Abstract

A convergent synthesis of the marine natural product (+)-peloruside has been reported. This target has been assembled through the successive application of two methyl ketone boron aldol addition reactions to the latent C7–C11 dialdehyde synthon. This approach afforded a 22-step synthesis of this natural product. The influence of resident stereocenters on aldol reaction diastereoselection has been examined in detail.

Peloruside A (1) is a secondary metabolite of a marine sponge (Mycale genus) collected from Pelorus Sound, New Zealand. In addition to its structure elucidation, the initial disclosure by Northcote1 also demonstrated peloruside A to be cytotoxic to P388 murine leukemia cells at nanomolar concentrations. Subsequent investigations2 revealed peloruside’s anti-proliferation potency is similar to that exhibited by paclitaxel. The first synthesis of 1, reported by De Brabander, established the absolute stereochemistry of this natural product.3 In the interim, two additional syntheses have been published.4,5 The purpose of this communication is to report a convergent approach to this natural product suitable for analogue synthesis.

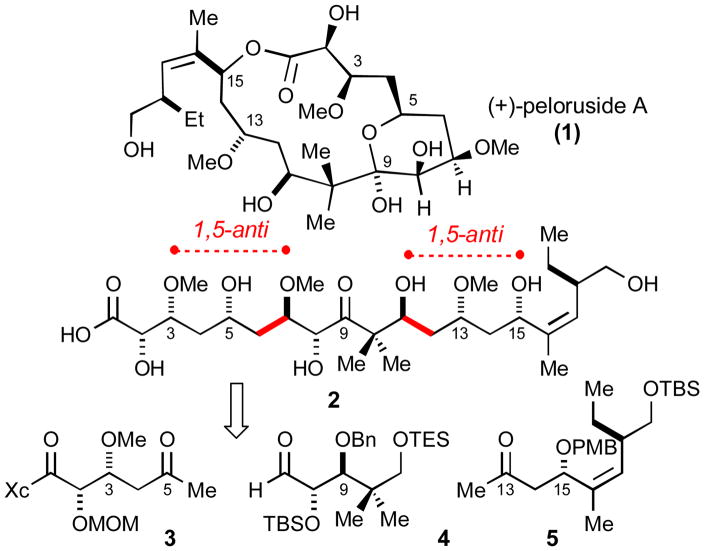

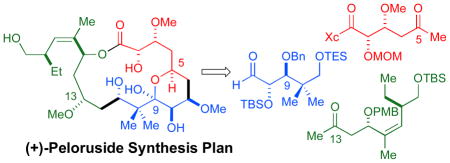

The deconstruction of 1 relies on the two highlighted aldol disconnections illustrated in Scheme 1. Based on prior art,6 we anticipated that the C3 and C15 stereocenters would favorably influence the stereochemical outcome of these two bond constructions. In the following discussion, the syntheses of subunits 3 and 4 will be described along with their elaboration to (+)-peloruside A (1). The synthesis of 5 is included in the Supplementary Information.

Scheme 1.

(+)-Peloruside A Synthesis Plan

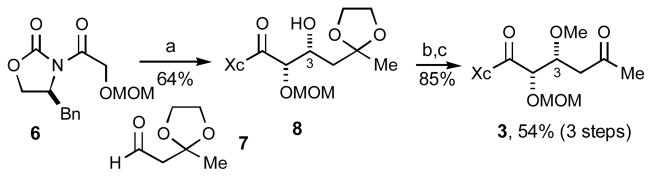

The synthesis of C1–C6 synthon 3 requires six steps from commercially available (S)-4-benzyl-2-oxazolidinone7a and is summarized in Scheme 2. Notably, the illustrated imide-based aldol bond construction establishes the C2–C3 syn stereochemistry with excellent diastereselection.7b

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the C1ŠC6 Synthon 3

a) 7, Bu2BOTf, i-Pr2EtN. b) Me3OBF4, proton sponge. c) PPTS, acetone, Δ.

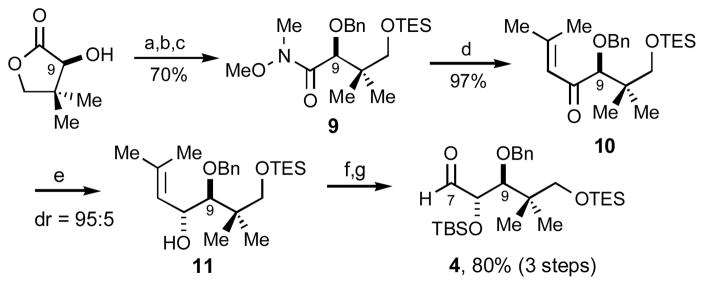

The synthesis of synthon 4, based on the use of (S)-pantolactone, is summarized in Scheme 3. The chelate-controlled borohydride reduction was quite diastereoselective (95:5); however, competing conjugate reduction was noted as a minor side reaction.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of the C7ŠC11 Synthon 4

a), BnON(H)CCl3, TfOH, rt. b) Me3Al, MeON(H)MeįHCl, CH2Cl2, 0 C. c) TESCl, Et3N, DMAP rt. d) Me2C=CHBr, t-BuLi, Et2O. e) Zn(BH4)2, Š30 C. f) TBSCl. g), O3, PPh3.

Selection of the illustrated C9 hydroxyl configuration in subunit 4 bears comment. On the basis of previous model studies probing the influence of β-oxygen stereocenters on aldehyde face selectivity,8 we concluded that the (R)-C3, (S)-C8 and (R)-C9 stereocenters in fragments 3 and 4 would be mutually reinforcing in this double stereodifferentiating aldol addition. A recent study by Paterson documents the diminished selectivities if the other C9 epimer is employed in a similar aldol addition.9

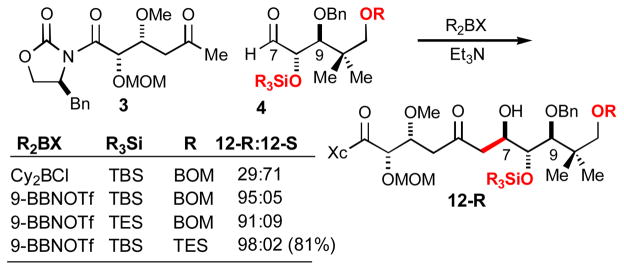

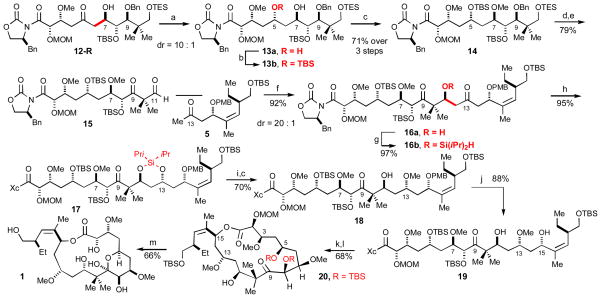

The aldol union of methyl ketone 3 and aldehyde 4 is summarized in Scheme 4. In developing this reaction, we noted a surprising diastereoselectivity dependence on the particular dialkylboryl enolate employed in the reaction. The desired diastereomer 12-R was obtained in 81% with 9-BBNOTf (Et3N, toluene).

Scheme 4.

The C6ŠC7 Aldol Bond Construction

Further complexity in this reaction is apparent by varying the C8 hydroxyl protecting group: when C8 bears a smaller protecting group (TES) a diminished diastereoselection (10:1) is observed.10 Finally, the structure of the C11 hydroxyl protecting group was also found to play a role in reaction diastereoselectivity.

The advanced stages of the synthesis are illustrated in Scheme 5. The triacetoxyborohydride reduction of 12-R proceeded with the expected 1,3-anti diastereoselectivity (10:1).11 A selective silylation of the less hindered C5 hydroxyl group of diol 13a delivered 13b.

Scheme 5.

Completion of (+)-Peloruside A Synthesis

a) Me4N(OAc)3BH, AcOH, MeCN, Š30 C. b) TBSCl, imidazole, rt. c) Me3OBF4, Proton SpongeØ, CH2Cl2, rt. d) Pd(OH)2/C, H2, EtOAc, rt. e) Dess-Martin, pyridine, CH2Cl2, 0 C. f) 9-BBNOTf, DIPEA, g) (iPr)2SiHCl, DMAP, DMF. h) SnCl4, Š78 C. i) 1:1 TBAF, HOAc, THF, Š20 C. j) DDQ. k) H2O2, LiOH. l) C6H2Cl3COCl, DIPEA, THF, rt, then DMAP, toluene, 60°C. m) 1:1 4 N HCl, MeOH, 1 h, 0 C, 2 h at rt.

The aldol union of aldehyde 15 and methyl ketone 5 deserves special mention. As illustrated, this reaction proceeds in good yield and diastereoselectivity (92%, dr=20:1); nevertheless, the success of this reaction critically depends on the nature of the C9 substituent. For example, the reaction does not proceed if the C9 carbonyl is reduced and protected. We surmise that it is a simple case of enhanced aldehyde reactivity in 15 due to both reduced steric and enhanced electronic effects.

The chemo- and stereoselective triacetoxyborohydride reduction11 of diketone 16a also raises an interesting challenge. While we anticipated that steric effects would favor a selective anti reduction of the C13 carbonyl, we noted that virtually no C13/C9 selectivity was obtained for this transformation. A solution to this problem was found in the intramolecular silane reductions reported by Davis.12 Accordingly, silane 16b was prepared in anticipation of an intramolecular hydride reduction. The subsequent SnCl4 promoted intramolecular anti reduction proceeded in the desired sense with 40:1 selectivity (85%). The removal of the C11–C13 disilyloxane protecting group in 17 was followed by a C13–selective methylation of the derived diol to afford 18. Again, steric effects formed the basis for differentiation of the C11–C13 diol.

In the experiments leading up to the macrocyclization, we anticipated that we might selectively cyclize the diol 19 at C15 since the C11 hydroxyl reactivity was estimated to be lower relative to the C15 hydroxyl group by a comparison of their local steric environments. Toward this end, hydrolysis and subsequent Yamaguchi macrocyclization13 of diol 19 proceeded in 66% overall yield to afford the protected peloruside skeleton 20. It should be noted that the smaller macrolactone corresponding to cyclization of the C11 hydroxyl group was not observed. Subsequent deprotection afforded (+)-peloruside-A whose spectroscopic properties matched that of the natural product.

In conclusion, the synthesis of (+)-peloruside A has been accomplished in 22 steps (longest linear sequence) from commercially available (S)-pantolactone. The two pivotal aldol additions provide a straightforward approach to the convergent synthesis of the peloruside A skeleton. Upcoming objectives will focus on analogue synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support has been provided by the NSF (CHE-0608664) and NIH (5R01-GM081546-01). Support from Merck, Amgen, NSERC of Canada (A. W. H. S.), and the E. Schering Foundation are also gratefully acknowledged. We thank Professor De Brabander for a sample of (−)-1.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details and analytical data including copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds (xx pages) (PDF). The synthesis of methyl ketone 5 is also included. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.West LM, Northcote PT. J Org Chem. 2000;65:445–449. doi: 10.1021/jo991296y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hood KA, West LM, Rouwé B, Northcote PT, Berridge MV, Wakefield StJ, Miller JH. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3356–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao X, Wu Y, De Brabander J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:1648–1652. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Taylor RE, Jin M. Org Lett. 2005;7:1303–1305. doi: 10.1021/ol050070g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Taylor RE, Jin M. Org Lett. 2003;5:4959–4961. doi: 10.1021/ol0358814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh AK, Xu X, Kim JH, Xu CX. Org Lett. 2008;10:1001–1004. doi: 10.1021/ol703091b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Paterson I, Gibson KR, Oballa RM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8585–8588. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA, Coleman PJ, Côte B. J Org Chem. 1997;62:788–789. [Google Scholar]; (c) Evans DA, Cote B, Coleman PJ, Connell BT. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10893–10898. doi: 10.1021/ja027640h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Gage JR, Evans DA. Org Synth. 1989;68:77–82. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA, Bartroli J, Shih TL. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2127–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans DA, Cee VJ, Siska J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9433–9441. doi: 10.1021/ja061010o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paterson I, Di Francesco ME, Kuhn T. Org Lett. 2003;5:599–602. doi: 10.1021/ol034035q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For an allylation-based approach to the C1–C11 fragment: Owen RM, Roush WR. Org Lett. 2005;7:3941–3944. doi: 10.1021/ol0514303.

- 11.Evans DA, Chapman KT, Carreira EM. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;10:3560–3578. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anwar S, Davis AP. Tetrahedron. 1988;44:3761–3770. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inanaga J, Hirata K, Saeki H, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1979;52:1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.