Abstract

One of the recent advances in the epigenetic field is the demonstration that the Tet family of proteins are capable of catalyzing conversion of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) of DNA to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC). Interestingly, recent studies have shown that 5hmC can be further oxidized by Tet proteins to generate 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC), which can be removed by thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG). To determine whether Tet-catalyzed conversion of 5mC to 5fC and 5caC occurs in vivo in zygotes, we generated antibodies specific for 5fC and 5caC. By immunostaining, we demonstrate that loss of 5mC in the paternal pronucleus is concurrent with the appearance of 5fC and 5caC, similar to that of 5hmC. Importantly, instead of being quickly removed through an enzyme-catalyzed process, both 5fC and 5caC exhibit replication-dependent dilution during mouse preimplantation development. These results not only demonstrate the conversion of 5mC to 5fC and 5caC in zygotes, but also indicate that both 5fC and 5caC are relatively stable and may be functional during preimplantation development. Together with previous studies, our study suggests that Tet-catalyzed conversion of 5mC to 5hmC/5fC/5caC followed by replication-dependent dilution accounts for paternal DNA demethylation during preimplantation development.

Keywords: 5fC, 5caC, preimplantation, demethylation

Introduction

As one of the best-studied epigenetic modifications, DNA methylation has been linked to many biological processes including regulation of gene expression, suppression of transposable elements, genomic imprinting, and X chromosome inactivation 1, 2, 3. Although enzymes that catalyze DNA methylation have been well-characterized 4, how DNA methylation is removed is just beginning to be revealed 5.

Global loss of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) was first reported in zygotes where the paternal genome is preferentially demethylated 6, 7. A similar observation was also reported in the primordial germ cells (PGCs) during the establishment of gender-specific DNA methylation patterns 8. Despite great efforts in identifying the responsible enzymes, the identity of the putative DNA demethylase(s) has remained elusive 5, 9. Recent discovery that 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) is an integral component of genomic DNA of certain mammalian cell types 10, 11 and the demonstration that the Tet family proteins are capable of converting 5mC of DNA to 5hmC 11, 12 have raised the possibility that Tet proteins may be involved in the DNA demethylation process. Indeed, immunostaining of the zygotes at different pronuclear stages have shown that loss of 5mC in the male pronucleus correlates with the appearance of 5hmC 13, 14, 15, 16. Importantly, siRNA-mediated knockdown or targeted deletion of Tet3 greatly reduced or completely abolished the conversion of 5mC to 5hmC which supports the notion that Tet3 is responsible for the conversion of 5mC to 5hmC in the zygotes 13, 16. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrates that instead of being actively removed, 5hmC generated in the zygotes is passively diluted in a replication-dependent manner during preimplantation development 14.

In addition to generating 5hmC, two recent studies have demonstrated that Tet proteins are capable of iterative oxidation of 5mC to 5fC and 5caC 17, 18. Interestingly, while Ito et al. find that 5fC is readily detectable, He et al. report that 5hmC is efficiently converted to 5caC with no detectable 5fC. The demonstration that 5fC accumulates in vivo 18, 19 at a higher level than 5caC 18 in many tissues and cell types suggests that the generation of 5fC and 5caC and their further processing by TDG 17, 20 are subject to regulation. To study the generation and fate of 5fC and 5caC in vivo, we generated antibodies against these newly discovered cytosine derivatives. Here we demonstrate that appearance of 5fC and 5caC in the male pronucleus is concomitant with loss of 5mC in zygotes and that both 5fC and 5caC are gradually diluted in a replication-dependent manner during preimplantation development.

Results and Discussion

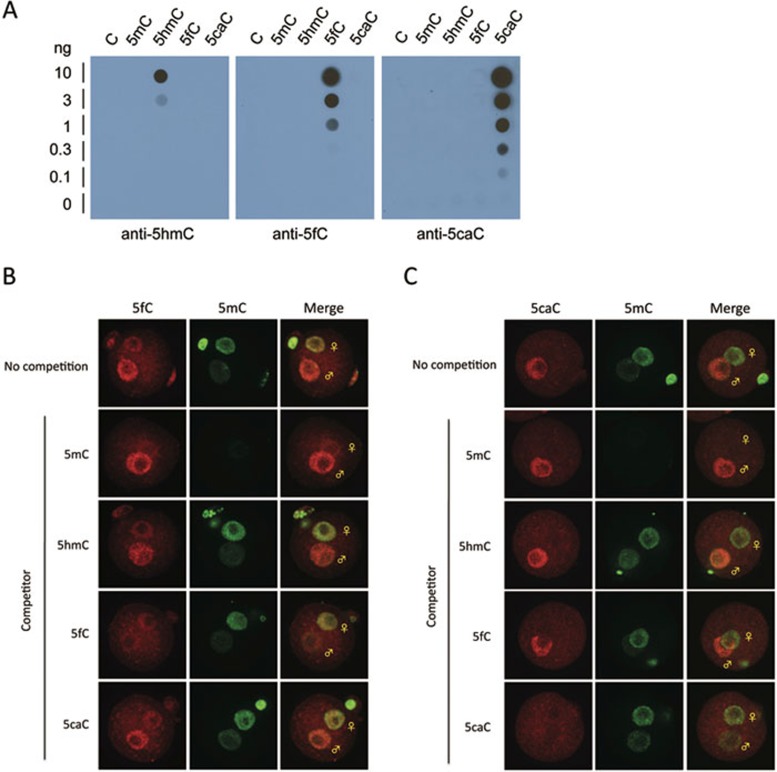

Generation and characterization of antibodies specific for 5fC and 5caC

To study the in vivo dynamics and to understand their function, we developed rabbit polyclonal antibodies against 5fC and 5caC, respectively. Dot blot analysis demonstrates that both antibodies are highly specific with no obvious cross-reactivity for other cytosine modifications (Figure 1A). To explore their utility in immunostaining, we co-stained 5mC with 5fC or 5caC using pronucleus stage 4-5 mouse zygotes and found that both 5fC and 5caC signals are enriched in the male pronucleus relative to female pronucleus (Figure 1B and 1C, top panels). To test for antibody specificity, we performed competition assays, which demonstrate that the 5fC signal can only be competed by 5fC nucleoside, while the 5caC signal can only be competed by 5caC nucleoside. These results demonstrate that both antibodies are specific with little reactivity to other modified cytosine residues.

Figure 1.

Characterization of 5fC and 5caC antibody specificity. (A) The 5fC and 5caC antibodies recognize 5fC and 5caC-containing oligo DNA in dot-blot assays. Different amounts of 38-mer DNA oligos where C are either C, 5mC, 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC were spotted on membrane and were probed with 5hmC (Active Motif), 5fC, and 5caC antibodies, respectively. (B, C) Representative confocal microscopy images of zygotes co-stained with 5mC and 5fC (B) or 5caC (C) antibodies in the absence or presence of 2 μM of competitive nucleosides indicated.

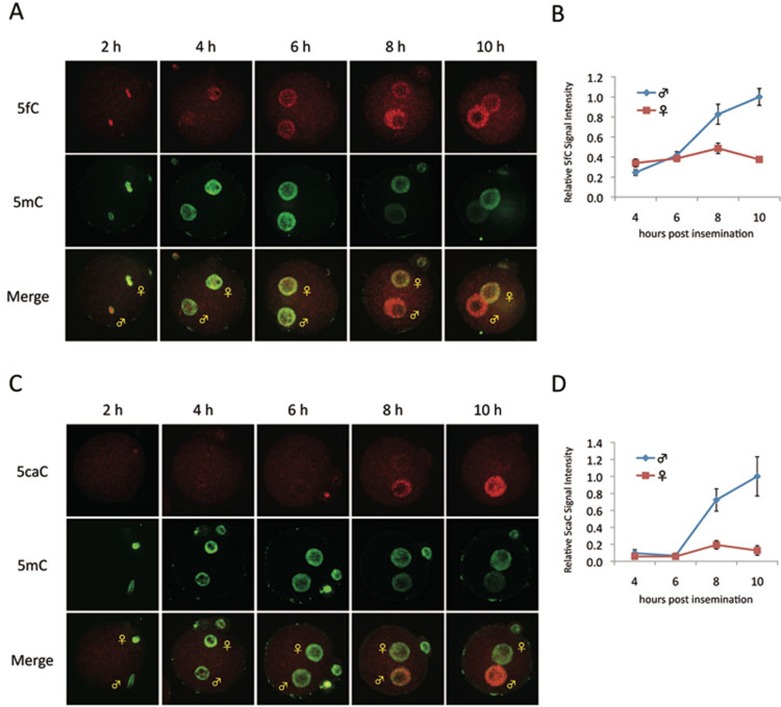

Increase of 5fC and 5caC levels in the male pronucleus correlates with the decrease of 5mC level in zygotes

Having demonstrated the specificity of the 5fC and 5caC antibodies, we next analyzed the dynamics of 5fC and 5caC during pronuclear development in zygotes by immunostaining. While the intensities of 5fC signals in the male and female pronuclei are low until 6 h after fertilization, the signal in the male pronucleus is significantly increased relative to the female pronucleus 8 h after insemination (Figure 2A, 2B). Interestingly, the dynamics of 5fC increase correlate with the decrease of 5mC in the male pronucleus (Figure 2A, 2B). Similar staining using the 5caC antibody demonstrates that 5caC signal is barely detected in both male and female genome until 6 h after fertilization, and then preferentially appears in the male pronucleus concurrent with decrease of 5mC in the male pronucleus after 8 h post insemination (Figure 2C, 2D). These results suggest that loss of 5mC in the male pronucleus is concurrent with the appearance of 5fC and 5caC. Together with previous findings that loss of 5mC is concurrent with the appearance of 5hmC 13, 14, 15, 16, and that Tet proteins are capable of iterative oxidation of 5mC to generate 5fC and 5caC 17, 18, the above results suggest that 5mC in the male pronucleus is converted to all three oxidation forms (5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC). In addition, these results also demonstrate that ES cell is not the only cell type where 5caC is detectable.

Figure 2.

Loss of 5mC staining in the paternal pronucleus correlates with increase in 5fC and 5caC staining in zygotes. (A, C) Representative confocal microscopy images of mouse zygotes co-stained with 5mC (green), 5fC (A) or 5caC (C) (red) at different times post-insemination. The intensity of 5mC and 5fC is similar in male and female pronuclei until 6 h post-insemination (hpi). Concomitant with the decrease in the 5mC intensity in male pronuclei, the intensity of 5fC increases between 8-10 hpi (A). In terms of 5caC, very little is detected before 6 hpi. Its accumulation in the male pronucleus correlates with the decrease of 5mC (C). (B, D) Quantification of the relative levels of 5fC (B) and 5caC (D) in male and female pronuclei at different times post-insemination. The signal intensity is quantified using AxioVision software. The signal intensity in the paternal pronucleus at 10 hpi is set as 1.0. The experiments were repeated for three times and 15-25 zygotes were quantified for each stage. Bars represent standard errors.

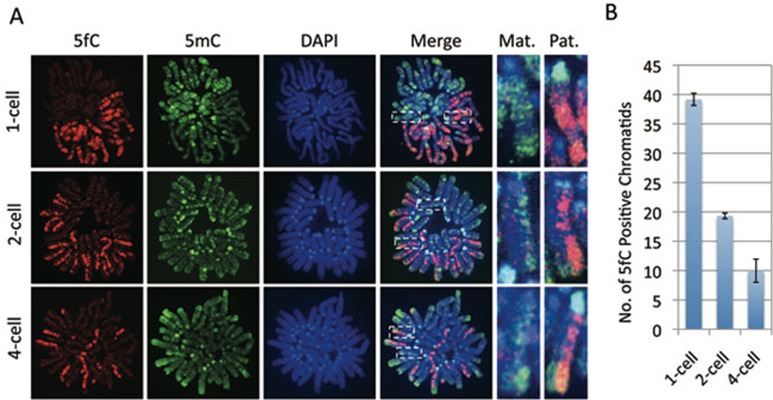

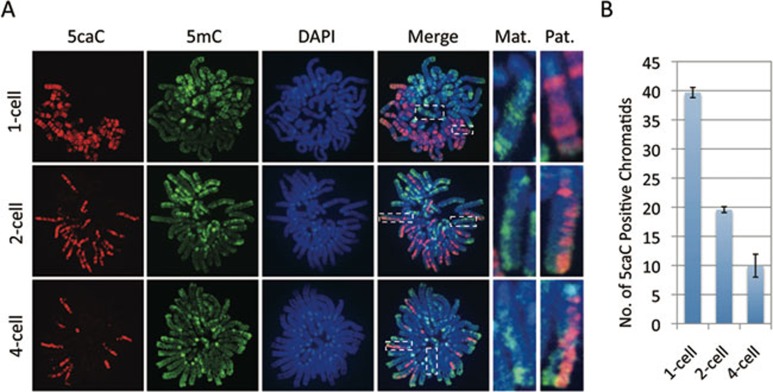

Replication-dependent dilution of 5fC and 5caC during preimplantation development

After demonstrating that 5mC in the male pronucleus is converted to 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC in zygotes, we attempted to investigate their fate during preimplantation development. We have recently shown that 5hmC is gradually diluted in a replication-dependent manner during preimplantation development 14. Given that 5fC and 5caC, but not 5hmC, can be efficiently processed by TDG 17, 20, we were curious whether 5fC and 5caC generated in zygotes are quickly processed by TDG or TDG-like enzymes. Alternatively, they may be relatively stable and are lost by replication-dependent dilution similar to that of 5hmC. To differentiate between these two possibilities, we prepared mitotic chromosome spreads of embryos at 1-cell, 2-cell, and 4-cell stages. Co-staining of the chromosome spreads with antibodies against 5mC together with 5fC or 5caC revealed that, at the 1-cell stage, the sperm and oocyte-derived chromosomes are compartmentalized with 5fC (Figure 3A) and 5caC (Figure 4A) specifically enriched in the sperm-derived chromosomes while 5mC are specifically enriched in the egg-derived chromosomes (Figures 3A and 4A). Interestingly, similar staining of mitotic chromosomes at the two-cell stage revealed that only one of the two sister chromatids is enriched for 5fC (Figure 3A) or 5caC (Figure 4A) indicating that the 5fC and 5caC level of each blastomere is reduced to half in each round of DNA replication. Despite the lack of 5fC/5caC staining in the chromosomes of egg origin, their 5mC signal in one of the two sister chromatids is significantly reduced to a level comparable to that of sperm origin (Figures 3A and 4A), consistent with the notion that the methylation level of maternal DNA is subjected to a replication-dependent dilution 21. Further analysis of the 5fC and 5caC staining of 4-cell stage embryo blastomeres revealed that the chromosomes containing 5fC and 5caC are gradually reduced (Figures 3A and 4A). Quantification of the 5fC and 5caC positive chromatids indicates that they are going through a replication-dependent dilution process (Figures 3B and 4B). Collectively, the above results suggest that both 5fC and 5caC generated in zygotes are passively diluted, rather than actively removed, through replication, similar to that of 5hmC 14.

Figure 3.

Replication-dependent loss of 5fC during mouse preimplantation development. (A) Representative images of mitotic chromosome spreads co-stained with 5fC (red), 5mC (green) antibodies or DAPI (blue) at 1-cell, 2-cell, and 4-cell stages as indicated. Shown are the images of chromosomes from one blastomere at each developmental stage. Note that 5fC is present in both chromatids of the sperm-derived chromosomes at 1-cell stage embryos. However, only one of the two chromatids of the sperm-derived chromosomes stained positively for 5fC at the 2-cell stage, and only about a quarter of the sister chromatids stained positively for 5fC at the 4-cell stage. The dotted squares represent the enlarged paternal (Pat.) or maternal (Mat.) chromosomes, respectively. (B) Quantification of the total numbers of 5fC positive chromatids in each blastomere. When partial regions of the chromatids were positively stained due to sister chromatid exchange, the total length of 5fC-enriched chromatid segments in each blastomere was determined and calculated in terms of the number of chromosome equivalent. The experiments were repeated for four times and the total number of blastomeres examined at the 1-cell, 2-cell, and 4-cell stages were 12, 22, and 19, respectively. Bars represent standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Replication-dependent loss of 5caC during mouse preimplantation development. (A) Representative images of mitotic chromosome spreads co-stained with 5caC (red), 5mC (green) antibodies or DAPI (blue) at 1-cell, 2-cell, and 4-cell stages as indicated. Shown are the images of chromosomes from one blastomere at each developmental stage. Note that 5caC is present in both chromatids of the sperm-derived chromosomes at 1-cell stage embryos. However, only one of the two chromatids of the sperm-derived chromosomes stained positively for 5caC at the 2-cell stage, and only about a quarter of the sister chromatids stained positively for 5caC at the 4-cell stage. The dotted squares represent the enlarged paternal (Pat.) or maternal (Mat.) chromosomes, respectively. (B) Quantification of the total numbers of 5caC positive chromatids in each blastomere. The quantification method is the same as that described in Figure 3B. The experiments were repeated for four times and the total number of blastomeres examined at the 1-cell, 2-cell, and 4-cell stages were 19, 24, and 27, respectively. Bars represent standard deviation.

Recent studies have demonstrated that 5mC in male pronucleus is converted to 5hmC 13, 14, 15, 16. Given that bisulfite sequencing does not differentiate between 5hmC and 5mC 22, 23, a reasonable way to explain why some regions, such as Line and other repeat sequences 24, 25, are subjected to active demethylation as assayed by bisulfite sequencing is that the 5mC in those sequences are further converted to C or a state that bisulfite sequencing would recognize as C. Our demonstration that 5mC is indeed converted not only to 5hmC, but also to 5fC and 5caC in zygotes, in combination with the fact that the 5caC base is recognized as an 'unmethylated' cytosine in bisulfite sequencing 17 suggests that 5mC in Line and other repeat sequences may not be “fully” demethylated in zygotes. Given that different oxidation forms of 5mC might have different functions, how the processivity of Tet proteins is regulated is of great importance.

We demonstrate that 5mC in the male pronucleus is converted to 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC in zygotes. At a global level, these cytosine derivatives are unlikely to be quickly removed by an enzymatic process. Instead, they are gradually diluted in a replication-dependent manner. It is currently unclear why the paternal genome undergoes this Tet3-mediated 5mC to 5hmC/5fC/5caC conversion process 13, rather than directly going through a replication-dependent dilution on 5mC which takes place in the egg-derived genome 21. Given that deficiency in Tet3 impedes paternal Oct4 and Nanog gene demethylation and oocytes lacking Tet3 have a reduced capacity in reprogramming injected somatic cell nuclei 13, the generation and subsequent dilution of the 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC marks might be important for preimplantation development and germ cell reprogramming. Future work should reveal how these new cytosine derivatives contribute to these processes.

Materials and Methods

5fC and 5caC antibody generation and characterization

To generate 5fC and 5caC antibodies, ribonucleoside forms of 5fC and 5caC were conjugated to KLH before being injected into rabbits. For dot blot characterization of the anti-sera specificity, different amounts of 38-mer DNA oligos with the following sequences, 5′-Biotin-AGCCXGXGCXGXGCXGGTXGAGXGGCXGCTCCXGCAGC-3′, where X is either a C or modified C, were denatured with 0.1 M NaOH and spotted on nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad, 162-0112). The membrane was baked at 80 °C and then blocked in 5% non-fat milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with 1:10 000 dilution of anti-5hmC antiserum (Active Motif, catalog #39769), 1:5 000 dilution of anti-5fC antiserum or 1:2 000 dilution of anti-5caC antiserum overnight at 4 °C, respectively. After three rounds of washes with TBST, membranes were incubated with 1:2 000 dilution of HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. The membranes were then washed with TBST and treated with ECL. For competition in immunostaining, 5mC, 5hmC (Zymo Research, D1035, D1045) nucleotides, or 5fC and 5caC nucleosides (Berry & Associates, PY7589 and PY7593) were added to the primary antibody with a final concentration of 2 μM and preincubated for 1 h at 4 °C before staining.

Collection, culture, and whole mount immunostaining of preimplantation embryos

All animal studies were performed in accordance with guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The collection, culture, and immunostaining of preimplantation embryos were performed essentially as described previously 14. The primary antibody dilution factors are: anti-5mC (1:200, BI-MECY-0500, Eurogentec), anti-5fC (1:4 000), and anti-5caC (1:2 000).

Mitotic chromosome spread and immunocytochemistry

Preparation of mitotic chromosomes at 1-cell, 2-cell, and 4-cell stages was performed as previously described 14. The anti-5mC, anti-5fC, and anti-5caC antibodies are used with the dilution of 1:500, 1:2 000, and 1:2 000, respectively. Fluorescence detection, image acquisition and analysis were also performed as previously described 14.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Keck Oligo Synthesis Lab of Yale University for oligo synthesis and Susan Wu (Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated) for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by HHMI and NIH (U01DK089565). YZ is an Investigator of the HHMI.

References

- Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:295–304. doi: 10.1038/nrg2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Matsui Y. Epigenetic events in mammalian germ-cell development: reprogramming and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:129–140. doi: 10.1038/nrg2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll MG, Bestor TH. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SC, Zhang Y. Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:607–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer W, Niveleau A, Walter J, Fundele R, Haaf T. Demethylation of the zygotic paternal genome. Nature. 2000;403:501–502. doi: 10.1038/35000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald J, Engemann S, Lane N, et al. Active demethylation of the paternal genome in the mouse zygote. Curr Biol. 2000;10:475–478. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajkova P, Erhardt S, Lane N, et al. Epigenetic reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Mech Dev. 2002;117:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi SK, Bestor TH. The colorful history of active DNA demethylation. Cell. 2008;133:1145–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, D'Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu TP, Guo F, Yang H, et al. The role of Tet3 DNA dioxygenase in epigenetic reprogramming by oocytes. Nature. 2011;477:606–610. doi: 10.1038/nature10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Zhang Y. Replication-dependent loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mouse preimplantation embryos. Science. 2011;334:194. doi: 10.1126/science.1212483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K, Jin SG, Pfeifer GP, Szabo PE. Reprogramming of the paternal genome upon fertilization involves genome-wide oxidation of 5-methylcytosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3642–3647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wossidlo M, Nakamura T, Lepikhov K, et al. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian zygote is linked with epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2011;2:241. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffeneder T, Hackner B, Truss M, et al. The discovery of 5-formylcytosine in embryonic stem cell DNA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:7008–7012. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti A, Drohat AC. Thymine DNA glycosylase can rapidly excise 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine: POTENTIAL IMPLICATIONS FOR ACTIVE DEMETHYLATION OF CpG SITES. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35334–35338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.284620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougier N, Bourc'his D, Gomes DM, et al. Chromosome methylation patterns during mammalian preimplantation development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2108–2113. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pastor WA, Shen Y, Tahiliani M, Liu DR, Rao A. The behaviour of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in bisulfite sequencing. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SG, Kadam S, Pfeifer GP. Examination of the specificity of DNA methylation profiling techniques towards 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Kang YK, Koo DB, et al. Differential DNA methylation reprogramming of various repetitive sequences in mouse preimplantation embryos. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N, Dean W, Erhardt S, et al. Resistance of IAPs to methylation reprogramming may provide a mechanism for epigenetic inheritance in the mouse. Genesis. 2003;35:88–93. doi: 10.1002/gene.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]