise again, at least among some important participants, such as negotiators (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Actors recognized as leaders 2008–2010, by primary roles (percentages)

| EU as leader | US as leader | China as leader | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Negotiator | 62 | 45 | 54 | 16 | 52 | 46 | 68 | 53 | 50 |

| Government | 54 | 34 | 46 | 22 | 36 | 50 | 30 | 42 | 52 |

| NGO | 55 | 46 | 45 | 33 | 54 | 49 | 45 | 40 | 50 |

| Research | 85a | 53 | 51 | 31a | 49 | 62 | 31a | 38 | 57 |

| Business | 75a | 54 | 51 | 33a | 65 | 58 | 50a | 60 | 71 |

| UN and IGO | 56a | 45 | 34 | 31a | 65 | 38 | 31a | 60 | 34 |

| Media | 80a | 60 | 42 | 20a | 80 | 53 | 20a | 60 | 56 |

| All | 62 | 46 | 45 | 27 | 53 | 50 | 46 | 47 | 52 |

aThese subgroups contain less than 20 respondents and the results should therefore be interpreted with caution

An important dimension of the demand for leadership is to what degree the leadership contenders on climate change are recognized as leaders outside their borders. In order to exercise legitimate leadership effectively at the global level, an actor needs to be acknowledged as a leader, not only by a small subset of close supporters, but also by the potential followers from different geographical regions. Table 2 clearly shows that geographical belonging matters. For example, whereas 45% of all respondents in Cancún viewed the EU as a leader, 63% of EU-citizens did so. It is also interesting to note that respondents from Oceania to a large extent have turned away from the EU and instead are looking to the US and China for leadership. The only region where recognition of the EU as a leader has increased in recent years is actually Africa.

Table 2.

Leader recognition 2008–2010, by geographical region (percentages)

| EU as leader | US as leader | China as leader | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| Africa | 38 | 36 | 48 | 24 | 47 | 49 | 62 | 36 | 48 |

| Asia | 63 | 31 | 40 | 14 | 35 | 39 | 35 | 39 | 48 |

| Europe | 75 | 65 | 63 | 42 | 68 | 59 | 52 | 54 | 64 |

| North America | 54 | 53 | 35 | 38 | 63 | 50 | 46 | 47 | 48 |

| South & Latin America | 57 | 47 | 44 | 14 | 29 | 48 | 64 | 47 | 49 |

| Oceania | 50 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 40 | 57 | 17 | 36 | 50 |

| All | 62 | 46 | 45 | 27 | 53 | 50 | 47 | 48 | 52 |

The recognition of the US and China as leaders on climate change is fairly evenly distributed across geographical regions, but it is interesting to note that it is European respondents that are most likely to see China as a leader. It is also worth noting that only half of the respondents from North America identify the US as a leading actor.

If we break down the data by role and focus on the difference in leadership recognition reported by the two most important categories of respondents, negotiators and government representatives, we find some interesting patterns.

As is seen from Table 3, the recognition of EU as leader among the real insiders to the UNFCCC process, i.e., the negotiators and government representatives, actually increased between Copenhagen and Cancún. This stands in sharp contrast to perceptions among the media where we see that estimations of the EU as climate leader have plummeted. It is also noteworthy that among negotiators, the recognition of the US as leader dropped twice as much, from 52 to 46%, as it did among the respondents as a whole.

Exploring the Factors Determining Leadership Support

Now that we have documented which actors are recognized as climate change leaders, it is time to turn our attention to the determining factors associated with the legitimacy of leadership. In order to explore what motivates followers to support different actors as leaders, respondents were asked to what extent they agreed—on a scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly)—with a number of statements concerning which factors could be important for choosing to support a particular leader. As explained above, we aimed to examine to what extent an actor’s perceived ability to engage in structural, directional, or idea-based leadership affected the likelihood of it being recognized as leader. Besides exploring factors derived directly from the three modes of leadership, we also asked respondents to indicate the importance of the leader’s commitment to the common good as well as to what extent self-interest came into play.

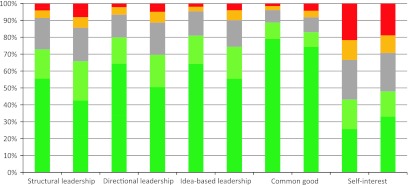

Below we report the main results from our survey probing the importance of five factors associated with choosing which leader to support. Figure 1 clearly shows that overall commitment to solving the climate change problem is the most important reported factor that motivates the support of a particular leader. Put differently, an actor aspiring to gather widespread support as leader needs to work for, or at least be perceived as working for, the common good. A vast majority of respondents—79% in Copenhagen and 74% in Cancún—indicated that this is indeed an important factor when opting to back a specific leader.

Fig. 1.

Importance of factors for leadership support 2009 and 2010 among delegates (percentage). For each factor the first column displays the Copenhagen results and the second the Cancún results. The importance of the factors for supporting a particular leader are measured on a scale from 1 (respondents disagree strongly) to 7 (respondents agree strongly). In the figure, the share of “1” and “2” responses is displayed in red at the top of the column while the share of “6” and “7” responses is displayed in deep green at the bottom. The number of respondents was 151 in Copenhagen and 270 in Cancún

At the other end of the spectrum, our respondents reported that self-interest was the least important factor when selecting a leader. At COP-15 only 25% of respondents judged the promotion of their country’s interests to be important; while at COP-16 the number was 33%, once again the lowest of all the factors. As for the three leadership modes, it is evident that the ability to engage in structural leadership by providing “resources and inducements to address the problem” was rated as less important by respondents than idea-based or directional leadership.

When we compare our results from 2009 and 2010, we see that our respondents’ perceptions concerning the importance of the different factors remained stable; the ranking order between the five remained unchanged between COP-15 and COP-16. Commitment to the common good was deemed the most important factor followed by idea-based, directional and structural leadership, while self-interest was seen as the least vital factor when selecting which leader to support. It is, however, possible to detect some interesting changes between Copenhagen and Cancún. The reported importance of directional leadership decreased from 65 to 50%. We can also see a corresponding decline for idea-based leadership—from 65 to 56%—as well as for structural leadership which fell from 55 to 43%. The importance of self-interest, on the other hand, has increased with 33% of respondents in Cancún agreeing that the promotion of their country’s interests was an important factor for their choice to support a particular leader—the corresponding number in Copenhagen being 25%. The fact that self-interest has become an increasingly important factor—should this intensify into a growing trend—could prove to be problematic for the international climate negotiations, if it resulted in a situation in which the various leadership candidates advocated primarily on behalf of defined constituencies, rather than acting as champions for the common good. However, we are still a long way away from such a state of affairs. The promotion of the common good is still, by far, the most important factor when respondents decide whether to support a particular leader, even if the percentage of respondents who said that the promotion of the common good was important decreased from 79 to 74% between Copenhagen and Cancún.

Are there any marked differences between respondents from different geographical regions, when it comes to which factors they see as important when opting to support a particular leader? While there are only small differences when it comes to the value of promoting the common good, a substantial variation can be detected when it comes to the significance respondents attach to a leader they believe will promote their country’s interests.

When comparing the relative importance of the three modes of leadership among respondents from different geographical regions, it is noteworthy that COP participants from Africa as well as South and Latin America are more impressed by structural leadership than the average respondent. In contrast, respondents from Oceania tend to disregard resource and inducement provision when backing a leader. When looking at directional leadership we find only minor differences, whereas respondents differ substantially when it comes to assessing the importance of idea-based leadership. Respondents from South and Latin America and Oceania see this factor as being of almost the same importance as a leader’s overall commitment to solving the climate change problem. Roughly three quarters of COP participants from these regions highly valued idea-based leadership, while roughly half of the respondents from other regions did so.

However, the most striking difference between respondents from different geographical regions is linked to the importance of self-interest. As the data in Table 4 show, respondents from those regions that are likely to suffer the most immediate and severe consequences of climate change, are much more likely to take the promotion of their country’s interests into account when deciding to support a leader. More than half of the respondents from Oceania and 42% of COP participants from Africa and South and Latin America rated this as an important factor, whereas only 23% of European and 33% of North American respondents did so.

Table 4.

Importance of factors for leadership support 2010, by geographical region (percentages)

| Structural leadership | Directional leadership | Idea-based leadership | Common good | Self interest | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | |

| Africa (n = 69) | 52 | 9 | 48 | 4 | 59 | 4 | 83 | 4 | 42 | 16 |

| Asia (n = 123) | 43 | 5 | 45 | 3 | 50 | 4 | 71 | 5 | 36 | 16 |

| Europe (n = 156) | 38 | 7 | 54 | 3 | 53 | 1 | 81 | 1 | 23 | 23 |

| North America (n = 161) | 43 | 11 | 52 | 9 | 54 | 6 | 71 | 5 | 33 | 19 |

| South & Latin Am. (n = 83) | 51 | 10 | 59 | 7 | 74 | 7 | 79 | 8 | 42 | 25 |

| Oceania (n = 13) | 23 | 8 | 62 | 0 | 77 | 0 | 77 | 0 | 54 | 8 |

| All | 43 | 8 | 50 | 5 | 56 | 4 | 74 | 4 | 33 | 19 |

The importance of the factors for supporting a particular leader are measured on a scale from 1 (respondents disagree strongly) to 7 (respondents agree strongly). For each of the five factors, the first column, “High,” displays the share of respondents answering with a “6” or “7,” thus indicating a high degree of importance for this factor. The second column, “Low,” displays the share of respondents answering with a “1” or “2,” thus indicating a low degree of importance for this factor

When we break down the data by role, we find only minor differences between the two most important groups of respondents, i.e., negotiators and government representatives. The only real difference was that negotiators attached more importance to directional leadership, while government representatives were more inclined to see idea-based leadership as a key factor.

More notable differences present themselves when we compare negotiators and government representatives to other group of respondents, especially when it comes to how they judged self-interest as a decisive factor motivating leadership support.

As Table 5 reveals, negotiators and government representatives tend, quite naturally, to attach more importance than the average respondent to the promotion of their country’s interests, when deciding to back a particular leader. However, they also saw devotion to the common good as paramount, only among NGO representatives and members of the research community did we find a higher percentage of respondents who rated this as an important factor. This means that in order to secure widespread support and recognition as a legitimate leader among these groups of key actors, i.e. negotiators and government representatives, a would-be leadership candidate must be cognizant that promoting the interests of other countries matter for garnering leadership support. However, it is obvious that the promotion of a country’s (or a group of countries’) interests should not be allowed to compromise a leader’s ability to promote the common good, if said leader is striving to secure widespread support. The perceived overall commitment to solve the climate change problem is clearly the number one asset if one aspires to be recognized as a legitimate leader.

Table 5.

Importance of factors for leadership support 2010, by role (percentages)

| Structural leadership | Directional leadership | Idea-based leadership | Common good | Self interest | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | |

| Negotiator (n = 142) | 42 | 8 | 52 | 2 | 49 | 3 | 75 | 5 | 43 | 10 |

| Government (n = 131) | 44 | 7 | 47 | 1 | 57 | 3 | 76 | 6 | 46 | 11 |

| NGO (n = 181) | 45 | 7 | 60 | 3 | 63 | 4 | 81 | 3 | 22 | 28 |

| Research (n = 40) | 42 | 11 | 55 | 2 | 46 | 2 | 80 | 2 | 22 | 19 |

| Business (n = 50) | 41 | 9 | 45 | 11 | 60 | 0 | 67 | 8 | 29 | 17 |

| UN and IGO (n = 32) | 47 | 12 | 35 | 9 | 45 | 16 | 63 | 12 | 32 | 28 |

| Media (n = 40) | 38 | 7 | 46 | 12 | 53 | 2 | 65 | 5 | 34 | 14 |

| All | 43 | 8 | 50 | 5 | 56 | 4 | 74 | 4 | 33 | 19 |

The importance of the factors for supporting a particular leader are measured on a scale from 1 (respondents disagree strongly) to 7 (respondents agree strongly). For each of the five factors, the first column, “High,” displays the share of respondents answering with a “6” or “7,” thus indicating a high degree of importance for this factor. The second column, “Low,” displays the share of respondents answering with a “1” or “2,” thus indicating a low degree of importance for this factor

Conclusions

This article set out to examine the legitimacy of leadership in the international climate change negotiations. More specifically, we asked two questions: are there any legitimate climate change leaders and what factors matter most, when selecting and supporting a leader?

Based on the results from our survey, we conclude that we are currently facing a fragmented leadership landscape within the field of climate change. Between Poznán and Copenhagen we witnessed a dramatic change in leadership recognition, with the US almost doubling its support, whereas recognition of the EU dropped significantly. This new situation with roughly an equal size of recognition for the EU, the US, and China was confirmed by the data from Cancún. The EU, the US and China are indeed the Big Three, when it comes to who is seen as climate change leaders. However, all three of the main leadership contenders are at the moment struggling to gain recognition as leaders by even a majority of respondents and therefore the legitimacy of their leadership bids can rightfully be called into question. The limited levels of leadership recognition must be especially disappointing for the EU which, as a result of its 2008 climate change legislation, is on paper by far the most ambitious climate change mitigator.

Our survey results, which were remarkably stable and consistent between groups and across both years, provided us with a number of important findings regarding which factors inspire prospective followers to support particular leaders. When comparing respondents from different geographical regions, occupying different roles at the COP meetings we found only a few noteworthy differences. Significantly, it was respondents from vulnerable regions most likely to suffer the worst consequences from climate change, which attached the most importance to a leader’s ability to promote their countries’ national interests. It is also striking that self-interest mattered more for negotiators and government representatives than for the average respondent. Moreover, the most important change between the Copenhagen and Cancún results was that the self-interest factor gained somewhat in importance.

These differences aside, the lack of variation between different groups of respondents is striking. For example, the ranking order when it comes to assessing the importance of the different factors that determine leadership support are almost identical between respondents from different geographical regions. This indicates that it is indeed possible to make meaningful comparisons between different groups of respondents when it comes to who they recognize as climate change leaders. It does not, in other words, appear to be the case that different actors attach substantially different meanings to leadership. In short, our results indicate that COP participants have very similar understandings of what it means to be a leader, even if they have different views on how various actors perform as leadership candidates.

The number one conclusion to be drawn from our data is that the evidence strongly suggests that it is imperative for any actor seeking recognition as leader to be perceived as being devoted to promoting the common good. Regardless of geographical origin, roughly three quarters of all respondents attached great weight to a leader’s overall commitment to solving the climate change problem. No other factor comes even close to being as essential for leadership support. This finding also sheds light on how the fragmented leadership landscape should be interpreted. The fact that all three leadership candidates are struggling to find widespread recognition signifies that the EU, the US, and China all have more work to do if they want to convince prospective followers that they are genuinely dedicated to solving the climate change problem.

The less than impressive levels of leadership recognition also suggest that none of the main leadership contenders currently enjoy the credibility so crucial for any actor that aspires to be an effective leader. The fact that the main contenders to exercise international climate change leadership are struggling to be recognized as leaders is likely to hamper the effectiveness of the climate change regime, particularly with regards to reaching widespread agreement on new measures that will be needed to reduce GHG emissions to levels that the scientific consensus says is needed to avoid dangerous climate change.

Our research clearly shows that there are no short cuts available for actors aspiring to be leaders. The only way to strengthen the legitimacy of international climate change leadership is for the main leadership contenders to convince others that they are truly committed to tackling the climate change problem. This work needs to start at home with meaningful domestic action, but it will also require the Big Three to constructively cooperate together and with others at the global level. The improved working relationships between the EU, the US and China visible at COP-16 in Cancún could represent the first step towards strengthening the legitimacy of international climate change leadership. COP-17 in Durban provides an opportunity for the EU, the US and China to provide the leadership that will be needed to successfully implement and build on the agreements reached in Copenhagen and Cancún (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

There is a strong need for a climate change leadership that is devoted to meaningful action. Photo by Helena Davidsson

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the support for this research from Mistra—the Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research, through the Climate Policy Research Program, Clipore.

Biographies

Christer Karlsson

is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, Uppsala University in Sweden. He has been involved in the research program Clipore (Climate Policy Research) funded by Mistra (The Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research). He has published books, articles and book chapters in his principal research areas: climate change politics, European Union studies and democratic theory. His recent publications have been published in journals such as Ambio, European Law Journal, Global Environmental Politics, and Journal of Common Market Studies.

Mattias Hjerpe

holds a PhD in Water and Environmental Studies and is Assistant Professor at the Centre for Climate Science and Policy Research at Linköping University, Sweden. He has been involved in the research program Clipore (Climate Policy Research) funded by Mistra (The Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research). His current research focuses on civil society actors’ role in climate change governance and how local government and civil society actors respond to global environmental and economic change. His recent work has been published in journals such as Climate Policy, Local Environment and Futures.

Charles F. Parker

is Associate Professor of Political Science at the Department of Government, at Uppsala University in Sweden. He has been involved in the research program Clipore (Climate Policy Research) funded by Mistra (The Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research). His research has focused on international and EU climate change politics, the impact of international institutions, and the origins and consequences of the warning-response problem. His recent publications have been published in journals such as Ambio, Global Environmental Politics, Journal of Common Market Studies, Political Psychology, Foreign Policy Analysis, Cooperation and Conflict and Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management.

Björn-Ola Linnér

is Professor in Water and Environmental Studies and director of the Centre for Climate Science and Policy Research at Linköping University, Sweden. He has been involved in the research program Clipore (Climate Policy Research) funded by Mistra (The Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research). Recent publications include analyses of linkages between climate policy and sustainable development, transnational governance, and North–South relations in international climate cooperation. He has published The Return of Malthus: Environmentalism and Post war Population-Resource Crises (2003), amongst others.

Contributor Information

Christer Karlsson, Email: Christer.Karlsson@statsvet.uu.se.

Mattias Hjerpe, Email: mattias.hjerpe@liu.se.

Charles Parker, Email: Charles.Parker@statsvet.uu.se.

Björn-Ola Linnér, Email: bjorn-ola.linner@liu.se.

References

- AFP. 2009. Obama pledges US lead on climate change. http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5i-sLNr8cB0J-fjcMJZnzcrE-X5yw. Accessed 5 Apr 2009.

- Bodansky D. The legitimacy of international governance: A coming challenge for international environmental law? The American Journal of International Law. 1999;93:596–624. doi: 10.2307/2555262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan A, Keohane RO. The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics and International Affairs. 2006;20:405–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7093.2006.00043.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carin B, Mehlenbacher A. Constituting global leadership: Which countries need to be around the summit table for climate change and energy security? Global Governance. 2010;16:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Christoff P. Cold climate in Copenhagen: China and the United States at COP15. Environmental Politics. 2010;19:637–656. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2010.489718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. 2007. Presidency Conclusions. Brussels, 9 March.

- Elgström O. The European Union as a leader in international multilateral negotiations—a problematic aspiration? International Relations. 2007;21:445–458. doi: 10.1177/0047117807083071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groenleer MLP, Schaik LG. United we stand? The European Union’s international actorness in the cases of the international criminal court and the Kyoto protocol. Journal of Common Market Studies. 2007;45:969–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00756.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Ringius L. The EU’s climate leadership: Reconciling ambition and reality. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics. 2001;1:281–299. doi: 10.1023/A:1010185407521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Grijp N. Leadership in the climate change regime: The European Union in the looking glass. International Journal of Sustainable Development. 1999;2:303–322. doi: 10.1504/IJSD.1999.004323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Grijp N. Perceptions of the EU’s role. In: Gupta J, Grubb M, editors. Climate change and European leadership: A sustainable role for Europe? Dordrecht: Kluwer Academich Publishers; 2000. pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson C. Democracy, legitimacy and the European Union. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson C, Parker C, Hjerpe M, Linnér B. Looking for leaders: Perceptions of climate change leadership among climate change negotiation participants. Global Environmental Politics. 2011;14:89–107. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian B, Elgström O. Still a green leader: The European Union’s role in international climate negotiations. Cooperation and Conflict. 2010;45:255–273. doi: 10.1177/0010836710377392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malnes R. “Leader” and “Entrepreneur” in international negotiations: A conceptual analysis. European Journal of International Relations. 1995;1:87–112. doi: 10.1177/1354066195001001005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RB. International politics and the environment. London: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nye JS. The future of American power. Foreign Affairs. 2010;89:2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Parker C, Karlsson C. Climate change and the European Union’s leadership moment: An inconvenient truth? Journal of Common Market Studies. 2010;48:923–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02080.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ringius L. Differentiation, leaders and fairness: Negotiating climate commitments in the European community. International Negotiation. 1999;4:133–166. doi: 10.1163/15718069920848435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schirm SA. Leaders in need of followers: Emerging powers in global governance. European Journal of International Relations. 2009;16:197–221. doi: 10.1177/1354066109342922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs M, Tiberghien Y. Multi-level reinforcement: Explaining European Union leadership in climate change mitigation. Global Environmental Politics. 2007;7:19–46. doi: 10.1162/glep.2007.7.4.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöstedt, G. 1994. Negotiating the Uruguay round of the general agreement on tariffs and trade. In International multilateral negotiation: Approaches to the management of complexity, ed. W.I. Zartman, 44–69. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass Publishers.

- Tallberg J. Leadership and negotiation in the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Underdal, A. 1994. Leadership theory: Rediscovering the arts of management. In International multilateral negotiation: Approaches to the management of complexity, ed. W.I. Zartman, 178–197. San Francisco: Jossey–Bass Publishers.

- Vogler J. The European contribution to global environmental governance. International Affairs. 2005;81:835–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00487.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler J. Climate change and EU foreign policy: The negotiation of burden sharing. International Politics. 2009;46:469–490. doi: 10.1057/ip.2009.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler JHH. The transformation of Europe. Yale Law Journal. 1991;100:2405–2483. doi: 10.2307/796898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young O. Political leadership and regime formation: On the development of institutions in international society. International Organization. 1991;45:281–309. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300033117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]