Abstract

Mutations in TARDBP, encoding TAR DNA-binding protein-43 (TDP-43), are associated with TDP-43 proteinopathies, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). We compared wild-type TDP-43 and an ALS-associated mutant TDP-43 in vitro and in vivo. The A315T mutant enhances neurotoxicity and the formation of aberrant TDP-43 species, including protease-resistant fragments. The C terminus of TDP-43 shows sequence similarity to prion proteins. Synthetic peptides flanking residue 315 form amyloid fibrils in vitro and cause neuronal death in primary cultures. These data provide evidence for biochemical similarities between TDP-43 and prion proteins, raising the possibility that TDP-43 derivatives may cause spreading of the disease phenotype among neighboring neurons. Our work also suggests that decreasing the abundance of neurotoxic TDP-43 species, enhancing degradation or clearance of such TDP-43 derivatives and blocking the spread of the disease phenotype may have therapeutic potential for TDP-43 proteinopathies.

FTLD is a common form of dementia, second in incidence only to Alzheimer’s disease among individuals with early onset dementia1. Pathologically, individuals with FTLD show atrophy often limited to the prefrontal and anterior temporal lobes, although clinically they may display significant heterogeneity. FTLD can be classified into distinct groups on the basis of immunohistochemistry, as either tauopathy with tau-positive inclusions (FTLD-tau) or ubiquitinopathy with tau-negative but ubiquitin-positive (ub+) neuronal inclusions (FTLD-U; ref. 2 and references within). Recent studies show that most ub+ inclusions contain TDP-43 (refs. 3,4), and most of the remainder contain fused in sarcoma/translocated in liposarcoma (FUS/TLS)5,6. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS are both DNA- and RNA-binding proteins involved in numerous aspects of gene regulation. Collectively, neurodegenerative diseases with TDP-43–immunoreactive pathology have been named TDP-43 proteinopathies7.

Encoded by the TARDBP gene, TDP-43 is a multifunctional DNA- and RNA-binding protein that is involved in many cellular processes, including RNA transcription, alternative splicing and mRNA stability regulation8–10. Since the landmark discovery of TDP-43 as an important component of inclusion bodies in ALS and FTLD, more than 30 TDP-43 mutations have been identified in individuals affected by ALS and FTLD with TDP-43–immunoreactive pathology (FTLD-TDP)9. The C-terminal fragments of human TDP-43 (hTDP-43) are detected in tissue samples from individuals with ALS and FTLD-TDP3,4,11–13, suggesting that the C-terminal domain may have a role in TDP-43 proteinopathy.

Transient expression of the mutant hTDP-43 gene leads to apoptotic death of spinal motor neurons in chicken embryos14. Overexpression of wild-type or mutant hTDP-43 causes motor neuron degeneration in mice and rats15–18. Our previous studies show that simply overexpressing the wild-type human TDP-43 in cultured cells or in transgenic flies is sufficient to cause pathology mimicking that found in individuals with TDP-43 proteinopathy19,20. However, molecular mechanisms by which TDP-43 mutations lead to neurotoxicity remain to be elucidated. Here we examined wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43 both in cultured cells and in the Drosophila melanogaster model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Synthetic TDP-43 peptides flanking amino acid residue 315 form amyloid fibrils in vitro and cause neuronal death with axonal damage when added to cultured neurons. Our work identifies an amyloidogenic and neurotoxic region in the C-terminal domain of TDP-43, flanking residue 315. These experiments reveal previously unknown similarities between TDP-43 and prion proteins in their peptide sequences and biochemical properties.

RESULTS

Neurotoxicity and motor neuron deficits with mutant TDP-43

To understand how mutations in the TDP-43 gene cause neurodegeneration, we generated transgenic flies expressing human TDP-43 (hTDP-43) containing the ALS-associated mutation A315T. We chose two wild-type lines and three A315T mutant lines that showed similar expression of hTDP-43 for further characterization (Supplementary Fig. 1). Use of strong promoters such as the actin-Gal4 driver caused death of flies expressing mutant TDP-43 during the embryonic stages. When we used the OK371-Gal4 driver to drive specific expression of the mutant hTDP-43 in subsets of motor neurons, we noticed that flies often failed to eclose and that surviving flies were smaller than flies expressing either the vector control or wild-type hTDP-43 (Fig. 1a–c; compare right panels showing larvae).

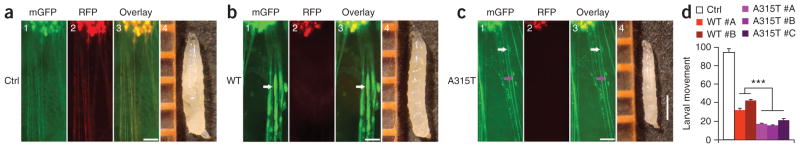

Figure 1.

Expression of A315T mutant hTDP-43 in motor neurons (MNs) leads to enhanced axonal damage and more severe impairment of locomotive function. (a–c) MNs expressing either wild-type hTDP-43 (WT; b) or the A315T mutant (c) showed marked axon swelling (indicated by arrows) and disruption of axonal integrity, whereas MNs in vector control flies (a) showed normal axonal morphology. Fluorescence microscopic images are shown, including membrane GFP (mGFP, green; panel 1), RFP signal (red; panel 2) and overlay of images in different channels (panel 3) (scale bars, 50 μm). Axon swelling is marked by white arrows, whereas a loss of axonal integrity is marked by the purple arrow. Images of the third-instar larvae of corresponding groups are shown in panel 4, with rulers in orange (scale bar, 1 mm). (d) Flies expressing hTDP-43 in MNs show functional deficits. Two and three independent lines of flies expressing WT TDP-43 or the A315T mutant, respectively, were scored and compared with the vector control group (n = 20 in each group). Data were compared using one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni post hoc test. A315T mutant flies showed more severe movement deficits. ***P < 0.001. Fly genotypes: control, OK371-Gal4/UAS-mGFP/UAS-RFP; WT, OK371-Gal4/UAS-mGFP/UAS-Wt-hTDP43-RFP; A315T, OK371-Gal4/UAS-mGFP/UAS-A315T-hTDP43-RFP.

Expression of membrane-bound green fluorescent protein (mGFP) in these flies allowed us to examine their motor neurons via their mGFP-marked axons. As compared to the control group, flies expressing either wild-type or A315T mutant TDP-43 showed axonal abnormalities (Fig. 1). Motor neurons expressing wild-type or mutant TDP-43 showed axonal swelling (Fig. 1b,c, white arrows). In the A315T mutant group, flies frequently died before the third instar stage. All of the larvae expressing A315T mutant TDP-43 that survived to the third instar stage showed a marked axonal loss (Fig. 1c). In the remaining axons we detected severe damage, including axon swelling (white arrows), axon thinning and defects in axonal integrity (purple arrows). We examined larval movement in different lines of transgenic flies with consistent results. Both the wild-type and A315T mutant groups showed substantial movement impairment as compared with the control flies expressing the red fluorescent protein (RFP) vector. Flies expressing the A315T mutant hTDP-43 showed more severe movement deficits than did flies expressing wild-type hTDP-43 (Fig. 1d), although expression of hTDP-43 in the wild-type and A315T groups was comparable (Supplementary Fig. 1).

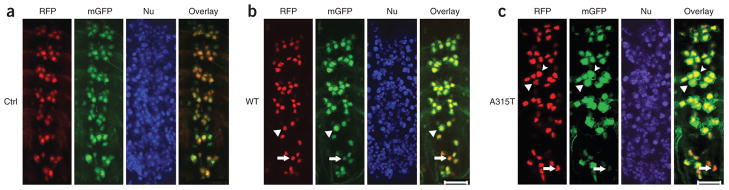

Motor neurons in the control RFP vector–expressing flies showed well-organized clusters in the ventral nerve cord (Fig. 2a), whereas motor neurons in larvae expressing wild-type or mutant hTDP-43 showed disorganized motor neuron clusters and neuronal loss, especially in the posterior abdominal segments (Fig. 2b,c). By the third instar stage, condensed nuclei appeared in motor neurons in the posterior abdominal segments, consistent with our previous study20. Quantification of motor neurons in the last three abdominal segments showed that ~79% of neurons expressing A315T mutant TDP-43 showed signs of cell body swelling or nuclear condensation (marked by the arrowhead and arrow, respectively), as compared to about 32% in flies expressing wild-type TDP-43 (Fig. 2b,c). Flies expressing the A315T mutant had more severe motor neuron loss and axonal damage, accompanied by more severe movement deficits, than did the wild-type hTDP-43 group (Figs. 1 and 2). We noticed that the motor neuron damage in these transgenic flies often occurred in a group fashion with clustered cell loss or axonal loss.

Figure 2.

Expression of the A315T mutant causes more severe motor neuron (MN) damage. (a) Control flies have normal MNs with well-organized clusters in the ventral nerve cord (VNC). mGFP, membrane GFP; red fluorescent protein, RFP; Nu, Hoechst dye nuclear staining. (b,c) MNs in third-instar larvae of transgenic flies expressing hTDP-43 show cell death and morphological abnormality in MN clusters, especially in the last three VNC segments. MN damage is much more prominent in flies expressing the A315T mutant. Arrowheads mark swollen neurons with the mGFP area enlarged. Arrows mark MNs with fragmented or condensed nuclei and reduced mGFP signals. Quantification of MNs in the last three VNC segments indicates that 79 ± 5% of MNs expressing the A315T mutant, as compared to 32 ± 3% of those expressing wild-(WT) type TDP, show cell body swelling or condensed nuclei (with six flies in each group scored in three independent experiments). Fly genotypes: a, OK371-Gal4/UAS-mGFP/UAS-RFP; b, OK371-Gal4/UAS-mGFP/UAS-TDP-43-RFP; c, OK371-Gal4/UAS-mGFP/UAS-A315T TDP-43-RFP. Scale bars, 20 μm.

We also tested effects of A315T mutant TDP-43 expression in mammalian cells. When expressed in cultured neurons, the A315T mutant formed cytoplasmic protein aggregates. Neurons expressing A315T mutant TDP-43 showed substantially lower survival than those expressing wild-type TDP-43 protein (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, expression of the ALS mutant A315T TDP-43 in both cultured mammalian neurons and fly motor neurons in vivo leads to significantly increased neurotoxicity as compared to wild-type TDP-43.

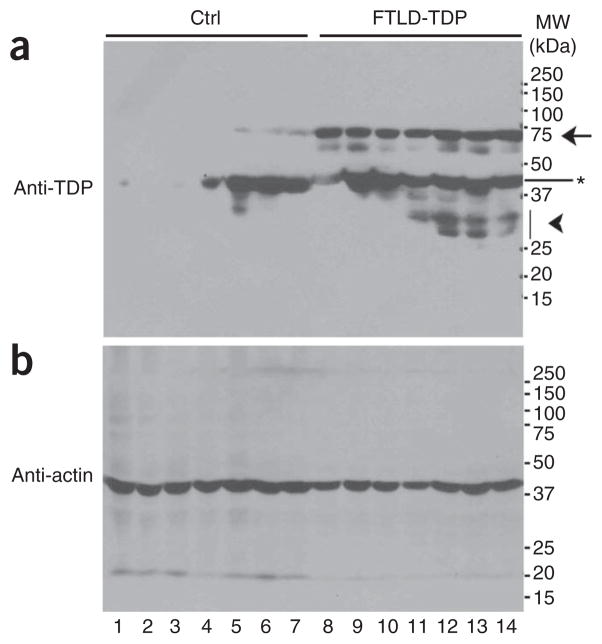

Detection of TDP-43 protein species in FTLD-TDP samples

We examined postmortem brain tissues from the brain bank of the Cognitive Neurology & Alzheimer’s Disease Center (CNADC) at Northwestern University. Seven control samples from subjects without clinical cognitive impairment or obvious TDP-43–positive pathology (control group) and seven FTLD-U samples with TDP-43–immunoreactive inclusions (FTLD-TDP) were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer and analyzed by western blotting using a polyclonal antibody specific for TDP-43. As expected, the control brain samples showed moderate levels of TDP-43 (migrating at the expected molecular weight of 43 kDa), which were detectable in four of the seven control brain samples on western blots after long exposures (Fig. 3a). In contrast, FTLD-TDP brain samples showed substantially higher total amounts of different TDP-43 species, although input protein quantities were similar, as shown by western blotting using anti-actin antibody (Fig. 3a,b). In addition to the predicted 43-kDa band and lower-molecular-weight species (marked by ★ and the arrowhead, respectively), we detected an abnormal species migrating around 74 kDa in all seven subjects with FTLD-TDP. We observed this 74-kDa species only at low level, after a long exposure of the western blot, in three of the seven control brain samples (marked by the arrow). This suggests that the 74-kDa TDP-43 derivative may represent a common aberrant TDP-43 product associated with FTLD-TDP.

Figure 3.

FTLD-TDP brain samples show abnormal TDP-43–immunoreactive species. (a) RIPA-soluble protein lysates were prepared from postmortem brain tissues from seven control subjects and seven subjects with TDP-43–immunoreactive FTLD (see Online Methods and Supplementary Methods). Control samples were from non–cognitively impaired subjects with minimal Alzheimer’s disease pathology containing Braak & Braak tangle stages II–III, except for one with mild cognitive impairment and pathological diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease (lane 7). The samples were analyzed by western blotting using specific anti–TDP-43 antibodies. Several TDP-43–positive bands were detected, including the predicted band migrating at 43 kDa (*), bands migrating at ~74 kDa (arrow) and a band migrating faster than 37 kDa (arrowhead). The 74-kDa species was prominent in samples from seven of the subjects with FTLD-TDP (lanes 8–14) but was detectable at only a low level in samples from three (lanes 5–7) out of seven of the control subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (lanes 1–7). (b) Actin was used as a control showing that similar amounts of total proteins were loaded.

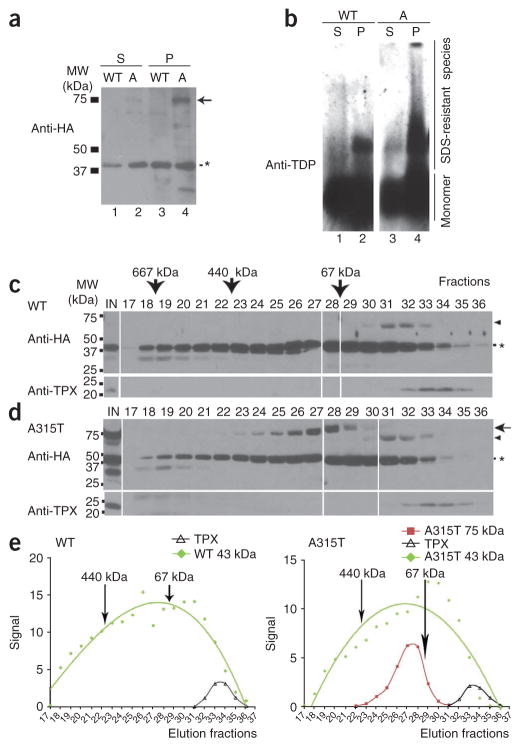

A315T forms protein aggregates and aberrant TDP-43 species

We next tested whether a similar aberrant TDP-43 protein species was produced in TDP-43–expressing cells. We prepared stable HEK293 cell lines expressing either wild-type or A315T mutant TDP-43 as hemagglutinin (HA) epitope–tagged proteins. These stable cell lines were used for biochemical experiments. We then separated protein lysates from TDP-43–expressing cells into Sarkosyl-soluble and Sarkosyl-insoluble pellet fractions (Supplementary Methods), then analyzed them by SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions. Western blotting using a specific antibody against the HA tag revealed a band migrating at around 75 kDa, detectable only in cells expressing the A315T mutant TDP-43 but not those expressing wild-type TDP-43 (Fig. 4a, marked by the arrow). The 75-kDa band was much more abundant in the Sarkosyl-insoluble fraction (Fig. 4a; compare lane 2 with lane 4).

Figure 4.

Biochemical characterization of TDP-43–immunoreactive species. (a) Stable HEK293 cells expressing HA-tagged wild-type or A315T hTDP-43 were lysed in RIPA buffer. The RIPA-insoluble fraction was extracted in RIPA buffer containing 2% (w/v) Sarkosyl and 500 mM NaCl. Sarkosyl-soluble (S) and Sarkosyl-insoluble pellet (P) fractions were separated by centrifugation and analyzed by western blotting using anti-HA. In addition to the expected 43-kDa band (*), a prominent band migrating at approximately 75 kDa was detected in the Sarkosyl-insoluble pellet from cells expressing A315T TDP-43 (lane 4). This 75-kDa was detected only at a low level in the Sarkosyl-soluble fraction (lane 2) and was not detectable in the cell lysates expressing wild-type TDP-43. (b) SDS-resistant aberrant TDP-43 species were detected in the Sarkosyl-insoluble pellet of lysates from cells expressing TDP-43. The Sarkosyl-soluble fractions (lanes 1 and 3) or Sarkosyl-insoluble pellets (lanes 2 and 4) from either the wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) or A315T mutant (lanes 3–4) TDP-43 cells were analyzed by semidenaturing agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE) as described47 followed by western blotting using a specific anti–TDP-43 antibody. Sarkosyl-insoluble fractions were extracted using 3% SDS buffer before being loaded on SDD-AGE. SDS-resistant oligomeric species (migrating slower than the monomer species) were substantially more abundant in cells expressing the A315T mutant than in those expressing the wild-type TDP-43. (c,d) RIPA-soluble fractions of cell lysates expressing either wild-type TDP-43-HA (c) or A315T TDP-43-HA (d) were loaded onto a gel filtration column with different fractions examined by western blotting using anti-HA or anti-TPX antibodies. IN, input cell lysates. The arrow and arrowheads mark the 75-kDa and 60-kDa high-molecular-weight species, respectively. The asterisk marks the expected 43-kDa monomer TDP-43 band. Some gel lanes have been omitted for reasons of space; the complete gel image is provided in Supplementary Figure 3. (e) Western blot signals in c and d were plotted for the 43-kDa species (green), 75-kDa species (red) of A315T TDP-43 and TPX band (black) for different fractions, with 440-kDa and 67-kDa size markers indicated. The 23-kDa TPX protein was detected in fractions 32–35. The aberrant 75-kDa A315T TDP-43 species was detected in fractions 24–29, corresponding to molecular weight range from 440 kDa to 67 kDa.

Following 3% SDS extraction of Sarkosyl-insoluble pellets, we analyzed Sarkosyl-soluble and Sarkosyl-insoluble fractions by electrophoresis under semidenaturing conditions21 (Fig. 4b). We detected an SDS-resistant TDP-43–immunoreactive oligomer species in cells expressing wild-type TDP-43 and those expressing the A315T mutant, with the SDS-resistant oligomeric species being much more abundant in Sarkosyl-insoluble fractions (compare lane 2 with lane 1 and lane 4 with lane 3; Fig. 4b). There was a substantially higher concentration of SDS-resistant TDP-43–positive oligomer species in the cells expressing the A315T mutant than in those expressing TDP-43 (compare lane 4 with lane 2; Fig. 4b).

We examined the biochemical behavior of TDP-43 protein species by size-exclusion chromatography using RIPA-soluble protein lysates prepared from HEK293 stable cells expressing either wild-type or A315T mutant TDP-43-HA proteins. Following gel filtration, we analyzed the different fractions by western blotting with anti-HA antibody. The 43-kDa TDP-43 protein was present in fractions ranging from >667 kDa to <23 kDa (Fig. 4c–e; Supplementary Figure 3), as marked by molecular size markers in conjunction with the 23-kDa cytosolic protein of thioredoxin peroxidase (TPX) family, a protein that interacts with presenilin22,23. In addition to the 43-kDa monomer species, we detected an aberrant 75-kDa TDP-43 species (marked by the arrow) lysates from cells expressing the A315T mutant TDP-43 in the high-molecular-weight fractions between the 440-kDa and 67-kDa molecular weight markers (fractions 24–29) (Fig. 4d,e). In contrast, we detected the 60-kDa TDP-43 species in lysates from cells expressing either wild-type TDP-43 or the A315T mutant almost exclusively in fractions 31–33 of gel filtration (marked by the arrowhead in Fig. 4c,d). These data suggest that, in solution, TDP-43 exists in multiple oligomeric conformations.

To test whether the aggregation tendency of TDP-43 was intrinsic to TDP-43 or dependent on the presence of other mammalian cellular proteins, we used recombinant TDP-43 protein purified from Escherichia coli. We purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged TDP-43 (either wild type or A315T) to more than 95% homogeneity and subjected it to gel filtration analyses (Supplementary Fig. 4). GST-tagged proteins were used because the TDP-43 protein became unstable when the GST tag was cleaved. We detected both the wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43 proteins predominantly as a 70-kDa band (the expected molecular weight of a monomeric GST–TDP-43 fusion protein) in a wide range of fractions between the 667-kDa and 13.7-kDa molecular weight markers. This suggests that the purified TDP-43 protein alone may form high-molecular-weight oligomers and/or adopt different conformations in solution. In addition, we detected a ladder of lower-molecular-weight species ranging from 65 kDa to 29 kDa by western blotting using anti–TDP-43 antibody in A315T TDP-43 fractions, suggesting that these TDP-43 species may be more resistant to degradation.

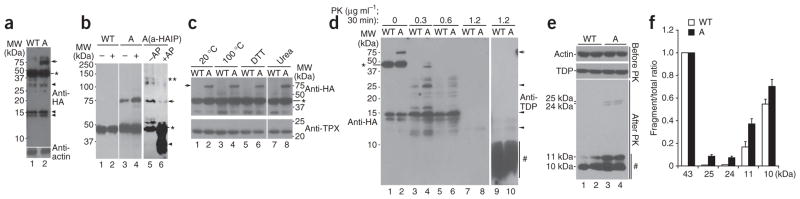

We further investigated aberrant TDP-43 species in mammalian cells. We prepared RIPA-soluble cell lysates from the wild-type TDP43-HA or A315T TDP-43-HA stable expression cells and separated them by SDS-PAGE. Western blotting analyses of these cell lysates with anti-HA antibody revealed 75-kDa (detected as 75–76 kDa doublets on some gels), 43-kDa and lower-molecular-weight bands (Fig. 5a). The 75-kDa species was detected at a substantially greater abundance in cell lysates expressing A315T mutant TDP-43 (Fig. 5a). This 75-kDa species was phosphorylated because treating cells with the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (OA) increased its concentration (Fig. 5b; compare lane 4 with lane 3). Conversely, alkaline phosphatase treatment substantially reduced the amount of the 75-kDa species, with a concomitant increase in the 43-kDa and lower-molecular-weight bands (Fig. 5b, compare lane 6 with lane 5). Consistent with this, the 75-kDa aberrant TDP-43 species was resistant to heating (up to 100 °C for 15 min), reducing conditions of 200 mM DTT and denaturation with 6 M urea, suggesting that the 75-kDa species is covalently modified (Fig. 5c). MS analysis confirmed that the purified 75-kDa band contained TDP-43 protein without detectable peptides of other proteins.

Figure 5.

Cells expressing A315T TDP-43 show high-molecular-weight phosphorylated protein species that are resistant to heat, DTT and urea and produce fragments partially resistant to protease K (PK) treatment. (a) High-molecular-weight bands are detected in lysates from cells expressing A315T TDP-43. Stable cells expressing HA-tagged wild-type or A315T TDP-43 (marked by WT or A, respectively) were lysed and subjected to western blotting using anti-HA antibody. In addition to the 43-kDa band (*), both higher-molecular-weight (75 kDa, arrows) and lower-molecular-weight bands (arrowheads) were detected. The 75-kDa species were resolved into 75–76-kDa doublets on some gels. (b) The abundance of the 75-kDa species (arrow) increased when lysates from cells expressing A315T TDP-43 were treated with okadaic acid (OA) and decreased when lysates were treated with alkaline phosphatase (AP). Cells expressing HA-tagged wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) or A315T mutant (lanes 3 and 4) TDP-43 were treated with the control vehicle or OA, and cell lysates were examined by western blotting using anti-HA antibody (lanes 1–4). Lanes 5 and 6 show western blots using anti–TDP-43 of reaction products treated with control or AP, after immunoprecipitation of cell lysates from cells expressing the A315T mutant using anti-HA (a-HA IP). The 43-kDa TDP-43 (*), higher-molecular-weight species (**) and lower-molecular-weight products (arrowhead) are also shown. (c) The 75-kDa species detected in cells expressing A315T TDP-43 was not affected by treatment with heat (20 °C, lane 2; 100 °C, lane 4), 200 mM DTT (lane 6) or 6 M urea (lane 8) in the presence of protease inhibitors. (d) Increased amounts of protease K–resistant TDP-43 derivatives were detected in cells expressing the A315T mutant TDP-43. Cell lysates from the wild-type or A315T TDP-43-HA cells were treated with protease K at different concentrations, separated on SDS-PAGE and western blotted using either anti-HA (lanes 1–8) or anti–TDP-43 (lanes 9 and 10) antibodies. Although the 75-kDa and 43-kDa TDP-43 species are sensitive to protease K treatment, a number of lower-molecular-weight bands, especially TDP-43–reactive species (5–10 kDa), are resistant to protease K (lanes 9–10). Representative bands partially resistant to protease K including 25–24 kDa, 15–14 kDa and 13–12 kDa are marked by arrowheads; a cluster of TDP-43 reactive bands ~5–10 kDa are marked by #. (e) Western blotting of cell lysates using anti-HA after treatment with protease K at 1 μg ml−1, with lanes 1 and 2, and lanes 3 and 4, containing duplicates of reactions. (f) Quantification of western blotting signals of protease K–resistant bands in e. Shown is the ratio of the corresponding band to the total amounts of signals including the full-length 43-kDa band, demonstrating that partially protease K–resistant bands (25–24 kDa or 11–10 kDa) were more abundant in cells expressing the A315T TDP-43 (black bars, A) than in those expressing wild-type TDP-43 (white bars, wild type). Error bars, s.e.m.

The above experiments suggest that the 75-kDa species is a hyperphosphorylated form of the TDP-43 protein. To test whether the 75-kDa species was also ubiquitinated, we immunoprecipitated the wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43-HA proteins using anti-HA monoclonal antibody, separated them by SDS-PAGE and blotted with a specific anti-ubiquitin antibody. Although the high-molecular-weight species (>100 kDa) were recognized by both anti–TDP-43 and anti-Ub, the 75-kDa species was not recognized by anti-Ub, supporting the idea that the 75-kDa species was not ubiquitinated (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Detection of protease-resistant species in TDP-43–expressing cells

We detected multiple lower-molecular-weight bands on western blots, including those migrating between 43 kDa (marked by ★) and 15 kDa (for example, those marked by double arrowheads in Fig. 5a), suggesting that some TDP-43 fragments or derivatives may be resistant to proteases present in the cell lysates. To test this, we carried out western blotting following digestion of cell lysates using different concentrations of protease K. Western blotting by anti-HA revealed ladders of TDP-43–reactive bands (Fig. 5d, lanes 1–6). After treatment with protease K at the concentration of 1.2 μg ml−1 for 30 min, we detected, using specific anti–TDP-43 antibodies, protease K–resistant TDP-43 species smaller than 10 kDa that were not reactive to anti-HA antibody (Fig. 5d, lanes 9–10 and lanes 7–8), indicating that the HA tag was cleaved off these TDP-43 fragments. Lysates from cells expressing A315T mutant TDP-43 showed consistently higher abundance of protease K–resistant species of different sizes (Fig. 5d; compare lanes 2, 4 and 6 with lanes 1, 3 and 5). Under similar conditions, even at the 0.3 μg ml−1 protease K concentration, none of the other proteins examined—including TPX, actin or GAPDH—showed any protease K–resistant bands. We quantified different protease K–resistant bands following protease K treatment at a moderate concentration (1 μg ml−1) and found that the A315T mutant consistently produced higher amounts of protease K–resistant fragments, including 24–25 kDa and 10–11 kDa, although we used the same amounts of input protein as detected by either anti-actin or anti–TDP-43 controls (Fig. 5e,f). These data indicate that TDP-43 is partially resistant to protease and that the A315T mutation further increases this protease resistance.

TDP-43 Ala315 flanking sequences resemble prion and form β-sheets

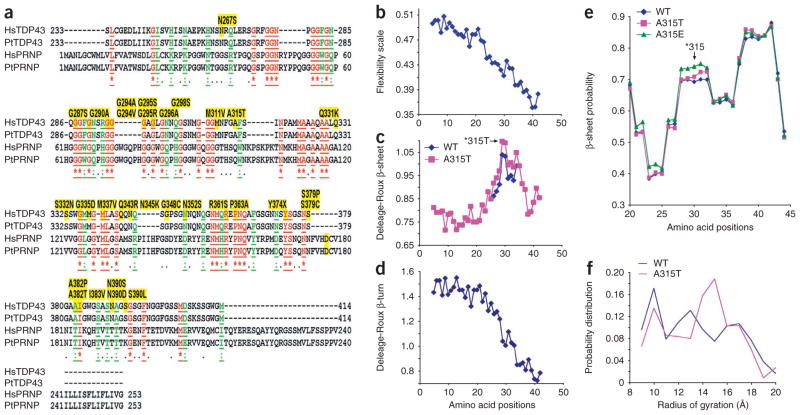

The above biochemical analyses show that the TDP-43 protein has the propensity to form high-molecular-weight aberrant species that are heat stable and detergent resistant. Moreover, the lower-molecular-weight TDP-43 fragments are partially resistant to protease K. These biochemical features are reminiscent of prion proteins. Consistent with this, our sequence analysis indicates that the C-terminal fragments of both human and chimpanzee TDP-43 have moderate sequence similarity to human and chimpanzee prion proteins (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Sequence features and structural prediction of the C-terminal fragments of TDP-43. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of TDP-43 synthetic peptides corresponding to residues 286–331 suggests that the A315T mutation increases the tendency of the protein to form β-sheet structures and to stay in extended conformation(s). (a) The alignment of peptide sequences of the C-terminal domain of TDP-43 (Ser233–Met414) with the prion proteins (PRNP) from Homo sapiens (Hs) and Pan troglodytes (Pt) reveals a moderate level of sequence similarity. The identical amino acid residues are in red and underlined; similar residues are in green and underlined. Proteinopathy-associated mutations of TDP-43 are shown as yellow highlighted residues above the corresponding region. (b–d) The peptide properties as predicted using the Protscale server of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB)24. The synthetic 46-mer peptides of either wild-type (blue) or the A315T mutant (pink) TDP-43 were analyzed for the flexibility scale, as described by Bhaskaran and Ponnuswamy25, and for predicted β-sheet and β-turn, using the Deleage-Roux scale26. The peptide profiles were smoothened using an equal-weight sliding window of nine amino acids. (e) The β-sheet probability of amino acid residues in TDP-43 peptides as further analyzed using a Ramachandran plot27. A residue is defined as having a β-sheet structure when −150 < φ < −60 and 100 < ϕ < 170 on the Ramachandran plot27. The probability of 1 means that the residue is 100% in β-sheet conformation during the course of MD simulation. The blue, pink and green lines represent statistics from simulations of the wild type, the A315T mutant and the A315E mutant, respectively. The 46-mer peptides were analyzed in their entirety; data are shown for amino acid positions 20–45, corresponding to amino acid 306–330 (note that amino acid position 30 corresponds to A315T in TDP-43 protein, as marked by ‘*315’ with an arrow). (f) The probability distribution of the radius of gyration of the TDP-43 peptides by MD simulation. The radius of gyration is defined as the root-mean-square distance of the collection of atoms from their common center of gravity. Radii of gyration in the range of 9–11 Å and 12–20 Å correspond to collapsed and extended conformations, respectively. The radii of gyration were calculated using the 46-mer peptide. The A315T mutant shows higher probability at 14–16 Å of radius of gyration, suggesting its higher tendency to stay extended.

Using a molecular dynamics simulation24, we analyzed different regions at the C-terminal domain of TDP-43. A 46-amino-acid fragment flanking residue 315, with either the wild-type alanine or mutant threonine at this position, showed notable features. For both the wild-type and the A315T mutant peptides, the N-terminal half of the 46-mer TDP-43–derived peptide seems to be more flexible, sampling multiple conformations, including a partially collapsed globular conformation. In contrast, the C-terminal half of the peptide probably adopts an extended β-sheet conformation.

The A315T mutant peptide shows a more extended conformation at its C terminus (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Movie 1). Consistent with this, analyses of the flexibility index, β-sheets and β-turns of the peptide sequence in this region of TDP-43 using the Protscale server (http://expasy.org/tools/protscale.html)24–26 revealed that the N-terminal half of the TDP-43 peptide seems to be more flexible and more prone to form β-turns than is the C-terminal half, whereas the C-terminal half (especially residues 313–321) has a higher propensity of forming β-sheets (Fig. 6b–d). This propensity to form β-sheets is further increased by the A315T mutation (Fig. 6c).

We also analyzed the TDP-43 peptides using a Ramachandran plot27. Again, the A315T mutation is predicted to increase the probability to form β-sheets (Fig. 6e) and has a higher probability of staying in an extended conformation at 14–16 Å of a radius of gyration (Fig. 6f). Notably, when we analyzed the TDP-43 peptide containing the A315E phosphomimetic mutant, the A315E mutant showed an even higher propensity to form β-sheets around the mutation site (Fig. 6e), supporting the idea that phosphorylation of this residue may affect the conformation of the TDP-43 protein.

TDP-43 peptides form amyloid fibrils

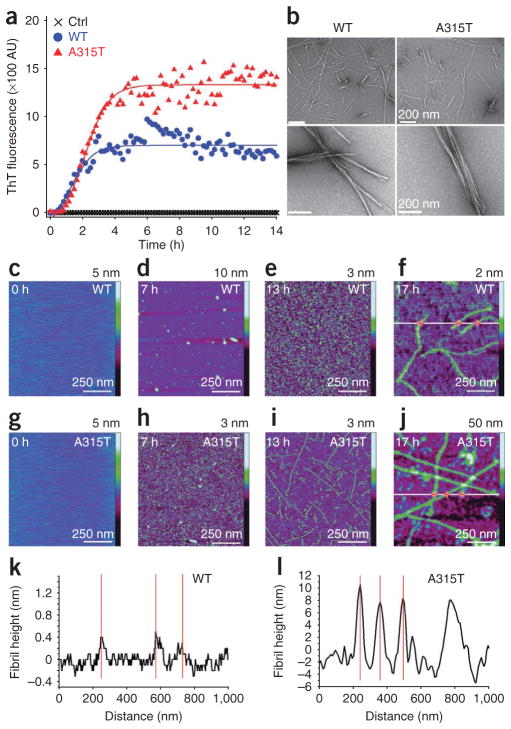

The prediction of β-sheet formation in these TDP-43 peptides led us to test whether such peptides could form amyloid fibrils. We prepared two TDP-43 peptides flanking amino acid residue 315, one with the wild-type sequence (wild-type TDP46mer: Gln286–Gln331) and the other with an identical TDP-43 peptide except that it contained phosphothreonine at residue 315 (A315T TDP46mer), together with a control peptide containing the reverse sequence of the amyloid peptide Aβ42. We tested these peptides for their interaction with thioflavin T (ThT). Binding of ThT to amyloid fibrils leads to increased fluorescence emission at 480 nm upon excitation at 440 nm28. Both the wild-type and A315T mutant synthetic 46-mer peptides showed significant fluorescence upon binding to ThT, whereas the control peptide had no detectable ThT fluorescence (Fig. 7a). Changes in ThT fluorescence intensity with time showed sigmoidal curves similar to those of other amyloid fibrils28,29 (Supplementary Methods).

Figure 7.

Synthetic TDP-43 peptides (wild-type or A315T mutant, Gln286–Gln331) form fibrils in vitro. (a) Time course of ThT binding of synthetic TDP-43 peptides. The wild-type (blue circles) or A315T mutant (red triangles) TDP-43 peptides or the control peptide (black crosses) is presented with dynamic changes in ThT binding at 37 °C. (b) EM images of fibrils formed with the wild-type or A315T TDP-43 peptides. Higher magnification is shown below. Scale bars, 200 nm. (c–j) Time-lapse AFM reveals dynamic process of protofibril and fibril formation of TDP-43 peptides. Time-lapse AFM images of wild-type TDP-43 (c–f) and A315T mutant TDP-43 synthetic peptide (g–j) during the formation of protofibrils and fibrils after incubation of peptides in aqueous solution at a concentration of 20 mM for 0, 7 h, 13 h and 17 h. All the images were obtained on a mica surface. (k,l) Corresponding cross-sectional profiles for the wild-type (f) and A315T mutant (j) TDP-43 peptides along the white lines, respectively. Z scale bars for the AFM images are as marked on the right. Red crosses in f and j mark the locations for the height measurements, which correspond to the red lines in k and l.

We carried out EM to examine the fibrils formed with the TDP-43 peptides. Consistent with their binding to ThT, both the wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43 synthetic peptides form fibril structures (Fig. 7b).

To examine the dynamic process of the fibril formation, we used time-lapse atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Fig. 7c–l). AFM images of the wild-type (Fig. 7c–f) or the A315T mutant peptide (Fig. 7g–j) aggregates formed on mica surface were taken following incubation times of 0, 7 h, 13 h and 17 h. We did not detect aggregates at the zero time point for either the wild-type or A315T mutant peptides (Fig. 7c,g). Aggregation of the wild-type TDP-43 peptide followed the process from initially granular oligomers, to mixtures of oligomers and short protofibrils, and finally thin fibrils (Fig. 7c–f). The A315T mutant peptide, however, showed a faster initial phase of protofibril formation, with numerous short thin protofibrils detectable by 7 h, thicker longer fibrils by 13 h, and finally long, thick fibers by 17 h of incubation (Fig. 7g–j). The corresponding cross-sectional profiles confirmed that the average height of the A315T mutant fibrils (7.7 nm) was larger than that of the wild-type fibrils (0.29 nm) (Fig. 7k,l).

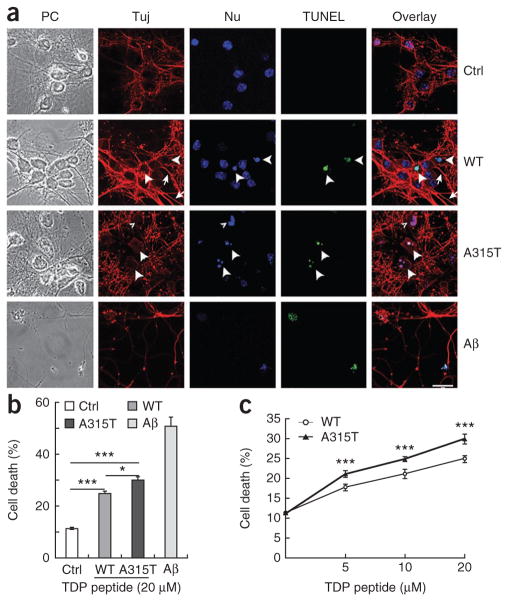

TDP-43 peptides cause neurotoxicity in primary neuronal cultures

We next examined whether these TDP-43–derived peptides affected neuronal survival when added to primary cultures. In addition to the TDP-43 synthetic peptides and the control peptide described above, we included the Aβ42 peptide as a positive control. After treating cultured primary mouse cortical neurons with corresponding peptides at different concentrations, we monitored neuronal death by immunostaining with the neuronal marker Tuj-1 antibody and nuclear staining with Hoechst dye 33342, followed by fluorescence microscopy. When neurons were treated with the control peptide, we detected only a baseline level of cell death. Consistent with previous studies30,31, treatment using Aβ42 peptide led to a marked increase in neuronal death (Aβ42 panels, Fig. 8). Treatment with the 46-mer wild-type peptide increased neuronal death, with cells showing positive terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining and the appearance of condensed or fragmented nuclei (as indicated by arrowheads in ‘TUNEL’ and ‘Nu’ panels, respectively). This was accompanied by increased axonal varicosity and reduced axonal integrity, with only a fraction of axons showing relatively normal morphology (marked by arrows in the Tuj-staining panels, Fig. 8a). Conversely, in A315T peptide–treated neurons, such neurotoxicity was further increased, with more than 30% of neurons showing TUNEL signals (Fig. 8b). Most axons in the A315T mutant peptide–treated group showed abnormal morphology, including increased varicosity and reduced axonal integrity (marked by arrowheads in the Tuj-staining panels, Fig. 8a). Neurotoxicity caused by these TDP-43 peptides was dose dependent (Fig. 8c). These data suggest that TDP-43 derivatives present in the extracellular environment cause significant neuronal damage.

Figure 8.

The A315T mutant synthetic TDP-43 peptide causes enhanced neurotoxicity as compared to the wild-type peptide in primary cortical neuronal cultures. (a) Fluorescence microscopic images of primary cortical neurons treated with the control peptide, wild-type TPD-43 peptide, phosphorylated A315T TDP-43 peptide or amyloid1–42 peptide (Ctrl, WT, A315T and Aβ42, respectively). Microscopic images corresponding to phase-contrast images (PC), Tuj1 immunostaining, Hoechst dye nuclear staining (Nu), TUNEL staining and the superimpositions of the corresponding groups of images are shown. The large arrowheads mark TUNEL-positive neurons undergoing cell death, whereas the small arrowhead in the A315T group marks an abnormal nucleus that is TUNEL negative. Neurites with normal morphology are marked by arrows. Most neurites in the A315T group were damaged, showing either abnormal varicosities or disruption of normal integrity. Scale bar, 20 μm. (b,c) Quantification of neuronal death as the percentage of TUNEL-positive neurons in the corresponding groups shown in a. The graph shows average values ± s.e.m. of data collected from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis in b was performed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test, and that in c with two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our results reveal molecular and biochemical features that are shared between TDP-43 and other amyloid proteins, including prions. Notably, the 46-mer TDP-43 peptide shows sequence similarity to the neurotoxic prion peptide PrP106–126 (Fig. 6)32. Our study thus identifies an amyloidogenic and neurotoxic region at the C-terminal domain of TDP-43. Our work also uncovers previously unrecognized similarities between TDP-43 and abnormal prion proteins, including partially protease-resistant protein fragments and amyloid fibril formation.

Cushman et al. recently proposed that the glycine-rich C-terminal domain (Gln277–Met414) of TDP-43 acts as a putative ‘prion domain’ with sequence similarity to yeast prion proteins33. This domain and additional sequences in the RNA-recognition motif were shown as the minimal region necessary to induce TDP-43 aggregation and toxicity when expressed in yeast or neuroblastoma cells34–36. Purified wild-type and ALS mutant TDP-43 proteins formed thread-like or filament-like non-amyloid structures37. Our study, in contrast, shows that synthetic peptide containing Q286-Q331 was sufficient not only to form amyloid fibrils but also to induce neurotoxicity. Additionally, A315T mutant phosphopeptide further increased the neurotoxicity (Fig. 8). This suggests that TDP-43 proteolytic peptides may cause neurotoxicity. Molecular modeling suggests that the C-terminal part of the TDP-43 peptide (Gln286–Gln331) adopts an extended β-sheet conformation. Mutating residue 315 from alanine to threonine further increases the β-sheet propensity and accelerates the formation of protofibrils (Figs. 6 and 7). This may help to explain why the A315T mutant peptide causes enhanced neurotoxicity.

It is interesting that, in human tissues, TDP-43 inclusions are not thioflavin S positive, whereas neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques are. This suggests that the conformation of TDP-43 inclusions is different from that of tangles and plaques. It is conceivable that β-sheets formed by TDP-43 peptide(s) may not be as extensive as in tangles and plaques. Alternatively, such TDP-43 β-sheets may be buried inside TDP-43 inclusions and therefore not accessible be for thioflavin S binding.

A previous report suggested that TDP-43 in yeast did not form SDS-resistant species34. Our analyses reveal a heat-stable 75-kDa TDP-43 species that is resistant to detergents, reducing agents and urea treatment, suggesting that the 75-kDa species is covalently modified, possibly by phosphorylation (Fig. 5). Consistent with this, we did not detect similar high-molecular-weight species with the A315T mutant TDP-43 protein purified from E. coli (Supplementary Fig. 4). The aberrant 75-kDa band in lysate from cells expressing the A315T mutant was not recognized by anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 5). The 75-kDa species in cells expressing the HA-tagged A315T mutant TDP-43 was protease sensitive, although multiple forms of lower-molecular-weight TDP-43 species, especially those 10 kDa, are protease resistant (Fig. 5d,e). It should be noted that TDP-43–immunoreactive species larger than 43 kDa have been detected in some samples from affected individuals4,38,39. In our experience, the 74-kDa TDP-43 species detected in such samples is unstable, possibly degraded by endogenous proteolytic enzymes. This may explain why this 74-kDa TDP-43 species in brain samples from affected individuals escaped notice in previous studies. The exact molecular nature of the 74-kDa TDP-43 species in brain samples and the 75-kDa aberrant species in cells expressing the HA-tagged A315T mutant TDP-43 remains to be elucidated.

In TDP-43 proteinopathy tissues, TDP-43 is often found cleared from the nuclei of neurons containing cytoplasmic inclusion bodies, suggesting that pathogenesis may be driven by a loss of normal TDP-43 function in the nucleus. We examined wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43 in a splicing assay using a previously reported cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) exon 9 minigene40. When co-transfected with the CFTR mini-gene, the C-terminal fragment T202 led to a substantial change in its ability to suppress exon 9 inclusion. In contrast, both wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43 proteins showed similar activity in suppressing exon 9 splicing (Supplementary Fig. 7). This suggests that the neurotoxic effect of the A315T mutant TDP-43 may not be caused by the loss of its splicing regulatory activity.

Several lines of evidence support the gain-of-function toxicity model. Most TDP-43 mutations identified are missense mutations. Deleting or knocking down expression of the TDP-43 homolog in flies20,41,42, or deleting the TARDBP gene in mice43, did not lead to the formation of inclusion bodies—characteristic neuropathological features of TDP-43 proteinopathy—although movement deficits and abnormal dendritic development were detected in TDP-43 deficient animals41–43. Simply overexpressing the wild-type TDP-43 is sufficient to induce protein aggregation in yeast or mammalian cells33,34,44,45 and leads to neurodegeneration with TDP-43 pathology in transgenic animals16,17,20,46. It is possible that both ‘loss of normal TDP-43 function’ and ‘gain-of-function toxicity’ mechanisms contribute to molecular pathogenesis in TDP-43 proteinopathy.

ONLINE METHODS

Plasmids, peptides and antibodies

Procedures for plasmids, peptides and antibodies are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Postmortem samples collection and analyses

Human brain samples were collected from autopsied tissues at the Neuropathology Core of the Northwestern University following US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and institutional guidelines. Brain samples were evaluated for atrophy, for pathology by hematoxylin-eosin staining and immunostaining using multiple antibodies. For details, see Supplementary Methods.

Primary neuronal culture, transfection, TUNEL assay, immunostaining and fluorescence microscopy

Fibril formation, thioflavin T binding, electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy

To determine the time course of ThT binding of fibrils formed with synthetic TDP-43 peptide, the wild-type or A315T mutant TDP-43 peptide or the control peptide was incubated at 250 μM in PBS (pH 7.0) with ThT. Dynamic changes in ThT binding at 37 °C with time were detected as fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units (AU). EM images of fibrils formed with the wild-type or A315T TDP-43 synthetic peptides were taken after incubation at 1.25 mM in PBS (pH 7.0) at 37 °C for 10 d with rotation at 240 r.p.m.

Time-lapse AFM images of the wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43 synthetic peptide were taken during the formation of protofibrils and fibrils after incubation of peptides in aqueous solution at a concentration of 20 mM for 0, 7 h, 13 h and 17 h. All the images were obtained on a mica surface. The corresponding cross-sectional profiles for the wild-type and A315T mutant TDP-43 peptides were measured to determine the thickness of the fibrils with z scale bars included for the AFM images.

Details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Baralle, E. Buratti, B. Cui, D. Kuo, N. Jayaram, Y. Li, M. Mishra, S. Perrett, M.-Y. Shen, M.-J. Zhang and T. Siddique for providing invaluable suggestions and reagents and for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank members of the Wu laboratory for stimulating discussions and suggestions. We thank L. Guo and L. Wang for technical assistance and A. Joselin for help in the early stage of the work. W.G. (grant 2009CB825402) and Y.C., H.Y. and Q.X. (grant 2010CB529603) are supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) China 973 Project. J.Y.W. is supported by funds from Northwestern University and the Chinese Academy of Science (CAS). Y.Y. and C.W. are supported by CAS and MOST. We also thank the US National Institutes of Health (grant AG13854 to M.M. and E.H.B.) for support.

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available on the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology website.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.Y.W., W.G., X.Z., K.F. and E.J.R. designed the study; W.G., Y.C., X.Z., A.K., P.R., X.C., E.J.R., M.Y., L.Z., J.L., M.X., Y.Y., C.W., D.Z., K.F., E.J.R. and J.Y.W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; H.Y., L.Z., J.L., Y.S., K.F., Q.X. and J.Y.W. supervised the experiments and discussed and analyzed the data; E.H.B. and M.M. provided crucial tissue samples and revised the manuscript; W.G., E.J.R. and J.Y.W. wrote the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Harvey RJ, Skelton-Robinson M, Rossor MN. The prevalence and causes of dementia in people under the age of 65 years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1206–1209. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackenzie IR, et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0612-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arai T, et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann M, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, et al. Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2009;323:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neumann M, et al. A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Brain. 2009;132:2922–2931. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann M, Kwong LK, Sampathu DM, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. TDP-43 proteinopathy in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: protein misfolding diseases without amyloidosis. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1388–1394. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.10.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Multiple roles of TDP-43 in gene expression, splicing regulation, and human disease. Front Biosci. 2008;13:867–878. doi: 10.2741/2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. TDP-43 and FUS/TLS: emerging roles in RNA processing and neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R46–R64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang HY, Wang IF, Bose J, Shen CK. Structural diversity and functional implications of the eukaryotic TDP gene family. Genomics. 2004;83:130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasegawa M, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:60–70. doi: 10.1002/ana.21425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Igaz LM, et al. Expression of TDP-43 C-terminal fragments in vitro recapitulates pathological features of TDP-43 proteinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8516–8524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809462200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igaz LM, et al. Enrichment of C-terminal fragments in TAR DNA-binding protein-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in brain but not in spinal cord of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:182–194. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreedharan J, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319:1668–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegorzewska I, Bell S, Cairns NJ, Miller TM, Baloh RH. TDP-43 mutant transgenic mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18809–18814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908767106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wils H, et al. TDP-43 transgenic mice develop spastic paralysis and neuronal inclusions characteristic of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3858–3863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912417107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu YF, et al. Wild-type human TDP-43 expression causes TDP-43 phosphorylation, mitochondrial aggregation, motor deficits, and early mortality in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10851–10859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1630-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou H, et al. Transgenic rat model of neurodegeneration caused by mutation in the TDP gene. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barmada SJ, et al. Cytoplasmic mislocalization of TDP-43 is toxic to neurons and enhanced by a mutation associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:639–649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, et al. A Drosophila model for TDP-43 proteinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3169–3174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913602107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagriantsev SN, Kushnirov VV, Liebman SW. Analysis of amyloid aggregates using agarose gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 2006;412:33–48. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prospéri MT, Ferbus D, Karczinski I, Goubin G. A human cDNA corresponding to a gene overexpressed during cell proliferation encodes a product sharing homology with amoebic and bacterial proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11050–11056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y, et al. Presenilin-1 protects against neuronal apoptosis caused by its interacting protein PAG. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:126–138. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasteiger E, et al. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3784–3788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhaskaran R, Ponnuswamy PK. Dynamics of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1984;24:180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1984.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deléage G, Roux B. An algorithm for protein secondary structure prediction based on class prediction. Protein Eng. 1987;1:289–294. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.4.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris AL, MacArthur MW, Hutchinson EG, Thornton JM. Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates. Proteins. 1992;12:345–364. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen L, et al. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6036–6046. doi: 10.1021/bi002555c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu L, Zhang XJ, Wang LY, Zhou JM, Perrett S. Relationship between stability of folding intermediates and amyloid formation for the yeast prion Ure2p: a quantitative analysis of the effects of pH and buffer system. J Mol Biol. 2003;328:235–254. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng JS, et al. Collagen VI protects neurons against Aβ toxicity. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:119–121. doi: 10.1038/nn.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorenzo A, Yankner BA. Beta-amyloid neurotoxicity requires fibril formation and is inhibited by congo red. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12243–12247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forloni G, et al. Neurotoxicity of a prion protein fragment. Nature. 1993;362:543–546. doi: 10.1038/362543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cushman M, Johnson BS, King OD, Gitler AD, Shorter J. Prion-like disorders: blurring the divide between transmissibility and infectivity. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1191–1201. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson BS, McCaffery JM, Lindquist S, Gitler AD. A yeast TDP-43 proteinopathy model: exploring the molecular determinants of TDP-43 aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6439–6444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nonaka T, Kametani F, Arai T, Akiyama H, Hasegawa M. Truncation and pathogenic mutations facilitate the formation of intracellular aggregates of TDP-43. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3353–3364. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang YJ, et al. Aberrant cleavage of TDP-43 enhances aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7607–7612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900688106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson BS, et al. TDP-43 is intrinsically aggregation-prone, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutations accelerate aggregation and increase toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20329–20339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corrado L, et al. High frequency of TARDBP gene mutations in Italian patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:688–694. doi: 10.1002/humu.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kametani F, et al. Identification of casein kinase-1 phosphorylation sites on TDP-43. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382:405–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36337–36343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feiguin F, et al. Depletion of TDP-43 affects Drosophila motoneurons terminal synapsis and locomotive behavior. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1586–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu Y, Ferris J, Gao FB. Frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated disease protein TDP-43 promotes dendritic branching. Mol Brain. 2009;2:30. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-2-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraemer BC, et al. Loss of murine TDP-43 disrupts motor function and plays an essential role in embryogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:409–419. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gendron TF, Josephs KA, Petrucelli L. Transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43): mechanisms of neurodegeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2010;36:97–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sleegers K, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. Molecular pathways of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:71–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ash PE, et al. Neurotoxic effects of TDP-43 overexpression in C. elegans. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3206–3218. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bagriantsev S, Liebman SW. Specificity of prion assembly in vivo [PSI+] and [PIN+] form separate structures in yeast. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51042–51048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao X, et al. Progranulin promotes neurite outgrowth and neuronal differentiation by regulating GSK-3β. Protein Cell. 2010;1:552–562. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuasa-Kawada J, Kinoshita-Kawada M, Wu G, Rao Y, Wu JY. Midline crossing and Slit responsiveness of commissural axons require USP33. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1087–1089. doi: 10.1038/nn.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.